Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

American - Pastoral Commento

Enviado por

Eric GarciaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

American - Pastoral Commento

Enviado por

Eric GarciaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nothing is impersonally

perceived: Dreams, Realistic

Chronicles and Perspectival

Effects in American Pastoral

Pia Masiero

Universit Ca Foscari Venezia

American Pastoral is a rather complex novel. Each time I teach it, I get the same

response: Roths Pulitzer winning book is a great book, but it is difficult to put

together. The single most baffling item listed by my students when pressed to

articulate what makes it complex concerns the disappearance of the first-person

pronoun. In other words, where is Zuckerman, the presiding consciousness of the

first eighty-odd pages? Why does he not return to wrap up the Swedes story?

What follows will address these questions and try to illuminate the narratological issues at stake in Roths masterpiece: I firmly believe that the experiential

conditions of readers (Toolan, Irresponsibility 265) are the backdrop against

which to measure any critical endeavor.

Narratologically speaking, American Pastoral can be divided in two clear-cut

sections. In the first one, ending on page 89, the reader is confronted with Philip

Roths most cherished characterNathan Zuckermanwho speaks in his own

voice using the first person pronoun. From page 90 up to the very end of the book

the first-person account gives way to a third-person narrative strictly focalized on

Seymour Levovthe Swedewe have come to know through Zuckermans own

recollections of his childhood years.

Thus stated, the narratological structure would seem clear enough. And yet,

once we try to define the precise contours of this second (so to speak) section and

its relation to the first, numerous questions arise.

First of all, the pivotal referential shift characterizing the novel is not visually

emphasized by a chapter break. A cursory look at the book contents page, in fact,

suggests that American Pastoral is the story of an apparently seamless trajectory detailing the recollection of a situation of harmony (Paradise Remembered)

followed by a disruption (The Fall) and the consequent awareness of a loss

(Paradise Lost). The only possible hint at a change in perspectival gear depends

179

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 179

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

on making the most out of the specification remembered which in itself implies

a remembering subject. And yet, there is no way of distinguishing this recollecting subject from the one who falls and loses a previously idyllic life. Differently

put, the reader is tricked into believing that the book is made up of three sections

(harmoniously made up of three chapters each) related by echoing titles. Well, obviously enough, the book is made up of three sections which nonetheless are only

apparently reader friendly: thematic development notwithstanding, these titles

do not mark in any way the dramatic change in perspective1 defining the narratological structure of the book.2 I suggest that burying the cut dividing the book

in two clearly distinguishable narratological halves in the middle of the chapter

which closes section one (Paradise Remembered) may be taken to be an objective correlative of the strategy of disguise Roth via Zuckerman is a master of.

What has been buried, in fact, is not so much the narrative shift from first to third

person which is visible enough, but the originating source of the presentation of

the Swedes consciousness, namely Zuckermans inventiveness.

The key to understanding American Pastoral is contained in the transition between the two focalizing modes: thus, the high school reunion is the place where

one can start to grasp the relationship between them. Not only does the shift take

place while Zuckerman is dancing with Joy Helpern, but we are explicitly invited to consider the whole book we are reading as originating there. The news

Zuckerman receives from the Swedes brother Jerry, in fact, sets the writers mind

in motion and the result of Zuckermans immersion is the as-yet untitled manuscript of American Pastoral.3 Significantly, the paragraph immediately following

Jerrys bare essentials details the months to come in which Zuckerman think[s]

about the Swede for six, eight, sometimes ten hours at a stretch [] inhabit[s] this

person least like [himself], disappear[s] into him, day and night [tries] to take the

measure of a person of apparent blankness and innocence and simplicity, chart

his collapse (74).

This three-page-long section interrupts the high-school reunion opening a proleptical window on Zuckermans creative period: the writer tells us about the

end of his obsessive absorption and its result, the actual completion of his manuscript. Considering the level of the story, American Pastoral cannot be identified

as a framed narrative; once we take into account the level of discourse, however,

these pages provide the closing of the frame we will not get where we would

1I prefer to use the term perspective because it can be associated both to point of view and to opinion.

2There is another significant detail going in the same (not-reader-friendly) direction: the account of Sept 1, 1973 coincides with the beginning of chapter five, which is the middle chapter of section two (The Fall). The obvious result

is that the account of that eventful day oversteps the boundaries of the section diffusing the perception of its unity.

3For an analysis concerning the books (possibly) written by Nathan Zuckerman in his whole career see my Philip

Roth and the Zuckerman Books, pp. 207-212.

180

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 180

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

expect (and would like) it to be, namely, at the end of the book. No wonder that

buried as it is in the middle of a very emotionally intense scene, the closing of the

frame ends up forgotten exactly like the spelling out of the source of the Swedes

presentation. In the whole book, there is just one other reference to writing this

book, liable like this one to be read and forgotten (more about this later). After this

crucial meta-narrative asideparaphrasing Zuckermans own words, this is as

far as we get, as much of a framing earful as we are to hear from the narratorwe

are plunged back into the high-school reunion. We already know that the Swede

and his family came to life in [Zuckerman] (77; my italics) through a work based

on sorting out aesthetically relevant facts4 and providing the missing links, but

we will now be given important clues to understand the directions this making

up will take. The shift in focalizationadumbrated in Zuckermans using two

highly significant verbs (inhabiting and disappearing)is carefully prepared and

explained. We are shown into Zuckermans mind and accompanied in his progressive involvement in a perspective different from his own.

