Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Jerry Fodor - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Enviado por

David Lu GaffyDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Jerry Fodor - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Enviado por

David Lu GaffyDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

1 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Jerry Fodor is one of the principal philosophers of mind of the

late twentieth and early twenty-first century. In addition to

having exerted an enormous influence on virtually every

portion of the philosophy of mind literature since 1960,

Fodors work has had a significant impact on the development

of the cognitive sciences. In the 1960s, along with Hilary

Putnam, Noam Chomsky, and others, he put forward

influential criticisms of the behaviorism that dominated much

philosophy and psychology at the time. Since then, Fodor has

articulated and defended an alternative, realist conception of

intentional states and their content that he argues vindicates

the core elements of folk psychology within a physicalist

framework.

Fodor has developed two theories that have been particularly

influential across disciplinary boundaries. He defends a

Representational Theory of Mind, according to which

mental states are computational relations that organisms bear to mental representations that are

physically realized in the brain. On Fodors view, these mental representations are internally

structured much like sentences in a natural language, in that they have both syntactic structure

and a compositional semantics. Fodor also defends an influential hypothesis about mental

architecture, namely, that low-level sensory systems (and language) are modular, in the sense

that theyre informationally encapsulated from the higher-level central systems responsible

for belief formation, decision-making, and the like. Fodors work on modularity has been

especially influential among evolutionary psychologists, who go much further than Fodor in

claiming that the systems underlying even high-level cognition are modular, a view that Fodor

himself vehemently resists.

Fodor has also defended a number of other influential views. He was an early proponent of the

claim that mental properties are functional properties, defined by their role in a cognitive system

and not by the physical material that constitutes them. Alongside functionalism, Fodor defended

an early and influential version of non-reductive physicalism, according to which mental

properties are realized by, but not reducible to, physical properties of the brain. Fodor has also

long been a staunch defender of nativism about the structure and contents of the human mind,

arguing against a variety of empiricist theories and famously arguing that all lexical concepts are

innate. When it comes to a theory of concepts, Fodor has vigorously argued against all versions

of inferential role semantics in philosophy and psychology. Fodors own view is what he calls

informational atomism, according to which lexical concepts are internally unstructured and

have their content in virtue of standing in certain external, informational relations to

properties instantiated in the environment.

Table of Contents

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

2 of 21

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Biography

Physicalism, Functionalism, and the Special Sciences

Intentional Realism

The Representational Theory of Mind

Content and Concepts

Nativism

Modularity

References and Further Reading

Jerry Fodor was born in New York City in 1935. He received his A.B. from Columbia University

in 1956 and his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1960. His first academic position was at MIT,

where he taught in the Departments of Philosophy and Psychology until 1986. He was

Distinguished Professor at CUNY Graduate Center from 1986 to 1988, when he moved to Rutgers

University where he has remained ever since. He is currently the State of New Jersey Professor of

Philosophy and Cognitive Science.

Throughout his career Fodor has subscribed to physicalism, the claim that all the genuine

particulars and properties in the world are either identical to or in some sense determined by

and dependent upon physical particulars and properties. Although there are many questions

about how physicalism should be formulated and understoodfor instance, what physical

means and whether the relevant determination/dependency relation is supervenience (Kim

1993) or realization (Melnyk 2003, Shoemkaer 2007)theres widespread acceptance of some

or other version of physicalism among philosophers of mind. To accept physicalism is to deny

that psychological and other non-basic properties float free from the fundamental physical

properties. Thus, acceptance of physicalism goes hand in hand with a rejection of mind-body

dualism.

Some of Fodors early work (1968, 1975) aimed (i) to show that mentalism was a genuine

alternative to dualism and behaviorism, (ii) to show that behaviorism had a number of serious

shortcomings, (iii) to defend functionalism as the appropriate physicalist metaphysics

underlying mentalism, and (iv) to defend a conception of psychology and other special sciences

according to which higher-level laws and the properties that figure in them are irreducible to

lower-level laws and properties. Lets consider each of these in turn.

For much of the twentieth century, behaviorism was widely regarded as the only viable

physicalist alternative to dualism. Fodor helped to change that, in part by drawing a clear

distinction between mere mentalism, which posits the existence of internal, causally efficacious

mental states, and dualism, which is mentalism plus the view that mental events require a special

kind of substance. Heres Fodor in his classic book Psychological Explanation:

[P]hilosophers who have wanted to banish the ghost from the machine have usually sought

to do so by showing that truths about behavior can sometimes, and in some sense, logically

implicate truths about mental states. In so doing, they have rather strongly suggested that

the exorcism can be carried through only if such a logical connection can be made out.

[O]nce it has been made clear that the choice between dualism and behaviorism is not

exhaustive, a major motivation for the defense of behaviorism is removed: we are not

required to be behaviorists simply in order to avoid being dualists (1968, pp. 58-59).

Fodor thus argues that theres a middle road between dualism and behaviorism. Attributing

mental states to organisms in explaining how they get around in and manipulate their

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

3 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

environments need not involve the postulation of a mental substance different in kind from

physical bodies and brains. In Fodors view, behaviorists influenced by Wittgenstein and Ryle

ignored the distinction between mentalism and dualismas he puts it, confusing mentalism

with dualism is the original sin of the Wittgensteinian tradition (Fodor, 1975, p. 4).

In addition to clearly distinguishing mentalism from dualism, Fodor put forward a number of

trenchant objections to behaviorism and the various arguments for it. He argued, for instance,

that neither knowing about the mental states of others nor learning a language with mental

terms requires that there be a logical connection, that is, a deductively valid connection, between

mental and behavioral terms, thus undermining a number of epistemological and linguistic

arguments for behaviorism (Fodor and Chihara 1965, Fodor 1968). Perhaps more importantly,

Fodor argued that theories in cognitive psychology and linguistics provide a powerful argument

against behaviorism, since they posit the existence of various mental events that are not

definable in terms of, or otherwise logically connected to, overt behavior (Fodor 1968, 1975).

Along with the arguments of Putnam (1963, 1967) and Chomsky (1959), among others, Fodors

early arguments against behaviorism were an important step in the development of the then

emerging cognitive sciences.

Central to this development was the rise of functionalism as a genuine alternative to

behaviorism, and Fodors Psychological Explanation (1968) was one of the first in-depth

treatments and defenses of this view (see also Putnam 1963, 1967). Unlike behaviorism, which

attempts to explain behavior in terms of law-like relationships between stimulus inputs and

behavioral outputs, functionalism posits that such explanations will appeal to internal properties

that mediate between inputs and outputs. Indeed, the main claim of functionalism is that mental

properties are individuated in terms of the various causal relations they enter into, where such

relations are not restricted to mere input-output relations, but also include their relations to a

host of other properties that figure in the relevant empirical theories. Although, at the time, the

distinctions between various forms of functionalism werent as clear as they are now, Fodors

brand of functionalism is a version of what is now known as psycho-functionalism. On this

view, what determines the relations that define mental properties are the deliverances of

empirical psychology, and not, say, the platitudes of commonsense psychology, what can be

known a priori about mental properties, or the analyticities expressive of the meanings of mental

expressions; see Rey (1997, ch.7) and Shoemaker (2003) for discussion.

