Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

DRF

Enviado por

jangnoesaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DRF

Enviado por

jangnoesaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

RESEARCH

CONFLICTING PRIORITIES: EMERGENCY NURSES

PERCEIVED DISCONNECT BETWEEN PATIENT

SATISFACTION AND THE DELIVERY OF

QUALITY PATIENT CARE

Author: Mary L. Johansen, PhD, NE-BC, RN, Newark, NJwwwwww

Introduction: As hospitals compete for patients and their

healthcare dollars, the emergency nurse is being asked to

provide excellent nursing care to customers rather than

patients. This has changed the approach in delivering quality

care and has created favorable conditions for conflict as the

nurse tries to achieve specific patient satisfaction goals.

Methods: A sample of 9 emergency nurses from 2 hospitals

in northern New Jersey participated in focus groups designed

to learn about the types of conflict commonly encountered, and

to identify the attitudes and understanding of the emergency

nurses experiencing conflict and how interpersonal conflict is

dealt with.

Results: Thematic content analysis identified an overarching

theme of conflicting priorities that represented a perceived

disconnect between the priority of the ED leadership to

achieve high patient satisfaction scores and nurses priority to

urses working in the emergency department are

confronted with conflict every day. Conflict is an

inevitable part of life when one works in a fast-paced

and demanding environment. The ED environment provides

favorable conditions for conflict as the nurse navigates constant

change, people who are in extremely vulnerable emotional positions, demanding workloads, poor communication, and critical

incidents such as unexpected patient deaths.1-3 Compounding

Mary L. Johansen, Member, ENA Chapter 24, is Assistant Clinical Professor,

Rutgers University, College of Nursing, Newark, NJ.

For correspondence, write: Mary L. Johansen, PhD, NE-BC, RN, Rutgers

University, College of Nursing, Ackerson Hall, Room 324, 180 University

Avenue, Newark, NJ 07102; E-mail: mjohanse@rutgers.edu.

J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:13-9.

Available online 26 July 2012.

0099-1767/$36.00

Copyright 2014 Emergency Nurses Association. Published by Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2012.04.013

January 2014

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

provide quality care. Three interacting sub-themes were

identified: (1) staffing levels, (2) leaders dont understand, and

(3) unrealistic expectations. The study also found that

avoidance was the approach to manage conflict.

Discussion: The core conflict of conflicting priorities was

based on the emergency nurses perception that while patient

satisfaction is important, it is not necessarily an indicator of

quality of care. Interacting sub-themes reflect the way in

which conflict priorities were influenced by patient satisfaction

and the nurses ability to provide quality care. Avoidant

conflict management style was used to resolve conflicting

priorities because nurses perceive that there is not enough

time to address conflict even though it could impact on work

stress and patient care.

Key words: Conflict management; Emergency department conflict;

Patient satisfaction; Quality patient care

the problem is the requirement placed on the emergency nurse

to achieve specific patient satisfaction goals. The comparison of

hospitals on topics that are important to consumers has led to

the determination by hospitals that superior patient satisfaction

is vital to their financial success and has refocused the efforts of

the nurse to view patients as customers.4,5 This focus places an

enormous burden on emergency nurses to provide hotel service quality patient care in a smooth, holistic, and speedy manner, which is not always congruent with the ED environment

or even the patients medical needs.

Interpersonal conflict or conflict between individual

members of the health care team is the most common

source of conflict in the emergency department.6 Although

it is generally viewed as confrontational behavior, conflict

has multiple meanings. In the literature, it is defined as

inherent differences in goals, needs, desires, responsibilities,

perceptions, and ideas that are generally predictable. 7

When conflict is not resolved well, it can become problematic quickly and negative consequences can occur, such as

work stress, burnout, absenteeism, decreased productivity,

WWW.JENONLINE.ORG

13

RESEARCH/Johansen

and reduced quality of care. 8,9 These negative consequences contribute to high staff turnover that occurs at a

time when emergency nurses are needed more than ever.2,4

Although ED environments are among the most

demanding and stressful in health care,2,10 little is known

about nurses perceptions of conflicts. Managing conflicts is

among the key challenges facing the emergency nurse, and

it is in the interest of the nurse not to avoid conflict in the

emergency department but to productively manage disagreements with skilled communication. Both the American Association of Critical Care Nurses11 and The Joint Commission

(JC)10 recognize that proficiency in communication skills is

an essential element to a healthy work environment among

members of the health care team. Good communication also

improves relationships with patients and families, who are the

consumers of nursing care. A breakdown in communication

and collaboration can lead to disruptive behaviors by the

involved parties and increased patient errors.3,8,10 Handling

conflicts in an efficient and effective manner may result in

improved quality, patient safety, and staff morale and may

reduce work stress for the emergency nurse.

