Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

6 Steps For Creating Problems Statements

Enviado por

NurMunirahBustamamTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

6 Steps For Creating Problems Statements

Enviado por

NurMunirahBustamamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

Volume 2, Number 11

Strategies To Win:

Six-Steps For Creating Problem Statements

In Doctoral Research

Kimberly D. Blum, (Email: kdblum@email.uophx.edu), University of Phoenix Online

Amy E. Preiss, (Email: amypreiss@sbcglobal.net), University of Phoenix Online

ABSTRACT

The problem in a doctoral dissertation is the most critical component of the study. (Creswell, 2004;

Simon & Francis, 2004; Sproull, 1995). The problem explains the rationale for the study, validates

its importance, and determines the research design. Many students do not know how to write a

problem statement despite its importance (Simon & Francis, 2004). Currently no systematic process

exists to teach students how to write a problem statement. The problem is compounded for distance

education students who do not have face-to-face instructor contact. This article will present a sixstep method for teaching online doctoral students how to write a problem statement. The process is

used at the University of Phoenix Online School of Advanced Studies (SAS).

INTRODUCTION

he problem in a doctoral dissertation is the most critical component of the research proposal (Creswell,

2004; Simon & Francis, 2004; Sproull, 1995). The problem explains the rationale for the study,

validates its importance, and determines the research design. Many students do not know how to write

a problem statement despite its significance to the overall success of a study (Simon & Francis, 2004). Currently no

systematic process exists to teach students how to write a sound problem statement. The problem is compounded for

distance education students who do not have the benefit of face-to-face instructor contact. This article will present a

six-step method for teaching online doctoral students how to write a problem statement. The process is used at the

University of Phoenix Online School of Advanced Studies (SAS).

The University of Phoenix School of Advanced Studies (SAS) enrolls 4,000 online doctoral students (School

of Advanced Studies, 2005). According to Lee (2001), the online student population in higher education is expected to

increase by 33 percent by the year 2004. Of these students, high percentages are expected to enroll in doctoral

education increasing the need for teaching students how to write problem statements

CREATING A PROBLEM STATEMENT

Writing a problem statement can be compared to a professional racecar driver strategically reducing speed

before going around a steep turn. Slowing down increases the drivers ability to control the car and defeat drivers who

accelerated too quickly and lost control of the car. Slowing down initially enables the driver to win the race. Students

writing a problem statement should implement a similar strategy. Students should take time to consider what

constitutes a viable problem before writing the problem statement. Doctoral learners should slow down, consider the

problem to explore and devise a strategic plan. If students invest this time initially, they will experience less difficulty

in completing the remaining parts of the proposal. Online faculty and dissertation mentors play a critical role in

guiding students in the research and writing process. Since the problem statement lays the foundation for impending

research, faculty should not overlook its importance. One of the authors of this article created a six-step process for

creating problem statements. The process evolved from years of experience mentoring distance education doctoral

researchers and observing learner difficulty in writing problem statements. The process for creating successful

47

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

Volume 2, Number 11

problem statements includes the following six components: (a) identify and select a problem, (b) define the problem,

(c) determine the research design, (d) state the relevance, (e) cite research, and (f) share the checklist.

Creating The Problem Statement Step One -- Identify And Select A Problem

The first step in writing a good problem statement is to help students reflect on the problem they want to

study. The problem must be significant enough to warrant dissertation research. According to UOP administration, a

problem statement is concise (100-250 words) and has enough information to convince readers the research is

feasible, appropriate and worthwhile for leaders (R. Schuttler, personal communication, April 24, 2003). The

researcher must convey to the reader that there is a real problem needing clarity or understanding.

Students should select a problem aligned with their passion. Students should care deeply about the problem

and be driven to find an answer. Students should also have experience with the topic, have access to data, and be able

to work in the timeframe allotted.

