Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Music Therapy

Enviado por

Alyssa LeonesDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Music Therapy

Enviado por

Alyssa LeonesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

research article

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(1) 2008, pp. 30-40.

The Day the Music Died

A Pilot Study on Music and Depression in a Nursing Home

Audun Myskja & Pl G. Nord

Abstract

Background: The nursing home Vlerengen bo- og servicesenter in Oslo, Norway, a long-term

institution with 84 residents, has continually had regular music therapy activities with a music therapist

in full-time employment since 1999. The institution was without music therapy services during the fall

of 2003. Method: At the end of the period without a music therapist, measurement of depression level

by the use of Montgomery Aasberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was conducted on residents

(n=72). Two months after music therapy services had been resumed with music therapy groups twice

a week in each ward and individualized services other days, a new measurement of depression level

of all residents was conducted. Results: Depression rating show a significant fall in the music therapy

condition, compared with the no music therapy condition in a crossover design: MADRS 20.4 on an

average in the no music condition, 12.2 on an average in the music condition (p < .05). Staff at the

institution was stable, and there were no significant changes in medication. Conclusion: A significant

reduction in the average level of depression in a nursing home when music therapy services are

resumed warrants recommendation for a larger controlled follow-up study.

Keywords: Elderly, nursing homes, music therapy, singing, depression, geriatrics.

Introduction

Depression in the Elderly

The elderly segment of the population is growing

worldwide. Depression is projected to become the

leading cause of disability and the second leading

contributor to the global burden of disease by the

year 2020 (WHO, 2007). Major depressive illness

is present in about 5.7% of US residents aged 65

years, whereas clinically significant nonmajor or

subsyndromal depression affects approximately

15 % of the ambulatory elderly (VanItalie, 2005).

30

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

AUDUN MYSKJA, MD, Certified specialist in

General medicine, Fellow in Neurological music

therapy. Project leader, Red Cross Competence

Center for Palliative Care, Bergen. Correspondence

address: Idrettsv. 20, 1400 Ski, Norway.

Email info@livshjelp.no

PL G. NORD, MD, MPH, Pfizer AS, P.O. Box 3,

1324 Lysaker, Norway.

Email: paal.g.nord@pfizer.com

Conflict of Interests: Pl G. Nord has position as

medical adviser for Pfizer in Norway.

The Day the Music Died

In nursing homes, the prevalence of depressive

disorders among nursing home residents is high;

depression recognition is relatively low, with only

37%-45% of cases diagnosed by psychiatrists

recognized as depressed by staff (Teresi, 1999).

A Norwegian multicentre study of depression

and dementia in nursing home residents showed

an average prevalence of depression of around 40

% (Selbk, 2007). The coexistence of medical,

neurodegenerative, and other psychiatric disorders

are confounding factors, making diagnosis and

treatment of depression in old age a challenging

task (Weyerer, Mann & Ames, 1995).

Causes of depression are complex, compared

to depression in the younger segment of the

population. Losses and defective adaptation

to losses play a larger causative role, as do

health problems, like heart disease, cancer,

and neurological disorders, which often are

accompanied by depression. WHO reports that

depression is one of the major causes of disability

among the aged, the incidence is rising, and it is

calculated that depression will be the primary

cause of disability and one of the two largest

disease groups in the elderly by the year 2020

(WHO, 2006). Antidepressant drugs are the

major treatment strategy for depression. This

presents challenges in medical treatment of the

elderly, since drug treatment for depression is

more difficult to administer in this population

segment, side effects and interactions being

common (Mottram, Wilson & Strobl, 2006).

Another important aspect is that depression in the

elderly takes many forms and often grows as a

vicious cycle, developing in the face of multiple

losses relationships, position in society, health,

sensory function, and other important functions.

This is often compounded by sleep disturbances,

inactivity, and lack of adequate stimulation. There

is therefore a growing interest in supplementary

treatment strategies for depression in the elderly.

Music has special potential in nursing homes,

given the ability of music to function as a

language that to a certain extent can replace

verbal language in the cognitively impaired and

provide meaningful stimulation (Opie, 1999).

The clinical and precise use of music therapy can

address the different components of the vicious

cycle that often accompanies depression in the

terminal stages of life (Hilliard, 2005). In this

sense, music therapy can in many situations have

an advantage over pharmaceutical treatment, since

it can address many of the components creating

the vicious cycle of depression, both restoring

a sense of community with group singing,

giving adequate sensory stimulating, furthering

movement, evoking positive and therapeutic

memory, and increasing empowerment and the

use of formally acquired skills (Brotons & Marti,

2003).

Music as a Supplementary Treatment.

Through the ages music has had a natural role

in treatment in different cultures. In Western

culture music was an integral part of treatment

of complaints in the Greek culture and the

Middle Ages, but became regarded more as a

cultural expression with little specific therapeutic

potential with the advent of modern medicine

in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the late 20th

century the role of music in treatment became

strengthened with the advent of music therapy

as a defined profession with a growing research

base after World War II. Research has found

evidence for a variety of psychophysiological

effects of music, and neuroscientific research is

building an evidence base for the use of music

(Thaut, 2005).