Although conflict is an inevitable characteristic of work

environments, it is not conflict but rather the style with

which the individual manages conflict that is important

and that directly affects worker and patient outcomes.12

Effective resolution of conflict depends on assessing the nature of the conflict and selecting the most appropriate management style for the situation. Research suggests that the

conflict management style rendered by the nurse in response

to conflict may directly affect her level of work stress and also

may affect the clinical outcomes of the patient.13-16 The aims

of this study were to: (1) learn more about the types of conflict emergency nurses are commonly encountering, (2) identify the ideas, attitudes, understanding, and thinking patterns

of the emergency nurse regarding the phenomenon of conflict, and (3) to understand how emergency nurses currently

deal with interpersonal conflict.

Method

RESEARCH DESIGN

A qualitative research design featuring focus groups composed of nurses working in the emergency department was

used in this study. Qualitative research allows the individuals

perspective of phenomena to be studied in the context in

which the event occurs, providing rich descriptions that

enable the reader to understanding the reality of the phenomenon being studied.17,18 Focus groups rather than individual

interviews were used because group interaction is thought to

be a significant attribute that helps people explore and clarify

views that are less accessible in one-on-one interviews.

14

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY NURSING

Focus groups produce insight and a rich amount of

experiential information that allows the participants to hear

and respond to diverse viewpoints.18-20 Focus group interaction may reveal more about what the emergency nurse

understands of a particular conflict and the reasoning

behind her or his conflict resolution approach.18

A focus group discussion guide was developed by the

researcher. This guide included items related to the most vexing and recurring types of conflicts that emergency nurses

encounter at work, who the conflict is most often with and

what it is about, and how the individual nurse and the organization handle such conflict. Finally, participants were asked

about training in managing conflict in the emergency department and the types of factors that might be used to measure

whether the training was effective in helping the emergency

department do its job better or more successfully.

RESEARCH SETTING

The nurse participants were recruited from 2 acute care

facilities located in Northern New Jersey. One focus

group was held in a private conference room at each organization where the staffs are employed. The date, time,

and location of the room were disclosed only to focus

group nurse participants.

RESEARCH PROCEDURE

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Strict adherence to the requirements for the protection of human subjects

were followed, and the investigator completed the human subjects training and followed the policies and procedures related

to safe and ethical practices, confidentiality, and informed consent. Loss of confidentiality and emotional discomfort were

potential risks when describing experiences. Precautions were

taken to minimize these risks by thoroughly explaining the

study, using a trained moderator, and emphasizing that participation was voluntary. The nurses were asked to sign an

informed consent document before the start of the session

and were informed that they could choose to withdraw at

any time and/or choose not to answer any questions that made

them uncomfortable. Because the intent of this study was to

understand how nurses think and talk about a particular topic,

purposive sampling rather than random sampling was used to

select the focus group participants.18,19

The chief nursing officer and the nursing leadership

of the 2 acute care facilities assisted in providing access to

the emergency nurses. The principal investigator (PI)

recruited nurses from each emergency department who

met the inclusion criteria, that is, being currently

employed as a professional registered nurse in a hospital-based emergency department in the United States