Some students enter the doctoral program driven by a need to know. The problem is the reason they enrolled

in the program. Though the problem may change slightly, the student remains driven by the academic passion. These

students are typically exceptions to the norm.

Most students realize their passion after enrolling in several classes and becoming exposed to new

information and ideas. Some students have difficulty selecting a problem. Online faculty can help students select a

problem, and use a variety of coaching techniques. One technique is to advise students to select a problem related to

their job, environment, or home life. Faculty instructs student to develop a list of five likes and five dislikes, read the

list aloud to others, and ask them to listen for voice tone changes. Voice changes may indicate an interest area.

Another technique is to have students research potential topics or interests focusing on implications for future research

that may be of interest. The student reports findings to the faculty member who helps narrow the problem to a specific

population.

Creating The Problem Statement Step Two -- Define The Problem

Once students have selected a problem, the next step is to write the first sentence of the problem statement.

Online SAS faculty should urge eager students to slow down and write one sentence at a time. Student should not

move to the next sentence without revising the bottom-line problem repeatedly until it is clear to the reader. To start

this process, faculty instructs online SAS students to complete their answers to the statement: The problem

is...whatfor who...where.

Examples Of Bottom-Line Problems

The problem is at risk secondary students at Coatesville Area School District located in a middle class

suburb of Northeastern Pennsylvania are not meeting the NCLB (2001) mandates in reading.

The problem is any transformational effects of outreach education programs offered by the Community,

Natural Resource, and Economic Development Program Area (CNRED) of the University of WisconsinExtension is unmeasured throughout Wisconsin communities.

The problem is eighth grade African American students in Highland Park Schools, Michigan do not

achieve the same academic levels as non-minority students from Birmingham School District, Michigan.

The problem is there is little knowledge of what executive leadership traits result in higher organizational

yearly profits for mid-sized high-tech firms in Silicon Valley, California.

The problem is the glass ceiling has kept qualified and experienced women from achieving promotions in

New England in higher education

The problem is little research has been conducted on online best practices for facilitators at the k12 levels

of education.

48

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

Volume 2, Number 11

If the problem definition is sound, a student should be able to explain it to a stranger in an elevator between

the second and third floors. If a student can state the problem in one sentence, and the stranger understands the

problem, the student has a good first line of a formal problem statement. At the University of Phoenix, online doctoral

students enroll in a class specifically geared toward dissertation writing. The class newsgroup serves as a drafting

board for students to post problem statements and obtain feedback on each line. Each student can see classmates

statements and can learn from faculty suggestions. Since no grades are awarded until the fifth week of class, (online

classes are eight weeks long) students can participate freely without fearing penalty for mistakes.

Creating the Problem Statement Step Three Select Research Design

After the problem has been clearly stated, (this typically takes a few student revisions with faculty feedback)

faculty instructs students to add the second line of the problem. The second line of a problem statement states what

needs to be accomplished to solve the problem and should state the research design (Creswell, 2004; Simon &

Francis, 2004). Selecting the right research design is critical. If the research design does not match the problem it will

be difficult, if not impossible, to conduct the research study. Students should understand research design methodology

before conducting the actual study.

SAS faculty teach students about quantitative and qualitative research designs by posting lectures in the

classroom newsgroup. Students must understand the difference between the two methods to choose the appropriate

design. Qualitative designs explore data for possible unknown themes to determine what, how, and why, while

quantitative designs focus on establishing a correlation or relationship among variables. Faculty should coach students

to carefully consider research designs before writing the second line of the problem statement.

The second line of the problem statement should immediately follow the first. The first line described the

problem. The second line should specify the approach the student will take to explore the problem. To develop the

second line of the problem statement students should complete answers to the statement: this type of design

(qualitative, quantitative) study will do what (explore, describe) what (topic) by doing what (interviewing, observing)

who (subjects or population) where (location). If the study is qualitative, students should explain how research

patterns would be triangulated. By combining results from at least three different sources, it is possible to triangulate

information and increase confidence in its reliability.

