Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Progression For Teaching The Overhead Lifts.10

Enviado por

brownsj1983Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Progression For Teaching The Overhead Lifts.10

Enviado por

brownsj1983Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

National Strength & Conditioning Association

Volume 25, Number 4, pages 4449

A Progression for Teaching the

Overhead Lifts

Greg Frounfelter, DPT, ATC, CSCS

Agnesian Healthcare

Fond du Lac, Wisconsin

Keywords: overhead lifting; exercise instruction; exercise

progression; teaching.

BASIC STRENGTH AND CONDItioning programs emphasize

multi-jointed exercises that exercise a relatively large amount of

muscle mass. This is true regardless of what part of the body is

being trained. In terms of training

the upper body, the bench press

or one of its variations, such as

the incline press, dumbbell press,

or decline press, is often used.

However the bench press is not

the only core lift that can be used

to develop upper body strength.

Overhead lifts are sometimes underutilized as core exercises to develop upper body strength and

overall explosiveness at the high

school level of athletics. The overhead lifts discussed for the purpose of this article will be the overhead (military) press, the push

press, and the split jerk.

The purpose of this article is

to present a progression for instructing young athletes how to

perform the overhead lifts. Many

high school strength and conditioning programs can benefit

from such a teaching progression

in that high school weight training instructors may be able to

more safely and effectively teach

students the proper methods of

overhead lifting.

44

Strength and Conditioning Journal

Safety Considerations

Special considerations must be

made when using overhead lifts.

Lifting an object overhead requires

balance of the objects center of

gravity (CG) over the CG of the

lifter. In addition to proper alignment, both CGs must be within

the base of support of the lifter in

order to provide balance and stability (4, 5). This is an important

safety factor to consider when

coaching the overhead lifts. For

these reasons, it is important to

coach athletes not to walk around

while they are still holding the bar

overhead. Allowing this might

cause the lifter to lose control of the

bar and injury could result. The

lifter is only stable and balanced

when all CGs are aligned and within the lifters base of support.

Overhead lifts where the bar is

placed behind the neck may be

potentially dangerous to the

shoulder complex (2). Reasoning

for this is the position of the

shoulder complex during the exercise. At some point during the

concentric and eccentric phases of

a lift done from behind the neck,

the glenohumeral joint is placed in

near maximum external rotation,

abduction, and extension with an

external load (2). In this position,

it only takes a minor loss of balance with the barbell to result in a

major injury such as an anteriorinferior subluxation or dislocation

of the shoulder (6). Keeping the

bar at the front of the neck is safer

because it prevents this potentially dangerous positioning, and the

muscle groups worked do not

seem to vary significantly (2).

Another important coaching

point is to tell the athletes not to

hold their breath while lifting.

Have them breathe out as they

push overhead and breath in

when the bar is being lowered. In

this manner, a Valsalva maneuver

can be avoided and the risk of an

athlete fainting while lifting can

be reduced.

Encourage the use of spotters

at all times. Although it is inherently difficult to spot some of the

overhead lifts, spotters help to remind those who are close by to

stay out of the way of the lift and

that the lift itself is serious business. If an athlete needs to dump

August 2003

Figure 1.

Military press/overhead lifts starting position.

an overhead lift, especially one

performed ballistically, he or she

should try to push away from the

weight and let the weight drop. In

this manner the athlete can ensure not getting hit by the barbell

and the weight will most likely

land on the lifters platform and

not on someone else in the training facility.

Power racks allow the athletes

to take the bar at shoulder height.

This seems to reduce fatigue and

promote proper overhead lifting

technique. If you do not have access to such a rack, instruction in

proper cleaning technique may be

used to get the bar to a chest high

position to begin overhead work.

Do not allow athletes to sacrifice good technique for the sake of

using more weight. Prevent injuries by starting every athlete

with a light load; many athletes

initially start with an empty bar. If

an athlete cannot safely handle a

standard 45-pound bar, a lighter

bar (in the 1528-pound range)

can be used. With these lighter

loads, athletes can build confidence and strength in their technique so they can eventually handle the rigors of the standard bar.

Athletes who have a history of

shoulder injury generally perform

these exercises to within their tolerance. Supplemental shoulder

work may need to be utilized for

their specific needs.

Methodology of the

Progression

Figure 2.

Military Press

Have the athlete assume an upright stance with a very light barbell (preferably stripped down)

held in a modified racked position

(Figure 1). Then have the athlete

press the bar to arms length overhead and pause. The bar should

be held over the crown of the head

for a count of one (Figure 2). The

Overhead lifts completion.

