Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

AMEE Guide Supplements - Workplace-Based Assessment As An Educational Tool. Guide Supplement 31.1-Viewpoint1

Enviado por

Saeed Al-YafeiTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

AMEE Guide Supplements - Workplace-Based Assessment As An Educational Tool. Guide Supplement 31.1-Viewpoint1

Enviado por

Saeed Al-YafeiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2009; 31: 5960

AMEE guide supplements: Workplace-based

assessment as an educational tool. Guide

supplement 31.1 Viewpoint1

HOSSAM HAMDY

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Marshall University on 10/28/14

For personal use only.

University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Over the last two decades, important global reforms have

taken place in medical education at the undergraduate and

postgraduate levels. Emphasis on outcome based education

led to the development and refinement of performance based

assessment instruments and tools in order to assess these

outcomes (Friedman & Mennin 1991). All this has been linked

to the issue of quality and standards in medical education.

In the UK, the Calman and GMC Tomorrows Doctors

reports were key in the revolutionary change in undergraduate

and postgraduate training. The reports clearly stated that

supervision and feedback are crucial . . .. The integration of

theoretical teaching with practical work, progressive assessment and feedback to teachers and trainees are essential

(Calman 1993; General Medical Council 1993).

In the US, the Accreditation Committee of Graduate Medical

Educators (ACGME 2000) had a similar effect on residency

training programmes through the six general competencies for

evaluating residents.

The culture of training of doctors is changing from being

opportunistic to structured, planned cycles of activities,

blended with service and evaluating the trainees performance

and progress from one level to the next.

The assessment of what the trainee does in real life

on-the-job is what is now commonly described as workplacebased assessment or in-vivo assessment. This is in contrast to

in-vitro assessment which evaluates what the trainee can do

in controlled representations of practice such as the OSCE

(Rethans 1991).

In the UK, the Royal College of General Practitioners have

defined workplace-based assessment as: the evaluation of a

doctors progress over time in their performance in those areas

of professional practice best tested in the workplace

(Swanwick & Chana 2005; Deighan 2007). It should include

a process of collection of evidence of performance over the

difference phases of training.

As it is well known in education assessment drives

learning, workplace-based assessment plays a pivotal role in

aligning training and learning with assessment. On the Millers

pyramid of conceptual assessment of clinical competencies, it

represents measurement at the top of the pyramid, does in a

real work environment and a high degree of authenticity

(Miller 1990).

Workplace-based training has suffered at the undergraduate clerkship and postgraduates residency training levels

from lack of observaxtion of the trainee, poor assessment of

clinical competencies when encountering real patients and

no or poor feedback. In order to increase the effectiveness of

workplace-based training, these problems need to be

addressed and rectified.

The tasks performed by the trainee should be observed and

effective feedback provided; addressing the quality of

performance using defined criteria and description of specific

behaviour rather than general statements of good or bad

performance. The headline results of the BEME systematic

review on assessment, feedback and physicians clinical

performance indicated that feedback can change physicians

clinical performance when provided systematically over

multiple years by an authoritative credit source. (Veloski

et al. 2006).

The AMEE guide 31 on Workplace-based assessment as an

educational tool by Norcini & Burch (2007) gives a

comprehensive description of assessment tools commonly

used in North America and UK. The authors are well known

authorities in the field and have contributed to the development of some of the described instruments e.g. mini-CEX

(Norcini et al. 2003). The five sections of the guide cover the

main literature on the efficacy and prevalence of formative

assessment and feedback, common methods of workplacebased assessment, faculty development on how to be an

effective supervisor in giving feedback and challenges in

implementation.

In reading the Guide, I would like to highlight four points:

1.

2.

Workplace-based assessment is equally valuable for the

trainee and the trainer. It should be considered as an

integral component of an experiential learning cycle

which includes a planning phase, observation phase

and a reflection phase on performance expressed in

a constructive feedback to both the trainee and the

trainer leading to a new cycle of planning and

improvement of the training programme.

The Guide explicitly describes workplace-based assessment as a formative tool with a primary objective

of providing feedback based on observation of

Correspondence: Hossam Hamdy, College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Email: profhossamhamdy@yahoo.com

ISSN 0142159X print/ISSN 1466187X online/09/0100592 2009 Informa Healthcare Ltd.

DOI: 10.1080/01421590802298215

59

H. Hamdy

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by Marshall University on 10/28/14

For personal use only.

3.

4.

performance by the supervisors or other stakeholders;

multi-source feedback. Using these methods for

summative assessment needs better control of the

confounding variables, which are always related to

the real workplace environment and are directly linked

to the healthcare delivery system, context of practice

and variables in the complexity of the patients

problems encountered.

