Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Sust Dev Ethics of Our Common Future IPSR 1999 ZN

Enviado por

Yan RustanDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Sust Dev Ethics of Our Common Future IPSR 1999 ZN

Enviado por

Yan RustanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Political Science Review (1999), Vol. 20, No.

2, 129149

Sustainable Development: Exploring the

Ethics of Our Common Future

OLUF LANGHELLE

ABSTRACT. The concept of sustainable development was placed on the

international agenda with the release of the report Our Common Future by

the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987.

Although considerable attention has since been devoted to the idea of

sustainable development itself, the broader conceptual framework of the

ideawhereby the Commission tried to integrate environmental policies

and development strategies in order to create the foundation for a global

partnershiphas been neglected in much of the literature. The purpose

of the present article is to offer an interpretation of Our Common Future,

where the concept of sustainable development is linked to the broader

framework of normative preconditions and empirical assumptions. The

structure of the argument is to demonstrate that the relationship between

sustainable development and economic growth has been over-emphasized,

and that other vital aspects of the normative framework have been

neglected. Social justice (both within and between generations), humanistic solidarity, a concern for the worlds poor, and respect for the ecological limits to global development, constitute other aspects of sustainable

development; aspects which are indeed relevant for the growing disparity

between North and South.

Introduction

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED)

published its report Our Common Future. Since then, the number of different

meanings and interpretations of the concept of sustainable development has

more or less exploded. Numerous treatments have been highly critical of Our

Common Future; the report has been seen as both ambiguous and contradictory

and incapable of specifying the mechanisms and changes necessary to realize

sustainable development.

0192-5121 (1999/04) 20:2, 129149; 006977 1999 International Political Science Association

SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi)

130

International Political Science Review 20(2)

These claims are often related to the view that Our Common Future is biased

toward economic growth. In a straightforward sense this is undoubtedly true. The

report clearly proclaims the possibility for a new era of economic growth (WCED,

1987: 1). But what kind of economic growth does the Commission actually

prescribe? What type of growth is seen as compatible with sustainable development?

The answer to this question is, I believe, equally clear: The world must quickly

design strategies that will allow nations to move from their present, often destructive, processes of growth and development onto sustainable development paths

(WCED: 49). The key question thus emerges: What kind of changespolitical and

societalfollow from the concept of sustainable development?

Interpretation, according to Charles Taylor (1985), is an attempt to make clear,

to make sense of an object of study. Interpretation aims to bring to light an underlying coherence or sense in a text which is in some ways confused, incomplete,

cloudy, or seemingly contradictory (Taylor, 1985). While many have argued that

Our Common Future contains these features, few have actually tried to give an interpretation in the above sense of the document. Instead, the report has been firmly

placed within the limits-to-growth debate which dominated the environmental

discourse prior to the Commissions report.

The domination of the issue of compatibility between sustainable development

and economic growth, however, has led to the neglect of the broader framework of

sustainable development within which the Commission attempted to integrate

environmental policies and developmental strategies. The purpose of the present

article is to argue that much of the vital meaning (and distinctness) of the sustainable development ideas has been glossed over due to a combined overemphasis and

misinterpretation of the growth issue. While the relationship between sustainable

development and economic growth is an important part of the message in Our

Common Future, it is definitely not the entire message. The aim of the present article,

therefore, is to show that Our Common Future is more coherent and potentially more

radical than either adherents or critics seem to be aware of.

The World Commission argued that although interpretations of sustainability will

vary between countries, these interpretations must share certain general features

and must flow from a consensus on the basic concept of sustainable development and

on a broad strategic framework for achieving it (WCED: 43). This article addresses

these general features. How is the basic concept to be understood? What is the

broad strategic framework for achieving sustainable development? These issues will

be treated within the same approach applied by Verburg and Wiegel, that is, there

is much to be gained in terms of clarification by elaborating concepts and their possible connections with respect to the conceptual and normative preconditions and the

implicit interrelations which shape the framework (Verburg and Wiegel, 1997).

Placing the Brundtland Commission Report in Context

One starting point, or frame of reference, for understanding Our Common Future is

to look at the remit for the World Commission on Environment and Development.

The task given the Commission by the United Nations General Assembly was to

formulate A Global Agenda for Change (WCED: ix). This is described in Brundtlands foreword as an urgent call by the General Assembly, the call consisting

of several sub-tasks.

First, to propose long term environmental strategies for achieving sustainable

development by the year 2000 and beyond.

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

131

Second, to recommend ways in which concern for the environment may be translated into greater co-operation among developing countries and between countries

at different stages of economic and social development and lead to the achievement

of common and mutually supportive objectives that take account of the interrelationship between people, resources, environment, and development.

Third, to consider ways and means by which the international community can

deal more effectively with environmental concerns.

Fourth, to help define shared perceptions of long-term environmental issues and

the appropriate efforts needed to deal successfully with the problems of protecting

and enhancing the environment, a long term agenda for action during the coming

decades, and aspirational goals for the world community (WCED: ix).

This frame of reference is important in many ways for an understanding of Our

Common Future. The mandate provides, so to speak, an initial outline. It covers the

questions the Commission is supposed to answer (find strategies, encourage cooperation, define shared perceptions and aspirational goals for the world community); the (initial) understanding or perception of what the problem is (lack of

effective strategies, lack of co-operation, none or too few shared perceptions and

aspirational goals); and finally, a meta-perspective for evaluating the report itself

(does it deliver the goods?).

Moreover, the mandate itself is open to interpretation. Even though the mandate

was formulated in terms of sustainable development, it was, at the time, not in

any way clear what was meant by the term. It had been used only in a few

documents and academic books previously, but no authoritative definition existed

at the time. (For different views on the concepts origin, see Worster, 1993; ORiordan, 1993; McManus, 1996; Jacob, 1996; and Murcott 1997.) This partly explains

the weight the report lays on defining sustainable development. Even more important, however, is the fact that the Commission perceived a degree of semantic

freedom it otherwise would not have had. Even though environmental concerns and

issues figure strongly in the mandate, some clearly wanted environmental issues to

figure even more strongly than they did. Brundtlands response here is important

for both the meaning of sustainable development and for an understanding of how

the Commission interpreted the mandate itself:

When the terms of reference of our Commission were originally being discussed

in 1982, there were those who wanted its considerations to be limited to

environmental issues only. This would have been a grave mistake. The environment does not exist as a sphere separate from human actions, ambitions, and

needs, and attempts to defend it in isolation from human concerns have given

the very word environment a connotation of naivet in some political circles

(WCED: xi).

Brundtland has later explained this aspect of the Commissions work as a way of

catching, and taking seriously, the growing skepticism in developing countries

toward the environmental concerns of the West. Commission member, Sonny

Ramphal, is portrayed as a major advocate of this view, claiming (according to

Brundtland, 1997: 78) that environmentalists are more concerned about panda

bears than human beings, and more concerned about increasing the number of

bicycles in the Third World rather than that we should acquire trucks. This orientation obviously contributed to a more development-oriented approach within the

Commission, leading a number of commentators to portray the report as strongly

anthropocentric (Adams, 1990; Kirkby, OKeefe, and Timberlake, 1995; Lafferty

132

International Political Science Review 20(2)

and Langhelle, 1995; Reid, 1995). The report states, for example, that our message

is [first and foremost] directed towards people, whose well-being is the ultimate

goal of all environment and development policies (WCED: xiv).

