Escolar Documentos

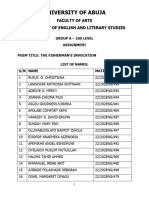

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory Among The Bukusu

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory Among The Bukusu

Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS)

Volume 19, Issue 12, Ver. III (Dec. 2014), PP 30-39

e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845.

www.iosrjournals.org

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the

Bukusu

Michael Maelo

Moi University

Abstract: Khuswala kumuse (funeral oratory) is a central rite among the Babukusu. It is a significant ritual

that defines their worldview and how they relate with their cosmology and themselves. Given its centrality in the

Bukusu cosmology, it is important to examine how the orator puts to use language to construct meanings that

enables this society to understand itself. This paper is an investigation of how the content and structure of the

Bukusu funeral oratory contribute to the overall understanding of the Babukusu historical heritage. Data was

collected from pre-recorded cassette tapes of speeches of Manguliechi (a renowned Bukusu orator) and video

tapes of the performance of khuswala kumuse ritual for the late Vice-president of the Republic of Kenya Michael

Kijana Wamalwa (purchased from Kenya Broadcasting Cooperation, marketing department). These were

transcribed and translated into English and generalizations made on the content and context. It was for example

noted that the ritual is a form of epic recreating the history of Babukusu. Its structure makes use of a stylized

beginning and ending with poetic language. Its content touches on several aspects such as health, politics and

economics. This helps in the understanding of Babukusu.

Key Words: Funeral Oratory, Content, Context, Structure, Oral Literature

I.

Introduction

Historically, Babukusu are a part of the seventeen or so sub-ethnic groups that constitute the Luhya

community of western Kenya. They belong to the larger Bantu speaking group. There is a strong relationship

between the history of the Babukusu and the funeral oratory ritual known as khuswala kumuse. For example, the

oral artist details the history, culture, law and traditions of the community in the oration. He thus reminds people

about their ethnic background. He also exhorts the members of the community to live up to the work of heroes

and the moral rectitude and courage of the community. Some songs in the oration refer to hard times in the past,

for instance, when the Babukusu experienced war with other communities and her resistance to colonial rule.

To a great extent, khuswala kumuse represents Bukusu cosmological identity. It is a reflection of

belief systems of the people. The performer perceives himself as the custodian of social customs and values that

are at the heart of the Babukusu. In fact the artist often mentions multifarious aspects of his society such as

material culture, food stuffs, marriage, customs, types of divination and a host of other catalogues reflecting, or

at least attempting to demonstrate the bard knowledge of his cultural traditions. Besides, the oration presents a

truer picture of popular beliefs about death, myths, traditional songs and modern poetry.

Therefore, the ritual oratory can be in a way read as a narrative of the history of Babukusu community

viewed by the oral artist. Indeed, the ritual performer is considered as a chronicler of the history of Babukusu.

This paper is an examination of how different aspects of the structure of the funeral oratory fits into the

historical context of the Bukusu.

II.

Classification Of The Ritual

The Bukusu society has what could be referred to as one of the highly diverse and stimulating artistic

tradition. The funeral oratory is part of this tradition. It is a unique form that defies any attempts to confine it

within a neat and unproblematic Eurocentric generic classification. What Amuka (1994:6) would refer to as

academic convention of compartmentalizing and dismembering knowledge. Hence it is not possible to

achieve a universal cross-cultural classification even if it becomes convoluted to excess. He continues by saying

that a universal schema will of necessity wrench local taxonomic units apart and lump others together. He

emphasizes the fact that the researcher must be guided by the local name for the genre and the specification of

its requirements. In a similar vein, Okombo (1992:27) argues that

Each community engages in social activities and, at the same time, observes itself and makes value

judgements on its own behaviour. In other words each community turns its own eyes upon itself and looks at

what it does; each community turns its own ears upon itself and listens to its own utterances. On the basis of

what it sees and what it hears, a community describes itself and evaluates its own activities.

www.iosrjournals.org

30 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

Such studies demonstrate the importance of relying on communities for categorization of their verbal

art rather than imposing foreign classification systems and generic names. This is so because every community

has a discourse about itself and it is the role of the researcher to use the communitys nomenclature.

2.1 Genres Of Oral Tradition

Generally speaking, ritual oratory performance embodies most of the oral tradition genres found in the

Bukusu society. For instance, the performer uses many proverbs in his oration mainly as a reflection on human

society, identifiable as proverbs independent of the context of the ritual performance. The proverbs are chosen

in line with the philosophical and artistic aspects of khuswala kumuse performance. Riddles, songs, narratives,

and even drama and elements of epic are incorporated in the oratory. This inclusive nature makes the oratory

endlessly accommodating. Thus its mode is to subsist by swallowing other genres. The performer exploits the

possibilities inherent in this form to achieve remarkable effects. Indeed in the domain of Babukusu

ethnopoetics, khuswala kumuse oratory is one of the most prestigious, aesthetically marked style of speech.

2.2 The Ritual As An Epic

The khuswala kumuse ritual can also be read as an epic. Kunene (1970:20) defines narrative epic as

one that is mainly concerned with important heroic actions in defence of society. He notes that not all nations

are heroic in relation to physical confrontation. Some actions are heroic because they postulate social

directions. He further notes that narrative epic is a literary form, which is more than a simple story. That is

rather a dramatization of significant social events, which must be factual even if the stylization and presentation

require that they be presented in colourful language.

Indeed the khuswala kumuse oratory can be studied as societal epic, spread over several generations.

In the oration, the performer interweaves the theme of family, social and national morality. He highlights the

courage, values and history of Babukusu. The oratory contains myths, legends, genealogies, proverbs and other

stories about the societys past experiences and institutions. For instance the ritual performer highlights the

wars and conquest of Babukusu with other tribes on their immigration route. He refers to the battles with

Kalenjin, Ateso, with whom they fought bitter battles over land and animals.

III.

Setting And Context Of The Performance

Khuswala kumuse is a rare, an elaborate and lengthy ceremony performed in honor of a respected

Bukusu elder. The performer is invited three days after the noise and bustle of the actual burial have subsided.

This is one of the most important events in Babukusus social life, and whenever it is held, many people will

gather from many miles around to witness the performance and listen to the wise words of the performer.

The performance is an oral art work that is quite elaborate and sophisticated with a specialized mode of

expression mastered only by the initiated. Indeed, the ritual is acted out by a specialist. This art of khuswala

kumuse is obtained through inheritance, either from ones paternal or maternal clan. Wanjala (1985:84) makes it

abundantly clear who qualifies to perform the ritual when he notes that, it is believed that an imposter from

non-performing clans who tries the ritual garb on and tries to perform will drop dead in the arena. There are

acute taboos about the very regalia which the ritual leaders put on for the performance.

This specialist is known almost by everyone in the community. He can be compared to griots in West

African societies. These are professional and casted praise singers and tellers of accounts. For example among

the Mandinka, the griot was traditionally a court poet attached to the king for the purpose of singing the kings

glories and recording in his songs important historical events surrounding the ruling family. The same duty was

performed among the Ashanti of Ghana by the court poet known as Kwandwumfo; among the Rwandese of

central Africa such a poet was called an umusizi; among the Zulu of southern Africa, the Imbongi (praise singer)

traditionally played that role; and so forth (Okpewho, 1985:4). In the same vein, oswala kumuse can be

compared to ministerial and master of ceremonies at funerals among the Luo people (Wanjala, 1985:82). As

aforementioned the ritual performer is specialized and initiated in the traditions of the ritual and he enjoys

prestige status as a wise person, hired and paid for his services. He is such a truly encyclopedic person, with rich

and sharp knowledge about all aspects of his communitys history and customs.

The ritual is performed in honour of old men who have gone through all rites of passage demanded by

their community and who have witnessed their own grandchild circumcised. There are exceptions though as in

Nangendo (1994:150) reminds us, the rituals can be performed on the basis of ones age (kamase kamakora)

and maturity (buangafu) even if one had no male grandchildren.

