Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

5 SPXX Butterfill 1.3

Enviado por

benalbDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

5 SPXX Butterfill 1.3

Enviado por

benalbDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

362

Awareness of belief

Stephen Butterfill

1.

Mindreading & Interpretation

An awareness of other peoples beliefs

plays an essential role in everyday life.

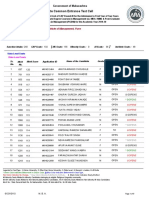

In this diagram, for example, Molly believes that its raining, and Tom is aware

of her belief. But what is awareness of

belief? What is involved in being able

to recognise and think about beliefs?

Here are two requirements:

Variation Requirement Being

aware of beliefs involves appreciating how different people may

have beliefs different from ones

own (including beliefs which are

inconsistent with ones own beliefs).

Its

raining

Molly thinks

that its

raining

Molly has a belief

Tom is aware of

Mollys belief

Truth Requirement Being aware of beliefs involves understanding

what it is for beliefs to be false.

Are these different requirements, in the sense that someone could satisfy one

without satisfying the other? No one could meet the Truth Requirement

without meeting the Variation Requirement, because understanding that a

belief is false involves realising one should not believe it and appreciating

the possibility of having other beliefs in its place. But could someone meet

the Variation Requirement without meeting the Truth Requirement? In other

words, is it possible to be aware of beliefs which are inconsistent without

being aware that at least one of these beliefs is false?

For instance, suppose Tom thinks it isnt raining, and suppose he is

aware of this belief and of Mollys belief that it is raining. One of these beliefs must be false: either Tom or Molly has a false belief, so Tom is aware

of a belief that is false. But does it necessarily follow that Tom can understand that one of these beliefs is false?

Some philosophers say yes, others say no. Donald Davidson would

say no, because he thinks that being aware of a belief involves being able

to appreciate the possibility of false belief. In fact, Davidson thinks that

merely having a belief requires understanding that it may be false. He says,

one cannot believe something, or doubt it, without knowing that what one

363

believes or doubts maybe either true or false, and in particular, that one may

be wrong (Davidson 1999: 12).

Opposing Davidsons view, Daniel Dennett claims that it is possible to

be aware of another persons beliefs without understanding that beliefs can

be false.1 As Dennett describes it, being aware of beliefs doesnt require

having any concepts at all. Instead, being aware of beliefs is a matter of being systematically sensitive to another persons beliefs in a range of practical ways (Dennett 1978: 275; 1987: 247). For example, purposefully engaging in deception would be a practical way of showing an appreciation of

potential differences in belief. So Dennett denies, whereas Davidson accepts, that awareness of belief necessarily involves understanding that beliefs can be false.

Davidson and Dennett also have different views about why awareness of

beliefs matters. For Dennett, the point of our being aware of other peoples

beliefs is to co-ordinate social interaction (see Dennett 1987: 50). On the

other hand, Davidson regards our capacity to be aware of others beliefs as

an essential part of understanding objects and events as inhabiting a world

shared by all but independent of any one person. For Davidson, awareness

of belief is defined by its role in enabling us to grasp that objects and events

are mind-independent, rather than by its role in facilitating social interaction

(Davidson 1991b: 201; 1991a: 164). This disagreement is relevant because

if coordinating social interaction is what awareness of belief is for, then

there is no reason to think it requires understanding the possibility that beliefs can be false. Since everyone acts on her own beliefs and modifies them

in the light of evidence available to her, it is irrelevant whose beliefs are

false from the point of view of co-ordinating interaction. All that matters are

differences in belief.

Who is right? Why is it important that we are aware of others beliefs,

and does this awareness require that we understand what it is for beliefs to

be false? The aim of this paper is to argue that there are two varieties of

awareness of belief, which Ill call mindreading and interpreting. Instead

of seeing Davidson and Dennett as saying conflicting things about a single

kind of awareness of belief, I think they are better understood as talking

about different kinds of awareness. Here is an initial characterisation:

Mindreading involves being sensitive to which beliefs a person has,

and knowing which actions her having these beliefs should lead to.

A mindreader knows how beliefs are acquired and what practical

consequences they have for action.

Interpreting involves using beliefs in giving reason-explanations.

An interpreter knows why someone should have particular beliefs,

and why these beliefs should lead to certain actions.