Another way of understanding this orientation is to see it as a reaction to the

criticism raised against the earlier World Conservation Strategy (WCS) from 1980

(IUCN/UNEP/WWF, 1980). This reportone of the first to make use of the words

sustainable developmentwas prepared by the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and published with support from the World Wildlife

Fund (WWF) and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). The WCS report

argued from a dominantly conservationist-environmentalist standpoint (Adams,

1990; Kirkby, OKeefe, and Timberlake, 1995), and was criticized for having an

anti-poverty profile. The conduct of poor people was identified as a principal cause

of environmental damage, without, however, considering poverty itself as an

integral part of the environment-and-development problem (Soussan, 1992). The

fact that the IUCN report (in its Introduction) explicitly called for a strategy to

overcome poverty, was not enough to prevent the impression that the report was

heavily dominated by environmentalist concerns. In this connection, the Brundtland

report represents a specifically different mix and ordering of environment-anddevelopment components. As later described by Brundtland: The term sustainable

development had already been used in certain contexts before the Commission was

established. What the Commission did, was to give this term a new contenta far

more political content (Brundtland, 1997: 79).

Sustainable Development: The Basic Concept

The implications of the change in questionthat is, a broadening of the concept

of sustainable developmentare most easily seen when contrasted with other

usages of the term sustainable. The term itself is derived from the Latin sus tenere,

meaning to uphold (Redclift, 1993), which does not, of course, imply any specific

normative content. Dixon and Fallon (1989) provide a basis for further clarification

by identifying three types of usage: (1) As a purely physical concept for a single resource:

Here the scope of sustainability is limited to particular renewable resources considered in isolation, with sustainability simply implying a usage no greater than the

annual increase in the resource, without reducing the physical stock. Maximum

sustainable yield, maximum sustainable cut, and so forth, are examples of the

underlying logic of this approach. (2) As a physical concept for a group of resources, or an

ecosystem: With this usage, explicit attention is devoted to different aspects of the

ecosystem. For example, forestry managed in accordance with maximum sustainable cut may create problems with increased soil erosion, changes in water yield,

wildlife habitat and species diversity. As a result of system interaction, what may

be considered as a sustainable usage of a single resource may actually be found to

be unsustainable within the context of the entire system. (3) As a socio-economicphysical concept: Here the goal is not a sustained level of a physical stock or the physical production of a given ecosystem, but an unspecified sustained increase in the

level of societal and individual welfare (Dixon and Fallon, 1989: 6), or, more

directly in accord with the language of Our Common Future, a sustained level of need

satisfaction. This third type is the usage developed by Our Common Future.

In this last context, the standard definition of sustainable development from Our

Common Future is that it is development that meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED:

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

133

43). It is this definition which is nearly universally cited in commentary on the

report, both critical and supportive. What such citations often fail to mention,

however, is that the core definition is immediately qualified by the following:

It [sustainable development] contains within it two key concepts:

the concept of needs, in particular the essential needs of the worlds poor,

to which overriding priority should be given; and

the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environments ability to meet present and future needs (WCED: 43).

We shall address the definition and its key concepts in turn. While the first part

of the definition addresses the importance of meeting present human needs, the

second part, according to Reid (1995), seems to strike two chords. The first touches

on our sense of guilt for what we have done to the planet; while the second

relates to a very deeply-rooted human desire to make sure our childrens futures

are provided for (Reid, 1995: xvi). While one may wish to quibble with the implied

atonement of Reids first claimhave we, in fact, intentionally harmed the

planet?there seems little doubt that the definition rests on the prospect that we

are, in fact, capable of damaging the sustaining capacity of the planet for future

generations. It is the presence of an actual, or at least potential, inter-temporal

conflict of interest here which partly shapes the definition of sustainable development.

Moreover, the satisfaction of human needs is seen as the major objective of development (WCED: 43). This may be called the goal of development (Malnes, 1990: 3). The

qualification that this development also must be sustainable is a constraint placed

on this goal, meaning that each generation is permitted to pursue its interests only

in ways that do not undermine the ability of future generations to meet their own

needs. This may be called the proviso of sustainability (Malnes, 1990: 3). Since the

sustainability constraint is a necessary condition for future need satisfaction, which

is part of what sustainable development is supposed to secure, the proviso of

sustainability becomes a necessary part of the goal of development, thus providing

the inter-dependency of the concept. Or, as Malnes formulates it, the proviso is

entailed by the very goal whose pursuit it constrains (Malnes, 1990:7).

Some Key Implications of the Concept

The above framework and understanding of sustainable development has some farreaching consequences for an understanding of the ideas which are often neglected.

First of all, there are a number of threats, in addition to environmental

problems, which could compromise the ability of future generations to meet their

own needs. In fact, Our Common Future identifies potential political, social, economic,

technological and cultural constraints on future development. The most obvious

example is the threat of a global nuclear war. The sustainability proviso is thus not

only about environmental sustainability, although many prefer to restrict the term

to this usage (Meadowcroft, 1996). One example is the definition given in the report

Caring for the Earth (which was the follow-up to the first World Conservation Strategy).

Here sustainable development is defined as improving the quality of human life

while living within the carrying capacity of supporting ecosystems (IUCN/UNEP/WWF,

1991: 10). In one sense, this implies a more precise definition, but in another, it

represents an unqualified limitation which obviously excludes many other possible

threats to future development.

134

International Political Science Review 20(2)

But the concern for the environment nonetheless constitutes a central part of the

proviso of sustainability also in Our Common Future. This is formulated as a minimum

requirement for sustainable development, and is also referred to as physical

sustainability: At a minimum, sustainable development must not endanger the

natural systems that support life on Earth: the atmosphere, the waters, the soils,

and the living beings (WCED: 45). In this regard, the definition given in Caring for

the Earth is encompassed by the definition given in Our Common Future.

A second consequence of the above framework, is that it is not, as Meadowcroft

also notes, a particular institution, nor a specific pattern of activity, nor a given

environmental asset which is supposed to be sustained, but rather a process, the

process of development (Meadowcroft, 1996: 3). Or, as Sachs formulates it:

Sustainable development calls for the conservation of development, not for the

conservation of nature (Sachs, 1993: 10). This is a result of the fact that the goal

of development comes logically prior to the proviso of sustainability. This again, has

several important implications.

First, it implies that not every environmental problem is necessarily a sustainable-development issue. This is important because it partly determines how environmental effects are to be judged from a sustainable-development perspective. The

point is concisely put by Malnes: A policy that procures development by dint of

damages to the environment, violates the proviso only insofar as these damages are

detrimental to future development. Policies are not to be judged on account of their

environmental effects as such. This is the World Commissions point of departure

. . . (Malnes, 1990: 7).