Zuckerman is dancing with Joy and cannot help thinking about the Swede and

trying to make ends fit: the image of the smiling Swede at the Shea Stadium, the

uneventful dinner at Vincents and the news he has just received from his brother.

Zuckerman begins imperceptibly to do his jobinventing sense-making stories

and stories that make (narrative) sense. The sense depends crucially on imagining thoughts appropriate to the kind of person the Swede was. While Jerry was

still talking and showering his opinions about his brother on him, Zuckerman

had already wondered: righteous anger at the daughter? No doubt that would

have helped. [] But given the circumstances, wasnt it asking a lot, asking the

Swede to overstep the limits that made him identifiably the Swede? (72). The

story Zuckerman wants to tell and is already beginning to weave while dancing

with Joy has to be identifiably the Swedes in spite of its coming from his own

imaginative work. Or, to be more precise, his imaginative work has to revolve

around a strictly mimetic ingredient. The famous writer begins sliding toward his

heros point of view, putting forward what he believes to be the foundation of the

Swedes existential predicament: I was thinking again of the Swede [] a man

[] awakening in middle age to the horror of self-reflection (85).

Zuckerman begins to contemplate the very thing that must have baffled the

Swede till the moment he died: how had he become historys plaything? (87) after repeating to himself the very words Jerry told him:

4Of course I was working with traces; of course essentials of what he was to Jerry were gone, expunged from my

portrait, things I was ignorant of or I didnt want [] (76; my italics).

181

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 181

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

He kept peering in from outside at his own life. The struggle of his life was to bury

this thing. But how could he? Never in his life had occasion to ask himself, Why are

things the way they are? Why should he bother, when the way they were was always

perfect? Why are things the way they are? The question to which there is no answer,

and up till then he was so blessed he didnt even know the question existed. (87; emphasis in original)

The verbatim repetition has an incantatory quality: Zuckerman rehearses the tenets around which his imaginative foray must revolvethe facts on which his fiction has to be foundedand plunges into a third-person narrative. The contemplation thus is not tentative, but bears a necessity both existentially authentic and

narratively tenable. Zuckermans search for the right key to access the Swedes

horrendous self-reflection is as sharp as a surgical knife: I began to try to work

out for myself what exactly had shaped a destiny unlike any imagined for the famous Weequahic three-letterman (87; my italics).

Hed invoked in me, when I was a boy [] the strongest fantasy I had of being someone else. But to wish oneself into anothers glory, as boy or as man,

is an impossibility, untenable on psychological grounds if you are not a writer, and on aesthetic grounds if you are. To embrace your hero in his destruction, howeverto let your heros life occur within you when everything is

trying to diminish him, to imagine yourself into his bad luck, to implicate

yourself [] in the bewilderment of his tragic fallwell, thats worth thinking about. (88)

Zuckerman is not only detailing how it is the news of the Swedes destruction that

renders him a possible subject for the writers mind, he is reflecting about the narratological structure he deems worth thinking about. The terms Zuckerman uses

here are crucial and foundational: the writer becomes the Swede letting his life occur within him, implicating himself in the bewilderment of his tragic fall. This specification adds to the basic concept of choosing a specific perspective, the further,

second-order layer of imagining his hero reflecting about himself. Zuckermans

portrait of the Swede centers on his imagining the Swedes own facing his predicament starting, as we have seen, from what is identifiably the Swedes. The reader

can judge the plausibility of the language and the perspective Zuckerman will

present thanks to the long immersion in the mystique of the Swede s/he has been

exposed to in the first section: the paradise Zuckerman remembers functions

as the necessary premise to measure the internal verisimilitude of Zuckermans

story.

182

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 182

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

I am thinking of the Swedes great fall and of how he must have imagined

that it was founded on some failure of his responsibility. There is where it

must begin. It doesnt matter if he was the cause of anything. He makes himself responsible anyway. [] Yes, the cause of the disaster has for him to be a

transgression. How else would the Swede explain it to himself? It has to be a

transgression, a single transgression, even if it is only he who identifies it as

a transgression. The disaster that befalls him begins in a failure of his responsibility, as he imagines it. (89; emphasis in original)

This paragraph precedes the shift in focalization and shows the writers mind circling around a (narrative) target which gets closer and more convincing: his contemplation has found some key termsfailure, responsibility, transgression

mingled with the modal must (and its variant has to) and the verb imagine, all

repeated again and again. The core of the narrative logic Zuckerman is sure he has

found (Yes, we hear the writer say) is highlighted with italics: as he imagines it

condenses in a sentence the figural strategy Zuckerman has come up with. The

discourse will emanate from the focalized consciousness of the reflector character as a result of Zuckermans illusionistic narrative technique (Fludernik 344).

So far, we have been close-reading the high-school reunion scene as it is pivotal to understand Zuckermans eminently figural project. The Swede is lifted on

Zuckermans stage5 through the spelling out of the magic words I dreamed a

realistic chronicle (89). Each of these words helps delimit the framework of the

subsequent narrative, condensing synthetically what Zuckerman has been reflecting upon during the reunion. The writers I is the uncontested source of the

presentation of the Swedes consciousness; the Swede comes to life in his imagination, but this dream will look like a chronicle reporting the inner occurrences

of an individual consciousness. The indeterminate article a confirms indirectly

that this is Zuckermans version of the Swede and, that there may be alternative

versions characterized by different slants and/or omissions.

When Zuckerman invokes the generic frame of a realistic chronicle, it is in order to diffuse the association with pure fantasy the verb to dream is liable to trigger. We should not forget that in the meta-narrative aside proleptically showing

Zuckerman past his Swedish immersion, the writer advocates for his fiction a

truth comparable to Jerrys (and just as disputable as his) (76-77). The concept

of distortion inherently contained in the semantic field of dreaming is here both

5It is worth stressing that the generic I lifted the Swede up onto the stage (88) becomes in the paragraph containing the shift in focalization I lifted onto my stage the boy we were all going to follow into America (89). The sentence condenses in itself the tenets of Zuckermans endeavor: 1. Zuckerman is the one who lifts the Swede onto his

stage (everything begins and ends in Zuckermans agency as a writer). 2. The one on the stage is the Swede, he is the

one who occupies the center (restricted internal focalization). See also Masiero 145-152.

183

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 183

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

confirmed and redirected toward the notion that an undistorted account of events

simply does not exist. Zuckerman defends his fiction of the Swede on the basis of

the method he has applied: rigorous research on the field (trips, photos, pictures,

microfilmed sport pages, books) and a consequent mimetic adherence to what he

is sure to be identifiably the Swedes.

The new pattern of focalization could be taken as an exemplary instance of

Zuckermans commitment to Roths ventriloquist passion. It can in fact be understood as a masterful handling of two voicesZuckermans voice as narrator

(focalizing on the Swede) in the background and the voice we perceive as coming

from the Swede (focalization through the character) in the foreground.6

Posing Zuckerman as the author of American Pastoral directs our attention to the

originary presence and voice (the writers) providing the anchoring for another

differentvoice (the Swedes). The explicit spelling out of the source of all textual

utterancesZuckermanoffers the readers a viable way to naturalize7 the tonal

quality of the text. As a ventriloquist, Zuckerman must convincingly sustain the

illusion of the Swedes recognizably individual and specific voice while letting us

hear his own voice. The pleasure is precisely in the throwing [] of voices rather than in any final fixing of their source. The act of ventriloquism problematizes

presence. But it does so by staging presence (Aczel, Commentary 704-705). In

less metaphorical words, FID [the most obviously ventriloquist device] is constituted in the perceived difference of voice in the FID utterance from the voice of the

broader utterance in which it is embedded (Aczel, Hearing 478).

How do these two voices and perspectives interact concretely?

The second section of Roths novel seems to fit well Stanzels description of a

figural narrative (even if not, as we shall see, prototypically) revolving around the

interplay between a mediating voice and the point of view that voice mediatesa

distinction well describing what we might provisionally call Zuckermans audibility and the Swedes visibility. This latter is best understood through the notion

of strict focalization. The second half of the book is, in fact, firmly locked in a

deictic center determining the specific spatio-temporal coordinates of the Swedes

obsessive probing at the ungraspable reasons of his stupendous fall. This anchoring is associated with a singulative frequency mode and the presentation of events

in scenic sequence; the Swede is furthermore rendered visible by the whole panoply of what Jahn calls criterial features of focalization (Windows 243): the

6Even if I understand Fluderniks attacking the distinction between voice and focalization (New Wine 634-635),

I would argue that we gain a notable heuristic pay-off in conceiving American Pastoral as built around this basic

structure: Zuckerman tells what (he thinks) the Swede perceives either in the Swedes voice or in his own (or both).

7Naturalization may be described as the automatic evocation of an appropriate (natural) context for a given

utterance.

184

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 184

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

text overflows with perceptual indicatorswhat the Swede sees, watches, hears,

imagines, dreamsthat mark the texts anchoring to his figural perspective.

Strictly focalized perspective notwithstanding, we should not forget that the

continued employment of third-person references indicates, no matter how unobtrusively, the continued presence of a narrator (Cohn 112). The change concerns crucially the writers relationship with his materials. Zuckerman continues to be present as narrator, as the origin of everything the reader is offered.

Zuckerman conveys the Swedes consciousness resorting to the three types of rendering Dorrit Cohn listspsycho-narration, [thought-report] quoted monologue,

narrated discourse [FID]8 (14).

Let us see (and especially hear). Once Zuckerman is past the foundational

premise that it doesnt matter if he was the cause of anything (88), he seems to

align himself with his protagonists interpretationsthe dream, that is, takes the

form of a (fictive) chronicle.

The first scene Zuckerman (while still dancing with Joy) comes up withbearing all the required features he has already decided upon (failure, responsibility

and transgression)stages a thirty-six-year-old Swede at the seaside with elevenyear-old Merry. To redress what he has just donehe has, inexplicably, made fun

of her stutteringhe kisses her stammering mouth with the passion that she had

been asking him for all month long while knowing only obscurely what she was

asking for (91). How Zuckerman wants this scene to be read and interpreted is

immediately made clear: never in his entire life, not as a son, a husband, a father,

even as an employer, had he given way to anything so alien to the emotional rules

by which he was governed, and later he wondered if this strange parental misstep

was not the lapse from responsibility for which he paid for the rest of his life

(92; my italicsexample of thought-report: the recognizably narratorial discourse

about a characters consciousness). The scene we have witnessed as taking shape

in Zuckermans mind is rewritten away from its real source and as coming from

the Swede as the shift from thought-report to FID suggests: after the disaster,

when he went obsessively searching for the origins of their suffering, it was that

anomalous moment [] that he remembered. [] What went wrong with Merry?

What did he do to her that was so wrong? The kiss? That kiss? So beastly? How

could a kiss make someone into a criminal? (92; my italics)

8I will hereafter (reluctantly) use the term free indirect discourse (FID) instead of Cohns termnarrated monologuebecause the former has become the standard one. My reluctance depends on the awareness that Cohns term

has the unquestionable advantage of maintaining the reference to the inclusion of the narrators voice in its language.

I will use thought-report for the same reason.

185

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 185

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

In the first (figurally focalized) pages, Zuckerman takes great pains in schooling the reader to settle the precise attribution of the emotional tones the text delivers, repeatedly directing him/her toward the Swedes obsessive search: once the

inexplicable had begun, the torment of self-examination never ended (92). The

never-ending quality of the Swedes obsession sustains the fiction of the Swedes

delving unrelentingly into all the significant moments of his daughters lifethe

Audrey Hepburn phase, the catholic phase, speech therapy sessions, her stuttering diary, her Saturday trips to New Yorkdetail after detail after detail. In spite

of this (generous) provision of a naturalizing context, however, the interplay between Zuckermans narratorial statements and the Swedes perceptions and conceptualizations is far from straightforward.

Generally speaking, Zuckerman does not display any special cognitive privilege9 and his diction and style do not transcend the reflectors perceptional or

conceptual ability. And yet, Zuckerman is far from being a covert and unobtrusive narrator: he does not use his voice only to do the typical job a vocal authorial narrator does, that is, to provide contextual informationquotational signals,

chronological underpinnings etc.but, significantly, his overt intrusions take the

atypical10 shape of consonant reinforcements of the Swedes own take on things.

Zuckermans authorial glosses do not maximize the distance between his perception and knowledge and the Swedes but aim at implicating the reader in the

Swedes logic and in his existential predicament.

No wonder he felt so untamed, craving to spill over with talk. Momentarily it was

then againnothing blown up, nothing ruined. As a family they still flew the

flight of the immigrant rocket, the upward, unbroken immigrant trajectory

from slave-driven great-grandfather to self-driven grandfather to self-confident, accomplished, independent father []. No wonder he couldnt shut up.

It was impossible to shut up. The Swede was giving in to the ordinary human

wish to live once again in the past []. (122; my italics)

This paragraph follows the Swedes inebriated talk with a Rita Cohen still in disguise. It displays the artful mixture of FID (in italics) and narratorial commentary (normal text) so typical of American Pastoral. On the one hand, Zuckermans

voice is perfectly recognizable because it actually repeats something we have already heard in the first pages of the book11, on the other, neither the Swede nor

9There is only one proleptical window I am aware of: Meanwhile, under the impetus of that force which, by failing to size up the situation, would lead her into humiliation before the night was through, Jessie went waveringly on (332;

my italics).

10According to Cohns influential distinction either a narrator is intrusive and dissonant or unobtrusive and consonant. See also Fludernik New Wine 624-626.

11Repeatedly in the second section of the book Zuckermans opinions are recognizable to the word.

186

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 186

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

Zuckerman wonder at what has just happened: this means that the same textual

portion may convey both the Swedes and Zuckermans meaning and the italicized

text may actually be an instance of thought-report (rather than FID). The interplay

itself renders overt the change in perspective and implicitly highlights the narrators presence: voiceof any kindcan only be perceived as voice-differentfrom (Aczel, Hearing 478).

The difficulty in settling attributive matters the text may at times present stems

from an overall absence of authorialdissonantrhetoric. After the Swedes possible fallacy has been dismissedhe makes himself responsible anyway (88; my

italics)Zuckerman yields to the Swedes perspective and seems never reluctant

to countenance the appropriateness of his heros reactions (self-delusion included). The narrative situationthe Swedes unique bafflement as representative

of the vaster human bafflement at the mysterious dealings of historypushes

thought-report toward the figural idiom, that is towards what Cohn calls stylistic contagion12 (33). The mimetic quality of the narrative is maintained and reinforced by Zuckermans glosses because the readers attention is not drawn away

from the Swedes interiority. As a result, the reader cannot always tell which is

which as in the above-quoted excerpt. This contagion salvages the illusion of immediacy typical of purely figural narratives and is responsible for Zuckermans

apparent disappearance: it minimizes Zuckermans perceptibility while amplifying the Swedes.13

To decide whether a given statement is a FID or a narratorial comment Toolan

suggests rewriting the dubious sentence in two ways, one explicitly bound to the

narrators and the other to the characters perspective: one of the two (artificial)

sentences typically produces a better fit in terms of content and context (132).