364

Are mindreading and interpreting really different? Most people probably

think there is just one kind of awareness of belief, and would assume that

my initial characterisations of mindreading and interpretation simply emphasise different aspects of a single ability. In this paper, I aim to make the

distinction between mindreading and interpretation theoretically viable, and

to argue that interpreting beliefs, but not mindreading them, necessarily involves understanding that beliefs can be false. Someone who mindreads beliefs will satisfy the Variation Requirement but not the Truth requirement,

whereas interpreting beliefs involves satisfying the Truth Requirement. So

whether it is possible to be aware of differences in belief without understanding what it is for a belief to be false depends on whether we are talking

about mindreading or interpretation.

2.

What is it for a belief to be true or false? Pragmatists

and Intellectualists

My question is whether being aware of differences in peoples beliefs involves understanding that beliefs can be false. This question has two moving parts: an answer depends both on what awareness of belief is, and on

what it is for a belief to be true or false.

We cant take the notion of truth for granted, because there is much disagreement about it. One major axis of disagreement is that between Pragmatists and Intellectualists. William James, a Pragmatist, explains the point

at issue:

Truth is a property of certain of our ideas. It means their

agreement, as falsity means their disagreement, with reality.

Pragmatists and intellectualists both accept this definition as a

matter of course. They begin to quarrel only after the question is

raised as to what may precisely be meant by the term agreement (1907: 76).

Ill describe the Pragmatists position first. In How to Make Our Ideas

Clear, Peirce explains the Pragmatists position roughly as follows.2 Accepting a belief establishes habits, which are dispositions to think and act

in various ways in different circumstances. Any belief can be distinguished

by the particular habits established by its acceptance. Furthermore, the

whole purpose of accepting a belief is to establish these habits: whatever

there is connected with a thought, but irrelevant to its purpose, is an accretion to it, but no part of it. So, the Pragmatist infers, To develop [a beliefs] meaning, we have, therefore, simply to determine what habits it produces, for what a thing means is simply what habits it involves. In other

words, the Pragmatist holds that the content of a belief is exhaustively determined by which habits accepting it would establish. This is a form of

functionalism about belief.

365

This account allows the Pragmatist to define what it is for a belief to

agree with reality in terms of the habits associated with it. Thus James,

presenting a view he regards himself as sharing with Peirce, says:

Pragmatism defines agreeing to mean certain ways of working, be they actual or potential. Thus, for my statement the

desk exists to be true of a desk recognized as real by you, it

must be able to lead me to shake your desk, to explain myself by

words that suggest that desk to your mind, to make a drawing

that is like the desk you see, etc (James 1911: 218; cf. 1907:

82, 1911: 191).

But exactly which ways of working constitute the agreement of an idea with

reality? The Pragmatist answers that when an idea works in a way that is

consistently beneficial to a thinker, the idea agrees with reality and is therefore true. So, for the Pragmatist:

Those thoughts are true which guide us to beneficial interaction with sensible particulars as they occur.3

The Pragmatists claim isnt just that true beliefs happen to guide us to

beneficial interaction, or that beneficial beliefs are likely to be true; anyone

can accept this. Rather, the Pragmatist is claiming that this is what it means

for beliefs to agree with reality.4

Where James talks about the agreement of a belief with reality, modern

Pragmatists like Ruth Millikan or David Papineau talk about the truthconditions of beliefs. Like Peirce and James, they regard beliefs as having

characteristic consequences for thought and action. They also hold that the

consequences of a belief can be judged successful or unsuccessful without

reference to the truth of that belief. Although different Pragmatists use different notions of success, the basic idea is that an action is successful if it

fulfils the agents intention in acting, and a belief is successful if it would

lead to successful action. Given these claims, the Pragmatist asserts that:

(P)

The truth-condition of a belief is that condition under which actions

that result rationally from the belief will normally succeed.

How does this work? Suppose we know that Molly has a particular belief, S,

and that we know which actions this belief causes, but that we dont know

which truth-condition her belief has. The Pragmatists claim is, in effect,

that a generalisation of the form:

(G)

All actions that are rational consequences of Mollys belief S will

succeed if and only if p

366

is equivalent to a statement of the form:

(T)

Mollys belief S is true if and only if p

In general, the Pragmatist claims that a beliefs truth-condition can be defined as whatever condition is required for the success of all actions reasonably caused by that belief.5 This is a contemporary reformulation of

James claim that a belief agrees with reality to the extent that it leads to

beneficial actions.

