Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Untitled

Enviado por

api-193771047Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Untitled

Enviado por

api-193771047Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Psychosomatic Research

Psychosocial predictors of irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and

symptom severity

Kristy Phillips, Bradley J. Wright, Stephen Kent

School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 14 April 2013

Received in revised form 1 August 2013

Accepted 2 August 2013

Keywords:

Alexithymia

Coping

Early life experiences

Emotional processing

Maladaptive schemas

Psychological distress

a b s t r a c t

Objective: This study explored the role of psychosocial factors in predicting both membership to either an irritable

bowel syndrome (IBS) or control group, and the severity of IBS symptoms.

Methods: A total of 149 participants (82 IBS and 67 controls) completed a battery of self-report inventories

assessing disposition and environment, cognitive processes, and psychological distress. Logistic regression analyses were used to assess predictive contribution of psychosocial variables to IBS diagnosis. Hierarchical linear regression was then used to assess the relationship of psychosocial variables with the severity of IBS symptoms.

Results: Signicant predictors of IBS were found to be alexithymia, the defectiveness/shame schema, and four coping

dimensions (active coping, instrumental support, self-blame, and positive reframing), 2 (6, N = 130) = 46.99,

p b .001, with predictive accuracy of 72%. Signicant predictors of IBS symptom severity were two of the

alexithymia subscales (difculty identifying feelings, and difculty describing feelings), gender, the schemas of

defectiveness/shame and entitlement, and global psychological distress. This model predicted IBS severity

F (6, 64) = 16.94, p b .001 and accounted for 61.3% of the variability in IBS severity scores.

Conclusion: Psychosocial variables account for a large percentage of the differences between an IBS and control group, as well as the variance of symptoms experienced within the IBS group. Alexithymia and the defectiveness schema appear to be related to both IBS and symptom severity.

2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID). Characteristically IBS presents with intestinal problems including abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and constipation, with

additional symptoms of bloating, gas, swelling, and urgency [1]. Currently, no identiable structural abnormality, biological marker, or specic bacterial imbalance has been identied to explain these symptoms

[2]. IBS is diagnosed in around 10% of the general population and up to

25% in Western countries, making it the most common cause of referral

to a gastroenterologist [3,4]. Presently, the Rome III criteria is the most

comprehensive diagnostic tool for IBS; specifying that an individual experience abdominal pain, or discomfort for at least 3 days per month for

a 3 month period. These symptoms must be accompanied with two of

the following: changes in stool frequency (more or less), or form

(harder or looser), or the discomfort is relieved with defecation [5]. Patients' symptomology can appear medically unexplainable, meaning a

diagnosis is often accompanied with feelings of misunderstanding and

stigmatisation [6], which potentially reduces help-seeking behaviours

[7].

Corresponding author at: School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University,

Bundoora, VIC 3086, Australia. Tel.: +61 3 9479 2798; fax: +61 3 9479 1956.

E-mail address: s.kent@latrobe.edu.au (S. Kent).

0022-3999/$ see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.08.002

IBS signicantly impacts on an individual's quality of life and

wellbeing in areas including diet, travel, physical appearance, work,

family, education, and normal physical and sexual relationships [8,9].

In addition, IBS presents a burden to the health care system through

costs associated with primary-care doctors, gastroenterologists, hospital admissions, and prescription of pharmaceuticals [10].

Research into a biopsychosocial model for IBS [11] has identied a

number of psychosocial factors that strongly inuence IBS in three main

pathways: mediating the function and sensation of the gut, specically

inuencing the presenting symptom type and severity of pain reported;

causing certain illness behaviours; and lastly, mediating the risk of

onset, due to stress or trauma. Psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive

and behavioural, psychosocial, and long-term interpersonal psychotherapy) have been found to help IBS sufferers improve not only in psychopathology, social functioning, and quality of life, but also in gastrointestinal

symptoms and pain [1013] independent of psychological distress

[14,15]. However, the mechanisms relating to the efcacy of psychological treatments in IBS remain relatively unclear [15,16]. It is possible that

psychological interventions may help to address deeper issues not yet

understood.

Unlike short-term cognitive therapy that primarily focuses on two

levels of thoughts (automatic thoughts and underlying assumptions),

schema-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) addresses what

is believed to be the deepest level of cognitions, early maladaptive

schemas. Schemas are understood as pervasive implicit themes that a

468

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

person holds about self, others, and the world; formed in early years as a

result of some ongoing dysfunction in childhood where core emotional

needs were unmet [17]. Schemas interfere with relationships and

boundaries, self-acceptance, and a person's ability to satisfy basic

needs. Schemas have been related to a number of pathologies including

substance use, personality disorders, eating disorders, depression, and

psychosomatic illnesses [1720]. However, to date no research has explored the potential role schemas may play in explaining IBS.

Comorbid with IBS is often varying degrees of emotional and psychological distress, with many reaching diagnostic criteria for mood

and anxiety disorders [2123]. A recent review found that 40% to 60%

of patients with FGID, most commonly IBS, met criteria for a comorbid

psychiatric diagnosis, compared with only 25% of patients with structural bowel diseases, and 20% of the general population [24]. No causal relationship has been established between psychopathology and IBS;

however, pre-existing psychological disorders have been associated

with increased severity of IBS symptoms [25]. Hypochondriasis,

somatisation, and dissociation have been identied in some IBS sufferers [7,23,2528], although no study has found a unique psychological

prole for IBS.

IBS has been associated with higher traits of neuroticism

(characterised by emotional instability) and introversion, and

lower levels of openness and agreeableness [29]. Several studies

have also found that a many IBS sufferers score high in the personality

trait alexithymia [3032]. Alexithymia is dened as dysfunction in affect regulation, relating to difculties identifying and distinguishing between feelings and the physiological sensations of arousal; difculty

describing feelings and identifying them in others; a constricted imagination; and an outward cognitive style. Alexithymia does not always

present as blunted affect, but can present as emotional outbursts

where the individual is unable to identify the feeling state or relate it

to situations, memories, or higher-order emotions [33]. Alexithymia in

FGID and specically IBS impacts on responsiveness to treatment after

controlling for baseline gastrointestinal symptoms [30,31] and is associated with increased symptom severity [34].

More generally, the degree to which people actively avoid or are

unable to express and process difcult or distressing emotions has

been related to different illness symptoms; increased tension, perceived pain symptoms, and psychosomatic illnesses [3537]. Emotional processing is a process in which emotional disturbances are

absorbed, so that following the disturbance subsiding, the individual is able to return to normal functioning. Objectively this involves

returning to routine behaviours with diminished distress, even

when presented with reminders of the emotional disturbance [38].

The psychological mechanisms underlying emotional processing

are believed to be related to modications in associative memory

structures [39]. Despite the link between emotional processing and

psychosomatic illness, to our knowledge it has not yet been investigated in an IBS population.

