Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Household Energysources PDF

Enviado por

bentarigan77Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Household Energysources PDF

Enviado por

bentarigan77Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Horticulture and Forestry Vol. 4(2), pp.

43-48, 1 February, 2012

Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JHF

DOI: 10.5897/JHF11.071

ISSN 2006-9782 2012 Academic Journals

Full Length Research Paper

Analysis of household energy sources and woodfuel

utilisation technologies in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa

districts of Central Kenya

Githiomi J. K.1*, Mugendi D. N.2 and Kungu J. B.2

1

Forest Products Research Centre, Kenya Research Institute, P.O. Box 64636-00620 Nairobi, Kenya.

Department of Environmental Sciences, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, Kenya.

Accepted 29 December, 2011

This study was carried out in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts of Central Kenya. Its objective was

to analyze household energy sources and utilization technologies used. Primary data was collected

from households using structured and non structured questionnaires. Trees on farm were found to be

the major supply of the woodfuel energy where firewood was the main source of household energy

followed by charcoal. Traditional three stones stoves were the most commonly used with 76 59 and 65

(household respondents) in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts respectively. Improved charcoal

stoves were the second commonly used while only a very negligible percentage used kerosene stoves

and gas burners. Over 70% of the respondents were aware of the improved stoves but their adoption

was less than 29%. The low adoption of improved stoves was due to their high cost as noted by the

respondents. Over 90% of the households had the opinion that woodfuel sources were decreasing and

there was a need to develop strategies for its future sustainability. The study recommended integration

of woodfuel production to local farming systems and establishment of fuelwood plantations by Kenya

Forest Service to substitute on farm sources. It also recommended promotion of improved stoves with

higher efficiency to reduce the woodfuel used as well as improve on environmental pollution.

Key words: Farmlands, Central Kenya, improved stoves, firewood, charcoal.

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that about 90% of Kenyan rural

households use woodfuel either as firewood or charcoal

(MoE, 2002) and it provides income to over 3 million

people (ESDA, 2005). A significant portion of the rural

population is employed in wood energy trade and it

constitutes a major source of energy in Kenya (Republic

of Kenya, 2002a). The Government of Kenya has been

involved in promoting tree planting at the farm level with

the aim of increasing tree cover to 10% by the year 2030

(Republic of Kenya, 2007). There have been successful

tree planting programs involving rural communities in

Kenya led by government rural forest extension services

and various non governmental organizations (NGOs).

*Corresponding author. E-mail: josephgithiomi@ymail.com. Tel:

254 -722496795.

Green Belt Movement is among the most active NGOs

which have assisted planting of over 45 million trees in

different parts of Kenya for the last three decades.

Besides being the standard cooking fuel for the majority

of Kenyan households, fuelwood is also an important

energy source for small-scale rural industries such as

tobacco curing, tea drying, brick making, fish smoking,

and bakeries, among others. However, despite its

importance, the available data is scarce and uncertain

which is mainly due to the fact that it is handled in the

informal sector and does not pass through monetized

economy like in the case of liquefied petroleum gas

(LPG), kerosene and electricity which are alternatives to

wood energy. The energy sector concentrates more on

national energy planning for conventional fuels while

forestry sector focus more on planning for commercial

wood supply and conservation of protected areas

(Republic of Kenya, 2002a). These two key sectors deny

44

J. Hortic. For.

Figure 1. Map of the study area showing the Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

biomass energy the comprehensive consideration it

deserves due to the role it plays in supply of energy to

majority of Kenyans.

This study was undertaken between 2006 and 2007

and it was aimed at establishing household energy sources and its utilization technologies in Kiambu, Thika and

Maragwa districts of Central Kenya. The data obtained is

useful in policy formulations in these three districts.

METHODOLOGY

This study was carried out in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts

of Central Kenya as shown in Figure 1. The districts were

purposively sampled on the basis of various factors which include

diverse wood production systems (farmlands, plantations, and

natural forests), diverse ecological conditions and population

densities among others. The selected districts had rainfall range

from 800 to 1400 mm, 500 to 2500 mm and 900 to 2700 mm for

Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts respectively (Republic of

Kenya, 1997a, b, 2002b). Sampling of the households was done

using multistage stratified random sampling technique beginning

with stratification sampling procedures as outlined by Lee-Ann and

Martin (1997). Each of the three districts under study was stratified

according to the weights in socio-economic and climatic activities as

indicators. Following this procedure, at least 40% of the divisions

with relatively homogeneous characteristics in each district were

sampled. This ensured that heterogeneity was well captured and

represented. Similar procedure was followed for selection of administrative locations and sub-locations. Based on these sampling

procedures, Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts were stratified

into four, three and two strata respectively. Each stratum in the

district consisted of one or more divisions. A total of 200 households were sampled from each district. Allocation of the sampling

units in each selected division was done proportionally to the total

number of household obtained from the 1999 census (Republic of

Kenya, 2001).

