Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Anti Vegf Drugs in The Prevention of Blindness

Enviado por

Indra PermanaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Anti Vegf Drugs in The Prevention of Blindness

Enviado por

Indra PermanaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DRUGS

Anti-VEGF drugs in the

prevention of blindness

David Yorston

Consultant Ophthalmologist: Tennent

Institute of Ophthalmology, Gartnavel

Hospital, Glasgow, UK.

dbyorston@btinternet.com

Disorders of the blood vessels in the

retina are responsible for some of the

most common causes of blindness in the

world. These include:

retinopathy of prematurity (an important

cause of blindness in children in middleincome countries)

diabetic retinopathy (the most common

cause of blindness in the working-age

population of industrialised countries)

age-related macular degeneration (the

third most common cause of blindness

in the world).

All of these conditions are caused partly

by over-production of a protein called

vascular endothelial growth factor

(VEGF). This protein was discovered in

the 1980s and is important in the growth

and development of blood vessels. VEGF

production is increased by hypoxia (a lack

of oxygen). So, if a tissue is not getting

enough oxygen, it will produce more

VEGF, which will stimulate the growth of

additional blood vessels to provide more

oxygen. This is beneficial in the heart

muscle, or in a growing baby; however, in

the eye it can be harmful.

The effects of VEGF may be summarised as:

Increased permeability of existing blood

vessels, causing them to leak.

Growth of new blood vessels, which may

bleed or leak fluid and proteins.

In the eye, both can lead to retinal

damage.

Normal retinal capillaries (very fine

blood vessels in the retina) are sealed

thanks to tight junctions between the

cells making up the capillary walls. This

means that large molecules, such as

proteins and lipids, cannot leak out of

these retinal capillaries into the retina. In

the presence of excessive VEGF, however,

the capillaries start to leak and large

molecules form exudates and escape into

the retina, causing oedema in the

surrounding tissues. If this affects the

macula, then the central vision will be

reduced. This is what causes diabetic

macular oedema.

Excessive VEGF also causes the growth

of new, abnormal retinal blood vessels

and capillaries. These do not grow within

the retina, where they might be useful.

44

Instead, the abnormal capillaries grow out

from the retina onto the surface of the

vitreous, where the vitreous touches the

retina. This happens in proliferative

diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of

prematurity. The new vessels are fragile

and prone to tearing. When a new vessel

is torn, it bleeds, causing vitreous

haemorrhage. As the vitreous contracts,

the new vessels pull on the retina,

causing a traction retinal detachment. If

the detachment includes the macula,

vision will be impaired.

In the presence of excessive VEGF, new

vessels can also grow out from the choroid

(the layer immediately under the retina).

These new vessels grow into the space

between the retina and the choroid,

usually just under the retinal pigment

epithelium. The newvessels leak exudates

formed of fluid or blood, causing oedema;

eventually a fibrous scar is formed that

destroys the photoreceptor cells at the

centre of the macula. This is what

happens in exudative (or wet) age-related

macular degeneration (AMD).

Because of these very damaging

effects in the eye, researchers have been

working for years to find a way to block the

activity of VEGF in the eye.

Anti-VEGF drugs

VEGF has many beneficial effects in the

rest of the body. Therefore, any

anti-VEGF drug has to be given by a route

that gives the maximum effect in the eye,

but little or no effect elsewhere. In

practice, this means it must be injected

into the eye (intraocular injection). This

carries a number of risks, and it is

thought that about 1 in every 1,000

injections has a serious complication

such as cataract, vitreous haemorrhage,

retinal detachment, or infection. Each

injection must be handled with appropriate sterilisation and aseptic technique

(see page 47).

The two most widely used drugs at

present are Lucentis (ranibizumab) and

Avastin (bevacizumab). Both drugs are

monoclonal antibodies that bind to all

three forms of VEGF. They are very similar

drugs (see page 48), but Lucentis is a

smaller molecule and is believed to bind

VEGF in the eye with greater affinity.

Lucentis is intended purely for intraocular

injection, and each vial can only be used

for one patient. Avastin was intended to

be given intravenously as an anti-cancer

drug, and comes in vials of 100 mg.