Environmental factors that cause considerable emotional distress,

such as chronic stress, trauma, and abuse have been linked to IBS and

the severity of symptoms [4042]. Even a person's ability to manage

day to day stressors can inuence health and well-being. Recent research suggests that IBS patients rely more heavily on passive and

emotion-focused coping strategies [4345]. There is limited information, however, explaining how these coping strategies relate to IBS

symptomology.

The overall aim of the present study was to gain a better understanding of the differences in psychosocial functioning within an IBS group,

and when compared to a healthy control group. Firstly, we planned to

explore and ascertain the differences between groups. Secondly, we

aimed to formulate a comprehensive psychosocial prole for IBS. Finally,

we aimed to develop a psychosocial prole relating the severity of IBS

symptoms. Three groups of psychosocial determinants were explored:

dispositional and environmental factors; cognitive processes; and

psychological distress. Dispositional and environmental factors are

important risk factors for IBS, while cognitive and psychological distress

factors provide avenues for clinical intervention. By exploring these factors in combination we can determine the unique contribution of each

towards explaining IBS, and differences in symptomology.

Method

Participants

Participants presented as two discrete groups: a diagnosed IBS group

and a control group, comprising of 149 participants (82 IBS and 67 controls). IBS participants were diagnosed prior to participation, with diagnoses from a doctor (n = 34), a gastroenterologist (n = 46), or another

health professional (n = 2); diagnoses duration ranged from 2 weeks

to 40 years. IBS participants reported their predominant symptom to

be diarrhoea (n = 28), constipation (n = 20), alternating between diarrhoea and constipation (n = 28), or pain/bloating (n = 6) (Table 1).

Both IBS and control participants were excluded if they had a current or

previous diagnosis of bowel disease (e.g., ulcerative colitis). Inclusion

criteria specied Australian residents 18 years and over.

Study measures

IBS Symptom Severity Score (IBS-SSS) [46], a simple 5-question

self-report assessment tool, measured the severity of symptoms in

participants with a diagnosis of IBS. Symptoms range from mild to

severe and the maximum score is 500. Diagnosis classications are:

mild (75 to b 175), moderate (175 to b300), and severe (N 300). Reliability for the IBS severity score for the current study was good

(Cronbach's = .64).

Dispositional and environmental variables

The standardised version of the Life Events Inventory (LEI) [47] was

used to measure the incidence of stressful events experienced in the

previous 12 months. Participants respond in the negative or afrmative

to a list of 55 events, each item having an assigned weighting score to

represent the severity of stress typically associated. The LEI is a useful

tool to quantify stress in epidemiological studies, and to investigate

the relationship between stressful life events and vulnerability to psychopathology and illness outcomes [48,49]. Reliability for the LEI was

good (Cronbach's = .71).

Alexithymia was assessed with the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia

Scale (TAS-20) [50]. The TAS-20 has a three-factor structure: difculty identifying feeling, difculty describing feelings, and externally

Table 1

Demographic characteristics

Gender (%)

Males (females)

Age, year M (SD)

Relationship (%)

In a relationship

Single

Employment status (%)

Employed

Not employed

Highest level of education (%)

Pre-university level

Undergraduate level

IBS diagnosis duration, year M (SD)

IBS currently on medication for symptoms (%)

Predominant IBS symptom (n)

Constipation/Diarrhoea/Alternating/Pain

IBS

participants

(n = 82)

Control

participants

(n = 67)

22 (78)

43.8 (16.5)

25 (75)

38.8 (14.2)

69.5

30.5

77.6

22.4

62.2

37.8

76.1

23.9

51.2

48.8

10.2 (10.6)

39

20/28/28/6

40.3

59.7

.627

.051

.265

.066

.186

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

orientated thinking. The reliability of the scale is well established

( = .76 to .87). Internal consistency in the present study was

good (Cronbach's = .86). The TAS-20 has been used with IBS and

other FGID populations [3032].

Cognitive variables

The Emotional Processing Scale (EPS-25) [51], a 25-item questionnaire, was used to explore individuals' emotional experience, emotional

processing, and control of emotions in the past week. It has good reliability ( = .89) and sound testretest reliability. Cronbach's in the

present study was .82 to .90. To our knowledge the current study is

the rst to use the EPS-25 specically with an IBS clinical population.

Emotional processing has been linked with numerous other physical

and psychological health indicators [3537,52,53].

The Young Schema Questionnaire Short Form (YSQ-S2) [54] was used

to explore participants' maladaptive schemas (i.e., dysfunctional pervasive ideas that an individual holds about themselves and others believed

to have been formed in childhood by failing to have core emotional needs

met) [55]. The self-report questionnaire assesses 15 maladaptive schemas

(emotional deprivation, abandonment, mistrust/abuse, social isolation,

defectiveness/shame, failure, dependence/incompetence, vulnerability

to harm/illness, enmeshment, subjugation, self-sacrice, emotional inhibition, unrelenting standards, entitlement, and insufcient self-control/

self-discipline). It has sound reliability and validity; Cronbach's in the

present study was .83 to .89. The YSQ is a modest predictor of psychopathology scores [20] and personality disorders [56]. To our knowledge this

scale has no history in IBS research.

The Brief COPE, a 28-item self-report inventory [57] assessed commonly used coping strategies. The scale yields fourteen subscales, comprised of two items each. Reliability for the scale has been established

(Cronbach's = .42 to .93; .39 to .89 in the present study).

Psychological distress variables

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [58] was used to assess psychological distress. This inventory has been standardised to differentiate healthy controls from psychiatric patients. Responses on a 5-point

Likert scale provide a global score of psychological distress, and scores on

9 major symptom dimensions: somatisation, obsessivecompulsive behaviour, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic

anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Psychometric properties

are good with testretest reliability ranging from = .78 to .90. In the

present study the Cronbach's ranged from .85 to .94. The SCL-90-R

has previously been used to assess psychological distress in IBS and

other FGID [59,60].

Procedure

Institutional ethics approval for this study was granted from the La

Trobe University Faculty of Science, Technology & Engineering Human

Ethics Committee. Following this, participants were recruited via print

advertisements distributed to IBS support services, local gastroenterologists, and around university campus. An online advertisement was also

placed with The Gut Foundation. Most participants completed the battery of self-reported questionnaires directly on-line, accessed remotely,

while a minority (n = 14), who were unable to access the internet,

were mailed out hard copies, that were later posted back to La Trobe.

All questionnaires were completed anonymously.

Statistical analysis

SPSS Windows Version 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used

for all statistical analyses. Missing value analysis was conducted. Normality was assessed using visual inspection of histograms and stem

and leaf plots. Skew and kurtosis were examined at an alpha level of

b.001 [61]. Natural logarithmic transformations were necessary for

the subscales of the LEI, the Brief COPE, and the SCL-90-R. Non-

469

parametric testing (MannWhitney U) was necessary for four of the

subscales of SCL-90-R, which remained skewed. Due to signicant

skew in the Brief COPE subscales of denial, substance use, and religion,

these variables were omitted from the analysis. In order to normalise

the YSQ-S2 each variable was dichotomized. Following transformations,

group differences were explored using parametric (student t-tests) and

non-parametric (chi-square analysis and Mann-Whitney U) analyses.

