Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

COUTIN - Denationalization Inclusion and Exclusion

Enviado por

João BorgesDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

COUTIN - Denationalization Inclusion and Exclusion

Enviado por

João BorgesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Indiana Journal of Global Legal

Studies

Volume 7 | Issue 2

Article 8

4-1-200

Denationalization, Inclusion, and Exclusion:

Negotiating the Boundaries of Belonging

Susan B. Coutin

California State University, Los Angeles

Recommended Citation

Coutin, Susan B. (2000) "Denationalization, Inclusion, and Exclusion: Negotiating the Boundaries of Belonging," Indiana Journal of

Global Legal Studies: Vol. 7: Iss. 2, Article 8.

Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol7/iss2/8

This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law

School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted

for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized

administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information,

please contact wattn@indiana.edu.

Denationalization, Inclusion, and Exclusion:

Negotiating the Boundaries of Belonging

SUSAN

B. COUTIN"

While volunteering in the offices of a Central American community

organization in Los Angeles in September, 1999, 1 sat looking at the small box

that presented itself on a computer screen in front of me. "Part 7.

Information about your PARENT/PARENTS. Citizenship." "And your father

was a Guatemalan citizen?" I bothered to ask. The man across the desk

stared at me. I was helping him complete an application for U.S. residency

under the terms of the 1997 Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American

Relief Act (NACARA).' He had just told me his father's name and place of

birth (Guatemala City), and had tried unsuccessfully to recall his father's

birthdate. "Yes," the man answered, in an "of course" tone of voice. Feeling

a bit foolish, I mentally justified my question. People move. They change

citizenship. And citizenship is sometimes ambiguous. I recalled that an

attorney had once told me that even he could not figure out whether his client,

who had two birth certificates, was Salvadoran or Honduran. As I continued

filling out the man's application, I came to the questions about his mother.

Despite my mental justifications, this time I simply said, "And your mother, of

course, is Guatemalan."

The incongruity between the assumptions that placed this citizenship

question on a U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service form and the

applicant's seeming surprise at being asked his father's citizenship is at least

partially explained by Linda Bosniak's provocative discussion of the

denationalization of citizenship. Bosniak notes that citizenship has at least four

dimensions: (1) legal status, (2) rights, (3) political activity, and (4) collective

* Susan Bibler Coutin, Assistant Professor, California State University-Los Angeles.

She

is the author of LEGALIZING MOVES: SALVADORAN IMMIGRANTS' STRUGGLE FOR U.S. RESIDENCY

(2000) [hereinafter LEGALIZING MOVES] and THE CULTURE OF PROTEST: RELIGIOUS ACTIVISM

AND THE U.S. SANCTUARY MOVEMENT (1993).

1. NACARA created an "amnesty" for Nicaraguans who were beneficiaries of the Nicaraguan

Review Program and permitted some 300,000 Salvadorans and Guatemalans to apply for suspension

of deportation, an immigration remedy that had been eliminated by the Illegal Immigration Reform

and Immigrant Responsibility Act in 1996. See Susan Bibler Coutin, From Refugees to Immigrants:

The Legalization Strategies of Salvadoran Immigrants and Activists, 32 INT'LMIGRATION REV. 901

(1998). See also SUSAN BIBLER COI'rIN, LEGALIZING MOVES supra note *.

586

INDIANA JOURNAL OF GLOBAL LEGAL STUDIES

[Vol. 7:585

identity.2 From a legal standpoint, the applicant's parents' citizenship is

significant. To obtain U.S. residency through NACARA, the applicant who

I was assisting had to demonstrate that deportation would be an extreme

hardship to him, or to a legal permanent resident, or to a U.S. citizen relative.

If his parents were citizens or legal permanent residents of the United States,

then their legality would confer a "right" of sorts, on this applicant. He could

argue that he had family ties in the United States, and that being deported

would disrupt those ties, thus creating an extreme hardship for both the

applicant and his parents. In addition, the applicant's parents would have the

right to submit a family visa petition on his behalf, thus opening another

immigration avenue should his NACARA application be delayed or denied.