As the dose required for intravitreal

COMMUNITY EYE HEALTH JOURNAL | VOLUME 27 ISSUE 87 | 2014

injection is only 2.5mg, one vial of 100 mg

of Avastin can be used to treat 40

patients, provided that you have the

necessary skills and facilities to prepare

sterile injections for intraocular injection.

In the United Kingdom, the British

National Formulary gives a net price of

242* for a 100 mg vial of Avastin,

(containing 40 doses). The British

National Formulary gives a net price of

742* for a single 2.5 mg dose of

Lucentis. This means that a single dose of

Avastin can work out to be over 100 times

cheaper than a single dose of Lucentis

(provided that you have the skills and

facilities, as stated above). [*Note: The

actual prices of drugs vary considerably

due to local purchasing arrangements,

and may be very different from the net

prices quoted above. These are taken

from the British National Formulary, and

only give an indication of the relative costs

of the drugs.]

The most recently approved drug is

aflibercept (also known as Eylea). This is

an artificial protein that contains the VEGF

receptor molecules that are normally

attached to cell membranes. The VEGF

binds to these receptors and is trapped

and rendered harmless. Aflibercept

seems to be as effective as Avastin and

Lucentis, but may be given less frequently.

In the British National Formulary, a single

dose has a net price of 816.

Side-effects

VEGF is important for the growth of new

blood vessels. Although the dose of

anti-VEGF needed to treat eye diseases is

very small, it has been shown to reduce

the level of VEGF in the bloodstream. This

means that there is a theoretical risk that,

in adults, anti-VEGF drugs may increase

the risk of cardiovascular disease,

including heart attacks and strokes.

However, clinical trials have not shown

conclusive evidence of an increased risk

of cardiovascular disease in patients

treated with anti-VEGF drugs compared to

those given sham injections.

In babies and young children, VEGF is

essential for the growth of blood vessels

and normal growth and development of

many other organs including the lungs,

kidney and brain. This is one of the

reasons why anti-VEGF drugs are

absolutely contra-indicated in pregnancy.

Women of childbearing age should have a

pregnancy test prior to starting treatment,

and must avoid pregnancy during

treatment. Although Avastin has been

Treatment regimes in adults

Regardless of the treatment indication,

there are essentially two regimes for

administering anti-VEGF drugs:

continuous and intermittent/as

required (or pro re nata, PRN for short).

Most of the initial trials were done as

a continuous regime, with regular

monthly injections over the course of 2

years, i.e. patients would have 24 injections in total. These trials showed that

treatment delivered in this way was

effective, but it is also expensive and

inconvenient for both the patient and the

health care provider.

A number of other trials have examined

PRN regimes. These are all fairly similar

and consist of three injections given over

3 months, followed by review. At this point

the patient may:

be much better, in which case no

additional treatment is needed

have no improvement at all, in which

case further treatment is futile

have some improvement, which would

justify further injections.

Even among those patients who do very

well, and do not require more than three

injections initially, many will relapse and

require further injections in the future.

This means they must be regularly

reviewed in the clinic, i.e. every 12

months, which involves testing of visual

acuity and/or retinal thickness. If patients

visual acuity is lower by one or more lines,

or if they develop worsening macular

oedema, they need a further injection of

anti-VEGF.

Trials of this dosing regime for AMD and

diabetic macular oedema have shown

that an average of seven injections are

required in the first year of treatment and

that outcomes are as good as for regular

monthly injections. The trials used as their

indication for re-treatment with anti-VEGF

either a reduction in visual acuity or an

increase in retinal thickness (measured

using optical coherence tomography

[OCT]); both were assessed at each visit.

While visual acuity is easily measured,

retinal thickness can only be measured

accurately by OCT. These machines are

costly and will only be available in major

Continues overleaf

FROM THE FIELD

Use of anti-VEGF drugs at the Instituto de

la Visin de Montemorelos

Pedro A Gomez Bastar

CBM Medical Adviser and Chairman, Instituto de la Vision, Universidad de

Montemorelos, Mexico pgomez07@gmail.com

1 Which antiVEGF agents

do we use?