An alpha level of .05 was used unless otherwise specied by the

Bonferroni adjustments. A logistic regression analysis was conducted

using a forward solution to predict group membership (IBS versus control) from predictor variables. Removal of 8 multivariate outliers was

necessary based on leverage and standardised residuals. A stepwise hierarchical linear regression analysis was then performed creating a predictive model for severity of symptoms in the IBS group. Six participants

were excluded from the analysis due to missing data and 5 outliers were

removed based on leverage, covariance ratios, and standardised residuals. All statistical procedures were devised a priori to assess our specic

research questions.

Results

Descriptive statistics

A MANOVA revealed no signicant multivariate F (5,149) = 1.75, p = .127, or

univariate differences in demographic characteristics for the IBS and control groups

using the Bonferroni correction (.05/5 = .01) (Table 1). Mean current symptoms

(over the previous 10 days) for the IBS group were reported to be moderately severe

(M = 261.9, SD = 98.5). One-way ANOVA determined a main effect due to symptom

type (constipation, diarrhoea, and alternating) F (3, 77) = 3.29, p = .025. Post hoc

analyses found that there was no signicant difference between the groups in symptom severity.

Psychosocial differences between IBS and control group

Signicant differences were detected for total alexithymia and two subscales of

alexithymia (difculty identifying feelings and externally orientated thinking), emotional

processing, instrumental support coping, somatisation, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, phobic anxiety, psychoticism, and global psychological distress (Table 2). Due to

multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni adjusted alpha levels apply to the COPE variables

(.05/11 = .004), LEI variables (.05/2 = .025), TAS-20 variables (.05/4 = .0125), and

the SCL-90-R variables (.05/10 = .005). Phi describes the correlation between two discrete variables, and as such the values range from 0 to 1, with Cohen suggesting that .1,

.3, and .5 correspond with small, medium, and large effects. Cohen's d effects of .2, .5,

and .8, also correspond to small, medium, and large effects [62].

Between-group differences for maladaptive schemas were determined by chi-square

analyses. A signicant group difference was identied for the emotional inhibition schema

(Table 3). Due to multiple comparisons the Bonferroni adjusted alpha levels were used

(.05/15 = .003).

Predicting IBS or control group membership

A forward-step logistic regression was performed in order to determine the signicant

predictors of IBS and control group membership (Table 4). Disposition and environmental

factors (age, gender, relationship status, education, total alexithymia, and alexithymia subscales, and exposure to signicant life events) were scrutinised rst as these factors are

considered stable risk factors. Cognitive factors (coping strategies, maladaptive schemas,

and emotional processing) were compared next. Lastly psychological distress variables

were compared. Six signicant predictors were identied in the forward regression,

which were then entered into a hierarchical logistic regression.

A test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically signicant, indicating that 6 of the predictors as a set reliably distinguished between the IBS and a control group, 2 (6, N = 130) = 46.99, p b .001. According to Cox and Snell R2 and

Nagelkerke R2 between 30% and 41% of the variability in scores between the IBS group

and the control group is explained by this set of variables. Overall, the model correctly

categorised 72% of participants as IBS or control (64% for controls and 79% for the IBS

group).

The Wald criterion demonstrated that all 6 predictors made statistically signicant

contributions. Odds ratios indicated that a person reporting IBS was 10 times higher for

each 1 unit increase in active coping, 6.5 times higher for a 1 unit increase in the maladaptive schema defectiveness/shame, and 5 times higher for a 1 unit increase in instrumental

support coping.

Predicting the severity of IBS symptoms

A linear regression using a forward-step solution was used to isolate the most significant variables that predicted IBS symptom severity. The variables that remained were

470

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

Table 2

Mean group differences for alexithymia, life events, coping strategies, emotional processing, and psychological distress

Scales

LEI

LEI

TAS-20

TAS-F1

TAS-F2

TAS-F3

EPS-25

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

COPE

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R

Subscale predictor variables

Severity of life events

Frequency of life events

Total alexithymia

Difculty identifying feelings

Difculty describing feelings

Externally-orientated thinking

Total emotional processing

Self-distraction

Active coping

Emotional support

Instrumental support

Behaviour. disengagement

Venting

Positive reframing

Planning

Humour

Acceptance

Self-blame

Somatisation

Obsessivecompulsive

Interpersonal sensitivity

Depression

Anxiety

Hostility a

Phobic anxiety a

Paranoid ideation

Psychoticism a

Global psych distress a

IBS

Control

SD

SD

1.68

1.68

50.8

17.78

13.17

19.87

3.74

1.61

1.85

1.64

1.37

1.53

1.54

1.81

1.45

1.84

1.71

1.48

0.64

0.70

0.63

0.73

0.51

0.50

0.29

0.47

0.30

0.73

0.68

0.68

12.5

6.91

4.51

4.74

1.88

0.35

0.31

0.34

0.32

0.32

0.36

0.31

0.35

0.31

0.36

0.37

0.34

0.43

0.43

0.43

0.40

0.170.83

0.000.71

0.42

0.100.90

0.341.24

1.61

1.60

43.4

14.51

11.58

17.35

3.09

1.56

1.70

1.58

1.27

1.46

1.63

1.69

1.48

1.70

1.53

1.48

0.44

0.54

0.45

0.53

0.39

0.33

0.00

0.32

0.20

0.39

0.59

0.59

12.2

6.91

4.51

4.26

1.73

0.36

0.36

0.35

0.28

0.30

0.37

0.37

0.37

0.36

0.36

0.35

0.29

0.36

0.34

0.36

0.36

0.170.50

0.000.14

0.31

0.000.50

0.230.73

0.73

0.73

3.57

2.83

2.11

3.31

2.15

0.91

2.60

0.90

2.92

2.05

1.52

1.41

2.18

0.45

2.46

0.11

3.82

2.42

2.89

2.97

1.87

1.99

3.71

2.41

3.20

3.23

.464

.464

b.001

.005

.037

.001

.034

.365

.010

.368

.004

.043

.130

.162

.031

.584

.015

.914

b.001

.017

.005

.004

.063

.047

b.001

.017

.001

.001

0.11

0.13

0.60

0.47

0.35

0.56

0.36

0.14

0.45

0.17

0.33

0.23

0.25

0.35

0.08

0.42

0.50

0.00

0.63

0.40

0.46

0.50

0.32

0.41

The sample size differs from the total sample of participants due to missing data across subscales. Control participants n ranged from 64 to 67; IBS n ranged from 78 to 82.

a

Indicates that the variable is non-normally distributed as such non-parametric testing of MannWhitney U has been performed with descriptive statistics of median and interquartile

ranges reported, and Z-scores.

entered into a hierarchical regression. Disposition and environmental factors (age, gender,

relationship status, education, total alexithymia, and alexithymia subscales: difculty

identifying feelings, difculty describing feelings, and externally-orientated thinking,

and exposure to signicant life events) were scrutinised rst as these factors are considered stable risk factors. Cognitive factors (coping strategies, maladaptive schemas, and

emotional processing) were compared next. Lastly psychological distress variables were

compared. Six signicant predictors were identied in the forward-step regression,

which were then entered into a hierarchical linear regression. A statistically signicant

change was detected at each step of the model (Table 5).

