Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Picture Words: Toward An Art-Critical Methodology

Enviado por

James McArdleTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Picture Words: Toward An Art-Critical Methodology

Enviado por

James McArdleDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Name: James McArdle, Senior Lecturer in Visual Arts, La Trobe University

Title: Picture Words: toward an art-critical methodology

Abstract: Phiction: Lies, Illusion and the Phantasm in Australian Photography is a curatorial experiment in

assembling a survey exhibition from a significant collection. Its formulation, presentation and the outcomes of

its tour of eleven regional and metropolitan Victorian galleries provide a case study for this paper. The

exhibition Phiction (the title amalgamates photography and fiction) challenges audiences reading of

photographs, and confronts some curatorial assumptions, by juxtaposing the images with extracts of Australian

fiction instead of the usual gallery fact sheet, list of provenance or expert gloss. In this way the exhibition forces

a confrontation between dumb image and blind text and while examples are examined, a review of the

exhibition is not the purpose of this paper. A consideration of its process and effect is discussed in the paper to

propose a comparative tool in the study, investigation and evaluation of art. It is offered to visual art school

researchers, lecturers and students contemplating the most appropriate and effective, or alternative,

methodologies to employ. With reference to the dominant systems of critique that have come to us from other

disciplines, the paper considers the art practitioners perspective by drawing on the example of Phiction to pose

the open question; How might we use one art form to explore another?

Biography: James McArdle is an artist whose area of research is the difference between human perception and

camera vision, concentrating on focus and binocular vision. His practice exploits this difference for

expressive and aesthetic purpose and he has exhibited since 1974, most recently in 2002/2003 at Bendigo and

Horsham Regional Art Galleries. He has regularly presented papers related to this research at national and

international conferences. He is currently part time Senior Lecturer in PhotoPrintMedia at La Trobe University

Bendigo coordinator of Postgraduate studies, and concurrently is senior partner in a freelance photography

business specialising in fine art reproduction, photojournalism and corporate work. He has twenty years

experience in art education and administration at a tertiary level that includes positions at Victoria University

(Prahran, now Victorian College of the Arts), RMIT, and Monash and La Trobe Universities. He has also

lectured in private institutions (Council of Adult Education, Photography Studies College, and the Australian

College of Photography, Art and Communication). He has curated exhibitions of photography including the

currently touring Phiction: Lies Illusion and the Phantasm in Photography and The Edge which brought

together contemporary photojournalistic and documentary images of deviance and transgression from South

Africa. He is completing a PhD at RMIT.

Words represent images: nothing can be said for which there is no image. Fredrick Sommers1

statement is arguable, but in a conference that brings together lecturers from art and design courses within

universities, it is one that we might embrace as a slogan as we put the case for the legitimacy of our teaching

and research in institutions that value words more than images. The purpose of this paper is to extrapolate from

the personal experience of developing an exhibition with a curatorial innovation that combined fiction and

visual representation, to propose a possibility for a comparative tool in the interpretation and investigation of

art.

Most likely, it was my position as Lecturer in Photography and familiarity with my practice, rather than

my reputation as a curator, that prompted Merle Hathaway, director of the Horsham Regional Art Gallery to ask

me to assemble photographs from their collection for a touring exhibition. Our proposal successfully attracted a

Victorian Government grant to tour the exhibition to eleven regional and metropolitan galleries.

The role of curator I understand is to care, and to find some means to encourage others to care, about

the art placed in our charge. The starting point was to select representative images from the collection of more

than 2,000. Horsham Regional Art Gallery specialises in the collection of diverse examples of Australian

photography to the point where its holdings are larger than most metropolitan institutions. Some are

documentary or photojournalistic, not all have an artistic intent.

The exhibition was going to a range of public galleries with a general audience. In seeking a common

thread by which to draw together the works for the show I decided to exploit two clichs; The camera never

lies assumes photographs are documentary and factual, and the old saw "One picture is worth a thousand

words begs to be questioned because its simplistic formula assumes that some quantifiable exchange can be

made of words with pictures. The latter phrase was coined by Fred R. Barnard2 , a pioneer of images in

advertising (it is significant that he subsequently inflated his original equation to "One picture is worth ten

thousand words" in 1927). It also declares an inter-change between pictures and words, which is something else,

and that is what I would really like to consider here.