At the same time, this applicant's unsuccessful effort to recall his father's

birthdate had evoked a social reality in which the facts that are requested on

immigration forms-birthdates, alien numbers, financial assets-are unimportant.

Having evoked this social reality, the question that defined the applicant's

father solely in terms of legal status seemed particularly reductionistic.

Both this anecdote and Bosniak's article draw attention to the

contradictions inherent in institutionalizing categories that nationalize citizenship,

even as the realities that privilege State-based definitions of citizenship are

transformed. Individuals who have been excluded from State membership live

these contradictions. This Comment on Bosniak's article examines these

contradictions in order to consider the danger and value of denationalization for

those who have been excluded.

As Bosniak notes, citizenship is a legitimizing term: "To describe a set of

social practices in the language of citizenship serves to legitimize them and

grant them recognition as politically consequential, while to refuse them the

designation is to deny them that recognition." 3 If citizenship is key to

legitimation, and if immigration "gatekeepers"' link citizenship inextricably to

the nation-State, then to practice denationalized forms of citizenship is to risk

being defined as illegitimate. At the same time, those who are denied formal

membership must develop other, often informal and extrastatal, forms of

membership, 5 including: living and working in a country in which one lacks

2. Linda Bosniak, CitizenshipDenationalized,7 IND. J. GLOBAL LEGAL STUD.

447, 455

(2000).

3. Id. at 452-53.

4. TOMAS HAMMAR, DEMOCRACY AND THE NATION STATE: ALIENS, DENIZENS AND CITIZENS

IN A WORLD OF INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION (1990).

5. Tomas Hammar, Legal Time of Residence and the Status of Immigrants, inFROM ALIENS

TO CITIZENS:

REDEFINING THE STATUS OF IMMIGRANTS IN EUROPE 187-197 (Rainer Baubock ed.,

2000]

DENATIONALIZATION, INCLUSION, AND EXCLUSION

587

legal status, participating in transnational networks, and acting as a citizen of

something other than a State. The multiple dimensions of citizenship give rise

to strategies for legitimizing informal or extrastatal forms of membership.

Thus, unauthorized immigrants who demonstrate civic involvement, social

deservedness, and national loyalty can argue that they merit legal residency.

In other words, individuals can move between the multiple meanings of

citizenship, using one dimension to confer another. Similarly, to term

membership in nonnational communities, organizations, and groupings as

"citizenship" is to legitimize these entities. Movements between membership

and exclusion, one dimension of citizenship and another, the national and the

nonnational, and legitimacy and illegitimacy, may be as important as

redefinitions of citizenship itself.

The Salvadoran immigrants I interviewed in Los Angeles between 1995

and 1997 were well aware of the legitimizing nature of citizenship. Many

Salvadorans who entered the United States during the 1980s and early 1990s

did so without visas and therefore became undocumented immigrants. Their

lack of legal residency was a "deeply exclusionary" experience.' One

Salvadoran activist complained to me during an interview, "We need to be here

legally or it's like we're not here." Similarly, a formerly undocumented

community college student noted that, without a work permit, "you don't exist.

Well, they know you are there, but they ignore you. They don't see you as like

you exist. And this is the people who raise children, and you know, whenever

they come, [other people say,] 'Well, they're illegals."' 7 According to these

comments, despite performing such useful tasks as raising children,

undocumented immigrants are excluded through policies that define wage

labor-a key marker of presence, personhood, and citizenship 8 -as a privilege

that States can either grant or deny to particular categories of persons. 9

Because they lack authorization, the undocumented can only work

clandestinely.

1994).

6. Bosniak, supra note 2, at 503.

7. Interview with research participant, Aug. 17, 1997,

omitted for reasons of confidentiality.

Interviewees' names have been

8. David M. Engel & Frank W. Munger, Rights, Remembrance, and the Reconcilation of

Difference, 30 L. & SOC'Y REv. 7; ROBERT J. THOMAS, CITIZENSHIP, GENDER, AND WORK: SOCIAL

ORGANIZATION OF INDUSTRIAL AGRICULTURE (1985).

9. See Linda S. Bosniak, Human Rights, State Sovereignty and the Protection of

Undocumented Migrants Under the International Migrant Workers Convention, 25 INT'L

MIGRATION REV. 737 (1991).

588

INDIANA JOURNAL OF GLOBAL LEGAL STUDIES

[Vol. 7:585

Low wages problematize unofficial workers' material existence, while lack

of employment records impedes legal recognition of their physical and temporal

presences. Undocumented workers labor in sweatshops, fields, homes, and

elsewhere, often in conditions that violate federal and state labor codes. The

undocumented are further excluded by policies that make their family ties

legally inert for immigration purposes. Lacking legal status themselves,

undocumented immigrants cannot petition for the legalization of their parents

or other relatives. Nor do they have the right to leave and reenter the United

States so that they can visit relatives abroad. Lacking travel documents, their

entries and exits are clandestine. Instead of petitioning for relatives (as legal

citizens can), they smuggle them into the country. Finally, the unauthorized are

excluded through practices that limit their mobility. Subjected to detention and

deportation ifapprehended, the undocumented avoid areas where they might

encounter U.S. immigration officials. One Guatemalan migrant characterized

this situation as "democracy with a stick."' 0 He explained: "If you are illegal,

you don't have freedom of movement. You go from your workplace to your

house and as much as possible you avoid contact with the authorities."' I

Excluded from formal membership in their countries of residence,

undocumented immigrants develop covert, informal, and often extrastatal

strategies and networks. Undocumented immigrants exchange information

about job opportunities, 12 sometimes even recruiting workers from their

hometowns. 3 Migrants look to friends, family, and former neighbors for

assistance in finding housing, surviving a period of unemployment, or bringing

another relative into the country. Migrant communities in the United States

also feature illicit and quasi-illicit services, such as document forgers,

unlicensed legal practitioners, 4 and money changers. Employers who hire

unauthorized workers also participate in these networks.'" Covert networks

take transnational form, with migrants' hometowns relying on remittances from

migrant workers, migrant workers depending on hometown kin for dependent

6

care, and employers utilizing migrant networks to fill labor needs.

10. Interview with research participant, Oct. 7, 1996, Los Angeles.

11. Id.

12. HECTOR DELGADO, NEW IMMIGRANTS, OLD UNIONS: ORGANIZING UNDOCUMENTED

WORKERS IN LOS ANGELES (1993).

13. JACQUELINE MARIA HAGAN, DECIDING TO BE LEGAL: A MAYA COMMUNITY IN HOUSTON

(1994).

14. SARAH J. MAHLER, AMERICAN DREAMING: IMMIGRANT LIFE ON THE MARGINS (1995).

15. Kitty Calavita, Employer Sanctions Violations: Toward a Dialectical Model of WhiteCollar Crime, 24 L. AND SOC'Y REV. 1041 (1990).

16. HAGAN, supra note 13; Michael Kearney, The Effects of Transnational Culture, Economy,

2000]

DENATIONALIZATION, INCLUSION, AND EXCLUSION

589

Salvadorans have also developed transnational political organizations, ranging

from refugee committees to committees in support of factions of theFrente

FarabundoMartiparala Liberaci6n Nacional (FMLN), the coalition that

opposed the Salvadoran government during the civil war. 17 In the past, these

transnational political organizations have funneled financial and military support

to the guerrillas during the 1981-92 Salvadoran civil war, provided services to

refugees who sought shelter in the United States, opposed U.S. intervention in

El Salvador, and advocated refugee status or other forms of legal residency for

Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants. Through such formal and informal

transnational networks, undocumented immigrants could evade state authorities

and official practices. These nonnational and clandestine groupings and

activities enable undocumented immigrants to use one dimension ofcitizenship

18

to confer another.

Individuals who lack formal State membership nonetheless participate

informally in society. U.S. immigration law recognizes such informal

participation as grounds for conferring legal residency. Prior to 1996,

individuals who could prove seven years of continuous presence, good moral

character, and that deportation would be an extreme hardship, were eligible for

suspension of deportation, and thus, U.S. residency. NACARA extended

suspension eligibility to some 300,000 Salvadorans and Guatemalans, including

the man whose application I was preparing in September, 1999.

Demonstrating attachment to the United States, participating in civic activities

(such as volunteer work), and developing strong community ties (the nonlegal

dimensions of citizenship) are means of proving extreme hardship and thus

obtaining legal residence. Such claims are grounded in what some have

described as an implicit contract between migrant workers and the States in

which their labor is employed. 19 According to this implicit contract, when

migrants contribute to a society through their labor, the society incurs certain

obligations to migrants, such as the obligation to recognize them as full social

and legal persons. Through various forms of social participation (going to

school, forming a family, obtaining an address, working), migrants imitate

and Migration on Mixtec Identity in Oaxacalifornia, in THE BUBBLING CAULDRON:

ETHNICITY, AND THE URBAN CRISIS 226 (Michael Peter Smith & Joe R. Feagin eds., 1995).

RACE,

17. See generally HUGH BYRNE, EL SALVADOR'S CIVIL WAR: A STUDY OF REVOLUTION,

(1996); COUTIN, supra note I; TOMMIE SUE MONTGOMERY, REVOLUTION IN EL SALVADOR: FROM

CIVIL STRIFE TO CIVIL PEACE (2d ed. 1995).

18. This process can also work in reverse. A denial of, or failure in, one dimension of

citizenship (e.g., collective sentiment) can also justify exclusion from others (e.g., legal status).

19. Bosniak, supra note 9; Hammar, supra note 5; PUBLIC CULTURE BOOK, CITIES AND

CITIZENSHIP (James Holston ed., 3d ed. 1999).

590

INDIANA JOURNAL OF GLOBAL LEGAL STUDIES

[Vol. 7:585

citizens and thus act on the rights that this implied contract promises.2" The

informal and somewhat underground networks that enable undocumented

migrants to survive can thus create grounds for legalization.

The use of one dimension of citizenship to acquire another occurs in

migrants' relationships to their countries of origin as well. During the 1981-92

civil war, Salvadoran migrants were directly and indirectly excluded from El

Salvador through political violence, economic devastation, and direct

persecution. Although migrants were legal citizens of El Salvador, they were

not guaranteed the practical rights (residency, political participation, and

freedom from persecution) accorded by their citizenship. After leaving El

Salvador, many migrants continued to provide financial support to their families

and home communities. By the 1990s, emigrd remittances had become a

mainstay of the Salvadoran economy 2 and the Salvadoran government had

begun to advocate on behalf of these formerly excluded citizens. In the mid1990s, Salvadoran officials, who saw emigrds' continued ability to send

remittances as economically necessary, joined Salvadoran activists in

campaigning for a grant of legal residency to Salvadoran nationals living in the

United States.22 The political importance of Salvadoran expatriates is

demonstrated by the fact that prior to the 1999 Salvadoran elections,

presidential candidates held community forums in Los Angeles. Similarly, in

February, 2000, a flyer publicizing a community forum in Los Angles with an

FMLN mayoral candidate for the city of San Miguel, El Salvador, announced

in Spanish: "We sustain the economy of the country, now we should sustain

it with our political participation." Indeed, Salvadoran leaders have recently

courted the U.S. Salvadoran community. 23 At a press conference in Los,

Angeles, for instance, the president of the Salvadoran Chamber of Commerce

and Business told reporters: "We want to make this community feel that being

outside of the country doesn't mean it is not part of it. That it feels it is part

of us." 12 4 In fact, in 1997, Victoria Vel.squez de Avilds, the Salvadoran

Ombudswoman for Human Rights, made the immigration and legal rights of

20. See Joseph William Singer, The Reliance Interest in Property,40 STAN. L. REV. 611-751.

I am grateful to Richard Perry for this point.

21. Cecilia Menjivar et al., Remittance Behavior Among Salvadoran and Filipino Immigrants

in Los Angeles, 32 INT'L MIGRATION REV. 97 (1998).

22. Patrick J.McDonnell, Immigrants' Plight at Issue in Costa Rica Talks, L.A. TIMES, May

8, 1997, at A32.

23. Alfredo Santana, El Salvador se hace presente en Los Angeles, LAOPINI6N, June 23, 1998,

at 2D.

24. Maria del Pilar, Ministro Salvadoreho promueve su pals, LAOPINI6N, June 26, 1998, at

9B, 2B.

2000]

DENATIONALIZATION, INCLUSION, AND EXCLUSION

591

Salvadorans living outside of El Salvador a cornerstone of her work. Emigrds'

participation in transnational community, familial, and political networks has

contributed to increasing recognition of their legal and political rights as

Salvadoran citizens.

Just as one dimension of citizenship can legitimize the conferral of another,

so too does using the term "citizenship" for participation in nonnational

groupings confer legitimacy on these entities. Bosniak rightly notes that,

"talk[ing] about citizenship in ways that locate it beyond the boundaries of the

nation-state ...[acknowledges] the increasingly transterritorial quality of

political and social life, and the need for such politics where they do not yet

exist."25 Such usages also acknowledge the transterritorial quality of

membership, and thus signal the new and not-so-new groups in which people

are situated. These groups include immigrant hometown associations that raise

funds for development in migrants' communities of origin, transnational political

movements that raise funds and garner political support for popular struggles,

and transnational family economies. Such groups sometimes perform quasigovernmental functions and thus usurp State authority. For example, some

Salvadoran immigrants have worked without authorization, transferred funds

and goods to family members through unauthorized channels, smuggled

relatives across borders, falsified documents and identities, driven without

licenses or insurance, and located family members in multiple national spaces.

Normally, only States are entitled to issue identity documents, authorize the

international movement of goods and persons, and decide who is entitled to

drive, work, or operate a business. Undocumented immigrants have

sometimes assumed the authority to make these decisions themselves, and

sometimes have even authenticated their actions (such as a decision to work

without authorization) by manufacturing their own documentation. When

individuals who have engaged in such illicit practices acquire legal status at

least in part because of these activities, then illicit practices are themselves at

least somewhat legitimized. There is thus a sense in which denationalized and

nationalized citizenship may be interdependent. The realm of "legitimate"

nationalized citizenship in some way relies on a denationalized, extrastatal,

and/or transnationa 2 6 domain of"illegitimate" citizenship (perhaps including

dual citizenship) that, in turn, can sometimes undergo "nationalization." For

instance, living outside of one's country of origin and sending remittances can

be deemed an act of patriotism, and working in a country in which one lacks

25. Bosniak, supra note 2, at 450.

26. Obviously, the transnational is not necessarily extrastatal.

592

INDIANA JOURNAL OF GLOBAL LEGAL STUDIES

[Vol. 7:585

legal status can be considered a contribution to a national economy. In each

of these examples, the denationalized is reclaimed by the national.

The complex relationships between national and denationalized citizenship

redefine naturalization as well. Naturalization is often celebrated as a moment

in which the multiple meanings of citizenship coalesce. At mass naturalization

ceremonies that I attended in Los Angeles in 1996 and 1997, judges exhorted

as many as 5,000 newly naturalized U.S. citizens to exercise their right to vote,

get involved in their communities, and take pride in being Americans.27 In

contrast to such conflations of sentiment, status, rights, and political

participation, Salvadoran immigrants who wanted to be naturalized, but were

ineligible to do so, described legalization and naturalization as strategic moves,