The full model signicantly predicted IBS severity F (6, 64) = 16.94, p b .001 and

accounted for 61.3% of the variability in IBS severity scores. Two of the alexithymia subscales (difculty identifying feelings, and difculty describing feelings) and gender

explained approximately 38.5% of the variance in IBS severity. Maladaptive schemas of

defectiveness/shame, and entitlement explained 14% of the variance, and global psychological distress explained a further 8.5% of the variance.

Discussion

The results of the current study illustrate important psychosocial differences between the IBS group and the control group. Psychosocial factors can signicantly predict, within this group, whether a person has a

diagnosis of IBS or not. Further, psychosocial factors also predict the

subjective severity of IBS symptoms experienced.

Table 3

Group differences for cognitive schemas (YSQ-S2)

Maladaptive

IBS (n = 72)

Schemas

Response f

Response f

Endorsing Schema

Endorsing Schema

Emotional deprivation

Abandonment

Mistrust/abuse

Social isolation

Defectiveness/shame

Failure

Dependence

Vulnerable to harm/illness

Enmeshment

Subjugation

Self-sacrice

Emotional inhibition

Unrelenting standards

Entitlement

Insufcient self-control

Control (n = 61)

Yes

No

Yes

No

31

14

16

24

14

13

14

18

9

16

30

20

51

21

17

41

58

56

48

58

59

58

54

63

56

42

52

21

51

55

15

4

6

10

3

4

8

7

4

6

24

4

41

18

11

46

57

55

51

58

57

53

54

57

55

37

57

20

43

50

Phi

4.98

4.69

3.67

4.98

6.25

3.92

0.96

3.96

1.32

3.67

0.074

10.01

0.20

0.002

0.62

.026

.030

.055

.026

.012

.048

.328

.047

.250

.055

.786

.002

.652

.966

.432

0.19

0.19

0.17

0.19

0.22

0.17

0.09

0.17

0.10

0.17

0.02

0.28

0.04

0.01

0.07

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

471

Table 4

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis of the contributions of disposition/environment, cognitive, and psychological distress in predicting IBS or control group membership

95% condence interval

for odds ratio

Predictors

Disposition/environment

Alexithymia

Cognitive/coping

COPEactive coping

COPEinstrumental support

COPEself blame

COPEpositive reframing

YSQdefectiveness/shame

SE

Wald 2 test

df

0.64

0.21

9.64

.002

1.07

1.02

1.11

2.31

1.61

2.31

2.09

1.87

0.87

0.69

0.77

0.75

0.82

7.14

5.43

8.94

7.73

5.14

1

1

1

1

1

.008

.020

.003

.005

.023

10.09

5.01

0.10

0.12

6.48

1.85

1.29

0.02

0.03

1.29

54.98

19.43

0.45

0.54

32.53

Comparisons between IBS and controls

Several studies to date have investigated the psychological and social

differences between controls and individuals suffering from IBS. However, to our knowledge this is the rst study to investigate the dimensions

of emotional processing and maladaptive schemas in IBS. It is also, to our

understanding, the rst to look at psychosocial predictors of both categorical classication, and dimensional symptom severity. This in-depth

approach informs our understanding of how psychological interventions

can assist with varying presentations of this disorder. Consistent with

previous research [25,30,44,60,63], differences between the IBS and the

control groups were observed in psychological (i.e., somatisation, depression, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism and global psychological distress),

social (i.e., help seeking through instrumental support, and interpersonal

sensitivity), and emotional (alexithymia, emotional inhibition, and emotional processing) domains. Based on both signicant p values and medium effect sizes the most important group differences appear to exist on

the subscales of psychological distress (Cohen's d ranged from .35

to.60), total alexithymia (Cohen's d = .60), two alexithymia subscales;

externally orientated thinking (Cohen's d = .56) and difculty identifying feelings (Cohen's d = .47), and the emotional inhibition schema

(Phi = .28) [62].

One of our primary objectives was to develop a comprehensive psychosocial prole for IBS. A number of predictors were explored using a

regression model to distinguish between the two groups. Six predictors

were found to independently predict group membership to either the

IBS or control group; in combination they explained 30% to 41% of the

variance between the groups, correctly classifying 72% of the participants. Predictors of IBS included disposition (alexithymia) and cognitive

strategies (defectiveness/shame schema, seeking instrumental social

support, and active coping). Predictors of membership to the healthy

control group were cognitive strategies (positive reframing and selfblame). The most important discriminator was active coping with a

person scoring high in active coping being 10 times more likely to belong to the IBS group.

Table 5

Hierarchical linear regression depicting the contributions of dispositional/environmental,

cognitive, and psychological distress factors on IBS symptom severity (IBS-SSS)

Predictors

Final

summary

Beta

Step 1

TAS-20 difculty identifying feelings

TAS-20 difculty describing feelings

Gender

Step 2

YSQ entitlement

YSQ defectiveness/shame

Step 3

SCL-90R global psychological distress

Dependent variable: IBS-SSS.

Step

summary

r

sr

.238

.370

.153

.232

.510

.004

.149

.167

.318

.261

.069

.497

.344

.231

.053

.474

.643

.293

R2 ch

.384

b.001

.143

b.001

.086

b.001

Odds ratio

Lower

Upper

Several studies have reported a link between alexithymia and IBS in

both diagnosis and responsiveness to treatment [3032,34,64]. In the

present study one-fth of the IBS group's scores indicated that they

were highly alexithymic, however, on average the IBS group were within

the borderline alexithymic classication [32]. The control group differed

signicantly from the IBS group with a medium effect size (Cohen's

d = .6); reporting mean scores indicative of low alexithymia, also termed

non-alexithymic. In reecting on these ndings it is important to note

that alexithymia is not unique to IBS. Alexithymia has been reliably linked

to physical illness including chronic pain, and physical trauma (i.e., rape

and burn victims) [65,66]. Although alexithymia appears to be a relatively

stable and enduring personality trait in the general population [67], some

research has found that it emerged in individuals following a physical illness, and similarly decreased following illness resolution [66,68]. Due to

the cross-sectional nature of this study it is not possible to determine if

alexithymia is an antecedent to IBS, or a response. However, a common

thread that appears present in both alexithymia [69,70] and IBS [71,72]

is somatosensory amplication. Alexithymia may play a role in altering

and intensifying perception of physical sensations commonly found in

IBS, leading to health care seeking and subsequent diagnosis [2,7375].

This relationship requires further exploration.