It is thus as a prerequisite for development that the injunction to conserve plants

and animals in Our Common Future must initially be understood. It is because the

environment is vulnerable to destruction through development itself that the

constraint of sustainability is placed on the goal of development (WCED: 46; Malnes,

1990: 5). As such, an activity with negative environmental effects is not necessarily contradictory to sustainable development. This is in accordance with Brundtlands own understanding of the idea:

I have often seen it argued that one or another activity cannot be sustainable

because it leads to environmental problems. Unfortunately, it turns out that nearly

all activities lead to one or another form of environmental problem. The question

as to whether something contributes to sustainable development or not, must,

therefore, be answered relatively. We must consider what the condition was prior

to the action undertaken and what the alternative would have been, as well as to

whether the activity could be replaced by other activities. . . . We can be forced to

make difficult, holistic judgments. That is why there have been very mixed feelings

of affection between parts of the environmental movement and the very notion of

sustainable development (Brundtland, 1997: 79, authors translation).

Brundtland seems to be implying here that such a conflict as, for example, that

between Shell Oil and Greenpeace regarding the deep-sea disposal of the Brent

Spar oil platform, could be seen as an activity which is not necessarily contradictory to sustainable development. Although the question of deep-sea disposal is an

important environmental question, the controversy could in this light be portrayed as

peripheral to the broader notion and concerns of sustainable development. (For an

overview of the Brent Spar controversy, see Dickson and McCulloch, 1996.)

A second implication of the above interpretation (whereby it is the process of development which is to be sustained), is that an activity which is not itself sustainable

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

135

could be a part of an ongoing process which is sustainable (Meadowcroft, 1996). This

applies not only to social behavior, but also to activities like the consumption of renewable and non-renewable resources. If this were not so, non-renewable resources could

not be consumed at all. Furthermore, and contrary to the two first usages sustainability identified by Dixon and Fallon (1989), the third usage may have implications

for the use of renewable resources contradictory to the first two. Forestry provides a

good illustration of this point. While the two first usages imply using no more than

the annual increase in the resource, or maintaining different aspects of the ecosystem without reducing the physical stock, the third usage makes it possible to speak

of a sustainable reduction of the physical stock. As stated in Our Common Future:

There is nothing inherently wrong with clearing forests for farming, provided that

the land is the best there is for new farming, can support the numbers encouraged

to settle upon it, and is not already serving a more useful function, such as watershed protection. But often forests are cleared without forethought and planning

(WCED: 127).

In this connection, Beckerman (1994b) would appear to be simply wrong in his

assertion that Our Common Future promotes what he refers to as an absolutist

concept of sustainable development, meaning that the environment we find today

must be preserved in all its forms (Beckerman, 1994b: 194). Once again, the

question of what constitutes a specific instance of sustainable development becomes

a matter of degree. Clearing forests for farming can be part of sustainable development if certain conditions are present. Moreover, it is clear that sustainable

development may have quite different implications for different countries, depending on the level of development, availability of resources, size of population, level

of need satisfaction, and the possibilities of substitution between natural and manmade capital.

Sustainable Development and Economic Growth

It is often argued that the reliance on growth and technology in Our Common Future

makes sustainable development a technological fix. Technology and economic

growth no doubt form an important part of the broad strategic framework for

achieving sustainable development. It is, however, much more fine-tuned and

complicated than the technological fix conclusion indicates. In fact, one can argue

that both the opponents and supporters of growth have exaggerated and overemphasized the bias toward growth in Our Common Future, and thus contributed to

the interpretation that sustainable development first and foremost implies

economic growth. Reid (1995), for example, argues that the comprehensiveness and

detail of Our Common Future is overshadowed by the inadequacy of its treatment of

human need and its bias towards economic growth. . . . Without clear specifications

of a new ecologically sound growth, the emphasis on growth will also in effect

counter the potential of technological change to push back the ecological limits

(Reid, 1995: 65). In the same fashion, Verburg and Wiegel (1997) argue that

sustainable development remains anchored in the very strategies by which current

economic growth was achieved.

More important, however, is the fact that Verburg and Wiegel (1997) also argue

that the compatibility between sustainable development and economic growth

depends on the analytical content of the constituent concepts of needs and limitations, as well as other interrelated concepts. These must be specified if definitions

of sustainable development are to have any content at all (Verburg and Wiegel,

136

International Political Science Review 20(2)

1997:251). Failing to take conceptual and normative terms of reference into

account, the idea that sustainable development is the solution to the threat to

environmental degradation remains unclear because it lacks precise formulation

(Verburg and Wiegel, 1997: 251).

What the Brundtland report actually stipulates, however, is that, given current

population growth rates, the goal of reducing poverty requires national income growth

of around 5 percent a year in the developing economies of Asia; 5.5 percent in Latin

America; and 6 percent in Africa and West Asia (WCED: 50). For industrial countries,

the medium term growth recommended was 34 percent. This was claimed to be

necessary in order to let industrial countries play a part in the expanding world

economy. This latter argument has correctly been interpreted as a global trickledown thesis, but this is only one part of the puzzle. The prescribed growth rates

are seen as environmentally and socially sustainable only under the following conditions:

(1) if industrialized nations continue the recent shifts in the content of their growth

towards less material- and energy-intensive activities and the improvement of their

efficiency in using materials and energy (WCED: 51); and (2) a change in the content

of growth, to make it more equitable in its impact, that is, to improve the distribution of income (WCED: 52).

These conditions are further elaborated in Our Common Future, and they must be

seen as complementary aspects of a pro-growth position. The question which then

must be asked, is how these conditions differ from conditions imposed by the

opponents of growth. One of the more prominent of the latter, Herman Daly (1977,

1992, 1993), argues, for examplein much the same fashion and at the same level

of abstractionthat the physical volume of through-put must be minimized. The

matter-energy that comes from the environment as low-entropy raw materials, and

is returned again to the environment as high-entropy waste, must, in other words,

be reduced. This problem is referred to as the problem of scale, and the task is to find

an optimal scale which lies within the earths carrying capacity and which can be

judged as ecologically sustainable. The question we can then pose is whether Our

Common Future addresses the problem of scale at all.

As I see it, it does so in two ways, one direct and the other indirect. The indirect

way is by changing the quality of growth. This implies a change in the content of

GNP towards one which, as in Dalys approach, is less material- and energy-intensive.

The difference, as Robert C. Paehlke (1989) points out, is that Daly thinks the necessary reduction in throughput ultimately will lead to a decline also in GNP. Paehlke

disagrees with this, along with Pezzey (1992), Randers (1994), and several others

including the authors of Our Common Future. These sources base their conclusions on

the assumption that economic growth (i.e., growth in the money value of the annual

production of goods and services) can be uncoupled from physical growth (the growth

in population, energy use, resource use and pollution output).

Whether or not this is possible, however, is first and foremost an empirical

question. The essence of the normative-conceptual position is that GNP should be

made less material- and energy-intensive so as to keep within the bounds of the

ecologically possible. Whether GNP rises or falls is not the primary question, albeit

it is an important one (Jacobs, 1991). It is in this light that the growth debate can,

to a certain degree, be said to have been transcended by the World Commission.

This has, according to Jacobs (1995), had the following effect: By bypassing the

unhelpful debate about zero growth which plagued earlier waves of environmental concern, the term [sustainable development] has helped to create an unprecedented level of at least rhetorical political commitment to the environment. . . its

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

137

very universality has generated a debate about environmental economic policy

which shows no sign of abating (Jacobs, 1995: 65).

But Our Common Future also addresses the question of scale in a more direct

sense. Reflecting arguments made by (for example) Fritsch (1995) and Paehlke

(1989), the report takes a very specific stand on the crucial nature of energy in

the sustainable development equation. The ultimate limits to global development

are said to be determined by two things: the availability of energy and the

biospheres capacity to absorb the by-products of energy use. These limits are

assumed to have thresholds much lower than other material resources, mainly

because of the depletion of oil reserves and the build-up of carbon dioxide leading

to global warming (WCED: 5859). The argument is not that there are no other

possible limits to future global development, but that the limits of energy and

the problem of climate change will be met first, and indeed may already be at

hand.

Few, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), seem

to be aware of the fact that, more than any other problem, global warming is what

underlies many of the World Commissions recommendations. The problem of

climate change is addressed throughout the report (WCED: 2, 5, 8, 14, 22, 3233,

37, 5859, 172176). Contrary to Beckerman (1994a, 1994b, 1995), who sees the

problem of global warming as more or less non-existent, and thus not a threat to

welfare maximization and sustainable development, the assumption in Our

Common Future is that the problem of climate change is real. Moreover, the problem

is seen as both a problem of scale and of global equity, in much the same manner

as seen by the IPCC. The issue involves distribution both between and within

generations.

The scenario underlying the position is quite straightforward. If the poor nations

were to consume the same amount of fossil fuels as the rich nations, this would

most likely result in an ecological disaster. At the same time, however, the goal of

development demands an increase in energy consumption in developing countries (a

presumption which is also expressed in the United Nations Framework Convention

on Climate Change). The principal developmental challenge is thus to meet the

needs of an expanding developing world population (WCED: 54) within a context of

global ecological interdependence. This is substantiated by the following claim from

the IPCC:

Whatever the past and current responsibilities and priorities, it is not possible

for the rich countries to control climate change through the next century by

their own actions alone, however drastic. It is this fact that necessitates global

participation in controlling climate change, and hence, the question of how

equitable it is to distribute efforts to address climate change on a global basis

(IPCC, 1995: 97).

The most radical changes proposed by the Commission in this context are based

on the above understanding of what the most pressing development constraints are.

Reids (1995) assertion that Our Common Future lacks a description of what would

constitute a new ecologically sound growth is, in this perspective, simply wrong.

Producing More with Less (the title of Chapter 8 in Our Common Future), is a

necessary, but not necessarily sufficient condition for sustainable development. To

avoid an ecological disaster due to the problem of climate change, Our Common

Future recommends a low-energy scenario of a 50 percent reduction in primary

energy consumption per capita in industrial countries, to allow for a 30 percent

138

International Political Science Review 20(2)

increase in developing countries within the next 50 years (WCED: 173). This will

require profound structural changes in socio-economic and institutional arrangements and it is an important challenge to global society (WCED: 201). Further, the

Commission believes that there is no other realistic option open to the world for

the 21st century (WCED: 174).

It would appear, therefore, that when Reid (1995) argues that Our Common Future

was reluctant to speak plainly about the reduction of levels of consumption in the

North, and claims further that the report reveals a Northern (pro-Western) bias,

he simply ignores the ultimate limits for global development set in Our Common

Future. The report does not view the level of consumption as a general problem. On

the contrary: Different limits hold for the use of energy, materials, water, and

land (WCED: 45). But the report also clearly states that ultimate limits there are,

and sustainability requires that long before these are reached, the world must

ensure equitable access to the constrained resource [base] and reorient technological efforts to relieve the pressure (WCED: 45).

As far as I can determine it is nowhere stated (as claimed by Dobson [1996: 41])

that the only limits which matter are the limitations imposed by the present state

of technology and social organization. Social organization and technology are

instead seen as crucial for progressive change; they can be managed and improved

(WCED: 8) so that the accumulation of knowledge and the development of technology can enhance the carrying capacity of the resource base (WCED: 45). According

to Adams (1990: 59), this involves a subtle but extremely important transformation of the ecologically-based concept of sustainable development, which leads

beyond concepts of physical sustainability to the socioeconomic context of development. It is apparently because Dobson misinterprets Our Common Future, and

because Reid has a different view on the question of limits, that their conclusions

differ from those in the Commissions report. It is not the case that Our Common

Future lacks a prescription of what would constitute a new ecologically sound growth,

as Reid claims, but that Reid disagrees.

Verburg and Wiegels analysis (1997) of Our Common Future is particularly interesting in this regard. While their discussion sometimes seems to reflect the common

interpretation that Our Common Future is biased toward traditional growth, their

conclusions become far less clear when they address the compatibility between

sustainable development and economic growth within a framework of needs and

limitations, also considering the interrelationship between freedom and solidarity.

What they find herethat sustainability and economic growth cannot simply be

assumed to be conceptually and normatively compatibleis in fact the same

position as taken in Our Common Future.

Sustainable DevelopmentTechnology or Ethics?

In a widely discussed article, Wilfred Beckerman has portrayed the concept of

sustainable development as basically flawed because it mixes together the

technical characteristics of a particular development path with a moral injunction to pursue it (Beckerman, 1994b: 193). Alternatively, Beckerman argues

that sustainable development should be understood purely as a technical

concept, where a sustainable development path is defined simply as one that

can be sustained over a specific period of time. Whether or not it ought to be

followed is a very different matter. In Beckermans view, most definitions of

sustainable development incorporate some form of ethical injunction without

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

139

any apparent recognition of the need to demonstrate why this injunction should

be preferred.

The Norwegian philosopher, Jon Wetlesen (1995), argues that this is also the case

for the Brundtland report. The concept of sustainable development is presented

against a background of assumptions as to moral duties and obligations, without

these being directly accounted for.

As an initial reaction to these positions, it can be maintained that, even though

Our Common Future does not elaborate on the philosophical foundation of moral

duties and obligations, this does not, of course, mean that the position is ill-founded.

Granting the proposition that the moral aspects of the report are more implicit

than explicit, it can nonetheless be maintained that the moral content is clearly

communicated in Our Common Future. The Commission itself proclaims that the

issues raised in the report are of far-reaching importance to the quality of life on

earthindeed, to life itself, and that they have tried to show how human survival

and well-being could depend on success in elevating sustainable development to a

global ethic (WCED: 308). This global ethic is constructed on the assumption of

duties and obligations in a specific historic context of growing ecological awareness,

ecological threats and widening NorthSouth disparities and agendas (McManus,

1996). It is in this broader context that the binding between the goal of development and the proviso of sustainability must be understood as a comprehensive

ethical position.

Thus, while Beckerman (1994b) argues for a technical concept of sustainable

development, Our Common Future explicitly rejects such a strategy. This is hardly

surprising given the Commissions mandate to define aspirational goals for the

world community. What is interesting, however, is that the Commission develops its ethic in an indirect and non-proselytizing manner. The argument rests on

the proposition that the normative and technical issues are inseparable (WCED:

43). Even physical sustainability, it is maintained, cannot be secured unless

development policies pay attention to such considerations as changes in access to

resources and in the distribution of costs and benefits (WCED: 43). Whether a

certain development is physically sustainable will thus depend on both of these

considerations. Changes in access to resources and in the distribution of costs and

benefits form an integral part of the process of determining the level of physical

sustainability.

