Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Teacher Job Satisfaction and Burnout Viewed Through

Enviado por

Nikoleta HirleaDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Teacher Job Satisfaction and Burnout Viewed Through

Enviado por

Nikoleta HirleaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Agricultural Education

Volume 53, Number 1, pp 3144

DOI: 10.5032/jae.2012.01031

Teacher Job Satisfaction and Burnout Viewed through

Social Comparisons

Tracy Kitchel, Associate Professor

University of Missouri

Amy R. Smith, Assistant Professor

South Dakota State University

Anna L. Henry, Associate Professor

University of Missouri

J. Shane Robinson, Associate Professor

Oklahoma State University

Rebecca G. Lawver, Assistant Professor

Utah State University

Travis D. Park, Associate Professor

Cornell University

Ashley Schell, former Graduate Assistant

University of Kentucky

Understanding job satisfaction, stress, and burnout within agricultural education has the potential to

impact the professions future. Studying these factors through the theoretical lens of social comparison

takes a cultural approach by investigating how agriculture teachers interact with and compare

themselves to others. The purpose of this study was to determine if relationships existed between social

comparison and job satisfaction and/or burnout among secondary agriculture teachers representing six

states. Findings indicated that teachers were satisfied with their jobs and tended to engage most

frequently in upward assimilative (UA) comparisons, leading to inspiration emotional outcomes.

According to the Maslach Burnout Inventory for Educators (MBIE), teachers experienced low levels of

burnout related to personal accomplishment (PA) and depersonalization (DE), and moderate levels

related to emotional exhaustion (EE). Seven moderate relationships were found between dimensions of

social comparison and either burnout and/or job satisfaction.

Keywords: social comparison; agriculture teachers; job satisfaction; teacher burnout

Introduction

well beyond a typical teacher workweek

(Torres, Lambert, & Tummons, 2009). As a

result, research and professional development

initiatives in agricultural education have

addressed the retention and development of

schoolbased agriculture teachers who are

committed to and adept in managing a unique

compilation of workplace demands (Mundt &

Connors, 1999; Myers, Dyer, & Washburn,

2005).

Certainly, by understanding job

satisfaction, stress, and burnout within

agricultural education better, teacher educators

Teaching is a demanding occupation, at any

level, within any content area. This is partially a

result of high expectations in relation to state

and national standards, and deadlines imposed to

increase student learning (Strauss, 2002).

However, some would argue that teaching

agriculture is even more demanding given that

the roles of an agricultural educator are multi

faceted (Roberts & Dyer, 2004). Additionally,

the workload of an agricultural educator extends

31

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

may be able to prepare future teachers more

appropriately and assist those who are currently

in the profession.

To ensure retention of a highly qualified

group of professionals within agricultural

education, job satisfaction must be addressed.

Within other areas of social science research, job

satisfaction has been studied widely, often in

relation to qualities such as productivity,

performance, absenteeism, and job turnover

(Jewell, Beavers III, Malpiedi, & Flowers, 1990,

p. 52). In general, job satisfaction is described as

an individuals feelings about his or her job and

is dependent on individual attitudes and levels of

motivation toward performing tasks associated

with a job (Gilmer & Deci, 1977). A satisfied

worker is more effective and productive than an

unsatisfied worker (Martin, 2002).

And,

satisfied workers tend to be more committed to

their careers (Robinson & Garton, 2006).

Subsequently, job satisfaction can impact

career longevity and tenure. Job tenure, on

average, has decreased from seven to four years

(Gregg & Wadsworth, 1995 as cited in Morley,

2001). In fact, employees are job hopping

more now than ever before (Boverie & Kroth,

2000).

To more fully understand career

commitment and potential job tenure among

secondary agriculture teachers, research should

examine teacher satisfaction with their chosen

careers.

Although numerous scales for measuring job

satisfaction exist, the BrayfieldRothe (1951)

job satisfaction instrument, as modified by

Warner (1973) is one of the most commonly

used in agricultural education research.

Specifically, this instrument has been used by

researchers in agricultural education to study

faculty at higher education institutions (Bowen

& Radhakrishna, 1991; Castillo & Cano, 2004),

secondary agricultural education instructors

(Bruening & Hoover, 1991; Cano & Miller,

1992a; Cano, & Miller, 1992b; Castillo & Cano,

1999; Castillo, Conklin, & Cano, 1999;

Newcomb, Betts, & Cano, 1986; Walker,

Garton, & Kitchel, 2004), agricultural education

graduates (Garton & Robinson, 2006; Robinson

& Garton, 2008), and supervisors of agricultural

employees (Barrick, 1989).

Although

personal

and

professional

characteristics data (i.e. demographics) are not

good predictors of job satisfaction (Bruening &

Radhakrishna, 1991; Cano & Miller, 1992a;

Journal of Agricultural Education

Cano & Miller; 1992b; Castillo & Cano, 1999),

it is possible that discrepancies might exist

among faculty members across the country; as

such, Bowen and Radhakrishna (1991)

recommended that comparisons should be made.

The same recommendation could be made for

secondary agriculture teachers. How does job

satisfaction differ among teachers in various

states? Cano and Miller (1992b) opined that

teachers who leave the profession likely do so

because of their lack of job satisfaction.

Therefore, studying job satisfaction among a

wide range of teachers across multiple states

could have implications for understanding how

to retain teachers in the profession longer

(Walker et al., 2004).

Discrepancy exists in the literature regarding

job satisfaction of secondary teachers in

agriculture. Cano and Miller (1992a) found that,

when considering each facet of their job,

agriculture teachers were undecided on their

level of overall job satisfaction. In contrast,

Walker et al. (2004) determined that teachers

were satisfied generally with their jobs

regardless of whether they stayed, moved

within, or left the profession for another career.

The authors found that teachers who left the

profession were just as satisfied as those who

stayed, but the reasons they left were due to a

perceived lack of administrative support (p.

35) and issues involving their family, which

could have led to high levels of stress for these

teachers.

An important emotional precursor to job

satisfaction, documented in the literature widely,

is the level of stress associated with a job.

Specifically, agriculture teachers experience

challenges that form particular job stressors

(Greiman, Walker, & Birkenholz, 2005; Walker

et al., 2004). Symptoms of stress in teachers can

include anxiety and frustration, impaired

performance, and damaged interpersonal

relationships at work and at home (Kyriacou,

2001). Teachers who experience stress over

long periods of time may then experience

burnout (Troman & Woods, 2001). Working

long hours, usually beyond a 40hour work

week (Straquadine, 1990; Vaughn, 1990),

contributes to the stress level of agriculture

teachers, and leads ultimately to burnout in

many cases. Indicators of burnout are a loss of

idealism and enthusiasm for work (Matheny,

Gfoerer, & Harris, 2000). Burnout has also

32

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

been characterized as an extreme type of role

specific alienation with a focus on feelings of

meaninglessness, especially as this applies to an

individuals

ability

to

reach

students

successfully (LeCompte & Dworkin, 1991).

Those who experience burnout may struggle

with finding the desire and motivation to

continue in their current profession. Research

by Maslach, Jackson, and Leiter (1996) has

highlighted three important reasons to study

teacher burnout citing, (a) teaching is an

extremely visible profession; (b) teachers are

expected to teach beyond academics into moral

development to correct social problems; and (c)

meeting diverse needs and expectations of

students requires numerous human and financial

resources. To that end, Maslach et al. (1996)

developed an educator version of their burnout

inventory to measures dimensions of emotional

exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal

accomplishment among teachers. The results of

research in agricultural education indicated that

agriculture teachers, overall, are not stressed and

are satisfied with their jobs (Chenevey, Ewing,

& Whittington, 2009; Torres, Lawver, &

Lambert, 2009). Yet, there are agriculture

teachers who are reaching the tipping point of

job burnout due to the job pressures and

demands (Torres et al., 2009). The requirements

of the job and the resources available to do the

job are often mismatched, leading to stressful

situations and burnout. In addition, teachers

with higher levels of emotional exhaustion are

those who are more likely to experience burnout

(Chenevey, et al., 2009).