Maladaptive schemas, which form a template of how we relate to

ourselves and others, are believed to be pervasive and enduring, having

origins in early childhood life experiences [55]. As this is the rst study

to explore schemas in IBS, these ndings suggest that the schema of defectiveness/shame formed prior to a diagnosis of IBS. People with this

schema may see themselves as innately awed and fear rejection. It

has been suggested that this schema may develop from a home environment that is detached and critical; where needs for stability, nurturance,

and empathy are unmet [55]. One study [76] found that parenting style

(particularly one that is rejecting and hostile) was a stronger predictor

of IBS somatic complaints, than specic abuse experiences. Our ndings

offer further evidence that negative parenting and family environments

are related to IBS, comparatively we found no relationship with reported stressful life experiences. It appears that substandard parentalchild

interactions may create vulnerabilities that impede psychological functioning and normal stress responses [76,77].

A further nding from the present study was that actively seeking

social support to cope with stresses predicted membership to the IBS

group. Despite a link between IBS and vulnerability to social isolation

[78], our ndings may potentially reect the fact that a large proportion

of participants were recruited from support groups and this may confound interpretation. Social support in IBS has been related to a reduction in pain symptomology by way of lowering stress levels [79].

Despite the identied group differences in reports of psychological distress (as measured by the SCL-90-R), psychological distress factors were

not found to signicantly contribute to a diagnosis of IBS.

Predictors of IBS symptom severity

The secondary objective of our investigation was to determine

which factors were predictive of IBS symptom severity, with an aim of

472

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

identifying predictors of severe symptomology. Despite recent increased interest in IBS severity subtypes (mild, moderate, and severe),

especially as an outcome measure for clinical intervention, to date

there has been limited research into the psychological predictors of

symptom severity [79,80]. The current research utilised the IBS-SSS to

assess IBS symptoms on a number of dimensions including, pain (both

severity and duration), distension (bloating and abdominal tightness),

satisfaction with bowel habits, and overall impact of symptoms on quality of life. A comprehensive psychosocial prole utilising dispositional,

cognitive, and psychological distress factors was determined to distinguish between IBS symptom severity. Six factors signicantly predicted

IBS symptom severity: two alexithymia subscales (difculty identifying

feelings and difculty describing feelings), gender, the maladaptive

schemas of entitlement and defectiveness/shame, and global psychological distress. In combination these factors accounted for 61.3% of

the variance in severity of symptoms.

Gender was found to signicantly predict IBS severity, with females

more likely to report severe symptomology. This could be indicative of

an unequal gender split; however, previous research into IBS has identied gender differences in brain activation and sensory amplication

to visceral stimulation [8183]. These ndings suggest possible different

gender-specic cognitive pathways involved in the processing of symptoms [82,83]. Psychological distress was also found to be a signicant

predictor of IBS symptom severity; consistent with previous research

[63,80]. As we did not assess for pre-existing psychopathology, it is

not possible to distinguish whether psychological distress inuenced

the severity of symptoms reported, or if the distress was a result of managing severe symptomology. However, gender and psychological distress appear to be the variables most related to IBS severity, with both

factors uniquely explaining 32% and 29% of the variance respectively.

Alexithymia predicted IBS group membership; however, it was the

subscales related to identifying and describing emotions that predicted

the severity of symptoms. It has been suggested that individuals high

in alexithymia have an impaired ability to identify and process emotions, including identifying stress or negative emotions [84], which is associated with reduced activation of the anterior cingulate cortex, a

critical region in cognitive and emotional processing [85]. The stress

alexithymia hypothesis suggests that in the presence of stressful life

events alexithymia prevents appropriate coping mechanisms [65]. Consequently, individuals may fail to act in a timely manner to reduce or

manage stress, or they may respond in unhealthy ways that prolong exposure to stress. The compounding impacts of stress may lead to somatosensory amplication, where somatic and visceral sensations are

experienced as more intense and unpleasant [84] as seen in severe IBS.

To our knowledge the relationship between maladaptive schemas

and IBS symptom severity has not previously been investigated. Along

with predicting a diagnosis of IBS, the schema of defectiveness/shame

also predicted the severity of symptoms experienced. The entitlement

schema also predicted symptom severity. Underlying this schema is believed to be a fragility that is related to emotional deprivation. People

with this schema may long for emotional intimacy, but fear it because

of a belief that they are defective, and consequently push others away.

They may believe that exposing aws will result in rejection [55], likely

leading to physical and emotional isolation. These ndings highlight the

importance of exploring early life experiences in IBS, and the long-term

implication for symptom exacerbation. As suggested earlier, adaption to

a hostile, or emotionally invalidating early home environment may result in profound cognitive and physiological changes [75]. Maladaptive

schemas have been found to play a role in addiction, personality disorders, and psychopathology [20,54,55], however only limited research

has been conducted into the relationship with medical illnesses [85],

and this should be an avenue for future research.

Although this study took a comprehensive approach to IBS there are

notable limitations. All data was self-reported including participants' diagnosis of IBS; therefore it is unclear if a common diagnostic measure

was used (such as the Rome III criteria). However, participants were

only accepted into the study if they reported that a formal diagnosis

had been provided by a health professional. While we report no differences between groups in their demographics (Table 1), we did not assess either group on dimensions of physical health, aside from IBS and

IBD; hence we cannot be certain that there are no other differences in

health status separating the groups. Another limitation was the data collection method; completion of questionnaires took place in the home,

university, or work environment, and hence we cannot discount that socially desirable responding, biased responses. A further limitation is that

the life event inventory only explored events in the past 12 months, yet

our participants' diagnosis ranged from 2 weeks to 40 years. While the

sample population may impact on the generalizability of the ndings, it

did not impact on the power of the study, with signicant ndings attributed to very large effect sizes. Finally, while we used the Bonferroni

adjustment for each cluster of related variables, we did not adjust for all

variables considered together; as such readers are advised to refer to

both p values and effect sizes when interpreting ndings.

In conclusion, meaningful differences were identied between the

IBS and control group on a number of environmental, cognitive, and

psychological distress factors, further supporting the role of psychosocial factors in IBS [11]. We determined the most important elements

that inuenced both diagnosis of IBS, and the severity of those symptoms. Our ndings suggest that IBS has a strong emotional component.

We found in both diagnosis and severity of symptoms there was a relationship with invalidating emotional experiences, as well as difculties

with emotional expression and recognition. Our ndings allude to the

importance of early life experiences in possibly creating a psychological

and physiological vulnerability to IBS and the severity of symptoms.

These ndings offer further support for the importance of psychological

interventions, most specically CBT and schema-focused CBT to assist

with core issues relating to IBS. Previous research has found that CBT

can directly improve quality of life and gastrointestinal symptoms in

IBS independent to addressing any psychological distress [15]. Although

we identied that psychological distress was predictive of increased

symptomology, other psychological aspects evidently play an inuential

role in IBS and its severity. CBT is currently the most effective psychological intervention for alexithymia [86,87], and CBT addresses maladaptive or inaccurate thoughts, beliefs, and behaviours, which often

maintain maladaptive schemas. IBS is not a uniform diagnosis; there

are important psychosocial variances. We have provided a rationale

for the value of thorough psychosocial assessment and therapeutic interventions targeted at individual symptom proles.