The ritual performer occupies space created for him by the audience. He is a powerful figure, a

religious icon, a seer, a prophet. Oswala kumuse is a leader of great wisdom. He is admired, revered and even

feared by the society. He is an opinion shaper; his oratory influences the attitudes, thoughts and actions of the

members of the Bukusu society. The performer is a bearer of the fire. He alone knows the mystery of the

supernatural. He is such an important functionary, who, in fact belongs to the sacred order. He has direct

www.iosrjournals.org

31 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

access to members of his lineage in the spirit world. He plays a role of being an intermediary of the living and

the ancestors. The ritual oratory is therefore one of the means through which the profane world is brought into

contact with the sacred world.

The ceremony usually starts in the morning at about 8.00a.m. It lasts for approximately three hours.

When oswala kumuse arrives in the deceaseds homestead, he normally finds mourners already seated,

expecting him. The funeral congregation normally sits in half-circle, with women and children on the left hand

side and men on the right hand side. The widow(s) and children of the deceased sit on the side of women with

their legs stretched.

The performer is escorted to the scene of performance by the hosts. He then makes his way into the

circle formed by the funeral assembly. Before the performer starts the oration, he normally walks to and fro in

the middle of the circle in total silence, creating a line, which is called kumuse. At the end of the line he has

formed, he stops and drives his rod into the ground. The hole created by the rod marks one end of kumuse. On

this created path, oswala kumuse will walk and trot throughout the khuswala kumuse session. He speaks for the

first time while walking back from the small hole created by the rod (Wanjala, 1985:8).

In most cases, the oral artist begins his oration by commenting on the nature of death. He reminds

people that they are all mortal and that death has been in existence since time immemorial. Death is depicted as

inescapable. Oswala kumuse therefore encourages people to take heart and never lose hope. He also counsels

and consoles the bereaved. He preaches against social ills such as laziness, extravagance, bearing false witness,

contempt towards the poor, witchcraft, theft, envy, violence, loose morals, and lack of respect for elders. He

does also narrate the history of the tribe, its heroes, social organizations and traditions.

Towards the end of the performance, oswala kumuse runs three times from one end of the kumuse to

the other. This process is referred to as khusoma (wandering). This is the time he specifically mourns the

deceased since he is not supposed to shed tears like other ordinary mortals. To do so would be to appear weak

before the very people he is to protect. At this stage, he beseeches God to take care of the bereaved and to

welcome home the deceased person. He says, oli khumuliango kwase okhongonda ndimwikulila, papa Wele

nakhongonda khumuliago,ikula kube khwasie (you said that whoever is on my door and knocks, I will open

for him, God our father, see I knock on the door, open the door and let it remain wide open).

3.1 Superstitions

There are a number of superstitions that are associated with the ritual and also talked about in the

course of the performance of the ritual. These are part and parcel of the context and setting of the ceremony.

3.1.1 Performer Superstitions

On the eve of the performance of the ritual, oswala kumuse abstains from having sex with his wife to

keep the purity and sanctity of the ritual. In case the performer fails to observe this, then it is believed that

misfortune would befall him.

Again he should not greet anybody nor be greeted while on his way to the ceremony. This is meant to

avoid bad luck of whatever nature that might befall the performer. The performer should enter kumuse while

facing the North. The North is symbolic of origin, or beginning, or birth. The Babukusu believe that their cradle

land is in the North (Egypt). The performer therefore faces the North in honour of the great ancestors of the

community.

During performance of the ritual oswala kumuse should not swallow saliva. In case he salivates, he

spits, but the audience cannot. This shows that he is different from the rest of the people; he mystifies himself.

He also purifies himself. By spitting the performer is symbolically seen as getting rid of anything deemed bad or

unclean. He has to be pure since he is performing a sacred duty and standing on a holy ground. This act can be

compared to Muslims when fasting, they constantly spit; supposedly to keep pure. Swallowing can also be

looked at as being similar to eating. The performer therefore abstains from eating to serve his society and the

deity. Again he should not point his rod at a person unless administering a curse. Such an action is believed to

cause instant death of the person pointed at.

3.1.2 Superstition among the Mourners

Once the ritual oratory is in progress, the mourners are not allowed to walk around, cross the path

created by the performer. The congregation

sits in silence and only responds at the prompting of the

performer. This is meant to maintain order, serenity and solemnity of the occasion.

Sneezing while the ceremony is in session is not allowed by the performer. Sneezing is viewed as an

expression of spite and disgust. As a result, it is assumed that such an action is a show of disrespect towards the

performer and that such a person, is sort of dismissing what is being said. As such, in case one sneezes, she/he

must leave the session immediately.

www.iosrjournals.org

32 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

3.2 The Structure of the ritual

The analysis of the structure of the Bukusu funeral oratory stems from the thesis that structure is an

important aspect since it is a vehicle through which the concepts imbued in the oratory are communicated. This

involves the arrangement of actions, images and episodes that constitute the oratory. These aspects differentiate

the oratory from other utterances and elevate it into an art form.

Indeed the khuswala kumuse text has a discernible internal logic, a sequence of stages; it has a

beginning, middle and an end. The ritual for instance, is performed in the same way as narratives, proverbs,

riddles are performed.

3.2.1 Formulaic Beginning

The ritual has formal and even formulaic framework. It has a kind of opening formula where the

performer begins his oration with an invocation of spiritual powers to guide his performance or some other

introductory device. For example the performer begins by acknowledging the supremacy of Wele (God) as the

sole creator and provider. He also acknowledges his dependence on Wele as his servant. He says, ese

semanyile elomo ta, semanyile khuloma ta, khendeebe Wele wangali, khendeebe Wele Wenche, Wele

Mwana,Wele Kuka,Wele Mukhobe (I do not know the words to speak, I do not know how to speak let me

ask the Truthful One, let me ask God of the Universe, God the Son, God of our ancestors, the Good God).

In so doing, the performer establishes his right to perform by referring to God and sometimes to his

forefathers. This also helps to enhance the sacred mood that prevails during the ritual performance. There are

also formulaic comments to indicate that the performer is about to change his theme in the course of the

performance. These formulae are like sign posts in an essentially homogeneous and endless terrain. Any other

elements including proverbs, riddles, songs and the invocations appealing for spiritual support can appear in any

position in the text.

The formulae are brought into play in response to internal as well as external factors. For instance, if

the performer is addressing an issue, and in the process spots an important figure among the congregation, he

may change the topic to address that person. For instance, he says; Musikari Kombo, nabone wekhale awowo,

wekhale abweenawo (Musikari Kombo I can see you are seated there, you are seated over there).

Hence there is sometimes an impromptu, unplanned character in the text of his oratory or the order in

which ideas are arranged. This kind of shift cannot be said to be a deviation within the text but a way of

accommodating these issues.

3.2.2 Unity in Development

Again the ritual may glide from the mundane to the abstract, a light to sombre mood. As this happens,

a certain unity of development is maintained. This patterning is mainly based on repetition and parallelism,

which are key aspects of structure. Repetition can be of a word, line, idea or phrase which can appear at regular

or random intervals. For example the performer would say:

Enywe babandu ba Kenya. OMuchaluo noli anano, Omunandi noliano, Omumia noliano. Omukikuyu

noli anano,Omumeru noli anano, Omuembu noli anano, Omutiko noli anano ,Omukiriama noli

anano,Omumasaba noli anano. Efwe khumanyile sifuno sia Kenya, menya Mukenya nga Wele nekenya, Linda

Kenya nga Wele nekenya. Wamalwa Linda Kenya nga Wele nekenya. Mukhisa Linda Kenya nga Wele nekenya,

Munyasia Linda Kenya nga Wele nekenya. Bona Wele kenyile semutetea, bona Wele wenyile semulinda,

semulinda sibala.