and being a direct patient care provider. Contact was

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

January 2014

Johansen/RESEARCH

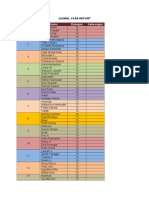

TABLE 1

TABLE 2

Demographic characteristics of the sample

Variable

Gender

Male

Female

Race

African American/black

Alaskan Native or

American Indian

Asian

Hispanic

Pacific Islander

Caucasian/white

Mixed race

Highest nursing degree

Diploma

Associate degree

Baccalaureate degree

Masters degree

Magnet

Yes

No

Board certification in

emergency nursing

Yes

No

Conflict resolution training

Yes

No

Current position

Staff nurse

Charge nurse

Team leader/shift coordinator

Descriptive data for the sample

1

8

10

90

0

0

0

0

1

0

1

8

0

0

0

10

90

0

2

2

3

2

22

22

33

22

6

3

67

33

1

8

10

90

5

4

56

44

8

0

1

90

0

10

made through an E-mail invitation that explained the

purpose of the study, the consent for participation, and

an explanation of how the rights of the nurse would be

protected. Nurses who were interested in the study were

asked to respond to the E-mail invitation and subsequently were contacted by the PI. Only the selected individuals had access to this information.

SAMPLE

Nine nurses participated in 2 focus groups. The majority of

the nurses were white women (n = 8) who were employed

full time as staff nurses and were not board certified in

January 2014

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

Variable

Mean

SD

Range

Age (y)

Years of nursing

experience

Years of ED nursing

experience

Years worked in current

position

37.3

16.88

11.98

16.09

23-59 y

2-42 y

11.77

10.88

2-31 y

9.1

9.83

6 mo-26 y

emergency nursing. Two thirds of the nurses worked in

facilities designated as magnet hospitals, and almost 25%

had received some type of formal training in conflict resolution. More than half of the nurses were baccalaureate prepared (Table 1).

The mean age of the nurses was 37.3 years (SD,

11.98). One third of the nurses had 30 years or more of

experience (n = 3), whereas the remaining two thirds had

2 to 13 years experience (n = 6). Two thirds of the nurses

had less than 7 years experience (n = 6), and the remaining third had 20 to 31 years of ED experience (n = 3)

and had worked in their present position for more than

1 year. Descriptive data for the sample are presented in

Table 2.

DATA COLLECTION

Nurse participants meeting the inclusion criteria were

divided into two groups with 4 to 5 nurses per group. Each

focus group session was digitally recorded to capture accurate data for typed verbatim transcripts. The PI and focus

group nurse participants sat around a table to facilitate the

discussion. A demographic questionnaire was distributed

to the group. The PI followed a focus group guide while

conducting each session. The focus group sessions lasted

30 to 45 minutes.

DATA ANALYSIS

The focus group recorded session was transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy through careful review(s)

by the PI, who read the transcript while listening to

the digital recording. Although transcript-based analysis

is time consuming, it is the most rigorous way of drawing out key comments.19

Thematic content analysis was used to analyze focus

group data. A list of common themes was extracted from

the texts by the researcher to give expression to the communality of voices across participants.20 The transcribed

text was read as a whole first and then uploaded into

WWW.JENONLINE.ORG

15

RESEARCH/Johansen

Atlas-Ti to facilitate analysis. Codes were generated

through careful readings from the transcripts by the PI.

Codes were reviewed and collapsed into a coding template

that then was used to consistently label data segments that

contained similar material.18-20 The Atlas-ti computer software program was used to organize the coded segments and

relate them to a particular theme or sub-theme. Analysis of

the themes was conducted to enable the PI to answer the

research questions: (1) What types of conflicts are commonly encountered? (2) What are the ideas, attitudes,

understanding and thinking patterns of the emergency

nurse experiencing a conflict? and (3) How do emergency

nurses currently deal with interpersonal conflict?

Results

The results identified insightful information regarding the

conflicts emergency nurses are encountering and how they

currently deal with them. In general, the nurse participants

defined conflict as a disagreement that interfered with the

delivery of patient care and was associated with negative

emotional reactions. During the nurses discussion of their

experience of conflict in the ED workplace, an overarching

theme emerged, conflicting priorities, that could have an

impact on their work stress and patient care. The ED leadership priority was perceived to be achieving high patient

satisfaction scores, whereas the priority for the emergency

nurses was to provide quality care. This core conflict was

based on the emergency nurses perception that although

patient satisfaction is important, it is not necessarily an

indicator of quality of care. When speaking about patient

satisfaction, one nurse explained,

That makes us feel like we are servants, maybe like waitresses,

or I dont knowI mean, we do serve the population and we

are supposed to do that, but I (ah) its kind of demeaning,

actually, I think cause we are all doing a good job and we are

working as fast as we can and do the best quality we can for

everybody, but its never enough!