The problem of the equivalence between word and image is exhaustively disputed, not least by the

semioticians, like William Mitchell

[W]e still do not know exactly what pictures are, what their relation to language is,

how they operate on observers and on the world, how their history is to be understood, and

what is to be done with or about them. 3

This paper is not a review of Phiction: Lies, Illusion and the Phantasm in Photography, which would

be a pointless exercise in self-congratulation (or self-flagellation). In addition, I am a photographer and not a

semiotician. Instead I will draw from the presentation of works from Phiction (the title amalgamates

photography and fiction) and emphasise the way we might read photographs, using some correspondence

between the meaning contained in a photograph and that transmitted, for instance, by 'a thousand words', which

is roughly the amount contained in a long newspaper feature or a very short story. I want to extrapolate from

that to pose an open question; How might we use one artform to explore another?.

We are used to seeing photographs accompanied by text or captions, but where is there any point of

comparison between text and image? Phiction tests the connection in three ways.

First, in this exhibition, texts accompany the images which are not the usual gallery fact sheet, list of

provenance nor curatorial gloss, but exclusively small extracts from Australian fiction, most not even two

hundred words long. I intend that the use of these novels and stories should encourage and challenge the viewer

to question the image. The largest part of my work as a curator was to seek out from memory of my own

reading, texts which seemed to connect with the images.

Secondly, Phiction presents images that are not easily explained and challenge the viewer for

interpretations. Many are illusionistic, some deliberately lie, pretending to be something they are not, some even

are apparitions. Their fictionality readily challenges the assumption that The camera never lies.

Lastly, no text and image pair is an exact 'fit' since none of the writers intended their writing as a

caption, and none of the photographers was illustrating the text. In this way, the exhibition forces a

confrontation between the dumb image and the blind text. Such lack of exact correlation prompts the viewers

to substitute it for their own reading to decide for themselves if photographs are lies, illusions, or phantasms.

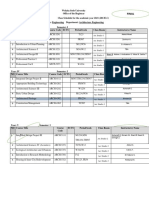

We surveyed visitors to the exhibitions of phiction at nine venues to date across urban and regional Victoria.

Invariably, whether they are students from across the range primary to tertiary, or members of the public, there

is universally a readiness make the connection between each image and its caption. From audiences making

such considerations come many questions about intentionality and aesthetic merit in both photograph and

printed word. The important question here is; What more might a process of comparison texts and images, or

images and performance, or a dialogue of works from any of the art forms, contribute as a methodology in Art

and Design courses? That is to say, that while here I may limit my comparison to photographs and works of

fiction, I propose that much of value may come when Visual Art students and researchers undertake such

comparative studies.

It was my aim to suggest that photography is a form of language and of writing. Of course the visitors

to this exhibition almost certainly have made and used photographs for themselves and therefore fulfil the wellknown prophecy made in 1936 by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy: The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant

of the use of the camera as well as of the pen.4

Often used as a mnemonic, a means of assisting our

fading memories, photograph is 'the mirror with a memory';

the Kodak moment in the family album. Sometimes our only

recollection of an event is the photograph. Might the

photograph even be used to supplant memory, replacing it

with something that has equal veracity, but in fact being a

persuasive fiction, an implanted memory'? In an exhibition

dealing with images which deliberately mislead or puzzle the

viewer we can see that photography allows the possibility of

'constructing' a revelation; a moment when the viewers

memory is altered to include an episode created by the

narrative union of found text and real photographs. For Figure 1 Sandy Edwards, New Zealand, Australia b.1948,

any photographer the problem, and the beauty, of the Marina Meets Horizon c.1988-95 silver gelatin

photograph, 23.2 x 34.5 cm

medium is its capacity to leave things out. It is ready-made

for the little white lie, the one where you leave something that may incriminate you unsaid. Somewhere out of

frame, offstage, the moment before or after the photograph was taken lies a truth that the photographers prefer to

replace with their own account.5

Cinema, a narrative comprising the spoken word and moving image, might be a useful comparator. Its

flow of narrative follows only the arrow of time. Presenting still images with text allows reflection between

images and other images, between images and text. It allows the possibility of reordering the reading.