By defining mental properties in terms of their causal roles, functionalists allow for different

kinds of physical phenomena to satisfy these relations. Functionalism thus goes hand in hand

with multiple realizability. In other words, if a given mental property, M, is a functional property

thats defined by a specific causal condition, C, then any number of distinct physical properties,

P1, P2, P3 Pn, may each realize M provided that each property meets C. Functionalism thereby

characterizes mental properties at a level of abstraction that ignores differences in the physical

structure of the systems that have these properties. Early functionalists, like Fodor and Putnam,

thus took themselves to be articulating a position that was distinct not only from behaviorism,

but also from type-identity theory, which identifies mental properties with neurophysiological

properties of the brain. If functionalism implies that mental properties can be realized by

different physical properties in different kinds of systems (or the same system over time), then

functionalism precludes identifying mental properties with physical properties.

Fodors functionalism, in particular, was articulated so that it was seen to have sweeping

consequences for debates concerning reductionism and the unity of science. In his seminal essay

Special Sciences (1974), Fodor spells out a metaphysical picture of the special sciences that

eventually came to be called non-reductive physicalism. This picture is physicalist in that it

accepts what Fodor calls the generality of physics, which is the claim that every event that falls

under a special science predicate also falls under a physical predicate, but not vice versa. Its

non-reductionist in that it denies that the special sciences should reduce to physical theories in

the long run (1974, p. 97). Traditionally, reductionists sought to articulate bridge laws that link

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

4 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

special science predicates with physical predicates, either in the form of bi-conditionals or

identity statements. Fodor argues not only that the generality of physics does not require the

existence of bridge laws, but that in general such laws will be unavailable given that the events

picked out by special science predicates will be wildly disjunctive from the perspective of

physics (1974, p. 103). Multiple realizability thus guarantees that special science predicates will

cross-classify phenomena picked out by purely physical predicates. This, in turn, undermines the

reductionist hope of a unified science whereby the higher-level theories of the special sciences

reduce to lower-level theories and ultimately to fundamental physics. On Fodors picture, then,

the special sciences are autonomous in that they articulate irreducible generalizations that

quantify over irreducible and casually efficacious higher-level properties (1974; see also 1998b,

ch.2).

Functionalism and non-reductive physicalism are now commonplace in philosophy of mind, and

provide the backdrop for many contemporary debates about psychological explanation, laws,

multiple realizability, mental causation, and more. This is something for which Fodor surely

deserves much of the credit (or blame, depending on ones view; see Kim (1993) and Heil (2003)

for criticisms of the metaphysical underpinnings of non-reductive physicalism).

A central aim of Fodors work has been to defend folk psychology as at least the starting point for

a serious scientific psychology. At a minimum, folk psychology is committed to two kinds of

states: belief-like states, which represent the environment and guide ones behavior, and

desire-like states, which represent ones goals and motivate behavior. We routinely appeal to

such states in our common-sense explanations of peoples behavior. For example, we explain

why John walked to the store in terms of his desire for milk and his belief that theres milk for

sale at the store. Fodor is impressed by the remarkable predictive power of such belief-desire

explanations. The following passage is typical:

Common sense psychology works so well it disappears. Its like those mythical Rolls Royce

cars whose engines are sealed when they leave the factory; only its better because they arent

mythical. Someone I dont know phones me at my office in New York fromas it might

beArizona. Would you like to lecture here next Tuesday? are the words he utters. Yes

thank you. Ill be at your airport on the 3 p.m. flight are the words that I reply. Thats all that

happens, but its more than enough; the rest of the burden of predicting behaviorof

bridging the gap between utterances and actionsis routinely taken up by the theory. And

the theory works so well that several days later (or weeks later, or months later, or years

later; you can vary the example to taste) and several thousand miles away, there I am at the

airport and there he is to meet me. Or if I dont turn up, its less likely that the theory failed

than that something went wrong with the airline. The theory from which we get this

extraordinary predictive power is just good old common sense belief/desire psychology. If

we could do that well with predicting the weather, no one would ever get his feet wet; and yet

the etiology of the weather must surely be childs play compared with the causes of behavior.

(1987, pp. 3-4)

Passages like this may suggest that Fodors intentional realism is wedded to the

folk-psychological categories of belief and desire. But this isnt so. Rather, Fodors claim is

that there are certain core elements of folk psychology that will be shared by a mature scientific

psychology. In particular, a mature psychology will posit states with the following features:

(1) They will be intentional: they will be about things and they will be semantically

evaluable. (In the way that the belief that Obama is President is about Obama, and can be

semantically evaluated as true or false.)

(2) They will be causally efficacious, figuring in genuine causal explanations and laws.

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

5 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Fodors intentional realism thus doesnt require that the folk-psychological categories themselves

find a place in a mature psychology. Indeed, Fodor has suggested that the individuation

conditions for beliefs are so vague and pragmatic that its doubtful theyre fit for empirical

psychology (1990, p. 175). What Fodor is committed to is the claim that a mature psychology will

be intentional through and through, and that the intentional states it posits will be causally

implicated in law-like explanations of human behavior. Exactly which intentional states will

figure in a mature psychology is a matter to be decided by empirical inquiry, not by a priori

reflection on our common sense understanding.

Fodors defense of intentional realism is usefully viewed as part of a rationalist tradition that

stresses the human minds striking sensitivity to indefinitely many arbitrary properties of the

world. Were sensitive not only to abstract properties such as being a democracy and being

virtuous, but also to abstract grammatical properties such as being a noun phrase and being a

verb phrase, as well as to such arbitrary properties as being a tiny folded piece of paper, being

an oddly-shaped canteen, being a crumpled shirt, and being to the left of my favorite mug. On

Fodors view, something can selectively respond to such properties only if its an intentional

system capable of manipulating representations of these properties.

Of course, there are many physical systems that are responsive to environmental properties (

thermometers, paramecia) that we would not wish to count as intentional systems. Fodors own

proposal for what distinguishes intentional systems from the rest is that only intentional systems

are sensitive to non-nomic properties, that is, the properties of objects that do not determine

that they fall under any laws of nature (Fodor 1986). Consider Fodors example of the property of

being a crumpled shirt. Although laws govern crumpled shirts, no object is subsumed under a

law in virtue of being a crumpled shirt. Nevertheless, the property of being a crumpled shirt is

one that we can represent an object as having, and such representations do enter into laws of

nature. For instance, theres presumably a law-like relationship between my noticing the

crumpled shirt, my desire to remark upon it, and my saying theres a crumpled shirt. On

Fodors view the job of intentional psychology is to articulate the laws governing mental

representations, which figure in genuine causal explanations of peoples behavior (Fodor 1987,

1998a).

Although positing mental representations that have semantic and causal properties states that

satisfy (1) and (2) abovemay not seem particularly controversial, the existence of causally

efficacious intentional states has been denied by all manner of behaviorists, epiphenomenalists,

Wittgensteinians, interpretationists, instrumentalists, and (at least some) connectionists. Much

of Fodors work has been devoted to defending intentional realism against such views as they

have arisen in both philosophy and psychology. In addition to defending intentional realism

against the behaviorism of Skinner and Ryle (Fodor 1968, 1975, Fodor et al. 1974), Fodor has

also defended it against the threat of epiphenomenalism (Fodor 1989), against Wittgenstein and

other defenders of the private language argument (Fodor and Chihara 1965, Fodor 1975),

against the eliminativism of the Churchlands (Fodor 1987, 1990), against the instrumentalism of

Dennett (Fodor 1981a, Fodor and Lepore 1992), against the interpretationism of Davidson

(Fodor 1990, Fodor and Lepore 1992, Fodor 2004), and against certain versions of connectionism

(Fodor and Pylyshyn 1988, Fodor and McLaughlin 1990, Fodor 1998b).