Most of the studies associated with job

satisfaction and burnout in agricultural education

are associated with personal or demographic

variables. Another approach may be to assess

cultural or contextual variables. In discussing a

related topic teacher quality Kennedy

(2010) argued that education has succumbed to

the fundamental attribution error (p. 591) by

overlooking situational or contextual factors that

may also continue to affect teacher quality. If

this argument is true for job satisfaction and

teacher burnout, then a different approach is

warranted. One approach is to assess how

teachers interact within the profession of

agricultural education.

Agriculture teachers have numerous

opportunities (i.e., at local, regional, state, and

national

meetings,

competitions,

and

Journal of Agricultural Education

conferences) to interact (and thus compare)

themselves to other agriculture teachers on a

more individual level. This presents a unique

context in which to study social comparison, and

implications that such an environment might

have on retaining and developing agriculture

teachers who are more satisfied in their

professions, less stressed, and less likely to

experience the phenomenon of burnout.

The social comparison theory is a theoretical

framework that could be used to explain how

agriculture teachers act because, according to

Festinger (1954), social comparison can be used

within a professional culture. According to the

theory, certain emotional outcomes may result in

either positive or negative satisfaction and stress

that could lead to burnout.

Festinger

hypothesized that people have the desire to

evaluate their own opinions and abilities in

relation to the opinions and abilities of others.

For example, a persons evaluation of his

ability to write poetry will depend to a large

extent on the opinions which others have of his

ability to write poetry (p. 118). Consequently,

individuals who make frequent social

comparisons should be happy if they believe

they are better off than those with whom they

compare themselves (Wood, Taylor, &

Lichtman, 1985).

Social comparison has been intertwined with

selfevaluation and has affected individuals

selfesteem, even functioning as a coping

mechanism (Wills, 1981). Social comparison

has been used to manage negative affect

(Aspinwall & Taylor, 1983) and to affiliate

upward (Collins, 1996). Under stress, people

are more likely to compare themselves to those

who are in worse situations (Taylor & Lobel,

1989).

To understand the theory, it is essential to

recognize that social comparisons can be

directional. People can make upward and

downward comparisons. Individuals engage in

upward comparison when comparing themselves

to peers whom they perceive are performing

more competently or adequately than they are.

Individuals engage in downward comparison

with peers when they compare themselves to

those whom they perceive are performing in a

less competent or inadequate ways (Carmona et

al., 2006).

In addition, social comparisons can be

contextually set as either assimilative or

33

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

contrastive in nature (Smith, 2000). Social

judgments are based strongly on some context

and the values or standards associated with that

context (Wedell, 1994). According to Wedell,

contrast refers to the displacement of

judgments away from the values of contextual

stimuli. . . assimilation, on the other hand, refers

to the displacement of judgment toward the

contextual standard (1994, p. 1007). For

example, when someone makes a comparison to

another whom they perceive as better than they

are (an upward comparison), then the

comparison can lead to either assimilative,

emotional responses of inspiration and optimism

or it can lead to contrastive, emotional outcomes

of envy and resentment (Smith, 2000).

All types of social comparisons may have

emotional consequences. People feel relieved

when they see that others are doing worse, and

feel envious when they see that others are doing

better than them (Buunk & Ybema, 1997).

When comparing upward, individuals may be

inspired because they feel like they have become

the comparison target.

In contrast, when

comparing downward, individuals may lose their

good feeling about themselves because they fear

ending up in a similar situation (Buunk &

Ybema, 2004).

Recognizing

that

teachers

compare

themselves frequently to others in the

profession, research has been conducted relating

social comparison to teacher burnout (Caromona

et al., 2006). The findings indicated that when

teachers compare themselves with others whom

they feel are performing at a lower level, and

they feel that this comparison is a negative

experience, they are more likely to experience

job burnout.

Further research has been

conducted to determine if practicing teachers

responded differently to upward and downward

social comparison in terms of affect and the

intent to work harder (Van Yperen,

Brenninkmeijer, & Buunk, 2006). The findings

indicated that practicing teachers respond

differently to upward and downward social

comparison information. The personal belief of

exerting effort to do a job well was correlated to

positive affect after upward, social comparison.

With consideration given to the cultural

structure of the agricultural education

profession, and the closeknit, collegial nature

of those within the profession, the social

comparison theory seems particularly applicable.

Journal of Agricultural Education

Social comparison could be programmatic in

nature, occurring through multiple venues such

as competition in FFA, at conferences, or

conventions. As described earlier, emotional

outcomes could ensue based on how social

comparison manifests. It is important to assess

the culture of the agricultural education

profession through the lens of social comparison

as such a lens may provide rationale for the

positive and/or negative emotional results that

represents the unique context of the agricultural

education profession.

Purpose and Methods

The purpose of this descriptiverelational

study was to determine if relationships existed

between social comparison and job satisfaction

and between social comparison and teacher

burnout.

The following objectives were

developed to guide the study:

1. Determine the degree of social comparison

in which agriculture teachers engage.

2. Determine the level of job satisfaction of

agriculture teachers.

3. Determine the degree of teacher burnout

experienced by agriculture teachers.

4. Determine the relationship between social

comparison and job satisfaction.

5. Determine the relationship between social

comparison and teacher burnout.

The population of the study was high school

agriculture teachers from six states (Kentucky,

Missouri, New York, Oklahoma, South Dakota,

Utah). For each respective state, a frame was

identified, which provided contact information

for all current high school agriculture teachers.

Each frame was then scrutinized for errors,

omissions, and duplications to address potential

frame error and to ensure accuracy.

A random sample was selected from the

frames of two states with agriculture teacher

populations larger than 300 (Missouri and

Oklahoma).

For the remaining states, all

teachers were invited to participate in the study

because the difference between the size of those

states populations and the size required for a

representative sample was small. In addition,

the geographic spread of the states involved was

considered a beneficial factor. One state was

located in the southern region of the United

34

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

States (Kentucky), one from the east (New

York), two from the Midwest (Missouri and

South Dakota), one from the southwest

(Oklahoma) and another from the west (Utah).

As such, readers are cautioned on inferring the

results beyond the scope of this study as findings

can only be generalized to the high school

agriculture teachers from the six states who

participated.

An online instrument was utilized to collect

data and was distributed via email using

HostedSurvey, a webhosted software

application. The instrument consisted of three

key sections, as well as a demographic section.

The three sections (Social Comparison, Job

Satisfaction, and Teacher Burnout) are outlined

below.

A panel of experts, consisting of faculty and

individuals familiar with the agriculture teacher

role, reviewed the instrument for face and

content validity. Further, the instrument was

pilottested using 19 agriculture teachers from a

state not utilized in this study. Calculations

using Cronbachs alpha indicated coefficients of

.75 (DA), .76 (DC), .89 (UC), and .91 (UA).

Because coefficients were above .70, the

instrument was deemed reliable (Nunnally,

1967).

