Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Denying Rights of Self-Represented Litigants - Benchguide for Judicial Officers Judicial Council of California - Handling Cases Involving Self-Represented Litigants - Supreme Court of California Tani Cantil-Sakauye - Commission on Judicial Performance Victoria B. Henley Director CJP

Enviado por

California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

168 visualizações3 páginasJudges Benchguide: Handling Cases Involving Self-Represented Litigants.

Denying Rights of Self-Represented Litigants:

"The Supreme Court and the Commission on Judicial Performance have, on numerous occasions, disciplined judges or removed them from office for their denial of the rights of unrepresented litigants appearing before them."

Direitos autorais

© Public Domain

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoJudges Benchguide: Handling Cases Involving Self-Represented Litigants.

Denying Rights of Self-Represented Litigants:

"The Supreme Court and the Commission on Judicial Performance have, on numerous occasions, disciplined judges or removed them from office for their denial of the rights of unrepresented litigants appearing before them."

Direitos autorais:

Public Domain

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

168 visualizações3 páginasDenying Rights of Self-Represented Litigants - Benchguide for Judicial Officers Judicial Council of California - Handling Cases Involving Self-Represented Litigants - Supreme Court of California Tani Cantil-Sakauye - Commission on Judicial Performance Victoria B. Henley Director CJP

Judges Benchguide: Handling Cases Involving Self-Represented Litigants.

Denying Rights of Self-Represented Litigants:

"The Supreme Court and the Commission on Judicial Performance have, on numerous occasions, disciplined judges or removed them from office for their denial of the rights of unrepresented litigants appearing before them."

Direitos autorais:

Public Domain

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 3

Handling Cases

Involving

Self-Represented

Litigants

A BENCHGUIDE FOR JUDICIAL

OFFICERS

JANUARY 2007

A Benchguide for Judicial Officers

January 2007

stated, By undertaking a collateral investigation [the judge] abdicated

his responsibility for deciding the parties dispute on pleadings and

evidence properly brought before him. 29 Cal.3d 615, at 632.

Denying rights of self-represented litigants

The Supreme Court and the Commission on Judicial Performance have,

on numerous occasions, disciplined judges or removed them from

office for their denial of the rights of unrepresented litigants appearing

before them.

In Kennick v. Commission on Judicial Performance (1990) 50 Cal.3d

297, 787 P.2d 591 [267 Cal.Rptr. 293], the Supreme Court removed a

judge from office for, among other things, rudeness to pro per litigants

in criminal cases.

In McCartney v. Commission on Judicial Qualifications (1974) 12 Cal.3d

512, 526 P.2d 268 [116 Cal.Rptr. 260], the court censured a judge for,

among other things, bullying and badgering pro per criminal

defendants.

In Inquiry Concerning Judge Fred L. Heene, Jr., No. 153 (Commission

on Judicial Performance 1999), the commission censured a judge for,

among other things, not allowing an unrepresented defendant in a

traffic case to cross-examine the police officer and failing, in several

cases, to respect the rights of unrepresented litigants.

In Inquiry Concerning a Judge, No. 133 (Commission on Judicial

Performance 1996), the commission censured a judge for, among

other things, pressuring self-represented litigants to plead guilty,

penalizing a self-represented litigant who exercised his right to trial,

and conducting a demeaning examination of an unrepresented litigant.

A trial judge may not deny the parties their procedural due process

rights by preempting their ability to present their case. In Inquiry

Concerning Judge Howard R. Boardman, No. 145 (Commission on

Judicial Performance 1999), the commission concluded that Judge

Boardman committed willful misconduct by depriving the parties of

their procedural rights in King v. Wood. The case, filed by a selfrepresented litigant, involved a quiet title action concerning a home.

The counsel for the opposing party was trying his first case. Judge

Boardman called the case for trial and, telling the parties that he was

proceeding off the record and without swearing the parties, asked

them to tell him what the case was about. The self-represented litigant

3-16

spoke, followed by the lawyers opening statement and his clients

statement. The judge alternated asking the parties questions. He

reviewed documents presented to him. After asking if either party had

anything else to add, he announced that he was taking the case under

submission and asked the attorney to prepare a statement of decision

and judgment, which the judge later signed. The commission

concluded that Judge Boardman, on his own initiative and without

notice to or consent by the parties, followed an alternative order in a

misplaced effort to conserve judicial resources. It noted that the

parties were denied their rights to present and cross-examine

witnesses and to present evidence.

Limitations on a trial judges accommodation of a self-represented

litigant

What accommodation might be inappropriate for a trial judge to make?

The limitation articulated in federal case law is whether the

accommodation would cause prejudice to the opposing side.

However, it appears that prejudice is confined strictly to instances in

which the judges actions led to a decision contrary to that dictated by

the facts and the law of the case. For instance, a judges helping a

party to introduce evidence essential for recovery would not be

prejudicial to the other side, since the judges action resulted in

evidence showing that the other side was not entitled to prevail.