(You people of Kenya, a Luo if you are here, a Nandi if you are here, a Teso if you are here,a Kikuyu if

you are here, a Meru if you are here, Embu people if you are here present, Digo people if you are here present,

Giriama people if you are here present, Masaba if you are here present. It is you who know the value of Kenya.

Stay in Kenya according to the will of Kenya, love Kenya according to the will of Kenya, and defend Kenya

according to the will of God.Wamalwa defend Kenya according to the Will of God, Mukhisa defend Kenya

according to the Will of God, Munyasia defend Kenya according to the Will of God. Look, God wants you to

protect Kenya, look God wants you to protect, why dont you defend the country).

It is also noted that the internal relationships of the performance are indeterminate. There is no overall

formal pattern to which units are subordinated and which assigns them a particular place in relation to the

others. The performer enjoys considerable freedom limited by habit rather than by rules of the genre to string

them together in whatever order and combination he wishes. Every performance of a particular performance

will seem similar, but the content units will be to a greater or lesser degree differently selected and ordered, and

sometimes differently worded.

The performer of the ritual has scope to recast his materials, recombine them and add new elements by

borrowing. He can borrow biblical material, adopting and sometimes creating fresh composition. For instance

the performer asserts that the biblical Ten Commandments are engraved on peoples palms. When two

individuals shake hands in greetings, their fingers add up to ten, signifying Gods Ten Commandments.

www.iosrjournals.org

33 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

3.2.3 Stylized Ending

The oral artist ends his performances in a stylized form. He will eventually stop, because he is tired, or

because the occasion does not require further performance, or he has exhausted his repertoire. He will then

signal his intention to stop by deploying a formula that says so, or by shifting from a chanting mode into a song.

For example, he sings, thus:

Luyali lwa Wamalwa x2

the goodness of Wamalwa x2

kumoyo kwa Wamalwa

the soul of Wamalwa

kumoyo kwa Michael

the soul of Michael

kuronye wa papa Wele

let it drop before God the father

wa okhwa Nakhombe

son of Nakhombe

aronye wa papa Wele

let it drop before God the father

okhwa Natulo

son of Natulo

aronye wa papa Wele

let him drop before God the father

Wamalwa Kijana oyu

this Wamalwa Kijana

aronye wa papa Wele

let him drop before God the father

He may also use a saying or simply utter a statement such as: onabona engokho etima nende kamala

ke eyasie, yosi balitima nende kamala kayo (when you see a hen running around carrying the intestines of its

own kind, know very well that very soon someone else run with its own intestines)

Indeed the ending of the performance is quite dramatic. The people will stand up at once. The

Babukusu believe that any person left sitting will die. This echoes Turner (1969) when he speaks of grey area

in performance. In a way the ritual oratory is performed in a transcendental space. It is a transition moment

where the performer transports the audience into this estranged space. And so at the end of the performance, he

has to snap them back to the world of reality. Just like in oral narratives, the narrator would say lukano lufwe

,ese njooe (let my tale die, as I grow).

Again the performer exits from the arena in a dramatic way. He does not announce his departure; he

simply drops hints to that effect. He then walks away very fast without looking behind. This act points to

mystery of death; it strikes unnoticed taking away its victim without much ado.

3.3 The Language of the Ritual

Since language is part of ritual, the performers use of language takes a central position in this study. A

number of scholars have noted that language may be viewed as a symbolic system based upon arbitrary rules in

the same way as ritual may be viewed as a symbolic system of acts based on arbitrary rules. This implies that

both language and non-verbal ritual communicate at a symbolic level.

3.3.1 The Performative nature of language

A key aspect that can be noted concerning language and ritual is the performative nature of both.

Indeed ritual behaviour involves established actions which have no rational means. In this respect ritual is

performative because it does not communicate at the ordinary level but at a symbolic one. The language that

accompanies ritual act is like the non-verbal ritual act, especially fashioned for this purpose. It is set apart from

ordinary usage to specialized usage thus making it performative.

In this case, an utterance elicits a response which involves action. For instance, the performers words

and pronouncements are taken so seriously because they have religious implications and people who do not

adhere to them feel a sense of guilt and seek ritual restoration. In essence, the performance of the ritual

therefore does something; uttering the words of the ritual makes something happen, they are performative

utterances, illocutionary acts. These performative utterances achieve certain ends, for instance, they console,

encourage, strengthen the listener(s) and influence their attitudes. It is also a communitarian activity since the

whole community is involved in its performance.

3.3.2 Poetic Language

It is also noted that specialized language use gives the language a sense of musicality and rhythm

which is achieved in the oratory through repetition. It lends to the oratory a certain musical quality which

reflects the rhythmic basis of the poetry tradition. This specialized mode of expression is mastered only by the

initiated performer. The style is full of archaisms, obscure language and highly figurative forms of expression.

This figurative language is used in the oratory to convey abstract ideas in a vivid and imaginative way. It also

adds colour and solemnity to the oratory just like Homeric epithet in Greek epic do. Thus the performers use of

language can be compared to modern poets who use written words to create powerful mental pictures in their

work.

www.iosrjournals.org

34 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

Nevertheless, oswala kumuses poetry may sometime use ribald language otherwise unacceptable in

public. Indeed his terminology may sound offensive to some people hence the performer sometimes conceals

them beneath a cloak of euphemism. In fact the oral artist at times censors himself. For instance he would

remark:

Khaboola, khemboola bali khendoma ndio baboola bali khendoma chilomo chikhwe ta Namwe

khendoma chikhwe? Ta! Esese ndi khengaambila.

(when I speak, when I speak like this, they will say that I am being obscene, Am I being obscene? No!

(the audience answers back). Im just giving my counsel)

The oratory is quite poetic, for instance, it is vocal and tonal. In the oratory, the performer adopts high

tone, sometimes sad, sombre, forceful and sarcastic. The effect, of which, are to provide the right pace and

highlight the mood prevailing in the oratory. Furthermore, the effective poetic use of vocal music is possible

because Lubukusu is highly tonal; a quality that works to the advantage of the oral poet in performance.

However, it is noted that the poetic language used in the oratory is not necessarily used in the conventional way

that it is understood in poetry. The oswala kumuses poetry resonates the form of Okot (1972) Song of Lawino

a poem which draws a lot of its material from traditional songs. Just as the African writers of novels are using

traditional material as a source for their writings, the performer also finds inspiration from the traditional

folklore. As Okot (1973) says, a poem is a poem, whether sung, recited or written. Hence the oswala kumuse

as a literary virtuoso uses different tones ranging from the ordinary to the highly specialized.

3.3.3 Non-Verbal Features of language

The performance of the ritual can in a way be described as a one man show. The performer takes the

stage that is marked out for his performance. He cannot walk outside the marked perimeter. He does not only

utter words, he also employs dramatic elements of oral delivery. He conveys his message through expressions

on his face or grace of gesture as if on stage acting. He also employs movements, abrupt breaks, poignant

pauses, gestures, facial expression and rhetorical questions as he watches the audiences reactions and exploits

his freedom to choose his words as well as his mode of delivery, designed to move the audience. He even works

himself into ecstatic transport of inspiration.

3.4. Audience and Performance

The ceremony involves not only members of the lineage but also all members of the clan living in the

neighborhood and the general public. It is noted that clan solidarity is a vital element among the Babukusu,

binding a man to his living relatives as belief in spirit world binds him to the dead. The ritual is performed

before a public audience in the open space, a distance away from the compound of the deceased person. Unlike

other performances, for example telling of tales, here the audience sits in silence as a sign of veneration for the

sacred performance quite religious. The mood that prevails during the performance can, in a way, be

compared to the solemn mood that prevails in modern churches during worship. However, the audience does not

just sit and watch. The performer engages the audience in his performance. There is constant, dynamic

interaction between the audience and the performer. He provokes this interaction by asking questions, real or

rhetorical. For example the performer asks:

mayi ewe, oli omwana we mungo muno? Nawe papa? Ewe wabonakho Wele? (Laughter from the

audience). Ewe papa wabonakho Wele. Luno tare sina! (tare tisa audience responds). Tare tisa? (yee

Audience responds)Luno khemwekesha Wele mumubone. Mufukilila mubone Wele (yee audience

responds).Mukhalomanga busa muli mumanyile Wele mala mukhamubonakho tawe.