Second problem statement line examples (first line of statement included).

The problem is that 80% of foster children in the United States placed by foster care leaders into long-term

foster care homes have been identified as having clinically significant behavior problems (Farmer, Burns, Chapman,

Phillips, Angold & Costello, 2001). This qualitative case study will examine 40 historical files of children at a

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, foster care agency to examine themes of leadership placement practices that might

contribute to reduced reported problems of children placed in long-term foster care as measured by reports of less than

three times a week of foster care problems.

The problem is that parent-teacher group leaders are inadequately trained in leadership and do not effectively

share leadership roles with principals (Haar, 2002). This quantitative research descriptive study will survey

elementary PTO leaders and principals in New Hampshire public elementary schools to gather information on

perceived leadership skills as they relate to school success defined by parent involvement rates and standardized third

grade reading test scores.

Creating the Problem Statement Step Four Determining Relevance

Once the bottom-line problem has been revised and the research design added, faculty should have students

write the last line of the problem statement. The last line of the problem statement should be a concise one-line

statement telling readers who might care about the results of the study.

49

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

Volume 2, Number 11

Creating the problem statement step four example

The problem is little research has been conducted on best practices for online facilitators in grades k12

(Rudestam & Schoenholtz-Read, 2002). This qualitative study will survey and interview teachers in an asynchronous

online learning environment in Southern California to determine best practices for teaching future k12 online classes.

This research will seek to determine online teaching practices to improve the k-12 online classroom, support the

transition to online learning in grades k12, promote successful teaching strategies in the online k12 classroom, and

prepare the traditional on ground teacher for the role of facilitator in online education. (Baker, 2004).

Problem Statement Creation Step Five Cite Research

This step of the problem statement involves citing relevant research. Citing research accentuates the

importance of the problem and validates the need for study. This step is typically the most difficult. Students

conducting dissertation research read countless studies. It is often difficult to select the one or two studies most

strongly supporting the problem. Faculty should therefore advise students to complete step five after steps one through

four are complete. As a rule, supporting research should be brief (two or three statements) and should precede the first

line of the problem statement.

Creating the problem statement step five adding theories and final problem statement example.

The NCLB Act of 2002 stipulates that by the end of eighth grade, every student will be technologically

literate. Much research has been dedicated to best practices for online learning at the postsecondary level (Billing &

Connors, n.d.; Palloff & Pratt, 2001) employing adult learning techniques (Caffarella, 2002; Garrison & Anderson,

2003). The problem is little research has been conducted on best practices for online facilitators in grades k12.

(Rudestam & Schoenholtz-Read, 2002). This qualitative study will survey and interview teachers in an asynchronous

online learning environment in Southern California to determine best practices for teaching future k12 online classes.

This research will seek to determine online teaching practices to improve the k-12 online classroom, support the

transition to online learning in grades k12, promote successful teaching strategies in the online k12 classroom, and

prepare the traditional on ground teacher for the role of facilitator in online education (Baker, 2004).

Creating the Problem Statement Step Six: Share the Problem Statements Checklist

Once the final problem statement is complete, SAS faculty members provide the following checklist.

Students evaluate their statement against the checklist before submitting their problem statement for a final grade.

Go backwards. Ensure a stranger could understand your problem in no more than 250 words.

Answers the question: What is wrong in society?

Answers the question: What program needs evaluation?

Answers the question: What accepted practice needs to be revisited?

Determines where the problem exists or is under study (specific organizations or areas of the country).

Determines what group is impacted by problem (teachers, students, etc)

Describes what needs to be done (evaluate, explore, test, understand, describe).

Describes the type of design and how data will be collected.

Describes the geographical location of the population.

Determines how others can benefit from findings.