Job Satisfaction

Castillo and Cano (2004) sought to

determine if a oneitem measure of job

satisfaction was as valid as a multiitem

measure. The researchers standardized and

compared (p. 71) the oneitem instrument to

the multiitem instrument and found no

differences existed in scores. As such, they

concluded that a oneitem instrument could

assess an individuals level of job satisfaction

adequately. Therefore, for the purpose of this

research, job satisfaction was assessed by asking

teachers to respond with their level of agreement

to the question, How satisfied are you with

your job? The singleitem question required a

response on a rating scale with seven descriptors

ranging from strongly dissatisfied to strongly

satisfied.

Social Comparison

To measure social comparison and the

dimensions

of

upward/downward

and

contrastive/assimilative, the Social Comparison

Style

Questionnaire

(SCSQ)

instrument

developed by Leach et al. (n.d.) was utilized.

There were four constructs to this section of the

instrument: downward assimilation (DA),

downward contrast (DC), upward contrast (UC),

and upward assimilation (UA). DA was aligned

with the emotion worry. An example item in

this construct was, learning that another

agriculture teacher is worse off than I suggests

that my situation might get worse in the future

as well. UA was aligned with the emotion

inspiration. An example item in this construct

was, agriculture teachers who are more

successful than I excite and/or challenge me to

do better. DC was aligned with the emotion

gratitude. An example item in this construct

was, seeing agriculture teachers with difficult

working conditions really helps me appreciate

my own life. UC was aligned with inferiority.

An example item in this construct was, I often

feel angry that Im not as competent of an

agriculture teacher as others. Because of the

contextspecific nature of social comparison,

items were revised from the original instrument

(Leach et al., n.d.) to provide focus to a person

comparing him/herself to other agricultural

education teachers and/or their program. SCSQ

uses summated rating scales, consisting of seven

questions for UC, five for UA, four for DA, and

three for DC.

Journal of Agricultural Education

Burnout

The Maslachs Burnout Inventory for

Educators (MBIE) was utilized to measure

burnout. The MBIE was selected because of its

specific application to teachers and measurement

of multiple dimensions of burnout. In particular,

the MBIE measured three burnout subscales

including

Emotional

Exhaustion

(EE),

Depersonalization

(DP),

and

Personal

Accomplishment (PA). Emotional exhaustion is

described as the tired and fatigued feeling that

develops as emotional energies are drained,

while depersonalization refers to the act of

portraying negative or indifferent attitudes

towards ones students (Maslach et al., 1996, p.

28). The third subscale measures personal

accomplishment which may indicate a teachers

feelings regarding the contributions they are

making to student growth and achievement

(Maslach et al., 1996). A total of 22 items

comprised

the

commercially

available

instrument, which has been assessed for validity

35

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

and reliability. Two factor analysis studies,

conducted between 1981 and 1984 supported the

use of three subscales (Gold, 1984; Iwanicki &

Schwab, 1981). With regard to reliability,

researchers reported Cronbachs alpha reliability

estimates ranging from .72 to .90.

invited 944 participated in the study, providing a

response rate of 40.57%.

Data Analysis

Objectives 13 were analyzed using means

and standard deviations for the scaled items.

Objectives 45 were analyzed using the Pearson

productmoment correlation using social

comparison as the variable of interest. Davis

(1971) conventions were used to interpret

correlation coefficients. For all analyses, only

descriptive statistics were reported because the

sample was not inferential.

Data Collection

Using features offered by HostedSurvey,

a modified version of the Dillmans (2007)

Tailored Design Method guided data collection.

Typically, this method is utilized for mailed

instruments and includes five contacts (Dillman,

2007). However, because this instrument was

delivered via email, the contacts were modified

slightly. Immediately prior to the first email

invitation, a key contact from each respective

state sent a personalized message to the teachers

within their state. This was done to introduce

the idea of the study to the teachers, prior to

receipt of the first email, in effort to increase the

overall response rate. One day after this pre

notice was sent, teachers received the first

invitation to participate.

Two additional

contacts were made with those teachers who had

not completed the instrument; these were sent at

oneweek intervals. As a result, 383 out of the

Findings

With objective one, the researchers sought

to determine the degree of social comparison in

which agriculture teachers engage. Agriculture

teachers engage in upward assimilation (M =

4.58; SD = 0.75) predominantly, meaning as

they compare themselves to someone perceived

as better, they engage in emotions relating to

inspiration (Table 1). Teachers engaged in DC

gratitude, UC inferiority, and DA worry in order

of declining succession.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Social Comparison Dimensions (n = 383)

Variable or Construct

Mean

Standard Deviation

Social Comparison Construct

Upward Assimilation (UA) Inspiration 1

4.58

0.75

Downward Contrast (DC) Gratitude 1

3.94

0.92

Upward Contrast (UC) Inferiority 1

2.42

0.95

Downward Assimilation (DA) Worry 1

2.12

0.84

Note. 1 Based on a scale from 1 to 6, with 1 as strongly disagree and 6 as strongly agree

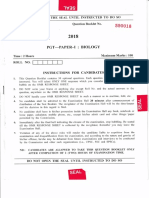

With objective two, the researchers sought

to determine the level of job satisfaction of

agriculture teachers. Agriculture teachers were

satisfied with their job (M = 6.04; SD = 1.06),

measured on a single item scaled 1 to 7, with 1

being strongly dissatisfied and 7 being strongly

satisfied. To determine the degree of teacher

burnout experienced by agriculture teachers

Journal of Agricultural Education

(Objective 3), researchers found that they

experience low levels of burnout on the

depersonalization construct and low levels on

the

personal

accomplishment

construct

according to the MBIE (Figure 1). However,

agriculture teachers experienced moderate

levels of burnout on the emotional exhaustion

construct.

36

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

M = 20.27, SD = 11.01

Emotional Exhaustion1

16 17

M = 6.92, SD = 5.79

Depersonalization2

Personal Accomplishment3

26 27

8 9

M = 37.83, SD = 6.34

13 14

37 36

Low

31 30

Moderate

High

Figure 1. Teacher burnout scale measured by the MBIE. Interpretations: 1EE = high (27 or over),

moderate (1726) and low (016). 2DP = high (14 or over), moderate (913) and low (08). 3PA

(interpreted in reverse of EE/DP) = low (37 or over), moderate (3136) and high (030).

With objective four, researchers sought to

determine the relationship between social

comparison and job satisfaction, and with

objective five, they sought to determine the

relationship between social comparison and

teacher burnout.

Pearson productmoment

correlation coefficients were calculated to

determine these relationships. Note that when

interpreting the burnout construct of personal

accomplishment (PA), higher mean scores

indicated lower levels of burnout; therefore a

negative relationship using PA indicates that the

more one engaged in social comparison the more

burnout (on this scale) that tended to exist. The

strongest relationships existed with upward

contrastive (Table 2).

Table 2

Correlation Coefficients for Social Comparison with Job Satisfaction and Teacher Burnout

Social Comparison Construct

Job Satis. (JS)

Burnout: PA1

Burnout: EE2

Burnout: DP3

Upward Contrast (UC)

-0.40

-0.29

0.44

0.40

Upward Assimilation (UA)

0.35

0.29

-0.17

-0.12

Downward Contrast (DC)

-0.37

-0.27

0.39

0.30

Downward Assimilation (DA)

0.16

0.16

-0.13

-0.05

Note. 1PA = Personal Accomplishment; 2EE = Emotional Exhaustion; 3DP = Depersonalization

As such, the more that agriculture teachers

tended to engage in comparisons of other, more

effective agriculture teachers, and when those

comparisons led to feelings of inferiority, the

more their satisfaction decreased (r = -0.40) and

their burnout levels increased (rPA = -0.29; rEE =

0.44; rDP = 0.40).