Even if Fodor is right that there are intentional states that satisfy (1) and (2), theres still the

question of how such states can exist in a physical world. Intentional realists must explain, for

instance, how lawful relations between intentional states can be understood physicalistically.

This is particularly pressing, since at least some intentional laws describe rational relations

between the intentional states they quantify over, and, ever since Descartes, philosophers have

worried about how a purely physical system could exhibit rational relations (see Lowe (2008) for

recent skepticism from a non-Cartesian dualist). Fodors Representational Theory of Mind is his

attempt to answer such worries.

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

6 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

As Fodor points out, RTM is really a loose confederation of theses that lacks, to put it mildly, a

canonical formulation (1998a, p. 6). At its core, though, RTM is an attempt to combine Alan

Turings work on computation with intentional realism (as outlined above). Broadly speaking,

RTM claims that mental processes are computational processes, and that intentional states are

relations to mental representations that serve as the domain of such processes. On Fodors

version of RTM, these mental representations have both syntactic structure and a compositional

semantics. Thinking thus takes place in an internal language of thought.

Turing showed us how to construct a purely mechanical device that could transform

syntactically-individuated symbols in such a way as to respect the semantic relations that exist

between the meanings, or contents, of those symbols. Formally valid inferences are the

paradigm. For instance, modus ponens can be realized on a machine thats sensitive only to

syntactic properties of symbols. The device thus doesnt have access to the symbols semantic

properties, but can nevertheless transform the symbols in a truth-preserving way. Whats

interesting about this, from Fodors perspective, is that, at least sometimes, mental processes

also involve chains of thoughts that are truth-preserving. As Fodor puts it:

[I]f you start out with a true thought, and you proceed to do some thinking, it is very often

the case that the thoughts that thinking leads you to will also be true. This is, in my view, the

most important fact we know about minds; no doubt its why God bothered to give us any.

(1994, p. 9; see also 1987, pp. 12-14, 2000, p. 18)

In order to account for this most important fact, RTM claims that thoughts themselves are

syntactically-structured representations, and that mental processes are computational processes

defined over them. Given that the syntax of a representation is what determines its causal role in

thought, RTM thereby serves to connect the fact that mental processes are truth-preserving with

the fact that theyre causal.

For instance, suppose a thinker believes that if John ran, then Mary swam. According to RTM,

for a thinker to hold such a belief is for the thinker to stand in a certain computational relation to

a mental representation that means if John ran, then Mary swam. Now suppose the thinker

comes to believe that John ran, and as a result comes to believe that Mary swam. RTM has it that

the causal relations between these thoughts hold in virtue of the syntactic form of the underlying

mental representations. By picturing the mind as a syntax-driven machine (Fodor, 1987, p. 20),

RTM thus promises to explain how the causal relations among thoughts can respect rational

relations among their contents. It thereby provides a potentially promising reply to Descartes

worry about how rationality could be exhibited by a mere machine. As Fodor puts it:

So we can now (maybe) explain how thinking could be both rational and mechanical.

Thinking can be rational because syntactically specified operations can be truth preserving

insofar as they reconstruct relations of logical form; thinking can be mechanical because

Turing machines are machines. [T]his really is a lovely idea and we should pause for a

moment to admire it. Rationality is a normative property; that is, its one that a mental

process ought to have. This is the first time that there has ever been a remotely plausible

mechanical theory of the causal powers of a normative property. The first time ever. (2000,

p. 29)

In Fodors view, its a major argument in favor of RTM that it promises an explanation of how

mental processes can be truth-preserving (Fodor 1994, p. 9; 2000, p. 13), and a major strike

against traditional empiricist and associationist theories that they offer no competing

explanation (1998a, p. 10; 2000, pp. 15-18; 2003, pp. 90-94).

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

7 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

That it explains how truth-preserving mental processes could be realized causally is one of

Fodors main arguments for RTM. In addition, Fodor argues that RTM provides the only hope of

explaining the so-called productivity and systematicity of thought (Fodor 1987, 1998a, 2008).

Roughly, productivity is the feature of our minds whereby there is no upper bound to the number

of thoughts we can entertain. We can think that the dog is on the deck; that the dog, which

chased the squirrel, is on the deck; that the dog, which chased the squirrel, which foraged for

nuts, is on the deck; and so on, indefinitely. There are, of course, thoughts whose contents are so

long that other factors prevent us from entertaining them. But abstracting away from such

performance limitations, it seems that a theory of our conceptual competence must account for

such productivity. Thought also appears to be systematic, in the following sense: a mind that is

capable of entertaining a certain thought, p, is also capable of entertaining logical permutations

of p. For example, minds that can entertain the thought that the book is to the left of the cup can

also entertain the thought that the cup is to the left of the book. Although its perhaps possible

that there could be minds that do not exhibit such systematicitya possibility denied by some,

for example, Evans (1982) and Peacocke (1992)it at least appears to be an empirical fact that

all minds do.

In Fodors view, RTM is the only theory of mind that can explain productivity and systematicity.

According to RTM, mental states have internal, constituent structure, and the content of mental

states is determined by the content of their constituents and how those constituents are put

together. Given a finite base of primitive representations, our capacity to entertain endlessly

many thoughts can be explained by positing a finite number of rules for combining

representations, which can be applied endlessly many times in the course of constructing

complex thoughts. RTM offers a similar explanation of systematicity. The reason that a mind that

can entertain the thought that the book is to the left of the cup can also entertain the thought that

the cup is to the left of the book, is that these thoughts are built up out of the same constituents,

using the same rules of combination. RTM thus explains productivity and systematicity because

it claims that mental states are relations to representations that have syntactic structure and a

compositional semantics. One of Fodors main arguments against alternative, connectionist

theories is that they fail to account for such features (Fodor and Pylyshyn 1988, Fodor 1998b,

chs. 9 and10).

A further argument Fodor offers in favor of RTM is that successful empirical theories of various

non-demonstrative inferences presuppose a system of internal representations in which such

inferences are carried out. For instance, standard theories of visual perception attempt to explain

how a percept is constructed on the basis of the physical information available and the visual

systems built-in assumptions about the environment, or natural constraints (Pylyshyn 2003).

Similarly, theories of sentence perception and comprehension require that the language system

be able to represent distinct properties (for instance, acoustic, phonological, and syntactic

properties) of a single utterance (Fodor et al. 1974). Both sorts of theories require that there be a

system of representations capable of representing various properties and serving as the medium

in which such inferences are carried out. Indeed, Fodor sometimes claims that the best reason

for endorsing RTM is that some version or other of RTM underlies practically all current

psychological research on mentation, and our best science is ipso facto our best estimate of what

there is and what its made of (Fodor 1987, p. 17). Fodors The Language of Thought (1975) is

the locus classicus of this style of argument.

Even if taking mental processes to be computational shows how rational relations between

thoughts can be realized by purely casual relations among symbols in the brain, as RTM

suggests, theres still the question of how those symbols come to have their meaning or content.