For example, under a situation where resources are scarce, a distribution in which

a small minority of the worlds population controls most of the resources might be

possible to maintain over a longer period of time than one where scarce resources are

distributed equally among the worlds population. Consequently, the question of what

is physically sustainable cannot be answered without taking into consideration the

question of distribution and determining what one actually wishes to maintain and

develop (Lafferty and Langhelle, 1998). Hence, even the more narrow and technical

concept of physical sustainabilitythe minimum requirement for sustainable developmentcannot be separated from considerations of social justic (WCED: 43).

What, then, is the logical structure of the ethical framework of sustainable development? In the present view, the answer lies in the obvious attempt by the

Commission to link environment and development on a global scale. This can be

demonstrated by an elaboration of the text with respect to the relationship

between social justice and need satisfaction; the connection between social justice

and equal opportunity; and the attempt to give needs a precedence over wants or

desires.

140

International Political Science Review 20(2)

Social Justice as Need Satisfaction

There is a close relationship between need satisfaction and social justice in Our

Common Future. Social justice can be seen as equivalent to the satisfaction of human

needs, which in turn is what constitutes the primary goal of development in

sustainable development (Lafferty and Langhelle, 1995; Lafferty, 1996; Langhelle,

1996). The proviso of sustainability, on the other hand, is a precondition for social

justice between generations, since violating the sustainability constraint would

undermine the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Moreover,

the concern for social equity between generations must, it is claimed, logically be

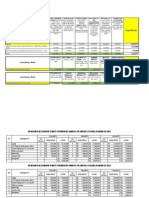

extended to equity within each generation (WCED: 43). This provides (as illustrated in Figure 1) two different dimensions of justice in the concept of sustainable development.

Temporal

Dimension

Geographical Dimension

National

Global

Within a

generation

I. Social justice within

a current national

generation

II. Social justice within

a current global

generation

Across

generations

III. Social justice

across national

generations

IV. Social justice

across global

generations

FIGURE 1. Geographical and Temporal Dimensions of Sustainable Development.

Yet it is not self-evident as to why a concern for social justice between generations logically should be extended to justice within each generation. At the outset,

the rationale seems to hinge on the empirical claim that poverty is a major cause

and effect of global environmental problems (WCED: 3), and that a world in which

poverty and inequity are endemic will always be prone to ecological and other crisis

(WCED: 44). These are empirical claims, and by them the Commission argues that

social justice is a precondition also for sustainability. Thus, the reduction of poverty

itself is a precondition for environmentally sound development (WCED: 69). It can

still be argued, however, that the reciprocal relationship between environmental

problems and poverty only partly explains the logic between inter- and intragenerational justice, and that this empirical foundation is, in fact, a weak one. The

nature of the relationship has been challenged by several authors, and it has been

argued that the povertyenvironment thesis is simply wrong (The Ecologist, 1993, and

Angelsen, 1997). But the problematic can be interpreted in different ways.

First, it can be interpreted strictly as an empirical hypothesis. Brundtland (1997)

states that the thesis is empirically true, if not for all environmental problems, at

least for many. The debate on the povertyenvironment relationship seems,

however, to be inflated by an underlying disagreement as to what the most serious

environmental problems consist of. Are they the type of problems created by the

rich, industrialized countries? Or are they, rather, the problems resulting from overpopulation and poverty in the under-developed South? In general, there seems to

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

141

be an emerging agreement that there are isolated instances whereby the exigencies of poverty in the South contribute to local problems, but that the problems

created by the wealthier countries of the Northparticularly climate change and

ozone depletionare clearly more serious on a global level.

Second, the povertyenvironment thesis has been viewed as a political necessity for the Commission. To prevent a NorthSouth confrontation, it was necessary for the WCED to link economic development and environmental questions in

a positive way. If poverty is a major cause of environmental problems, and

economic growth contributes to the reduction of poverty, economic growth will

also be good for the environment, and thereby contribute indirectly to the solving

of environmental problems (Angelsen, 1997). Economic growth, in this view,

implies that you actually can have your cake and eat it too, so that sustainable

development becomes consistent with the ambitions of developing countries for

growth and progress.

While this interpretation may have some truth in it, it does not explain the fact

that the G77 countries, at the Special Session of the UN devoted to an assessment

of progress on Agenda 21 in New York in June of 1997, consistently tried to substitute sustainable economic growth for sustainable development in the final

document (Nyborg, 1997). If sustainable development is widely understood to

imply economic growth, why would China and the other under-developed countries

view it as too constraining?

A third perspective on the povertyenvironment thesis is to view the priority

given to the worlds poor as independent of the thesis. That is, even if the thesis is

wrong and there is no clear dependency between poverty and environmental degradation, the underlying framework of Our Common Future would still lead to a prioritization of the essential needs of the worlds poor. As stated in the report, poverty

is an evil in itself (WCED: 8), and sustainable development requires meeting the

basic needs of all, thus extending to all the opportunity to fulfill aspirations for a

better life (WCED: 8). This ethical foundation also explains the logic between

intra-generational and inter-generational justice.

The point can be illustrated in the obverse by looking at definitions of sustainable development which exclude the intra-generational dimension of equity.

Amundsen et al., (1991) argue, for example, that the term sustainable development should be limited to the question of inter-generational justice. Their definition is that: Development is sustainable if it is possible and the living conditions

of the generations are non-diminishing throughout the development (Amundsen

et al., 1991: 21). A similar understanding can be found in the description by the

IPCC of what they refer to as the economic concept of sustainable development,

where the focus is placed solely on inter-temporal equity, capital accumulation and

sustainability (IPCC, 1995: 40).

The exclusion of the intra-generational dimension in these cases not only runs

counter to the overriding priority in Our Common Futureto meet the essential needs

of the worlds poorbut also to sustainable development as an aspirational goal

since sustainable development would then be consistent with massive poverty and

miserable living conditions for the majority of the worlds population. Aside from

offering an extremely bad bargain for the worlds poor, this conceals the fact that

living conditions, to a large extent, determine both individual life-chances and the

very composition of future generations (Lafferty and Langhelle, 1995). Why bother

about inter-generational equity if your own children have very poor chances of

reaching adulthood?

142

International Political Science Review 20(2)

There is in other words a logical connection between equity within and between

generations in the definition of sustainable development. The priority given to the

worlds poor is a moral constraint on possible alternative developmental paths or

trajectories. More precisely, it can be seen as an attempt to rule out the very

premise underlying Garett Hardins lifeboat ethics:

. . .each rich nation amounts to a lifeboat full of comparatively rich people. The

poor of the world are in other, much more crowded lifeboats. Continuously, so

to speak, the poor fall out of their lifeboats and swim for a while in the water

outside, hoping to be admitted to a rich lifeboat, or in some other way to

benefit from the goodies on board. What should the passengers on a rich

lifeboat do? This is the central problem of the ethics of the lifeboat (Hardin,

1977: 262).