Note that Personal

Accomplishment (PA) is interpreted in reverse

as compared to the other two scales. Downward

assimilation elicited the lowest strength of

correlation.

Journal of Agricultural Education

Discussion

Although the study included a large sample

representing six states in all geographic regions

of the country, the results should be interpreted

with caution. The study is limited by a 40%

response rate, and not every state was

represented. Thus, findings should not be

generalized beyond teachers in the states

studied.

For research objective one, it was concluded

that agriculture teachers engaged mostly in the

social comparison of upward assimilation.

Thus, agriculture teachers in this study make

37

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

upward comparisons of themselves to other

teachers whom they admire, look up to, or are

inspired by. This finding supports the assertion

by Smith (2000) who found that teachers make

upward comparisons with those whom they

perceive that they might be able to achieve

similar accomplishments (Smith, 2000). This

finding could imply that agriculture teachers are

in a positive, emotional state as they compare

themselves with others. It would stand to reason

that agriculture teachers who engage in upward

assimilation as a form of social comparison want

positive outcomes for their colleagues and for

themselves through their admiration of other

successful teachers.

Also, they could be

engaged positively by others successes. This

implication would be consistent with research

that suggests that teachers who engage in

upward, social comparison believe that, with

effort, they too will improve and grow in

productive professional directions (Van Yperen,

Brenninkmeijer, & Buunk, 2006).

Further

research is needed to investigate influences of

social comparison on motivation, teaching self

efficacy, and measures of teacher success in the

classroom.

It was also concluded that some agriculture

teachers in this study engaged in downward,

contrastive social comparison toward their

colleagues. Thus, some teachers, when making

social comparisons, look down on others and

experience feelings of contempt, scorn, and

pride (Smith, 2002). This finding implies that

agriculture teachers might scorn and have

negative attitudes about their colleagues whom

they feel are not doing as good of a job as them.

The notion of agriculture teachers engaging in

downward, contrastive emotions toward their

colleagues poses interesting questions. Does the

professional culture in agricultural education

create a situation where teachers wear their jobs

as a badge of honor and scorn others whom they

feel are not performing to the same level?

Because comparisons are perceptionbased,

each persons comparison of worse off

(downward comparison) is different. Based on

this premise, worse off could be merely a

question of being different. Thus, does the

professional culture allow for teachers who

perform the job in different ways, or do

professionals scorn others who are perceived as

being different? The results of this study

certainly do not point social comparison in any

Journal of Agricultural Education

causeeffect direction.

However, further

research is needed in social comparison

regarding the types of individuals teachers make

social comparisons toward and specific

situations in which they compare themselves

socially with others. Of primary interest in

future research is how teachers frame upward

(better off) and downward (worse off)

comparisons.

It was concluded in this study that

agriculture teachers are satisfied with their job,

which is consistent with previous literature

(Walker at al., 2004). This finding could imply

that individuals who took the time to complete

the questionnaire were likely those who would

be more satisfied with their job in the first place.

Although teachers are satisfied generally, further

research is needed to investigate the specific

sources of their satisfaction, conditions, or

factors of their jobs that are the most and least

satisfying. Agricultural education researchers

should also be interested in motivators and

barriers for individuals who are least satisfied

with their jobs.

It is recommended that

professional development programs designed to

recruit and retain agriculture teachers utilize this

finding as a means to communicate to the public

that many teachers report that they are satisfied

with teaching agriculture.

It was concluded that teachers are

experiencing low levels of burnout as it pertains

to

depersonalization

and

personal

accomplishment;

however,

teachers

are

experiencing moderate levels of burnout as it

pertains to emotional exhaustion. This finding

could imply that while teachers in this study

might not be feeling alienated toward their

profession or their ability to perform well as

teachers (LeCompte & Dworkin, 1991), they

could be feeling the emotional implications of a

complex and multifaceted career.

Further

research is needed regarding the specific sources

of emotional exhaustion for agriculture teachers.

Further research is also needed regarding the

specific factors that help combat emotional

exhaustion in agriculture teachers. Professional

development programs for agriculture teachers

should keep indicators of emotional exhaustion

in mind and design uplifting programs that

empower teachers emotionally.

In regard to the relationship between social

comparison and job satisfaction, it was

concluded that teachers who compared

38

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

themselves to others and felt feelings of

inferiority as a result were less likely to

experience feelings of satisfaction with their

jobs. Further, teachers who compared

themselves to others and felt inspired by others

accomplishments were more likely to experience

feelings of satisfaction with their jobs. Finally,

teachers who compared themselves to others

whom they looked down on with appreciation

that they were not in that same place were less

likely to experience feelings of satisfaction with

their jobs. Findings regarding the relationships

between social comparison and job satisfaction

pose interesting implications. For example, the

findings could imply that positive emotions of

others (social comparison) and positive outlook

for the self (job satisfaction) vary together.

One question for further research, and hence

a limitation of correlational studies, is that from

this study it cannot be determined which

emotional outcome (if any) serves as the cause

or the precursor to the other. Do people who

like their jobs tend to feel positive about others

in a profession, or do feelings of connection and

positivity within a profession lead to higher job

satisfaction? Further, it was concluded that

negativity in terms of social comparison and job

satisfaction varied together as well. Again,

further research is needed regarding the specific

causes of and precursors to the negative,

emotional outcomes of contrastive, social

comparison and job dissatisfaction. Further

research is needed regarding the social and

emotional climate of agricultural education as a

profession. Do local and statewide teacher

associations in agricultural education foster a

climate of sameness, and what effect does the

climate have on teachers?

Professional

development programs for agriculture teachers

should take emotional concerns of satisfaction,

social

comparison

and

burnout

into

consideration.

Programs should be designed

with those who are less satisfied emotionally in

mind.

Regarding social comparison and teacher

burnout, it was concluded that teachers who

experienced upward, assimilative emotions of

social comparison felt more personal

accomplishment, less emotional exhaustion, and

fewer feelings of depersonalization. Further,

Journal of Agricultural Education

teachers who felt a sense of envy or depression

when thinking about more successful colleagues

also felt fewer feelings of personal satisfaction,

more feelings of emotional exhaustion, and more

feelings of depersonalization toward their career.

Finally, teachers who look down on colleagues

they deemed worse off with scorn also felt less

personal satisfaction toward their careers, more

emotional exhaustion, and experienced more

feelings of depersonalization toward their

careers. These findings are consistent with the

Carmona et al. (2006) investigation of the

relationships between social comparison and

burnout. Again, these findings point toward the

notion of positivity and its potential

implications. Although it might be no surprise

those positive, social feelings and positive

outcomes (lack of burnout or greater

satisfaction) would increase together, again, the

question regarding causation remains. Are

people who are drawn naturally to a profession,

more successful, positive, and satisfied about it,

and less burned out? Conversely, is ignorance

bliss? Meaning, are those who are blissfully

satisfied, less burned out and happier with others

socially?

Regardless, further research is

warranted regarding both positive and negative

emotions in agriculture teachers and the effects

of teacher affect on teacher success and student

outcomes.

Finally,

teacher

professional

development programs should be based on the

notion of positive psychology and emotional

outcomes and seek to foster feelings of positive

emotions in teachers at all levels.

In looking strictly at future directions for

this line of inquiry, one of the dimensions this

study did not address was frequency of

comparison. This study focused on the nature of

the comparisons only (upward/downward and

assimilative/contrastive). It is a dimension that

both this study and most of the literature in the

field do not address. In addition, layering the

dimensions of frequency and nature could bring

about more specific information regarding job

satisfaction and burnout. Another aspect this

study did not address was potential precursor

variables to social comparison.