Pedro A. Gomez Bastar

used in the management of retinopathy of

prematurity, its use is controversial,

because of the potential for serious

adverse effects when used in young

babies (see panel on page 46).

In practice, the major adverse effects

of these drugs appear to be associated

with the intraocular injection rather than

the active drug.

We use bevazucimab

(Avastin) the dose

used is 2.5 mg (0.1 ml).

This anti-VEGF agent is

used because of its:

proven efficacy and

effectiveness (CATT &

IVAN studies)

low cost, making it

affordable for our

patients.

Anti-VEGF injections are given in a clean room

5 What are the outcomes?

2 What are the

indications?

Vitreous haemorrhage secondary to

proliferative diabetic retinopathy

particularly when there has been no

previous laser.

Prior to vitrectomy for proliferative

diabetic retinopathy.

Clinically significant macular oedema

due to diabetic retinopathy.

Macular oedema secondary to branch

or central retinal vein occlusion.

Exudative age-related macular

degeneration.

Neovascular glaucoma.

3 Who gives the

injections?

Intra-vitreal injections are always given

by an ophthalmologist, for example:

retina specialists

retina subspecialty trainees

ophthalmology residents in the retinal

service.

4 Are anti-VEGF agents

used without OCT?

Anti VEGF agents are used without OCT

in selected cases:

vitreous haemorrhage secondary to

proliferative diabetic retinopathy

particularly when there has been no

previous laser

prior to vitrectomy for proliferative

diabetic retinopathy

clinically significant macular oedema

due to diabetic retinopathy

neovascular glaucoma.

Clinical experience has been very

positive and we believe this is a costeffective treatment for our patients.

Vitreous haemorrhage secondary

to proliferative diabetic retinopathy:

We have been pleased with our results.

Anti-angiogenic therapy reduces the

vitreous haemorrhage in many

patients with diabetic retinopathy,

allowing us to apply laser and avoid

vitrectomy surgery.

Prior to vitrectomy for proliferative

diabetic retinopathy: Application

35 days before surgery reduces the

risk of intra-operative and postoperative bleeding.

Neovascular glaucoma: In these

patients, we are careful to avoid further

increases in the IOP. When the rubeosis

regresses we apply pan-retinal laser,

giving us more control of the iris

neovascularisation.

Clinically significant macular

oedema: In clinically significant macular

oedema due to diabetic retinopathy, we

normally apply three doses of Avastin

with 1-month intervals between injections. After the last injection, a macular

OCT is requested and, if the oedema

has decreased, we apply focal laser.

Age-related macular degeneration

(AMD): In patients with exudative AMD,

an injection is given every month for

several months to improve visual acuity

and to control the disease, following the

treat and extend protocol.

Continues overleaf

COMMUNITY EYE HEALTH JOURNAL | VOLUME 27 ISSUE 87 | 2014 45

DRUGS Continued

cities in low- and middle income countries.

We dont yet know how effective PRN

treatment might be when retreatment is

guided by visual acuity alone, as both

visual acuity and retinal thickness were

measured at each visit in these trials.

Although intermittent regimes reduce

the number of injections, patients still

have to be reviewed every 12 months,

which leads to very busy clinics; this is

also a significant burden for the patients

and for their families.

Which diseases can be

treated?

Age-related macular degeneration

Lucentis, Avastin and Eyelea are equally

effective in exudative AMD. There

appears to be little difference between

monthly and PRN dosing. The average

(mean) improvement in vision is about

12 lines, and about one-third of

patients will improve by three or more

lines. With a PRN regime, an average of

seven injections will be required in the

first year. Most of these trials excluded

eyes with a vision of less than 6/96

(4/60), and treatment is unlikely to be

effective in advanced exudative AMD with

sub-macular scarring or a vision of

counting fingers or hand movement.

Unfortunately, exudative AMD often

co-exists with atrophic (dry) AMD, and

the anti-VEGF drugs only treat the

exudative component. With longer

follow-up (over 2 years), atrophic AMD

may cause a gradual loss of vision

despite effective anti-VEGF treatment.