(Hey you my daughter, are you a child to this home? What about you son?

Have you ever seen God? (the audience responds in the negative)

You son, have you ever seen God? (the audience responds in the negative)

What is the date today? (9th audience answers)

Do you wish to see God today? (audience answers in the affirmative)

Dont always say that you know God yet youve never seen him).

Thus, the performer and audience are creating the performance together in the sense that the audience

answers the questions asked. They at times nod in approval and even smile in admiration of the oratory skills of

the performance. By so doing, the performer connects well with his audience.

Oswala kumuse also expects murmurs of support and agreement and even laughter when he purposely

brings up something amusing or exaggerated. For instance in the text, when the oral artist castigates some of

Bukusu political leaders for engaging in self destructive and useless rivalry for tribal political supremacy, the

audience supports and encourages him on by saying,babolele!...toboa!..toboa! ( tell them!..tell it!..tell it!).

www.iosrjournals.org

35 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

Though the audience is always active in the performance, it is noted that there is no competition for

the appropriation of the performance space (Odhiambos (2006:124)). Furthermore, Soyinka (1976:38 - 9) has

noted:

Any individual within the audience knows better than to add his voice arbitrarily even to the most

seductive passages of an invocatory song, or to contribute a refrain to the familiar sequence of liturgical

exchanges among the protagonists. The moment for choric participation is well defined, but this does not imply

that until such a moment, participation ceases.

Accordingly, the performer remains unchallenged during the session. In case he is challenged, he may

retort and try to defend himself by pleading his own knowledge, or suggesting that others should respect his

integrity. He can also give, in a subtle way, a warning to those who may be critical of his pronouncements

during the performance.

IV.

The Performer as a Teacher: The Content Of the Ritual

The performer of the ritual utilizes different aspects of the communitys folklore to educate the

community. For example the ritual performer is a chronicler of Babukusu history. Makila (1978) refers to him as

a public historian and comforter. He is a man of great memory, he relies on memorization as he re-enacts

significant historical events that have shaped the destiny of his community. As Nangendo (1994:102) aptly puts

it:

As a major custodian of Babukusu history and traditional culture, he narrates at length about the

coming of Babukusu from their cradle land, how and when Babukusu adopted livestock keeping, subsistence

farming, trading activities, circumcision, metal working, and the traditional concept of the metaphysics, the

meaning of death and reincarnation, interethnic battles and many others.

He further notes that Babukusu keep track of their genealogies through three social institutions, namely

a process called khuswala kumuse, circumcision age sets, and origin traditions (Nangendo 1994:85). Indeed

Vansina (1985) highlights the importance of oral traditions in accounting for the history of a people as

historical sources. For instance, most of baswala Kimise trace the origin of Babukusu community in misri

(Egypt) and also trace the migration of the people to their present settlement. They also mention prominent men

of the past. For that reason, the oratory then can be viewed as a window simultaneously onto the past and

present. It is one of the principle means by which a living relationship with the past is apprehended and

reconstituted in the present.

The orator also refers to issues and experiences whose impact has been relatively recent. This is

because Babukusu society has not remained static over the years. For instance, the performer captures the

imposition of colonial rule and Babukusu resistance, of the independence and new forms of administration. The

performer refers to the chain of command in Kenyas administration-from the village headman up to the

Provincial Commissioner and then to the President of the country.

He also highlights the introduction and spread of western education accompanied with increasing

reliance on written forms of communication. For example the performer talks about use of written form of

communication during dowry negotiations. The number of animals and other items demanded by the brides

people are written on a piece of paper to form the basis of negotiations.

4.1 Didactic Significance

Babukusu used their art as a vehicle of traditional education. Thus during the performance of the ritual,

the oral artist plays a role of a teacher. He gives instructions to the community especially the youth, through

tales, songs, riddles and proverbs. Through these genres of oral literature, the youths were taught moral and

social, historical as well as cultural aspects about their community. He teaches the virtues of hard work; being

honest in their dealings; upholding moral values and shuning laziness, lies, theft, and waywardness. He

counsels, thus:

Okhacha wekhala muchamu ye khukhwiiba bibiindu biabeene ta. Mukhacha kamataala kabeene ta.

Okhakhalakila omwana wowasio niko akhakholile ta, okhachekha batambi, okhachekha bamanani, okhachekha

bayiiya, okhachekha bafuubi.

(Do not sit in the council of evil doers, who plan evil against other people, do not break into other

peoples kraals, do not accuse falsely, do not despise the poor, do not laugh at orphans)

He counsels the youth to shun violence. He uses the metaphor of two young strong elephants that

ventured into the forest. One that was careless and reckless hit its delicate tusk on every tree it came across. In

the end, it broke and destroyed the tusk. The other was careful and cautious and thus kept its tusk safe. The

reckless young elephant stands for a violent youth, who after taking some beer, would fight others for no

apparent reason and would end up in court and finally land in jail. On the other hand, the careful and cautious

elephant stands for calm and peaceful youth who shuns violence and hence is able to co-exist with others hence

prosper. He says that an elephant that is violent cannot nurture its tusk to maturity.

www.iosrjournals.org

36 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

The youths are also taught to respect each other and to respect their elders especially ones father,

mother, grandparents, uncles, aunts and rulers of the land because they have the power to pronounce a curse on

ill-behaved children. The ritual performer also acknowledges the need for the community to change and

embrace formal education and the emerging new technology. He exhorts not only members of his community

to take their children to school, but also all other communities that inhabit the nation of Kenya. He says:

Universiti chili khusibala, secondari chili khusibala, primari chili khusibala. Bakhaloma bali

babukusu sebasomia ta, bakhaloma bali bajaluo sebasomia ta, bakikuyu, bakamba, bameru, sebasomia ta.

(We have many universities, many secondary schools in the country and many primary schools in the

country. Let it not be said that Babukusu did not sent their children to school, let it not be said the Luos, the

Kikuyus, Kambas, Merus, did not sent their children to school)

He correctly argues that in olden days, young men used to raid other communities, so as to amass

wealth. He however points out that in contemporary society, a pen and a book are the effective and efficient

tools to stage a successful raid, be it economic, social or political.

The performer also uses an image of a hunting dog that can sniff its prey and pounce on it. He argues

that a teacher should act as a hunters dog which is endowed with strong scent. For example if one teaches

geography, mathematics, he should sniff deeply into the subject, likewise the students should do the same

hence be able to perform well in their examinations. Oswala kumuse also advocates for girl-child education. He

argues that girls should be educated up to university level to choose careers and participate in the development

of the country and also be able to attract the best suitors. Thus like Ngugi wa Thiongo in The River Between

and Chinua Achebe in Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God, oswala kumuse demonstrates to the young

generation the importance of embracing modernity while retaining the ethical values of traditional Bukusu

community.

The oratory also does engage with social and moral issues of the day that touch on their interests, for

instance the prevalence of HIV/AIDS pandemic. He warns that HIV/AIDS is real and he advises people to stop

engaging in irresponsible sexual behaviour.

4.2 Myths

The ritual oratory addresses a number of mythical phenomena among the babukusu. For example the

mythical origin of babukusu circumcision ritual which is attributed to a man called mango. The myth has it that

khururwe-yabebe was a deadly monstrous serpent that devoured people and their animals. A man called mango

swore to kill the serpent. He sharpened his sword (embalu) and spear (wamachari) until they were razor sharp.

He then took his shield and headed for the serpents abode in the cave.