August 2003

Strength and Conditioning Journal

45

bar is returned to the starting position emphasizing control. Make

sure the athlete does not lean

backward or hyperextend the low

back while performing this lift.

This exercise indirectly teaches

the athlete to keep his or her body

segments aligned and balance

maintained by having the athlete

bring the bar over the crown of the

head.

Push Press

Once the athlete is proficient at

the military press, he or she can

then progress to the push press.

The athlete should have developed

some sense of how to keep the bar

balanced overhead and should be

ready to move on to more ballistic

movements. The starting position

is the same as with the military

press. The start of the movement

involves the athlete bending both

knees and pushing upward with

them (Figure 3). After giving the

bar momentum with the legs, the

arms drive the bar overhead into

the finished position. This is again

held for a one-count and slowly returned to the starting position.

The push press is the same as a

military press where the lifter

cheats by using the legs.

Split Jerk

After the push press is mastered,

the athlete is ready to move on to

the split jerk (jerk). Footwork is an

important component of this exercise. In the jerk, the feet move into

a split position where one foot is in

front, one is in back, both legs are

bent at the knees, and both lower

extremities are moved slightly laterally from the starting position

(Figures 4 and 5).

Start the teaching process by

having the athlete stand with

hands on the hips. The feet are

about shoulder width apart (Figure 4). The athlete is then instructed to quickly move one foot

46

Figure 3.

Knee bending in preparation of the push press.

Figure 4.

Starting position for learning the jerk footwork.

Strength and Conditioning Journal

August 2003

forward and one foot backward

while keeping the heels the same

distance apart. The athlete should

land with both knees bent and the

toes of both feet pointing slightly

toward the midline of the body

(Figure 5). The front foot should be

flat on the ground. The back heel

should not be in contact with the

ground. The toes of the back foot

should be slightly pointed toward

the midline of the body and not

pointed out (Figure 6). By pointing

the toes in, excessive stress on the

back knee is reduced and balance

is aided (1).

A cross can be drawn on the

lifting surface to provide feedback

for the athlete in regard to foot

placement (3) (Figures 49). The

athlete should not perform the motion as to make the base of support

too narrow. This can make the

athlete look like he or she is trying

to walk a tight rope (Figure 7). This

is inherently unstable and the athlete should be encouraged to keep

the distance between the feet constant from start to finish during

the lift. Work on the lateral foot positioning by cueing the athlete to

shoot his or her feet towards their

respective front and back corners

of the platform; the correct motion

foot placement usually occurs

quite naturally with this technique. In final preparation for performing the jerk with a barbell, the

athlete assumes the same starting

position but initiates a small jump

before performing the proper footwork.

Once the athlete is proficient

with the footwork, it is time to perform the jerk with an empty barbell. The athlete stands in the same

starting position as with the push

press. However, as the athlete dips,

he or she is not preparing for a

slight leg push, but rather the legs

are preparing for a tremendous upward drive with the arms (Figure

8). As the athlete drives upward

August 2003

with the legs and arms, the bar

gains inertia and continues overhead. It is at this time that the athlete performs the split with the legs

as practiced and the arms are

thrust upward as they catch the

bar at arms length over the crown

of the head (Figure 9). Once the bar

is properly positioned, the athlete

straightens the front knee (Figure

10) and takes small steps alternately with both feet until he or she

is in the finished overhead position.

Taking these small steps will allow

the athlete to be able to maintain

segmental control and balance

Figure 5.

Finished position for learning the jerk footwork.

Figure 6.

Incorrect rear foot positioning (back toes are pointed out).

Strength and Conditioning Journal

47

during the completion of the lift.

Again, the barbell is held over the

crown of the head for a one count

and the athlete returns the bar to

the starting position. Although the

bars return doesnt need to be performed as slowly as with the military or push presses, it should be

done in a controlled manner to reduce the risk of injury. Getting the

bar up overhead is only half the

battle; the lift is not finished until

both feet are aligned with the barbell overhead.

Conclusion

The goal of any type of exercise

progression should be for progressive instruction and mastery of the

exercise as safely as possible. This

progression for training/teaching

the overhead lifts accomplishes

this by allowing the athlete to develop and master particular skills

before progressing to more complex lifts. Safety concerns are inherently incorporated in the progression secondary to light starting

loads and gradual load increases

as technique and strength improves. After trying this method,

you will find that your athletes

learn how to do overhead movements more quickly and safely.

