Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

OF Resp: On Sides of Mountains, Planes Carry

Enviado por

TheNationMagazineTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OF Resp: On Sides of Mountains, Planes Carry

Enviado por

TheNationMagazineDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Communists.

Most of therefugees are eitherthe

very old or thevery young.

Then too, the governments control overmany

refugeesmay be only temporaly. The worship of

phi-animistic spirits-is

a national religion that

exertsa

tremendous influence over Laotians. It

holds that when a man leaves his native village, the

ancestral spirits arepowerless to protect him. It may

be only a matter of time before this belief draws

manyrefugeesback

to their bombed-out villages,

many of which lie in Communist-held territory.

7

8

46

Faced with the refugee problem, in great part

its own making, the United Stateshasset

about to

treat the symptoms more than the cause. Since 1963

it has spent nearly $3 million to feed and resettle

refugees. This year alone the cost could reach $10

million. The largest part of the program is food distribution. More than 7,000 tons of rice are handed

WAR CRIMES

CLE OF RESP

THE

L~

RICHARD A. FALK

Mr. F d k , a member of the poktical science faculty at Princeton Unaversity, is spending the current academic year at the

Center for Advanced Study i n the Be!zavioral Sciences at

Stanford University. He 2s the author of Legal Order in a

Violent World [Princeton Univematy Press).

If certain acts in violation of treatles are crimes, they

are crimes whether the United States does them or

whetherGermany does them, and we are not prepared

to lay down a rule of criminal, conduct against others

which we would not be wiIlmg to have invoked against us.

-Mr. Justice Robed Jackson,

The dramatlc cbsclosure of the Song My massacre

has aroused public concern over the commission of

war crimes in Vietnam by American military personnel. Such a concern, while certainly appropriate,

IS insufficient if limited to inquiry and prosecution

of the individual servicemen who particlpated in the

monstrous events that may have taken the Lives of

more than 500 civilians In the My Lai No. 4 hamlet

of Song My village on March 16, 1968.

Song My stands out as a landmark atrocity in the

history of warfare,andits

occurrence is a moral

challenge to the entire American society. This challenge was stated succinctly by Mrs. Anthony Meadlo, themother of David Paul Meadlo, one ofthe.

killers at Song My: I sent them a good boy, and they

madehim a murderer. (The New York Times,

November 30, 1969.) Another characteristicstatement about the general nature of the war was attributed toall army staff sergeant: We areat war

THE

NATIONIJUWX~

26, .Z%O

with the ten-year-old children. It may not be humanitarian, but thats what its like.? (-The New York

Times, December 1, 1969.) The massacre itself raise::

a seriousbasis for inquiry into thernihtaryand

civilian command structurethat was 111 charge of

battlefield behavior at the time.

However, evidence now available suggests that the

armed forces have tried throughout the Vietnamese

War to suppress, rather than to investlgate and punish, the comrnissron of war crimes by American personnel. The evrdence also suggests a failure to protest or prevent the rnanlfest and systematic con7mission of war crimes by the armed forces of the Saigon

regime.

Thus a proper inquirymustbe

conducted on a

scope much broader than any single day of slaughter. The offzczal policzes developed for the pursuit of

belligerent objectives in Vietnam appear to violate

the same basic and minimum constraints on the conduct of war as were violated at Song My. The B-52

pattern raids against undefended villages and populatedareas,free

bomb zones, forcibleremoval

of civillan population, defoliatmn and crop destruction, and search and destroy missions have been

sanctioned by the United States Government. Each

of these tactical policies appears to violate international laws of war that are binding upon the United

States by international treaties ratified by the government, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

The overall American conduct of the war involves a

refusal to differentiate between combatants and nom

combatants and between milltaryandnonmilitary

targets. Detailed presentatlon of such acts of war in

I

Chief Prosecutor for the Unated States

ut the Nuremberg Tribunals

out each month, much of it dropped from the air in

what is considered historys greatest rice drop. Flying over rugged mountains at altitudes as low, as 500

feetand

rislring Communist fire, civilian planes

drop 500-pound sacks to isolated refugees below.

The Unlted States also operates a continual air

lift to relocate the population. From short dirt airstrips leveled on sides of mountains, planes carry

thousands of refugees dally out of war zones to government-controlled cities such as Paxse, Sayaboury

and Vientiane.