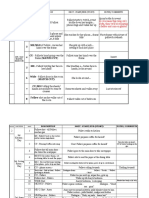

Carlo Golin's sequence of photocopies (1999)

headlines the invitations for Phiction and is a useful entre. It

is equally a text and an image. They are letters in presented in a

medium that is normally used to duplicate the words of other

authors. Here is one letter at a time, one in each image.

However, they are more than letters. They are copies of

Figure 2 Carlo Golin , Australia b.1948, ONCE 1999,

laser print 26.8 x 17.8 cm

photographs of letters that existed somewhere in three

dimensions. Perhaps they appeared on the wall of an Art Deco

cinema and were prised off, leaving only their outlines, so they are in fact not even letters. Most likely they were

not originally

the sequence

'N', 'C' and 'E' but assembling them in this order Golin suggests a story about

Old in

Mission,

Victoria'O',

1979

these

corroded

letterforms.

A

simple

narrative, it is the story that begins, as long ago we used to hear, "Once

silver gelatin photograph

Upon a Time" that trails off, leaving us with the onus of providing a history for these lost letters. In the

25.7 x 18.8Barry

cm Humphries story deals also with a sequence of letters:

exhibition

One night in about I943 I heard them playing 'Sweet Spirit', a psychic parlour game

in which I was never allowed to participate. An alphabetical circle was arranged on the table

top and everyone put their finger on an upturned glass in the middle. They all took it in turns

to ask the spirit questions, and there were always crescendos of laughter followed by, 'Shhh,

you'll wake the children.' My father was regularly reproached for cheating. One night I heard a

voice, I think it was Aunty Dorothy's, ask the spirit when Cliff Jones, Phyllis's brother, was

coming home on leave, and there was a strange silence in the room as the glass, carrying

everyone's fingers with it, darted from N to E to V to E to R. They never played that game

again.6

In the photograph, as in the text, the letters are a loaded quotation and this similarity emphasises the

differences. Photographs reveal, show, appear; words describe, narrate, announce. There is a difference in their

import, in the freight of their contents, in their intelligence.

Words are read in sequence. Photographs can be taken in by the eye all of a piece, for which they may

compose para-frames in sub-clauses. They might present for instance, in one image, a shattered wall with a

window on nothing, a blurred dog, and the rusted iron fence around a grave. Trevor Kenyon's photograph of the

'Old Mission' (1979) allows that these components, though seen all at once, may be connected with each other in

several permutations. The meaning of this photograph is a sum of these parts, an equation we make for

ourselves within the bracket of his framing. We are provided with alternatives for the very environment of this

image. Will the propped wall fall away to reveal lush forest, or the stark sky that the window frames? Which is

the true time scale of this image? Is it that of the departing dog or that which ages with the grave? Set against

this are the neatly punctuated clauses from Colleen McCulloughs The Thorn Birds which pace out the

memorials and mounds in Drogeda station graveyard

But perhaps a dozen less pretentious plots ringed the mausoleum, marked

only by plain white wooden crosses and white croquet hoops to define their neat

boundaries, some of them bare even of a name: a shearer with no known relatives who

had died in a barracks brawl; two or three swaggies whose last earthly calling place had

been Drogheda; some sexless and totally anonymous bones found in one of the

paddocks; Michael Carson's Chinese cook, over whose remains stood a quaint scarlet

umbrella, whose sad small bells seemed perpetually to chime out the name Hee Sing,

Hee Sing, Hee Sing, a drover whose cross said only TANKSTAND CHARLlE HE

WAS A GOOD BLOKE; and more besides, some of them women.7

Text and image illuminate each other because they share not only imagery but

also phraseology.

In asking But isnt a photographer who cant read his own pictures worth less

Figure 3 Trevor Kenyon,

8

than

an

illiterate?"