Effect size is a statistical tool devised specially

to evaluate therapies based on psychotherapy

and other relational methods (Cohen, 1988), and

the use of effect sizes has been found to be a

valuable tool for comparing different therapeutic

modalities (Gold, 2004).

A meta-analysis of music therapy literature

has shown active music therapy to be more

effective than prerecorded music, although there

were found only 16 studies of live music therapy

conducted by music therapists, compared to 216

studies using prerecorded music as intervention.

A comparative analysis of effect sizes showed

that live music therapy had a significantly higher

effect size than prerecorded music (Standley,

2000). These are important considerations when

deciding on whether to give priority to music

therapy in a situation with scarce funding and

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

31

Audun Myskja & Pl G. Nord

shortage of skilled nursing staff (Dileo, Bradt,

Murphy, Keith & Zanders, 2002).

Music Therapy and Depression in the Elderly

The therapeutic use of music in the elderly does

not have less effect or higher interaction problems

than treatment with music in younger age

groups. Music is well tolerated, and experienced

positively by a majority of patients (Wigram,

2002). A large part of the elderly population has

problems with expressing emotions or expressing

through speech and language. In these cases

music may have a particular potential. Music has

shown particular promise as supportive treatment

of depression in the elderly (Hsu & Lai, 2004).

We have a general lack of studies indicating

which types of music activities are the most

effective for depressed nursing home residents,

though music therapy studies have shown

that active music therapy is more effective for

emotional variables than passive music therapy

(Montello & Coons, 1999). Music therapists

have devised tailored programs for depressed

elderly persons (Hanser, 1990). Investigations

have indicated positive effects of such strategies

(Hanser & Thompson, 1994). Literature reviews

have indicated promising results of music therapy

as supplementary treatment of depression in the

elderly (Brotons, 2000), although solid evidence

still needs to be established (Maratos & Gold,

2003).

The Reason for the Present Investigation

Vlerengen bo- og servicesenter is a nursing home

in Oslo with 84 long-term inhabitants, residing in

three wards. Ward 1 is a somatic ward with a high

degree of functional disability and a high average

number of somatic diseases and classifiable

diagnosis in the residents. Ward 2 has a mixed

population with a high incidence of dementia and

somatic diseases. Ward 3 is a dementia ward with

24 residents divided into four groups of six.

The institution has placed high emphasis on

cultural and stimulating activities, and since

1999 had employed a professional in a full time

position to provide music therapy services. The

professional in question did not have formal

music therapy education, but worked with active

32

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

music techniques under guidance from a trained

music therapist, and will therefore in this paper

be termed music therapy aide.

The music therapy aide had developed music

therapy techniques that were experienced as

highly effective by the trained staff (Myskja,

2006). There were also concerts, dances, and

individualized sessions. Measurement of wellbeing for a selected group of residents with

numerical rating scales (NRS) indicated a

significant increase in well-being in the majority

of residents participating in the music sessions,

compared to other activities not involving music.

There were thus several indications that the music

therapy intervention was beneficial, making it

natural to investigate what the benefit may be,

and for what symptoms.

A natural experiment arose when the music

therapist was absent for a period of 11 weeks. The

music therapy aide at the institution had during

the preceding year been present all year round,

having had only short absences of one week at a

time. When he had a three month leave of absence,

several nurses started reporting after a few weeks

of his absence that a large number of residents

seemed in tangibly lower spirits. They attributed

this observation to the absence of the usual

music activity. This possible effect was reported

independently in all three wards in the institution.

Even staff members with no particular affinity

to the use of music for therapeutic purposes

described that they perceived causal link between

the absence of the music groups and the increasing

depressive tendency they saw with several of the

residents. Many staff members suggested that it

would be important to look more closely at this

observation to investigate whether the observed

increase in depression also was measurable. This

led to a decision to supplement interviews with

trained staff with the use of a validated instrument

to measure depression levels.

The aim of the present study is to explore

possible changes in symptoms of depression

among the inhabitants associated with the absence

of regular music sessions. The two different

conditions are termed no music and music

conditions, not because there was an absolute

absence of music when the institution was without

The Day the Music Died

music therapy services. There were, however, no

apparent changes in other sources of music or

other stimulation to account for differences in the

no music and music conditions.

Method

Study Design

The study was designed as a pre/post measurement

of depression levels in the included residents

at the institution (n = 72). The measurement of

depression levels in the no music condition was

performed during the last week of the music

therapy aides 11-week leave of absence. After 6

weeks of resumed music activity, measurement of

depression levels in the included residents (n = 63)

was measured as the music condition parameter.