CREATING THE PROBLEM STATEMENT CREATION: A SYSTEMATIC SUMMARY

The following summarizes the six-step process for completing problem statements. To begin writing a

problem statement, researchers should complete the sentence: the problem is...whatfor who...where. This is the first

line. Next, researchers should include the design matched to solve the problem by completing the statement: this (type

of design) study will do what (explore, describe) what (topic) by doing what (interviewing, observing) who (subjects,

population) where (location). The design is the second line.

50

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

Volume 2, Number 11

If the study is qualitative, students should include how research patterns will be triangulated. Finally,

students should determine who might be impacted by the research results. The last line of the problem statement

should be a concise, one-line statement telling the reader who might care about the final results. After all steps are

complete, students should cite theories validating the importance of their study. Students should cite two to three lines

of text before the first line of the overall problem statement. The entire problem statement should be approximately

250 words, and students should check the final version against the problem statement checklist.

CONCLUSION

The problem statement is the most critical element of the doctoral dissertation. The problem statement

explains the rationale for the study, validates its importance, determines the research design, and ensures reliability.

The importance of teaching beginning researchers how to write a problem statement cannot be overestimated. Faculty

must realize the process takes time, and they must exercise dedication and patience. Faculty can minimize students

fear and build their confidence by using a six-step process. As faculty guide students through each step, they are

helping them create a final statement designed to win to drive the racecar to the finish line!

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Billing, D. M., & Connors H. R. (n.d.). National Learning Network living book: Best practices in online

learning. Retrieved February 28, 2004, from http://www.electronicvision.com/nln/chapter02/

Caffarella, R. S. (2002). Planning programs for adult learners: A practical guide for educators, trainers, and

staff developers (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J. W. (2004). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and

qualitative research (2nd ed.). Columbus, Ohio: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Farmer, E. M., Burns, B. J., Chapman, M. V., Phillips, S. D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2001). Use of

mental health services by youth in contact with social services. Social Service Review, 75, 605624.

Garrison, D. R. & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and

practice. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Haar, C. (2002). Politics of the PTA. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Lee, G.S. (2001). The rhetoric and reality of e-learning. New Straits Times, 27 August, pp. 18ff.

Palloff, R. M. & Pratt, K (2001). Lessons from the cyberspace classroom: The realities of online teaching.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rudestam, E. & Schoenholtz-Read, J. (2002). Handbook of online learning: Innovations in higher education

and corporate training. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Simon, M. K. & Francis, B. J. (2004). The dissertation cookbook: From soup to nuts a practical guide to

start and complete your dissertation (3rd. Ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt.

Sproull, N. D. (1995). Handbook of research methods: A guide for practitioners and students in the social

sciences (2nd. Ed.). New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press.

Sproull, N. D. (2004). Handbook of research methods: A guide for practitioners and students in the social

sciences (3rd Ed.). New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press.

51

Journal of College Teaching & Learning - November 2005

NOTES

52

Volume 2, Number 11

Você também pode gostar

- Assignment 3 - Skills Related Task CELTADocumento7 páginasAssignment 3 - Skills Related Task CELTAAmir Din75% (8)

- Siop Lesson Plan PDFDocumento13 páginasSiop Lesson Plan PDFKarly Sachs100% (2)

- Definition of Remedial CourseworkDocumento5 páginasDefinition of Remedial Courseworkafiwfnofb100% (2)

- Sample Thesis Classroom ManagementDocumento5 páginasSample Thesis Classroom Managementerinperezphoenix100% (1)

- Chapter 4 Thesis PresentationDocumento5 páginasChapter 4 Thesis Presentationtanyawilliamsomaha100% (2)

- Modelos Proteinas 6Documento16 páginasModelos Proteinas 6GabrielCamarenaAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Chapter 1 and 2Documento6 páginasThesis Chapter 1 and 2Christine Williams100% (2)

- Thesis Graduate StudentDocumento4 páginasThesis Graduate Studentmiamaloneatlanta100% (2)