The Intellectualist objects that the Pragmatist gets things exactly the

wrong way around. Whereas the Pragmatist defines the truth-condition of a

belief in terms of its consequences, the Intellectualist claims that the truthcondition of a belief explains which actions someone who acts on that belief

should perform. For example, imagine its raining and Molly takes an umbrella because she wants to stay dry. The Intellectualist claims that we can

explain why Molly should take an umbrella in terms of the fact that she believes that taking an umbrella will keep her dry. So the Intellectualist treats

the following explanation as a paradigm:

(I1)

(I2)

(I3)

Molly believes that taking an umbrella will keep her dry.

Molly wants to stay dry.

Molly should take an umbrella.

As the Intellectualist understands it, this isnt a prediction of what Molly

will actually do; rather, justifies Mollys taking an umbrella. The Intellectualist asks why Mollys belief should cause her to take an umbrella, rather

than to call a taxi or stay at home. Her answer is that Mollys belief should

have this consequence because it is the belief that taking an umbrella will

keep her dry.

In general, the Intellectualist claims that the truth-condition of a belief

explains which actions that belief should result in. So knowing what a person believes gives us insight into why she acts, and this insight is not reducible to knowing which normal consequences her beliefs have. This is

incompatible with the Pragmatists way of defining truth-conditions for beliefs, because the Pragmatist defines the truth-condition of a belief as whatever condition guarantees the normal success of actions that are rational

consequences of that belief. So the Pragmatists explanation works in the

opposite direction:

(P2)

(P3)

(P1)

Molly wants to stay dry.

Molly should take an umbrella.

If Molly has a belief, S, which causes her to take an umbrella, then S is the belief that taking an umbrella will keep

her dry.

367

The Pragmatist wants to explain why Mollys belief is true if and only if

taking an umbrella will keep her dry. The Intellectualist, on the other hand,

wants to explain why Mollys having this particular belief makes it the case

that she should take an umbrella if she wants to stay dry. The Pragmatist and

Intellectualist positions are opposed because these two explanations cant be

combined.

So the Pragmatists argument with the Intellectualist concerning the nature of truth boils down to a question about the direction of explanation. The

question is, Do the reasonable consequences of a belief determine its truthcondition, or are they determined by its truth-condition? Put like this, the

debate between the Pragmatist and the Intellectualist seems to be not at all

relevant to my theme, which is awareness of belief. So why does it matter?

3.

Pragmatist mindreaders and Intellectualist

interpreters

To answer this question, we need to change our focus from considering

what it is for a belief to be true or false to considering what it is to think of a

belief as true or false. The Pragmatist and the Intellectualist present themselves as giving philosophical accounts of what it is for a belief to be true or

false, but in this section Ill argue that we can reinterpret them as giving accounts of what it is to be aware of beliefs as true or false. The Pragmatist is,

in effect, giving an account of what mindreading is, while the Intellectualist

is giving an account of interpreting.

Ill start with an analogy to illustrate how the argument is going to work.

Instead of beliefs, think about maps. Imagine using a map to find out where

Bielefeld University is. Knowing how to use the map involves being able to

look at the map and the landmarks around one in order to decide which way

to walk. In addition to knowing how to use maps, most of us probably also

know why they work, that is, why they can be used to find out where to

walk. Maps work because they represent our environment, and inaccurate

maps can mislead us because they misrepresent our environment. Knowing

why a map works enables us to justify the use we make of it to select a route

to the university: the maps representing our environment justifies us in using the map to decide where to walk.

Just as the Pragmatist explains what it is for a belief to have a particular

truth-condition, so she can give an analogous account of what it is for a map

to represent a particular place. In the case of beliefs, the Pragmatist identifies the truth-condition of a belief as that condition under which actions rationally based on it normally succeed. In the case of maps, the Pragmatist

says that a map represents that place in which using the map appropriately

will normally get you where you want to be (compare Dewey 1938: 402-3).

So, for instance:

368

(R*)

This map represents* Bielefeld if and only if following the map appropriately will normally get you wherever you want to be in Bielefeld.

This gives us a notion of representation for maps, which Ill call representation*. Is representation* the same as our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of

representation? Two things might make it seem plausible that it is:

(a)

(b)

If following a map doesnt normally get us where we want to be in

Bielefeld, then it cant represent Bielefeld.

If following a map normally gets us where we want to be in Bielefeld, then it must represent Bielefeld.