The Nature of the Intervention

Twice a week music sessions (average duration

45 minutes each) were conducted in each of the

three wards of the nursing home. The music

therapy aide led the singing of familiar and

preferred songs, accompanying the songs on the

piano. The sequences of the songs were based on

charting of music preferences both for the group

and for individuals. Music preference was found

through a method of systematic investigation

based on questionnaires and the use of preference

CDs, making the process of song selection

more precise and specific. The repertoire of the

music sessions was developed gradually from

the preference principles. The music therapy

aide sang and played the piano with a strong

chordal style songs and music pieces pooled

from results of preference charting to create a

repertoire that focused on the four sequences

outlined in the work of Danish music therapist

Hanne Ridder (2004, 2005):

Focus attention

Regulate arousal

Dialogue

Conclusion.

Each of the four main sequences charted by

Hanne Ridder for patients with dementia were

used in the planning process:

1. Focus attention. The stage setting and

creating of initial framework was normally

established by an inviting rhythmic song,

not too hard or harsh, along the lines of

welcome songs. One Norwegian song often

used had a textual theme roughly translated

as: Lift your anchor, get the motor

running, we are going together on a great

adventure.

2. Regulate arousal. Regulation of attention

and activation was attended by creating a

dialectic between brisk, danceable tunes

and slower, well-known tunes that were

instantly recognized, for instance, well

loved songs from childhood. Thus we

mainly succeeded in creating an alert

response that was able to engage each of

the individual group members, without

overstimulating or creating activation

through using solely faster songs.

3. Dialogue. In this deepening part of the

session, we used songs that had shown

the ability to communicate meaningful

memories and deep issues for the members,

evoking both awareness of the group,

mental clarity, and constructive emotional

responses. Examples of this were local

songs from the regions of different

participants, who had often moved from

rural areas into Oslo in youth or early

adulthood. We used patriotic songs for male

residents with defining memories from

World War II and well-loved hymns for

participants with strong religious beliefs.

At the same time, we tried to see to it that

as many participants as possible were

given meaningful themes individually,

in order to feel included in the group

activity. We tried to accomplish this by not

concentrating on a few categories solely,

but trying to include a broad repertoire,

which would not be offending to any

group members. For instance, some had

a history in marching bands and loved

the marching songs, but we tried not to

include too many, as this would be offputting to some other group members.

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

33

Audun Myskja & Pl G. Nord

Gender

Mean age

Female

51 (71 %)

87.5 (68.2-95.8)

Male

21 (29 %)

80.9 (57.7-93.2)

All

86.6

Alzheimers

Dementia (AD)

Multi-infarction

Dementia (MID)

FrontoTemporal

Dementia (FTD)

Other

Of all

53 of 72

(74%)

33 of 72 (46 %)

15 of 72 (21 %)

2 of 72 (3 %)

3 of 72 (4 %)

Of those

diagnosed

with

Dementia

33 of 53 (62 %)

15 of 53 (28 %)

2 of 53 (4 %)

3 of 53 (6 %)

Dementia

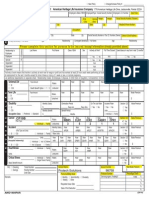

Table 1: Distribution of age, gender, and prevalence and types of dementia at the institution.

4. Conclusion. We tried, through trial and

error, to find songs that could define the

groups time together and create a feeling

of completion. When the group needed to

strengthen a sense of fellowship, we often

used the Norwegian translation of Auld

Lang Syne, whereas Anchors Aweigh

was used at times where we wished to let

the sessions end on a brisk and encouraging

note.

Song programmes were developed gradually

through observation of responses of the

participants, especially through staff, who were

present in every session and observed reactions

of the participants according to observational

guidelines taken from the validated observational

method Dementia care mapping (Brooker,

2004). The initial choice of repertoire focused on

familiar songs, encouraging participation in song

and dance to facilitate expression and mobilize

resources in the form of previous skills and

positive memories (Small & Gutman, 2001).

All residents were encouraged to participate,

and 72 of 84 residents participated regularly

at the time of the study. The non-participants

were analyzed for possible reasons for nonparticipation through observation and interviews.

Three main reasons were found: Physical

infirmity (6 persons), alcoholic dementia (4

persons), personality factors (3 persons).

34

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

Inclusion Criteria

The following criteria of inclusion were chosen:

All long-term residents at Vlerengen boog servicesenter.

Exclusion criteria were:

In hospital or in other institutions at the

time of inclusion.

Short-term placement.

In the terminal stage of life.

72 of 84 residents were thus included in the first

measurements, 5 residents were hospitalized or

in gerontopsychiatric units or other institutions,

2 residents were in short-term placement, and 5

were in terminal stages and could not participate

in the music sessions. Sixty-three could be

included in the second round of measurements,

after the same criteria. Six residents had died,

three had been discharged to hospital or other

institutions.

The distribution of mean age, gender, and

dementia diagnosis of the 72 residents who were

included is shown in Table 1.