This overarching theme of conflicting priorities

encompassed 3 interacting sub-themes:

1. Staffing levels

2. Leaders dont understand

3. Unrealistic expectations

STAFFING LEVELS

Conflict with staffing levels and patient flow was a leading

issue of distress for the nurse participants. The doors to the

emergency department never close. Patient flow is contin-

16

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY NURSING

uous but with peaks of patient volume throughout the day.

Although established staffing patterns guide the safe assignment of patients to nurses, any drastic fluctuation in census

or patient acuity can affect the nurse-to-patient ratio. This

situation provides a significant source of frustration for the

nurses and illustrates the conflict priorities. One nurse stated, You are going to be overwhelmed with the number of

people you are going to get.

This sentiment was echoed by other nurses, who perceived that the driving force behind patient throughput

from triage to the main emergency department was

patient satisfaction:

If you are staffed for 40 (patients) and you have 40 patients in

your ED but you have another 20 in your waiting room,

those 20 are coming back. Who is increasing that ratio?

We are constantly pushed to the edge that these patients need

to come back, and thats a safety issue.

Managers want the ER to run efficiently with whatever

staffing is there. Patient satisfaction is what they are concerned with.

In these situations, conflict arose between the nurse

and the charge nurse. For example, one participant noted,

The charge nurse is pressuring [us] to bring those patients

back. Why is the charge nurse continuing to bring us these

patients that nobody wants?

The participants also placed a strong emphasis on patient

acuity and its contributory role in staffing level conflict. One

nurse described the fragile relationship between patient

assignments, acuity, stress, and conflict: You may be getting

your sixth patient and another nurse may have 2, but she may

be on a one to one with those 2 patients, and you have no

knowledge so you are building up hostility.

Several nurses pointed out that there is a double standard when it comes to staffing levels in the emergency

department and the rest of the hospital. This double standard also was a frequent source of distress and frustration.

A host of comments illustrated this point:

With high acuity throughout the institution, you have a ratio of 1 to 1 or 1 to 2 and in the ED you dont have any

dynamic of ratios. You can have 3 critically ill patients and

3 other patients.

It doesnt matter how many ICU patients you have, you

just repeatedly keep getting the ICU just because its your

turn, it doesnt matter what the acuity is.

I dont understand how within an institution you can

have a state directive that you have to have 1 nurse to

2 patients in this setting but a couple of floors down

that doesnt apply at all. There is something very wrong

with that.

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

January 2014

Johansen/RESEARCH

LEADERS DONT UNDERSTAND

Conflicts with the ED leadership team/management

were described in detail by the participants. Nurses

observed that managers look at the computer screen

and count numbers.

Participants shared comments such as There is really

no consideration for the staff because its the patients who

are bringing in the scores that are bringing in everything

else that runs the hospital and I think the safety issue

is overlooked sometimes by management because our

(hospital) goal is patient satisfaction.

The nurses perceived a generalized lack of support

when patient volume and acuity were exceeding the

immediate available resources: You can have three critically ill patients and three other patients and management

doesnt step in and provide backup in the sense of dividing

up the assignments, pulling more staff.

Further, nurses indicated that after the volume and acuity diminish, the nurses are left to answer for all of the care

that was rendered as well as the care that was not rendered:

It becomes a very dangerous situation and its kinda because the environment is so hectic its overlooked until

it calms down and then youre asked to answer for things

that you had no awareness of. That level of stress for anyone who works in the ER is a very important dynamic and

I think throughout the United States its something thats

not looked at.

UNREALISTIC EXPECTATIONS

An important issue that emerged in the thematic analysis

was meeting what nurses perceived as unrealistic expectations of the organization. In an attempt to drive up patient

satisfaction scores, many hospitals are implementing programs to decrease overall waiting times and, more specifically, times to be seen by a physician. The nurses refer to

these time requirements as unreasonable because they create unrealistic expectations among patients of when they

are going to be seen, creating conflict between the nurse

and the patient: For the most part they [patients] expect

to be seen NOW and they expect to be seen immediately

by the doctor. One nurse shared, Ive had somebody

from this ER call 911 in 8 minutes because they [the

patient] werent seen quick enough and wanted to be

transferred to another hospital.