The mini-CEX, which has gained popularity in postgraduate settings, requires 1214 encounters with real

patients in order to achieve a reliability co-efficient of

0.8 (Norcini et al. 2003). The main advantage of this

method is its authenticity by using real patients. On the

other hand, it is important to notice that it assesses a

component of the encounter, not its totality. Another

method which is described in the literature and not

mentioned in the guide is the direct observation

clinical encounter examination (DOCE), described

by Hamdy et al. (2003) as a summative assessment

in the clerkship phase and on a final comprehensive

examination. Students encounter four real patients

with different health problems in different age groups.

Focused history taking, physical examination, reasoning, decision making and communication skills with

real patients are observed and assessed using a

checklist. The generalizability coefficient reported was

0.84 indicating high reliability. Although this method

was not reported in postgraduate residency programmes, it has potential for use as both a formative

and summative assessment method. Its main advantage

is evaluation of the encounter in its totality and the

small number of patients needed in sampling students

or trainees performance.

The guide emphasises the importance of training

faculty on how to use these methods, how to give

feedback and after collecting this information, what to

do with it. Before introducing these methods in

postgraduate or undergraduate medical education

programmes, effective training of faculty and supervisors should take place in order to ensure its successful

implementation and develop their skills in providing

high quality and honest feedback, particularly in the

face of poor and under-performers.

Applying these methods in a busy workplace is a difficult task

which necessitates the identification of interested clinical

60

educators who have the time or will give the time to supervise

the training and create a culture of observation of performance

and feedback.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of

interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and

writing of the paper.

Notes on contributor

Prof HOSSAM HAMDY is the Vice Chancellor for Medical & Health

Sciences College at the College of Medicine, University of Sharjah and

Professor of Surgery and Medical Education.

Note

1. This AMEE guide was published as: Norcini J, Burch V. 2007.

Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE

Guide no. 31. Med Teach 29:855871.

References

ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) 2000.

Outcome project: General competencies [on line]. Available at http://

www.acgme.org/outcome (accessed June 2007).

Calman KC. 1993. Medical education: A look into the future. Postgrad Med

Educ. 69(supplement 2):5355.

Deighan M. 2007. The learning and teaching guide (London, UK: Royal

College of General Practitioners).

Friedman M, Mennin SP. 1991. Rethinking critical issues in performance

assessment. Acad Med 66:390395.

General Medical Council. 1993. Tomorrows doctors: Recommendations on

undergraduate medical education (London, GMC).

Hamdy H, Prasad K, Williams R, Salih FA. 2003. Reliability and validity of

the direct observation clinical encounter examination (DOCEE).

Med Educ 37:205212.

Miller GE. 1990. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance.

Acad Med. 65:563567.

Norcini J, Blank L, Duffy FD, Fortina G. 2003. The mini-CEX: A method of

assessing clinical skills. Ann Intern Med 138:476481.

Norcini J, Burch V. 2007. Workplace-based assessment as an educational

tool: AMEE guide no 31. Med Teach 29:855871.

Rethans JJ. 1991. Does competence predict performance? Standardized

patients as a means to investigate the relationship between competence

and performance of general practitioners. Thesis (Amsterdam: Thesis)

Publishers.

Swanwick T, Chana N. 2005. Workplace assessment for licensing in general

practice. Discussion paper. Br J Gen Pract 6:461467.

Veloski J, Boex JR, Grusberger M, Evans A, Wolfson DB. 2006. BEME guide

no. 7. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and

physicians clinical performance. Med Teach 28:117128.

Você também pode gostar

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- How To Write A Journal ArticleDocumento50 páginasHow To Write A Journal ArticleSaeed Al-Yafei80% (5)

- Lesson Plan - Contemporary Arts From The PhilippinesDocumento4 páginasLesson Plan - Contemporary Arts From The PhilippinesEljay Flores96% (25)

- 22 Self-Actualization Tests & Tools To Apply Maslow's TheoryDocumento34 páginas22 Self-Actualization Tests & Tools To Apply Maslow's TheoryIbrahim HarfoushAinda não há avaliações

- Nephrology MCQsDocumento7 páginasNephrology MCQsSaeed Al-Yafei67% (6)

- Assessment Form 2 PDFDocumento1 páginaAssessment Form 2 PDFAgnes Bansil Vitug100% (1)

- Skelly S Mcqs in Tropical MedicineDocumento29 páginasSkelly S Mcqs in Tropical MedicineSaeed Al-Yafei92% (13)

- Cognitive PsychologyDocumento22 páginasCognitive PsychologySaeed Al-Yafei100% (6)

- How To Write A Scientific Original ArticleDocumento67 páginasHow To Write A Scientific Original ArticleSaeed Al-YafeiAinda não há avaliações

- Speak Out Intermediate Tests Track ListingDocumento1 páginaSpeak Out Intermediate Tests Track Listingbob43% (7)