Diagnostic data were incomplete for 13 of the

residents. The data for these residents are based

on testing for cognitive failure by the instruments

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), performed by

the occupational therapist at the institution, who

The Day the Music Died

n

Ward 1

M (SD)

Ward 2

M (SD)

Ward 3

M (SD)

Ward 1,2,3

combined

No music

27

18.6 (5.7)

12

27.5 (3.8)

24

21.7 (5.8)

63

20.4 (6.2)

Music

27

11.1 (2.7)

12

15.5 (3.6)

24

12.7 (3.2)

63

12.2 (3.3)

Table 2: Mean MADRS score in Ward 1, 2 and 3, in No Music and Music condition. P-value for the

paired t-test of the difference mean is <0.001

emotional and behaviour states of patients the

project leader had taken advanced education in

dementia care mapping, and had educated staff

in observational criteria to uncover depressive

reactions. Staff members involved in this

study had been trained through role plays and

discussion of cases to observe and evaluate mood

states as precisely and objectively as possible.

The measurement was conducted by interviews,

taking place in the same location at two fixed

Method of Measurement Practical Aspects

times during a 7-day period, 11 AM and 4 PM.

The measurements by Montgomery Aasberg Where there was doubt on the MADRS rating

Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) in the no we observed the resident after the observational

music condition were conducted the last week criteria outlined in the validated rating method

of October 2003, in the last week of the music Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) to find

therapists leave of absence. The second part was consensus on the rating (Beavis, Simpsons &

conducted in the last week of January 2004, two Graham, 2002).

months after the music therapist had resumed

The level of depression measured by MADRS

his work. To increase precise evaluation of the was conducted by proxy, in each case choosing

the nurse leading the group and the primary nurse

Mean MADRS Score and 95% CI in the

with the closest contact to the resident. The two

No music and in the Music condition

main nurses involved with each patient giving

their ratings independently, blinded to the rating

2 5 ,0 0

results of the other. The aim of the investigation

2 0 ,0 0

was not divulged, but presented as a general

investigation of the level of cognitive decline,

1 5 ,0 0

agitation and depression in the residents in the

(N = 63)

institutions. Where possible, the same nurses were

1 0 ,0 0

used both in evaluation of depression through

5 ,0 0

MADRS in the no-music condition and in the

music condition. Where there was consensus

0 ,0 0

within one digit the highest number was taken.

No M usic

M usic

If the diversion was two digits or more, the

patient was re-evaluated until the correct figure

arose through discussion of each question in the

Figure 1: MADRS scores in the no music condition MADRS scale, in order to make measurements

and the music condition: Average values for all as precise as possible.

included patients from the three wards combined.

The results were evaluated statistically through

MADRS Score

had special training in using these instruments.

Is this population representative of a nursing

home population? There are no special conditions

distinguishing the institution in question from

comparable institutions in other regions of Norway

(Selbk, 2007). The demographic data show little

difference from nursing home residents studied in

other investigations, and are comparable to data

from other countries (Ness, 2004).

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

35

Audun Myskja & Pl G. Nord

Degree of

participation

No. of residents in

category

MADRS no music

condition

M (SD)

MADRS music

condition

M (SD)

Mean

change

10

14.00 (3.89)

13.80 (3.71)

-0.20

1

2

3

2

11

40

24.00 (16.97)

17.91 (4.35)

22.45 (5.37)

11.00 (1.41)

12.55 (2.07)

11.85 (3.44)

-13.00

-5.36

-10.60

Table 3: The relation between participation in the music therapy groups and MADRS values.

simple linear model descriptive analysis.

A descriptive analysis for each subgroup is shown

in Table 3.

To examine the relationship between the

degree of participation in music therapy and

the degree of symptom change statistically, we

calculated a linear model with the change in

symptom scores as the response variable, and

participation, pre-test score, and the interaction

of the two as predictor variables.

The result of this linear model, as shown in

Table 4, indicates that participation predicted

change (p < .05). The model explained 79% of

the total variance.

We thus found a tendency towards larger

improvement in the groups with high levels

of participation. We also found that the most

deeply depressed individuals had a lower level of

participation in the music therapy sessions.

Results

The initial measurements following 11 weeks of

the no music condition gave average MADRS

levels in Ward 1, 2, and 3 as shown in the No

music figures in Table 2.

The results of MADRS measurements in Ward

1, 2, and 3, conducted following the resumed

music therapy, are shown in the Music figures

in Table 2: Measurement results ranged from 6

to 46, higher values indicating higher level of

depression.

Frequency analysis including standard deviation

and confidence intervals showed p < .05, i.e., a

highly significant reduction of depression in the

music condition.

The included residents were rated

independently by the ward nurses for degree of

participation in the music therapy groups, shown

in Table 3:

Discussion

Choice of Design

We wished to look at the general impact the

music therapy session might have on the mood

state of the population of the nursing home. A

randomised controlled trial design was evaluated

3 always or nearly always present

2 usually present

1 sometimes present

0 never or almost never present

(Intercept)

Score1

Participation

Score1 x Participation

Estimate

SE

10.75

-0.79

-2.22

0.05

2.31

0.14

1.02

0.06

4.66

-5.54

-2.18

0.85

< .001 ***

< .001 ***

< .05 *

0.40

Table 4: Linear model of participation in music therapy and symptom change.