The answer provided by Hardin is that no further swimmers should be

admitted to the boat. If sustainable development were a purely technical

concept, the option favored by Hardingiven the assumption that the developmental path in question was sustainable in a physical sensewould be a valid

option for a sustainable development. If only a purely technical concept, the

policy implications of sustainable development would thus be open-ended in

this sense.

Sustainable development is, however, logically constructed in such a way as to

rule out the above possibility. The basic message is that any attempt to prevent

poor people from damaging nature by trying to keep them poor is not an option

consistent with the basic concept and strategic framework of sustainable development: you cannot sacrifice todays poor in the name of salvation for future generations. Sustainable development requires meeting the basic needs of all and

extending to all the opportunity to satisfy their aspirations for a better life (WCED:

44). In short, as the very title Our Common Future indicates lifeboat ethics is ruled

out. There is only one boat and we either make it seaworthy for everyone or we all

sink.

Finally, we can view the povertyenvironment problematic as part of an ideological discourse. Our Common Future can be (and has been) interpreted as an attempt

to create a global social-democratic ideology, a necessary antidote to global neoliberalism. Adams, for example, takes this position when he refers to the idea as

part of a rather comfortable Keynesian reformism at the global level (Adams,

1990: 65). McManus argues that the seductive notion of sustainable development

formed an effective counter-hegemonic rallying point for recovering the initiative

from both neo-liberalism and existing socialism (McManus, 1996: 51). Need satisfaction, full employment, economic growth, redistribution, and social justice have

also been key concepts in the social-democratic tradition. Gro Harlem Brundtland

provides indirect support for this view when she both stresses the dominant conservative credo dominating much of Western politics at the time when the Commission was appointed, and also refers to previous UN commissions (those named after

Willy Brandt and Oluf Palme) as social-democratic responses to prevailing trends

(Brundtland, 1997: 7576).

Social Justice as Equal Opportunity

Another important aspect of the ethical framework of Our Common Future is the

principle of equal opportunity. While basic needs are the starting point, the

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

143

developmental goal of social justice can also be seen as reflecting liberal values

which go beyond the mere satisfaction of human needs. This part of the framework is perhaps the most difficult to detect, but there are several passages which

can be seen as reflecting an equal opportunity principle both within and between

generations. The following can be seen as applying to the relationship between

generations: The loss of plant and animal species can greatly limit the options

of future generations; so sustainable development requires the conservation of

plant and animal species (WCED: 46). This same argument is used concerning

non-renewable resources: Sustainable development requires that the rate of

depletion of non-renewable resources should foreclose as few options as possible

(WCED: 46).

The equal opportunity principle is also expressed as a principle within our own

generation: . . .sustainable development requires that societies meet human needs

both by increasing productive potential and by ensuring equitable opportunities for

all (WCED: 44). And further: What is required is a new approach in which all

nations aim at a type of development that integrates production with resource

conservation and enhancement, and that links both to the provision for all of an

adequate livelihood base and equitable access to resources (WCED: 39). The equal

opportunity principle should thus be seen as an inherent part of the concept of

sustainable development.

Moreover, the principle can be seen as more constraining with respect to possible developmental paths than the basic needs approach. While securing basic needs

for future generations can be linked to the minimum requirement for sustainable

developmentphysical sustainabilitythe equal opportunity principle between

generations (as indicated in the above quotation) also requires the conservation of

plant and animal species. This partly explains the relatively ambitious targets for

conservation indicated in Our Common Future (WCED: 166), to the effect that the total

expanse of protected areas should be at least tripled in order to constitute a representative sample of the worlds ecosystems.

Needs, Desires, and Limits

Finally, the concept of sustainable development seems to indicate that the fulfillment of essential needs (sustenance, basic health, work, energy, housing, water

supply, sanitation) should take precedence over the pursuit of personal desires in

case of conflict. This principle applies to both intra- and inter-generational justice.

Verburg and Wiegel (1997) argue that this, in effect, implies that solidarity is to

be put on an equal footing with liberty. The concept of liberty, they argue, is often

defined in relation to the concepts of needs and limitations; as, for example, in

Berlins (1968) usage of the term, where liberty is identified with the absence of

obstacles to the fulfillment of mans desires. The concept of sustainable development, on the other hand, demands that desires be constrained in order to

safeguard the fulfillment of essential needs. Our Common Future expresses in this

regard what Verburg and Wiegel term humanistic solidarity: a sentiment based

upon feelings of consideration experienced with respect to others as fellow

humans, connected with a provision for essential needs to guarantee an acceptable level of quality of life (Verburg and Wiegel, 1997: 258). As the following

indicates, their reading of Our Common Future places the concept clearly at the

equality end of Sabines (1952) classic libertyequality trade-off within

Western liberalism:

144

International Political Science Review 20(2)

By giving priority to the essential needs out of consideration of solidarity and

environmental concern, and by the appeal to effectuate a constraining of needs

in the affluent West to bring back the pursuit of desires within the limits

imposed by the carrying capacity of ecosystems, the characteristic interpretations of the concept of liberty and solidarity in the modern frame of reference

are challenged. The overriding importance attached to the fulfillment of essential needs implies that the idea of humanistic solidarity is part and parcel of

sustainable development, not an appendage to the concept of liberty (Verburg

and Wiegel, 1997: 259).

This interpretation is apparently also in line with Gro Harlem Brundtlands own

understanding. The concept of sustainable development signaled, in her view, a

new solidarity both within and between generations (Brundtland, 1997). When

Verburg and Wiegel conclude that this position discredits the justification for

economic growth, however, they argue as if the growth prescribed in Our Common

Future is economic growth in a traditional sense, ignoring that the Commission also

viewed limitations on personal wants as closely tied to the ultimate (ecological)

limits for global development. This is expressed in the following:

Living standards that go beyond the basic minimum are sustainable only if

consumption standards everywhere have regard for long-term sustainability. Yet

many of us live beyond the worlds ecological means, for instance in our patterns

of energy use. Perceived needs are socially and culturally determined, and

sustainable development requires the promotion of values that encourage

consumption standards that are within the bounds of the ecological possible and

to which all can reasonably aspire (WCED: 44, authors emphasis).

The concept of needs is integral to the WCEDs understanding of sustainable development, even though the report (as pointed out by Reid [1995]), devotes little attention to an elaboration of the idea. Beckerman (1994b) argues in this connection

that, since needs are a subjective concept, the definition of sustainable development in Our Common Future is totally useless. It offers no clear guidance as to what

has to be preserved in order to cover the needs of future generations, because

people at different points in time, and in different cultural and national settings,

will differ with respect to the needs they regard as important (Beckerman, 1994b:

194).

I would maintain, however, that criticism of the report on this count is seriously

overdone. One can readily admit that there will be differences in the perception of

needs without judging the concept useless for sustainable development. The needs

identified in Our Common Future are in fact quite specific, and can, as with John

Rawlss (1971) concept of primary goods, be seen as a general means of livelihood

which every individual needs no matter what ones subjective life-project (see

Amundsen et al., 1991). It is hard to see how the need for work, food, energy, and

the linked basic needs of housing, water supply, sanitation, and healthcare, can be

deemed irrelevant for future politics.

Moreover, many of the recommendations found in Our Common Future are based on

the specific assumption that needs, to a large degree, are socially and culturally

constructed. The question of which needs should be changed or curbed depends on

the limits set for global development. Just as Our Common Future refuses to treat

consumption as a general problem (since there are different limits for the use of

energy, materials, water, and land), there is no reason to change needs and interests

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

145

which can be pursued without damage to the potential need satisfaction of others,

either now or in the future. There is, for example, no prima facie reason to try to curb

the need for education, social integration or aesthetics.

The discussion of needs can also be related to Malness (1995) differentiation

between stern and lenient interpretations of sustainability. Malnes points

out that, when it is maintained that sustainable development requires the

promotion of values that encourage consumption standards that are within the

bounds of the ecologically possible and to which all can reasonably aspire, this

implies that contemporaries, rather than being held to a stern demand of lowering their ambitions right away, may take the time to foster new values and behavior which reflect the broad principles of sustainability. If the concept of need is

seen within the broader framework of carrying capacity, the urgency of new values

and behavior will depend on the limits and resources involved. The difference

between stern and lenient demands will then depend on how close one comes to

the limits of nature in each case and the risks involved in additional need satisfaction.

Sustainable Development as a Basis for Global Partnership

It is generally accepted that the idea of sustainable development put forth in Our

Common Future was primarily designed to provide a normativeconceptual bridge

for joining environmental concerns with developmental possibilities. The policy

implications which flow from this framework are dependent upon the assumptions made about limitsecological, social, cultural, technological, economic,

and, not least, political: In the final analysis, sustainable development must rest

on political will (WCED: 9). Sustainable development defined a developmental

path, or trajectory, which in the Commissions view, could sustain human

progress, not just in a few places for a few years, but for the entire planet into

the distant future (WCED: 4). It was within this context that the Commission

aspired to overcome the widening disparities and agendas between the North and

the South.

The Commission stressed that the term development was to be used in its

broadest sense. This implied that sustainable development required change in every

country: The word [development] is often taken to refer to the processes of

economic and social change in the third world. But the integration of environment

and development is required in every country, rich and poor. The pursuit of sustainable development requires changes in the domestic and international policies of

every nation (WCED: 40).

While economic growth is seen as necessary to solve the problems of underdevelopment and poverty, the new era of economic growth is seen as neither

problem-free, nor as equal for developing and developed countries. Sustainable

development requires economic growth where essential needs are not being met.

Elsewhere, economic growth is consistent with sustainability only if the content of

growth reflects the broad principles of sustainability (WCED: 44). Furthermore,

rapid economic growth combined with deteriorating income distribution is seen as

worse than slower economic growth combined with redistribution in favor of the

poor (WCED: 52).

Accordingly, the basic concept and the underlying strategic framework for

sustainable development lay the basis for a global partnership in which the demands

and challenges are different for developing and developed countries. The main

146

International Political Science Review 20(2)

challenge for developing countries is to eradicate poverty and pursue an environmentally sensitive development through economic growth and internal redistribution. The task for developed countries is threefold: (1) to assist in the eradication

of poverty by substantial increases in development aid; (2) to change consumption

and production patterns by reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions so as

to allow for necessary increases in developing countries; and (3) to develop and

transfer environmentally sound technology so as to smooth the transition to a more

sustainable developmental path or trajectory. In addition, developed and developing countries together, should triple the total expanse of protected areas in order

to conserve a representative sample of the earths ecosystems.

It is important to acknowledge in this connection that the Commission does not

exonerate developing countries from adopting more sustainable patterns of

production and consumption: The simple duplication in the developing world of

industrial countries energy use patterns is neither feasible nor desirable (WCED:

59). It is the changed (or sustainable) consumption and production patterns

primarily with respect to reduced energy consumption and CO2 emissionswhich

should be duplicated. This presupposes, however, that there actually exist alternative consumption and production patterns which can be duplicated. Unfortunately, it appears today that, with both energy consumption and CO2 emissions

increasing in most developed countries, there is as yet little or nothing to duplicate.

The goal and essence of the global partnershipa division of labor between

developing and developed countries and a strategic framework for the realization

of sustainable developmentare nonetheless accessible as a general program in

Our Common Future. The Commission outlined a developmental path, or trajectory,

which, in theory at any rate, would remedy the global environmental and developmental crisisa path which the present analysis has tried to demonstrate as

coherent, integrated, and comprehensive enough to warrant the label of a global

ethic.

Concluding Remarks

Our Common Future addresses, of course, numerous questions and issues which have

not been discussed in this article: the role of technology and the international

economy, population growth, food security, industry, the urban challenge, the fate

of the commons, peace and security, proposals for institutional and legal change,

among others. The purpose of the present exercise however has been to give an

interpretation of Our Common Future in Taylors (1985) sense of the term: to bring

to light what I believe to be an underlying coherence and sense in a text which has

too often been portrayed as confused and contradictory. Without denying that the

Brundtland report is open to different interpretations, I have nonetheless

maintained that there exists a basic concept and broad strategic framework in

the document. By way of conclusion, let me try to draw out at least one major implication of this perspective.

Several recent commentators have viewed the results of the UNCED process as a

reordering of the priorities of Our Common Future, with Agenda 21, in particular,

portrayed as having tipped the environmentdevelopment balance back in an

environmental, more market-oriented direction (Middleton, OKeefe, and Moyo,

1993; Kirkby, OKeefe, and Timberlake, 1995; and McManus, 1996). Agenda 21 was

also, in fact, heavily criticized by the Norwegian government for not being willing

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

147

to allocate priorities among the different issues addressed (Ministry of Environment, 199293). The priority to meet the essential needs of the worlds poor (the

initial qualifying key concept) has, it is maintained, more or less disappeared as

an overriding priority. The global partnership prescribed in Our Common Future is

thus yet to be seen.

One might even try to explain this by pointing out that, with respect to climate

change, at least, the reduction of poverty itself does not seem to be a precondition

for an environmentally sound development. The opposite may, in fact, be the case,

and if so, we would have to revert to other, more purely moral and ideological,

reasons for combating global poverty. Southern countries have, however, made it

increasingly clear that they will not accept limits to growth that the countries of

the North have not been willing to impose upon themselves, so we are left with an

increasingly precarious need for the type of integrated environment-and-development logic put forth in Our Common Future.

In this light, it is vital to retain an understanding of the concept of sustainable

development as an overall normativestrategic framework for continuing to work

out in detail the necessary balance between physical sustainability, generational

equity and global solidarity, not as a fixed blueprint for similar developmental

paths for all countries, but as a set of basically integrated concepts and values pointing in a genuinely different alternative direction. At a minimum, the notion offers an

obviously moral, and tauntingly pragmatic, solution to a wealth of increasingly

perilous problems. As an alternative to lifeboat ethics, I have argued that the

normativestrategic message of Our Common Future is more clear, more conceptually

consistent, and more potentially relevant today than its numerous critics are willing

to credit.

The overriding message of Our Common Future is that the global complex of

environment-and-development problems cannot be addressed in an integrated way

without taking simultaneously into account the three core elements of physical

sustainability, generational justice and global solidarity. Sustainable development

provides conceptual tools for the task and stipulates a global partnership in which

the pressing NorthSouth disparities and agendas might be overcome.