An informal ethics opinion by the California Judges Association (20012002 Informal Response #62 (Gutierrez) Nov. 30, 2001 addresses the

issue of whether, in a small claims court proceeding, it is proper for a

judge to suggest that the plaintiff may want to ask for medical costs or

other damages in addition to the requested compensation for vehicle

damages. Section 1.3 of the Judges Benchbook describes the judges

role during small claims proceedings. Specifically the benchbook

states: the judge cannot sit back and be a passive arbiter. . . . The

judge should see that, when appropriate, issues such as the statute of

frauds and limitations or other special statutory requirements are

raised even though the parties fail to do so. This is particularly true of

statutes designed to protect consumers, because litigants are often not

aware of them. Additionally, the benchbook and benchguide [34,

Small Claims Court] note that the judge has the discretion to

investigate the facts personally. The opinion concludes that

notwithstanding this active role, making a suggestion regarding

additional damages would be improper because it goes beyond

statutes or issues of which litigants are often unaware. Instead, the

suggestion is partisan, not impartial, and amounts to advocacy.

3-17

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Respondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryDocumento135 páginasRespondent's Statement of Issues in Re Marriage of Lugaresi: Alleged Human Trafficking Case Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James ToweryCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeDocumento11 páginasAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Disqualification of Judge John Ouderkirk - JAMS Private JudgeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Prosecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDocumento1 páginaProsecutor Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney of Santa Clara County Controversy - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Terry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketDocumento64 páginasTerry Houghton and Valerie Houghton Felony Criminal Complaint and DocketCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Prosecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyDocumento2 páginasProsecutorial Misconduct: Jeff Rosen District Attorney Subordinate Jay Boyarsky - Santa Clara CountyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- "GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsDocumento4 páginas"GENERAL ORDER RE: EXPRESSIVE ACTIVITY" Restricting Free Speech Outside Santa Clara County Courthouses Issued by Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas on February 22, 2017 - Civil Rights - Free Speech - Freedom of Association - Constitutional RightsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- DA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyDocumento4 páginasDA Jeff Rosen Prosecutor Misconduct: Assistant DA Boyarsky Rebuked by Court - Santa Clara County - Silicon ValleyCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Angelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkDocumento44 páginasAngelina Jolie V Brad Pitt: Order On Misconduct by Judge John OuderkirkCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- 2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtDocumento24 páginas2016 US DOJ MOU With St. Louis County Family CourtCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteDocumento55 páginasFederal Class Action Lawsuit Against California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye For Illegal Use of Vexatious Litigant StatuteCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Silicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsDocumento8 páginasSilicon Valley District Attorney Threatens Whistleblower Complaint Against Public Defender Over Protest Blog PostsCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- District Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeDocumento1 páginaDistrict Attorney Jeff Rosen Misconduct: Santa Clara County District Attorney's Office - Silicon Valley Criminal JusticeCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Motion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Documento15 páginasMotion to Dismiss for Loss or Destruction of Evidence (Trombetta) Filed July 5, 2018 by Defendant Susan Bassi: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (2)

- E.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCADocumento55 páginasE.T. v. Ronald George Class Action Complaint USDC EDCACalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Judge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201Documento38 páginasJudge Bruce Mills Misconduct Prosecution by the Commission on Judicial Performance: Report of the Special Masters: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law - Contra Costa County Superior Court Inquiry Concerning Judge Bruce Clayton Mills No. 201California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Opposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Documento6 páginasOpposition to Murgia Motion to Compel Discovery Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasDocumento13 páginasFederal Criminal Indictment - US v. Judge Joseph Boeckmann - Wire Fraud, Honest Services Fraud, Travel Act, Witness Tampering - US District Court Eastern District of ArkansasCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Opposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -Documento4 páginasOpposition to Motion to Dismiss (Trumbetta) Filed August 9, 2018 by Plaintiff People of the State of California:: People v. Bassi - Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen, Deputy District Attorney Alison Filo - Defense Attorney Dmitry Stadlin - Judge John Garibaldi - Santa Clara County Superior Court Presiding Judge Patricia Lucas - Silicon Valley California -California Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Placing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportDocumento153 páginasPlacing Children at Risk: Questionable Psychologists and Therapists in The Sacramento Family Court and Surrounding Counties - Karen Winner ReportCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas50% (2)

- Judge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliDocumento10 páginasJudge Jack Komar: A Protocol For Change 2000 - Santa Clara County Superior Court Controversy - Judge Mary Ann GrilliCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Profile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictDocumento3 páginasProfile of Justice Coleman A. Blease, California Appellate Courts - Third DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Garrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloDocumento2 páginasGarrett Dailey Attorney Misconduct - Perjury Allegations in Marriage of Brooks - Attorney Bradford Baugh, Joseph RussielloCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantDocumento4 páginasIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: AppellantCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictDocumento13 páginasIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Judicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaDocumento3 páginasJudicial Profile: Coleman Blease, 3rd District Court of Appeal CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Qeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictDocumento2 páginasQeourt of Peal of TBT S Tatt of Qealifomia: Third Appellate DistrictCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefDocumento19 páginasIn The Court of Appeal of The State of California: Appellant'S Reply BriefCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story Ideas100% (1)

- Appellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDocumento50 páginasAppellant'S Opening Brief: in The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- In The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaDocumento9 páginasIn The Court of Appeal of The State of CaliforniaCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

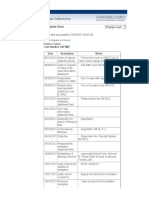

- 3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMDocumento9 páginas3rd Appellate District Change Court: Court Data Last Updated: 03/26/2017 08:40 AMCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Role of Christian Education in Socia Group 6Documento6 páginasThe Role of Christian Education in Socia Group 6Ṭhanuama BiateAinda não há avaliações

- Leading a Community Through Integrity and CourageDocumento2 páginasLeading a Community Through Integrity and CourageGretchen VenturaAinda não há avaliações

- Extinction - WikipediaDocumento14 páginasExtinction - Wikipediaskline3Ainda não há avaliações

- Testing Your Understanding: The Dash, Slash, Ellipses & BracketsDocumento2 páginasTesting Your Understanding: The Dash, Slash, Ellipses & BracketsBatsaikhan DashdondogAinda não há avaliações

- The Islam Question - Should I Become A Muslim?Documento189 páginasThe Islam Question - Should I Become A Muslim?Aorounga100% (1)

- Perkin Elmer Singapore Distribution CaseDocumento3 páginasPerkin Elmer Singapore Distribution CaseJackie Canlas100% (1)

- Web Search - One People's Public Trust 1776 UCCDocumento28 páginasWeb Search - One People's Public Trust 1776 UCCVincent J. CataldiAinda não há avaliações

- Formula Sheet For Astronomy 1 - Paper 1 and Stars & PlanetsDocumento2 páginasFormula Sheet For Astronomy 1 - Paper 1 and Stars & PlanetsprashinAinda não há avaliações

- Paul Daugerdas IndictmentDocumento79 páginasPaul Daugerdas IndictmentBrian Willingham100% (2)

- June 2016 - QuestionsDocumento8 páginasJune 2016 - Questionsnasir_m68Ainda não há avaliações

- Connectors/Conjunctions: Intermediate English GrammarDocumento9 páginasConnectors/Conjunctions: Intermediate English GrammarExe Nif EnsteinAinda não há avaliações

- Elementary Hebrew Gram 00 GreeDocumento216 páginasElementary Hebrew Gram 00 GreeRobert CampoAinda não há avaliações

- People vs. Abad SantosDocumento2 páginasPeople vs. Abad SantosTrixie PeraltaAinda não há avaliações

- Di OutlineDocumento81 páginasDi OutlineRobert E. BrannAinda não há avaliações

- Software Security Engineering: A Guide for Project ManagersDocumento6 páginasSoftware Security Engineering: A Guide for Project ManagersVikram AwotarAinda não há avaliações

- Adjustment DisordersDocumento2 páginasAdjustment DisordersIsabel CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- Jolly Phonics Teaching Reading and WritingDocumento6 páginasJolly Phonics Teaching Reading and Writingmarcela33j5086100% (1)

- ArenavirusDocumento29 páginasArenavirusRamirez GiovarAinda não há avaliações

- 4 Reasons To Walk With GodDocumento2 páginas4 Reasons To Walk With GodNoel Kerr CanedaAinda não há avaliações

- Universitas Alumni Psikotest LolosDocumento11 páginasUniversitas Alumni Psikotest LolosPsikotes BVKAinda não há avaliações

- Logic Puzzles Freebie: Includes Instructions!Documento12 páginasLogic Puzzles Freebie: Includes Instructions!api-507836868Ainda não há avaliações

- SDLC - Agile ModelDocumento3 páginasSDLC - Agile ModelMuhammad AkramAinda não há avaliações

- Reconsidering Puerto Rico's Status After 116 Years of Colonial RuleDocumento3 páginasReconsidering Puerto Rico's Status After 116 Years of Colonial RuleHéctor Iván Arroyo-SierraAinda não há avaliações

- INTERNSHIP REPORT 3 PagesDocumento4 páginasINTERNSHIP REPORT 3 Pagesali333444Ainda não há avaliações

- Dwi Athaya Salsabila - Task 4&5Documento4 páginasDwi Athaya Salsabila - Task 4&521Dwi Athaya SalsabilaAinda não há avaliações

- Life and Works of Jose RizalDocumento5 páginasLife and Works of Jose Rizalnjdc1402Ainda não há avaliações

- P7 Summary of ISADocumento76 páginasP7 Summary of ISAAlina Tariq100% (1)

- Richard CuretonDocumento24 páginasRichard CuretonHayk HambardzumyanAinda não há avaliações

- Al-Rimawi Et Al-2019-Clinical Oral Implants ResearchDocumento7 páginasAl-Rimawi Et Al-2019-Clinical Oral Implants ResearchSohaib ShujaatAinda não há avaliações

- Numl Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016Documento1 páginaNuml Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016sajeeAinda não há avaliações