The data collection was done using structured and semistructured household questionnaires which captured data on the

source of woodfuel, supply trend, the type of energy sources used,

cooking technologies and awareness on the improved stoves. The

generated data was coded and entered in the computer using

spread sheet MS-Excel. Statistical package for social sciences

(SPSS) was used in analyzing the data.

Githiomi et al.

45

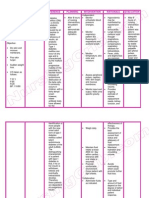

Table 1. Sources of woodfuel in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

District

Kiambu

Thika

Maragwa

Indigenous trees

scattered on farm

%

n

4

8

26

50

40

80

Percentage responses on supply sources of woodfuel

Exotic trees scattered Planted

Purchase

Gazetted

on farm

woodlots from vendors

forests

%

n

%

n

%

n

%

n

24

49

4

9

57

117

9

18

12

22

3

6

57

109

1

1

31

63

21 42

5

10

2

4

Others

%

2

3

1

n

4

3

1

Total

%

n

100 205

100 191

100 200

Table 2. Responses on supply trend of woodfuel sources in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

Supply trend of woodfuel from different sources

District

Source of woodfuel

Kiambu

Existing scattered indigenous trees on farms

Existing exotic scattered trees on farm

Planted woodlots

Purchase from sellers

Gazetted forests

Others

%

33

7

33

3

0

0

n

2

3

1

2

0

0

%

67

93

67

97

100

100

n

4

39

2

67

18

3

%

100

100

100

100

100

100

n

6

42

3

69

18

3

Thika

Existing scattered indigenous trees on farms

Existing exotic scattered trees on farm

Planted woodlots

Purchase from sellers

Gazetted forests

Others

13

14

50

37

0

0

6

3

3

29

0

0

87

86

50

63

100

100

41

18

3

50

12

3

100

100

100

100

100

100

47

21

6

79

12

3

Maragwa

Existing scattered indigenous trees on farms

Existing exotic scattered trees on farm

Planted woodlots

Purchase from sellers

Gazetted forests

Others

4

19

2

10

0

0

3

11

1

1

0

0

96

81

98

90

100

100

70

47

40

9

11

2

100

100

100

100

100

100

73

58

41

10

11

2

RESULTS

The results on the woodfuel supply sources in the three

districts under study (Table 1) showed that majority of the

respondents from Kiambu and Thika districts (57%)

purchased woodfuel from vendors whereas others

obtained woodfuel directly from the farm. The woodlots

were taken as an area in the farm set aside for tree

planting while the other trees in the farm were either

referred to as scattered indigenous or exotic. Maragwa

district had the highest number of households sourcing

woodfuel from indigenous trees scattered on farm. In

Maragwa and Thika districts, there were less than 2% of

the households sourcing woodfuel from the gazetted

forests. Charcoal was the main product purchased from

Increase

Decrease

Total

vendors as firewood was mainly sourced directly from the

farms. Overall, there was a significant difference

(2=157.852; d.f=2; p<0.01) among districts in terms of

supply sources of wood energy.

The households response to the trend of future supply

sources which included existing scattered indigenous

trees on farms, existing exotic scattered trees on farm,

planted woodlots, gazetted forests and purchases from

vendors showed a decrease in all woodfuel supplies

sources (Table.2). Majority of the household respondents

in Kiambu and Thika districts indicated that the purchase

of woodfuel from sellers will decrease as compared to

Maragwa who had the highest number (73) indicating the

highest decrease was to be in existing scattered indigenous trees on farms which was also their main source of

46

J. Hortic. For.

Table 3. Sources of energy used by households in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

District

Firewood

%

n

87

181

80

159

96

192

Kiambu

Thika

Maragwa

Charcoal

%

n

12

25

15

30

1

2

Commonly used sources of energy

Kerosene

Gas

Crop residue

%

n

%

n

%

n

1

1

1

2

0

0

4

7

1

2

1

1

2

4

1

1

1

1

Total

%

n

100

209

100

199

100

200

Table 4. Cooking technology devices used in Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