These target times also have created conflict between

the nurse and the physician because physicians likewise

are being held to a strict time requirement:

There is your conflict because you are giving a nurse who

has three critical care patients more patients but yet your

January 2014

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

process is designed to have a patient seen by a doctor within 20 minutes of arrival and the thing is that nobody wants

to take responsibility.

Nurses relating to this comment also added:

One doctor would expect you to take their patient before another doctor. They dont like to be put second to

each other. When physicians come at you, that they want

their patients to take priority.

The charge nurse is also caught in this time conflict

with the nurse and the management: Because the charge

nurse is pressuring to bring those patients back because she

has to respond to our director or whoever else who said,

Why are these people leaving?

DEALING WITH CONFLICT

To answer the final question, nurses were asked about how

they dealt with conflict. The predominant approach used by

the emergency nurse participants to resolve these conflicts

was avoidance. The style was chosen because it provided

minimal interruption. Numerous comments described the

frustrations experienced by the nurse:

Its not a matter that you dont deal with though, and you

dont have the time to deal with it. Your focus is on patient

care and that is what you set as your priority and you

manage it the best way you can.

So many patients and you have so many things to do and

you are so busy you just dont even have time to say anything, you just know that whats best for the patient you

have to care of the patient and just move on.

Discussion

The overarching theme identified by focus group participants was conflicting priorities that represented a perceived

disconnect between a focus on patient satisfaction and the

delivery of quality patient care. The nurses perceived that

the priority of the ED and hospital leadership was patient

satisfaction, whereas nurses priority was to provide quality

care. This perceived disconnect may lie in the conceptual

understanding of what constitutes quality care. The quality

of care in the emergency department has not been

addressed in the empirical literature. Established National

Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) indicators were developed primarily for inpatients. Now is the

time to validate NDNQI measures that are appropriate

in the emergency department and develop specific ones

for this setting.

The NDNQI5 provides operational definitions for

nurse-sensitive acute quality care indicators, which include

WWW.JENONLINE.ORG

17

RESEARCH/Johansen

pressure ulcers, falls, nosocomial infections, and patient

satisfaction as it relates to pain management, patient education, overall care, and nursing care. The ambulatory environment of the emergency department differs from that of

an inpatient setting. The mandatory elements of care

defined by regulatory bodies, expanding technologies for

documentation and care delivery, and frequent change present a complex maze of practice challenges for the ED

nurse, suggesting that there might be difference in how

quality of care should be defined and measured in the

emergency department. In this study, the nurses perception of quality of care was globally described as, taking care of those patients as you really want to take care

of them. Defining what quality of care means to the ED

nurse broadens our understanding of how quality should

be measured. This is an important first step toward

developing nurse-sensitive quality indicators that are

valid, reliable, and relevant to the emergency department.

As hospitals compete for patients and their health care

dollars, the emergency nurse is being asked to provide

excellent nursing care to customers rather than patients.

This situation is attributable in part to the fact that hospitals rely on patient satisfaction and Hospital Consumer

Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores to

measure their effectiveness in delivering health care services.21 This disconnect to deliver hotel services that

patients can appreciate rather than quality clinical care that

may not be tangible gave the nurses in this study the

impression that their contribution was not valued.

The sub-themes reflected the way that conflicting priorities affected nurses perceptions of their ability to provide

quality care. The use of patient satisfaction as the tool

employed to measure and evaluate how hospital expectations and goals are met placed pressure upon the relationships between nurses and patients, nurses and physicians,

nurses and charge nurses, and nurses and management.

The emergency nurses in this study reported feeling frustrated and powerless because management did not listen

to their issues of concern regarding unrealistic expectations

of overall waiting times and when patients are going to be

seen by a physician. Although appropriate staffing ratios in

the emergency department has been a conundrum for leadership/ management, participants verbalized a generalized

lack of support when patient volume and acuity exceeded

the immediate available resources.