- Thesis Title On Classroom ManagementDocumento6 páginasThesis Title On Classroom Managementchristydavismobile100% (2)

- Research Defense PreparationDocumento7 páginasResearch Defense PreparationChrysje Earl Guinsan TabujaraAinda não há avaliações

- Ten Worst Teaching Mistakes (Continued) : Mistake #4. Give Tests That Are Too LongDocumento4 páginasTen Worst Teaching Mistakes (Continued) : Mistake #4. Give Tests That Are Too LongtonykptonyAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Questionnaire For Thesis About Academic PerformanceDocumento7 páginasSample Questionnaire For Thesis About Academic PerformancerqopqlvcfAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching Performance ThesisDocumento6 páginasTeaching Performance Thesismandyhebertlafayette100% (2)

- Action Research PDFDocumento79 páginasAction Research PDFMaria Fatima CaballesAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Title For Education 2014Documento8 páginasThesis Title For Education 2014BestPaperWritingServiceUK100% (2)

- Module 3 Action Research Problem ConceptualizationDocumento17 páginasModule 3 Action Research Problem ConceptualizationDora ShaneAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Marking FeedbackDocumento5 páginasDissertation Marking FeedbackSomeoneWriteMyPaperSavannah100% (1)

- Thesis Chapter 4 and 5 FormatDocumento8 páginasThesis Chapter 4 and 5 Formatgbwy79ja100% (2)

- Thesis PerformanceDocumento5 páginasThesis Performancegof1mytamev2100% (2)

- Jurnal Metopel 3Documento10 páginasJurnal Metopel 3Ihsan RabaniAinda não há avaliações

- 10 1 1 149 3936Documento18 páginas10 1 1 149 3936Stojan SavicAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation About Educational ManagementDocumento5 páginasDissertation About Educational ManagementHelpWritingAPaperOmaha100% (1)

- Effects of Cutting Classes For Grade 11 TEC Students in AMA Computer College Las Piñas (S.Y. 2018-2019)Documento9 páginasEffects of Cutting Classes For Grade 11 TEC Students in AMA Computer College Las Piñas (S.Y. 2018-2019)GgssAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Background of The ProblemDocumento5 páginasThesis Background of The ProblemWhereCanIFindSomeoneToWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Dissertation About K To 12Documento6 páginasDissertation About K To 12WhereToBuyWritingPaperGilbert100% (1)

- Fun Paper 1 Fall 2011 InstructionsDocumento20 páginasFun Paper 1 Fall 2011 InstructionsSuk SeoAinda não há avaliações

- Final OutputDocumento19 páginasFinal OutputJhaixa MicahAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Chapter One FormatDocumento5 páginasThesis Chapter One Formataflodnyqkefbbm100% (2)

- Thesis School Based ManagementDocumento7 páginasThesis School Based Managementwfwpbjvff100% (2)

- SSRN Id1612050Documento7 páginasSSRN Id1612050Archie AlborAinda não há avaliações

- Effective-Teaching MethodsDocumento167 páginasEffective-Teaching Methodstrjoe2025Ainda não há avaliações

- Academic Honesty and DraftDocumento5 páginasAcademic Honesty and DraftRohin SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Creating A TBL Module Sibley Creative CommonsDocumento8 páginasCreating A TBL Module Sibley Creative CommonsLee -Ainda não há avaliações

- Compre QuestionsDocumento5 páginasCompre QuestionsGerone Tolentino AtienzaAinda não há avaliações

- Learning Transfer DissertationDocumento9 páginasLearning Transfer DissertationHelpWithPapersCanada100% (1)

- 5452 21342 1 PBDocumento6 páginas5452 21342 1 PBZiia Fujiah HigianiAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 Thesis ExampleDocumento5 páginasChapter 4 Thesis Examplelniaxfikd100% (1)