Response on each technology used

District

Kiambu

Thika

Maragwa

Three

stone fire

Traditional

metal stove

Improved charcoal

stove

Kiambu

Thika

Maragwa

Kerosene

stove

Gas burner

Total

76

59

64

155

116

130

4

2

6

8

4

12

18

30

24

36

59

49

0.5

2

3

1

3

7

0.5

5

1

1

9

1

1.0

2

2

2

3

4

100

100

100

203

198

203

Table 5. Awareness of improved technology in Kiambu, Thika

and Maragwa districts.

District

Improved firewood

stove

Aware

%

n

79

162

70

136

89

177

Not aware

%

no

21

42

30

59

11

23

Total

%

n

100

204

100

195

100

200

Table 6. Reasons for not using improved firewood stoves in

Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts.

Reasons for not

using improved

firewood stoves

Kiambu

%

n

Cost

31

56

Non availability

23

41

Not interested

34

62

Never heard of it

7

12

10

Very slow in cooking 5

Total

100 181

Respondents

Thika

%

n

25 31

35 43

22 27

15 19

3

3

100 123

Maragwa

%

n

57 74

16 21

14 18

12 16

1

1

100 130

source of woodfuel. The results showed that there were

significant differences (p<0.01) in the sources of energy

used by households within the districts studied.

Firewood was commonly used as shown by 87, 80 and

96% of the households respondents in Kiambu, Thika

and Maragwa districts respectively followed by charcoal.

Crop residue, gas and kerosene were the least used

(Table 3). The average weekly firewood and charcoal

consumption per household in the three districts was

found to be 32 and 10.4 kg respectively.

The results of woodfuel utilisation technologies are

shown in Table 4. Inferential analysis of the data showed

that there were significant differences (p<0.01) among

technologies used within each district where three stones

was the most commonly used by the household

respondents with 76, 59 and 64% followed by improved

charcoal stove with 18, 30 and 24% in Kiambu, Thika and

Maragwa districts respectively. A very negligible

household percentage used kerosene stoves and gas

burners.

On the awareness of the improved technology, the

results (Table 5) showed that over 70% of the respondents were aware of improved cooking technologies. This

2

significantly varied among the districts ( =21.162; d.f=2;

p<0.00) where majority were from Maragwa district

followed by Kiambu. The adoption of improved charcoal

and fire wood stoves was 19, 24.5 and 28% in Kiambu,

Thika and Maragwa districts, respectively.

A number of reasons were cited for not using the

improved stoves with cost of purchasing improved stoves

being regarded as main reason for its non-adoption

(Table 6). This was significantly different (p<0.05) across

the three districts but it was highly pronounced in

Maragwa followed by Kiambu district. Other factors that

cause non adoption of these improved stoves are their

non availability, and lack of awareness by potential users.

DISCUSSION

The significant difference among districts in terms of

supply sources of wood energy implied that each supply

sources of woodfuel had different weights in each district.

Githiomi et al.

For example, Maragwa got its woodfuel mainly from

scattered indigenous trees on farm as compared to Thika

and Kiambu who purchase mainly from vendors. The

study indicated that farmlands form a critical part of wood

energy resource supply as observed in all districts and

only a small proportion of household were sourcing

woodfuel from the gazzeted forests. Similar observations

were reported by Ministry of Energys study on energy

supply and demand for household, small scale industries

and service establishment in Kenya where most woodfuel

was found to be from the farmlands (MoE, 2002).

Encouraging farmers to plant more trees could increase

the supply of woodfuels and other wood products considerably within the study area. However, there is limitation

in promoting woodfuel production as it is taken as a byproduct of other activities (like timber) which are more

valued.

The decreasing trend of major supply sources in the

three districts was caused by scarcity of land for

continuous tree planting, deforestation of gazetted and on

farm forests and slow maturity of indigenous tree species.

These constraints can be addressed through planting of

fast growing species and adopting planting technologies

that maximizes the woodfuel production in agroforestry

systems. The decreased supply of woodfuel supports the

need for wood energy planning in each of the study

districts to avoid eminent deficit.

The high number of household residents using firewood

as source of energy (over 80%) had also been observed

in a study by Ministry of Energy on energy demand and

supply for households where 89% of rural households

were found to be using firewood countrywide (MoE,

2002). This also compares well with another study by

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics which indicated that

87.7% of households in Kenya were using firewood

(Ministry of Planning and National Development, 2007).