36

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

The Day the Music Died

to be both impracticable and debatable from an

ethical viewpoint: The residents had voted with

their feet as to whether they wished to take part

or not. To see if randomisation was still feasible,

we conducted a pilot study with a small group

(n = 8), to see whether it would be practically

possible to carry out randomisation. A resident

who was included in the trial usually became

agitated by music, ran out of the room, and could

not be contained, whereas a resident who was

excluded by randomisation but loved the music

groups, heard the music and tried to get in to the

music room during a session.

Therefore, a pilot study involving all the

residents at the institution was found to be best

suited, on a combined evaluation of practicability,

completeness, the study question, and ethical

aspects. Each resident at the institution who

could be included, served as his/her own control

and was evaluated both in the no music condition

and in the music condition.

Choice of Measuring Instrument

After deciding to measure depression levels

of the residents at the institution, the choice of

instrument was challenging. The project leader

had extensive experience with MontgomeryAasberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),

from clinical work and research in general

practice, psychiatry, and gerontopsychiatry,

and the project supervisors advised that this

instrument would be adequate to give answers of

value. In the literature, we found that MADRS

had been used as a tool to evaluate depression in

elderly patients suffering from dementia (Rao &

Lyketsos, 2000). MADRS as diagnostic tool has

been found to have sufficient internal consistency,

validity, and reliability in rating this patient

group in a recent study indicating that MADRS

may have reliability on a level with Cornell Scale

for Depression in Dementia, which is regarded

as state-of-the-art tool to evaluate depression in

dementia (Muller-Thomsen, Arlt, Mann, Mass &

Ganzer, 2005).

The Change in Depression Levels

The reduction in depression after the music

therapist had resumed his activity is statistically

significant, and warrants closer investigation.

There are several factors within the study situation

that need consideration:

The depression rates in the initial no music

condition were different in the three wards,

highest in ward 2, a mixed ward with both somatic

complaints and dementia. The ratings were lowest

in ward 1, a somatic ward, whereas ward 3, the

dementia ward, had ratings in between the two.

The reasons for this difference may be complex:

One may presume that the somatic ward has

patients with more somatic complaints and thus

less psychiatric complaints, like depression. This

is, however, an assumption, and we had no clear

data to indicate that this is so. We know that

dementia and depression often accompany each

other and form a vicious cycle. There was no

significant difference in the use of antidepressant

drugs in the three wards.

From observation and interviews we found

that the most likely account of the difference in

depression level between the three wards was

the working conditions of staff. Ward 2 had had

instability and discontent in staff, several different

leaders the preceding years, and was only just

beginning to enter a more stable situation. Ward

1 and 3 had more stable leadership and personnel

situations, but the dementia ward had several

challenging cases with preexisting psychiatric

illness compounding the clinical picture of

dementia.

There was also a correlation between

participation in music groups and improvement

in MADRS measurements. The lack of adequate

stimulation of elderly residents in nursing homes

does not rule out general stimulating effects. It

must, however, be noted that the music therapy

sessions were replaced with general activities

in the absence period of the music therapist,

activities like card games presumed to be both

enjoyable and stimulating to the residents. At

the present institution, the benefit of the music

therapy sessions was obvious to staff, as expressed

in semistructured interviews conducted during

the project period. The interviews particularly

emphasize the effect of the music therapy sessions

on the general mood state, both of individuals and

at the institution as a whole (Myskja, 2006).

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

37

Audun Myskja & Pl G. Nord

Possible Sources of Bias

In this study, we initially tried to use MADRS

to interview the residents. However, we found it

impossible to carry through the ratings, due to the

high number of residents who had dementia and

therefore were not able to comprehend and reply

adequately to the questions. We therefore used

independent evaluations by two experienced

staff members who knew the patients, in all

six staff members in each ward. This gives an

obvious weakness with possible bias in the

form of a positive pre/post evaluation. We were

aware of this bias factor, and tried to reduce this

confounding factor by:

Not informing staff about the purpose

the pre/post MADRS measurements.

These measurements were divulged as a

way to chart the level of depression in a

nursing home population, with control of

variations over time. This does not rule

out the possibility that the real motivation

of the measurements were guessed or

intuited by the interviewed staff members,

but we believe that this at least reduced

the likelihood of bias towards the music

therapy intervention.

We let two experienced staff members

who knew the residents make independent

ratings, initially blinded to the evaluation

of the other. We sought consistency

between the raters, although the figures

were too small to evaluate statistically.

Another factor that may have been able

to reduce bias was that attitudes towards

music therapy varied strongly among staff,

uncovered by depth interviews at an earlier

stage of the project. Several of the staff

members used as raters were convinced

that music therapy had effect on clinical

symptoms, whereas other staff members

used as raters looked at music therapy as a

pasttime to create diversion from boredom,

and had weak beliefs that it could work on

clinical symptoms.

We also tried to reduce bias by not

divulging results of the first test while

rating the second time.