References

Adams, W.M. (1990). Green Development. Environment and Sustainability in the Third World.

London: Routledge.

Amundsen, et al. (1991). Hva er brekraftig utvikling? Sosialkonomen, (3): 2026.

Angelsen, A. (1997). Miljproblemer og konomisk utvikling: Bidrar vekst til bedre eller

delegge miljet? Sosialkonomen, (7): 2028.

Beckerman, W. (1994a). Foreword. In Global Warming: Apocalypse or Hot Air? (R. Bate and J.

Morris, eds.). IEA Studies on the Environment, No. 1.

Beckerman, W. (1994b). Sustainable Development: Is it a Useful Concept? Environmental

Values, 3 (3): 191209.

Beckerman, W. (1995). How would you like your Sustainability, Sir? Weak or Strong? A

Reply to My Critics. Environmental Values, 4: 169179.

Berlin, I. (1968). Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brundtland, G.H. (1997). Verdenskommisjonen for milj og utvikling ti r etter: Hvor str

vi i dag? (The World Commission for Environment and Development: Where Do We

Stand Today?). ProSus: Tidsskrift for et brekraftig samfunn, (4): 7585.

Daly, H.E. (1977). Steady-State Economics. The Economics of Biophysical Equilibrium and Moral

Growth. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company.

148

International Political Science Review 20(2)

Daly, H.E. (1992). Allocation, distribution, and scale: Towards an economics that is efficient,

just and sustainable. Ecological Economics, 6 (3): 185193.

Daly, H.E. (1993). The economists response to ecological issues. In Sustainable Growth: A

Contradiction in Terms? (Report of the Vissert Hooft Memorial Consultation). The Ecumenical Institute, Chteau de Bossey, pp. 3952.

Dickson, L. and A. McCulloch (1996). Shell, the Brent Spar and Greenpeace: A Doomed

Tryst. Environmental Politics, 5 (1): 122129.

Dixon, J.A. and L.A. Fallon (1989). The Concept of Sustainability: Origins, Extensions, and

Usefulness for Policy. Washington: The World Bank, Environment Department, Division

Working Paper No. 19891.

Dobson, A. (1996). Environment Sustainabilities: An Analysis and a Typology. Environmental Politics, 5 (3): 401428.

The Ecologist (1993). Whose Common Future? Reclaiming the Commons. London: Earthscan Publications.

Fritsch, B. (1995). On the Way to Ecologically Sustainable Economic Growth. International

Political Science Review, 16 (4): 361374.

Hardin, G. (1977). Living on a Lifeboat. In Managing the Commons, (G. Hardin and J. Baden,

eds.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

IPCC (1995). Climate Change 1995. Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contributions

of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IUCN/UNEP/WWF (1980). World Conservation Strategy. Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable

Development. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

IUCN/UNEP/WWF (1991). Caring for the Earth. A Strategy for Sustainable Living. Gland, Switzerland:

IUCN.

Jacob, M.L. (1996). Sustainable Development: A Reconstructive Critique of the United Nations Debate.

Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Jacobs, M. (1991). The Green Economy. Environment, Sustainable Development and the Politics of the

Future. London: Pluto Press.

Jacobs, M. (1995). Sustainable Development, Capital Substitution and Economic Humility:

A Response to Beckerman. Environmental Values, 4: 5768.

Kirkby, J., P. OKeefe and L. Timberlake (eds) (1995). The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Development. London: Earthscan.

LaCourt, T.D. (1990). Beyond Brundtland: Green Development in the 1990s. London: Zed Books.

Lafferty, W.M. (1996). The Politics of Sustainable Development: Global Norms for National

Implementation. Environmental Politics, 5 (2): 185208.

Lafferty, W.M. and O. Langhelle (eds) (1995). Brekraftig utvikling: Om utviklingens ml og

brekraftens betingelser. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal.

Lafferty, W.M. and O. Langhelle (eds) (1998). Towards Sustainable Development: The Goals of

Development and the Conditions of Sustainability. London: Macmillan Press.

Langhelle, O. (1996). Sustainable Development and Social Justice. Paper presented at

the IPSA Roundtable on The Politics of Sustainable Development, Oslo, Norway, 26

April.

Malnes, R. (1990). The Environment and Duties to Future Generations. Oslo: Fridtjof Nansen Institute.

Malnes, R. (1995). Valuing the environment. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

McManus, P. (1996). Contested Terrains: Politics, Stories and Discourses of Sustainability.

Environmental Politics, 5 (1): 4873.

Meadowcroft, J. (1996). Planning, Democracy and the Demands of Sustainable Development. Paper presented at IPSA Roundtable on The Politics of Sustainable Development,

Oslo, Norway, 26 April.

Middleton, N., P. OKeefe and S. Moyo (1993). The Tears of the Crocodile: From Rio to Reality in

the Developing World. London: Pluto Press.

Ministry of the Environment (199293). St. meld. nr 13 om FN-konferansen om milj og utvikling

i Rio De Janeiro. White paper No. 13, Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment.

LANGHELLE: Exploring the Ethics of Our Common Future

149

Murcott, S. (1997) Appendix A: Definitions of Sustainable Development. http:/www.sustainableliving.org/appen-a.htm.

Nyborg, M. (1997). Earth Summit + 5: Nedtur i New York. ProSus. Tidsskrift for et brekraftig

samfunn, 3: 4555.

ORiordan, T. (1993). The Politics of Sustainability. In Sustainable Environmental Economics

and Management. Principles and Practice (K.R. Turner, ed.). London: Belhaven Press.

Paehlke, R.E. (1989). Environmentalism and the Future of Progressive Politics. New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Pezzey, J. (1992). Sustainability: An Interdisciplinary Guide. Environmental Values, 1 (4):

321362.

Randers, J. (1994). The Quest for a Sustainable Society: A Global Perspective. In The Notion

of Sustainability and its Normative Implications (G. Skirbekk, ed.). Oslo and Bergen: Scandinavian University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Social Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Redclift, M. (1993). Sustainable Development: Needs, Values, Rights. Environmental Values,

2 (1): 320.

Reid, D. (1995). Sustainable Development: An Introductory Guide. London: Earthscan.

Sabine, G.H. (1952). The Two Democratic Traditions. Philosophical Review, 61: 451474.

Sachs, W. (1993). Global Ecology and the Shadow of Development. In Global Ecology. A

New Arena of Political Conflict (W. Sachs, ed.). London: Zed Books.

Soussan, J.G. (1992). Sustainable Development. In Environmental Issues in the 1990s (S.R.

Bowlby and A.M. Mannion, eds.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Taylor, C. (1985). Interpretation and the Sciences of Man. In Philosophy and the Human

Sciences: Philosophical Papers 2 (C. Taylor, ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verburg and Wiegel (1997). On the Compatibility of Sustainability and Economic Growth.

Environmental Ethics, 19: 247265.

WCED (The World Commission on Environment and Development) (1987). Our Common Future.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wetlesen, J. (1995). En global brekraftig etikk? In Brekraftig Utvikling. Om Utviklingens

ml og brekraftens betingelser (W.M. Lafferty and O. Langhelle, eds.). Oslo: Ad Notam

Gyldendal.