Diabetic macular oedema

Once again, there seems to be little

difference between the different

anti-VEGF drugs. All three are effective at

treating diabetic macular oedema, and

the average improvement in vision is

about 1.5 lines. Roughly 25% of patients

will have their visual acuity improve by

three or more lines and 50% by two or

more lines. An average of seven injections

will be required in the first year of

treatment with a PRN regime.

Not all patients with diabetic macular

oedema need to be treated with

anti-VEGF. Laser treatment still has an

important role: macular oedema which

does not involve the fovea is best treated

with laser. These patients will normally

have good vision, and the laser will help to

preserve it. Moreover, laser is usually

effective with a single treatment, which is

much easier for the patient than repeated

monthly injections.

If new vessels are present, they should

be given pan-retinal laser treatment first,

before any macular oedema is treated

using anti-VEGF. This is because

anti-VEGF makes the new vessels regress

very quickly. As the treated vessels

become fibrotic, they contract, which can

cause a retinal detachment.

Retinal vein occlusion

There is good evidence from clinical trials

that all three anti-VEGF drugs will reduce

the risk of loss of vision following central

retinal vein occlusion. About 50% of

patients will gain three or more lines, with

a mean improvement of about two lines.

There is also a reduced risk of rubeosis

and secondary glaucoma with anti-VEGF

treatment.

Lucentis has been shown to improve

outcomes after branch retinal vein

occlusion as well. However, as many of

these patients will improve spontaneously,

this evidence is not quite as strong.

In summary, anti-VEGF drugs are probably

the most significant advance in ophthalmology in the last decade. They have

enabled us to treat what were previously

untreatable conditions. They are not a

perfect solution, however.

They do not cure the underlying

problem, so repeated treatment is

necessary and most patients will require

a lifetime of regular monitoring.

The drugs are expensive, and even highincome countries have struggled with the

costs and logistics of delivering thousands

of intraocular injections every year.

Although anti-VEGF drugs are the most

effective treatment for many retinal

diseases, the visual improvement is

modest, averaging about two lines of

vision. Relatively few patients will regain

normal vision.

Patients who present late, with very

advanced disease and a visual acuity of

less than 3/60, may not benefit from

treatment.

Most PRN treatment regimes rely on

OCT imaging, which is rarely available in

low and middle income countries. We

have little information on the use of

anti-VEGF in this setting, and we cannot

be sure that the good results achieved

in Europe and North America will be

replicated in Africa, India, or China.

Despite these reservations, anti-VEGF

drugs are going to play an increasing role

in the prevention of blindness worldwide.

As the global population ages, and

becomes more overweight, both AMD

and diabetic retinopathy will become

more common. The drugs will become

cheaper, and we may find better ways of

monitoring treatment so that expensive

OCT is no longer essential.

Anti-VEGF treatment for acute ROP not yet recommended!

Clare Gilbert

Co-director: International Centre for

Eye Health, Disability Group, London

School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine, London, UK.

There are several reasons why anti-VEGF

agents are not recommended for acute,

severe retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

There has only been one randomised

trial, which compared laser with

Avastin (bevacizumab) for Type 1 ROP.

It was only more effective in preventing

early recurrence of severe disease in

Zone 1 (posterior), but the recurrence

rate in the laser arm was worse than

would be expected based on other

studies. More babies died in the

anti-VEGF arm of the trial, but the

46

difference was not statistically

significant.

There are major concerns about the

short- and long-term impact of

anti-VEGF agents on the lung, kidneys

and brain of a baby.

Follow-up studies, using fluorescein

angiography, indicate that normal

retinal vascularisation may not take

place after administration of

bevacizumab, with extensive areas of

non-perfusion months after treatment.

There are an increasing number of

case reports which show that, although

Avastin can lead to regression of ROP

in the short term, the ROP can recur

months later. This means that an acute

disease with a known natural history

has the potential to become a chronic

COMMUNITY EYE HEALTH JOURNAL | VOLUME 27 ISSUE 87 | 2014

disease with an unknown and

unpredictable natural history.