Findings from this study reflect many of the conflict

issues that were identified in a recent survey of nurses conducted by the Center for American Nurses that examined

the nurses perception of conflict in the workplace. Respondents (n = 858) identified the need for effective leadership

to resolve conflict. The JC10 suggests that a proactive way

18

JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY NURSING

of addressing conflict issues, working through them, and

moving toward resolution supportive environment may

be achieved through collaborative practice and inter-professional dialogues across disciplines. This study shows that

ED leadership expectations affect both nurses and physician relationships and may have an effect on collaborative

practice in emergency departments.

Another major finding in this study is the perception

of the emergency nurse that there is not enough time to

address conflict even though it could have an impact on

work stress and patient care. Research has established that

the use of an avoidant conflict management style, as

demonstrated by the focus group participants, is related

to higher levels of work stress.13-15 This strategy prevents

the root problem from being addressed, and thus the conflict may persist. The JC10 has expressed concern about

this avoidance behavior because it can lead to very poor

communication, which certainly leads to poor patient

outcomes. It also can lead to a higher level of stress in

the nurse.

LIMITATIONS

The study findings are limited in terms of generalization.

This study was limited to only 2 emergency departments

from Northern New Jersey. Nevertheless, the data from

this study can provide insight into the nature of conflict

as defined as disagreements experienced by emergency

nurses, which can be applied to other ED settings that have

contextual similarities to those in which the data were collected.20 The sizes of the focus groups were not ideal.

However, the data attained was nevertheless rich and

meaningful. An additional limitation was the use of focus

groups rather than individual interviews, which has the

potential for peers to affect or limit the discussion and

the worthwhile information obtained.18-20

IMPLICATIONS FOR EMERGENCY NURSES

Emergency nurses need to be proactive about ensuring that

their contributions to patient care are measured.22 A collaborative effort by the ED leadership and nurses is needed to

ensure that nurse-sensitive quality indicators are included in

reports of hospital quality.4 To make this effort work, the

nurses and ED leaders first must agree on operational definitions of patient satisfaction and quality care. Data collection

instruments must include nurse-sensitive indicators that

measure the concepts of both patient satisfaction and quality

care.21 Quality indicators may include acute care NDNQI

measures such as falls and patient satisfaction as it relates

to pain management, patient education, nursing care, and

overall care. Examples of potential indicators appropriate

for the ED include triage quality (assessment and duration)

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

January 2014

Johansen/RESEARCH

and nurse activity (ongoing direct assessment and intervention). Quality indicators that are perceived as important by

ED nurses need to be developed and tested.

Demonstrating concern and providing a rationale for

decisions that affect the staff nurse go a long way to highlighting the importance of constructive relationships that

can effectively manage conflict.4 The ED leadership needs

to actively listen, develop structures to facilitate this collaborative process of resolving identified issues, and provide a

rationale for decisions as appropriate.2,10,23,24

Conclusion

Changes in health care delivery have required emergency

departments to reevaluate how they are delivering patient

care. Health care administrators have recognized that fiscal

viability is linked to patient satisfaction.21 Their efforts to

view patients as customers have changed the way nurses

approach the delivery of quality care and has created favorable conditions for conflict as the nurse tries to achieve specific patient satisfaction goals, such as reduced wait times,

while providing quality care. Findings from these focus

groups suggest that the emergency nurses perceptions of

the importance of patient satisfaction and quality of care

differ from those of patients and ED/hospital leadership.

This mismatch influences the nurses perception of leaders

understanding and the support from leadership/management in their approach to resolving staffing issues and organizational expectations. The important first step toward

developing nurse-sensitive quality indicators is defining

what patient satisfaction and quality of care means to the

ED nurse. ED leadership needs to recognize that conflicting priorities is not only a staff issue but an organizational

issue as well, because poor communication provides a work

environment that lends itself to conflict and stress.

REFERENCES

1. Emergency Nurses Association. Violence in the emergency department.

http://www.ena.org/government/Advocacy/Violence/Pages/Default.

aspx. Accessed November 30, 2011.

2. Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2006. Hospital-based emergency care:

at the breaking point. http://www.iom.edu/CMS/3809/16107/35007.