, Walter Benjamin reminds us that photographers themselves use

Australia b.1948 O l d

words to explain, describe, or title their images. When left to the fine art photographer

Mission, Victoria 1979

silver gelatin photograph the shared sense between image and title, most often noun phrases, is left deliberately

25.7 x 18.8 cm

enigmatic, as in The Fall of the Shadow, The Ascent, The Harmed Circle, or

Patterns of Connection. Embraceable You leaves us looking for the beloved, only to find that there are two

sets of arms and one body. These titles, in their provocative mystification, would be equally fit for poems, and

like the titles of poems, they are themselves figures of speech, or images.

The titles of documentary images reflect their indexical nature, mapping for us Vale Street, the Old

Mission, Victoria, or Cox and Rizzetti Foundry, Melbourne, characterising Young Couple with Torana, or

explaining Imprisoned in Ice, January 1915. However some titles deliberately confuse the conventions and

we should beware of categorising Corrugated Iron Fence with Hole when it turns out to be less concerned

with surface appearances than with the metaphoric void of the hole.

Likewise, Frank Hurleys Imprisoned in Ice, January 1915, an iconic

representation of the doomed Shackelton Expediton ship Endurance is more than

document, a metaphoric double-take that lets us see the expeditioners vision of

their vessel in the high waves made futile as the billows freeze solid. It is full of

artifice in its mannered composition, and this sits among a body of prints in

which Hurley recombines several views of the ship, skies and ice in ever more

dramatic montages that elaborate the event, though here such artistry is restricted

to the blue-toned carbon print. Seventy years later comes another stranding in

Glenda Adams novel

Figure 4 Frank Hurley, Australia

"I wish I had a camera?" said Donna, her voice 1885-1962, Imprisoned in Ice,

January 1915 1915 blue toned

muffled by her scarf.

Lark stopped crying and sat beside her. The tears were carbon photograph 38.9 x 49.1 cm

still wet on her cheeks, her eyes were fixed on the ship.

"They're going to leave us behind."

"I'd reckon we have about two hours until the reef is covered and we can't stand any

more?" said Donna. As she spoke, the water was lapping again at their toes and soon was

covering their feet.

"Like those galloping tides in England?" said Donna chattily. "The shore is so flat

that the sea just rushes in at high tide, like a train. People are always drowning, trying to run

away from it. You have to somehow not fight it, but go with it, go with

whatever is pushing at you, in order to master it."

They stood up and picked their way to what appeared to be the

highest part of the reef. Donna had now let her glass bowl go and was

leading Lark. Even at the highest point the water was at their ankles,

rising steadily.9

Adams text and Hurleys image share more than a common theme. The episode

in Walking On Coral is literally pivotal, positioned at the exact centre of the book in

demonstrating symmetrical changes in the lives of all protagonists. The artifice of both

works makes them iconic.

We expect our curiosity about journalistic images to be mollified by a caption

rather than a mere title that is intended to whet our appetite for an accompanying article.

Significantly, such captions as Fierce Storm Strikes Horsham are in the same nonprogressive present as photography itself.

Figure 5 Australia

b.1935, Untitled (The

Big Bang) 1978 silver

gelatin photograph,

40.6 x 30.6 cm

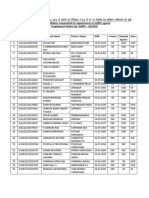

Included in the exhibition are newspaper images from Ian Ward, self-taught press photographer with

The Wimmera Mail-Times, Horsham's local paper. Both images are typical of his conscientious approach, rare

amongst Australian regional newspaper photographers. Lifted off the newsprint, and presented by Ward with

new Art (noun phrase) titles for the exhibition they become strange images that prompt astonishment at

strange truths, a puzzle that demands solution. Such a 'puzzle test' should be applied to any photojournalistic

image. A tight vertical composition, reinforced by a witty directional arrow that is a galvanised shed, adds a

figurative megaton to the explosive force of 'Lift Off'. A puzzle with explosive consequences is also at the

centre of the accompanying Eucalyptus: A Novel by Murray Bail.

The written equivalent of the portrait is the biography. If portraitists would

present us with their subjects' life story they remain aware that a photograph extracts

a mere moment from that story, so that the portrait photograph which has been

linked so often to mortality10, is like the corpse of its subject, or more like its

elaborate sarcophagus. How can this be when it is so easy to believe in the life in

these photos? The act of portrayal through photography is close to death in that it is

like a eulogy, but it is at the same time a conversation. Robert Billington's 'Young

Couple With Torana' (1992) is documentary and its protagonists speak directly to

us.