This shows that a map represents Bielefeld if and only if it represents*

Bielefeld. However, the two notions of representation are different. This is

because they play different roles in justifying our use of maps. Suppose we

meet someone who knows how to use maps to find her way around, but

doesnt understand why following a map gets her where she wants to be. For

her, the map is a kind of magic, or else she treats it as a brute fact that maps

can be used to navigate. Using our pre-theoretic notion of representation, we

can explain to her that the usual way of following the map should get her

where she wants to be because the map represents Bielefeld. However, our

explanation would be circular if we used the Pragmatists notion of representation*. For to say that the map represents* Bielefeld is just to say that a

particular way of following the map will to get us where we want to be. So

we cant explain why following the map gets us where we want to be in

terms of the Pragmatists notion of representation*. This shows that representation is not the same as representation*.

Now imagine someone who doesnt understand our ordinary, pretheoretic notion of representation, but does grasp the Pragmatists notion of

representation* for maps. This person is a practising Pragmatist with respect

to maps. She would be able to distinguish an incorrect from a correct map,

but she would not be able to explain the usefulness of a map in terms of its

representational properties. She would know how to use maps to navigate,

but she wouldnt know why they get her to where she wants to be. She can

mindread maps but not interpret them.

There is an analogous argument concerning the Pragmatists account of

truth-conditions for beliefs. Here is how the Pragmatists defines the truthcondition of a belief again:

(T*)

The truth*-condition of a belief is that condition under which actions

that result rationally from the belief will normally succeed.

369

Ive called what the Pragmatist defines truth* so that we can ask whether

truth* is like our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of truth for beliefs. Assume,

for the sake of argument, that a belief is true* under exactly the same conditions that it is true.6 Even on this assumption, truth* is not the same as truth.

This is because we use the notion of truth in some explanations of thought

and action in which the notion of truth* cant feature.

The example I gave earlier illustrates this. In the example, its raining

and Molly wants to stay dry whilst shes out and about. Molly has a belief

that is true if and only if taking an umbrella will keep her dry. This belief of

Mollys causes her to take an umbrella. But why should this belief of

Mollys cause her to take an umbrella? Why shouldnt this belief instead

cause her to call a taxi or wear an anorak? Why arent these rational consequences of Mollys belief? Intuitively, there is a simple answer to this question. Mollys belief should cause her to take an umbrella because it is the

belief that taking an umbrella will keep her dry. Which truth-condition

Mollys belief has explains why her having this belief should result in certain actions and not others. But the truth*-condition of Mollys belief cant

explain why this belief should cause her to take an umbrella. This is because

which truth*-condition Mollys belief has is determined by which actions it

should cause. So you cant use truth*-conditions to explain why something

is a rational consequence of a belief.7

This is the difference between the notions of truth and truth*. The notion

of truth can explain why particular beliefs should result in certain actions.

The notion of truth* cant do this, because its definition has already assumed the relevant facts about which actions a belief should result in. You

cant use a concept to explain something you have already assumed in defining that concept.8

We dont ordinarily think about truth in the way described by the Pragmatist. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the Pragmatist describes a perfectly

coherent way of thinking about beliefs. Imagine someone who doesnt understand our ordinary, pre-theoretic notion of truth for beliefs, but does understand the Pragmatists notion of truth*. I dont mean to suggest that this

person reflectively adheres to the Pragmatists philosophical claims about

truth*; rather, the Pragmatists theory describes how this person actually

thinks about beliefs in practice. She is a practising Pragmatist with respect

to beliefs.

The practising Pragmatist can appreciate that not all beliefs are true*, and

she can appreciate that different people may have different beliefs. She also

knows how beliefs work; that is, she knows under what conditions beliefs

are acquired, and what practical consequences beliefs tend to have for action. Nevertheless, she doesnt understand why beliefs have the consequences they do. She cant justify her own or other peoples actions in terms

of the truth*-conditions of their beliefs. If we assume (with the Intellectualist) that one of the functions of the concept of truth is to play this role, we

370

can say that she doesnt really understand what it is for a belief to be true,

even though she is aware of beliefs. This entails a qualified answer to the

question I started with: unless the Pragmatist is right about truth, a practising Pragmatist satisfies the Variation Requirement but not the Truth Requirement. And, irrespective of who is right, the Pragmatist and Intellectualist accounts of truth can be reinterpreted as theoretical descriptions of two

kinds of awareness of belief. Mindreading is the activity of thinking about

beliefs as if one were using the Pragmatists account of truth*, and Interpretation is thinking about beliefs in terms of the Intellectualists notion of

truth. Mindreaders are Pragmatists; interpreters are Intellectualists.9

Notes

1

2

3

4

5

In Conditions of Personhood (in Dennett 1978), he asserts that taking

the intentional stance towards another person does not require reflective

understanding of what one is doing.