- RESEARCH2Documento22 páginasRESEARCH2Kylrene Jane MomoAinda não há avaliações

- Research in Eapp Final 2.docx DimlerDocumento12 páginasResearch in Eapp Final 2.docx Dimlerdjeanbatilo04Ainda não há avaliações

- Sample Thesis Chapter 1-5Documento4 páginasSample Thesis Chapter 1-5prdezlief100% (2)

- ReflectionDocumento6 páginasReflectionapi-277207317Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1: Cutting Classes ResearchDocumento8 páginasChapter 1: Cutting Classes ResearchTyler Bert76% (42)

- Dentifying A Need For Web Based Course Support: KeywordsDocumento9 páginasDentifying A Need For Web Based Course Support: KeywordsRudyta NingsihAinda não há avaliações

- End of Course WorkDocumento7 páginasEnd of Course Workjgsjzljbf100% (2)

- Student Assessment in Online Learning: Challenges and Effective PracticesDocumento11 páginasStudent Assessment in Online Learning: Challenges and Effective PracticesUmmi SyafAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper About Academic PerformanceDocumento4 páginasResearch Paper About Academic Performanceuziianwgf100% (1)

- Action Research Paper Classroom ManagementDocumento4 páginasAction Research Paper Classroom Managementgzzjhsv9100% (1)

- Assessment ProjectDocumento14 páginasAssessment Projectapi-408772612Ainda não há avaliações

- Education Thesis TitlesDocumento5 páginasEducation Thesis Titlesbrittneysimmonssavannah100% (1)

- Graduated Difficulty LessonDocumento18 páginasGraduated Difficulty Lessonapi-285996086Ainda não há avaliações

- Session 7 Habib KhanDocumento11 páginasSession 7 Habib Khanu0000962Ainda não há avaliações

- Thesis Title For Education in The PhilippinesDocumento4 páginasThesis Title For Education in The Philippineswbrgaygld100% (2)

- Student Engagement Strategies For The ClassroomDocumento8 páginasStudent Engagement Strategies For The Classroommassagekevin100% (1)

- Research Paper On Educational ManagementDocumento7 páginasResearch Paper On Educational Managementhyz0tiwezif3100% (1)

- Literature Review For Student Feedback SystemDocumento8 páginasLiterature Review For Student Feedback Systemea8dpyt0100% (1)

- Evolution of Student Attitudes FinalDocumento14 páginasEvolution of Student Attitudes FinalAmar CinkerAinda não há avaliações

- Problem and Its Setting Thesis SampleDocumento6 páginasProblem and Its Setting Thesis Samplesandragibsonnorman100% (2)

- Scenar Io Based Exer Cises in IA Cour Ses: Walsh College Walsh CollegeDocumento7 páginasScenar Io Based Exer Cises in IA Cour Ses: Walsh College Walsh Collegeamali23Ainda não há avaliações

- Sample Thesis Chapter 4 Presentation Interpretation and Analysis of DataDocumento7 páginasSample Thesis Chapter 4 Presentation Interpretation and Analysis of Datadeniselopezalbuquerque100% (2)

- Difficulties Encountered by The StudentsDocumento30 páginasDifficulties Encountered by The Studentsisaac e ochigboAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 Thesis Presentation and Analysis of DataDocumento7 páginasChapter 4 Thesis Presentation and Analysis of Datavetepuwej1z3100% (2)

- Motivating for STEM Success: A 50-step guide to motivating Middle and High School students for STEM success.No EverandMotivating for STEM Success: A 50-step guide to motivating Middle and High School students for STEM success.Ainda não há avaliações

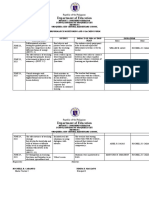

- PMCF 4th QDocumento2 páginasPMCF 4th QRoch Shyle NeAinda não há avaliações

- British Study Centres - CELTA Course BrochureDocumento12 páginasBritish Study Centres - CELTA Course BrochureDan GROSUAinda não há avaliações