Jahn furthermore extends Toolans suggestions to include a test of internal focalization addressing the issue of who is more likely to conceptualize a given piece

of information in a certain way (Narratology N1.24). It is interesting to note that

the result of these rewritings both confirms the astounding overlapping of the

two perspectivesthe narrators language lapsing into the colour of the characters language, and indicates that, well beyond this double attributive validity

(making the most of FID as a mode of empathetic identification with characters

[McHale, Survey 275]), there are moments in which Zuckermans voice is very

clearly audible.

12The phrase [] designate[s] places where psycho-narration verges on the narrated monologue [:] a reporting

syntax is maintained, but [] the idiom is strongly affected (or infected) with the mental idiom of the mind it renders (Cohn 33).

13This narrative situation looks like the combination of intrusive narratorial voice and strictly focalized perspective

Aczel (Hearing) demonstrates to be peculiarly Jamesian. The obvious and crucial difference concerns the fact that

Zuckerman is very literally an authorial narrator.

187

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 187

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

The most glaring case concerns the (implicit) reference to the book being written: and the following week, with their doctor already arranging for Dawns hospitalization, the Swede went alone to visit Conlons widow. How he managed to

get to that womans house for tea is another storyanother bookbut he did it,

and heroically she served him tea [] (215). Zuckerman cannot go unnoticed in

this sentencethe writer writing this book directing the Swedes movements on

his stage.

Other cases easy to settle concern what Zuckerman literally supplements, namely, what does not occur to the Swede, what he does not imagine: It did not occur

to the Swede that he was right (323); Certainly, seeing Orcutt dressed like that

down in the village [] you would not have imaginedif you were the Swede

his paintings having that rubbed-out look as their distinctive feature (334). This

is a rather typical function of thought-report, the most overtly narratorial mode

of rendering a characters consciousness: there is no way we can will Zuckerman

away from what he knows about his portrait of the Swede.

These obvious (and marginal) cases excluded, I would argue that the key to understanding the peculiar overlapping that American Pastoral is literally built upon

can be grasped in the two quotations that follow:

A beautiful wife. A beautiful house. Runs his business like a charm. Handles

his handful of an old man well enough. He was really living it out, his version of paradise. This is how successful people live. Theyre good citizens.

They feel lucky. (86)

Got to marry a beautiful girl named Dwyer. Got to run a business my father

built, a man whose own father couldnt speak English. Got to live in the prettiest spot in the world. Hate America? Why, he lived in America the way he

lived inside his own skin. (213)

The two excerpts seem to be written on a par: the coordinates of the Swedes

existential set-upwife, house, business, fatherare listed in both; the Swedes

relationship with a vaster geopolitical arena (being a good citizen, America) is

similarly present in both. And yet, they belong in the first and the second

section respectively. In the former, Zuckerman presents a catalogue listing the basic elements of the Swedes world; the present tense conveys a sense of (almost)

Proppian ingredients: Zuckerman rehearses them and while doing it inserts a

sentence in the past tensehe was living it out, his version of paradisewhich

could be read as an instance of thought-report if we were already in the context

of a figural narrative. The plunge into the thought-report mode and the absence

of Zuckermans first person pronoun (before he formally sheds it) make this paragraph a good candidate for the second section here represented by the other

188

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 188

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

quoted excerpt showing a typical mixture of quoted monologue (note the possessive adjective my) and thought-report (or is it FID?). The juxtaposition of these

two paragraphs is not a textual exception, but a rule: Zuckerman formally gives

up the first person pronoun well after he has told and retold about the Swedes

talent for being himself in the third person in the first 90 pages. Indeed, the

readers attention is directed to the Swede starting with the very first words of the

novel spelling out his nickname. The distinctive quality of the perspectival effects

American Pastoral presents lies in the peculiar linguistic mirroring each section

reflects back on the other: Zuckermans absorption in the Swede is uniformly (if

differently) present in both for the rather simple reason that both are the result of

the writers immersion in his childhood years hero: we should not forget that the

high-school reunion dance is the seminal source of the whole bookchildhood

memories included. Sentences echo each other playing the subtle game of burying a difference within a sameness as in the different indexing of the personal

pronoun we (the first excluding Zuckerman, the second including himthe

strongest possible marker, if need be, of Zuckermans presence in this second

section) in the following excerpts:

Thinking: She is not in my power and she never was. She is in the power of

something that does not give a shit. Something demented. We all are.