Ever since Brentano, philosophers have worried about how to integrate intentionality into the

physical world, a worry that has famously led some to accept the baselessness of intentional

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

8 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

idioms and the emptiness of a science of intention (Quine 1960, p. 221). Part of Fodors task is

thus to show, contra his eliminativist, instrumentalist, and interpretationist opponents, that a

plausible naturalistic account of intentionality can be given. Much of his work over the last two

decades or so has focused on this representational (as opposed to the computational)

component of RTM (Fodor 1987, 1994, 1998; Fodor and Lepore 1992, 2002).

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, Fodor endorsed a version of so-called inferential role

semantics (IRS), according to which the content of a representation is (partially) determined by

the inferential connections that it bears to other representations. To take two hoary examples,

IRS has it that bachelor gets its meaning, in part, by bearing an inferential connection to

unmarried, and kill gets its meaning, in part, by bearing an inferential connection to die.

Such inferential connections hold, on Fodors early view, because bachelor and kill have

complex structure at the level at which theyre semantically interpreted that is, they have the

structure exhibited by the phrases unmarried adult male and cause to die (Katz and Fodor

1963). In terms of concepts, the claim is that the concept BACHELOR has the internal structure

exhibited by UNMARRIED ADULT MALE, and the concept KILL has the internal structure

exhibited by CAUSE TO DIE. (This article follows the convention of writing the names of

concepts in capitals and writing the meanings of concepts in italics.)

Eventually, Fodor came to think that there are serious objections to IRS. Some of these

objections were based on his own experimental work in psycholinguistics, which he took to

provide strong evidence against the existence of complex lexical structure. Understanding a

sentence does not seem to involve recovering the decompositions of the lexical items they

contain (Fodor et al. 1975). Thinking the thought CATS CHASE MICE doesnt seem to be harder

than thinking CATS CATCH MICE, whereas the former ought to be more complex if chase can

be decomposed into a structure that includes intends to catch (Fodor et al. 1980). As Fodor

recently quipped, [i]ts an iron law of cognitive science that, in experimental environments,

definitions always behave exactly as though they werent there (1998a, p. 46). (For an

alternative interpretation of this evidence, see Jackendoff (1983, pp. 125-127; 1992, p. 49), and

Miller and Johnson-Laird (1976, p. 328).) In part because of the lack of evidence for

decompositional structure, Fodor at one point seriously considered the view the inferential

connections among lexical items may hold in virtue of inference rules, or meaning postulates,

which renders IRS consistent with a denial of the claim that lexical items are semantically

structured (1975, pp. 148-152).

However, Fodor ultimately became convinced of Quines influential arguments against meaning

postulates, and more generally, Quines view that there is no principled distinction between

those connections that are constitutive of the meaning of a concept and those that are merely

collateral. Quinean considerations, Fodor argues, show that IRS theorists should not appeal to

meaning postulates (Fodor 1998a, appendix 5a). Moreover, Quines confirmation holism

suggests that the epistemic properties of a concept are potentially connected to the epistemic

properties of every other concept, which, according to Fodor, suggests that IRS inevitably leads

to semantic holism, the claim that all of a concepts inferential connections are constitutive. But

Fodor argues that semantic holism is unacceptable, since its incompatible with the claim that

concepts are shareable. As he recently put it, since practically everybody has some eccentric

beliefs about practically everything, holism has it that nobody shares any concepts with anybody

else (2004, p. 35; see also Fodor and Lepore 1992, Fodor 1998a). This implication would

undermine the possibility of genuine intentional generalizations in psychology, which require

that concepts are shared across both individuals and different time-slices of the same individual.

Proponents of IRS might reply to these concerns about semantic holism by claiming that only

some inferential connections are concept-constitutive. But Fodor suggests that the only way to

distinguish the constitutive connections from the rest is to endorse an analytic/synthetic

distinction, which in his view Quine has given us good reason to reject (for example, 1990, p. x,

1998a, p. 71, 1998b, pp. 32-33). Fodors Quinean point, ultimately, is that theorists should be

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

9 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

reluctant to claim that there are certain beliefs people must hold, or inferences they must accept,

in order to possess a concept. For thinkers can apparently have any number of arbitrarily strange

beliefs involving some concept, consistent with them sharing that concept with others. As Fodor

puts it:

[P]eople can have radically false theories and really crazy views, consonant with our

understanding perfectly well, thank you, which false views they have and what radically

crazy things it is that they believe. Berkeley thought that chairs are mental, for Heavens

sake! Which are we to say he lacked, the concept MENTAL or the concept CHAIR? (1987, p.

125) (For further reflections along similar lines, see Williamson 2007.)

Without an analytic/synthetic distinction, any attempt to answer such a question would be

unprincipled. Rejecting the analytic/synthetic distinction thus leads Fodor to reject any

molecularist attempt to specify only certain inferences or beliefs as concept-constitutive. On

Fodors view, then, proponents of IRS are faced with two unequally satisfying options: they can

agree with Quine about the analytic/synthetic distinction, but at the cost of endorsing semantic

holism and its unpalatable consequences for the viability of intentionality psychology; or they

can deny semantic holism at the cost of endorsing an analytic/synthetic distinction, which Fodor

thinks nobody knows how to draw.

Its worth pointing out that Fodor doesnt think that confirmation holism, all by itself, rules out

the existence of certain local semantic connections that hold as a matter of empirical fact.

Indeed, contemporary battles over the existence of such connections are now taking place on

explanatory grounds that involve delicate psychological and linguistic considerations that are

fairly far removed from the epistemological considerations that motivated the positivists. For

instance, there are the standard convergences in peoples semantic-cum-conceptual intuitions,

which cry out for an empirical explanation. Although some argue that such convergences are best

explained by positing analyticities ( Grice and Strawson 1956, Rey 2005), Fodor argues that all

such intuitions can be accounted for by an appeal to Quinean centrality or one-criterion

concepts (Fodor 1998a, pp. 80-86). There are also considerations in linguistics that bear on the

existence of an empirically grounded analytic/synthetic distinction including issues concerning

the syntactic and semantic analyses of causative verbs, the generativity of the lexicon, and the

acquisition of certain elements of syntax. Fodor has engaged linguists on a number of such

fronts, arguing against the proposals of Jackendoff (1992), Pustejovsky (1995), Pinker (1989),

Hale and Keyser (1993), and others, defending the Quinean line (see Fodor 1998a, pp. 49-56, and

Fodor and Lepore 2002, chs. 5-6; see Pustejovsky 1998 and Hale and Keyser 1999 for

rejoinders). Fodors view is that all of the relevant empirical facts about minds and language can

be explained without any analytic connections, but merely deeply believed ones, precisely as

Quine argued.

Fodor sees a common error to all versions of IRS because they are trying to tie semantics to

epistemology. Moreover, the problems plaguing IRS ultimately arise as a result of its attempt to

connect a theory of meaning with certain epistemic conditions of thinkers. A further argument

against such views, Fodor claims, is that such epistemic conditions do not compose, since they

violate the compositionality constraint that is required for an explanation of productivity and

systematicity (see above). For instance, if one believes that brown cows are dangerous, then the

concept BROWN COW will license the inference BROWN COW DANGEROUS; but this

inference is not determined by the inferential roles of BROWN and COW, which it ought to be if

meaning-constituting inferences are compositional (Fodor and Lepore 2002, ch.1; for discussion

and criticism, see, for example, Block 1993, Boghossian 1993, and Rey 1993).