This progression may require an

initial investment of time in instruction; however, the athletes

will learn proper lifting technique

first, and this technique will allow

them to safely gain strength and

power. This increase in upper body

strength and power will hopefully

allow them to perform at their optimum and perform well within all

their athletic endeavors.

Figure 7.

Incorrect foot placement (base of support too narrow).

Figure 8.

Start of the jerk (dip and drive).

References

1. Baker, G. The United States

Weightlifting Federation Coaching Manual, Volume 1: Technique. Colorado Springs, CO:

United States Weightlifting

Federation, 1989.

48

Strength and Conditioning Journal

August 2003

Figure 9.

Catching the bar during the jerk.

2. Durall,C.J., R.C. Manske, and

G.J. Davies. Avoiding shoulder

injury from resistance training. Strength Cond. J. 23(5):

1018. 2001.

3. Jones, L. Senior Coach Manual. Colorado Springs, CO:

United States Weightlifting

Federation, 1991.

4. Kreighbaum, E., and K.

Barthels. Biomechanics: A

Qualitative Approach for

Studying Human Movement

(3rd ed.). New York, NY:

Macmillian Publishing Co.,

1990.

5. Norkin, C.C., and P.K. Levangie. Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA:

F.A. Davis Co., 1992.

6. Roy, S., and R. Irvin. Sports

Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation. Engelwood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1983.

Frounfelter

Greg Frounfelter works as a

physical therapist and Certified

Athletic Trainer for Agnesian

Healthcare in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. He serves as vice president

of the WSCA and is an adjunct

anatomy and physiology instructor at Moraine Park Technical College in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin.

Figure 10. Recovering from the jerk by straightening the front knee first.

August 2003

Strength and Conditioning Journal

49

Você também pode gostar

- Weightlifting USAW Level 1 Sports PerformanceDocumento50 páginasWeightlifting USAW Level 1 Sports PerformanceChris Kasinski100% (2)

- Mechanics and Development of Single Leg Vertical JumpingDocumento27 páginasMechanics and Development of Single Leg Vertical Jumpinginstantoffense100% (7)

- Periodization - Nick WinkelmanDocumento54 páginasPeriodization - Nick Winkelmanbrownsj1983100% (6)

- Business Personal StatementDocumento2 páginasBusiness Personal StatementBojan Ivanović50% (2)

- Princeton Football SUMMER MANUAL 2014Documento58 páginasPrinceton Football SUMMER MANUAL 2014brownsj1983100% (7)

- Bemidji State Football Strength and Conditioning ManualDocumento82 páginasBemidji State Football Strength and Conditioning ManualSparty74100% (2)

- Chapter 21 - Pitched RoofingDocumento69 páginasChapter 21 - Pitched Roofingsharma SoniaAinda não há avaliações

- Hoss Olympic FinalDocumento18 páginasHoss Olympic Finalnathan.purvis24100% (1)

- Joe Defranco - Super Strength PDFDocumento27 páginasJoe Defranco - Super Strength PDFVague90% (10)

- WeightLifting CourseDocumento32 páginasWeightLifting CourseMisterdj AsgayaAinda não há avaliações

- SPARQTrianing 2adays WorkoutsDocumento21 páginasSPARQTrianing 2adays WorkoutsCourtney JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- How To Get The Splits in 8 Easy StepsDocumento7 páginasHow To Get The Splits in 8 Easy StepslakpatAinda não há avaliações

- Shaver - Sprint TrainingDocumento89 páginasShaver - Sprint Trainingpanthercoach54100% (5)

- Salisbury University Strength & Conditioning ManualDocumento97 páginasSalisbury University Strength & Conditioning Manualbrownsj1983100% (1)

- Teaching ResumeDocumento2 páginasTeaching Resumeapi-281819463Ainda não há avaliações

- Grade 3 ReadingDocumento58 páginasGrade 3 ReadingJad SalamehAinda não há avaliações

- The Front Squat and Its Variations: Keywords: Depth Force Flexibility Strength Thoracic KyphosisDocumento7 páginasThe Front Squat and Its Variations: Keywords: Depth Force Flexibility Strength Thoracic KyphosisRosaneLacerdaAinda não há avaliações

- NSCA Coach 1.2 BrownDocumento5 páginasNSCA Coach 1.2 BrownRoger AugeAinda não há avaliações