38

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

Another obvious source of bias is the use of the

author as interviewer. We sought guidance on how

to reduce this source of bias. The interviewer tried

to use a neutral appearance and body language

during interviews, and consciously employed

low degrees of directiveness while interviewing,

as outlined in Whytes Directiveness Scale for

analysing interview technique (Britten, 1995).

The medical doctor directing treatment at the

institution was not in contact with the project. We

therefore have the opinion that changes in music

therapy activity did not lead to bias in form of

changes in regular medical treatment policies.

The Possible Interaction between Medical

Treatment and Music Therapy

We had several cases during the study that

indicated that a combination of pharmaceutical

treatment and music therapy tailored to the

clinical picture of the patient will give added

benefit. When the presentation of symptoms of

depression was mixed with anxiety and agitation,

the individualized music therapy measure would

use a calming and comforting. Patients who had

a catatonic, frozen, passive form of depression,

on the other hand, benefited from music therapy

measures that used positive energizing elements.

Patients who had difficulty coping with losses,

stuck in a grieving process, benefited from

familiar songs and music that could help work

through emotional difficulties. The choice of

pharmaceutical treatment would in several cases

be informed by this conscious use of musical

elements tailored to the patients needs. In some

cases, the music therapy sessions uncovered pain

that had not been treated adequately, for instance,

and could thus aid in shedding light on clinical

presentations that are often difficult to decipher

(Myskja, 2005). How different forms of treatment

given the same individual, e.g., drugs and music

therapy, influence each other mutually, is an

area that has so far been inadequately addressed

in the research literature, and would be another

important area for future exploration (Rajendran,

Thompson & Reich, 2001).

The Day the Music Died

Conclusion

A study with a pre-post design, involving all

the residents in a Norwegian nursing home that

were able to participate, compared a no music

condition with a music condition, instigated by

a temporary pause in music therapy services. The

measurements of depression levels by the use of

MADRS showed an overall significant reduction

in depression levels in the institution when the

music therapy services were resumed compared

to the end of an 11-week period when the music

therapy aide had a leave of absence. Measurement

of depression levels showed a similar reduction in

depression levels in all three wards in the music

condition, compared with the no music condition.

The reduction in depression showed a correlation

to the degree of participation in the music therapy

groups. High levels of participation were linked

to a large reduction in depression. Low levels of

participation in the music therapy groups were

linked to advanced disease, more than to previous

relationship to music.

The present study has methodological

limitations; however, it does address issues

inadequately dealt with in music therapy

literature. The robust effect found in the study

needs to be followed by larger controlled studies

to give stronger evidence not only of the efficacy

of music therapy, but also clearer indications of

which approaches to the use of music are the most

effective and give the best utilization of available

resources.

Acknowledgments

Oslo Church City Mission, for practical help;

Health and Rehabilitation, for project funding;

G C Rieber Foundations, for study funding;

Torgeir Bruun Wyller and Brynjulf Stige, for

helpful advice.

References

Beavis, D., Simpson, S, & Graham, I. (2002) A

literature review of dementia care mapping:

Methodological considerations and efficacy.

Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

Nursing, 9, 725-736.

Britten, N. (1995). Qualitative research:

Qualitative interviews in medical research.

British Medical Journal, 311, 251-253.

Brooker, D. (2004). What is person-centred care

in dementia? Reviews in Clinical Gerontology,

13, 215-222.

Brotons, M., Marti, P. (2003). Music therapy

with Alzheimers patients and their family

caregivers: A pilot project. Journal of Music

Therapy, 40, 138-150.

Brotons, M. (2000) An overview of the music

therapy literature relating to elderly people. In

D. Aldridge (Ed.), Music therapy in dementia

care (pp. 33-62). London: Jessica Kingsley

Publishers.

Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the

behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Publishers.

Dileo, C., Bradt, J., Murphy, K., Keith, D. &

Zanders, M. (2002). Medical music therapy:

Current knowledge and agendas for future

research. Paper presented at the 10th World

Congress of Music Therapy, Oxford, England.

Gold, C. (2004). The use of effect sizes in music

therapy research. Music Therapy Perspectives,

22, 91-95.

Hanser, S. B. & Thompson, L. W. (1994). Effects

of a music therapy strategy on depressed older

adults. Journal of Gerontology, 49, 265-269.

Hanser, S. B. (1990). A music therapy strategy

for depressed older adults in the community.

Journal of Applied Gerontology, 9, 283-298.

Hilliard, R. (2005). Music therapy in hospice

and palliative care: A review of the empirical

data. Evidence-based Complementary and

Alternative Medicine, 2, 173-178.

Hsu, W. C. & Lai, H. L. (2004). Effects of music

on major depression in psychiatric inpatients.

Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 18, 193199.

Maratos, A. & Gold, C. (2003). Music therapy

for depression. [Protocol] Cochrane Database

of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4. Art. No.:

CD004517.

DOI:

10.1002/14651858.

CD004517.