Perhaps

identifying other variables, characteristics, or

behaviors could enlighten the field on this

phenomenon.

39

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

References

Altermatt, E. R., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2005). The implications of having highachieving versus low

achieving friends: A longitudinal analysis. Social Development, 14(1), 6181. doi: 10.1111/j.14679507.2005.00291.x

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and selfesteem on

affect, selfevaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64,

708722. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.708

Barrick, R. K. (1989). Burnout and job satisfaction of vocational supervisors. Journal of Agricultural

Education, 30(4), 3541. doi: 10.503/jae.1989.04035

Blanton, H., Buunk, A. P., Gibbons, F. X., & Kuyper, H. (1999). When betterthanothers compare

upward: Choice of comparison and comparative evaluation as independent predictors of academic

performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 420430. doi: 10.1037/00223514.76.3.420

Boverie, P., & Kroth, M. (2000). A passion for work: Developing and maintaining motivation. Motivation

Symposium 33: RaleighDurham, NC.

Bowen, B. E., & Radhakrishna, R. B. (1991). Job satisfaction of agricultural education faculty: A constant

phenomena. Journal of Agricultural Education, 32(2), 1622. doi: 10.5032/jae.1991.02016

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951, October). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 35, 305311. doi: 10.1037/h0055617

Bruening, T. S., & Hoover, T. S. (1991). Personal life factors as related to effectiveness and satisfaction of

secondary agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 32(4), 3743. doi:

10.5032/jae.1991.04037

Butler, R. (1998). Age trends in the use of social and temporal comparison for selfevaluation: Examination

of a novel developmental hypothesis. Child Development, 69(4), 10541073. doi: 10.1111/j.14678624.1998.tb06160.x

Buunk, A. P., & Ybema, J. F. (1997). Social comparisons and occupational stress: The identification

contrast model. In B. P. Buunk & F. X. Gibbons, (Eds), Health, coping and wellbeing:

Perspectives from social comparison theory (pp. 359388) Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buunk, A. P., & Ybema, J. F. (2004). Feeling bad, but satisfied: The effects of upward and downward

comparison upon mood and marital satisfaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 613628.

doi: 10.1348/014466603322595301

Cano, J., & Miller, G. (1992a). A gender analysis of job satisfaction, job satisfier factors, and job

dissatisfier factors of agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 33(3), 40

46. doi: 10.5032/jae.1992.03040

Cano, J., & Miller, G. (1992b). An analysis of job satisfaction and job satisfier factors among six

taxonomies of agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 33(4), 916. doi:

10.5032/jae.1992.04009

Journal of Agricultural Education

40

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

Carmona, C., Buunk, A. P., Peiro, J. M., Rodriguez, I., & Bravo, M. J. (2006). Do social comparison and

copying styles play a role in the development of burnout? Crosssectional and longitudinal

findings. Journal of Occupational and Organization Psychology, 79, 8599.

Castillo, J. X., & Cano, J. (2004). Factors explaining job satisfaction among faculty. Journal of Agricultural

Education, 45(3), 6574. doi: 10.5032/jae.2004.03065

Castillo, J. X., & Cano, J. (1999). A comparative analysis of Ohio agriculture teachers level of job

satisfaction. Journal of Agricultural Education, 40(4), 6776. doi:10.532/jae.1999.04.067

Castillo, J. X., Conklin, E. A., & Cano, J. (1999). Job satisfaction of Ohio agricultural education teachers.

Journal of Agricultural Education, 40(2), 1927. doi: 10.5032/jae.1999.02019

Chenevey, J. L., Ewing, J. C., & Whittington, M. S. (2008). Teacher burnout and job satisfaction among

agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(3), 1222, doi

10.532/jae.2008.03012

Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on selfevaluations.

Psychological Bulletin, 119, 5169. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

Davis, J. A. (1971). Elementary survey analysis. Englewood, NJ: PrenticeHall.

Feldman, N. S., & Ruble, D. N. (1977). Awareness of social comparison interest and motivations: A

developmental study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(5), 579585. doi: 10.1037/00220663.69.5.579

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117140. doi:

10.1177/001872675400700202

Garton, B. L., & Robinson, J. S. (2006). Career paths, job satisfaction, and employability skills of

agricultural education graduates. NACTA Journal, 50(4), 3136.

Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, A. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale

of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 129142.

doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.129

Gilmer, B., & Deci, E. (1977). Industrial and organizational psychology. New York, NY: McGrawHill.

Greiman, B. C., Walker, W. D., & Birkenholz, R. J. (2005). Influence of the organizational environment on

the induction stage of teaching. Journal of Agricultural Education, 46(3), 95106. doi:

10.5032/jae.2005.03095

Jewell, L. R., Beavers III, K. C., Malpiedi, B. J., & Flowers, J. L. (1990). Relationships between levels of

job satisfaction expressed by North Carolina vocational agricultural teachers and their perceptions

toward the agricultural education teaching profession. Journal of Agricultural Education, 31(1),

5257. doi: 10.5032/jae.1990.01052

Kennedy, M. M. (2010). Attribution error and the quest for teacher quality. Educational Researcher, 39(8),

591598. doi: 10.3102/0013189X10390804

Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review, 53(1), 2835. doi:

10.1080/00131910120033628

Journal of Agricultural Education

41

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

LeCompte, M. D., & Dworkin, A. G. (1991). Giving up on school: Student dropouts and teacher burnouts.

Newbury Park, CA: Corwin Press.

Leach, C. W., Webster, J. M., Smith, R. H., Kelso, K., Bringham, N., & Garonzik, R. (n.d.). The social

comparison style questionnaire: Assessing tendencies to contrast or assimilate upward and

downward comparisons. Unpublished manuscript.

Lockwood, P., & Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 91103. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.91

Martin, A. B. (2002). Work/family variables influencing the work satisfaction of Tennessee extension

agents. Learning and Satisfaction Symposium 5: Honolulu, HA.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual. Mountain View,

CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Matheny, K. B., Gfroerer, C. A., & Harris, K. (2000). Work stress, burnout, and coping at the turn of the

century: An Adlerian perspective. Journal of Individual Psychology, 56(1), 7487.

Morley, L. (2001). Producing new workers: Quality, equality and employability in higher education.

Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 131138. doi: 10.1080/13538320120060024

Mundt, J. P., & Connors, J. J. (1999). Problems and challenges associated with the first years of teaching

agriculture: A framework for preservice and inservice education. Journal of Agricultural

Education, 40(1), 3848. doi: 10.5032/jae.1999.01038

Myers, B. E., Dyer, J. E., & Washburn, S. G. (2005). Problems facing beginning agriculture teachers.

Journal of Agricultural Education, 46(3), 4755. doi: 10.5032/jae.2005.03047

National FFA Organization. (2003). FFA student handbook. Indianapolis, IN: National FFA Organization.

Newcomb, L. H., Betts, S. I., & Cano, J. (1987). Extent of burnout among teachers of vocational agriculture

in Ohio. Journal of Agricultural Education, 28(1), 2633. doi: 10.5032/jaatea.1987.01017

Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Roberts, T. G., & Dyer, J. E. (2004). Characteristics of effective agriculture teachers. Journal of

Agricultural Education, 45(4), 8295. doi: 10.5032/jae.2004.04082

Robinson, J. S., & Garton, B. L. (2008). College of agriculture graduates perceived levels of job

satisfaction associated with their chosen career field. NACTA Journal, 52(3), 3338.