rather than as personal transformations. One woman told me, "I will always

be Salvadoran, regardless of where my citizenship is or what piece of paper

I have. I will never forget my little house or my little town, humble though it

is. I am not American. ' 8

Interviewees cited the freedom to travel internationally, the ability to

petition for undocumented relatives, the right to vote, and better retirement

benefits as the primary advantages ofU.S. citizenship. Some pointed out that

with either legal residency, or U.S. citizenship, they would be better connected

to families and communities abroad than they are as asylum applicants who

jeopardize their applications if they leave the United States. One Salvadoran

woman stated: "The day that I receive papers, that very day, I'm catching a

plane to go to El Salvador again. It's been eleven years since I've seen my

parents. 2 9 Interviewees also noted that more restrictive immigration policies

have sharpened distinctions between U.S. citizens and legal permanent

residents and have thereby made naturalization more important. As another

woman put it: "The way things are going, in the future, the residents will be

treated like illegals." Immigrants' legalization strategies seem to reflect their

transnational goals (e.g., to travel and immigrate family members) and their

desire to counter exclusion as much as, or even more than, their national

allegiance. Moreover, in the case of Salvadorans, such transnational and

strategic considerations have been at the heart of activists' legal campaigns

since at least the early 1980s, when large-scale immigration from El Salvador

to the United States began. During the Salvadoran civil war, activists sought

27. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service officials showed new citizens a music video

of the song, "I'm Proud to Be an American."

28. Interview with research participant, Apr. 3, 1996, Los Angeles.

29. Interview with research participant, Apr. 5, 1996, Los Angeles.

2000]

DENATIONALIZATION, INCLUSION, AND EXCLUSION

593

refugee status for Salvadoran migrants, not only to prevent deportations, but

also to force the U.S. government to acknowledge human rights abuses being

committed by the Salvadoran government. Paradoxically, Salvadoran

immigrants' ability to acquire U.S. residency derives from such transnational

political activity, including the Salvadoran government's recent advocacy on

behalf of its citizens' immigration rights.3

Thus, the moment in September, 1999, when the NACARA applicant and

I confronted State-based definitions of citizenship was preceded by a complex

(and in some ways denationalizing) history. Central Americans, such as this

applicant, left their home countries during a period of civil war and political

repression. Their Guatemalan or Salvadoran citizenship did not guarantee

political and legal rights in their homelands and proved a liability in the United

States, marking them not only as nonnationals, but also, in some cases,

deportable. Undocumented Central American immigrants who remained in the

United States nonetheless founded organizations in solidarity with political

struggles in Central America, sent remittances to family members, participated

in underground and illicit labor markets, and sought legal status in the United

States. These activities eventually resulted in limited immigration benefits,

such as NACARA, which restored suspension eligibility to certain Salvadorans

and Guatemalans. To obtain U.S. residency, eligible Salvadorans and

Guatemalans would have to define their work histories, family situations, and

community ties as indications of productivity, rootedness, and acculturation,

even though these histories, situations, and ties were created despite State

efforts to bar their presence. Moreover, immigrants' goals in seeking legal

residency and U.S. citizenship include the ability to travel internationally and

to petition for relatives. These contradictory movements between

nationalization and denationalization expose the interdependency of these

processes. By challenging the presumed superiority of State-based definitions

of citizenship and noting ways in which citizenship is denationalized, Bosniak's

article helps to make sense of the struggles in which NACARA beneficiaries

and other immigrants are engaged.

30. Transnational political work can be highly nationalistic.

For instance, Salvadoran

immigrants' support for political struggles in El Salvador were grounded in a national revolutionary

project. The Salvadoran government's advocacy on behalf of emigrds' immigration rights is both

nationalist and denationalist. Such advocacy claims Salvadoran emigrds as citizens and as part of

the Salvadoran nation in order to assist these immigrants in obtaining legal status in the United

States.