Mango hid in the darkness of the cave, and when the serpent came back from its days hunt, mango

lashed out a mighty blow and cut off its head. The head flew out and fell against a tree, biting it. It is said that

due to its deadly venom, the tree died up instantly. The people were overwhelmed with joy and gratefulness to

mango. They carried him on their shoulders. Then mango demanded to be circumcised. Mango was

circumcised and started the kolongolo age set. Other men in the community took cue and that is how

circumcision began in the bukusu community.

Another myth associated with circumcision that the performer refers to is sioyaye chant. This song is

sung when the initiate is being escorted from the river (sietosi) to the circumcision ground in front of his fathers

house. The song is sung to signify to the initiate the imminence of the circumcision ceremony. In the song, those

who might fear to face the knife are ridiculed and told they should go to ebunyolo where circumcision is not

practised. The words of this song are said to have been picked from a hyena. It is believed by babukusu that the

song was first sung by a hyena.

Indeed it is argued that many practices are hedged about the myths in order to give them some validity

and universal acceptance amongst the people.

4.3 Politics

Oswala kumuse holds a central role in the politics of his community since his position can be viewed as

a symbol of ethnic unity; his power stems from mystical sources. As such, key personalities especially

politicians seek his blessings before venturing into major enterprises: Such as seeking higher political offices in

the land.

Again, the ritual performer enjoys the venerated role of a seer, prophet, and religious icon; he interprets

the unfolding political scenario and can also prophesize the political future of the community. For instance,

when performing for the late Vice President of Kenya, Kijana Wamalwa, who was also the chairman of FORD

Kenya Party, Manguliech had the following to say:

Luno luri sisiama sia FORD KENYA siarama busa, enja omundu abele nga Wamalwa ache abe

Chairman wa FORD KENYA. Mala omundu oyo nali omulayi, mukhabone busa bamukhola Chairman wa

NARC. Musikari Kombo khekhubolela ewe.

www.iosrjournals.org

37 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

(As for now, FORD Kenya is orphaned. Look for a person, a good person, a person as good as the late

Wamalwa to be the Chairman of Ford Kenya, if that person will be able enough, he will be made the Chairman

of NARC. I am alluding to you Musikari Kombo).

Indeed it came to pass that Musikari Kombo was elected to be the chairman of FORD Kenya party.

Oswala kumuse also enjoys the license to criticize subtly or openly persons in positions of power who pervert

the laws and customs of the nation and laments their abuse of power and neglect of their responsibilities and

obligations to the people. Wanjala (1985:89) captures this aspect when he says, they bemoan the loss of the

true sense of leadership in the present society, and challenge the community not to vote selfish leaders into

parliament.

He challenges members of parliament from his community to represent the interests of their people well, to

serve and help their constituents. He posits:

Ewe Munyasia soyeta

You Munyasia why cant you help.

Ewe Wamalwa Kijana soyeta

You Wamalwa Kijana why cant you help.

Ewe Kapten soyeta

,

You Kapten why cant you help.

Ewe Kituyi soyeta,

You Kituyi why cant you help.

In fulfilling this political function, oswala kumuse bears a striking resemblance to community poets of

other cultures of Africa, ancient Israel, ancient Greece, or medieval Europe.

In fact the Babukusu always feel that oswala kumuses words are representative or reflective of their

interests and aspirations he represents the opinion of those ruled. He interprets, moulds and shapes public

opinion, and he can easily urge them to get warmed up to supporting a certain political stand. Indeed they do

influence voting patterns in their community. He tactfully does not impose his will on the community, but offers

a wise counsel. In criticizing those in authority, the performer serves as a check against abuse of power and

excesses in the community.

Similarly, the oral artist serves as the moral police of the people. He is at liberty to say whatever he

pleases in favour of or against anybody in the community. Indeed, one of the most useful duties performed by

oswala kumuse is to comment sensitively on the evils prevailing in the social or political life of his people. Just

like what modern artists (especially writers) do. A case in point is Soyinka who uses Yoruba mythology as the

basis of his creative work. As Okpewho (1985) notes:

Soyinka himself has done more than any other African writer to make the symbols of traditional

African mythology the basis of his creative work: in various plays , novels and poems , especially his poem

Idanre , he had made the Yoruba god of iron, Ogun, his ideal of the revolutionary artist constantly involved in

the struggle to correct the society.

Consequently, oswala kumuse is sort of the voice of conscience in his community. As a community

poet, he sees the welfare of his people as his own concern and therefore he speaks the truth as he sees it since his

concern is the well-being of the society. He upholds the values of societies in praise and condemns

individualism.

4.4 Economics

Oswala kumuse places a lot of emphasis on the need for the Babukusu to work hard in order to create

wealth for the present and future generations. It is noted that for any society to progress, people must work hard

and use the wealth that they possess prudently. Besides, the traditional society knew this so well and thus the

elders seemed to spend most of their time imparting virtues of hard work. Thus the performer uses proverbs,

allegories and metaphors to pass this message across. A case in point is when he warns men who use their

money and time chasing women. He asserts that one will be condemned to die a pauper once he ties the wealth

of the family (kraal) on his genitals and teeth. He asserts:

Neweenya ofwe ne kumutaambo, obukula litaala wacha wombakha khumeeno, obukule litaala

wombakhe khumakusi, kane ofwe ne kumutambo. Okhabukula litala wombakha Khumeno okhabukula litaala

wombakha khumakusi.

(If you want to die poor, take your kraal and tie it on your teeth.

If you want to die poor, take your kraal and tie it on your genitals!

You will surely die a pauper. Never take your kraal and build it on your teeth, never take your kraal and build it

on your genitals)

He challenges men to be responsible and prudent with the resources at their disposal. At the same time

he warns extravagant women who scatter family wealth using both front and hind legs that they would land their

families into depths of poverty. He says that a hard working woman will lift the social and economic status of

her family.

www.iosrjournals.org

38 | Page

The Context and Structure of Funeral Oratory among the Bukusu

He cautions the members of the community against selling ancestral land and challenges them to invest

in real estate. For example, he exhorts them to invest and put up investment facilities in towns such as

Bungoma and Nairobi. He says that one may travel to America and then boast to his host that Bungoma town or

Nairobi city belongs to them yet he has no share in it. That such would be an empty brocavado in the sense

that one cannot claim to have what he does not own! Again he correctly asserts that it would be foolish for one

to claim ownership over his relatives herd of cattle when he does not own even a single animal. That one needs

to have at least ones own to claim to have a share in it.

The performer acknowledges modern economic practices. He says that when the white man came he

found the Babukusu with five banks in their keep. He argues that he (white man) introduced more powerful

banks which could serve as banks for black man to fight against poverty. These Babukusu banks are,

engokho standati, likhese komasho, embusi paklesi, ekhafu eposita, biakhulia ushirika. (Chicken as the

modern Standard Bank, sheep as the modern Commercial Bank, goat as the modern Barclays Bank, cow for

Posta and food for Ushirika Bank).

Nasimiyu (1991:40) supports this view when she notes that cattle were the traditional bank, the main

form of wealth recognized by Babukusu society as a measurement of wealth and as a status symbol.

4.5 Health

During the performance, oswala kumuse advocates for good health and healthy life styles among his

people. For that reason, he exhorts his community to grow and consume indigenous foods such as millet,

sorghum, cowpeas, namasaka, murere, beans, mureenda, chisaaka, and fish, and to consume less of sugary foods

such as cakes, and bread, that are harmful to their health. He laments that people are dying young because of

poor eating habits consuming foods high in saturated fats and high in calories. Again it is a medical reality

that diseases such as coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes, stroke, hypertension and alcohol induced liver

cirrhosis are on increase due to poor eating habits.