Another epistemic approach, as favored by many psychologists, appeals to prototypes.

According to these theories, lexical concepts are internally structured and specify the

prototypical features of their instances, that is, the features that theyre instances tend to (but

need not) have (for examples see Rosch and Mervis 1975). Prototype theories are epistemic

accounts because having a concept is a matter of knowing the features of its prototypical

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

10 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

instances. Given this, Fodor argues that prototype theories are in danger of violating

compositionality. For example, knowing what prototypical pets (dogs) are like and what

prototypical fish (trout) are like does not guarantee that you know what prototypical pet fish

(goldfish) are like (Fodor 1998a, pp. 102-108, Fodor and Lepore 2002, ch. 2). Since

compositionality is required in order to explain the productivity and systematicity of thought,

and prototype structures do not compose, it follows that concepts dont have prototype structure.

According to Fodor, the same kind argument applies to theories that take concepts to be

individuated by certain recognitional capacities. Fodor argues that since recognitional capacities

dont compose, but concepts do, there are no recognitional conceptsnot even red (Fodor

1998b, ch. 4). This argument has been disputed by a number of philosophers, for example,

Horgan (1998), Recanati (2002), and Prinz (2002).

Fodor thus rejects all theories that individuate concepts in terms of their epistemic relations and

their internal structure, and instead defends what he calls informational atomism, according to

which lexical concepts are unstructured atoms whose content is determined by certain

informational relations they bear to phenomena in the environment. In claiming that lexical

concepts are internally unstructured, Fodors informational atomism is meant to respect the

evidence and arguments against decomposition, definitions, prototypes, and the like. In claiming

that none of the epistemic properties of concepts are constitutive, Fodor is endorsing what he

sees as the only alternative to a molecularist and holistic theory of content, neither of which he

takes to be viable. By separating epistemology from semantics in this way, Fodors theory places

virtually no constraints on what a thinker must believe in order to possess a particular concept.

For instance, what determines whether a mind possesses DOG isnt whether it has certain beliefs

about dogs, but rather whether it possess an internal symbol that stands in the appropriate

mind-world relation to the property of being a dog. Rather than talking about concepts as they

figure in beliefs, inferences, or other epistemic states, Fodor instead talks of mere tokenings of

concepts, where for him these are internal symbols that need not play any specific role in

cognition. In his view, this is the only way for a theory of concepts to respect Quinean strictures

on analyticity and constitutive conceptual connections. Indeed, Fodor claims that by denying

that the grasp of any interconceptual relations is constitutive of concept possession,

informational atomism allows us to see why Quine was right about there not being an

analytic/synthetic distinction (Fodor 1998a, p. 71).

Fodors most explicit characterization of the mind-world relation that determines content is his

asymmetry dependency theory (1987, 1990). According to this theory, the concept DOG means

dog because dogs cause tokenings of DOG, and non-dogs causing tokenings of DOG is

asymmetrically dependent upon dogs causing DOG. In other words, non-dogs wouldnt cause

tokenings of DOG unless dogs cause tokenings of DOG, but not vice versa. This is Fodors

attempt to meet Brentanos challenge of providing a naturalistic sufficient condition for a symbol

to have a meaning. Not surprisingly, many objections have been raised to Fodors asymmetric

dependency theory (seethe papers in Loewer in Rey 1991), and its interesting to note that the

theory has all but disappeared from his more recent work on concepts and content, in which he

simply claims that meaning is information (more or less), without specifying the nature of the

relations that determine the informational content of a symbol (1998a, p. 12).

Regardless of the exact nature of the content-determining laws, its important to see that Fodor is

not claiming that the epistemic properties of concept are irrelevant from the perspective of a

theory of concepts. For such epistemic properties are what sustain the laws that lock concepts

onto properties in the environment. For instance, it is only because thinkers know a range of

facts about dogswhat they look like, that they bark, and so forththat their dog-tokens are

lawfully connected to the property of being a dog. Knowledge of such facts plays a causal role in

fixing the content of DOG, but on Fodors view they dont play a constitutive one. For while such

epistemic properties mediate the connection between tokens of DOG and dogs, this a mere

engineering fact about us, which has no implications for the metaphysics of concepts or

concept possession (1998a, p. 78). As Fodor puts it, its that your mental structures contrive to

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

11 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

resonate to doghood, not how your mental structures contrive to resonate to doghood, that is

constitutive of concept possession (1998a, p. 76). Although the internal relations that DOG

bears to other concepts and to percepts are what mediate the connection between DOG and dogs,

such relations are not concept-constitutive.

Fodors theory is thus a version of semantic externalism, according to which the meaning of a

concept is exhausted by its reference. There are two well-known problems with any such theory:

Frege cases, which putatively show that concepts that have different meanings can nevertheless

be referentially identical; and Twin cases, which putatively show that concepts that are

referentially distinct can nevertheless have the same meaning. Together, Frege cases and Twin

cases suggest that meaning and reference are independent in both directions. Fodor has had

much to say about each kind of case, and his views on both have changed over the years.

If conceptual content is exhausted by reference, then two concepts with the same referent ought

to be identical in content. As Fodor puts it, if meaning is information, then coreferential

representations must be synonyms (1998a, p. 12). But, prima facie, this is false. For as Frege

pointed out, its easy to generate substitution failures involving coreferential concepts: John

believes that Hesperus is beautiful may be true while John believes that Phosphorus is

beautiful is false; Thales believes that theres water in the cup may be true while Thales

believes that theres H2O in the cup is false; and so on. Since its widely believed that

substitution tests are tests for synonymy, such cases suggest that coreferential concepts arent

synonyms. In light of this, Fregeans introduce a layer of meaning in addition to reference that

allows for a semantic distinction between coreferential but distinct concepts. On their view,

coreferential concepts are distinct because they have different senses, or modes of presentation

of a referent, which Fregeans typically individuate in terms of conceptual role (Peacocke 1992).

In one of Fodors important early articles on the topic, Methodological Solipsism Considered as

a Research Strategy in Cognitive Psychology (1980), he argued that psychological explanations

depend upon opaque taxonomies of mental states, and that we must distinguish the content of

coreferential terms for the purposes of psychological explanation. At that time Fodor thus

allowed for a kind of content thats determined by the internal roles of symbols, which he

speculated might be reconstructed as aspects of form, at least insofar as appeals to content

figure in accounts of the mental causation of behavior (1981, p. 240). However, once he adopted

a purely externalist semantics (Fodor 1994), Fodor could no longer allow for a notion of content

determined by such internal relations. If conceptual content is exhausted by reference, as

informational semantics has it, then there cannot be a semantic distinction between coreferential

but distinct concepts.

In later work Fodor thus proposes to distinguish coreferential concepts purely syntactically, and

argues that we treat modes of presentation (MOPs) as the representational vehicles of thoughts

(Fodor 1994, 1998a, 2008). For instance, while Thales water-MOP has the same content as his

H2O-MOP (were he to have one), they are nevertheless syntactically distinct (for example, only

the latter has hydrogen as a constituent), and will thus differ in the causal and inferential

relations they enter into. In taking MOPs to be the syntactically-individuated vehicles of thought,

Fodors treatment of Frege cases serves to connect his theory of concepts with RTM. As he puts

it:

Its really the basic idea of RTM that Turings story about the nature of mental processes

provides the very candidates for MOP-hood that Freges story about the individuation of

mental states independently requires. If thats true, its about the nicest thing that ever

happened to cognitive science (1998a, p. 22).