- A Teaching Progression For Squatting Exercises.7Documento9 páginasA Teaching Progression For Squatting Exercises.7Rhiannon CristinaAinda não há avaliações

- 24 Shoulder PDFDocumento3 páginas24 Shoulder PDFLouit LoïcAinda não há avaliações

- The Barbell Bench Pull: Do It RightDocumento4 páginasThe Barbell Bench Pull: Do It RightCésar Morales GarcíaAinda não há avaliações

- CFJ Takano Jerk PDFDocumento5 páginasCFJ Takano Jerk PDFjames_a_amosAinda não há avaliações

- Feature Article: How To Train The Core: Specific To Sports MovementsDocumento10 páginasFeature Article: How To Train The Core: Specific To Sports MovementsManuel FerreiraAinda não há avaliações

- Core Training Progression for AthletesDocumento7 páginasCore Training Progression for Athletessalva1310Ainda não há avaliações

- The Countermovement ShrugDocumento4 páginasThe Countermovement ShrugAnonymous OikQYkAinda não há avaliações

- WSBB Guide for Beginners - Squat-compressedDocumento14 páginasWSBB Guide for Beginners - Squat-compressedKatya KAinda não há avaliações

- Exercise Technique Manual For Resistance Training 3rd Edition Ebook PDF VersionDocumento62 páginasExercise Technique Manual For Resistance Training 3rd Edition Ebook PDF Versiondavid.leroy848100% (37)

- Corrective Power Clean Teaching TechniquesDocumento24 páginasCorrective Power Clean Teaching TechniquesTim Donahey100% (7)

- Core TrainingDocumento8 páginasCore TrainingMari PaoAinda não há avaliações

- CFJ Catch Takano 3Documento6 páginasCFJ Catch Takano 3Nuno LemosAinda não há avaliações

- Developing The Straddle-Sit Press To HandstandDocumento5 páginasDeveloping The Straddle-Sit Press To HandstandValentin Uzunov100% (2)

- Weightlifting Pull in Power DevelopmentDocumento6 páginasWeightlifting Pull in Power DevelopmentAnonymous SXjnglF6ESAinda não há avaliações

- Form and Safety in Plyometric TrainingDocumento5 páginasForm and Safety in Plyometric Trainingsalva1310Ainda não há avaliações

- Core Strength Manual PDFDocumento20 páginasCore Strength Manual PDFKenny Omoya Arias100% (1)

- How to Jump Higher in 4 Steps - Improve Your Vertical LeapDocumento10 páginasHow to Jump Higher in 4 Steps - Improve Your Vertical LeapArmadah GedonAinda não há avaliações

- WSBB Guide for Beginners - Bench-compressedDocumento15 páginasWSBB Guide for Beginners - Bench-compressedKatya KAinda não há avaliações

- Jump Training SecretsDocumento3 páginasJump Training Secretsinfo7614Ainda não há avaliações

- 6 Power Cleans 17-4-2010Documento3 páginas6 Power Cleans 17-4-2010Khizar HayatAinda não há avaliações

- How To Power Clean Techniques Benefits VariationsDocumento25 páginasHow To Power Clean Techniques Benefits Variationsapi-547830869Ainda não há avaliações

- Specific Exercises For Discus Throwers: by V. Pensikov and E. DenissovaDocumento9 páginasSpecific Exercises For Discus Throwers: by V. Pensikov and E. Denissovalucio_jolly_roger100% (1)

- Improve Strength, Power and Reaction TimeDocumento1 páginaImprove Strength, Power and Reaction TimeLeRoy13Ainda não há avaliações

- Core Strength ManualDocumento20 páginasCore Strength Manualdnyanesh_23patilAinda não há avaliações

- Therapeutic Exercise ModuleDocumento26 páginasTherapeutic Exercise ModuleMar Jersey MartinAinda não há avaliações

- Strength and Conditioning For Triathletes: Bruce Day, BSC and Don Johnson, MD, Frcs CDocumento6 páginasStrength and Conditioning For Triathletes: Bruce Day, BSC and Don Johnson, MD, Frcs CeducobainAinda não há avaliações

- CHAPTER ONE ApparatesDocumento35 páginasCHAPTER ONE Apparatesዳን ኤልAinda não há avaliações

- Strengthen Rotator Cuffs with Cuban PressDocumento2 páginasStrengthen Rotator Cuffs with Cuban PressSlevin_KAinda não há avaliações