Some surgeons use Avastin for Stage

4a or 4b ROP prior to surgery. This can

make the surgery easier, but there is

still the risk of systemic complications.

The leaking capillaries present in eyes

with retinopathy increase the risk of large

molecules (e.g. anti-VEGF drugs injected

into the eye) entering the systemic circulation, and so the systemic safety of

these drugs is important, particularly in

preterm infants. If anti-VEGF drugs seem

to be the only option to preserve sight

when extensive laser has failed, or the

infant is too sick for laser, this treatment

can be offered, but only after parents

have been fully informed of the possible

consequences.

The author/s and Community Eye Health Journal 2014. This is an Open Access

article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License.

Você também pode gostar

- Avastin Injection ConsentDocumento4 páginasAvastin Injection ConsentSaumya SanyalAinda não há avaliações

- 933 001abedi2013Documento7 páginas933 001abedi20136jprsrbhkcAinda não há avaliações

- Bevacizumab 21 A AdDocumento11 páginasBevacizumab 21 A Adbangun baniAinda não há avaliações

- Anti VEGFDocumento43 páginasAnti VEGFanantkumar85Ainda não há avaliações

- Review Article: Intravitreal Therapy For Diabetic Macular Edema: An UpdateDocumento23 páginasReview Article: Intravitreal Therapy For Diabetic Macular Edema: An UpdateRuth WibowoAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyDocumento9 páginasComparison of Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) With Triamcinolone For Treatment of Diffused Diabetic Macular Edema: A Prospective Randomized StudyBaru Chandrasekhar RaoAinda não há avaliações

- Uveitis Definition: C. Stephen Foster, M.DDocumento2 páginasUveitis Definition: C. Stephen Foster, M.DMasha AllahAinda não há avaliações

- Compounded BevacizumabDocumento6 páginasCompounded BevacizumabHenrique AquinoAinda não há avaliações

- A Collaborative Retrospective Study On The Efficacy and Safety of Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant (Ozurdex) in Patients With Diabetic Macular EdemaDocumento17 páginasA Collaborative Retrospective Study On The Efficacy and Safety of Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant (Ozurdex) in Patients With Diabetic Macular EdemaJosé Díaz OficialAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal 4Documento8 páginasJurnal 4Putri kartiniAinda não há avaliações

- Local Therapies For Inflammatory Eye Disease in Translation Past, Present and Future 2013Documento8 páginasLocal Therapies For Inflammatory Eye Disease in Translation Past, Present and Future 2013Igor VainerAinda não há avaliações

- Ma 2021 Uveitis 101Documento5 páginasMa 2021 Uveitis 101Jenny MaAinda não há avaliações

- Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in TheDocumento15 páginasDexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in TheMadalena AlmeidaAinda não há avaliações

- Choroidal NeovascularizationNo EverandChoroidal NeovascularizationJay ChhablaniAinda não há avaliações

- AVASTINDocumento10 páginasAVASTINFitri ShabrinaAinda não há avaliações

- HelmDocumento22 páginasHelmEga Gumilang SugiartoAinda não há avaliações

- Advances in The Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)Documento22 páginasAdvances in The Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)Ega Gumilang SugiartoAinda não há avaliações

- Glaucoma 9Documento13 páginasGlaucoma 9Sheila Kussler TalgattiAinda não há avaliações

- Brolucizumab PDFDocumento6 páginasBrolucizumab PDFCl WongAinda não há avaliações

- Intophthalmolclin2006462141 64Documento24 páginasIntophthalmolclin2006462141 64Laura BortolinAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Case Reports (ISSN:2572-8776) Loading Doses of Bevacizumab in Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO) : A Case ReportDocumento5 páginasInternational Journal of Case Reports (ISSN:2572-8776) Loading Doses of Bevacizumab in Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO) : A Case ReportPeony PinkAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Article 1861Documento12 páginas2017 Article 1861nanaAinda não há avaliações

- Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)Documento5 páginasRetinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)Rana PandaAinda não há avaliações