Yes, at the age of thirty-six, in 1973, [] the Swede found out that we are all

in the power of something demented. (256)

This minimal change foregrounds unmistakably the narrators voice.

The famous close of the book presents a narratological abridgement of this

multi-layer mirroring.

Yes, the breach had been pounded in their fortification, even out here in secure

Old Rimrock, and now that it was opened it would not be closed again. []

And whats wrong with their life? What on earth is less reprehensible than

the life of the Levovs? (423; my italics)

Whose voice is this? It would seem easy to file this sentence with Zuckerman

as it echoes the very metaphor the writer had already used at the very beginning

of the bookThe daughter and the decade blasting to smithereens his particular

form of utopian thinking, the plague America infiltrating the Swedes castle and

there infecting everyone (8; my italics). And yet chapter eight closes with a very

similar image to be ascribed to the Swede: Dawn and Orcutt: two predators.

The outlaws are everywhere. They are inside the gates (366). Thus if the closing words can certainly be attributed to Zuckerman who closes the curtain on the

Swedes performance with a rhetorical question concerning the very subject of the

189

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 189

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

whole bookthe mysterious (and baffling) discrepancy between a good seed and

its foul fruitthey seem to emerge from a chorus-like, polyphonic substratum.

The resulting dialogic contamination is signaled and condensed in the presence

of two deicticshere and nowwhich plant into a clearly narratorial gloss a jarring element mining it from within. The (desired) consequence is that the commentary becomes a sort of hybrid, an in-between form posing the narrator in the

here and now of his beloved protagonistthe formal manifestation of inhabiting

the Swede Zuckerman had spoken about in the meta-narrative aside in the middle of chapter three.

Zuckermans empathetic (often hybridized) presence alongside the suffering

Swede is what the reader witnesses throughout the whole second section of the

book. First throughout the five years after Merrys bombing and her disappearance while he is besieged by a gruesome inner life of tyrannical obsessions (173)

and then during the final attack on his psyche taking place on Sept 1, 1973. It is no

wonder that the quantitative relationship between FID and narrative context mirrors the progressive narrowing in on the Swedes short-circuiting ruminations ignited by Rita Cohens letter: FID intensifies while the Swede is being unmade by

steadily sinking under the weight (384) of new disruptive revelations. FID is essentially an evanescent form, dependent on the narrative voice that mediates and

surrounds it, and is therefore peculiarly dependent on tone and context (Cohn

116). In other words, it is in the very nature of this device to throw into relief the

narrators presence at the very moment it seems to obscure it. Significantly enough,

the terms of sincere endearment the writer displays intensify in this part of the book

with the contextual intensification of FID (the best mode to confer naturalness to

stream-of-consciousness) and long stretches of (often unsignaled) quoted monologues in the first-person or thought-report stripped to its almost Faulknerian extreme (Thinking: Futile, every last think he had ever done [...] 256).

The dilatation of the time of narration to reflect the narrated time makes this

day a memorable literary tour de force: each single event the Swede has to face

during the long excruciating day triggers a long flashback through which the

protagonist tries to come up for the last time with an answer to explain what

was beyond understanding (238). Each single new revelation the Swede has to

face, each plunge he takes into the past is glossed by Zuckerman with empathy.

About his acceding to Dawns decision to build a new house (and the consequent

flashback on his dream of living in the old stone house), we hear Zuckerman say:

that was the only way the Swede knew for a man to go about being a man

(201). During the phone call with Jerry which brings the Swede to tears, we hear

Zuckerman stop the flow of the conversation to think out loud: and these two

brothers, the same parents sons, one for whom the aggressions been bred out,

190

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 190

23/09/11 12:12

N a r r at i n g t h e Pa s t o r a l

the other for whom the aggressions been bred in (278). We hear Zuckerman

back up the Swede concerning the place to settle in with Dawn: But the Swede,

rather like some frontiersman of old, would not be turned back. What was impractical and ill-advised to his father was an act of bravery to him (310). After

the recollection of the Swedes visits to a hospitalized Dawn, we hear Zuckerman

provide the link for the following flashback concerning his wife: it was a great

help to him, driving home after one of those visits, to remember her as the girl she

really was (181). We hear Zuckerman opening a window on his protagonists remembering the Thanksgiving dinners the Levovs and the Dwyers spent together:

so the deal was cut, the youngsters were married [] and both families got together every year for Thanksgiving dinner up in Old Rimrock (400); and closing

it it is the American pastoral par excellence and it lasts twenty-four hours (402).

Examples abound.

I started this narratological journey by spelling out the questions my students

ask me when I teach American Pastoral: Where is Zuckerman? Why does he not return to wrap up the Swedes story? There is only one answer: Zuckerman is everywhere, audible in ways I hope I have made sufficiently clear. Nothing is impersonally perceived (167) and as such everything is personally accounted for in the

fluid space between dream and chronicleanother, masterful chapter in Philip

Roths ongoing exploration of the relationship between a writer and his materials.

Works Cited

Aczel, Richard. Commentary: Throwing Voices. New Literary History 32.3

(2001): 703-705.

. Hearing Voices in Narrative Texts. New Literary History 29 (1998):

467-500.