- Powerlifting PaperDocumento10 páginasPowerlifting PaperAng Yi XiuAinda não há avaliações

- Accessory Onslaught #1: The Squat: Primary Muscles UsedDocumento12 páginasAccessory Onslaught #1: The Squat: Primary Muscles Usedkarzinom100% (1)

- Functional Training for Athletes at All Levels: Workouts for Agility, Speed and PowerNo EverandFunctional Training for Athletes at All Levels: Workouts for Agility, Speed and PowerNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- Training Around InjuriesDocumento14 páginasTraining Around InjuriesPaulo André Prada de CamargoAinda não há avaliações

- 3-Part Trunk Strengthening RoutineDocumento5 páginas3-Part Trunk Strengthening RoutineAfizie100% (1)

- NSCA - Functional Training For SwimmingDocumento7 páginasNSCA - Functional Training For SwimmingLuiz Felipe100% (1)

- Strength Training For The Shoulder: Should Throwing Athletes Lift Weights Overhead?Documento7 páginasStrength Training For The Shoulder: Should Throwing Athletes Lift Weights Overhead?Oscar NgAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Exercise For Shoulder HealthDocumento5 páginas6 Exercise For Shoulder Healthsundar prabhuAinda não há avaliações

- Shoulder Injuries ReportDocumento9 páginasShoulder Injuries Reportley343100% (1)

- Glute HamDeveloperSit UpDocumento8 páginasGlute HamDeveloperSit UpMarco PMTAinda não há avaliações

- Ahoulder Performance For The Fitness AthleteDocumento9 páginasAhoulder Performance For The Fitness Athletefederico BiettiAinda não há avaliações

- How To Improve Your Vertical LeapDocumento12 páginasHow To Improve Your Vertical Leapskilzace100% (1)

- What Physios Should Know About Strength ConditioningDocumento5 páginasWhat Physios Should Know About Strength ConditioningfthugovsAinda não há avaliações

- Proper and Improper Execution of ExerciseDocumento24 páginasProper and Improper Execution of ExerciseFloieh QuindaraAinda não há avaliações

- Triple JumpDocumento4 páginasTriple Jumpapi-313469173Ainda não há avaliações

- Core Flexibility-Static and Dynamic Stretches For The CoreDocumento3 páginasCore Flexibility-Static and Dynamic Stretches For The CoreMagno FilhoAinda não há avaliações

- Youth Football Speed ProgramDocumento46 páginasYouth Football Speed Programdnutter01257675% (4)

- Weightlifting in Training For Athletics - Part 1: by Martin Zawieja-Koch AuthorDocumento18 páginasWeightlifting in Training For Athletics - Part 1: by Martin Zawieja-Koch AuthortaingsAinda não há avaliações

- Therapeutic Exercise Theory and PracticeDocumento155 páginasTherapeutic Exercise Theory and PracticeAbdulrhman MohamedAinda não há avaliações

- Tripple Jump Program TrainingDocumento5 páginasTripple Jump Program TrainingRezan RamliAinda não há avaliações

- Simplified Strength Training using your Bodyweight and a Towel at Home Vol. 1: Legs/Quads: VolNo EverandSimplified Strength Training using your Bodyweight and a Towel at Home Vol. 1: Legs/Quads: VolAinda não há avaliações

- Core Strength Key to Stable Body FlightDocumento18 páginasCore Strength Key to Stable Body FlightCornelius IntVeldAinda não há avaliações

- Regression Models of Sprint Vertical JumDocumento32 páginasRegression Models of Sprint Vertical Jumbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- 7 Habits of Program DesignDocumento6 páginas7 Habits of Program Designbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Physical Fitness and Performance Power VDocumento8 páginasPhysical Fitness and Performance Power Vbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Post-Activation Potentiation - Factors Affecting It and The Effect On PerformanceDocumento7 páginasPost-Activation Potentiation - Factors Affecting It and The Effect On PerformancedanialeduAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Acute Effects Between BackDocumento10 páginasComparison of Acute Effects Between Backbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Effect of Load Positioning On The KinemaDocumento40 páginasEffect of Load Positioning On The Kinemabrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- The Role of Rate of Force Development OnDocumento7 páginasThe Role of Rate of Force Development Onbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Effect of Hip Abduction Maximal VoluntarDocumento6 páginasEffect of Hip Abduction Maximal Voluntarbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- A Testing Battery For The Assessment ofDocumento11 páginasA Testing Battery For The Assessment ofbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Effect of Load Positioning On The KinemaDocumento40 páginasEffect of Load Positioning On The Kinemabrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Acute Effects of Drop Jump PotentiationDocumento7 páginasAcute Effects of Drop Jump Potentiationbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Prelipin's ChartDocumento3 páginasPrelipin's ChartElias Rosner100% (1)