The nineteenth century concept that 'every face tells a story' is true insofar

as we accept that it is a story and that the representation can be honest or dishonest,

portrayal or betrayal. Beyond the likeness, in a photograph, the 'moral dimension'

Figure 6 Robert BILLINGTON

Australia Young Couple with becomes a visual exchange using as currency all the metaphor that can be assembled

Torana (from the book Rustic

in the image. In this way, what starts as a document becomes a contract between

Paradise) 1992, silver gelatin

sitter and photographer and ends up looking as much like fiction as a 'predictive'

photograph, 40.6 x 40.5 cm

biography, if there might be such a thing.

Here are other arresting images of people's faces, by Bill Henson, Julian Smith, and Joyce Evans.

However, do they pretend at portraiture? The majority of the images in this exhibition come from the period

from mid 1970s to the 1990s when the medium was gaining

ascendancy in the visual arts in Australia. I think the very moment

where we can see this happening is in 1975 as the young woman in

Carol Jerrems' triple portrait gazes into our eyes, barefaced against the

late afternoon light, while her companions hang back watchfully in the

shadows. She would be candidly at home, it seems, amongst the cinema

verit cast of Helen Garner's novel, 'Monkey Grip' (1977) and indeed

she coexisted in the same Melbourne. Both image and book purport to

an autobiographical honesty on the part of the authors. However, this

woman and her dark companions are co-conspirators with Jerrems in Figure 7 Carol JERREMS, Australia 1949forging what would seem to be a another document in the by then 1980 Vale Street 1975, silver gelatin

mannerist manifestation of the street photograph, a form pursued with photograph, 20.2 x 30.2 cm

particular vigour by Jerrems in her edgy series on the skinheads. In fact, this woman, Catriona Brown is an

actor who poses in Jerrems 'Vale Street' (1975). The men, whom Brown had never met before, were members

of the skinhead gang, some of whom, it is said, had once raped Jerrems. The photographer was inspired by

working at the time with director Paul Cox on his early films. This Arbus-like confrontation is part fiction; the

extract that accompanies the photograph here is from Helen Garner's celebrated story, which is part

autobiography. Both the novel and the photograph move art, through feminisms left field, into post-modern

reinvention. Photography was the medium that took a leading role in bringing this new sensibility to prominence

in Australian art practice.

Our house was full again, people home from holidays, but the summer still standing

over us. We climbed the apricot tree in the hack yard and handed down great baskets full of

the small, imperfectly shaped fruits. Georgie made jam. Javo and I sat in the sun on the

concrete outside the back door, cracking the apricot stones with half bricks to get the kernels

out. I was learning how to reach him without talking, though

sometimes I was afraid he hadn't understood. We talked about this,

lying on my bed with our bare legs under and over.

'Don't worry,' he said. 'I like the way you love me. I feel

comfortable in it.'11

Deliberate fabrications or confections range from an emulsion on metal

assemblage by Ewa Narkiewicz, through Chris Barry's rephotographed collage to the

seamless photomontage of Peter Lyssiotis. A fabrication is a lie but alternatively a

construction, a 'built' image. The texts selected to accompany these images are Figure 8 Ewa NARKIEWICZ

Australia b.1961 Asparagus

fragments, just as the photographs are particles of time. Phiction is a montage in and Artichokes 1996, liquid

light photograph, 68.5 x 82.0

cm

which two art forms, the Australian novel and the Australian photograph overlap and invite direct crossreference.

An artist having works isolated for exhibition risks misrepresentation. Leah King-Smith had strong

words about that and they illuminate the problematic of conflating photograph and fiction, so her statement was

substituted for the original found text...