Accessed November 30, 2011.

3. Oster NS, Doyle CJ. Critical incident stress and challenges for the

emergency workplace. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:339-413.

4. Dougherty C. Customer service in the emergency department. Top

Emerg Med. 2005;27:265-72.

January 2014

VOLUME 40 ISSUE 1

5. The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators. https://www.

nursingquality.org/. Accessed April 26, 2012.

6. Cox KB. The effects of unit morale and interpersonal relations on conflict in the nursing unit. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:17-25.

7. Almost J. Conflict within nursing work environments: concept analysis.

J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:444-54.

8. Aiken L, Kanai-Pak M, Sloane D, Poghosyan L. Poor work environment

and nurse inexperience are associated with burnout, job dissatisfaction

and quality deficits in Japanese hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:3324-9.

9. Shader K, Broome M, Broome C, West M, Nash M. Factors influencing

satisfaction and anticipated turnover for nurses in an academic medical

center. J Nurs Adm. 2001;31:210-6.

10. Joint Commission. Sentinel event alert: behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/Sentinel

EventAlert/. Published 2006. Accessed November 1, 2011.

11. American Association of Critical Care Nurses. Standards for establishing

and sustaining healthy work environments: a journey to excellence.

http://www.aacn.org/WD/HWE/Docs/HWEStandards.pdf. Accessed

April 26, 2012.

12. Laschinger H, Purdy N, Cho J, Almost J. Antecedents and consequences

of nurse managers perceptions of organizational support. Nurs Econ.

2006;24:20-7.

13. Friedman R, Tidd S, Currall S, Tsai J. What goes around comes around:

the impact of personal conflict style on work conflict and stress. Int J

Confl Manage. 2000;11:32-55.

14. Montoro-Rodriguez J, Small J. The role of conflict resolution styles

on nursing staff morale, burnout and job satisfaction in long-term

care. J Aging Health. 2006;18:385-406.

15. Sportsman S, Hamilton P. Conflict management styles in the health

professions. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23:157-66.

16. Vivar CG. Putting conflict management into practice: a nursing case

study. J Nurs Manage. 2006;14:201-6.

17. Parahoo K. Nursing Research: Principles, Process and Issues. London: Macmillan; 1997.

18. Plummer-DAmato P. Focus group methodology part 2: considerations

for analysis. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2008;15:123-8.

19. Krueger RA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000.

20. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative

Research. 1st ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2007.

21. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. HCAHPS: patients perspectives of care survey. https://www.

cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/30-HospitalHCAHPS.asp. Accessed

November 3, 2011.

22. Yellen E. The influence of nurse-sensitive variables on patient satisfaction [research]. AORN J. 2003;2(783-788):790-3.

23. Friesen MA, DeWitty V, Osborne J, Rosenkranz A. Nurses perceptions

of conflict in the workplace: results of the Center for American Nurses.

Nurs First Online J. 2009;2:12-6.

24. Gerardi D. Using mediation techniques to manage conflict and create

healthy work environments. AACN Clin Issues. 2004;15:182-95.

WWW.JENONLINE.ORG

19

Você também pode gostar

- Jadwal Case ReportDocumento3 páginasJadwal Case ReportjangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Confounding Variable Is Information. This Research Employs A Close QuestionnaireDocumento1 páginaConfounding Variable Is Information. This Research Employs A Close QuestionnairejangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Self-Assessment or Self Deception? A Lack of Association Between Nursing Students' Self-Assessment and PerformanceDocumento9 páginasSelf-Assessment or Self Deception? A Lack of Association Between Nursing Students' Self-Assessment and PerformancejangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- Jadwal Kuliah Farmakologi SPDocumento1 páginaJadwal Kuliah Farmakologi SPjangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Dapus Acak2Documento1 páginaDapus Acak2jangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- Metlit Bab IIDocumento20 páginasMetlit Bab IIjangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Variables and An Operational DefinitionDocumento39 páginasVariables and An Operational DefinitionjangnoesaAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Cdd161304-Manual Craftsman LT 1500Documento40 páginasCdd161304-Manual Craftsman LT 1500franklin antonio RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Achievement Test Science 4 Regular ClassDocumento9 páginasAchievement Test Science 4 Regular ClassJassim MagallanesAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Rekapan Belanja JKNDocumento5 páginasRekapan Belanja JKNAPOTEK PUSKESMAS MALEBERAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- EdExcel A Level Chemistry Unit 4 Mark Scheme Results Paper 1 Jun 2005Documento10 páginasEdExcel A Level Chemistry Unit 4 Mark Scheme Results Paper 1 Jun 2005MashiatUddinAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Esomeprazol Vs RabeprazolDocumento7 páginasEsomeprazol Vs RabeprazolpabloAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- 742210V01Documento2 páginas742210V01hakim_zadehAinda não há avaliações