- Crossfit - FoundationsDocumento8 páginasCrossfit - Foundationshikari70Ainda não há avaliações

- Uka-Michael Khmel&Tony Lester Classifying Sprint Training MethodsDocumento26 páginasUka-Michael Khmel&Tony Lester Classifying Sprint Training Methodsbrownsj1983100% (1)

- Movement PreparationDocumento44 páginasMovement Preparationbrownsj1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Summer Strength Manual 1Documento121 páginasSummer Strength Manual 1RoisinAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher workplan goals for professional growthDocumento6 páginasTeacher workplan goals for professional growthMichelle Anne Legaspi BawarAinda não há avaliações

- Reinforcement and Extinction of Operant BehaviorDocumento22 páginasReinforcement and Extinction of Operant BehaviorJazmin GarcèsAinda não há avaliações

- Law and MoralityDocumento14 páginasLaw and Moralityharshad nickAinda não há avaliações

- Window Into Chaos Cornelius Castoriadis PDFDocumento1 páginaWindow Into Chaos Cornelius Castoriadis PDFValentinaSchneiderAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor Unit Plan - Olsen SarahDocumento30 páginasWatercolor Unit Plan - Olsen Sarahapi-23809474850% (2)

- Letter of Rec (Dlsu)Documento2 páginasLetter of Rec (Dlsu)Luis Benjamin JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Creation of Teams For Crafting of School Learning Continuity PlaDocumento3 páginasCreation of Teams For Crafting of School Learning Continuity PlaRaymund P. CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Muhammad AURANGZEB: Academic QualificationDocumento3 páginasMuhammad AURANGZEB: Academic QualificationyawiAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Rupee SymbolDocumento9 páginasIndian Rupee SymboljaihanumaninfotechAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Speaking Section Question 3Documento14 páginasIntegrated Speaking Section Question 3manojAinda não há avaliações

- Admission Essay: Types of EssaysDocumento14 páginasAdmission Essay: Types of EssaysJessa LuzonAinda não há avaliações

- h5. Communication For Academic PurposesDocumento5 páginash5. Communication For Academic PurposesadnerdotunAinda não há avaliações

- Venn DiagramDocumento2 páginasVenn Diagramapi-255836042Ainda não há avaliações

- Patient Safety and Quality Care MovementDocumento9 páginasPatient Safety and Quality Care Movementapi-379546477Ainda não há avaliações

- Practice Test 6Documento9 páginasPractice Test 6Anonymous jxeb81uIAinda não há avaliações

- RESUMEDocumento2 páginasRESUMERyan Jay MaataAinda não há avaliações

- 4th Sem20212 Kushal SharmaDocumento7 páginas4th Sem20212 Kushal SharmaKushal SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- 00000548c PDFDocumento90 páginas00000548c PDFlipAinda não há avaliações

- Ued496 Ashley Speelman LessonpreparationplanninginstructingandassessingDocumento6 páginasUed496 Ashley Speelman Lessonpreparationplanninginstructingandassessingapi-440291829Ainda não há avaliações

- The scientific study of human origins, behavior, and cultureDocumento2 páginasThe scientific study of human origins, behavior, and cultureSuman BaralAinda não há avaliações

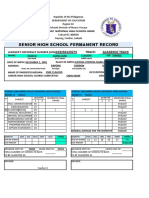

- Form 137 Senior HighDocumento5 páginasForm 137 Senior HighZahjid Callang100% (1)

- Vedantu Chemistry Mock Test Paper 1 PDFDocumento10 páginasVedantu Chemistry Mock Test Paper 1 PDFSannidhya RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Water Habitat DioramaDocumento2 páginasWater Habitat DioramaArjay Ian NovalAinda não há avaliações

- Classroom Strategies of Multigrade Teachers ActivityDocumento14 páginasClassroom Strategies of Multigrade Teachers ActivityElly CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Capstone Graduation Project Learning OutcomesDocumento11 páginasCapstone Graduation Project Learning OutcomesAhmed MohammedAinda não há avaliações

- Ranking T1 TIIDocumento2 páginasRanking T1 TIICharmaine HugoAinda não há avaliações