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

39

The Day the Music Died

Montello, L. & Coons, E. E. (1999). Effects of

active versus passive group music therapy

on preadolescents with emotional, learning,

and behavioral disorders. Journal of Music

Therapy, 35, 49-57.

Mottram, P., Wilson, K., & Strobl, J. (2006).

Antidepressants for depressed elderly.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,

Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003491. DOI

10.1002/14651858.CD003491.pub2.

Muller-Thomsen, T., Arlt, S., Mann, U., Mass,

R. & Ganzer, S. (2005). Detecting depression

in Alzheimers disease: Evaluation of

four different scales. Archives of Clinical

Neuropsychology, 20, 271-276

Myskja, A. (2006). To prosjekter i eldreomsorgen.

In T. Aasgaard (Ed.), Musikk og helse. Oslo:

Cappelen forlag.

Myskja, A. (2005). Metodebok systematisk bruk

av musikk i eldreomsorgen. Oslo: Unikum

forlag.

Ness, J. (2004). Demographics and payment

characteristics of nursing home residents in

the United States: A 23-year trend. Journals

of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences

and Medical Sciences, 59, 1213-1217.

Opie, J., Rosewarne, R., OConnor, D.W. (1999).

The efficacy of psychosocial approaches to

behaviour disorders in dementia: A systematic

literature review. Austral New Zeal J Psychiatr,

33, 789799.

Rajendran, P. R., Thompson, R. E. & Reich, S.

G. (2001). The use of alternative therapies by

patients with Parkinsons disease. Neurology,

57, 790-794.

Rao, V. & Lyketsos, C. G. (2000). The benefits

and risks of ECT for patients with primary

dementia who also suffer from depression.

International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,

15, 729-735.

Ridder, H. M. O. (2004). When dialogue fails.

Music therapy with elderly with neurological

degenerative diseases. Music Therapy Today,

V. Retrieved 09.12.2004 from http://www.

musictherapyworld.de.

Ridder, H. M. O. (2005). Individual music therapy

with persons with Frontotemporal Dementia.

40

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 17(1) 2008

Singing dialogue. Nordic Journal of Music

Therapy, 14 (2), 91-106.

Selbk, G., Kirkevold, . & Engedal, K. (2006).

The prevalence of psychiatric symptoms

and behavioural disturbances and the use of

psychotropic drugs in Norwegian nursing

homes. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry, 22, 843-849.

Small, J. & Gutman, G. (2001) Recommended and

reported use of communication strategies in

Alzheimer caregiving. Journal of Alzheimer`s

Disease and Associated Disorders, 4, 270278.

Standley, J. M. (2000). Music research in medical/

dental treatment: an update of a prior metaanalysis. In C. Furman (Ed.), Effectiveness of

music therapy procedures: Documentation of

research and clinical practice. Silver Spring,

MD: National Association for Music Therapy.

Teresi, J. (2001). Prevalence of depression and

depression recognition in nursing homes.

Journal of the Society of Psychiatry and

Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36, 513-520.

Thaut, M. H. (2005). The future of music in

therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of

Sciences, 1060, 303-308.

VanItallie, T. B. (2005). Subsyndromal

depression in the elderly: Underdiagnosed and

undertreated. Metabolism, 54, 39-44.

Weyerer, S, Mann, A. H., & Ames, D. (1995).

Prevalence of depression and dementia in

residents of old age homes in Mannheim and

Camden (London). Zeitung fr Gerontologie

und Geriatrie, 8, 169-178.

World Health Organisation (2007). Depression

[online]. Retrieved July 2, 2007, from http://

www.who.int/mental_health/management/

depression/definition/en/.

World Health Organisation (2006). Mental

health and brain disorders [online]. Retrieved

December 31, 2006, from http://www.who.int/

topics/depression/en/.

Wigram, T. (2002). A comprehensive guide to

music therapy - theory, clinical practice,

research and training. London: Jessica

Kingsley Publishers.

Você também pode gostar

- Metabolic Changes in Diabetes MellitusDocumento39 páginasMetabolic Changes in Diabetes MellitusAlyssa Leones0% (2)

- BaltimoreDocumento1 páginaBaltimoreAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Medical MnemonicsDocumento256 páginasMedical MnemonicssitalcoolkAinda não há avaliações

- Incentive SpirometryDocumento2 páginasIncentive SpirometryAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Characteristics of Youth PJPII TTDocumento4 páginasCharacteristics of Youth PJPII TTAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Local Government Code TaxesDocumento56 páginasLocal Government Code TaxesAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics Application (Philosophy)Documento4 páginasEthics Application (Philosophy)Alyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Predictors of DepressionDocumento6 páginasPredictors of DepressionAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Identification of The Needs of Haemodialysis Patients Using The Concept of Maslow's Hierarchy of NeedsDocumento8 páginasIdentification of The Needs of Haemodialysis Patients Using The Concept of Maslow's Hierarchy of NeedsAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Velveteen RabbitDocumento5 páginasVelveteen RabbitAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- The Principle of Double EffectDocumento1 páginaThe Principle of Double EffectAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy and Physiology of SystemsDocumento14 páginasAnatomy and Physiology of SystemsAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- The Principle of Double EffectDocumento1 páginaThe Principle of Double EffectAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- NCP FeverDocumento2 páginasNCP FeverAlyssa LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Formative Gen EdDocumento119 páginasFormative Gen EdDan GertezAinda não há avaliações