"The artist believes that the curatorial agenda of this exhibition is inappropriate if not

oppositional to her work. Her signature use of multi-layering is a means of addressing the

multi-dimensional quantum nature of reality, not the deceptive, non-existent or fearful nature

of reality that the exhibition title and brief suggests."12

In fact it was the incorporation of this King-Smith in an earlier show that I curated that provided the

inspiration for Phiction: Lies Illusion and the Phantasm in Photography. Literally, the reflection over this

appropriated historical photograph is one of King-Smiths own landscapes and we are left looking into multiple

layers, through history. The multilayering creates an illusion that contains its own disclosure. If we look through

it we will find in the old photograph a truth about a repression that is at the heart of our country. If we accept the

illusion it looks merely beautiful.

What would be an appropriate text for this important image? Might finding

one provide us with more insight than a direct and conventional interpretation,

analysis, or deconstruction?

The imposition of research and interpretative methodologies from other

fields on art is problematic precisely because they do not grow out of the practice of

art. Such a super-imposition might be the tradition of connoisseurship, a classification

and commodification of artworks as applied by collectors, not practitioners, that grew

into traditional Art History and High Art. Or it might be the more recent trend of

borrowing from quantum science concepts. Currently, Social Science visual culture Figure 9 Leah King-Smith

analysis through semiotics, quantity or discourse analysis, or psychoanalysis are Australia b.1957, Untitled,

from series Patterns of

approaches commonly used by visual arts researchers and higher degree candidates Connection 1991, colour

seeking to explain images. I am suggesting we interpret visual art images with other photograph, 108.0 x 108.0

art forms by a direct comparative association. We might use written fiction as in cm

Phiction, or we may employ any other art medium, including dance, song, or theatre. A survey of visual art

theses carried out in the UK shows that comparative research constitutes but one percent of the most commonly

used methodologies in visual art research13. Comparative association, proposed here, recognises that we might

relate an understanding of art in artistic terms, in language when such language is art, as in poetry, or even

without words at all. Art is experience, a moment of communion. How easy to strip it bare with a few careless

words!

1 Sommer, Fredrick, The Poetic Logic of Art and Aesthetics (Stockton, NJ, Carolingian Press, 1972), page 2.

2 Barnard, Fred R., Printers Ink, 8 Dec., 1921: page 96 and Printers' Ink, 10 March 1927

3 Mitchell, William J. T. Picture Theory: essays on verbal and visual representation, (London Univ. of Chicago

Press, 1994), page 11.

4 Lazlo Moholy-Nagy quoted in Traub, Charles (ed.). The New vision : forty years of photography at the

Institute of Design (Millerton, N.Y : Aperture, inc, c1982), page 23.

5 I elaborate on the lie in Fuhrmann, Andrew. Phiction and Lies: Andrew Fuhrmann Interviews James McArdle,

La Trobe Forum, Number 22, Winter 2003, p 40-43

6 Humphries, Barry. More Please: An autobiography (Australia, Penguin Books, 1992) Page 97

7 McCullogh, Colleen. The Thorn Birds, Harper and Row (Australasia) 1977 p.115

8

Benjamin, Walter (translated by Patton), A. A Short History Of Photography, 1931, in Trachtenberg, A. ed.,

Classic Essays on Photography. (New Haven USA: 1980), page 199.

9 Adams, Glenda. Dancing On Coral, (Australia: Angus and Robertson 1987)

10 Elaborated in Metz, Christian 'Photography and Fetish', October no.34 Fall 1985 (Cambridge, Mass. : MIT

Press)

11 Garner, Helen. Monkey Grip (Melbourne: McPhee Gribble Publishers, 1977).

12 King-Smith, Leah. Quoted from email to director Merle Hathaway, Horsham Regional Art Gallery dated

Tuesday, October 09, 2001 8:53 PM

13 from Allison Research Index of Art & Design, 1992, used in Carole Gray and Ian Pirie Artistic Research

Procedure: Research at the Edge of Chaos (The Centre for Research in Art & Design, Gray's School of Art,

Faculty of Design, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK., 1995), p.8

Você também pode gostar

- Teacher's - Book - LONGMAN - Repetytorium - Maturalne - Język - Angielski - Poziom - RozszerzonyDocumento4 páginasTeacher's - Book - LONGMAN - Repetytorium - Maturalne - Język - Angielski - Poziom - RozszerzonyMagda Kwiatkowska18% (11)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- WWW Koimoi ComDocumento10 páginasWWW Koimoi ComMclin Jhon Marave MabalotAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Articles: Practice Set - 1Documento4 páginasArticles: Practice Set - 1Akshay MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Soal UAS 1 OkDocumento8 páginasSoal UAS 1 OkLaila FazaAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- EJF2014Documento32 páginasEJF2014Dragos PandeleAinda não há avaliações