Você também pode gostar

- Common Verbs Used in Articles Fill inDocumento4 páginasCommon Verbs Used in Articles Fill inJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Object Pronouns and PossessivesDocumento3 páginasObject Pronouns and PossessivesJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Only over my dead body - DrakeDocumento2 páginasOnly over my dead body - DrakeJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Present, Continuous or Future 3Documento3 páginasPresent, Continuous or Future 3João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Common Verbs Used in ArticlesDocumento4 páginasCommon Verbs Used in ArticlesJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Do or Make CompleteDocumento12 páginasDo or Make CompleteJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- B2 Although, Albeit, Despite, Notwithstanding, Etc. Exercises 2Documento1 páginaB2 Although, Albeit, Despite, Notwithstanding, Etc. Exercises 2João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Questions About RoutineDocumento2 páginasQuestions About RoutineJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Future With Will or Be Going ToDocumento2 páginasFuture With Will or Be Going ToJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Questions About RoutineDocumento3 páginasQuestions About RoutineJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Test Intro Units 3-8 1.0Documento5 páginasTest Intro Units 3-8 1.0João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Write Questions For These Answers (DID, WAS/WERE)Documento2 páginasWrite Questions For These Answers (DID, WAS/WERE)João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- ROBBINS e STAMATOPOULOU - Reflections On Culture and Cultural RightsDocumento17 páginasROBBINS e STAMATOPOULOU - Reflections On Culture and Cultural RightsJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Physical AppearanceDocumento21 páginasPhysical AppearanceKatherineMysterieuxAinda não há avaliações

- Interchange Third Edition TEST 3A UNITS 5-6Documento2 páginasInterchange Third Edition TEST 3A UNITS 5-6João Borges100% (1)

- STARN, Orin - Writing Culture at 25 (Cultural Anthropology)Documento6 páginasSTARN, Orin - Writing Culture at 25 (Cultural Anthropology)João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Interchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsDocumento6 páginasInterchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Common Verbs Used in ArticlesDocumento4 páginasCommon Verbs Used in ArticlesJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- RILES - A New AgendaDocumento51 páginasRILES - A New AgendaJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Tempos Verbais: To Be (Ser/estar)Documento5 páginasTempos Verbais: To Be (Ser/estar)João BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- ERIKSEN - Between Universalism and RelativismDocumento13 páginasERIKSEN - Between Universalism and RelativismJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Interchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsDocumento6 páginasInterchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- CONLEY, O'BARR - Legal Anthropology Comes Home A Brief History of The EthnographiDocumento25 páginasCONLEY, O'BARR - Legal Anthropology Comes Home A Brief History of The EthnographiJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- CONLEY, O'BARR - Legal Anthropology Comes Home A Brief History of The EthnographiDocumento25 páginasCONLEY, O'BARR - Legal Anthropology Comes Home A Brief History of The EthnographiJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Interchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsDocumento6 páginasInterchange Review Book 3 - Units 9-12 With ExplanationsJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Law Notes On AntDocumento11 páginasLaw Notes On AntAmadaLibertadAinda não há avaliações

- English Placement TestDocumento4 páginasEnglish Placement TestJoão BorgesAinda não há avaliações

- Latour - Why Has Critique Run Out of SteamDocumento25 páginasLatour - Why Has Critique Run Out of Steamgabay123Ainda não há avaliações

- Bruno Latour Spinoza LecturesDocumento27 páginasBruno Latour Spinoza LecturesAlexandra Dale100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Imperialism Venn-Diagram - KeyDocumento1 páginaImperialism Venn-Diagram - KeykmsochaAinda não há avaliações

- About Canada - ImmigrationDocumento9 páginasAbout Canada - ImmigrationFernwood Publishing50% (2)

- Ipa 2Documento21 páginasIpa 2Anggara MirzaAinda não há avaliações

- Collecting Migration Data For Asian CountriesDocumento8 páginasCollecting Migration Data For Asian CountriesADBI EventsAinda não há avaliações

- 3.0 Vertical Asset Report SAP VS ACTUAL (6.27)Documento574 páginas3.0 Vertical Asset Report SAP VS ACTUAL (6.27)Ber2wheelsAinda não há avaliações