In contemporary Bukusu society, like many other communities in Kenya and the world over, the issue

of AIDS and HIV pandemic is of major concern. The Aids scourge has killed millions upon millions of people

in the world, destroyed families and reversed economic gains in many communities of the world. Oswala

kumuse in his oration uses the image of a tree called kumunandere to warn his audience to take care. He asserts

that, an individual who gets involved in behavioral activities that can expose him to the risk of being infected is

the one who is likely to contract the virus. He counsels the community to be careful because Aids is real. He

says, mwichunge, sibala engara (be careful, the world is round). The performer also uses the image of a salt

lick to illustrate the mode of transmission of HIV/AIDS virus. He rightly points out that he/she who licks

gets infected.

V.

Conclusion

In a nutshell the performer parades historical events of the Babukusu in terms of economic and social

changes, wars conquests and rebellion. In so doing, he provides his community with a mirror for self

examination. Morever, the past is very important in shaping identities, in defining the present as well as charting

the future.

References

[1].

[2].

[3].

[4].

[5].

[6].

[7].

[8].

[9].

[10].

[11].

[12].

[13].

Amuka Peter (1992) The play of Deconstruction in the Speech of Africa: Pankruok and

Ngero in Telling Culture in Dholuo. In Reflections of Theories and Methods in Oral Literature. Nairobi: KOLA.

Kunene. M. (1981). Anthem of the Decates. Nairobi: Heinemann Educational Decades Books

Ltd.

Makila, F. E. (1978). An Outline History of the Bukusu. Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau.

Nangendo, S.M. (1994). Daughters of the clay, Women of the Farm: Women, Agricultural

Economic Development, and Ceremic Production in Bungoma District,WesternProvince in Kenya. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Bryn

Mawr College.

Nasimiyu, R. (1991). Women and Childrens labour in rural ecomony: A case Study of Western Province Kenya, 1902 1985.

Unpublished PhD Thesis Dalhousie University.

Odhiambo,C.J.(2006). From Siwidhe to Theatre Space: Paradigm Shifts in the Performance of Oral Narratives in Kenya. In

Nairobi journal of Literature. Nairobi:KOLA. (Pg 126).

Okombo, O. and Nandwa, J. (ed.)(1992). Reflections on Theories and methods in Oral Literature. Nairobi: KOLA.

Okpewho, I. (1985) (ed.). The Heritage of African Poetry. London:Longman

Okot, P. (1972). Song of Lawino. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers Ltd.

Soyinka,W. (1976). Myth Literature and African World. Cambridge University Press.

Turner, V. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. London: Cornell University Press.

Wanjala, C. (1985). Twilight years are years of counsel and wisdom in History and Culture In Western Kenya. The People of

Bungoma district through Time. (Ed) S.

www.iosrjournals.org

39 | Page

Você também pode gostar

- Art 2017 Lekan Balogun - Diaspora Theater andDocumento14 páginasArt 2017 Lekan Balogun - Diaspora Theater andVinícius Ribeiro Castelo BrancoAinda não há avaliações

- Sounds of Other Shores: The Musical Poetics of Identity on Kenya's Swahili CoastNo EverandSounds of Other Shores: The Musical Poetics of Identity on Kenya's Swahili CoastAinda não há avaliações

- Nigerian LiteratureDocumento7 páginasNigerian LiteratureIbraheem Muazzam Ibraheem FuntuaAinda não há avaliações

- From Orality To Print: An Oraliterary Examination of Efua T. Sutherland'S The Marriage of Anansewa and Femi Osofisan'SDocumento6 páginasFrom Orality To Print: An Oraliterary Examination of Efua T. Sutherland'S The Marriage of Anansewa and Femi Osofisan'SOwusu IsaacAinda não há avaliações

- Divining The PastDocumento33 páginasDivining The Pastisola511Ainda não há avaliações

- Awka Journal of ResearchDocumento11 páginasAwka Journal of Researchtekaruth04Ainda não há avaliações

- Meaning and Communication in Yoruba MusicDocumento6 páginasMeaning and Communication in Yoruba MusicWalter N. Ramirez100% (1)

- Abstract BookDocumento118 páginasAbstract BookMd Intaj AliAinda não há avaliações

- Folk Hero Through Oral NarrativesDocumento21 páginasFolk Hero Through Oral NarrativesBhogi ChamlingAinda não há avaliações

- Art Theory 2 PaperDocumento21 páginasArt Theory 2 PaperIvan IyerAinda não há avaliações

- Book Reviews: Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's ZaireDocumento3 páginasBook Reviews: Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's ZairegpnasdemsulselAinda não há avaliações

- Notes Other PapersDocumento3 páginasNotes Other Papersbubba997Ainda não há avaliações

- Rediscovering The Literary Forms of Surigao: A Collection of Legends, Riddles, Sayings, Songs and PoetryDocumento19 páginasRediscovering The Literary Forms of Surigao: A Collection of Legends, Riddles, Sayings, Songs and PoetryPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Muller LDancinggoldenstoolsDocumento27 páginasMuller LDancinggoldenstoolsudehgideon975Ainda não há avaliações

- Why Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology ofDocumento3 páginasWhy Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology ofTIKA RUSSALISAinda não há avaliações

- Selected Papers On Music in Sabah by Jacqueline Pugh-KitinganDocumento5 páginasSelected Papers On Music in Sabah by Jacqueline Pugh-KitinganctjphebeAinda não há avaliações

- Asm 26 15Documento45 páginasAsm 26 15mohamed abdirahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of African Cultural StudiesDocumento14 páginasTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of African Cultural StudiesJosy CutrimAinda não há avaliações

- History From Below A Case Study of Folklore in TulunaduDocumento8 páginasHistory From Below A Case Study of Folklore in TulunaduMarcello AssunçãoAinda não há avaliações

- Yoruba Folktales and The New MediaDocumento14 páginasYoruba Folktales and The New Mediaajibade ademolaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter One 1.0 Background of The StudyDocumento21 páginasChapter One 1.0 Background of The StudyOnifade Oluwatoowo Lydia67% (3)

- Afro Brazilian MusicDocumento45 páginasAfro Brazilian MusicKywza FidelesAinda não há avaliações

- Why Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology of PDFDocumento3 páginasWhy Suya Sing A Musical Anthropology of PDFAndréAinda não há avaliações

- FolkloreDocumento2 páginasFolkloreKeannu EstoconingAinda não há avaliações

- Indigenous Music in A New RoleDocumento20 páginasIndigenous Music in A New RoleTine AquinoAinda não há avaliações

- Mapenzi: A Philosophical Interpretation of The Significance of Oral Forms in I. Mabasa's Novel (1999)Documento24 páginasMapenzi: A Philosophical Interpretation of The Significance of Oral Forms in I. Mabasa's Novel (1999)IsmailAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology of The Perception of Kazakh Musical Epics - by Alma KunanbaevaDocumento6 páginasPsychology of The Perception of Kazakh Musical Epics - by Alma KunanbaevaadaletyaAinda não há avaliações

- Komunitas: Javanese Language and Culture in The Expression ofDocumento10 páginasKomunitas: Javanese Language and Culture in The Expression oftino pawAinda não há avaliações

- Etudesafricaines 4631Documento26 páginasEtudesafricaines 4631Gervins EtokoAinda não há avaliações

- Lalon's PhilosophyDocumento20 páginasLalon's PhilosophyAtri Deb ChowdhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Epic Tradition in TuluDocumento10 páginasEpic Tradition in TuluGabriel VastoAinda não há avaliações

- Epics in The Oral Genre System of Tulunadu: B. A. Viveka RaiDocumento10 páginasEpics in The Oral Genre System of Tulunadu: B. A. Viveka RaisatyabashaAinda não há avaliações

- Week 1 - Introduction No VidsDocumento25 páginasWeek 1 - Introduction No VidsMind TwisterAinda não há avaliações

- Research PaperDocumento21 páginasResearch Paperapi-538791689Ainda não há avaliações

- Figurative Language and Symbolism Manifested in BuDocumento9 páginasFigurative Language and Symbolism Manifested in BuJuma JairoAinda não há avaliações