An interesting consequence of this treatment is that peoples behavior in Frege cases can no

longer be given an intentional explanation. Instead, such behavior is explained at the level of

syntactically-individuated representations If, as Fodor suggested in his early work (1981),

psychological explanations standardly depend upon opaque taxonomies of mental states, then

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

12 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

this treatment of Frege cases would threaten the need for intentional explanations in psychology.

In an attempt to block this threat, Fodor (1994) argues that Frege cases are in fact quite rare, and

can be understood as exceptions rather than counterexamples to psychological laws couched in

terms of broad content. The viability of a view that combines a syntactic treatment of Frege cases

with RTM has been the focus of a fair amount of recent literature; see Arjo (1997), Aydede

(1998), Aydede and Robins (2001), Brook and Stainton (1997), Rives (2009), Segal (1997), and

Schneider (2005).

Let us now turn to Fodors treatment of Twin cases. Putnam (1975) asks us to imagine a place,

Twin Earth, which is just like earth except the stuff Twin Earthians pick out with the concept

water is not H2O but some other chemical compound XYZ. Consider Oscar and Twin Oscar, who

are both entertaining the thought theres water in the glass. Since theyre physical duplicates,

theyre type-identical with respect to everything mental inside their heads. However, Oscars

thought is true just in case theres H2O in the glass, whereas Twin Oscars thought is true just in

case theres XYZ in the glass. A purely externalist semantics thus seems to imply that Oscar and

Twin Oscars WATER concepts are of distinct types, despite the fact that Oscar and Twin Oscar

are type-identical with respect to everything mental inside their heads. Supposing that

intentional laws are couched in terms of broad content, it would follow that Oscars and Twin

Oscars water-directed behavior dont fall under the same intentional laws.

Such consequence have seemed unacceptable to many, including Fodor, who in his book

Psychosemantics (1987) argues that we need a notion of narrow content that allows us to

account for the fact that Oscars and Twin-Oscars mental states will have the same causal powers

despite differences in their environments. Fodor there defends a mapping notion of narrow

content, inspired by David Kaplans work on demonstratives, according to which the narrow

content of a concept is a function from contexts to broad contents (1987, ch. 2). The narrow

content of Oscars and Twin Oscars concept WATER is thus a function that maps Oscars context

onto the broad content H2O and Twin Oscars context onto the broad content XYZ. Such narrow

content is shared because Oscar and Twin Oscar are computing the same function. It was

Fodors hope that this notion of narrow content would allow him to respect the standard

Twin-Earth intuitions, while at the same time claim that the intentional properties relevant for

psychological explanation supervene on facts internal to thinkers.

However, in The Elm and the Expert (1994) Fodor gives up on the notion of narrow content

altogether, and argues that intentional psychology need not worry about Twin cases. Such cases,

Fodor claims, only show that its conceptually (not nomologically) possible that broad content

doesnt supervene on facts internal to thinkers. One thus can not appeal to such cases to argue

against the nomological supervenience of broad content on computation since, as far as anybody

knows chemistry allows nothing that is as much like water as XYZ is supposed to be except

water (1994, p. 28). So since Putnams Twin Earth is nomologically impossible, and empirical

theories are responsible only to generalizations that hold in nomologically possible worlds, Twin

cases pose no threat to a broad content psychology (1994, p. 29). If it turned out that such cases

did occur, then, according to Fodor, the generalizations missed by a broad content psychology

would be purely accidental (1994, pp. 30-33). Fodors settled view is thus that Twin cases, like

Frege cases, cases are fully compatible with an intentional psychology that posits only two

dimensions to concepts: syntactically-individuated internal representations and broad contents.

In The Language of Thought (1975), Fodor argued not only in favor of RTM but also in favor of

the much more controversial view that all lexical concepts are innate. Fodors argument starts

with the noncontroversial claim that in order to learn a concept one must learn its meaning, or

content. Empiricist models of concept learning typically assume that thinkers learn a concept on

the basis of experience by confirming a hypothesis about its meaning. But Fodor argues that such

models will apply only to those concepts whose meanings are semantically complex. For

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

13 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

instance, if the meaning of BACHELOR is unmarried, adult, male, then a thinker can learn

bachelor by confirming the hypothesis that it applies to things that are unmarried, adult, and

male. Of course, being able to formulate this hypothesis requires that one possess the concepts

UNMARRIED, ADULT, and MALE. The empiricist model thus will not apply to primitive

concepts that lack internal structure that can be mentally represented in this way. For instance,

one can not formulate the hypothesis that red things fall under RED unless one already has RED,

for the concept RED is a constituent of that very hypothesis. Primitive concepts like RED,

therefore, must not be learned and must be innate. If, as Fodor argues, all lexical concepts are

primitive, then it follows that all lexical concepts are innate (1975, ch. 2). Fodors claim is not

that people are born possessing lexical concepts; experience must play a role on any account of

concept acquisition (just as it does on any account of language acquisition). Fodors claim is that

concepts are not learned on the basis of experience, but rather are triggered by it. As Fodor

sometimes puts it, the relation between experience and concept acquisition is brute-causal, not

rational or evidential (Fodor 1981b).

Of course, most theories of conceptssuch as inferential role and prototype theories, discussed

aboveassume that many lexical concepts have some kind of internal structure. In fact, theorists

are sometimes explicit that their motivation for positing complex lexical structure is to reduce

the number of primitives in the lexicon. As Ray Jackendoff says:

Nearly everyone thinks that learning anything consists of constructing it from previously

known parts, using previously known means of combination. If we trace the learning process

back and ask where the previously known parts came from, and their previously know parts

came from, eventually we have to arrive at a point where the most basic parts are not

learned: they are given to the learner genetically, by virtue of the character of brain

development. Applying this view to lexical learning, we conclude that lexical concepts

must have a compositional structure, and that the word learners [functional]-mind is

putting meanings together from smaller parts (2002, 334). (See also Levin and Pinker 1991,

p. 4.)

Its worth stressing that while those in the empiricist tradition typically assume that the

primitives are sensory concepts, those who posit complex lexical structure need not commit

themselves to any such claim. Rather, they may simply assume that very few lexical items are not

decomposable, and deal with the issue of primitives on a case by case basis, as Jackendoff (2002)

does. In fact, many of the (apparent) primitives appealed to in the literaturefor example,

EVENT, THING, STATE, CAUSE, and so forthare quite abstract and thus not ripe for an

empiricist treatment.

In any case, Fodor is led to adopt informational atomism, in part, because he isnt persuaded by

the evidence that lexical concepts have any structure, decompositional or otherwise. He thus

does not think that appealing to lexical structure provides an adequate reply to his argument for

concept nativism (Fodor 1981b, 1998a, Fodor and Lepore 2002). If lexical concepts are primitive,

and primitive concepts are unlearned, then lexical concepts are unlearned.