On-farm tree planting has a significant role to play in

woodfuel production in Kenya. The government of Kenya

has promoted tree planting on farm and in gazetted

forests through the Kenya Forestry service and several

other projects by development partners and NGOs. Tree

reforestation has been done in degraded areas like Mau

forest and other Kenyan water towers.

The three stone stoves which were commonly used in

the three districts despite having low efficiency of about

10% and high health hazards, however, are popular with

the households as they are cheap and they also

contribute to house warming. The reported percentages

(59 to 76%) of the households respondents using three

stone stoves are lower than what was reported in a study

by Mugo (1999a) on rural households, but the variation

could be due to the fact that this current study considered

both rural and urban centres.

The proportion of households aware of the improved

cooking technology was over 70% in all the districts.

However, despite this high awareness, majority of the

respondents were using the three stone stoves and only

47

a small proportion of less than 28% of the household

respondent had adopted the improved charcoal and

firewood stoves which was much lower than 47%

reported in a study on Kenyas energy demand and

supply for households by Ministry of Energy (MoE, 2002).

The difference in adoption among the districts could be

due to variation in household income among the three

districts. In Maragwa district, the improved stove

awareness was higher than the other districts as there

was an NGO which had been promoting improved

stoves. This could be the reason why the district also had

relatively higher rate of adoption of improved stoves

compared to the other two districts. It is known that three

stone stoves consume a lot of firewood as they are not

efficient and they emit several serious pollutants which

cause health problems (Kirk, 1993; Pandey, 1997). The

improved stoves need to be promoted as they use less

woodfuel and have higher combustion efficiency which

gives greater amount of heat and less smoke. The use of

improved stoves will lead to reduced environmental

related diseases as outlined in Kenya vision 2030. In

addition, the use of improved stoves will also reduce the

rate of deforestation and environmental degradation

(Mugo, 2001). The use of less fuelwood by improved

stoves also reduces the time used in fuelwood collection,

which can be re-directed into other income generating

activities. There is need for further sensitization on the

importance of using improved stoves as most of those

who were aware about them were not using them. The

main reason for the low adoption of these stoves was

their higher cost which can be reduced through facilitation

of their production at the local level.

Some of the improved stoves that have been adopted

in Kenya and the neighboring countries of East and

Central Africa include Kenya Ceramic Jiko (KCJ). This is

a simply traditional charcoal metal stove fitted with

ceramic liner which increases its efficiency several times

as compared to the traditional all metal alternative. The

other stove which has been successfully produced by

local women groups in western Kenya is the Upesi stove

which also has simple molding of clay liner.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The woodfuel supply trend indicated that it was

decreasing and therefore there is need to integrate its

production with local farming systems as agricultural

sector has a key role to play in supplementing woodfuel.

This can be supported through development of on-farm

management regimes for use at the farm level to ensure

sustainability of woodfuel production. The Kenya Forest

Service should also develop plantations for woodfuel

production as a national priority as it does with timber

production. The firewood plantations should be established with appropriate fast growing trees which match

specific environmental and ecological conditions for

48

J. Hortic. For.

maximum productivity.

The conservation of wood energy should be given a

priority through promotion of improved stoves with higher

efficiency as it was found that over 70% of the households in the study area use three stone stoves which

were inefficient. The improved stoves to be promoted for

adoption should consider users needs which include

cooking comfort, convenience, health and safety. The

improved stoves should also be of affordable prices as it

was noted in this study that low adoption of improved

woodfuel cooking devices was contributed by their high

cost. This can be achieved through building capacity of

making improved stoves at local level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the District Forest

Officers of Kiambu, Thika and Maragwa districts for

assisting in data collection and KEFRI management for

supporting the study.

REFERENCES

ESDA (2005). National Charcoal Survey: Exploring the potential for

sustainable charcoal industry in Kenya. Energy for Sustainable

Development Africa, Nairobi, Kenya. p 79.

Kirk RS (1993). Wood energy health effects in developing countries.

Paper presented at seminar on policy instruments for wood energy

development held in May 1993, Bankok, Thailand. p 4.

Lee-Ann CH, Martin AB (1997). Surveying Natural Population. Columbia

University Press, New York, pp.113-152.