- Steven L. Riep - EN - Representations of Blindness and Visual Disabilities in China: An Historical OverviewDocumento18 páginasSteven L. Riep - EN - Representations of Blindness and Visual Disabilities in China: An Historical OverviewFondation Singer-PolignacAinda não há avaliações

- Research Project Final DraftDocumento17 páginasResearch Project Final Draftapi-662034787Ainda não há avaliações

- African Oral Literature and Modern African Drama: Inseparable NexusDocumento8 páginasAfrican Oral Literature and Modern African Drama: Inseparable NexusAkpevweOghene PeaceAinda não há avaliações

- Ajibade, G .2007. New Wine in Old Cups. Postcolonial...Documento23 páginasAjibade, G .2007. New Wine in Old Cups. Postcolonial...sanchezmeladoAinda não há avaliações

- Confucius On MusicDocumento26 páginasConfucius On MusicChanon AdsanathamAinda não há avaliações

- HISKI ACEH (English) - Revisi TomDocumento13 páginasHISKI ACEH (English) - Revisi TomndreimanAinda não há avaliações

- The Sutra of Druma, King of The Kinnara and The Buddhist Philosophy of MusicDocumento18 páginasThe Sutra of Druma, King of The Kinnara and The Buddhist Philosophy of MusicRavanan AmbedkarAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Creations of The Uzbek People and Their SignificanceDocumento4 páginasOral Creations of The Uzbek People and Their SignificanceCentral Asian StudiesAinda não há avaliações

- Bakonjo DanceDocumento16 páginasBakonjo DanceerokuAinda não há avaliações

- A Kiranti-Kõits EthnographyDocumento38 páginasA Kiranti-Kõits EthnographyDr Lal-Shyãkarelu Rapacha100% (1)

- Guramayle ( Black Crow'), But Also The Sounds Of: SRC.: Dirk Bustorf's Fi Eld Notes From Gurage, SélteDocumento5 páginasGuramayle ( Black Crow'), But Also The Sounds Of: SRC.: Dirk Bustorf's Fi Eld Notes From Gurage, SélteMenab AliAinda não há avaliações

- Widdes - Music Meaning and CultureDocumento8 páginasWiddes - Music Meaning and CultureUserMotMooAinda não há avaliações

- Modern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideDocumento3 páginasModern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideHanisahAinda não há avaliações

- Modern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideDocumento3 páginasModern African Literature and Cultural Identity: Tanure OjaideHanisahAinda não há avaliações

- Franchetto2010 Biography PDFDocumento40 páginasFranchetto2010 Biography PDFJoaolmpAinda não há avaliações

- Musical Imagination of Emptiness' in Contemporary Buddhism-Related MusicDocumento22 páginasMusical Imagination of Emptiness' in Contemporary Buddhism-Related MusicO.W. ChowAinda não há avaliações

- Pyer Pereira TianaDocumento36 páginasPyer Pereira TianaRegz GasparAinda não há avaliações

- RitualAndRitualization EllenDissanayakeDocumento24 páginasRitualAndRitualization EllenDissanayakeTamara MontenegroAinda não há avaliações

- Frost PoetryDocumento20 páginasFrost PoetryishikaAinda não há avaliações

- The Potter and The Clay: Folklore in Gender Socialisation: Department of LanguagesDocumento20 páginasThe Potter and The Clay: Folklore in Gender Socialisation: Department of LanguagesApoorv TripathiAinda não há avaliações

- Songs of The Bauls Voices From The Margins As Tran PDFDocumento19 páginasSongs of The Bauls Voices From The Margins As Tran PDFPritha ChakrabartiAinda não há avaliações

- Webb Keane - The Spoken HouseDocumento24 páginasWebb Keane - The Spoken HousemozdamozdaAinda não há avaliações

- AlaturkaDocumento30 páginasAlaturkaOkan Murat Öztürk100% (1)

- TheatreDocumento8 páginasTheatreSugar BambiAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of Formative Assessment On Mathematics Test Anxiety and Performance of Senior Secondary School Students in Jos, NigeriaDocumento10 páginasEffects of Formative Assessment On Mathematics Test Anxiety and Performance of Senior Secondary School Students in Jos, NigeriaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Students' Perceptions of Grammar Teaching and Learning in English Language Classrooms in LibyaDocumento6 páginasStudents' Perceptions of Grammar Teaching and Learning in English Language Classrooms in LibyaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Study The Changes in Al-Ahwaz Marshal Using Principal Component Analysis and Classification TechniqueDocumento9 páginasStudy The Changes in Al-Ahwaz Marshal Using Principal Component Analysis and Classification TechniqueInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Instructional Methods and Locus of Control On Students' Speaking Ability (An Experimental Study in State Senior High School 01, Cibinong Bogor, West Java)Documento11 páginasThe Effect of Instructional Methods and Locus of Control On Students' Speaking Ability (An Experimental Study in State Senior High School 01, Cibinong Bogor, West Java)International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Project Based Learning Tools Development On Salt Hydrolysis Materials Through Scientific ApproachDocumento5 páginasProject Based Learning Tools Development On Salt Hydrolysis Materials Through Scientific ApproachInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Enhancing Pupils' Knowledge of Mathematical Concepts Through Game and PoemDocumento7 páginasEnhancing Pupils' Knowledge of Mathematical Concepts Through Game and PoemInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Philosophical Analysis of The Theories of Punishment in The Context of Nigerian Educational SystemDocumento6 páginasPhilosophical Analysis of The Theories of Punishment in The Context of Nigerian Educational SystemInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Necessary Evils of Private Tuition: A Case StudyDocumento6 páginasNecessary Evils of Private Tuition: A Case StudyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Need of Non - Technical Content in Engineering EducationDocumento3 páginasNeed of Non - Technical Content in Engineering EducationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Development of Dacum As Identification Technique On Job Competence Based-Curriculum in High Vocational EducationDocumento5 páginasDevelopment of Dacum As Identification Technique On Job Competence Based-Curriculum in High Vocational EducationInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Child Mortality Among Teenage Mothers in OJU MetropolisDocumento6 páginasChild Mortality Among Teenage Mothers in OJU MetropolisInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Youth Entrepreneurship: Opportunities and Challenges in IndiaDocumento5 páginasYouth Entrepreneurship: Opportunities and Challenges in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)100% (1)