In his book Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong (1998a), Fodor worries about

whether his earlier view is adequate. In particular, hes concerned about whether it has the

resources to explain questions such as why it is experiences with doorknobs that trigger the

concept DOORKNOB:

[T]heres a further constraint that whatever theory of concepts we settle on should satisfy: it

must explain why there is so generally a content relation between the experience that

eventuates in concept attainment and the concept that the experience eventuates in

attaining. [A]ssuming that primitive concepts are triggered, or that theyre caught, wont

account for their content relation to their causes; apparently only induction will. But

primitive concepts cant be induced; to suppose that they are is circular. (1998a, p. 132

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

14 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Fodors answer to this worry involves a metaphysical claim about the nature of the properties

picked out by most of our lexical concepts. In particular, he claims that its constitutive of these

properties that our minds lock to them as a result of experience with their stereotypical

instances. As Fodor puts it, being a doorknob is just being the kind of thing that our kinds of

minds (do or would) lock to from experience with instances of the doorknob stereotype (1998a,

p. 137). By making such properties mind-dependent in this way, Fodor thus provides a

metaphysical reply to his worry above: there need not be a cognitive or evidential relation

between our experiences with doorknobs and our acquisition of DOORKNOB, for being a

doorknob just is the property that our minds lock to as a result of experiencing stereotypical

instances of doorknobs. Fodor sums up his view as follows:

[I]f the locking story about concept possession and the mind-dependence story about the

metaphysics of doorknobhood are both true, then the kind of nativism about doorknob that

an informational atomist has to put up with is perhaps not one of concepts but of

mechanisms. That consequence may be some consolation to otherwise disconsolate

Empiricists. (1998a, p. 142)

In his recent book, LOT 2: The Language of Thought Revisited (2008), Fodor extends his earlier

discussions of concept nativism. Whereas his previous argument turned on the empirical claim

that lexical concepts are internally unstructured, Fodor now says that this claim is superfluous:

What I should have said is that its true and a priori that the whole notion of concept learning is

per se confused (2008, p. 130). Fodor thus argues that even patently complex concepts, such as

GREEN OR TRIANGULAR, are unlearnable. Learning this concept would require confirming the

hypothesis that the things that fall under it are either green or triangular. However, Fodor says:

[T]he inductive evaluation of that hypothesis itself requires (inter alia) bringing the property

green or triangular before the mind as such. You cant represent something as green or

triangular unless have the concepts GREEN, OR, and TRIANGULAR. Quite generally, you

cant represent anything as such as such unless you already have the concept such and such.

This conclusion is entirely general; it doesnt matter whether the target concept is

primitive (like green) or complex (like GREEN OR TRIANGULAR). (2008, p. 139)

Fodors diagnosis of this problem is that standard learning models wrongly assume that

acquiring a concept is a matter of acquiring beliefs Instead, Fodor suggests that beliefs are

constructs out of concepts, not the other way around, and that the failure to recognize this is

what leads to the above circularity (2008, pp. 139-140; see also Fodors debate with Piaget in

Piattelli-Palmarini, 1980).

Fodors story about concept nativism in LOT 2 runs as follows: although no conceptsnot even

complex onesare learned, concept acquisition nevertheless involves inductive generalizations.

We acquire concepts as a result of experiencing their stereotypical instances, and learning a

stereotype is an inductive process. Of course, if concepts were stereotypes then it would follow

that concept acquisition would be an inductive process. But, Fodor says, concepts cant be

stereotypes since stereotypes violate compositionality (see above). Instead, Fodor suggests that

learning a stereotype is a stage in the acquisition of a concept. His picture thus looks like this

(2008, p. 151):

Initial state (P1) stereotype formation (P2) locking (= concept attainment).

Why think that P1 is an inductive process? Fodor says there are well-known empirical results

suggesting that even very young infants are able to recognize and respond to statistical

regularities in their environments, and a genetically endowed capacity for statistical induction

would make sense if stereotype formation is something that minds are frequently employed to

do (2008, p. 153). What makes this picture consistent with Fodors claim that there cant be

any such thing as concept learning (p. 139) is that he does not take P2 to be an inferential or

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

15 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

intentional process (pp. 154-155). What kind of process is it? Here, Fodor doesnt have much to

say, other than its the kind of thing that our sort of brain tissue just does: Psychology gets you

from the initial state to P2; then neurology takes over and gets you the rest of the way to concept

attainment (p. 152). So, again, Fodors ultimate story about concept nativism is consistent with

the view, as he puts it in Concepts, that maybe there arent any innate ideas after all (1998a, p.

143). Instead, there are innate mechanisms, which he now claims take us from the acquisition of

stereotypes to the acquisition of concepts.

In his influential book, The Modularity of Mind (1983), Fodor argues that the mind contains a

number of highly specialized, modular systems, whose operations are largely independent from

each other and from the central system devoted to reasoning, belief fixation, decision making,

and the like. In that book, Fodor was particularly interested in defending a modular view of

perception against the so-called New Look psychologists and philosophers (for example,

Bruner, Kuhn, Goodman), who took cognition to be more or less continuous with perception.

Whereas New Look theorists focused on evidence suggesting various top-down effects in

perceptual processing (ways in which what people believe and expect can affect what they see),

Fodor was impressed by evidence from the other direction suggesting that perceptual processes

lack access to such background information. Perceptual illusions provide a nice illustration. In

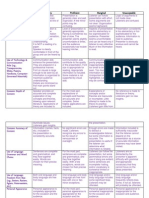

the famous Mller-Lyer illusion (Figure 1), for instance, the top line looks longer than the bottom

line even though theyre identical in length.

Figure 1. The Mller-Lyer Illusion

Standard explanations of the illusion appeal to certain background assumptions the visual

system is making, which effectively override the fact that the retinal projections are identical in

length. However, as Fodor pointed out, if knowing that the two lines are identical in length does

not change the fact that one looks longer than the other, then clearly perceptual processes dont

have access to all of the information available to the perceiver. Thus, there must be limits on how

much information is available to the visual system for use in perceptual inferences. In other

words, vision must be in some interesting sense modular. The same goes for other sensory/input

systems, and, on Fodors view, certain aspects of language processing.

Fodor spells out a number of characteristic features of modules. That knowledge of an illusion

doesnt make the illusion go away illustrates one of their central features, namely, that they are

informationally encapsulated. Fodor says:

[T]he claim that input systems are informationally encapsulated is equivalent to the claim

that the data that can bear on the confirmation of perceptual hypotheses includes, in the

general case, considerably less that the organism may know. That is, the confirmation

function for input systems does not have access to all the information that the organism

internally represents. (1983, p. 69)

In addition, modules are supposed to be domain specific, in the sense that theyre restricted in

the sorts of representations (such as visual, auditory, or linguistic) that can serve as their inputs

(1983, pp. 47-52). Theyre also mandatory. For instance, native English speakers cannot hear

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

16 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

utterances of English as mere noise (You all know what Swedish and Chinese sound like; what

does English sound like? 1983, p. 54), and people with normal vision and their eyes open cannot

help but see the 3-D objects in front of them. In general, modules approximate the condition so

often ascribed to reflexes: they are automatically triggered by the stimuli that they apply to

(1983, pp. 54-55). Not only are modular processes domain-specific and out of our voluntary

control, theyre also exceedingly fast. For instance, subjects can shadow speech (repeat what is

heard when its heard) with a latency of about 250 milliseconds, and match a description to a

picture with 96% accuracy when exposed for a mere 167 milliseconds (1983, pp. 61-64). In

addition, modules have shallow outputs, in the sense that the information they carry is simple,

or constrained in some way, which is required because otherwise the processing required to

generate them couldnt be encapsulated. As Fodor says, if the visual system can deliver news

about protons, then the likelihood that visual analysis is informationally encapsulated is

negligible (1983, p. 87). Fodor tentatively suggests that the visual system delivers as outputs

basic perceptual categories (Rosch et al. 1976) such as dog or chair, although others take

shallow outputs to be altogether non-conceptual (see Carruthers 2006, p. 4). In addition to these

features, Fodor also suggests that modules are associated with fixed neural architecture (1983,

pp. 98-99), exhibit characteristic and specific breakdown patterns (1983, pp. 99-100), and have

an ontogeny that exhibits a characteristic pace and sequencing (1983, pp. 100-101).

