Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Social Security in Malaysia

Enviado por

GraceYeeDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Social Security in Malaysia

Enviado por

GraceYeeDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

Social Security in Malaysia

!

Social security traditionally means a social insurance program providing social protection,

or protection against socially recognized conditions, including poverty, old age, disability,

unemployment and others. It also hovers around the subject of social insurance, where people

receive benefits or services in recognition of contributions to an insurance scheme. Providing

services for medical care, aspects of social work and even industrial relations may be included as

part of social security services. Contemporary social security schemes in Malaysia derived its origin

from provisions introduced during the colonial era. The earliest social security provisions were a

workmens compensation scheme, established in 1929, and an employers liability, sickness, and

maternity scheme for plantation workers, introduced in 1933. Present day social protection in

Malaysia is covered in two sectors - the formal sector and informal sector.

!

The formal sector in Malaysia comprises organized and registered economic activities

that operate within the legal institutional framework, and generally generate regular wages and

incomes. Employers are required to comply with legal social protection institutions, in particular

old-age savings for all employees and accident/death insurance for low-income workers. Workers

have the option of joining trade unions, although subject to severe restrictions as mentioned above.

Working conditions and hours also have to fall within certain limits, and workplaces abide by safety

regulations.

!

Only employees in the government service are entitled to receive pensions upon retirement

while all other employees are required to contribute to an old-age retirement scheme known as the

Employees Provident Fund (EPF) or in Malay, Kumpulan Wang Simpanan Pekerja (KWSP). The

Government Pension Ordinance of 1951 introduced a non-contributory pension scheme for civil

servants, which was amended by the Pensions Act of 1980. This scheme provides income protection

for all employees in the public sector. Benefits include those relevant to employment injury,

disability, superannuation or gratuity payment upon retirement and dependents pension in the event

of death while in service and death after retirement. The generous provisions of the civil service

pension scheme are funded by the government through tax revenues. For the majority of employees

outside the civil service, there is the statutory provident fund that provides retirement benefits under

!1

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

the Employee Provident Fund Act, 1951. The EPF scheme consists of individual and entirely

separate accounts for each worker. Contributions are paid by workers and employers. The employer

pays a contribution rate of 12% of the workers monthly rate, while the employee contributes 11%,

and these accumulate to earn dividends until the amount is paid out on the occurrence of the

prescribed contingencies of retirement or death, provided that retirement is not before the statutory

age, initially 55 but revised to 60 under the Minimum Retirement Age Act 2012. Each workers EPF

account is divided into three components. Account 1 comprises 60% of total savings and can be

withdrawn only upon reaching the age of 55 years. The government announced that there are no

immediate plans to raise the EPF withdrawal age to 60. Account 2 comprises 30% of total savings

and withdrawals are allowed for the purpose of purchasing a house, a computer and education. The

last 10% of the savings are deposited into Account 3, and withdrawals are allowed for medical

expenses.

There is also the Employers Liability Scheme (ELS) covers mainly two types of benefits.

Firstly, employment injury compensation and secondly, sickness and maternity benefits. Paid sick

leave entitlement depends on the employees length of service. It ranges from 14 days for those

employed for less than two years, and 18 days for those employed between two to five years, to 22

days if the employee has served the employer for more than five years. All female employees

covered by this scheme are entitled to 60 days maternity leave, subject to a maximum of five

surviving births, plus a maternity benefit which is an amount equivalent to her wages at the time of

confinement. This sum should be paid even if the employee dies (from any cause) during the

maternity leave.

!

The Social Security Organization (SOCSO), or its Malay equivalent Pertubuhan

Keselamatan Sosial (PERKESO), covers worker who earn less than RM2,000 a month and is

financed by contributions by the workers and employers. There are two types of benefits that are

administered by SOCSO, namely, the Employment Injury Insurance scheme and the Invalidity

Pension scheme. Under the former, the contribution rate is 1.25% of the employees monthly

earnings, and in the latter scheme it is 1%; the contributions are shared equally between the

employer and the employee. Under the first scheme, the benefits provided include medical benefit,

temporary disability benefit, permanent disability benefit, dependents benefit, death benefit, and

rehabilitation benefit. On the other hand, the Invalidity Pensions scheme provides coverage against

invalidity or death due to any cause. The benefits provided are related to temporary or permanent

!2

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

disability and rehabilitation, funeral grant, survivors pension and educational benefits. Benefits are

paid out in the form of periodical payments, calculated on an earnings-related basis.

!

Under the Workers Compensation Scheme, the injured or deceased workman is

compensated by his employer, who is required to insure his company against such liabilities. Unlike

SOCSO, this scheme operates as a law governing the terms and amounts of compensation in the

case of death or accident. It does not handle the funds itself; the employer is fully responsible for

the social insurance through private companies. This scheme has also been particularly important to

foreign workers in Malaysia.

!

A large section of the population, in particular the self-employed, petty commodity traders,

and those employed in the informal sector, are excluded from any formal social security measures.

In the context of social protection, it is quite likely that these self-employed do not have access to

formal protection, or do not involve themselves in such programmes. Registering as EPF

contributors, for instance, requires declaring incomes that they may not wish to disclose. More often

than not, they are exposed to potential risks from natural, social and economic hazards, are least

protected against these hazards compared to employees in the formal sector. They face economic

insecurity due to unstable income; while at the same time they lack the skills and capital needed to

diversify into other forms of income generating activities or seek better opportunities elsewhere.

!

Malaysia is classified as a medium income country with PPP per capita GDP of USD 312.44

billion in 2014 (Trading Economics, 2015) and its latest GDP growth rate is 5.6%. The current

population growth rate is 1.6% and seems likely to decrease in the coming years. Although

Malaysia is not currently an aged society, the proportion of the older population (defined as 60

years or older) is forecast to reach 9.9% by 2020. The older population aged 60 years and over will

likely outnumber the younger population aged 15 years old and below by 2045. It looks like the

current social security structure is still sustainable in the near future, but this could also be seen as

added pressure on the government to provide jobs for the large number of young adults entering the

labour market and at the same time, providing some form of protection for the elderly population.

Globalization has also made safety nets even more essential for three reasons; cushioning the

burden of restructuring, increasing legitimacy of reforms; and enabling risk taking by individuals

and firms by providing a floor level income in the event that risk taking ventures fail to materialise.

!3

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

More importantly, an improved coverage will foster social cohesion and sustainable economic

development.

!

The Malaysian social security system still suffer some shortcomings. All the schemes

mentioned only cover contributions until the age of 55. After that, the employee has to use his

pension or any other funds. Lump sump withdrawals also leave beneficiaries at danger of using up

the money in a short amount of time. In addition, there is no such thing as unemployment insurance;

the only payments the unemployed receive are the payments of termination as stated in the Labour

Law. Lack of child and family social schemes are just as important an issue as the exclusion of selfemployers from compulsory insurance. Members of low-income groups who are not covered by

social security are at a disadvantage, not only by being excluded in coverage but also as a result of

their contribution to the general taxation.

That said, it is worth mentioning here that there is no perfect social security system in the

world. Each country has its own strengths and weaknesses. Malaysia should look to other countries

and find out how they can further improve on what have been developed. The roles of all the

agencies and ministries in the social security system also need to be relook with better integration to

provide well coordinated care that covers the entire population.

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

!4

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

Appendix

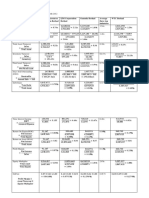

Age structure

Percentage

0-14

28.8

15-24

16.9

25-54

41.2

55-64

7.6

65 and over

5.5

!5

Current Japanese Economy B

Grace Yee 1147340056

References

1. Singh S. (2010). Employers must make EPF, Socso contributions to part-timers. The Star Online.

Retrieved 13 January 2015, from http://www.thestar.com.my/story/?sec=nation&file=

%2F2010%2F8%2F18%2Fnation%2F20100818160440

!

2. N.A. Social security and welfare benefits in Malaysia. Angloinfo. Retrieved 13 January 2015,

from http://malaysia.angloinfo.com/money/social-security/

!

3. Holzmann R. (2014). Old age financial protection in Malaysia. Retrieved 13 January 2015, from

http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/

2014/11/25/000442464_20141125150658/Rendered/PDF

927250NWP014250Box385377B00PUBLIC0.pdf

!6

Você também pode gostar

- National Bank Act A/k/a Currency Act, Public Law 38, Volume 13 Stat 99-118Documento21 páginasNational Bank Act A/k/a Currency Act, Public Law 38, Volume 13 Stat 99-118glaxayiii100% (1)

- (Methods in Molecular Biology 1496) William J. Brown - The Golgi Complex - Methods and Protocols-Humana Press (2016)Documento233 páginas(Methods in Molecular Biology 1496) William J. Brown - The Golgi Complex - Methods and Protocols-Humana Press (2016)monomonkisidaAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security: The New Rules, Essentials & Maximizing Your Social Security, Retirement, Medicare, Pensions & Benefits Explained In One PlaceNo EverandSocial Security: The New Rules, Essentials & Maximizing Your Social Security, Retirement, Medicare, Pensions & Benefits Explained In One PlaceAinda não há avaliações

- A Beautiful Mind - Psychology AnalysisDocumento15 páginasA Beautiful Mind - Psychology AnalysisFitto Priestaza91% (34)

- Social Security SchemesDocumento26 páginasSocial Security SchemesharishAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar On DirectingDocumento22 páginasSeminar On DirectingChinchu MohanAinda não há avaliações

- Hypnosis ScriptDocumento3 páginasHypnosis ScriptLuca BaroniAinda não há avaliações

- Extinct Endangered Species PDFDocumento2 páginasExtinct Endangered Species PDFTheresaAinda não há avaliações

- SOCSODocumento22 páginasSOCSOpkalyraAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Analysis of The Unemployment Schemes in IndiaDocumento35 páginasCritical Analysis of The Unemployment Schemes in IndiaArtika AshdhirAinda não há avaliações

- Ocial Security IN Alaysia: Present by Teh Pei ShanDocumento19 páginasOcial Security IN Alaysia: Present by Teh Pei ShanPei ShanAinda não há avaliações

- Pension Reform in India - A Social Security Need (D. Swarup, Chairman, PFRDA)Documento16 páginasPension Reform in India - A Social Security Need (D. Swarup, Chairman, PFRDA)Andre NoortAinda não há avaliações

- 13 Okt - General 2 - The Sun DailyDocumento4 páginas13 Okt - General 2 - The Sun DailyNor Iskandar Md NorAinda não há avaliações

- 31 Okt - General 3 - Daily Express PDFDocumento3 páginas31 Okt - General 3 - Daily Express PDFNor Iskandar Md NorAinda não há avaliações

- NLM ReportDocumento58 páginasNLM ReportBon QuiapoAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment On LL IDocumento8 páginasAssignment On LL Itanmaya_purohitAinda não há avaliações

- Labour Law II - 1582Documento22 páginasLabour Law II - 1582Maneesh ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Module 7-SOCIAL-SECURITY-INSURANCEDocumento22 páginasModule 7-SOCIAL-SECURITY-INSURANCEArmand RoblesAinda não há avaliações

- Social Insurance ProgramsDocumento12 páginasSocial Insurance Programsermirakastrati2004Ainda não há avaliações

- Policy Paper On SSSDocumento21 páginasPolicy Paper On SSSom_lawAinda não há avaliações

- Social Securities and RewardsDocumento18 páginasSocial Securities and RewardskragniveshAinda não há avaliações

- Student Guide 14 - Types of Compensation - II-1695645202631Documento9 páginasStudent Guide 14 - Types of Compensation - II-1695645202631Navin KumarAinda não há avaliações

- R.A. No. 8282Documento8 páginasR.A. No. 8282Nenita OcarizaAinda não há avaliações

- Labour Law IndDocumento7 páginasLabour Law IndVipin KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Social Welfare Legislation LectureDocumento16 páginasSocial Welfare Legislation LectureAllyza RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security DefinedDocumento2 páginasSocial Security DefinedMarlou AbejuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Alegria ReportDocumento26 páginasAlegria ReportChikahantayo TVAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security Measures Across The Countries : Presented byDocumento16 páginasSocial Security Measures Across The Countries : Presented byYuvika SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- UI Policy BriefDocumento6 páginasUI Policy BriefNimajneb SenipmuladAinda não há avaliações

- Chapters 11 13Documento68 páginasChapters 11 13Shanley Duenn UdtohanAinda não há avaliações

- Socso 1Documento3 páginasSocso 1默默Ainda não há avaliações

- Worker's Compensation ActDocumento46 páginasWorker's Compensation ActMehna NajeemAinda não há avaliações

- Keywords:: Pension Pension Reform Workers Well-Being Error Correction ModelDocumento14 páginasKeywords:: Pension Pension Reform Workers Well-Being Error Correction ModelrevolutionguyAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Pension System: Problems and PrognosisDocumento38 páginasIndian Pension System: Problems and PrognosisDennykumarAinda não há avaliações

- Eloisa S. Gavilan BSBA-HR2nd YrDocumento2 páginasEloisa S. Gavilan BSBA-HR2nd YrGoldengate CollegesAinda não há avaliações

- Broad-Based Growth VitalDocumento3 páginasBroad-Based Growth VitalTithi jainAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security in India - 2Documento24 páginasSocial Security in India - 2Amitav TalukdarAinda não há avaliações

- GoswamiDocumento38 páginasGoswamiMahendra SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Project On Pension Funds Submitted To: Ma Am Saadia Noureen: Submitted By: Shafaq Munir Iqra Mazhar Aamna ImtiazDocumento16 páginasProject On Pension Funds Submitted To: Ma Am Saadia Noureen: Submitted By: Shafaq Munir Iqra Mazhar Aamna Imtiazaaminahsheikh92Ainda não há avaliações

- SSS Ira Version EditedDocumento52 páginasSSS Ira Version EditedOscar E ValeroAinda não há avaliações

- Non Bank Financial InstitutionsDocumento11 páginasNon Bank Financial InstitutionsArgilyn MagaAinda não há avaliações

- SSSDocumento91 páginasSSSLou Thez Geniza100% (1)

- Social Security Dynamics in UgandaDocumento7 páginasSocial Security Dynamics in Ugandaawech francisAinda não há avaliações

- Eco 226 Lecture 5: Informal and Formal (Modern) Sector: Informal Sector/economyDocumento8 páginasEco 226 Lecture 5: Informal and Formal (Modern) Sector: Informal Sector/economyayobola charlesAinda não há avaliações

- Employee Welfare and Benefit SchemesDocumento31 páginasEmployee Welfare and Benefit SchemesSandhya R NairAinda não há avaliações

- 1598 - Labour Law IIDocumento14 páginas1598 - Labour Law IINeha SAinda não há avaliações

- Pension InsurnaceDocumento85 páginasPension InsurnaceBhavika TheraniAinda não há avaliações

- Social Welfare LegislationDocumento12 páginasSocial Welfare LegislationMarianita CenizaAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security: These Contingencies Include - Employment, Injury, Sickness, Invalidism, Occupational DiseaseDocumento7 páginasSocial Security: These Contingencies Include - Employment, Injury, Sickness, Invalidism, Occupational DiseaseS M Arefin ShahriarAinda não há avaliações

- CIA 1 Compensation ManagementDocumento5 páginasCIA 1 Compensation ManagementKURIAN S ABRAHAM 2137908Ainda não há avaliações

- Indonesia: Providing Health Insurance For The Poor: Series: Social Security Extension Initatives in South East AsiaDocumento7 páginasIndonesia: Providing Health Insurance For The Poor: Series: Social Security Extension Initatives in South East Asiadamai02Ainda não há avaliações

- Cliff Notes - Social SecurityDocumento3 páginasCliff Notes - Social SecurityJohnathan JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- MANDATORY EMPLOYEE BENEFITS (Revised)Documento3 páginasMANDATORY EMPLOYEE BENEFITS (Revised)xenoviaAinda não há avaliações

- Labour Law CREDocumento8 páginasLabour Law CREBirmati YadavAinda não há avaliações

- Code On Social Security: An Exercise of Deception and FraudDocumento22 páginasCode On Social Security: An Exercise of Deception and FraudyehudimehtaAinda não há avaliações

- Social Security Concept of Social SecurityDocumento4 páginasSocial Security Concept of Social SecurityvengataraajaneAinda não há avaliações

- Uum College of Law, Government and International Studies: GroupDocumento11 páginasUum College of Law, Government and International Studies: Groupjadyn nicholasAinda não há avaliações

- Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund: Employees' Compensation Scheme (Ecs)Documento4 páginasNigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund: Employees' Compensation Scheme (Ecs)Chris OpubaAinda não há avaliações

- Industrial Relations, Ir - Social Security....Documento7 páginasIndustrial Relations, Ir - Social Security....rashmi_shantikumarAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation Ap Apr 11Documento8 páginasPresentation Ap Apr 11Ace ShanAinda não há avaliações

- China's Social Security System - China Labour BulletinDocumento13 páginasChina's Social Security System - China Labour BulletinAvinash KhilnaniAinda não há avaliações

- Employees' Social Security Act 1969 (SOCSO)Documento8 páginasEmployees' Social Security Act 1969 (SOCSO)JESSIE THOOAinda não há avaliações

- Pension Fund and Provident FundDocumento17 páginasPension Fund and Provident FunddarshankumartoliaAinda não há avaliações

- 08 Rajasekhar Social Security in IndiaDocumento24 páginas08 Rajasekhar Social Security in IndiaLokesh ParasharAinda não há avaliações

- Pensions in Italy: The guide to pensions in Italy, with the rules for accessing ordinary and early retirement in the public and private systemNo EverandPensions in Italy: The guide to pensions in Italy, with the rules for accessing ordinary and early retirement in the public and private systemAinda não há avaliações

- Company / Ratio Malaysia Resources Corporation Berhad IJM Corporation Berhad Gamuda Berhad Average Three Top Industries WTC BerhadDocumento3 páginasCompany / Ratio Malaysia Resources Corporation Berhad IJM Corporation Berhad Gamuda Berhad Average Three Top Industries WTC BerhadGraceYeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Du Pont System of The Analysis of Return Ratios: Applied To Sears, Roebuck & CoDocumento5 páginasThe Du Pont System of The Analysis of Return Ratios: Applied To Sears, Roebuck & CoGraceYeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Du Pont System of The Analysis of Return Ratios: Applied To Sears, Roebuck & CoDocumento5 páginasThe Du Pont System of The Analysis of Return Ratios: Applied To Sears, Roebuck & CoGraceYeeAinda não há avaliações

- China vs. IndiaDocumento2 páginasChina vs. IndiaGraceYeeAinda não há avaliações

- L 1 One On A Page PDFDocumento128 páginasL 1 One On A Page PDFNana Kwame Osei AsareAinda não há avaliações

- DMemo For Project RBBDocumento28 páginasDMemo For Project RBBRiza Guste50% (8)

- Roman Roads in Southeast Wales Year 3Documento81 páginasRoman Roads in Southeast Wales Year 3The Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust LtdAinda não há avaliações

- Genomics - FAODocumento184 páginasGenomics - FAODennis AdjeiAinda não há avaliações

- SULTANS OF SWING - Dire Straits (Impresión)Documento1 páginaSULTANS OF SWING - Dire Straits (Impresión)fabio.mattos.tkd100% (1)

- Order of Magnitude-2017Documento6 páginasOrder of Magnitude-2017anon_865386332Ainda não há avaliações

- Coordination Compounds 1Documento30 páginasCoordination Compounds 1elamathiAinda não há avaliações

- Rebecca Young Vs CADocumento3 páginasRebecca Young Vs CAJay RibsAinda não há avaliações

- Entrepreneurial Skills and Intention of Grade 12 Senior High School Students in Public Schools in Candelaria Quezon A Comprehensive Guide in Entrepreneurial ReadinessDocumento140 páginasEntrepreneurial Skills and Intention of Grade 12 Senior High School Students in Public Schools in Candelaria Quezon A Comprehensive Guide in Entrepreneurial ReadinessAngelica Plata100% (1)

- Research Report On Energy Sector in GujaratDocumento48 páginasResearch Report On Energy Sector in Gujaratratilal12Ainda não há avaliações

- Gee 103 L3 Ay 22 23 PDFDocumento34 páginasGee 103 L3 Ay 22 23 PDFlhyka nogalesAinda não há avaliações

- Wwe SVR 2006 07 08 09 10 11 IdsDocumento10 páginasWwe SVR 2006 07 08 09 10 11 IdsAXELL ENRIQUE CLAUDIO MENDIETAAinda não há avaliações

- De Luyen Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam Hoc 2019Documento106 páginasDe Luyen Thi Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam Hoc 2019Mai PhanAinda não há avaliações

- Economies of Scale in European Manufacturing Revisited: July 2001Documento31 páginasEconomies of Scale in European Manufacturing Revisited: July 2001vladut_stan_5Ainda não há avaliações

- TEsis Doctoral en SuecoDocumento312 páginasTEsis Doctoral en SuecoPruebaAinda não há avaliações

- Sarcini: Caiet de PracticaDocumento3 páginasSarcini: Caiet de PracticaGeorgian CristinaAinda não há avaliações

- SEW Products OverviewDocumento24 páginasSEW Products OverviewSerdar Aksoy100% (1)

- PCI Bank V CA, G.R. No. 121413, January 29, 2001Documento10 páginasPCI Bank V CA, G.R. No. 121413, January 29, 2001ademarAinda não há avaliações

- K3VG Spare Parts ListDocumento1 páginaK3VG Spare Parts ListMohammed AlryaniAinda não há avaliações

- Speaking Test FeedbackDocumento12 páginasSpeaking Test FeedbackKhong TrangAinda não há avaliações

- Recent Cases On Minority RightsDocumento10 páginasRecent Cases On Minority RightsHarsh DixitAinda não há avaliações

- Ollie Nathan Harris v. United States, 402 F.2d 464, 10th Cir. (1968)Documento2 páginasOllie Nathan Harris v. United States, 402 F.2d 464, 10th Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Monastery in Buddhist ArchitectureDocumento8 páginasMonastery in Buddhist ArchitectureabdulAinda não há avaliações

- Q3 Lesson 5 MolalityDocumento16 páginasQ3 Lesson 5 MolalityAly SaAinda não há avaliações