- Comparison of Selected Anthropometric and Physical Fitness Variables Between Offencive and Defencive Players of Kho-KhoDocumento2 páginasComparison of Selected Anthropometric and Physical Fitness Variables Between Offencive and Defencive Players of Kho-KhoInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Geohydrological Study of Weathered Basement Aquifers in Oban Massif and Environs Southeastern Nigeria: Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System TechniquesDocumento14 páginasGeohydrological Study of Weathered Basement Aquifers in Oban Massif and Environs Southeastern Nigeria: Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System TechniquesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Advancing Statistical Education Using Technology and Mobile DevicesDocumento9 páginasAdvancing Statistical Education Using Technology and Mobile DevicesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Application of Xylanase Produced by Bacillus Megaterium in Saccharification, Juice Clarification and Oil Extraction From Jatropha Seed KernelDocumento8 páginasApplication of Xylanase Produced by Bacillus Megaterium in Saccharification, Juice Clarification and Oil Extraction From Jatropha Seed KernelInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Microencapsulation For Textile FinishingDocumento4 páginasMicroencapsulation For Textile FinishingInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Psychological Variables Within Different Positions of Players of The State Junior Boys Ball Badminton Players of ManipurDocumento4 páginasComparison of Psychological Variables Within Different Positions of Players of The State Junior Boys Ball Badminton Players of ManipurInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Explosive Strength Between Football and Volley Ball Players of Jamboni BlockDocumento2 páginasComparison of Explosive Strength Between Football and Volley Ball Players of Jamboni BlockInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Study of Effect of Rotor Speed, Combing-Roll Speed and Type of Recycled Waste On Rotor Yarn Quality Using Response Surface MethodologyDocumento9 páginasStudy of Effect of Rotor Speed, Combing-Roll Speed and Type of Recycled Waste On Rotor Yarn Quality Using Response Surface MethodologyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Core Components of The Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcohlic Fatty Liver DiseaseDocumento5 páginasCore Components of The Metabolic Syndrome in Nonalcohlic Fatty Liver DiseaseInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Lipoproteins and Lipid Peroxidation in Thyroid DisordersDocumento6 páginasLipoproteins and Lipid Peroxidation in Thyroid DisordersInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Comparative Effect of Daily Administration of Allium Sativum and Allium Cepa Extracts On Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsDocumento6 páginasComparative Effect of Daily Administration of Allium Sativum and Allium Cepa Extracts On Alloxan Induced Diabetic RatsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Success of Construction ProjectDocumento10 páginasFactors Affecting Success of Construction ProjectInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Analysis On Sustainability Opportunities and Challenges of Bio-Fuels Industry in IndiaDocumento7 páginasResearch Analysis On Sustainability Opportunities and Challenges of Bio-Fuels Industry in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Auxin Induced Germination and Plantlet Regeneration Via Rhizome Section Culture in Spiranthes Sinensis (Pers.) Ames: A Vulnerable Medicinal Orchid of Kashmir HimalayaDocumento4 páginasAuxin Induced Germination and Plantlet Regeneration Via Rhizome Section Culture in Spiranthes Sinensis (Pers.) Ames: A Vulnerable Medicinal Orchid of Kashmir HimalayaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- A Review On Refrigerants, and Effects On Global Warming For Making Green EnvironmentDocumento4 páginasA Review On Refrigerants, and Effects On Global Warming For Making Green EnvironmentInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Investigation of Wear Loss in Aluminium Silicon Carbide Mica Hybrid Metal Matrix CompositeDocumento5 páginasInvestigation of Wear Loss in Aluminium Silicon Carbide Mica Hybrid Metal Matrix CompositeInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Parametric Optimization of Single Cylinder Diesel Engine For Specific Fuel Consumption Using Palm Seed Oil As A BlendDocumento6 páginasParametric Optimization of Single Cylinder Diesel Engine For Specific Fuel Consumption Using Palm Seed Oil As A BlendInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Week 2Documento4 páginasWeek 2Greely Mae GumunotAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Updated 1Documento99 páginasLiterature Updated 1Jocelyn TabelonAinda não há avaliações

- Character Poem Model Abandoned Farmhouse and InstructionsDocumento2 páginasCharacter Poem Model Abandoned Farmhouse and InstructionslaurakmetzAinda não há avaliações

- 21st Century Literary GenresDocumento23 páginas21st Century Literary GenresKlint BryanAinda não há avaliações

- Uk Quals Gcse English Gcse 1203 66800Documento5 páginasUk Quals Gcse English Gcse 1203 66800seyka4Ainda não há avaliações

- English Literature 0475 TheoryDocumento27 páginasEnglish Literature 0475 TheoryAlyssa WongAinda não há avaliações

- The Language Letters - Selected - Matthew HoferDocumento441 páginasThe Language Letters - Selected - Matthew HoferSantiago Erazo100% (5)

- Verse and Drama Unit 1-5Documento23 páginasVerse and Drama Unit 1-5Ramzi JamalAinda não há avaliações

- Week-2 Humss006 HandoutDocumento6 páginasWeek-2 Humss006 HandoutFrancine Mae HuyaAinda não há avaliações

- Growing Minds Mar 2013Documento124 páginasGrowing Minds Mar 2013Parthapratim MaliAinda não há avaliações

- G11 - Q1 - Mod4 - Sample Oral CommunicationDocumento11 páginasG11 - Q1 - Mod4 - Sample Oral CommunicationZerhan Laarin100% (2)

- Saddlebrook Preparatory School: Curriculum Map-Scope and Sequence: Grade 12 EnglishDocumento18 páginasSaddlebrook Preparatory School: Curriculum Map-Scope and Sequence: Grade 12 EnglishYbañez MercAinda não há avaliações

- Inventory of Available Learning Resource Material: Learning Area Quarter Most Essential Learning Competency Grade LevelDocumento4 páginasInventory of Available Learning Resource Material: Learning Area Quarter Most Essential Learning Competency Grade LevelzsaraAinda não há avaliações

- Al Farabi Book of LettersDocumento27 páginasAl Farabi Book of LettersAdrian Mucileanu100% (1)

- Teaching Guide 21st Century LitDocumento7 páginasTeaching Guide 21st Century LitMary Joan PenosaAinda não há avaliações

- KahlschlagDocumento4 páginasKahlschlagRuth Calvo IzazagaAinda não há avaliações

- The Living PhotographDocumento3 páginasThe Living PhotographAfiq NaimAinda não há avaliações

- Proceedings of Classical Association Vol. 17Documento172 páginasProceedings of Classical Association Vol. 17pharetimaAinda não há avaliações

- B.A English PDFDocumento28 páginasB.A English PDFSethu100% (1)

- The Aged MotherDocumento3 páginasThe Aged MotherNicole GuillermoAinda não há avaliações

- SHSA1107Documento181 páginasSHSA1107Abhay SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Creative Writing - 2ndQ ExamDocumento6 páginasCreative Writing - 2ndQ ExamKristine Bernadette Martinez100% (1)

- 21st Century 1st Quarter Exam 2019 - CourseheroDocumento4 páginas21st Century 1st Quarter Exam 2019 - CourseheroMilky De Mesa ManiacupAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Note English Studies For JSS 1 Second TermDocumento1 páginaLesson Note English Studies For JSS 1 Second Termugbechieedmund073Ainda não há avaliações

- Group A Project (The Fisher Man Invocation) - 1Documento14 páginasGroup A Project (The Fisher Man Invocation) - 1chiomajoanna79Ainda não há avaliações

- Innovative Lesson PlanDocumento15 páginasInnovative Lesson PlanAmmu Nair G MAinda não há avaliações

- O Wild West Wind, Thou Breath of Autumn's BeingDocumento6 páginasO Wild West Wind, Thou Breath of Autumn's BeingadrianoAinda não há avaliações

- Shelley ImageryDocumento13 páginasShelley ImageryChiara FenechAinda não há avaliações

- Soal PGSD Bahasa Inggris 20 20 Ganjil SanthiDocumento5 páginasSoal PGSD Bahasa Inggris 20 20 Ganjil Santhisanipung2011Ainda não há avaliações

- Summative Assessment 2.3Documento2 páginasSummative Assessment 2.3John Mark MatibagAinda não há avaliações

- The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartNo EverandThe Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America ApartAinda não há avaliações

- Be a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooNo EverandBe a Revolution: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,No EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (69)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyNo EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (18)

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaNo EverandWhen and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (33)

- Something Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleNo EverandSomething Must Be Done About Prince Edward County: A Family, a Virginia Town, a Civil Rights BattleNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (34)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesNo EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (70)

- White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraNo EverandWhite Guilt: How Blacks and Whites Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights EraNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (43)

- Say It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyNo EverandSay It Louder!: Black Voters, White Narratives, and Saving Our DemocracyAinda não há avaliações

- Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaNo EverandShifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (10)

- Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyNo EverandRiot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its LegacyNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (13)

- The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeNo EverandThe Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave TradeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedNo EverandPlease Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to SucceedNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (154)

- Black Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritNo EverandBlack Fatigue: How Racism Erodes the Mind, Body, and SpiritNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (83)

- Summary of Coleman Hughes's The End of Race PoliticsNo EverandSummary of Coleman Hughes's The End of Race PoliticsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Decolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeNo EverandDecolonizing Therapy: Oppression, Historical Trauma, and Politicizing Your PracticeAinda não há avaliações

- Walk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphNo EverandWalk Through Fire: A memoir of love, loss, and triumphNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (72)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageNo EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (82)