Robinson, J. S., & Garton, B. L. (2006). Becoming employable: A look at graduates and supervisors

perceptions of the skills needed for employability. NACTA Journal, 51(2), 1926.

Smith, R. H. (2000). Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social

comparisons. Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research (pp. 173200). New York,

NY: Plenum Publishers.

Straquadine, G. S. (1990). Work, is it your drug of choice? The Agricultural Education Magazine, 62(12),

1112.

Journal of Agricultural Education

42

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

Strauss, V. (2002). Everyday problems. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/articles/A61601-2002Oct21.html

Taylor, S. E., & Lobel, M. (1989). Social comparison activity under threat: Downward evaluation and

upward contacts. Psychological Review, 96(4), 569575. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.569

Torres, R. M., Lambert, M. D., & Tummons, J. D. (2010, May). Does the ability to manage time influence

the stress level among beginning secondary agriculture teachers? Paper presented at the meeting of

the American Association for Agricultural Education. Omaha, NE.

Torres, R. M., Lawver, R. G., & Lambert, M. D. (2009). Jobrelated stress among secondary agricultural

education teachers: A comparison study. Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(3), 100 111. doi:

10-5032/jae.2009.03100

Troman, G., & Woods, P. (2001). Primary teachers stress. New York, NY: Routledge/Falmer.

Van Yperen, N. W., Brenninkmeijer. V., & Buunk, A. P. (2006). Peoples responses to upward and

downward social comparisons: The role of individuals effortperformance expectancy. British

Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 519533. doi: 10.1348/014466605X53479

Vaughn, P. R. (1990). Agricultural education: Is it hazardous to your health? The Agricultural Education

Magazine, 62(12), 4.

Walker, W. D., Garton, B. L., & Kitchel, T. J. (2004). Job satisfaction and retention of secondary

agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(2), 2838. doi: 10.5032/jae.2004.02028

Warner, P. D. (1973). A comparative study of three patterns of staffing within the cooperative extension

organization and their association with organizational structure, organizational effectiveness, job

satisfaction, and role conflict. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University: Columbus.

Wedell, D. H. (1994). Contextual contrast in evaluative judgments: A test of pre versus postintegration

models of contrast. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 10071019. doi:

10.1037/00223514.66.6.1007

Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychology Bulletin, 90(2),

245271. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.90.2.245

Wood, J. V., Taylor, S. E., & Lichtman, R. R. (1985). Social comparison adjustment to breast cancer.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 11691183. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.49.5.1169

TRACY KITCHEL is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Education in the Department of Agricultural

Education at the University of Missouri, 126 Gentry Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, kitcheltj@missouri.edu.

AMY R. SMITH is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural Education in the Department of Teaching,

Learning, and Leadership at South Dakota State University, Box 507, Wenona 102, Brookings, SD

57007, amy.r.smith@sdstate.edu.

ANNA L. HENRY is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Education in the Department of Agricultural

Education at the University of Missouri, 127 Gentry Hall, Columbia, MO 65211, ballan@missouri.edu.

Journal of Agricultural Education

43

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Kitchel et al.

Teacher Job Satisfaction

J. SHANE ROBINSON is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Education in the Department of

Agricultural Education, Communications and Leadership at Oklahoma State University, 457 Ag Hall,

Stillwater, OK 740786032, shane.robinson@okstate.edu.

REBECCA G. LAWVER is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural Education in the School of Applied

Sciences, Technology and Education at the Utah State University, 2300 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT,

84321, rebecca.lawver@usu.edu.

TRAVIS D PARK is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Science Education in the Horticulture

Department at Cornell University, 110 Plant Science, Ithaca, NY, 14853, travispark@cornell.edu.

ASHLEY SCHELL is a former Graduate Assistant in the Department of Community and Leadership

Development at the University of Kentucky, 500 Garrigus Building, Lexington, KY 40546,

arschell614@yahoo.com.

Journal of Agricultural Education

44

Volume 53, Number 1, 2012

Você também pode gostar

- Differences in Teacher Efficacy Related To CareerDocumento13 páginasDifferences in Teacher Efficacy Related To CareerÁron KissAinda não há avaliações

- Why I Leaving in TeachingDocumento15 páginasWhy I Leaving in Teachingapi-674364974Ainda não há avaliações

- Job-Related Stress Among Secondary Agricultural Education Teachers: A Comparison StudyDocumento12 páginasJob-Related Stress Among Secondary Agricultural Education Teachers: A Comparison StudyJunk KissAinda não há avaliações

- Job StressDocumento7 páginasJob StressRemar PabalayAinda não há avaliações

- Job Satisfaction of TeachersDocumento13 páginasJob Satisfaction of TeachersJessie L. Labiste Jr.Ainda não há avaliações

- Nazir 1Documento21 páginasNazir 1nazir187Ainda não há avaliações

- Ef Ficacy Beliefs, Job Satisfaction, Stress and Their in Uence On The Occupational Commitment of English-Medium Content Teachers in The Dominican RepublicDocumento25 páginasEf Ficacy Beliefs, Job Satisfaction, Stress and Their in Uence On The Occupational Commitment of English-Medium Content Teachers in The Dominican RepublicEce YaşAinda não há avaliações

- The Influence of Time Management Practices On Job PDFDocumento12 páginasThe Influence of Time Management Practices On Job PDFClarisse AcacioAinda não há avaliações

- EDU AssignmentDocumento23 páginasEDU AssignmentYoNz AliaTiAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Teacher Identity and AttritionDocumento14 páginasUnderstanding Teacher Identity and AttritionDaksina BaasokaAinda não há avaliações

- Rand Rra1108-1Documento25 páginasRand Rra1108-1John TranAinda não há avaliações

- Work Life Balance Among Teachers: An Empirical StudyDocumento11 páginasWork Life Balance Among Teachers: An Empirical StudyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Problems Encountered by Beginning Family and Consumer Sciences TeachersDocumento12 páginasProblems Encountered by Beginning Family and Consumer Sciences TeachersTayo BethelAinda não há avaliações

- Special Education Teachers Under Stress - Evidence From A Greek National Study - Kokkinos2009Documento19 páginasSpecial Education Teachers Under Stress - Evidence From A Greek National Study - Kokkinos2009Apostolis RountisAinda não há avaliações

- Common Stressors and Its Effects To The Teachers of LDocumento7 páginasCommon Stressors and Its Effects To The Teachers of LAlbert Llego100% (1)

- Lokpati PGDHE SynopsisDocumento11 páginasLokpati PGDHE Synopsislokpati0% (1)

- SSRN Id2892494 PDFDocumento17 páginasSSRN Id2892494 PDFLiam PainAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Collective Effi CayDocumento24 páginasTeacher Collective Effi CayAl AAinda não há avaliações

- The EBDteacherstressorsquestionnaireDocumento14 páginasThe EBDteacherstressorsquestionnaireGinalyn QuimsonAinda não há avaliações

- Bottiani Et Al. - 2019 - Teacher Stress and Burnout in Urban Middle SchoolsDocumento16 páginasBottiani Et Al. - 2019 - Teacher Stress and Burnout in Urban Middle SchoolskehanAinda não há avaliações

- Watt&Richardson Article JLI2008Documento21 páginasWatt&Richardson Article JLI2008eyan1967Ainda não há avaliações

- Building Ahrentzen 8Documento24 páginasBuilding Ahrentzen 86111801101Ainda não há avaliações

- Newly Qualified Teachers' Work Engagement and Teacher Efficacy Influences On Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and The Intention To QuitDocumento12 páginasNewly Qualified Teachers' Work Engagement and Teacher Efficacy Influences On Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and The Intention To QuitAlice ChenAinda não há avaliações

- BOGLER & SOMECH (2004) - Influence of Teacher Empowerment On Teachers' Organizational Commitment, Professional Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in SchoolsDocumento13 páginasBOGLER & SOMECH (2004) - Influence of Teacher Empowerment On Teachers' Organizational Commitment, Professional Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in SchoolsCarlos Araneda-UrrutiaAinda não há avaliações

- Educación y Ciencia v3-n41-2013Documento13 páginasEducación y Ciencia v3-n41-2013Deneb Magaña MedinaAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Retention Teacher Characteristics School Characteristics Organizational Characteristics and Teacher Efficacy-Gail D. Hughes-KuantitatifDocumento12 páginasTeacher Retention Teacher Characteristics School Characteristics Organizational Characteristics and Teacher Efficacy-Gail D. Hughes-KuantitatifkerjauntuktuhanAinda não há avaliações

- Teachers' Job Satisfaction and Teaching Commitment: A New Normal PerspectiveDocumento8 páginasTeachers' Job Satisfaction and Teaching Commitment: A New Normal PerspectivePsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Teachers' Psychological Needs Link Social Pressure and Teaching StyleDocumento22 páginasTeachers' Psychological Needs Link Social Pressure and Teaching StyleAFRIDATUS SAFIRAAinda não há avaliações

- Job Satisfaction-Intro To FinalDocumento23 páginasJob Satisfaction-Intro To Finalmharlit cagaananAinda não há avaliações

- Job SatisfactionDocumento11 páginasJob SatisfactionlokpatiAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0742051X20314128 MainDocumento14 páginas1 s2.0 S0742051X20314128 MainAlícia NascimentoAinda não há avaliações

- A Gender Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Job Satisfier Factors, and Job Dissatisfier Factors of Agricultural Education TeachersDocumento7 páginasA Gender Analysis of Job Satisfaction, Job Satisfier Factors, and Job Dissatisfier Factors of Agricultural Education TeachersAik MusafirAinda não há avaliações

- Occupational Stress and Professional Burnout in TeachersDocumento7 páginasOccupational Stress and Professional Burnout in TeachersAnonymous N9bM1y6Hhj100% (1)

- Impact of Work Life Balance of Teachers During Covid 19 Pandemic On Teacher Demand and SupplyDocumento10 páginasImpact of Work Life Balance of Teachers During Covid 19 Pandemic On Teacher Demand and SupplyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpAinda não há avaliações

- Amidst The COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Affecting Teacher's Job Satisfaction in Public Secondary SchoolDocumento10 páginasAmidst The COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Affecting Teacher's Job Satisfaction in Public Secondary SchoolPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalAinda não há avaliações

- SP Makale Tam MetinDocumento17 páginasSP Makale Tam Metinhilal.buyukgozeAinda não há avaliações

- Determinants of Teacher StressDocumento11 páginasDeterminants of Teacher StressGoropadAinda não há avaliações

- Should I Stay or Should I Go? Understanding Teacher Motivation, Job Satisfaction, and Perceptions of Retention Among Arizona TeachersDocumento12 páginasShould I Stay or Should I Go? Understanding Teacher Motivation, Job Satisfaction, and Perceptions of Retention Among Arizona TeachersNicahAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Stress and Wellbeing Literature Review: ©daniela Falecki 2015Documento8 páginasTeacher Stress and Wellbeing Literature Review: ©daniela Falecki 2015Eenee ChultemjamtsAinda não há avaliações

- Maestros AgricultoresDocumento5 páginasMaestros AgricultoresAmelie RojasAinda não há avaliações

- Change-Linked Work-Related Stress in British Teachers: Marie Brown, Sue Ralph and Ivy BremberDocumento12 páginasChange-Linked Work-Related Stress in British Teachers: Marie Brown, Sue Ralph and Ivy BremberOana ElenaAinda não há avaliações

- Continuing Validation of The Teaching Autonomy ScaleDocumento9 páginasContinuing Validation of The Teaching Autonomy ScaleMr KulogluAinda não há avaliações

- Manuscript DefDocumento34 páginasManuscript DefNOR ADLI HAKIM BIN ZAKARIAAinda não há avaliações

- Teachers' SES relationship with morale & performanceDocumento5 páginasTeachers' SES relationship with morale & performanceShaguolo O. JosephAinda não há avaliações

- Teachers' Job SatisfactionDocumento19 páginasTeachers' Job Satisfactionmancheman2011Ainda não há avaliações

- ED461649Documento23 páginasED461649Shauna NicholasAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Diversity: Do Male and Female Teachers Have Different Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction?Documento17 páginasTeacher Diversity: Do Male and Female Teachers Have Different Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction?lucianaeuAinda não há avaliações

- BurnoutDocumento22 páginasBurnoutCarolina Méndez SandovalAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter I To IVDocumento63 páginasChapter I To IVREX ABAYONAinda não há avaliações

- Adapted Physical Education Teachers Job SatisfactionDocumento21 páginasAdapted Physical Education Teachers Job Satisfactionmiquelgrauh24Ainda não há avaliações

- Early Childhood Teachers Psychological Well Being Exploring Potential Predictors of Depression Stress and Emotional ExhaustionDocumento18 páginasEarly Childhood Teachers Psychological Well Being Exploring Potential Predictors of Depression Stress and Emotional ExhaustionAhmed QlhamdAinda não há avaliações

- Job Stress and Burnout Among Lecturers: Personality and Social Support As ModeratorsDocumento12 páginasJob Stress and Burnout Among Lecturers: Personality and Social Support As ModeratorsElisabeta Simon UngureanuAinda não há avaliações

- Ej 1077456Documento9 páginasEj 1077456zafarghazaliAinda não há avaliações

- SE Teachers - Coping StrategiesDocumento26 páginasSE Teachers - Coping StrategiesGoropadAinda não há avaliações

- Section 5.4 Working Conditions, Stress And: Learning: Teachers and Other WorkersDocumento35 páginasSection 5.4 Working Conditions, Stress And: Learning: Teachers and Other WorkersJunk KissAinda não há avaliações

- SOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTNo EverandSOCIAL WORK ISSUES: STRESS, THE TEA PARTY ROE VERSUS WADE AND EMPOWERMENTAinda não há avaliações

- Teacher Wellbeing During COVID-19 (Pre-Print 21 Jan 2021)Documento32 páginasTeacher Wellbeing During COVID-19 (Pre-Print 21 Jan 2021)Edl ZsuzsiAinda não há avaliações

- Dimensions of Teachers' Work-Life Balance and School Commitment - A. D. MarmolDocumento11 páginasDimensions of Teachers' Work-Life Balance and School Commitment - A. D. MarmolIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)100% (2)

- Knobloch Etal 48 3 25-36Documento12 páginasKnobloch Etal 48 3 25-36ozapnagneblucAinda não há avaliações

- What Makes Teachers Well? A Mixed-Methods Study of Special Education Teacher Well-BeingDocumento26 páginasWhat Makes Teachers Well? A Mixed-Methods Study of Special Education Teacher Well-Beingprimrose.bulaclacAinda não há avaliações