On Fodors view, although sensory systems are modular, the central systems underlying belief

fixation, planning, decision-making, and the like, are not. The latter exhibit none of the

characteristic features associated with modules since they are domain-general, unencapsulated,

under our voluntary control, slow, and not associated with fixed neural structures. Fodor draws

attention, in particular, to two distinguishing features of central systems: theyre isotropic, in the

sense that in principle, any of ones cognitive commitments (including, of course, the available

experiential data) is relevant to the (dis)confirmation of any new belief (2008, p. 115); and

theyre Quinean, in the sense that they compute over the entirety of ones belief system, as when

one settles on the simplest, most conservative overall beliefas Fodor puts it, the degree of

confirmation assigned to any given hypothesis is sensitive to properties of the entire belief

system (1983, p. 107). Fodors picture of mental architecture is one in which there are a number

of informationally encapsulated modules that process the outputs of transducer systems, and

then generate representations that are integrated in a non-modular central system. The

Fodorean mind is thus essentially a big general-purpose computer, with a number of domainspecific computers out near the edges that feed into it.

Fodors work on modularity has been criticized on a number of fronts. Empiricist philosophers

and psychologists are typically quite happy with the claim that the central system is domaingeneral, but have criticized Fodors claim that input systems are modular (see Prinz 2006 for a

recent overview of such criticisms). Fodors work has also been attacked from the other direction,

by those who share his rationalist and nativist sympathies. Most notably, evolutionary

psychologists reject Fodors claim that there must be a non-modular system responsible for

integrating modular outputs, and argue instead that the mind is nothing but a collection of

modular systems (see, Barkow, Cosmides, and Tooby (1992), Carruthers (2006), Pinker (1997),

and Sperber (2002)). According to such massive modularity theorists, what Fodor calls the

central system is in fact built up out of a number of domain-specific modules, for example,

modules devoted to common-sense reasoning about physics, biology, psychology, and the

detection of cheaters, to name a few prominent examples from the literature. Evolutionary

psychologists also claim that these central modules are adaptations, that is, products of selection

pressures that faced our hominid ancestors; see Pinker (1997) for an introduction to evolutionary

psychology, and Carruthers (2006) for what is perhaps the most sophisticated defense of massive

modularity to date.

That Fodor is a nativist might lead one to believe that he is sympathetic to applying adaptationist

reasoning to the human mind. This would be a mistake. Fodor has long been skeptical of the idea

that the mind is a product of natural selection, and in his book The Mind Doesnt Work That

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

17 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Way (2001) he replies to a number of arguments purporting to show that it must be. For

instance, evolutionary psychologists claim that the mind must be reverse engineered: in order

to figure out how it works, we must know what its function is; and in order to know what its

function is we must know what it was selected for. Fodor rejects this latter inference, and claims

that natural selection is not required in order to underwrite claims about the teleology of the

mind. For the notion of function relevant for psychology might be synchronic, not diachronic:

You might think, after all, that what matters in understanding the mind is what ours do now,

not what our ancestors did some millions of years ago (1998b, p. 209). Indeed, in general, one

does not need to know about the evolutionary history of a system in order to make inferences

about its function:

[O]ne can often make a pretty shrewd guess what an organ is for on the basis of entirely

synchronic considerations. One might thus guess that hands are for grasping, eyes for seeing,

or even that minds are for thinking, without knowing or caring much about their history of

selection. Compare Pinker (1997, p. 38): psychologists have to look outside psychology if

they want to explain what the parts of the mind are for. Is this true? Harvey didnt have to

look outside physiology to explain what the heart is for. It is, in particular, morally certain

that Harvey never read Darwin. Likewise, the phylogeny of bird flight is still a live issue in

evolutionary theory. But, I suppose, the first guy to figure out what birds use their wings for

lived in a cave. (2000, p. 86)

Fodors point is that even if one grants that natural selection underwrites teleological claims

about the mind, it doesnt follow that in order to understand a psychological mechanism one

must understand the selection pressures that led to it.

Evolutionary psychologists also argue that the adaptive complexity of the human mind requires

that one treat it as a collection of adaptations. For natural selection is the only known

explanation for adaptive complexity in the living world. Fodor replies that the complexity of the

mind is irrelevant when it comes to determining whether its a product of natural selection:

[W]hat matters to the plausibility that the architecture of our minds is an adaptation is how

much genotypic alternation would have been required for it to evolve from the mind of the

nearest ancestral ape whose cognitive architecture was different from ours. [I]ts entirely

possible that quite small neurological reorganizations could have effected wild psychological

discontinuities between our minds and the ancestral apes. (2000, pp. 87-88)

Given that we dont currently know whether small neurological changes in the brains of our

ancestors led to large changes in their cognitive capacities, Fodor says, the appeal to adaptive

complexity does not warrant the claim that our minds are the product of natural selection. In his

latest book co-authored with Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, What Darwin Got Wrong (2010),

Fodor argues that selectional explanations in general are both decreasingly of interest in biology

and, on further reflection, actually incoherent. Perhaps needless to say, this view has occasioned

considerable controversy; for examples see Sober (forthcoming), Block and Kitcher (2010), and

Godfrey-Smith (2010).

In The Mind Doesnt Work That Way (2000), and also in LOT 2 (2008), Fodor reiterates and

defends his claim that the central systems are non-modular, and connects this view to general

doubts about the adequacy of RTM as a comprehensive theory of the human mind. One of the

main jobs of the central system is the fixation of belief via abductive inferences, and Fodor argues

that the fact that such inferences are isotropic and Quinean shows they cannot be realized in a

modular system. These features render belief fixation a holistic, global, and contextdependent affair, which implies that it is not realized in a modular, informationallyencapsulated system. Moreover, given RTMs commitment to the claim that computational

processes are sensitive only to local properties of mental representations, these holistic features

of central cognition would appear to fall outside of RTMs scope (2000, chs. 2-3; 2008, ch. 4).

28-Dec-13 3:12 AM

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fodor, Jerry Print

18 of 21

http://www.iep.utm.edu/fodor/print

Consider, for instance, the simplicity of a belief. As Fodor says: The thought that there will be no

wind tomorrow significantly complicates your arrangements if you had intended to sail to

Chicago, but not if your plan was to fly, drive, or walk there (2000, p. 26). Whether or not a

belief complicates a plan thus depends upon the beliefs involved in the planthat is, the

simplicity of a belief is one of its global, context-dependent properties. However, the syntactic

properties of representations are local, in the sense that they supervene on their intrinsic,

context-independent properties. To the extent that cognition involves global properties of

representations, then, Fodor concludes that RTM cannot provide a model of how cognition

works:

[A] cognitive science that provides some insight into the part of the mind that isnt modular