- 03 - Air Ticket Request & Claim Form 2018Documento1 página03 - Air Ticket Request & Claim Form 2018Danny SolvanAinda não há avaliações

- ARI 700 StandardDocumento19 páginasARI 700 StandardMarcos Antonio MoraesAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Well Being Journal December 2018 PDFDocumento52 páginasWell Being Journal December 2018 PDFnetent00100% (1)

- ICT ContactCenterServices 9 Q1 LAS3 FINALDocumento10 páginasICT ContactCenterServices 9 Q1 LAS3 FINALRomnia Grace DivinagraciaAinda não há avaliações

- R. Raghunandanan - 6Documento48 páginasR. Raghunandanan - 6fitrohtin hidayatiAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- GEC PE 3 ModuleDocumento72 páginasGEC PE 3 ModuleMercy Anne EcatAinda não há avaliações

- PED16 Foundation of Inclusive Special EducationDocumento56 páginasPED16 Foundation of Inclusive Special EducationCHARESS MARSAMOLO TIZONAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Thornburg Letter of RecDocumento1 páginaThornburg Letter of Recapi-511764033Ainda não há avaliações

- JIDMR SCOPUS Ke 4 Anwar MallongiDocumento4 páginasJIDMR SCOPUS Ke 4 Anwar Mallongiadhe yuniarAinda não há avaliações

- AD Oracle ManualDocumento18 páginasAD Oracle ManualAlexandru Octavian Popîrțac100% (2)

- Guia Laboratorio Refrigeración-2020Documento84 páginasGuia Laboratorio Refrigeración-2020soniaAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- 134.4902.06 - DM4170 - DatasheetDocumento7 páginas134.4902.06 - DM4170 - DatasheetVinicius MollAinda não há avaliações

- RX Gnatus ManualDocumento44 páginasRX Gnatus ManualJuancho VargasAinda não há avaliações

- Zemoso - PM AssignmentDocumento3 páginasZemoso - PM AssignmentTushar Basakhtre (HBK)Ainda não há avaliações

- Man Wah Ranked As Top 10 Furniture Sources For U.S. MarketDocumento2 páginasMan Wah Ranked As Top 10 Furniture Sources For U.S. MarketWeR1 Consultants Pte LtdAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledapi-236961637Ainda não há avaliações

- Cardiovascular SystemDocumento47 páginasCardiovascular SystemAtnasiya GadisaAinda não há avaliações

- Biomedical EngineeringDocumento5 páginasBiomedical EngineeringFranch Maverick Arellano Lorilla100% (1)

- Tool 10 Template Working Papers Cover SheetDocumento4 páginasTool 10 Template Working Papers Cover Sheet14. Đỗ Kiến Minh 6/5Ainda não há avaliações

- Functional Capacity Evaluation: Occupational Therapy's Role inDocumento2 páginasFunctional Capacity Evaluation: Occupational Therapy's Role inramesh babu100% (1)

- A Walk in The Physical - Christian SundbergDocumento282 páginasA Walk in The Physical - Christian SundbergKatie MhAinda não há avaliações

- Apport D Un Fonds de Commerce en SocieteDocumento28 páginasApport D Un Fonds de Commerce en SocieteJezebethAinda não há avaliações

- Linkage 2 Lab ReportDocumento25 páginasLinkage 2 Lab Reportapi-25176084883% (6)

- Food DirectoryDocumento20 páginasFood Directoryyugam kakaAinda não há avaliações