- Steps For A Safe Intravitreal Injection Technique - A ReviewDocumento6 páginasSteps For A Safe Intravitreal Injection Technique - A ReviewriveliAinda não há avaliações

- Pio y AntivegfDocumento14 páginasPio y AntivegfBernardo RomeroAinda não há avaliações

- Related ReadingsDocumento5 páginasRelated Readingscassandra cosAinda não há avaliações

- GP Factsheet - Steroids and The EyeDocumento6 páginasGP Factsheet - Steroids and The EyeBima RizkiAinda não há avaliações

- Porto Biomedical JournalDocumento7 páginasPorto Biomedical JournalzzakieAinda não há avaliações

- Ni Hms 707256Documento11 páginasNi Hms 707256iqbalAinda não há avaliações

- Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis: Why Is Allergic Eye Disease A Problem For Eye Workers?Documento3 páginasVernal Keratoconjunctivitis: Why Is Allergic Eye Disease A Problem For Eye Workers?darendraabimayuAinda não há avaliações

- Chronic EpididymitisDocumento4 páginasChronic EpididymitisAhamed RockAinda não há avaliações

- Difluprednato EC U S JOPT 2010 26 5 475 FosterDocumento11 páginasDifluprednato EC U S JOPT 2010 26 5 475 FosterMartin MauadAinda não há avaliações

- Case Vignette Macular DegenerationDocumento6 páginasCase Vignette Macular DegenerationJosh BlasAinda não há avaliações

- Uveitis PDFDocumento3 páginasUveitis PDFTri BasukiAinda não há avaliações

- What Do We Do About Diabetes?: See P 397Documento2 páginasWhat Do We Do About Diabetes?: See P 397Ika PuspitaAinda não há avaliações

- Anti VEGF Intravitreal InjectionDocumento26 páginasAnti VEGF Intravitreal InjectionAyesya KamilahAinda não há avaliações

- IncidenceDocumento11 páginasIncidenceNenad ProdanovicAinda não há avaliações

- Ret 1115 IDocumento24 páginasRet 1115 IeyheghedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Recent Advances Glaucoma ImplantsDocumento5 páginasRecent Advances Glaucoma ImplantsAnumeha JindalAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainDocumento6 páginas1 s2.0 S1091853116304438 MainMarcella PolittonAinda não há avaliações

- Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) Therapy For Persistent Diffuse Diabetic Macular EdemaDocumento7 páginasIntravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) Therapy For Persistent Diffuse Diabetic Macular EdemaJose Antonio Fuentes VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Intravitreal Injection of Bevacizumab: Review of Our Previous ExperienceDocumento6 páginasIntravitreal Injection of Bevacizumab: Review of Our Previous ExperienceShintya DewiAinda não há avaliações

- Neovascularization & EdemaDocumento3 páginasNeovascularization & EdemaKweku Grant-AcquahAinda não há avaliações

- Retinal Reperfusion in Diabetic Retinopathy Following Treatment With anti-VEGF Intravitreal InjectionsDocumento10 páginasRetinal Reperfusion in Diabetic Retinopathy Following Treatment With anti-VEGF Intravitreal InjectionsAzizan HakimAinda não há avaliações

- MataDocumento16 páginasMataIslah NadilaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Pone 0131770 PDFDocumento23 páginasJournal Pone 0131770 PDFKarina Mega WAinda não há avaliações

- Case Vignette in NCM 116B (E/E-Age Related Macular Degeneration)Documento4 páginasCase Vignette in NCM 116B (E/E-Age Related Macular Degeneration)faye kimAinda não há avaliações

- 2020 - 10.1007 - s00347 020 01250 yDocumento10 páginas2020 - 10.1007 - s00347 020 01250 yEko NoviantiAinda não há avaliações

- Retinopathy of Prematurity: GGW Adams Moorfields Eye Hospital, LondonDocumento29 páginasRetinopathy of Prematurity: GGW Adams Moorfields Eye Hospital, LondonJuan R. AntunezAinda não há avaliações