Conict of interest

All authors declare no conicts of interest in relation to the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants and thank the Irritable Bowel Information and Support (IBIS) group, Gut Foundation, and Gastro North

for their invaluable assistance in advertising and recruiting for this research study. We are also grateful to Dr. Ben Ong, of La Trobe University,

for his support regarding statistical analysis.

All authors had access to all the data in the study and have been

involved in the drafting and revisions of this paper, and provided approval for the nal version of this paper to be published. The corresponding author takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy

of the data.

This study has been funded by La Trobe University, Melbourne.

However, the university had no role in the collection, management,

analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation of this

manuscript.

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

References

[1] Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating

IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes,

CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inamm Bowel Dis 2007;14:329.

[2] Rutter CL, Rutter DL. Illness representation, coping and outcome in irritable bowel

syndrome (IBS). Br J Health Psychol 2002;7:37791.

[3] Clarke G, Quigley EMM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Irritable bowel syndrome: towards biomarker identication. Trends Mol Med 2009;15:47887.

[4] Jones R, Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. Br

Med J 1992;304:8790.

[5] Gwee K. Irritable bowel syndrome and the Rome III criteria: for better or for worse?

Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:4379.

[6] Crane C, Martin M. Perceived vulnerability to illness in individuals with irritable

bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:111522.

[7] Trikas P, Vlachonkolis I, Fragkiadakis N, Vasilakis S, Manousos O, Paritsis N. Core

mental state in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med 1999;61:7818.

[8] Whitehead W, Burnett CK, Cook EW, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on

quality of life. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:224853.

[9] Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin I. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:64350.

[10] Ljotsson B, Andreewitch S, Hedman E, Ruck C, Andersson G, Lindefors N. Exposure

and mindfulness based therapy for irritable bowel syndrome an open pilot

study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2010;41:18090.

[11] Lackner JM, Mesmer C, Morley S, Dowzer C, Hamilton S. Psychological treatments for

irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin

Psychol 2004;72:110013.

[12] Craske ]MG, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Labus J, Wu S, Frese M, Mayer E, et al.

A cognitive-behavioral treatment for irritable bowel syndrome using interoceptive

exposure to visceral sensations. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2011;49:41321.

[13] Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Palsson O, Faurot K, Mann JD, Whitehead WE. Therapeutic

mechanisms of a mindfulness-based treatment for IBS: effects on visceral sensitivity,

catastrophizing, and affective processing of pain sensations. Journal of Behavioral

Medicine 2012;35(6):591602.

[14] Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B, et al. Does psychological treatment help only those patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome who also have a concurrent psychiatric disorder? Australian and New

Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2005;39(9):80715. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/pubmed/16168039.

[15] Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Blanchard EB. How does cognitive behavior therapy for IBS work?: a mediational analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology 2007;133:43344.

[16] Naliboff BD, Frese MP, Rapgay L. Mind/body psychological treatments for irritable

bowel syndrome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2008;5:4150.

[17] Salkovskis PM. Frontiers of cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1996 .

[18] Ball SA. Manualized treatment for substance abusers with personality disorders:

dual focus schema therapy. Addict Behav 1998;22:88391.

[19] Leung N, Waller G, Thomas G. Outcome of group cognitive-behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa: the role of core belief. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:14556.

[20] Stopa L, Thorne P, Waters A, Preston J. Are the short and long forms of the young

schema questionnaire comparable and how well does each version predict psychopathology scores? J Cogn Psychother 2001;15:25361.

[21] Mykletun A, Jacka F, Williams L, Pasco J, Henry M, Nicholson GC, et al. Prevalence of

mood and anxiety disorder in self-reported irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). An epidemiological population based study of women. Br Med J Gastroenterol 2010;10:

8897.

[22] Roy-Byrne PP, Davidson KW, Kessler RC, Asmundson GJG, Goodwin RD, Kubzansky

L, et al. Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. J Lifeline Learn Psychiatry

2008;1:46781.

[23] Sykes MA, Blanchard EB, Lackner J, Keefer L, Krasner S. Psychopathology in irritable

bowel syndrome: support for a psychophysiological model. J Behav Med 2003;26:

36171.

[24] Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology

2006;130:144758.

[25] Gwee KA, Leong YL, Graham C, McKendrick MW, Collins SM, Walters SJ, et al. The

role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut

1999;44:4006.

[26] Alim MA, Hussain AM, Haque MA, Ahad MA, Islam QT, Ekram ARMS. Assessment of

psychiatric disorders in irritable bowel syndrome patients. The Journal of Teachers

Association 2005;18:103.

[27] Salmon P, Skaife K, Rhodes J. Abuse, dissociation and somatisation in irritable bowel

syndrome: towards and explanatory model. J Behav Med 2003;26:118.

[28] Wilhelmsen I. The role of psychosocial factors in gastrointestinal disorders. Gut

2000;47:735.

[29] Dinan TG, O'Keane V, O'Boyle C, Chua A, Keeling PWN. A comparison of the mental

status, personality proles and life events of patients with irritable bowel syndrome

and peptic ulcer disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991;84:268.

[30] Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Baldassarre G, Altomare DF, Palasciano G. Pan-enteric

dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients

meeting ROME II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol

2003;9:22939.

[31] Porcelli P, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, De Carne M, Leandro G, Todarello O. Alexithymia as

predictor of treatment outcome in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine 2003;65:9118.

473

[32] Porcelli P, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, De Carne M. Alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal

disorders: a comparison with inammatory bowel disease. Psychother Psychosom

1999;68:2639.

[33] Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997 .

[34] Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S, Machida T, Machida T, Noda S, et al. The features of adolescent irritable bowel syndrome in Japan. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

2011;26:1069.

[35] Keefe FJ, Lumley J, Anderson T, Lynch T, Carson KL. Pain and emotion. J Clin Psychol

2001;57:587607.

[36] Brosschot JF, Aarsse HR. Restricted emotional processing and somatic attribution in

bromyalgia. Int J Psychiatry Med 2001;31:12746.

[37] Walter S, Leissner N, Jerg-Bretzke L, Hrabal V, Traue HC. Pain and emotional processing in psychological trauma. Psychiatr Danub 2010;22:46570.

[38] Rachman S. Emotional processing. Behav Res Ther 1980;18:5160.

[39] Foa E, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information.

Psychol Bull 1986;99:2035.

[40] Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, Badcock CA, Kellow JE. Level of chronic life stress

predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1998;43:25661.

[41] Blanchard E B, Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Rowell D, Carosella AM, Powell C, et al. The role

of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:

11928.

[42] Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007;8:33143.

[43] Goodhand J, Rampton D. Psychological stress and coping in IBD. Gut 2008;57:

13457.

[44] Jones MP, Weissinger S, Crowel MD. Coping strategies and interpersonal support in

patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inammatory bowel disease. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;4:47481.

[45] Pelissier S, Dantzer C, Canini F, Mathieu N, Bonaz B. Psychological adjustment and

autonomic disturbances in inammatory bowel diseases and irritable bowel syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010;35:65362.

[46] Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:395402.

[47] Spurgeon A, Jackson CA, Beach JR. The life events inventory: re-scaling based on an

occupational sample. J Occup Med 2001;51:28793.

[48] Enns ME, Cox BJ. Perfectionism, stressful life events, and the 1-year outcome of depression. Cogn Ther Res 2005;29:54153.

[49] Lillberg K, Verkasalo PK, Kaprio J, Teppo L, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M. Stressful life

events and risk of breast cancer in 10,808 women: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol

2003;157:41523.

[50] Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale I: item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res 1994;38:2332.

[51] Baker R, Thomas S, Thomas PW, Gower P, Santonastaso M, Whittleasea A. The emotional processing scale: scale renement and abridgement (EPS-25). J Psychosom

Res 2010;68:838.

[52] Baker R, Holloway J, Thomas PW, Thomas S, Owens M. Emotional processing and

panic. Behav Res Ther 2004;42:127187.

[53] Rachman S. Emotional processing, with special reference to post traumatic stress

disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry 2001;13:16471.

[54] Young JE, Brown G. Young schema questionnaire (revised ed.). In: Young JE, editor.

Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: a schema-focused approach. 2nd ed.

New York: Cognitive Therapy Center; 1994. p. 6376.

[55] Young JE, Klosko J, Weishaar ME. Schema therapy: a practitioner's guide. New York:

Guilford Press; 2003 .

[56] Reeves M, Taylor J. Specic relationships between core beliefs and personality

disorder symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Clin Psychol Psychother 2007;14:

96104.

[57] Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically

based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;56:26783.

[58] Derogatis LI. The SCL-90-R administration, scoring, and procedures manual. 3rd

ed.Minneapolis: National Computer Systems, Inc.; 1994.

[59] Drossman DA. Do psychosocial factors dene symptom severity and patient status in

irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Med 1999;107:41S50S.

[60] Locke GR, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested casecontrol study.

Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:3507.

[61] Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed.Boston: Pearson Education Inc.; 2007.

[62] Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:1559.

[63] Jarrett M, Heitkemper M, Cain KC, Tuftin M, Walker EA, Bond EF, et al. The relationship between psychological distress and gastrointestinal symptoms in women with

irritable bowel syndrome. Nurs Res 1998;47:15461.

[64] Arun P. Alexithymia in irritable bowel syndrome. Indian J Psychiatry 1998;40:7983.

[65] Martin JB, Pihl RO. The stress alexithymia hypothesis: theoretical and empirical considerations. Psychother Psychosom 1985;43:16976.

[66] Wise TN, Mann LS, Mitchell D, Hryvniak M, Hill B. Secondary alexithymia: an empirical validation. Compr Psychiatry 1990;31:2848.

[67] Saarijaervi S, Salminen JK, Toikka T. Temporal stability of alexithymia over a

ve-year period in outpatients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom

2006;75:10712.

[68] Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Concept of alexithymia: II. The consistency of alexithymia.

Psychother Psychosom 1987;47:11320.

[69] Wise TN, Mann LS. The relationship between somatosensory amplication,

alexithymia, and neuroticism. J Psychosom Res 1994;38:51521.

474

K. Phillips et al. / Journal of Psychosomatic Research 75 (2013) 467474

[70] Lumley MA, Strettner L, Wehmer F. How are alexithymia and physical illness

linked: a review and critique of pathways. J Psychosom Res 1996;41:

50518.

[71] Duddu V, Isaac MK, Chaturvedi SK. Somatization, somatosensory amplication,

attribution styles and illness behaviour: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006;18:

2533.

[72] Chang L. Brain responses to visceral and somatic stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome:

a central nervous system disorder? Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:27180.

[73] Porcelli P, Affatati V, Bellomo A, De Carne M, Todarello O, Taylor GJ. Alexithymia and

psychopathology in patients with psychiatric and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychother Psychosom 2004;73:8491.

[74] Wilhelmsen I. Biological sensitisation and psychological amplication: gateways to

subjective health complaints and somatoform disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology

2005;30:9905.

[75] Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Blanchard EB. Beyond abuse: the association among parenting

style, abdominal pain, and somatization in IBS patients. Behav Res Ther 2004;42:4156.

[76] Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the

mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 2002;128:23066.

[77] Porcelli P. Psychological abnormalities in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Indian J Gastroenterol 2004;23:639.

[78] Bertram S, Kurland M, Locke GR, Lydick E, Yawn BP. The patient's perspective of irritable bowel syndrome. J Fam Pract 2001;50:5217.

[79] Lackner JM, Brasel AM, Quigley BM, Keefer L, Krasner SS, Powell C, et al. The ties

that bind: perceived social support, stress, and IBS in severely affected patients.

Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:893900.

[80] Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, Mayer EA, Chang L. Predictors of patient-assessed

illness severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:253643.

[81] Lee OY, Mayer EA, Schmulson M, Chang L, Naliboff B. Gender-related differences in

IBS symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:218493.

[82] Naliboff BD, Berman S, Chang L, Derbyshire SW, Suyenobu B, Vogt BA, et al.

Sex-related differences in IBS patients: central processing of visceral stimuli. Gastroenterology 2003;124:173847.

[83] Berman S, Munakata J, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Mandelkern M, Silverman D, et al.

Gender differences in regional brain response to visceral pressure in IBS patients. Eur J Pain 2000;4:15772.

[84] Kano M, Fukudo S. The alexithymic brain: the neural pathways linking alexithymia

to physical disorders. Biopsychosoc Med 2013;7:19.

[85] Mizara A, Papadopoulos L, McBride SR. Core beliefs and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis and atopic eczema attending secondary care: the role of

schemas in chronic skin disease. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:98693.

[86] Bermond B, Vorst HC, Moormann PP. Cognitive neuropsychology of alexithymia: implications for personality typology. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2006;11:33260.

[87] Kojima M. Alexithymia as a prognostic risk factor for health problems: a brief review

of epidemiological studies. Biopsychosoc Med 2012;6:19.

Você também pode gostar

- Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Caregivers of Patients With Chronic DiseasesDocumento8 páginasPrevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Caregivers of Patients With Chronic Diseasesapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Physicians' Awareness and Patients' ExperienceDocumento6 páginasIrritable Bowel Syndrome: Physicians' Awareness and Patients' Experienceapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Partner Burden in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: See Editorial On Page 156Documento5 páginasPartner Burden in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: See Editorial On Page 156api-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Anxiety-Depressive Disorders Among Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients in Guilan, IranDocumento7 páginasAnxiety-Depressive Disorders Among Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients in Guilan, Iranapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Anxiety, Stress, & Coping: An International JournalDocumento17 páginasAnxiety, Stress, & Coping: An International Journalapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Health Effects of Expressive Letter Writing: Mosher and Danoff-BurgDocumento19 páginasHealth Effects of Expressive Letter Writing: Mosher and Danoff-Burgapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Behaviour Research and TherapyDocumento9 páginasBehaviour Research and Therapyapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Healing Words: Using Affect Labeling To Reduce The Effects of Unpleasant Cues On Symptom Reporting in IBS PatientsDocumento9 páginasHealing Words: Using Affect Labeling To Reduce The Effects of Unpleasant Cues On Symptom Reporting in IBS Patientsapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Health Psychology Review: Click For UpdatesDocumento25 páginasHealth Psychology Review: Click For Updatesapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Original Papers: The Lifetime Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders Among Patients With Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocumento6 páginasOriginal Papers: The Lifetime Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders Among Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndromeapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Autonomic Effects of Expressive Writing in Individuals With Elevated Blood PressureDocumento13 páginasAutonomic Effects of Expressive Writing in Individuals With Elevated Blood Pressureapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Illness Perceptions Mediate The Relationship Between Bowel Symptom Severity and Health-Related Quality of Life in IBS PatientsDocumento12 páginasIllness Perceptions Mediate The Relationship Between Bowel Symptom Severity and Health-Related Quality of Life in IBS Patientsapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Does Expressive Writing Reduce Stress and Improve Health For Family Caregivers of Older Adults?Documento11 páginasDoes Expressive Writing Reduce Stress and Improve Health For Family Caregivers of Older Adults?api-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Feature: Biofeedback and Expressive Writing: Emotional Disclosure and Its Effects On HealthDocumento6 páginasFeature: Biofeedback and Expressive Writing: Emotional Disclosure and Its Effects On Healthapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- In Search of Attachment: A Qualitative Study of Chronically Ill Women Transitioning Between Family Physicians in Rural Ontario, CanadaDocumento12 páginasIn Search of Attachment: A Qualitative Study of Chronically Ill Women Transitioning Between Family Physicians in Rural Ontario, Canadaapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Learning About Oneself Through Others: Experiences of A Group-Based Patient Education Programme About Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocumento10 páginasLearning About Oneself Through Others: Experiences of A Group-Based Patient Education Programme About Irritable Bowel Syndromeapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- Psychodynamic Interpersonal Therapy and Improvement in Interpersonal Difficulties in People With Severe Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocumento8 páginasPsychodynamic Interpersonal Therapy and Improvement in Interpersonal Difficulties in People With Severe Irritable Bowel Syndromeapi-193771047Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- ISBDFinal Book 2012 BDocumento53 páginasISBDFinal Book 2012 BvadamadaAinda não há avaliações

- The NysseDocumento208 páginasThe NysseSiti Nur JariyahAinda não há avaliações

- C1 Ob-Gyn-2020Documento33 páginasC1 Ob-Gyn-2020yabsera mulatuAinda não há avaliações

- Mentha Cordifelia TeaDocumento10 páginasMentha Cordifelia TeaMia Pearl Tabios ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Icpc 2 R PDFDocumento204 páginasIcpc 2 R PDFagni sukma fahiraAinda não há avaliações

- 0-0013 PDFDocumento24 páginas0-0013 PDFisabellaprie3Ainda não há avaliações

- Sample Only - Not For Clinical UseDocumento6 páginasSample Only - Not For Clinical Usenostra83Ainda não há avaliações

- CV - Microbiology Infection ControlDocumento14 páginasCV - Microbiology Infection ControlDrRahul KambleAinda não há avaliações

- Evedenced Based Rectal ProlapseDocumento16 páginasEvedenced Based Rectal Prolapsesub_zero9909Ainda não há avaliações

- II-E Altered PerceptionDocumento16 páginasII-E Altered PerceptionDharylle CariñoAinda não há avaliações

- Icmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (These Fields To Be Filled For All Patients Including Foreigners)Documento2 páginasIcmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (These Fields To Be Filled For All Patients Including Foreigners)Recruitment Cell Aiims BilaspurAinda não há avaliações

- Pap SmearDocumento75 páginasPap SmearRaine BowAinda não há avaliações

- Geriatric NursingDocumento64 páginasGeriatric NursingMark Elben100% (2)

- Takayasu S Arter It IsDocumento5 páginasTakayasu S Arter It IsButarbutar MelvaAinda não há avaliações

- Cholinergic SyndromeDocumento3 páginasCholinergic SyndromeEmman AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- (2020) (Libro) Health Psychology - The BasicsDocumento267 páginas(2020) (Libro) Health Psychology - The BasicsERIKA REYES GOMEZAinda não há avaliações

- 11 - Precautions For Handling Organic SolventDocumento2 páginas11 - Precautions For Handling Organic SolventMummy TheAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Ernst Ziegler-1stEd PDFDocumento392 páginasDr. Ernst Ziegler-1stEd PDFcasAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Minute Exam DFSDocumento2 páginas3 Minute Exam DFSWeeChuan NgAinda não há avaliações

- Buildings and Structures: Padua EsteDocumento2 páginasBuildings and Structures: Padua EsteKevin LavinaAinda não há avaliações

- 1-Disease MechanismsDocumento5 páginas1-Disease MechanismsMarian Dane PunzalanAinda não há avaliações

- Clonazepam Drug CardDocumento1 páginaClonazepam Drug CardSheri490Ainda não há avaliações

- Sarcoidosis Pathophysiology, Diagnosis AtfDocumento6 páginasSarcoidosis Pathophysiology, Diagnosis AtfpatriciaAinda não há avaliações

- Chest Physician in Pune - Dr. Sharadchandra YadavDocumento8 páginasChest Physician in Pune - Dr. Sharadchandra YadavSharad YadavAinda não há avaliações

- Classical Western FormulasDocumento4 páginasClassical Western FormulasSofia MirandaAinda não há avaliações

- RANZCPdepression 2Documento120 páginasRANZCPdepression 2Random_EggAinda não há avaliações

- CASE PRESENTATION NEPHROTIC Syndrome-1Documento20 páginasCASE PRESENTATION NEPHROTIC Syndrome-1rohankananiAinda não há avaliações

- 2.1 NCM 109 - Pregestational ConditionsDocumento6 páginas2.1 NCM 109 - Pregestational ConditionsSittie Haneen TabaraAinda não há avaliações

- Panadeine: What Is in This LeafletDocumento3 páginasPanadeine: What Is in This Leafletradzi66Ainda não há avaliações

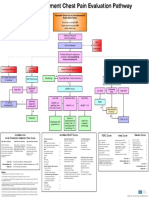

- Emergency Department Chest Pain Evaluation PathwayDocumento2 páginasEmergency Department Chest Pain Evaluation Pathwaymuhammad sajidAinda não há avaliações