Cohn, Dorrit. Transparent Minds. Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in

Fiction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Fludernik Monika. Towards a Natural Narratology. London: Routledge, 1996.

. New Wine in Old Bottles? Voice, Focalization, and New Writing. New

Literary History 32.3 (2001): 619-638.

Jahn, Manfred. Windows of Focalization: Deconstructing and Reconstructing a

Narratological Concept. Style 30.2 (Summer 1996): 241-267.

. Narratology. A Guide to the Theory of Narrative. 28 May 2005. 23 July 2011.

<http://www.uni-koeln.de/~ame02/pppn.htm>.

191

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 191

23/09/11 12:12

R e a d i n g P h i l i p R o t h s A m e r i c a n Pa s t o r a l

Masiero, Pia. Philip Roth and the Zuckerman Books. The Making of a Storyworld.

Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2011.

McHale, Brian. Free Indirect Discourse: A Survey of Recent Accounts. PTL: A

Journal for Descriptive Poetics and Theory of Literature 3 (1978): 249-287.

Toolan, Michael. Narrative. A Critical Linguistic Introduction. 2nd ed. London:

Routledge, 2001.

. The irresponsibility of FID. Ed. P. Tammi and H. Mommola. FREE language INDIRECT translation DISCOURSE narratology. Tampere: Tampere

University Press, 2006: 261278.

192

Amphi7_ReadingPhilipRothAP.indd 192

23/09/11 12:12

Você também pode gostar

- Glossery of Terms Related To NarrativeDocumento5 páginasGlossery of Terms Related To NarrativeTaibur RahamanAinda não há avaliações

- Doing More with One Life: A Writer's Journey through the Past, Present, and FutureNo EverandDoing More with One Life: A Writer's Journey through the Past, Present, and FutureAinda não há avaliações

- Julius - Maximilians - Universität WürzburgDocumento17 páginasJulius - Maximilians - Universität WürzburgShreeparna DeyAinda não há avaliações

- Literary Sudies TestDocumento6 páginasLiterary Sudies TestMaría AlejandraAinda não há avaliações

- W or The Memory of Childhood.: Link/Page CitationDocumento7 páginasW or The Memory of Childhood.: Link/Page CitationŁukasz ŚwierczAinda não há avaliações

- In The Belly Of The Dragon: A Zen Monk's Commentary on the SHINJINMEI by Master Sosan (D. 606)No EverandIn The Belly Of The Dragon: A Zen Monk's Commentary on the SHINJINMEI by Master Sosan (D. 606)Ainda não há avaliações

- The Breakwater Book of Contemporary Newfoundland Short FictionNo EverandThe Breakwater Book of Contemporary Newfoundland Short FictionNota: 2.5 de 5 estrelas2.5/5 (3)

- Types of Weltschmerz in German Poetry by Braun, Wilhelm Alfred, 1873Documento68 páginasTypes of Weltschmerz in German Poetry by Braun, Wilhelm Alfred, 1873Gutenberg.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Critical ApproachesDocumento7 páginasCritical ApproachesJustin BaptistaAinda não há avaliações

- Plot and ThemeDocumento6 páginasPlot and ThemeSumi SenseiAinda não há avaliações

- Faith Rising—Between the Lines: Intimations of Faith Embedded in Modern FictionNo EverandFaith Rising—Between the Lines: Intimations of Faith Embedded in Modern FictionAinda não há avaliações

- Anastasia Englis (PDFDrive)Documento209 páginasAnastasia Englis (PDFDrive)Gomesz TataAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis - of - Main - Characters - and - Major - TH (AutoRecovered)Documento16 páginasAnalysis - of - Main - Characters - and - Major - TH (AutoRecovered)Minh NgọcAinda não há avaliações

- The Face in The PoolDocumento10 páginasThe Face in The Poolshark777Ainda não há avaliações

- The Christmas Victory, A Gem of a Sermon, All Wrapped Up In a Historical NovelNo EverandThe Christmas Victory, A Gem of a Sermon, All Wrapped Up In a Historical NovelAinda não há avaliações

- Franny and Zooey and Me The Mystical WriDocumento15 páginasFranny and Zooey and Me The Mystical Wriffggttaqxw8Ainda não há avaliações

- The Poet at the Breakfast Table: “A moment's insight is sometimes worth a life's experience.”No EverandThe Poet at the Breakfast Table: “A moment's insight is sometimes worth a life's experience.”Ainda não há avaliações

- The Butler'S Suspicious Dignity: Unreliable Narration in Kazuo Ishiguro'SDocumento12 páginasThe Butler'S Suspicious Dignity: Unreliable Narration in Kazuo Ishiguro'SLiudmyla HarmashAinda não há avaliações

- JG Ballard and The Death of Affect, Part 2Documento9 páginasJG Ballard and The Death of Affect, Part 2Jon MoodieAinda não há avaliações

- A Scholar's Tale: Intellectual Journey of a Displaced Child of EuropeNo EverandA Scholar's Tale: Intellectual Journey of a Displaced Child of EuropeNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (3)