- Cyclosporine Cationic Emulsion Pediatric VKDocumento11 páginasCyclosporine Cationic Emulsion Pediatric VKDinda Ajeng AninditaAinda não há avaliações

- Retina Clinica Trials Update - 0813 - Supp2Documento16 páginasRetina Clinica Trials Update - 0813 - Supp2cmirceaAinda não há avaliações

- Anti-VEGF Agents and Their Clinical Applications: Dr. Sriniwas Atal MD. Resident OphthalmologyDocumento67 páginasAnti-VEGF Agents and Their Clinical Applications: Dr. Sriniwas Atal MD. Resident OphthalmologySriniwasAinda não há avaliações

- Original Investigation: JamaDocumento13 páginasOriginal Investigation: JamaGema Akbar WakhidanaAinda não há avaliações

- Opth 9 367Documento5 páginasOpth 9 367titisAinda não há avaliações

- Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus - EyeWikiDocumento1 páginaHerpes Zoster Ophthalmicus - EyeWikiStephanie AureliaAinda não há avaliações

- Recovery Following The TransplantDocumento10 páginasRecovery Following The TransplantAci Indah KusumawardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO) : How Does BRVO Occur?Documento3 páginasBranch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO) : How Does BRVO Occur?merizAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 2: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3No EverandClinical Management Review 2023-2024: Volume 2: USMLE Step 3 and COMLEX-USA Level 3Ainda não há avaliações

- tmp5D2D TMPDocumento4 páginastmp5D2D TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Uveitis: Signs and SymptomsDocumento4 páginasUveitis: Signs and SymptomsMoses Karanja Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- KP LamafIS Sin1Documento1 páginaKP LamafIS Sin1Indra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Mata36a PDFDocumento10 páginasMata36a PDFIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Mata PonkoppDocumento7 páginasJurnal Mata PonkoppIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Eye Journal PonkopDocumento7 páginasEye Journal PonkopIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal ObgynDocumento10 páginasJurnal ObgynIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Initial Resus TableDocumento3 páginasInitial Resus TableParama AdhikresnaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal LL LL PediatriDocumento4 páginasJournal LL LL PediatriIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

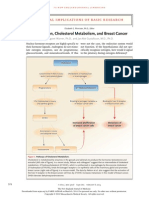

- CholesterolDocumento2 páginasCholesterolIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Metodologi Penelitian Kedokteran Dan Kesehatan Kedokteran Dan KesehatanDocumento16 páginasMetodologi Penelitian Kedokteran Dan Kesehatan Kedokteran Dan KesehatanGhisqy Arsy MulkiAinda não há avaliações

- Daftar PusTaka SNHDocumento7 páginasDaftar PusTaka SNHIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Cover Kel. A19 Respi FixxDocumento1 páginaCover Kel. A19 Respi FixxIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Penggunaan Berbagai Cut-Off Indeks Massa Tubuh Sebagai Indikator Obesitas Terkait Penyakit Degeneratif Di IndonesiaDocumento14 páginasPenggunaan Berbagai Cut-Off Indeks Massa Tubuh Sebagai Indikator Obesitas Terkait Penyakit Degeneratif Di IndonesiaLutfi RensiansiAinda não há avaliações

- Abnormal Breath SoundsDocumento3 páginasAbnormal Breath SoundsIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Abnormal Breath SoundsDocumento3 páginasAbnormal Breath SoundsIndra PermanaAinda não há avaliações

- Ministry of Truth Big Brother Watch 290123Documento106 páginasMinistry of Truth Big Brother Watch 290123Valentin ChirilaAinda não há avaliações

- E 18 - 02 - Rte4ltay PDFDocumento16 páginasE 18 - 02 - Rte4ltay PDFvinoth kumar SanthanamAinda não há avaliações

- WWW - Ib.academy: Study GuideDocumento122 páginasWWW - Ib.academy: Study GuideHendrikEspinozaLoyola100% (2)

- Unsaturated Polyester Resins: Influence of The Styrene Concentration On The Miscibility and Mechanical PropertiesDocumento5 páginasUnsaturated Polyester Resins: Influence of The Styrene Concentration On The Miscibility and Mechanical PropertiesMamoon ShahidAinda não há avaliações