Ministry of Energy (2002). Study on Kenyas Energy Demand, Supply

and Policy Strategy for Households, Small scale Industries and

Service Establishments. Kamfor Consultants, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 133

Ministry of Planning and National Development (2007). Kenya

integrated household budget survey 2005/06 Revised Edition. KNBS,

Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 96

Mugo F (1999). The effect of fuelwood demand and supply

characteristics, land factors and gender on tree planting and

fuelwood availability in highly populated rural areas of Kenya. A PhD

dissertation, Cornell University, New York, USA, pp. 7.

Mugo FW (2001). The role of woodfuel conservation in sustainable

supply of the resource: The case for Kenya. Paper presented at

charcoal stakeholders workshop held at World Agroforestry Centre

th

(ICRAF), 15 October, 2001, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 4.

Pandey MR (1997). Women, Wood Energy and Health. Wood Energy

News, Food and Agriculture Organization-Regional Wood Energy

Development Programme in Asia (FAO-RWEDP), Bangkok,

Thailand, 12(1):3-5

Republic of Kenya (1997a). Kiambu District Development Plan.

Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 156.

Republic of Kenya (1997b). Thika District Development plan 2002-2008.

Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 165.

Republic of Kenya (2001). 1999 Population and Housing Census:

Counting our people for development. Government Printers, Nairobi,

Kenya, pp. 157.

Republic of Kenya (2002a). National Development Plan 2002-2008:

Effective Management for Sustainable Economic Growth and Poverty

Reduction. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 79.

Republic of kenya (2002b). Maragwa District Development Plan 20022008: Effective Management for Sustainable Economic Growth and

Poverty Reduction. Government Printers, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 359.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Forklift Driver Card and Certificate TemplateDocumento25 páginasForklift Driver Card and Certificate Templatempac99964% (14)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Nursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1Documento2 páginasNursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1deric85% (46)

- Final Report of BBSMDocumento37 páginasFinal Report of BBSMraazoo1967% (9)

- Syllabus EM1Documento2 páginasSyllabus EM1Tyler AnthonyAinda não há avaliações

- Thermal Analysis of Refrigeration Systems Used For Vaccine StorageDocumento41 páginasThermal Analysis of Refrigeration Systems Used For Vaccine Storagebentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- 30 Watts Portable Thermoelectric Power GeneratorDocumento3 páginas30 Watts Portable Thermoelectric Power Generatorbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Break Even and Optimization Analysis: Stephana Dyah Ayu R.,Se.,Msi.,AktDocumento29 páginasBreak Even and Optimization Analysis: Stephana Dyah Ayu R.,Se.,Msi.,Aktbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- John Eggink - Managing Energy CostsDocumento19 páginasJohn Eggink - Managing Energy Costsbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Brijesh PDFDocumento2 páginasBrijesh PDFbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Petunjuk Pengisian Form Progress ReportDocumento2 páginasPetunjuk Pengisian Form Progress Reportbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Batch Process Solar Disinfection Is An Efficient Means of Disinfecting Drinking Water Contaminated With Shigella Dysenteriae Type IDocumento5 páginasBatch Process Solar Disinfection Is An Efficient Means of Disinfecting Drinking Water Contaminated With Shigella Dysenteriae Type Ibentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Ssessing The Effectiveness of Social Marketing: Jude VarcoeDocumento13 páginasSsessing The Effectiveness of Social Marketing: Jude Varcoebentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Production of Wood FuelsDocumento4 páginasProduction of Wood Fuelsbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Dave and MaheshDocumento5 páginasDave and Maheshbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- LF-6 Puzzle Word CardsDocumento10 páginasLF-6 Puzzle Word Cardsbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Arch Dis Child 2001 Conroy 293 5Documento4 páginasArch Dis Child 2001 Conroy 293 5bentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Soca-Suharyanto-Permintaan Daging SapiDocumento14 páginasSoca-Suharyanto-Permintaan Daging Sapibentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Widening Access To Rural Energy Services in Africa: Looking To The FutureDocumento6 páginasWidening Access To Rural Energy Services in Africa: Looking To The Futurebentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- 1 Actual Expansion Isentropic Expansion - H - HDocumento1 página1 Actual Expansion Isentropic Expansion - H - Hbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Book Review: Social Marketing: Improving The Quality of Life. Philip KotlerDocumento1 páginaBook Review: Social Marketing: Improving The Quality of Life. Philip Kotlerbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- ReferenceDocumento1 páginaReferencebentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- + Addition + Addition - Subtraction X Multiplication ÷ DivisionDocumento1 página+ Addition + Addition - Subtraction X Multiplication ÷ Divisionbentarigan77Ainda não há avaliações

