Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Equity Access Allocation Conflict in The Bhavani

Enviado por

shashvatarya0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

46 visualizações2 páginasCase Study

Título original

Equity Access Allocation Conflict in the Bhavani

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoCase Study

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

46 visualizações2 páginasEquity Access Allocation Conflict in The Bhavani

Enviado por

shashvataryaCase Study

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 2

EQUITY, ACCESS AND ALLOCATION

Conflict in the Bhavani

An increase in population, unplanned expansion in the command

area of the river Bhavani in Tamil Nadu and the growing domestic

and industrial demand for water have intensified competition

among water users in the river basin.

A RAJAGOPAL, N JAYAKUMAR

havani is an important tributary of

the Kaveri in its mid-reaches in

Tamil Nadu. It originates in the

Silent Valley forest in Kerala and flows

in a south-easterly direction for 217 km

till it joins the Kaveri at a town named

Bhavani. The total area of the Kaveri basin

in the state is about 43,000 km2 of which

the Bhavani sub-basin constitutes roughly

5,400 km2. The Kaveri basin which drains

Karnataka, Pondicherry, Kerala and Tamil

Nadu comprises about 82,000 km2 of which

the Bhavani river basin is 6,000 km2. A

major portion (87 per cent) of this area is

situated in Tamil Nadu.

The Lower Bhavani Project (LBP) is a

major multi-purpose reservoir, mainly

constructed for water storage and distribution to canal systems in the basin. The

reservoir is also used for hydel power

generation and fishing. Apart from this,

anicuts like Kodiveri and Kalingarayan

Economic and Political Weekly

are used to divert water into different canal

systems. These are old systems that have

been in existence for several centuries. The

upper part of the basin is not well developed and mostly depends upon wells and

rain-fed agriculture.

Parched Land, Thirsty People

The river plays an important role in the

economy of Coimbatore and Erode districts by providing water for drinking, agriculture and industry. Due to an increase

in population, unplanned expansion in the

command area, as well as the growing

domestic and industrial water demand, the

basin is already closing and stressed. As

a result there is intense competition among

water users and a sizeable gap exists

between demand and supply in agriculture

and domestic sectors.

Water shortage downstream is even

worse due to a prolonged drought that

has lasted several years. Out of about

February 18, 2006

1,700 mm3 of normal water supply in the

LBP dam the actual realisation declined

to 1,275 mm3 in 2001, 793 mm3 in 2002

and 368 mm3 in 2003. There was already

a conflict of interest between farmers in

the valley, the original settlers and the new

command farmers of LBP. Old command

farmers are entitled to 11 months water

supply which they used for growing two

or three paddy crops and annual crops like

sugar cane, banana, etc, whereas the new

ayacut farmers were only able to grow a

single paddy or dry crop in a year.

As long as water supply in the dam was

adequate the conflict too was subdued. But

supply was at an all time low in 2002 and

water was not released to the new command

area. This has prompted the new ayacutdars

to file a case against the state in the high

court seeking water supply for at least one

crop. Their contention is that water should

be provided for the second crop in the old

settlement only after meeting the requirements of the first crop in the new command

as per the Government Order (number

2,274)issued as early as August 30, 1963.

The court asked the Water Resources

Organisation to arrive at a compromise

formula for water sharing between the two

areas. The department prepared a plan on

the basis of size of command area 60 per

cent of the available water was to be given

to the new ayacut (for irrigation of 80,000

ha) and 40 per cent to the old ayacut (about

20,000 ha). However, the old settlers

objected on the grounds that they are

entitled to 11 months of interrupted water

supply as per their riparian rights. The

impasse prompted local central ministers

to bring the two sides to the negotiating

table but this attempt to seek a solution also

failed. The court in its interim order has

now told the state to take prior permission

from the court to open the system every

season. Under the original regulation the

canal was opened on April 18 for the old

settlement and August 15 for the new ayacut.

The expansion of irrigation and hence

demand has mostly taken place in upstream

areas (and to some extent in old ayacut too)

through unauthorised tapping of river water

by direct pumping. Apart from direct pumping the other major issue is the unregulated

exploitation of groundwater in the catchments, which the state is unable to control;

this practice is actually encouraged by

liberal institutional financing. Supply of

free electricity by the state has also contributed to the growth of this problem.

Downstream farmers did take the issue to

court and even won a favourable judgment

581

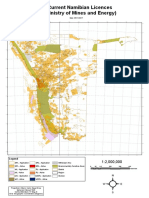

Figure: Bhavani Basin with Major Irrigation Canals

River

Irrigation Canal

City/Village

but the ineffective bureaucracy has been

unable to implement the courts orders.

Highs and Lows

Water conflicts played a major role in

the 14th general elections held in 2004.

There was a flurry of negotiations between politicians and farmers associations

in the basin.

The water-sharing problem between

the old and new settlers had been compounded by growing demand from

industry and the domestic sector. The

drought in 2004 had added to the situation

and there was a severe shortage of water

in the dam. As election time approached,

the ruling party ministers sought to build

up their vote banks by trying to get the

farmers to compromise; the effort failed

and in the meanwhile, the drought worsened and a new dimension was added to

the dispute. The water shortage in the region

forced the farmers in the Kaveri delta to

clamour for water. This group constitutes

a sizeable electorate and since it was

potentially more beneficial for the ruling

party to get their support, water from the

dam was released to the Kaveri delta, totally

against the norms set for operating the

reservoir. This angered the Bhavani basin

farmers who chose to nominate an independent candidate. They named him,

Water Candidate and this was a first in

the electoral history of India. However this

attempt too failed due to ideological differences among various agrarian groups

and finally it was a candidate from the

main opposition party in the state who won

the farmers vote.

This has helped the new command farmers to take up water issues with the irrigation bureaucracy and receive more water

from the reservoir easily as the politician

went on to become a minister in the central

government. The new command farmers

582

association has also taken the old settlers

to court with help from the minister.

While the case is now pending in court,

the water situation remains grim and the

domestic water consumers especially the

middle class have resorted to purchasing

water for drinking purposes. Farmers

affected by pollution have sought legal

remedies and have succeeded in getting

some of the polluting textile and chemical

units shut down. These are the spontaneous

actions of different stakeholders, with each

group working in isolation to resolve the

issue. Unfortunately it seems that farmers

have more faith in the legal system than

in other efforts.

The basin water management situation

is precarious due to uncoordinated action and counteraction by various

stakeholders. The situation is likely to

get critical in future as the demand from

the non-agricultural sector continues to

grow rapidly. Under these circumstances,

there is a need for an integrated approach

and a mechanism for coordinated development of water resources in the basin

with the participation of all those concerned, especially the state. This could be

undertaken by an external agency who

needs to get all parties farmers, industrialists, domestic users and the state

together and establish a forum where

solutions are sought through dialogue.

Gyan Ads

Stakeholders Dialogue Meeting

A stakeholders meeting was held

on February 21, 2005, to get ideas and

feedback from farmers, NGOs, government departments, industrialists, social

activists and academicians. All of them

have agreed to discuss these issues further

and negotiate their way out of the tough

situation. -29

Email: rajagopal@saciwaters.org

Economic and Political Weekly

February 18, 2006

Você também pode gostar

- Water Crisis in Pakistan QDocumento10 páginasWater Crisis in Pakistan Qmshoaib10126Ainda não há avaliações

- Presentation On Water Issues in PakistanDocumento15 páginasPresentation On Water Issues in PakistanEnviro_Pak0% (4)

- India Water StressDocumento6 páginasIndia Water StressSWYAM MEHROTRAAinda não há avaliações

- Final ReportDocumento5 páginasFinal Reportismail abibAinda não há avaliações

- Karnataka State Water PolicyDocumento12 páginasKarnataka State Water Policyseetha ramAinda não há avaliações

- Consti Moot Problem-1Documento4 páginasConsti Moot Problem-1Sanskruti AwareAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation Water Resource 1442680525 77894Documento22 páginasPresentation Water Resource 1442680525 77894Bomber3818 AAinda não há avaliações

- 14 94 PBDocumento12 páginas14 94 PBAbdullah Munir NourozAinda não há avaliações

- Readings 20 B HydropliticsDocumento18 páginasReadings 20 B HydropliticsHaider AliAinda não há avaliações

- Afghan Water ConflictDocumento11 páginasAfghan Water ConflictIbrahim BajwaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Scarcity: Myth or RealityDocumento8 páginasWater Scarcity: Myth or RealityMuhammad SaeedAinda não há avaliações

- Hydro Politics in Pakistan: Perceptions and MisperceptionsDocumento17 páginasHydro Politics in Pakistan: Perceptions and Misperceptionspak watanAinda não há avaliações

- Water Infrastructure and Water Allocation in California: Richard Howitt and Dave SundingDocumento10 páginasWater Infrastructure and Water Allocation in California: Richard Howitt and Dave SundingRomina CordovaAinda não há avaliações

- Maitra 2006 - Interstate Water Disputes in India Institutions and MechanismsDocumento23 páginasMaitra 2006 - Interstate Water Disputes in India Institutions and MechanismsDschingis KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Ensuring Drinking Water Study in GujaratDocumento46 páginasEnsuring Drinking Water Study in GujaratJoshi DhvanitAinda não há avaliações

- Providing Water Solutions for Jangugaon VillageDocumento3 páginasProviding Water Solutions for Jangugaon VillagePriyam MrigAinda não há avaliações

- Rally for Rivers MovementDocumento6 páginasRally for Rivers MovementGUNA KALYANAinda não há avaliações

- Hydro Politics in Pakistan: Understanding Perceptions and MisperceptionsDocumento18 páginasHydro Politics in Pakistan: Understanding Perceptions and MisperceptionsIqraAinda não há avaliações

- Groundwater Prospecting: Tools, Techniques and TrainingNo EverandGroundwater Prospecting: Tools, Techniques and TrainingAinda não há avaliações

- Columbia Basin Water Transactions Program: Annual Privatization Report 2004Documento2 páginasColumbia Basin Water Transactions Program: Annual Privatization Report 2004reasonorgAinda não há avaliações

- Water Crisis, Impacts and Management in PakistanDocumento4 páginasWater Crisis, Impacts and Management in PakistanMuhammad AliAinda não há avaliações

- Kalabagh Dam Technical Report Highlights Flaws in FeasibilityDocumento9 páginasKalabagh Dam Technical Report Highlights Flaws in FeasibilityTahir YousafzaiAinda não há avaliações

- 666666Documento34 páginas666666matijciogeraldineAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges of Natural Resources 176....Documento5 páginasChallenges of Natural Resources 176....faizaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Crisis in-WPS OfficeDocumento6 páginasWater Crisis in-WPS OfficeFayyaz Ahmad AnjumAinda não há avaliações

- The Ambitious Idea of River Interlinking: Good or Bad?Documento5 páginasThe Ambitious Idea of River Interlinking: Good or Bad?admAinda não há avaliações

- Enjoying This Article? Click Here To Subscribe For Full Access. Just $5 A MonthDocumento26 páginasEnjoying This Article? Click Here To Subscribe For Full Access. Just $5 A MonthBilal AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- English PPT (Venkat)Documento10 páginasEnglish PPT (Venkat)nadimetlavenkatAinda não há avaliações

- Water CrisisDocumento8 páginasWater CrisisDCM MianwaliAinda não há avaliações

- Water Resource Development Project: An Opportunity For Public-Private PartnershipDocumento10 páginasWater Resource Development Project: An Opportunity For Public-Private PartnershipJohn R. FleckAinda não há avaliações

- Water Scarcity in Pakistan: Causes, Effects and SolutionsDocumento4 páginasWater Scarcity in Pakistan: Causes, Effects and Solutionssalmanyz6Ainda não há avaliações

- CH 2 Part 3 Dams NotesDocumento4 páginasCH 2 Part 3 Dams NotesyashvikaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Shortage NewDocumento16 páginasWater Shortage NewTanyusha DasAinda não há avaliações

- Water Crisis in PakistanDocumento4 páginasWater Crisis in PakistanFaisal Javed100% (1)

- RaghavDrolia 1350 EVSC1Documento7 páginasRaghavDrolia 1350 EVSC1Raghav DroliaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment IDocumento10 páginasAssignment IusmanjalaliAinda não há avaliações

- Hydro-Politics in Domestic and Regional ContextDocumento4 páginasHydro-Politics in Domestic and Regional Contexthannah50% (2)

- Water ConflitsDocumento22 páginasWater Conflitsanisha vAinda não há avaliações

- Water ConflitsDocumento22 páginasWater Conflitsanisha vAinda não há avaliações

- AUR-Centre For Water Studies - Report Sept 2011Documento12 páginasAUR-Centre For Water Studies - Report Sept 2011Debraj RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Nagaland State Water Policy 20162Documento19 páginasNagaland State Water Policy 20162mkbsbnbjhgjAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Water WomenDocumento117 páginas1 Water WomenVijay TateAinda não há avaliações

- The Past and Present Fisheries Situation in Beel Dakatia AreaDocumento7 páginasThe Past and Present Fisheries Situation in Beel Dakatia AreaPablo DybalaAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 Dirty Dozen Report Press ReleaseDocumento3 páginas2022 Dirty Dozen Report Press ReleaseMary LandersAinda não há avaliações

- Prevailing Problems of PakistanDocumento22 páginasPrevailing Problems of PakistanTariq KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Water Scarcity in Pakistan: Resource Constraint or MismanagementDocumento37 páginasWater Scarcity in Pakistan: Resource Constraint or MismanagementJournal of Public Policy PractitionersAinda não há avaliações

- Executive SummaryDocumento10 páginasExecutive Summarysaqib.ziaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Sharing Dispute in Pakistan Standpoint of Provinces PDFDocumento17 páginasWater Sharing Dispute in Pakistan Standpoint of Provinces PDFMuhammad Ali RazaAinda não há avaliações

- Sharing reservoirs' water for irrigation, drinkingDocumento16 páginasSharing reservoirs' water for irrigation, drinkingariefrizkiAinda não há avaliações

- An Assessment of Flood in KuttanaduDocumento8 páginasAn Assessment of Flood in KuttanaduSreelakshmiAinda não há avaliações

- Article On Water CresisDocumento5 páginasArticle On Water CresisJauhar AliAinda não há avaliações

- Water Scarcity A Potential Drain On The Texas EconomyDocumento5 páginasWater Scarcity A Potential Drain On The Texas Economynotdescript100% (1)

- July - August 2005 Irrigation Newsletter, Kings River Conservation District NewsletterDocumento2 páginasJuly - August 2005 Irrigation Newsletter, Kings River Conservation District NewsletterKings River Conservation DistrictAinda não há avaliações

- Water Resources & AgricultureDocumento9 páginasWater Resources & AgricultureInkspireAinda não há avaliações

- Agitation Against Polavaram: The Project It Is Proposed On The Godavari RiverDocumento5 páginasAgitation Against Polavaram: The Project It Is Proposed On The Godavari Riveraditya_erankiAinda não há avaliações

- India's Gigantic River Linking Project: Think About The Oceans Too! Sudhirendar SharmaDocumento2 páginasIndia's Gigantic River Linking Project: Think About The Oceans Too! Sudhirendar Sharmanaveen_k2004Ainda não há avaliações

- A State of Self Induced TragedyDocumento43 páginasA State of Self Induced TragedyDeven PatilAinda não há avaliações

- 2023-24 - Geography - 10-Notes Water - ResourcesDocumento4 páginas2023-24 - Geography - 10-Notes Water - ResourcesZoha AzizAinda não há avaliações

- Blue Gold: The Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's WaterNo EverandBlue Gold: The Fight to Stop the Corporate Theft of the World's WaterNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (16)

- Water Scarcity Diplomacy: Addressing the Challenges in the Nile River BasinNo EverandWater Scarcity Diplomacy: Addressing the Challenges in the Nile River BasinAinda não há avaliações

- Rescue ComDocumento16 páginasRescue ComshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- Brochure FinalDocumento31 páginasBrochure FinalshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- Directory of Indian Law FirmsDocumento37 páginasDirectory of Indian Law FirmsdeepahireAinda não há avaliações

- SILC Working DraftDocumento21 páginasSILC Working DraftBar & BenchAinda não há avaliações

- 2 King LearDocumento7 páginas2 King LearshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Drexel LRev 557Documento71 páginas2 Drexel LRev 557shashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- King Lear, Act 2 Scene 3: Ntroductory EctureDocumento3 páginasKing Lear, Act 2 Scene 3: Ntroductory EctureshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- Dabur Red CaseDocumento6 páginasDabur Red CaseshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- 3rd Yr. LL.B. Class Schedule Monsoon 2012Documento1 página3rd Yr. LL.B. Class Schedule Monsoon 2012shashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- Cauvery River Water Dispute: An AnalysisDocumento11 páginasCauvery River Water Dispute: An AnalysisshashvataryaAinda não há avaliações

- Kraft Cadbury MergerDocumento24 páginasKraft Cadbury MergerMahima Jain100% (2)

- The Definitive Guide to DamsDocumento35 páginasThe Definitive Guide to DamsMalia DamitAinda não há avaliações

- WEAP Iwrm JackSieberDocumento26 páginasWEAP Iwrm JackSieberAnonymous M0tjyWAinda não há avaliações

- Living Off Grid Guide Checklist Off Grid v1Documento4 páginasLiving Off Grid Guide Checklist Off Grid v1johnAinda não há avaliações

- Eco-Friendly Chemical-Free Desalination Solution IDE PROGREENTMDocumento4 páginasEco-Friendly Chemical-Free Desalination Solution IDE PROGREENTMlifemillion2847Ainda não há avaliações

- Terefe Final ThesisDocumento98 páginasTerefe Final ThesisBegna BulichaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Resources EngineeringDocumento48 páginasWater Resources EngineeringknightruzelAinda não há avaliações

- Nalgonda Water InformationDocumento23 páginasNalgonda Water InformationManaswini ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Helix Power Flywheel - MBTA ReportDocumento2 páginasHelix Power Flywheel - MBTA ReportAnonymous 0YIzyrmqHAinda não há avaliações

- Penanganan Clay Shale FinalDocumento37 páginasPenanganan Clay Shale FinalabelAinda não há avaliações

- Ministry of Science and Technology: Sample Questions & Worked Out Examples For CE-04026 Engineering HydrologyDocumento24 páginasMinistry of Science and Technology: Sample Questions & Worked Out Examples For CE-04026 Engineering HydrologyShem Barro67% (3)

- Rock Cycle Webquest PDFDocumento6 páginasRock Cycle Webquest PDFapi-268569185Ainda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Wind Energy: James Mccalley Honors 322W, Wind Energy Honors SeminarDocumento28 páginasIntroduction To Wind Energy: James Mccalley Honors 322W, Wind Energy Honors SeminarMohammed Al-OdatAinda não há avaliações

- Economic Analysis Report for HEIS Crop ProjectDocumento4 páginasEconomic Analysis Report for HEIS Crop ProjectAqeel SaleemAinda não há avaliações

- Calss X Geography Chapter Agriculture Extra Questions Worksheet-2Documento6 páginasCalss X Geography Chapter Agriculture Extra Questions Worksheet-2Vivek bishtAinda não há avaliações

- LID Hydrology National ManualDocumento45 páginasLID Hydrology National ManualAnnida Unnatiq UlyaAinda não há avaliações

- Nagaland State Water Policy 20162Documento19 páginasNagaland State Water Policy 20162mkbsbnbjhgjAinda não há avaliações

- 251 - LicMap Licences 1 - 2000000 - 11-06-2017 - 08.40.16Documento1 página251 - LicMap Licences 1 - 2000000 - 11-06-2017 - 08.40.16Peter WatsonAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 Nigerian Oil & Gas Annual Report HighlightsDocumento75 páginas2015 Nigerian Oil & Gas Annual Report HighlightsReaderbank0% (1)

- Guidelines For Desilting DamsDocumento2 páginasGuidelines For Desilting DamsrichlogAinda não há avaliações

- Barsha Pump: Name:-Amlan Panda REGN.: - 20020092 ROLL NO: - MEE20L08Documento11 páginasBarsha Pump: Name:-Amlan Panda REGN.: - 20020092 ROLL NO: - MEE20L08Amlan panda100% (1)

- Green Peace Letter To Herakles Capital - Signed May 10 2012Documento2 páginasGreen Peace Letter To Herakles Capital - Signed May 10 2012cameroonwebnewsAinda não há avaliações

- Agribusiness in Rural Development: A Case of Organic Mango CultivationDocumento14 páginasAgribusiness in Rural Development: A Case of Organic Mango CultivationMohidul sovonAinda não há avaliações

- Crop Calendar PakistanDocumento48 páginasCrop Calendar PakistanAli RazaAinda não há avaliações

- Expo 1Documento24 páginasExpo 1svblzambiaAinda não há avaliações

- What-Is-A-Watershed-Webquest StudentworksheetDocumento5 páginasWhat-Is-A-Watershed-Webquest Studentworksheetapi-264569897Ainda não há avaliações

- Flood Risk Assessment and Modelling A K LohaniDocumento34 páginasFlood Risk Assessment and Modelling A K LohaniswapnillohaniAinda não há avaliações

- Iadc Brocas PDCDocumento1 páginaIadc Brocas PDCCamila PalaciosAinda não há avaliações

- SIP Sustainable Drainage SolutionDocumento5 páginasSIP Sustainable Drainage SolutionElyAinda não há avaliações

- Liquefaction Hazard: Jonathan D. Bray, PHD, Pe, NaeDocumento56 páginasLiquefaction Hazard: Jonathan D. Bray, PHD, Pe, NaeMariaAinda não há avaliações

- Canal Irrigation Is An Important Means of Irrigation and Is More Common in The Northern Plains BecauseDocumento1 páginaCanal Irrigation Is An Important Means of Irrigation and Is More Common in The Northern Plains BecausegknindrasenanAinda não há avaliações