- Improving Self-Esteem - 08 - Developing Balanced Core BeliefsDocumento12 páginasImproving Self-Esteem - 08 - Developing Balanced Core BeliefsJag KaleyAinda não há avaliações

- Water On Mars PDFDocumento35 páginasWater On Mars PDFAlonso GarcíaAinda não há avaliações

- CV AmosDocumento4 páginasCV Amoscharity busoloAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 2-ED (Theory)Documento13 páginasUnit 2-ED (Theory)chakramuAinda não há avaliações

- Strategi Pencegahan Kecelakaan Di PT VALE Indonesia Presentation To FPP Workshop - APKPI - 12102019Documento35 páginasStrategi Pencegahan Kecelakaan Di PT VALE Indonesia Presentation To FPP Workshop - APKPI - 12102019Eko Maulia MahardikaAinda não há avaliações

- Direct Filter Synthesis Rhea PreviewDocumento25 páginasDirect Filter Synthesis Rhea Previewoprakash9291Ainda não há avaliações

- Quarter 2-Module 7 Social and Political Stratification: Department of Education Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento21 páginasQuarter 2-Module 7 Social and Political Stratification: Department of Education Republic of The Philippinestricia100% (5)

- Class NotesDocumento16 páginasClass NotesAdam AnwarAinda não há avaliações

- AS 1 Pretest TOS S.Y. 2018-2019Documento2 páginasAS 1 Pretest TOS S.Y. 2018-2019Whilmark Tican MucaAinda não há avaliações

- Rizal ExaminationDocumento3 páginasRizal ExaminationBea ChristineAinda não há avaliações

- (Durt, - Christoph - Fuchs, - Thomas - Tewes, - Christian) Embodiment, Enaction, and Culture PDFDocumento451 páginas(Durt, - Christoph - Fuchs, - Thomas - Tewes, - Christian) Embodiment, Enaction, and Culture PDFnlf2205100% (3)

- Mathematics - Grade 9 - First QuarterDocumento9 páginasMathematics - Grade 9 - First QuarterSanty Enril Belardo Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Commercial CrimesDocumento3 páginasCommercial CrimesHo Wen HuiAinda não há avaliações

- Aìgas of Bhakti. at The End of The Last Chapter Uddhava Inquired AboutDocumento28 páginasAìgas of Bhakti. at The End of The Last Chapter Uddhava Inquired AboutDāmodar DasAinda não há avaliações

- 38 Page 2046 2159 PDFDocumento114 páginas38 Page 2046 2159 PDFAkansha SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Tool Stack Template 2013Documento15 páginasTool Stack Template 2013strganeshkumarAinda não há avaliações

- Creating Literacy Instruction For All Students ResourceDocumento25 páginasCreating Literacy Instruction For All Students ResourceNicole RickettsAinda não há avaliações

- Biblehub Com Commentaries Matthew 3 17 HTMDocumento21 páginasBiblehub Com Commentaries Matthew 3 17 HTMSorin TrimbitasAinda não há avaliações

- TLS FinalDocumento69 páginasTLS FinalGrace Arthur100% (1)

- Introduction To Sociology ProjectDocumento2 páginasIntroduction To Sociology Projectapi-590915498Ainda não há avaliações

- Elementary SurveyingDocumento19 páginasElementary SurveyingJefferson EscobidoAinda não há avaliações

- Stroke Practice GuidelineDocumento274 páginasStroke Practice GuidelineCamila HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Software Project Management PDFDocumento125 páginasSoftware Project Management PDFUmirAinda não há avaliações

- Aroma TherapyDocumento89 páginasAroma TherapyHemanth Kumar G0% (1)

- Financial Crisis Among UTHM StudentsDocumento7 páginasFinancial Crisis Among UTHM StudentsPravin PeriasamyAinda não há avaliações

- Gothic Revival ArchitectureDocumento19 páginasGothic Revival ArchitectureAlexandra Maria NeaguAinda não há avaliações