- PCT For BodybuildersDocumento12 páginasPCT For BodybuildersJon Mester100% (4)

- Rodríguez DinamometríaDocumento5 páginasRodríguez DinamometríaMariana Covarrubias SalazarAinda não há avaliações

- Detect Pharmaceutical Health Hazards and ActDocumento81 páginasDetect Pharmaceutical Health Hazards and Acttemesgen dinsaAinda não há avaliações

- Surgery MCQDocumento24 páginasSurgery MCQMoiz Khan88% (8)

- Medsurg 3 Exam 1Documento55 páginasMedsurg 3 Exam 1Melissa Blanco100% (1)

- Eye LubricantDocumento9 páginasEye LubricantbuddhahandAinda não há avaliações

- A Drug Study On PrednisoneDocumento5 páginasA Drug Study On PrednisonePrincess Alane MorenoAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar On: Organisation and Management of Neonatal Services and NicuDocumento27 páginasSeminar On: Organisation and Management of Neonatal Services and NicuDimple SweetbabyAinda não há avaliações

- DEVPSY Reviewer - Chapters 1-6 PDFDocumento19 páginasDEVPSY Reviewer - Chapters 1-6 PDFKathleen Anica SahagunAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges of Catholic Doctors in The Changing World - 15th AFCMA Congress 2012Documento218 páginasChallenges of Catholic Doctors in The Changing World - 15th AFCMA Congress 2012Komsos - AG et al.Ainda não há avaliações

- Adams4e Tif Ch47Documento19 páginasAdams4e Tif Ch47fbernis1480_11022046100% (1)

- Do No Harm by Henry Marsh ExtractDocumento15 páginasDo No Harm by Henry Marsh ExtractAyu Hutami SyarifAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnostic Ultrasound Report TemplatesDocumento8 páginasDiagnostic Ultrasound Report TemplatesJay Patel100% (10)

- Knowledge Regarding Immunization Among Mothers of Under Five ChildrenDocumento3 páginasKnowledge Regarding Immunization Among Mothers of Under Five ChildrenEditor IJTSRDAinda não há avaliações

- CCRT Cervix2Documento27 páginasCCRT Cervix2Marfu'ah Nik EezamuddeenAinda não há avaliações

- Bioaktivni Ugljenihidrati PDFDocumento4 páginasBioaktivni Ugljenihidrati PDFmajabulatAinda não há avaliações

- Postherpetic Neuralgia NerissaDocumento18 páginasPostherpetic Neuralgia Nerissanerissa rahadianthiAinda não há avaliações

- Wild and Ancient Fruit - Is It Really Small, Bitter, and Low in Sugar - Raw Food SOSDocumento73 páginasWild and Ancient Fruit - Is It Really Small, Bitter, and Low in Sugar - Raw Food SOSVictor ResendizAinda não há avaliações

- Application For Life and Health Insurance ToDocumento5 páginasApplication For Life and Health Insurance Toimi_swimAinda não há avaliações

- Semey State Medical University: Department of Psychiatry Topic Schizophrenia Raja Ali HassanDocumento45 páginasSemey State Medical University: Department of Psychiatry Topic Schizophrenia Raja Ali HassanRaja HassanAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Title and SynopsisDocumento11 páginas1 Title and SynopsisMuhammad Arief ArdiansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Community Theatre and AIDS Studies in International Performance PDFDocumento194 páginasCommunity Theatre and AIDS Studies in International Performance PDFgabriella feliciaAinda não há avaliações

- Hospital IndustryDocumento30 páginasHospital IndustryArun.RajAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiac Cycle: DR Rakesh JainDocumento97 páginasCardiac Cycle: DR Rakesh JainKemoy FrancisAinda não há avaliações

- Khalil, 2014Documento6 páginasKhalil, 2014Ibro DanAinda não há avaliações

- Reconocimiento Del Acv CLINISC 2012Documento21 páginasReconocimiento Del Acv CLINISC 2012Camilo GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 8-Q1-TG PDFDocumento34 páginasGrade 8-Q1-TG PDFMerlinda LibaoAinda não há avaliações

- PN NCLEX - Integrated (A)Documento63 páginasPN NCLEX - Integrated (A)fairwoods89% (19)

- Perkutan Kateter Vena Sentral Dibandingkan Perifer Kanula Untuk Pengiriman Nutrisi Parenteral Ada NeonatusDocumento3 páginasPerkutan Kateter Vena Sentral Dibandingkan Perifer Kanula Untuk Pengiriman Nutrisi Parenteral Ada NeonatusmuslihudinAinda não há avaliações