- Greeting Phrases ESL LessonDocumento12 páginasGreeting Phrases ESL LessonNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- HSE Manual Rev00Documento328 páginasHSE Manual Rev00Nikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Providing Misleading Info A Year LaterDocumento13 páginasProviding Misleading Info A Year LaterNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Direct Democracy For Transition CountriesDocumento39 páginasDirect Democracy For Transition CountriesNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Coping With Sales Call Anxiety The Role of Sale PerseveranceDocumento17 páginasCoping With Sales Call Anxiety The Role of Sale PerseveranceNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Lista Alfabetica A Tuturor Teoriilor PsihologiceDocumento7 páginasLista Alfabetica A Tuturor Teoriilor PsihologiceNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Measuring Health Worker Motivation PDFDocumento29 páginasMeasuring Health Worker Motivation PDFNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Student Attrition, Retention, and PersistenceDocumento26 páginasStudent Attrition, Retention, and PersistenceNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Cross-Cultural Study of Task Persistence of Young ChildrenDocumento10 páginasCross-Cultural Study of Task Persistence of Young ChildrenNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Grit JPSP PDFDocumento15 páginasGrit JPSP PDF'Mabel CardenasAinda não há avaliações

- 7.the Impact of Physical and Discursive Anonymity On Group MembersDocumento31 páginas7.the Impact of Physical and Discursive Anonymity On Group MembersNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Contenido Curso Apa Sobre VBG PDFDocumento87 páginasContenido Curso Apa Sobre VBG PDF110780Ainda não há avaliações

- The Role of Emotions in MarketingDocumento23 páginasThe Role of Emotions in Marketingluizamj100% (5)

- Affect IntensityDocumento11 páginasAffect IntensityNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- A Competency-Based Art Therapy Approach For Improving The Self-EsDocumento155 páginasA Competency-Based Art Therapy Approach For Improving The Self-EsNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- LogopedieDocumento66 páginasLogopedieNikoleta Hirlea100% (1)

- Incapacity PsychologistDocumento186 páginasIncapacity PsychologistNASC8Ainda não há avaliações

- Oua de PasteDocumento42 páginasOua de PasteNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Perceived Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction AmongDocumento6 páginasPerceived Emotional Intelligence and Life Satisfaction AmongNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout Among Special Education TeachersDocumento48 páginasBurnout Among Special Education TeachersNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Das Scoring PDFDocumento2 páginasDas Scoring PDFNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Ies RDocumento3 páginasIes RNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout Si Satisfactia MaritalaDocumento14 páginasBurnout Si Satisfactia MaritalaNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- A Meta-Analytic Review of Work-Family Conflict and Its AntecedentsDocumento30 páginasA Meta-Analytic Review of Work-Family Conflict and Its AntecedentsIoan Dorin100% (1)

- Burnout Si Satisfactia MaritalaDocumento14 páginasBurnout Si Satisfactia MaritalaNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Factors That Influence Burnout InventoryDocumento12 páginas3 Factors That Influence Burnout InventoryNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Regret ComparisonDocumento9 páginas1 Regret ComparisonNikoleta HirleaAinda não há avaliações

- Gender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work ConflictsDocumento17 páginasGender Difference: Work and Family Conflicts and Family-Work ConflictsAmbreen AtaAinda não há avaliações

- Stres OcupationalDocumento23 páginasStres OcupationalLaura Florea100% (3)

- Cellular Basis of HeredityDocumento12 páginasCellular Basis of HeredityLadyvirdi CarbonellAinda não há avaliações

- Human Capital FormationDocumento9 páginasHuman Capital Formationtannu singh67% (6)

- 07 Chapter2Documento16 páginas07 Chapter2Jigar JaniAinda não há avaliações

- Vturn-NP16 NP20Documento12 páginasVturn-NP16 NP20José Adalberto Caraballo Lorenzo0% (1)

- MR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWDocumento1 páginaMR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWRafik FafikAinda não há avaliações

- Soal Upk B Inggris PKBM WinaDocumento11 páginasSoal Upk B Inggris PKBM WinaCuman MitosAinda não há avaliações

- Đề Thi Thử THPT 2021 - Tiếng Anh - GV Vũ Thị Mai Phương - Đề 13 - Có Lời GiảiDocumento17 páginasĐề Thi Thử THPT 2021 - Tiếng Anh - GV Vũ Thị Mai Phương - Đề 13 - Có Lời GiảiHanh YenAinda não há avaliações

- Goals Editable PDFDocumento140 páginasGoals Editable PDFManuel Ascanio67% (3)

- PHAR342 Answer Key 5Documento4 páginasPHAR342 Answer Key 5hanif pangestuAinda não há avaliações

- Grade Eleven Test 2019 Social StudiesDocumento6 páginasGrade Eleven Test 2019 Social StudiesClair VickerieAinda não há avaliações

- The Girls Center: 2023 Workout CalendarDocumento17 páginasThe Girls Center: 2023 Workout Calendark4270621Ainda não há avaliações

- Elem. Reading PracticeDocumento10 páginasElem. Reading PracticeElissa Janquil RussellAinda não há avaliações

- TDS Versimax HD4 15W40Documento1 páginaTDS Versimax HD4 15W40Amaraa DAinda não há avaliações

- Jairo Garzon 1016001932 G900003 1580 Task4Documento12 páginasJairo Garzon 1016001932 G900003 1580 Task4Jairo Garzon santanaAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial 7: Electromagnetic Induction MARCH 2015: Phy 150 (Electricity and Magnetism)Documento3 páginasTutorial 7: Electromagnetic Induction MARCH 2015: Phy 150 (Electricity and Magnetism)NOR SYAZLIANA ROS AZAHARAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI Chart 2014 EditionDocumento80 páginasIMCI Chart 2014 EditionHarold DiasanaAinda não há avaliações

- December - Cost of Goods Sold (Journal)Documento14 páginasDecember - Cost of Goods Sold (Journal)kuro hanabusaAinda não há avaliações

- Circulatory System Packet BDocumento5 páginasCirculatory System Packet BLouise SalvadorAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Distinction From ICD Pre-DSM-1 (1840-1949)Documento25 páginasDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Distinction From ICD Pre-DSM-1 (1840-1949)Unggul YudhaAinda não há avaliações

- Biology (Paper I)Documento6 páginasBiology (Paper I)AH 78Ainda não há avaliações

- Ucg200 12Documento3 páginasUcg200 12ArielAinda não há avaliações

- Ic Audio Mantao TEA2261Documento34 páginasIc Audio Mantao TEA2261EarnestAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Colmac DX Ammonia Piping Handbook 4th EdDocumento64 páginas1 Colmac DX Ammonia Piping Handbook 4th EdAlbertoAinda não há avaliações

- Kertas Trial English Smka & Sabk K1 Set 2 2021Documento17 páginasKertas Trial English Smka & Sabk K1 Set 2 2021Genius UnikAinda não há avaliações

- Ethamem-G1: Turn-Key Distillery Plant Enhancement With High Efficiency and Low Opex Ethamem TechonologyDocumento25 páginasEthamem-G1: Turn-Key Distillery Plant Enhancement With High Efficiency and Low Opex Ethamem TechonologyNikhilAinda não há avaliações

- Indonesia Organic Farming 2011 - IndonesiaDOCDocumento18 páginasIndonesia Organic Farming 2011 - IndonesiaDOCJamal BakarAinda não há avaliações

- VIDEO 2 - Thì hiện tại tiếp diễn và hiện tại hoàn thànhDocumento3 páginasVIDEO 2 - Thì hiện tại tiếp diễn và hiện tại hoàn thànhÝ Nguyễn NhưAinda não há avaliações

- Magnetic FieldDocumento19 páginasMagnetic FieldNitinSrivastava100% (2)

- Jounce Therapeutics Company Events and Start DatesDocumento48 páginasJounce Therapeutics Company Events and Start DatesEquity NestAinda não há avaliações

- Vaginal Examinations in Labour GuidelineDocumento2 páginasVaginal Examinations in Labour GuidelinePooneethawathi Santran100% (1)