- 10 2 Madden PDFDocumento8 páginas10 2 Madden PDFnoammAinda não há avaliações

- The Subjective Search For The Meaning of Life in To The LighthouseDocumento2 páginasThe Subjective Search For The Meaning of Life in To The LighthouseJuan Cruz Perez100% (2)

- Summer Internship Project Report ANALYSIDocumento60 páginasSummer Internship Project Report ANALYSIKshitija KudacheAinda não há avaliações

- Manual ML 1675 PDFDocumento70 páginasManual ML 1675 PDFSergio de BedoutAinda não há avaliações

- LANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsDocumento2 páginasLANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsAnneAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology: DR - Wasfi Dhahir Abid AliDocumento9 páginasPathophysiology: DR - Wasfi Dhahir Abid AliSheryl Ann PedinesAinda não há avaliações

- Prelims CB em Ii5Documento21 páginasPrelims CB em Ii5Ugaas SareeyeAinda não há avaliações

- Ahu 1997 22 1 95Documento15 páginasAhu 1997 22 1 95Pasajera En TranceAinda não há avaliações

- Vehicles 6-Speed PowerShift Transmission DPS6 DescriptionDocumento3 páginasVehicles 6-Speed PowerShift Transmission DPS6 DescriptionCarlos SerapioAinda não há avaliações

- American University of Beirut PSPA 210: Intro. To Political ThoughtDocumento4 páginasAmerican University of Beirut PSPA 210: Intro. To Political Thoughtcharles murrAinda não há avaliações

- Microcontrollers DSPs S10Documento16 páginasMicrocontrollers DSPs S10Suom YnonaAinda não há avaliações

- OSX ExpoDocumento13 páginasOSX ExpoxolilevAinda não há avaliações

- Weather Prediction Using Machine Learning TechniquessDocumento53 páginasWeather Prediction Using Machine Learning Techniquessbakiz89Ainda não há avaliações

- Hypoglycemia After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Current Concepts and Controversies 2018Documento12 páginasHypoglycemia After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Current Concepts and Controversies 2018Rio RomaAinda não há avaliações

- Test Bank For Global Marketing Management 6th Edition Masaaki Mike Kotabe Kristiaan HelsenDocumento34 páginasTest Bank For Global Marketing Management 6th Edition Masaaki Mike Kotabe Kristiaan Helsenfraught.oppugnerp922o100% (43)

- 3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Documento66 páginas3.1.1 - Nirmaan Annual Report 2018 19Nikhil GampaAinda não há avaliações

- 184 Учебная программа Английский язык 10-11 кл ОГНDocumento44 páginas184 Учебная программа Английский язык 10-11 кл ОГНзульфираAinda não há avaliações

- Math 10 Week 3-4Documento2 páginasMath 10 Week 3-4Rustom Torio QuilloyAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Care Plan For AIDS HIVDocumento3 páginasNursing Care Plan For AIDS HIVFARAH MAE MEDINA100% (2)

- Case StarbucksDocumento3 páginasCase StarbucksAbilu Bin AkbarAinda não há avaliações

- Bridging The Divide Between Saas and Enterprise Datacenters: An Oracle White Paper Feb 2010Documento18 páginasBridging The Divide Between Saas and Enterprise Datacenters: An Oracle White Paper Feb 2010Danno NAinda não há avaliações

- IJREAMV06I0969019Documento5 páginasIJREAMV06I0969019UNITED CADDAinda não há avaliações

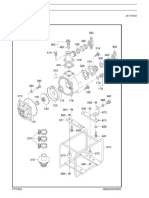

- Workshop Manual: 3LD 450 3LD 510 3LD 450/S 3LD 510/S 4LD 640 4LD 705 4LD 820Documento33 páginasWorkshop Manual: 3LD 450 3LD 510 3LD 450/S 3LD 510/S 4LD 640 4LD 705 4LD 820Ilie Viorel75% (4)

- On The Margins - A Study of The Experiences of Transgender College StudentsDocumento14 páginasOn The Margins - A Study of The Experiences of Transgender College StudentsRory J. BlankAinda não há avaliações

- Guide For Sustainable Design of NEOM CityDocumento76 páginasGuide For Sustainable Design of NEOM Cityxiaowei tuAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction Paper GattacaDocumento1 páginaReaction Paper GattacaJoasan PutongAinda não há avaliações

- Opentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideDocumento38 páginasOpentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideDoond adminAinda não há avaliações

- New Horizon Public School, Airoli: Grade X: English: Poem: The Ball Poem (FF)Documento42 páginasNew Horizon Public School, Airoli: Grade X: English: Poem: The Ball Poem (FF)stan.isgod99Ainda não há avaliações

- Design of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyDocumento6 páginasDesign of Ka-Band Low Noise Amplifier Using CMOS TechnologyEditor IJRITCCAinda não há avaliações

- PTD30600301 4202 PDFDocumento3 páginasPTD30600301 4202 PDFwoulkanAinda não há avaliações

- Centric WhitepaperDocumento25 páginasCentric WhitepaperFadhil ArsadAinda não há avaliações