- Mollybrooke Chaturbate Newmollybrooke Camgirl Webcam Model LargeDocumento100 páginasMollybrooke Chaturbate Newmollybrooke Camgirl Webcam Model LargeiridauxeAinda não há avaliações

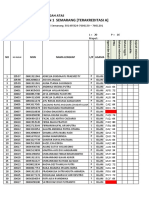

- SMA Kesatrian 1 Semarang Class ListsDocumento11 páginasSMA Kesatrian 1 Semarang Class ListsSekar NoviaRAinda não há avaliações

- Reading 2. MuslimsDocumento22 páginasReading 2. MuslimsDavidAinda não há avaliações

- Nation State EvolutionDocumento4 páginasNation State EvolutionZarmina ZaidAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 5 ExercicesDocumento189 páginasUnit 5 ExercicesVictor Lucia GomezAinda não há avaliações

- A. Introduction To PostcolonialismDocumento4 páginasA. Introduction To PostcolonialismRafiii GoodguywannabeAinda não há avaliações

- Immigration EssayDocumento3 páginasImmigration EssaystealphAinda não há avaliações

- Models of Spatial RelationshipsDocumento36 páginasModels of Spatial RelationshipsAnthony HaAinda não há avaliações

- Bale - Sport, Space and Body CultureDocumento10 páginasBale - Sport, Space and Body CultureFabio Daniel Rios100% (1)

- 2017 Annual ReportDocumento6 páginas2017 Annual ReportImmigrant Legal Resource CenterAinda não há avaliações

- UNIT 6 (MyELT)Documento12 páginasUNIT 6 (MyELT)Edson Vasquez Arce100% (2)

- Kak Bahasa Inggeris THN 1 - 6Documento4 páginasKak Bahasa Inggeris THN 1 - 6Sea HunterAinda não há avaliações

- Postcolonial Imagination and Postcolonial TheoryDocumento11 páginasPostcolonial Imagination and Postcolonial TheoryDUBIOUSBIRDAinda não há avaliações

- Perceptions Dergi 2012 Summer-OpDocumento172 páginasPerceptions Dergi 2012 Summer-OpRoxana TurotiAinda não há avaliações

- Akehurst RecognitionDocumento11 páginasAkehurst RecognitionNori LolaAinda não há avaliações

- Dinas Pendidikan Sma Negeri 1 Tambusai: Pemerintah Provinsi RiauDocumento3 páginasDinas Pendidikan Sma Negeri 1 Tambusai: Pemerintah Provinsi RiauEva SimanungkalitAinda não há avaliações

- Study On Colonialism of English and Spanish Language - ArticleDocumento5 páginasStudy On Colonialism of English and Spanish Language - ArticleJohn JeiverAinda não há avaliações

- FWRISA Licensed Immigration Consultants December 2019 PDFDocumento42 páginasFWRISA Licensed Immigration Consultants December 2019 PDFRene FresnedaAinda não há avaliações

- Question PDFDocumento150 páginasQuestion PDFLiev S. VigotskiAinda não há avaliações

- National Language Policy in the PhilippinesDocumento4 páginasNational Language Policy in the PhilippinesHannah Jerica CerenoAinda não há avaliações

- Language Endangerment HotspotsDocumento1 páginaLanguage Endangerment HotspotsMegan KennedyAinda não há avaliações

- Immigration Act 1924Documento4 páginasImmigration Act 1924niklaus2012Ainda não há avaliações

- Graeme Hugo, "Migration in The Asia-Pacific Region"Documento62 páginasGraeme Hugo, "Migration in The Asia-Pacific Region"Mila JesusAinda não há avaliações

- APWH - Unit 5 Sections 6.1-6.3 "Rationales For Imperialism," "State Expansion," "Indigenous Responses To State Expansion"Documento7 páginasAPWH - Unit 5 Sections 6.1-6.3 "Rationales For Imperialism," "State Expansion," "Indigenous Responses To State Expansion"Cannon CannonAinda não há avaliações

- We3 01 04 02Documento1 páginaWe3 01 04 02Bill SuarezAinda não há avaliações