- A Borsa Resume WebsiteDocumento2 páginasA Borsa Resume Websiteapi-249524864Ainda não há avaliações

- Directorate of Distance Education Guru Jambheshwar University of Sc. & Tech. HisarDocumento8 páginasDirectorate of Distance Education Guru Jambheshwar University of Sc. & Tech. Hisarw_s_lionardoAinda não há avaliações

- Y1 Phonics Lesson 7Documento2 páginasY1 Phonics Lesson 7Mohamad Nur Al HakimAinda não há avaliações

- Barriers For Students With Dyslexia in Public Education (New York State)Documento7 páginasBarriers For Students With Dyslexia in Public Education (New York State)Debra McDade RaffertyAinda não há avaliações

- Technical Assistance Plan 2020Documento2 páginasTechnical Assistance Plan 2020Grethil CamongayAinda não há avaliações

- Magna Carta For Persons With DisabilityDocumento12 páginasMagna Carta For Persons With DisabilityJemarie AlamonAinda não há avaliações

- Prescriptive GrammarDocumento10 páginasPrescriptive GrammarMonette Rivera Villanueva100% (2)

- Materialism: Way of Coping With Stress by AdolescentsDocumento24 páginasMaterialism: Way of Coping With Stress by AdolescentsDominic Manuel E CasausAinda não há avaliações

- Miss Joanna Molabola Grade 6Documento6 páginasMiss Joanna Molabola Grade 6Jinky BracamonteAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Expository Lab DemonstrationDocumento15 páginasPractical Expository Lab DemonstrationCikgu FarhanahAinda não há avaliações

- PR 1 Week 3 and Week 4Documento6 páginasPR 1 Week 3 and Week 4Jaja CabaticAinda não há avaliações

- DLL FBS Week 2Documento4 páginasDLL FBS Week 2MAUREEN DINGALANAinda não há avaliações

- Presented By: Farhan Lakhani Taimur Hasan Syed DurakDocumento17 páginasPresented By: Farhan Lakhani Taimur Hasan Syed DurakAbu BakarAinda não há avaliações

- Unit Planner: (ACELT1581) (ACELT1582) (ACELT1584) (ACELT1586)Documento5 páginasUnit Planner: (ACELT1581) (ACELT1582) (ACELT1584) (ACELT1586)api-464562811Ainda não há avaliações

- Intro To HumanitiesDocumento43 páginasIntro To HumanitiesJozelle Gutierrez100% (1)

- Curriculum Evaluation Is Too Important To Be Left To Teachers DiscussDocumento14 páginasCurriculum Evaluation Is Too Important To Be Left To Teachers DiscussbabyAinda não há avaliações

- Syllabus Fall08Documento55 páginasSyllabus Fall08Rhay NotorioAinda não há avaliações

- DLL - Eng 3rd 8Documento4 páginasDLL - Eng 3rd 8Reesee ReeseAinda não há avaliações

- Patricia Esteves - CVDocumento3 páginasPatricia Esteves - CVapi-297619526Ainda não há avaliações

- 1step Problem DivisionDocumento4 páginas1step Problem DivisionMam NinzAinda não há avaliações

- For Online: Submission of ApplicationDocumento4 páginasFor Online: Submission of ApplicationJeshiAinda não há avaliações

- InterviewDocumento6 páginasInterviewAnonymous r9b4bJU100% (1)

- Reflection Part 4Documento2 páginasReflection Part 4api-213888247Ainda não há avaliações

- Curriculum BasicskillsDocumento1 páginaCurriculum BasicskillsblllllllllahAinda não há avaliações

- EvaluationbymentorteacherDocumento4 páginasEvaluationbymentorteacherapi-299830116Ainda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1TEACHING ENGLISH TO ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTSDocumento6 páginasAssignment 1TEACHING ENGLISH TO ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTSNestor AlmanzaAinda não há avaliações