Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Br. J. Anaesth. 2001 Cherian 502 4

Enviado por

Alief M. ZarendraDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Br. J. Anaesth. 2001 Cherian 502 4

Enviado por

Alief M. ZarendraDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

British Journal of Anaesthesia 87 (3): 5024 (2001)

Prophylactic ondansetron does not improve patient satisfaction in

women using PCA after Caesarean section

V. T. Cherian1 and I. Smith2*

1

Department of Anaesthesia, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore 632 004, India and

Department of Anaesthesia, North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire ST4 6QG, UK

*Corresponding author

Eighty-one consenting women undergoing elective Caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia

were randomly divided into two groups. In Group O patients, ondansetron 4 mg was given

intravenously at the end of the surgery and 8 mg added to the morphine solution in the PCA

syringe. Patients in Group P received only morphine via PCA syringe. Analgesia and nausea

were measured until PCA was discontinued 24 h after the operation. Women in the two

groups were similar with respect to age, duration of use of the PCA, amount of morphine

used, previous history of PONV, and incidence of motion sickness and morning sickness during

the current pregnancy. The number of women who complained of nausea and those needing

rescue antiemetic medication was signicantly less in Group O. However, there was no statistically signicant difference between the two groups in the patient's perception of the control

of nausea and their overall satisfaction. It was noted that PONV was more frequent among

women who had signicant morning sickness during early pregnancy and ondansetron was

benecial in reducing PONV in these women. Although the ondansetron reduced the incidence

of PONV and the need for further antiemetic medication, this did not affect patient's satisfaction regarding their postoperative care.

Br J Anaesth 2001; 87: 5024

Keywords: vomiting, nausea, postoperative; analgesia, patient-controlled; vomiting,

antiemetics, ondansetron; anaesthesia, obstetric

Accepted for publication: March 15, 2001

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with i.v. opioids provides effective postoperative analgesia, but may be limited

by nausea and vomiting (PONV). Adding droperidol

(0.050.2 mg ml1) to morphine in the PCA syringe reduces

the incidence of PONV,16 but is associated with increased

sedation and extrapyramidal side effects. Ondansetron, a

5HT3 receptor antagonist, may be preferable in the

postpartum period because it lacks sedative effects that

may delay bonding with the baby. Although most studies on

ondansetron have shown that it reduces the incidence of

PONV, some workers regard this as only a `surrogate'

endpoint.7 8 Few investigators have examined the patient's

satisfaction with their treatment of PONV, which may be

regarded as the more important outcome.7 8

The aim of our study was to evaluate whether administering prophylactic ondansetron along with morphine via

PCA decreased PONV in obstetric patients and patient

satisfaction.

Methods and results

This double-blind, placebo-controlled study was approved by the local research ethics committee. Eightyone women undergoing elective Caesarean section at

term under spinal subarachnoid block were selected and

gave written informed consent. The sample had 80%

power to detect a halving of PONV from our baseline

value of 60%, found in an earlier audit. Patients with

hepatic, renal, psychiatric or neurological diseases and

those with pre-eclampsia were excluded. History of

PONV, motion sickness, smoking, and morning sickness

were noted. Subarachnoid anaesthesia was administered

using 2.52.8 ml of hyperbaric 0.5% bupivacaine,

through a 25-G pencil-point needle. All patients received

co-amoxyclav 1.2 g and oxytocin 10 units i.v. after the

baby was delivered and diclofenac 100 mg p.r. at the

end of the operation.

The Board of Management and Trustees of the British Journal of Anaesthesia 2001

Prophylactic ondansetron in women using PCA after Caesarean section

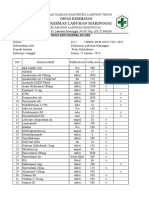

Table 1 Severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting and patient satisfaction with their control of nausea and vomiting and their overall level of care in the

two treatment groups. Values represent the most severe score recorded in the postoperative period (during PCA use) and are number (%) of occurrences or

responses

Nausea and vomiting (none/mild/severe/vomited)

Patients with morning sickness (n=52):

No PONV

Any PONV

Patients without morning sickness (n=29):

No PONV

Any PONV

Control of nausea and vomiting:

Good

Moderate

Poor

Overall satisfaction with care:

Good

Moderate

Poor

Group P (n=40)

Group O (n=41)

P value

15/2/5/18

26 / 5 / 3 / 7

7 (26%)

20 (74%)

16 (64%)

9 (36%)

0.023

0.005

8 (62%)

5 (38%)

10 (63%)

6 (37%)

24 (60%)

10 (25%)

6 (15%)

30 (73%)

9 (22%)

2 (5%)

35 (87.5%)

4 (10%)

1 (2.5%)

35 (85%)

5 (12%)

1 (3%)

Women were randomly allocated into two groups by

computer-generated random numbers in sequentially-numbered envelopes. Group P received a PCA with morphine (1

mg ml1), while Group O received ondansetron 4 mg

intravenously at the end of surgery plus 8 mg added to the

PCA morphine syringe (60 ml) (nal ondansetron concentration 0.13 mg ml1). The PCA pump was programmed to

deliver 1 ml per demand with a 3 min lockout and no

background infusion. Prochlorperazine 12.5 mg i.m. was

available as a rescue antiemetic to any patient who

requested it.

The incidence and severity of pain, sedation, nausea and

vomiting were assessed using four-point scales at 15 min

intervals in the immediate recovery period and then 4 hourly

until the PCA pump was discontinued. A midwife, unaware

of the contents of the PCA syringe, made all postoperative

assessments. Twenty-four hours later, one of the investigators assessed the patient for her perception regarding overall

satisfaction with her care, control of nausea and vomiting

and analgesia, using a scale of good, moderate or poor.

Data were analysed using the StatView statistical

package. Discrete variables were analysed using an

unpaired t-test or non-parametric tests. Categorical variables were analysed using the chi squared or Fisher's exact

test, as appropriate. In all cases a P value of <0.05 was

considered signicant.

Patient characteristics between the two groups were

similar except that the women in Group O were slightly

heavier. There were no signicant differences in the amount

of morphine used, history of motion sickness, morning

sickness, smoking, and PONV. The incidence of intraoperative hypotension and the requirement for an infusion

of oxytocin to assist postoperative uterine contraction did

not differ between the groups. There were no differences in

the degree of pain between the two treatment groups at any

time. Most patients were either pain-free or had only mild

pain. All patients were awake or arousable to voice at all

times.

0.960

0.258

0.9525

The incidence of nausea and vomiting was signicantly

lower in the ondansetron group (Table 1). Twenty-three

(57%) patients in Group P experienced severe nausea or

vomiting compared with 10 (24%) in Group O (P<0.01).

Eighteen women from Group P needed rescue antiemetic,

compared with only ve from Group O (P<0.01).

Ondansetron was effective in reducing the incidence of

PONV in those patients who had previously experienced

morning sickness but not in those who had not (Table 1).

There was no differential efcacy of ondansetron in patients

with and without previous PONV, smoking or motion

sickness, although the number of patients with these risk

factors was relatively small. Six patients in Group P and two

in Group O felt that the control of nausea and vomiting was

`poor', the difference was not signicant. One patient in

each group felt their overall care was unsatisfactory

(Table 1).

Comment

In post-Caesarean section patients, we found that adding

ondansetron to morphine in the PCA syringe reduces the

incidence of PONV and the requirement for antiemetic

rescue without increasing sedation. However, it seemed to

make little difference to the patient's perception of the

control of their nausea or her feeling of satisfaction with the

overall quality of care. This is consistent with other workers

who reported that reducing the incidence of PONV did not

improve patient satisfaction.9

There are various factors that may contribute to PONV.10

The most important predictors are female gender, previous

PONV, prolonged surgery, non-smoking, and motion sickness.10 We found that the incidence of PONV was higher

among women who had signicant morning sickness during

early pregnancy. Ondansetron was benecial in reducing

PONV in these women, but appeared to make little

difference in patients who did not experience signicant

morning sickness.

503

Cherian and Smith

Prophylaxis of PONV is usually administered once or

intermittently. There are a few studies where the antiemetic

was added into the PCA syringe.16 Droperidol was used in

most of these and was found to be effective, but caused

increased sedation, a side effect that we felt was undesirable

in the postpartum period. Postoperative sedation was rare in

our patients and was not increased by the use of

ondansetron. Alexander and colleagues showed that a

bolus of ondansetron 4 mg plus 0.13 mg ml1 in the PCA

syringe was effective in reducing PONV after orthopaedic

surgery.2 This technique has not previously been investigated in postpartum patients.

When questioned about their perception of nausea and

overall care, the responses of the two groups were similar,

despite considerable differences in the incidence of PONV

and request for rescue antiemetics. The high level of

satisfaction could partly be a result of the euphoria of having

a newborn baby and to the extra attention given by a

sympathetic investigator who spent extra time with them.

However, this should have applied equally to both groups.

Ondansetron is safe and effective, with a low incidence of

adverse effects such as headache, dizziness, and increased

liver enzymes. It has also been shown to be compatible with

morphine sulphate.2 There are no reports of adverse effects

of ondansetron in women who are breast feeding, although

the manufacturer cautions against its use in this situation.

However, similar advice applies to droperidol and prochlorperazine.

References

Acknowledgement

This study was conducted at the North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-onTrent, and was not funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

504

1 Kaufmann MA, Rosow C, Schnieper P, Schneider M. Prophylactic

antiemetic therapy with patient-controlled analgesia: a doubleblind,

placebo-controlled

comparison

of

droperidol,

metoclopramide and tropisetron. Anesth Analg 1994; 78: 98894

2 Alexander R, Lovell AT, Seingry D, Jones RM. Comparison of

ondansetron and droperidol in reducing postoperative nausea

and vomiting associated with patient-controlled analgesia.

Anaesthesia 1995; 50: 10868

3 Russell D, Duncan LA, Frame WT, Higgins SP, Asbury AJ, Millar

K. Patient-controlled analgesia with morphine and droperidol

following caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Acta

Anaesthesiol Scand 1996; 40: 6005

4 Williams OA, Clarke FL, Harris RW, Smith P, Peacock JE.

Addition of droperidol to patient-controlled analgesia: effect on

nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia 1993; 48: 8814

5 Roberts CJ, Millar JM, Goat VA. The antiemetic effectiveness of

droperidol during morphine patient-controlled analgesia.

Anaesthesia 1995; 50: 55962

6 Walder AD, Aitkenhead AR. A comparison of droperidol and

cyclizine in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting

associated with patient-controlled analgesia. Anaesthesia 1995;

50: 6546

7 Fisher DM. `The big little problem' of postoperative nausea and

vomiting. Do we know the answer yet? (Editorial). Anesthesiology

1997; 87: 12713

8 Fisher DM. Surrogate outcomes: meaningful not! (Editorial).

Anesthesiology 1999; 90: 3556

9 Scuderi PE, James RL, Harris L, Mims GR, III. Antiemetic

prophylaxis does not improve outcomes after outpatient surgery

when compared to symptomatic treatment. Anesthesiology 1999;

90: 36071

10 Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its

etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology 1992; 77:

16284

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Upt Puskesmas Labuhan Maringgai: Dinas KesehatanDocumento7 páginasUpt Puskesmas Labuhan Maringgai: Dinas KesehatanAlief M. ZarendraAinda não há avaliações

- MedicalDocumento456 páginasMedicalSri Sakthi Sumanan100% (1)

- Pharm 355Documento3 páginasPharm 355Alief M. ZarendraAinda não há avaliações

- Koagulasi Dan Flokulasi PrinsipDocumento129 páginasKoagulasi Dan Flokulasi PrinsipAndreaHalim0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Digestive SystemDocumento27 páginasDigestive SystemLealyn Martin BaculoAinda não há avaliações

- Stigma and IddDocumento22 páginasStigma and Iddapi-676636026Ainda não há avaliações

- First Dispensary RegistrationDocumento2 páginasFirst Dispensary RegistrationWBURAinda não há avaliações

- Selection of Site For HousingDocumento4 páginasSelection of Site For HousingAyshwarya SureshAinda não há avaliações

- Woman Burned by Acid in Random Subway Attack Has 16th SurgeryDocumento1 páginaWoman Burned by Acid in Random Subway Attack Has 16th Surgeryed2870winAinda não há avaliações

- List of Shelters in The Lower Mainland, June 2007Documento2 páginasList of Shelters in The Lower Mainland, June 2007Union Gospel Mission100% (1)

- Looking Forward: Immigrant Contributions To The Golden State (2014)Documento2 páginasLooking Forward: Immigrant Contributions To The Golden State (2014)CALimmigrantAinda não há avaliações

- A Sample Hospital Business Plan Template - ProfitableVentureDocumento15 páginasA Sample Hospital Business Plan Template - ProfitableVentureMacmilan Trevor Jamu100% (1)

- Constipation - MRCEM SuccessDocumento5 páginasConstipation - MRCEM SuccessGazi Sareem Bakhtyar AlamAinda não há avaliações

- First - Aid Common Emergencies and Safety Practices in Outdoor ActivitiesDocumento14 páginasFirst - Aid Common Emergencies and Safety Practices in Outdoor ActivitiesJhon Keneth NamiasAinda não há avaliações

- Caravan Tourism in West BengalDocumento2 páginasCaravan Tourism in West BengalUddipan NathAinda não há avaliações

- Anaphylaxis - 2Documento8 páginasAnaphylaxis - 2Ronald WiradirnataAinda não há avaliações

- Mil PRF 680Documento14 páginasMil PRF 680Wisdom SamuelAinda não há avaliações

- Rimso 50Documento1 páginaRimso 50monloviAinda não há avaliações

- Ayahuasca GuideDocumento27 páginasAyahuasca GuidedevoutoccamistAinda não há avaliações

- Errors of Eye Refraction and HomoeopathyDocumento11 páginasErrors of Eye Refraction and HomoeopathyDr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD HomAinda não há avaliações

- Httpsjkbopee Gov InPdfDownloader Ashxnid 13580&type NDocumento221 páginasHttpsjkbopee Gov InPdfDownloader Ashxnid 13580&type NMONISAinda não há avaliações

- Britannia Industry LTD in India: Eat Healthy Think BetterDocumento12 páginasBritannia Industry LTD in India: Eat Healthy Think BetterMayank ParasharAinda não há avaliações

- Reimplantation of Avulsed Tooth - A Case StudyDocumento3 páginasReimplantation of Avulsed Tooth - A Case Studyrahul sharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Mental HealthDocumento80 páginasMental HealthSingYen QuickAinda não há avaliações

- The Trade Effluents (Prescribed Processes and Substances) Regulations 1992Documento2 páginasThe Trade Effluents (Prescribed Processes and Substances) Regulations 1992Lúcio FernandesAinda não há avaliações

- FAQ Mid Day MealsDocumento7 páginasFAQ Mid Day Mealsvikramhegde87Ainda não há avaliações

- Heat StrokeDocumento4 páginasHeat StrokeGerald YasonAinda não há avaliações

- A Case Study of Wastewater Reclamation and Reuse in Hebei Province in China: Feasibility Analysis and Advanced Treatment DiscussionDocumento2 páginasA Case Study of Wastewater Reclamation and Reuse in Hebei Province in China: Feasibility Analysis and Advanced Treatment DiscussionShalynn XieAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Digital Media On Sleep Pattern Disturbance in Medical and Nursing StudentsDocumento10 páginasImpact of Digital Media On Sleep Pattern Disturbance in Medical and Nursing StudentsValarmathiAinda não há avaliações

- GHGK SDocumento48 páginasGHGK SAnonymous Syr2mlAinda não há avaliações

- STCW Section A-Vi.1Documento6 páginasSTCW Section A-Vi.1Ernesto FariasAinda não há avaliações

- COVID-19: Vaccine Management SolutionDocumento7 páginasCOVID-19: Vaccine Management Solutionhussein99Ainda não há avaliações

- Lifeline Supreme BrochureDocumento5 páginasLifeline Supreme BrochureSumit BhandariAinda não há avaliações

- HR Director VPHR CHRO Employee Relations in San Diego CA Resume Milton GreenDocumento2 páginasHR Director VPHR CHRO Employee Relations in San Diego CA Resume Milton GreenMiltonGreenAinda não há avaliações