- Moodle2Word Word Template: Startup Menu: Supported Question TypesDocumento6 páginasMoodle2Word Word Template: Startup Menu: Supported Question TypesinamAinda não há avaliações

- CE - 441 - Environmental Engineering II Lecture # 11 11-Nov-106, IEER, UET LahoreDocumento8 páginasCE - 441 - Environmental Engineering II Lecture # 11 11-Nov-106, IEER, UET LahoreWasif RiazAinda não há avaliações

- Syncretism and SeparationDocumento15 páginasSyncretism and SeparationdairingprincessAinda não há avaliações

- Rawtani 2019Documento9 páginasRawtani 2019CutPutriAuliaAinda não há avaliações

- Applications Description: General Purpose NPN Transistor ArrayDocumento5 páginasApplications Description: General Purpose NPN Transistor ArraynudufoqiAinda não há avaliações

- File Server Resource ManagerDocumento9 páginasFile Server Resource ManagerBùi Đình NhuAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3Documento26 páginasChapter 3Francis Anthony CataniagAinda não há avaliações

- The Status of The Translation ProfessionDocumento172 páginasThe Status of The Translation ProfessionVeaceslav MusteataAinda não há avaliações

- Boomer L2 D - 9851 2586 01Documento4 páginasBoomer L2 D - 9851 2586 01Pablo Luis Pérez PostigoAinda não há avaliações

- Study of Noise Mapping at Moolchand Road Phargang New DelhiDocumento10 páginasStudy of Noise Mapping at Moolchand Road Phargang New DelhiEditor IJTSRDAinda não há avaliações

- PostmanPat Activity PackDocumento5 páginasPostmanPat Activity PackCorto Maltese100% (1)

- How Plants SurviveDocumento16 páginasHow Plants SurviveGilbertAinda não há avaliações

- Manipulation Methods and How To Avoid From ManipulationDocumento5 páginasManipulation Methods and How To Avoid From ManipulationEylül ErgünAinda não há avaliações

- Interdisciplinary Project 1Documento11 páginasInterdisciplinary Project 1api-424250570Ainda não há avaliações

- 08 - Chapter 1Documento48 páginas08 - Chapter 1danfm97Ainda não há avaliações

- New Arrivals 17 - 08 - 2021Documento16 páginasNew Arrivals 17 - 08 - 2021polar necksonAinda não há avaliações

- Warranties Liabilities Patents Bids and InsuranceDocumento39 páginasWarranties Liabilities Patents Bids and InsuranceIVAN JOHN BITONAinda não há avaliações

- C MukulDocumento1 páginaC Mukulharishkumar kakraniAinda não há avaliações

- Empowerment TechnologyDocumento2 páginasEmpowerment TechnologyRegina Mambaje Alferez100% (1)

- Sponsor and Principal Investigator: Responsibilities of The SponsorDocumento10 páginasSponsor and Principal Investigator: Responsibilities of The SponsorNoriAinda não há avaliações

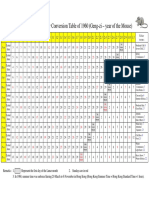

- Gregorian-Lunar Calendar Conversion Table of 1960 (Geng-Zi - Year of The Mouse)Documento1 páginaGregorian-Lunar Calendar Conversion Table of 1960 (Geng-Zi - Year of The Mouse)Anomali SahamAinda não há avaliações

- Class XI-Writing-Job ApplicationDocumento13 páginasClass XI-Writing-Job Applicationisnprincipal2020Ainda não há avaliações

- Development and Application of "Green," Environmentally Friendly Refractory Materials For The High-Temperature Technologies in Iron and Steel ProductionDocumento6 páginasDevelopment and Application of "Green," Environmentally Friendly Refractory Materials For The High-Temperature Technologies in Iron and Steel ProductionJJAinda não há avaliações

- Water Quality MonitoringDocumento3 páginasWater Quality MonitoringJoa YupAinda não há avaliações

- Prince Ryan B. Camarino Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonDocumento2 páginasPrince Ryan B. Camarino Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonKyle Aureo Andagan RamisoAinda não há avaliações

- CSMP77: en Es FRDocumento38 páginasCSMP77: en Es FRGerson FelipeAinda não há avaliações