How to Make Our Ideas Clear is reprinted in Peirce (1932).

James (1911: 82); cf. Peirce (1932: 247/5.387): truth is distinguished

from falsehood simply by this, that if acted on it should, on full consideration, carry us to the point we aim at and not astray.

James (1911: 154); cf. (1911: 219-220) and (1911: 273).

Papineau (1993: 3.7.v), (1993: 3.9) and Millikan (1984: 77), (1993:

72-73). I am ignoring these authors many refinements of the Pragmatists basic claim.

This is a point on which many arguments against pragmatism concentrate. Some argue that the Pragmatists account yields intuitively wrong

(Pietroski 1992) or non-realist truth-conditions (Forbes 1989; Peacocke

1992, 5.2). Even if the Pragmatist can answer these objections, this

doesnt show her account of truth is adequate.

Some philosophers present this kind of point as an objection to the Pragmatists account of truth (Godfrey-Smith 1996: 6.3; Johnston 1993),

without mentioning that some pragmatists explicitly endorse it as a consequence of their theories (James 1907: 85; Millikan 1993: 237).

For people who would object to this sentence, see the replies to Johnston

(1993) by Wright (1992, 130), Miller (1995), (1997), and Menzies and

Pettit (1993). These objections can be bypassed, because my argument

requires only that an explanation looses some of its justificatory depth if

it uses a concept to explain something already assumed in defining that

concept.

I have been helped enormously by comments and criticisms at GAP4,

and by many other people.

References

Bennett, Jonathan

1991 How To Read Minds in Behaviour in Andrew Whiten (ed.) Natural Theories of the Mind: evolution, development and simulation of

everyday mindreading, Oxford: Blackwell

371

Davidson, Donald

1991a Three Varieties of Knowledge in A. Griffiths (ed.) Memorial Essays for A. J. Ayer Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, Cambridge: University Press

1991b Epistemology Externalized, Dialectica vol. 45, no. 2-3

1999 The Emergence of Thought, Erkenntnis 51

Dennett, Daniel

1978 Brainstorms: philosophical essays on mind and psychology, Montgomery: Bradford Books

1987 The Intentional Stance, Cambridge, Mass: MIT

1998 Brainchildren, London: Penguin

Dewey, John (1938)

1938 The Theory of Inquiry, New York: Henry Holt and Co

Forbes, Graham

1989 Biosemantics and the Normative Properties of Thought, Philosophical Perspectives, vol. 3

Godfrey-Smith, Peter

1996 Complexity and the Function of Mind in Nature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

James, William

1907 Pragmatism: A new name for some old ways of thinking, New York:

Longman Green and Co

1911 The Meaning of Truth, New York: Longman Green and Co

Johnston, Mark

1993 Objectivity Refigured: Pragmatism Without Verificationism in

John Haldane and Crispin Wright (eds.), Reality, Representation and

Projection, Oxford: University Press

Miller, Alex

1995 Objectivity Disfigured: Mark Johnstons Missing Explanation Argument, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. LV, no. 4

1997 More Responses to the Missing Explanation Argument, Philosophia vol. 25

Millikan, Ruth

1984 Language, Thought, and Other Biological Categories, Cambridge,

Mass: MIT, 1984

1993 White Queen Psychology and Other Essays for Alice, Cambridge,

Mass: MIT, 1993

Papineau, David

1990 Truth and Teleology in Dudley Knowles (ed.) Explanation and Its

Limits, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

1993 Philosophical Naturalism, Oxford: Blackwell

Peacocke, Christopher

1992 A Study of Concepts, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

372

Peirce, Charles Sanders

1932 Pragmatism And Pragmaticism: Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce vol 5, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss (eds.), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Pietroski, Paul

1992 Intentionality and Teleological Error, Philosophical Quarterly vol.

73

Sinclair, Anne

1996 Young Childrens Practical Deceptions and Their Understanding of

False Belief, New Ideas in Psychology vol. 14, no. 2

Wright, Crispin

1992 The Euthyphro Contrast in Truth and Objectivity, Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press

Você também pode gostar

- Believe What YouwantDocumento19 páginasBelieve What YouwantmarcelolimaguerraAinda não há avaliações

- The Belief Quotient: How Your Beliefs Shape Your Life, And What You Can Do to Take ControlNo EverandThe Belief Quotient: How Your Beliefs Shape Your Life, And What You Can Do to Take ControlNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Scott-Kakures - On Belief & Captivity of The WillDocumento28 páginasScott-Kakures - On Belief & Captivity of The WillAyon MaharajAinda não há avaliações

- Difficult Arguments & Simple Truths: When Modern Day Afflictions Advance ExposuresNo EverandDifficult Arguments & Simple Truths: When Modern Day Afflictions Advance ExposuresAinda não há avaliações

- Know How and Acts of FaithDocumento17 páginasKnow How and Acts of FaithMuhamad Yusuf Rizqi HerdanaAinda não há avaliações

- Audi Robert Belief Faith AcceptanceDocumento16 páginasAudi Robert Belief Faith AcceptanceSimón Palacios BriffaultAinda não há avaliações

- The Epistemology of TrustDocumento3 páginasThe Epistemology of TrustArubaAinda não há avaliações

- Role of Belef in KnowledgeDocumento14 páginasRole of Belef in KnowledgeRyan RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Seeing What Is The Kind Thing To Do: Perception and Emotion in MoralityDocumento15 páginasSeeing What Is The Kind Thing To Do: Perception and Emotion in MoralityyoAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Thinking (2014) Notes & ExtractsDocumento4 páginasCritical Thinking (2014) Notes & ExtractsJorge VelillaAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 4Documento20 páginasUnit 4aishwaryapandey334Ainda não há avaliações

- Bouri Amine Orientation PHD Project Thesis Human SciencesDocumento5 páginasBouri Amine Orientation PHD Project Thesis Human SciencesAmine BouriAinda não há avaliações

- LiteraturereviewDocumento5 páginasLiteraturereviewapi-286307917Ainda não há avaliações

- EfoloiactivityDocumento7 páginasEfoloiactivityapi-287771244Ainda não há avaliações

- Some Observations On Cs PeirceDocumento7 páginasSome Observations On Cs PeirceBill MeachamAinda não há avaliações

- What Is TrustDocumento20 páginasWhat Is TrustHuman-Social DevelopmentAinda não há avaliações

- 0 1017@apa 2018 42Documento19 páginas0 1017@apa 2018 42RMFrancisco2Ainda não há avaliações

- 05 Donald Davidson - A Coherence Theory of Truth and KnowledgeDocumento10 páginas05 Donald Davidson - A Coherence Theory of Truth and KnowledgebryceannAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1 Definition and Nature of EpistemologyDocumento19 páginasUnit 1 Definition and Nature of EpistemologyJyoti YadavAinda não há avaliações

- Darkroom FinalDocumento132 páginasDarkroom FinalAxel DeguzmanAinda não há avaliações

- 8 Reflection DeflatedDocumento28 páginas8 Reflection DeflatedbenAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy A Text With Readings 12th Edition Manuel Velasquez Solutions ManualDocumento14 páginasPhilosophy A Text With Readings 12th Edition Manuel Velasquez Solutions Manualthoabangt69100% (32)

- Davies & Coltheart 2000Documento46 páginasDavies & Coltheart 2000José Eduardo PorcherAinda não há avaliações

- How To Build TrustDocumento5 páginasHow To Build TrustErika Parker100% (1)

- Epistemological Validity of Faith: Faith Is The ConfidentDocumento4 páginasEpistemological Validity of Faith: Faith Is The ConfidentnikhaarjAinda não há avaliações

- Belief and Normativity Pascal EngelDocumento25 páginasBelief and Normativity Pascal EngelmirandikiAinda não há avaliações

- Perception Empiricist FoundationalismDocumento4 páginasPerception Empiricist FoundationalismSHASHWAT SWAROOPAinda não há avaliações

- 2.3 Social and Political Climate: 3. The Value of TrustDocumento3 páginas2.3 Social and Political Climate: 3. The Value of TrustArubaAinda não há avaliações

- Theory of KnowledgeDocumento3 páginasTheory of KnowledgeRonel Rovera DalisayAinda não há avaliações

- .1 Motives-Based TheoriesDocumento4 páginas.1 Motives-Based TheoriesArubaAinda não há avaliações

- The Nature of Trust and TrustworthinessDocumento3 páginasThe Nature of Trust and TrustworthinessArubaAinda não há avaliações

- Reynolds - Doxastic Voluntarism and The Function of Epistemic EvaluationsDocumento17 páginasReynolds - Doxastic Voluntarism and The Function of Epistemic EvaluationsTiago SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Faith - A Study ofDocumento23 páginasFaith - A Study ofSantiago Daniel VillarrealAinda não há avaliações

- Epistemology Is A Study of KnowledgeDocumento4 páginasEpistemology Is A Study of KnowledgeCaryll JumawanAinda não há avaliações

- Belief As A Psychological TheoryDocumento3 páginasBelief As A Psychological TheoryRahul KandpalAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction Paper (Cognitivism Vs Non-Cognitivism)Documento2 páginasReaction Paper (Cognitivism Vs Non-Cognitivism)Natalie Francine CimanesAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Different Theories of TruthDocumento2 páginas3 Different Theories of TruthHadjie EstevesAinda não há avaliações

- LCFAITH Sample OnlyDocumento2 páginasLCFAITH Sample OnlyAlexius Aaron LlarenasAinda não há avaliações

- Persuasion: An Indispensable Skill For Business Today: by Brian O'C. LeggettDocumento4 páginasPersuasion: An Indispensable Skill For Business Today: by Brian O'C. LeggettCarlos Augusto Perez TrujilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Aim of BeliefDocumento43 páginasThe Aim of BeliefPsiholog Alina Mirela CraiuAinda não há avaliações

- Faith NotesDocumento46 páginasFaith NotesKervin Clark DavantesAinda não há avaliações

- What To Believe and How To Believe It?: Beliving MeaningDocumento14 páginasWhat To Believe and How To Believe It?: Beliving MeaningNatalia NeliAinda não há avaliações

- Methods of PhilosophizingDocumento14 páginasMethods of PhilosophizingRupelma Salazar PatnugotAinda não há avaliações

- Simpson - What Is TrustDocumento20 páginasSimpson - What Is Trustsrussell123Ainda não há avaliações

- Ifa As A Repository of KnowledgeDocumento16 páginasIfa As A Repository of KnowledgeOdeku OgunmolaAinda não há avaliações

- De SousaDocumento29 páginasDe SousaSimón Palacios BriffaultAinda não há avaliações

- Faith ExplainedDocumento31 páginasFaith ExplainedErwin SabornidoAinda não há avaliações

- METHODS IN PHILOSOPHIZING (PhiloM3Q1)Documento4 páginasMETHODS IN PHILOSOPHIZING (PhiloM3Q1)Joshua Lander Soquita CadayonaAinda não há avaliações

- The Concept of Belief in Egan 1986Documento36 páginasThe Concept of Belief in Egan 1986AnnaAinda não há avaliações

- Explaining Our Own Beliefs (Philosophical Studies)Documento34 páginasExplaining Our Own Beliefs (Philosophical Studies)Munir BazziAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Theories of TruthDocumento3 páginas3 Theories of Truthshukri MohamedAinda não há avaliações

- The Correspondence Theory of TruthDocumento3 páginasThe Correspondence Theory of Truthbiji kshetriAinda não há avaliações

- Three Different Theories of TruthDocumento4 páginasThree Different Theories of TruthkAinda não há avaliações

- Magical Nature of BeliefsDocumento7 páginasMagical Nature of BeliefsMohammed IsmailAinda não há avaliações

- Civics G12ho&ws PDFDocumento3 páginasCivics G12ho&ws PDFNas GoAinda não há avaliações

- DocumentDocumento2 páginasDocumentAnneliece Erica AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Changing Core Beliefs PDFDocumento17 páginasChanging Core Beliefs PDFjeromedaviesAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Thinking 1. IntroductionDocumento23 páginasCritical Thinking 1. IntroductionDonnel Alexander100% (1)

- What Is Ethical RelativismDocumento4 páginasWhat Is Ethical RelativismXaf FarAinda não há avaliações

- Education Is A VaccineDocumento2 páginasEducation Is A VaccineNelab HaidariAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Indian CultureDocumento16 páginasUnderstanding Indian CultureRavi Soni100% (1)

- SAMPLE ANSWERS - 3113 PortfolioDocumento7 páginasSAMPLE ANSWERS - 3113 PortfolioSam SahAinda não há avaliações

- Poemsofmalaypen 00 GreeialaDocumento136 páginasPoemsofmalaypen 00 GreeialaGula TebuAinda não há avaliações

- Kpsea Online RegslipDocumento14 páginasKpsea Online RegslipNeldia CyberAinda não há avaliações

- Grew 1999 Food and Global HistoryDocumento29 páginasGrew 1999 Food and Global HistoryKaren Souza da SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared DiamondDocumento2 páginasGuns, Germs and Steel by Jared DiamondJolens FranciscoAinda não há avaliações

- Re-Engaging The Public in The Digital Age: E-Consultation Initiatives in The Government 2.0 LandscapeDocumento10 páginasRe-Engaging The Public in The Digital Age: E-Consultation Initiatives in The Government 2.0 LandscapeShefali VirkarAinda não há avaliações

- Franklin Cemeteries Project and Preservation Plan 12.2010Documento132 páginasFranklin Cemeteries Project and Preservation Plan 12.2010brigitte_eubank5154Ainda não há avaliações

- WWW Britannica Com Topic List of Painting Techniques 2000995Documento5 páginasWWW Britannica Com Topic List of Painting Techniques 2000995memetalAinda não há avaliações

- Combination of Different Art Forms As Seen in Modern Times ESSSON 1Documento8 páginasCombination of Different Art Forms As Seen in Modern Times ESSSON 1Rolyn Rolyn80% (5)

- Lexicology I - HistoryDocumento20 páginasLexicology I - HistoryCiatloș Diana ElenaAinda não há avaliações

- Coaching Swimming Successfully Coaching SuccessfulDocumento391 páginasCoaching Swimming Successfully Coaching SuccessfulAurora Nuño100% (1)

- Personal Identity in The Musical RENTDocumento59 páginasPersonal Identity in The Musical RENTSharon Maples100% (3)

- RedbullDocumento35 páginasRedbullpritam100% (1)

- Larry Scaife JRDocumento2 páginasLarry Scaife JRapi-317518602Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan in Book Review 6Documento5 páginasLesson Plan in Book Review 6Yreech Eam100% (1)

- Writing Rubric - EIC 5 - Task 1 - Social Network ConversationDocumento2 páginasWriting Rubric - EIC 5 - Task 1 - Social Network ConversationAiko NguyênAinda não há avaliações

- Group 4 LitDocumento19 páginasGroup 4 LitDenzel Montuya100% (1)

- Caste System in IndiaDocumento23 páginasCaste System in Indiapvvrr0% (1)

- Department of Education Region V-Bicol Division of Camarines Norte Moreno Integrated School Daet Second Summative Test Creative Writing 11Documento3 páginasDepartment of Education Region V-Bicol Division of Camarines Norte Moreno Integrated School Daet Second Summative Test Creative Writing 11Jennylou PagaoAinda não há avaliações

- Flexibility and AdaptabilityDocumento2 páginasFlexibility and AdaptabilityJuan PabloAinda não há avaliações

- Meet Joe and Ana, Look How They Introduce ThemselvesDocumento3 páginasMeet Joe and Ana, Look How They Introduce ThemselvesMarcela CarvajalAinda não há avaliações

- Downloaddoc PDFDocumento11 páginasDownloaddoc PDFRaviAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison 5RU WOS SCO 2004 2013 30july2013 ChartDocumento6 páginasComparison 5RU WOS SCO 2004 2013 30july2013 ChartFreedomAinda não há avaliações

- Knezevic Clothing OsDocumento13 páginasKnezevic Clothing OsSABAPATHYAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Education in Nepal and Brain Drain PDFDocumento2 páginasMedical Education in Nepal and Brain Drain PDFbhagyanarayan chaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- Angela Gloria Manalang Literary WorksDocumento8 páginasAngela Gloria Manalang Literary WorksWendell Kim Llaneta75% (4)

- Music Advocacy PaperDocumento4 páginasMusic Advocacy Paperapi-321017455Ainda não há avaliações

- Journal Entry 4Documento3 páginasJournal Entry 4api-313328283Ainda não há avaliações

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (30)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNo EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (12)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessNo EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (86)

- The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersNo EverandThe Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Greater PhilosophersAinda não há avaliações

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYNo EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNo EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (10)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionNo EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (51)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyNo EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (7)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessNo EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (60)

- Knocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldNo EverandKnocking on Heaven's Door: How Physics and Scientific Thinking Illuminate the Universe and the Modern WorldNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (64)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosNo Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (207)

- This Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceNo EverandThis Is It: and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual ExperienceNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (94)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentNo EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (17)

- Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemNo EverandMoral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and ThemNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (115)

- The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead PhilosophersNo EverandThe Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead PhilosophersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (79)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireNo EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (59)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklNo EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (101)