- Types of Cameras PPPDocumento19 páginasTypes of Cameras PPPLakan BugtaliAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Forgiveness EssayDocumento3 páginasForgiveness Essayapi-387878383100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- EXTRACT - The Truth About The Harry Quebert AffairDocumento23 páginasEXTRACT - The Truth About The Harry Quebert AffairKristy at Books in Print, Malvern0% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hunter 2012 Unlock All Animals PDFDocumento3 páginasThe Hunter 2012 Unlock All Animals PDFCorneliusAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Philippine Possession and PoltergeistDocumento12 páginasPhilippine Possession and PoltergeistYan Quiachon BeanAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Assigment of literacture-WPS OfficeDocumento4 páginasAssigment of literacture-WPS OfficeAakib Arijit ShaikhAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- We Wish You A Merry Christmas Harp PDFDocumento4 páginasWe Wish You A Merry Christmas Harp PDFCleiton XavierAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Arc 2013 1st Sem Class Schedule NEW 1Documento2 páginasArc 2013 1st Sem Class Schedule NEW 1Ye Geter Lig NegnAinda não há avaliações

- James Chapter 1 Bible StudyDocumento4 páginasJames Chapter 1 Bible StudyPastor Jeanne100% (1)

- Yoga Therapy & Integrative Medicine: Where Ancient Science Meets Modern MedicineDocumento11 páginasYoga Therapy & Integrative Medicine: Where Ancient Science Meets Modern MedicineAshu ToshAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- 07 Story of Samson and Delilah - Judges 13Documento9 páginas07 Story of Samson and Delilah - Judges 13vivianstevenAinda não há avaliações

- Liturgy Guide (Songs W CHORDS Latest) With Prayers 2Documento33 páginasLiturgy Guide (Songs W CHORDS Latest) With Prayers 2Keiyth Joemarie BernalesAinda não há avaliações

- Tymology: Names of JapanDocumento3 páginasTymology: Names of JapanDeliaAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Why Art Hacking Is The Most Fundamental Skill - Stephane Wootha RichardDocumento54 páginasWhy Art Hacking Is The Most Fundamental Skill - Stephane Wootha Richardthebatwan100% (1)

- 14 PatolliDocumento8 páginas14 PatolliCaroline Martins Nacari100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Vf/Klwpuk La ( K, L-VKB@JSLQC & 02@2018 Ds Varxzr Mi Fujh (Kd@Js-Lq-C-Ds in Ij Fu QFDR GSRQ Lwphcèn Meehnokjksa DH LWPHDocumento7 páginasVf/Klwpuk La ( K, L-VKB@JSLQC & 02@2018 Ds Varxzr Mi Fujh (Kd@Js-Lq-C-Ds in Ij Fu QFDR GSRQ Lwphcèn Meehnokjksa DH LWPHShiva KumarAinda não há avaliações

- English Form 4Documento13 páginasEnglish Form 4Yat CumilAinda não há avaliações

- How To Play Single Notes On The HarmonicaDocumento19 páginasHow To Play Single Notes On The HarmonicaxiaoboshiAinda não há avaliações

- The Onions BassDocumento3 páginasThe Onions BassBoatman BillAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- 1586 5555 1 PBDocumento17 páginas1586 5555 1 PBAligmat GonzalesAinda não há avaliações

- Stockings in Runaway Ads DickfossDocumento12 páginasStockings in Runaway Ads Dickfosseric pachaAinda não há avaliações

- Event Management Checklist PDFDocumento3 páginasEvent Management Checklist PDFyusva88Ainda não há avaliações

- Footprints in The SandDocumento1 páginaFootprints in The SandFailan MendezAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Sad I Ams Module Lit Form IDocumento38 páginasSad I Ams Module Lit Form ImaripanlAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 6 Small GroupDocumento2 páginasLesson 6 Small GroupMark AllenAinda não há avaliações