- What Makes A Good TeacherDocumento4 páginasWhat Makes A Good TeacherJravi ShastriAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in AdultsDocumento8 páginasDiagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in AdultsSaeed Al-YafeiAinda não há avaliações

- Endnote 7 TrainingDocumento84 páginasEndnote 7 TrainingSaeed Al-Yafei100% (2)

- Preparatory Lecture: Confounding and BiasDocumento144 páginasPreparatory Lecture: Confounding and BiasSaeed Al-YafeiAinda não há avaliações

- Probability Calculation in MinesweeperDocumento2 páginasProbability Calculation in MinesweeperBrayan Perez ContrerasAinda não há avaliações

- Exam Steps and Process - Read FirstDocumento3 páginasExam Steps and Process - Read FirstDeejaay2010Ainda não há avaliações

- The Implications of The Dodo Bird Verdict For Training in Psychotherapy Prioritizing Process ObservationDocumento4 páginasThe Implications of The Dodo Bird Verdict For Training in Psychotherapy Prioritizing Process ObservationSebastian PorcelAinda não há avaliações

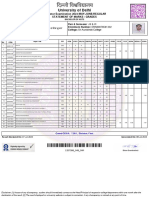

- University of Delhi: Semester Examination 2023-MAY-JUNE:REGULAR Statement of Marks / GradesDocumento2 páginasUniversity of Delhi: Semester Examination 2023-MAY-JUNE:REGULAR Statement of Marks / GradesFit CollegeAinda não há avaliações

- Information Brochure & Guidelines For Filling of Online Application Form For Recruitment of Non-Teaching Positions in Delhi UniversityDocumento106 páginasInformation Brochure & Guidelines For Filling of Online Application Form For Recruitment of Non-Teaching Positions in Delhi UniversityVidhiLegal BlogAinda não há avaliações

- Cambridge Aice Marine Science SyllabusDocumento32 páginasCambridge Aice Marine Science Syllabusapi-280088207Ainda não há avaliações

- Resume 2021 RDocumento3 páginasResume 2021 Rapi-576057342Ainda não há avaliações

- Mslearn dp100 14Documento2 páginasMslearn dp100 14Emily RapaniAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Theatre and Film Studies: Nnamdi Azikiwe UniversityDocumento7 páginasDepartment of Theatre and Film Studies: Nnamdi Azikiwe Universityanon_453956231Ainda não há avaliações

- Structure of Academic TextsDocumento22 páginasStructure of Academic TextsBehappy 89Ainda não há avaliações

- Drivers Ed Homework AnswersDocumento7 páginasDrivers Ed Homework Answersafnogtyaiergwk100% (1)

- Marketing Management Course OutlineDocumento3 páginasMarketing Management Course OutlineShehryar HumayunAinda não há avaliações

- Advisory Assignment Order Junior High SchoolDocumento1 páginaAdvisory Assignment Order Junior High SchoolJaz and Ysha's ChannelAinda não há avaliações

- GCSE New Spec Performance MarksheetDocumento2 páginasGCSE New Spec Performance MarksheetChris PowellAinda não há avaliações

- Algebraic FractionsDocumento11 páginasAlgebraic FractionsSafiya Shiraz ImamudeenAinda não há avaliações

- Building Your Weekly SDR Calendar-Peer Review Assignment-Mohamed AbdelrahmanDocumento3 páginasBuilding Your Weekly SDR Calendar-Peer Review Assignment-Mohamed AbdelrahmanrtwthcdjwtAinda não há avaliações

- Linux AdministrationDocumento361 páginasLinux AdministrationmohdkmnAinda não há avaliações

- Barnard College, Title IX, Dismissal LetterDocumento3 páginasBarnard College, Title IX, Dismissal LetterWhirlfluxAinda não há avaliações

- HR Questions InterviewDocumento54 páginasHR Questions InterviewAlice AliceAinda não há avaliações

- 4-ProjectCharterTemplatePDF 0Documento5 páginas4-ProjectCharterTemplatePDF 0maria shintaAinda não há avaliações

- YPD Guide Executive Summary PDFDocumento2 páginasYPD Guide Executive Summary PDFAlex FarrowAinda não há avaliações

- Bbfa4034 Accounting Theory & Practice 1: MAIN SOURCE of Reference - Coursework Test + Final ExamDocumento12 páginasBbfa4034 Accounting Theory & Practice 1: MAIN SOURCE of Reference - Coursework Test + Final ExamCHONG JIA WEN CARMENAinda não há avaliações

- Virtue Ethics FinalDocumento19 páginasVirtue Ethics FinalAlna JaeAinda não há avaliações

- PHD Ordinance Msubaroda IndiaDocumento15 páginasPHD Ordinance Msubaroda IndiaBhagirath Baria100% (1)

- Project 2 ExampleDocumento6 páginasProject 2 ExampleShalomAinda não há avaliações