Arriving in such places, therefugees are driven

to camps that resemble the shantytowns of the Great

Depression. There, a few women cook rice provided

by AID. Children play tag or rummage for odd bits

,of sticks and stones on the ground. Most of the people

eithersit dozing, waiting listlessly-sometimes for

months,sometimes

for years-for jobs and new

homes.

0

77

relation -to the laws of waris contained in In the

Name of America, published under the auspices of

the Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam,

in January 1968-several months before the Song My

massacre took place. Ample evidence of war crimes

has been presented to the public and to its leaders

for some time, but it has not produced official reaction or rectifying action. A comparable description

of the acts of war that were involved in the bombardment of North Vietnam by American planes and

navalvessels between February 1965 and October

1968 may be found in North Vietnum: A Documentary, by John Gerassi.

The broad point is that the United States Government has officially endorsed a series of battlefield

activities that appear to qualify as warcrimes. It

would, therefore, be misleading to isolate the awful

happenings a t Song My from the overall conduct of

the war. Certainly, the perpetrators of the massacre

are, if the allegations prove correct, guilty of war

crimes, but any trial pretending to p s k e must consider the extent to which they were executmg supen o r orders or were carrying out the general line of

official policy that established a moral clzmate.

The U.S. prosecutor at Nuremberg,Robert

Jackson, emphaslzed that war crimes are war crimes

no matter what country commits them. The United

States more than any other sovereign state took the

lead in the movement to generalize theprinciples

underlying the Nuremberg judgment. At .its initiative, the General Assembly of the United Nations

1945 unanimously affirmed the principles of international law recognized by the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal in Resolution 95(I). This resolution

was an official action of governments. At the direction of the UN membership, the International Law

Commission, a body of internatlonal law experts

fromalltheprincipallegalsystems

in the world,

formulatedthePrinciples

of Nurembergin

1950.

These sevenPrinciples

of Internatlonal Law are

printed in full in the adjoining box, to indicate the

basic standards of international responsibility governing the commission of warcrimes.

Neither the Nurernberg judgment nor the Nuremberg principles fixesdefinlte

boundaries on personal responsibility, These will have to be drawn as

thecircumstances of alleged violations of international law are tested by competent domestic and

international

tribunals.

However, Principle IV

makes it clear that superior orders, are no defense

in a prosecution for warcrimes, provided the individual accused of criminal behavior had a moral

choice available to him,

The United States Supreme Court upheld in The

Matter of Yamashita 327 US. I (1940) a sentence of

death pronounced on GeneralYamashita for acts

committed by troops under his command in World

War 11. The determination of responsibility rested

upon the obligation of General Yamashita to main,

Principles of Internatlonal Law Recognized in

the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and

in the Judgment of the Tribunal

As formulated by the International Law Cornmission,

June-July, 1950.

Prhclple T

Any person who commits an act which constitutes a

crime under international law is responsible therefor

and liabIe to punishment.

Principle I1

The fact that internal law does not impose a penalty

for an act which constitutes a crime under international

law does not relieve the person who committed the act

from responsibility under international law.

Principle I11

The fact that a person who committed an act which

constrtutes a crime under international law acted as

Head of State or responslble government officialdoes

not relieve him from responsibility under international

law.,

Principle IV

The factthat a person acted pursuant to order of

his Government or of a superior doesnot relieve him

from responsibility under international law,provided

a moral choice was in fact possible for him.

Principle V

Any person charged with a crime under international

law has the right to a fair trial on the facts and law.

- Principle VI

The crimes hereinafter set out are punishable as

crimes under international law:

a. Crimes against peace:

(i)Planning, preparation, initiation or waging of

a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties,agreementsor

assurances:

(ii) Participation in a common plan or conspiracy

for the accomplishment of any of the acts mentioned under (i).

b. War crimes:

Violatrons of the laws or customs of war which

include, but are not limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave-labour or far any

other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on theseas, killing of

hostages, plunder of public or private property,

wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or

devastation not justified by military necessity.

c. Crimes against humanity:

Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation

and other inhuman acts done against any civilian

population, or persecutions on political, racial or

religious grounds,when such acts are done or

such persecutions are carried on in execution of

or in connexion with any crime against peace or

any, war crime.

Principle VI1

Complicity in the commission of a crime against

peace, a warcrime, or a crime against humanity as

set forth in Principle VI is a crime under international

law.

78

tain discipline among troops under his command,

whlch discipline included enforcement of the prohibition agalnst the commission of war crimes. Thus

General Yalnashita was convicted, even thoughhe

had no specific knowledge of the alleged war crimes.

Commentators have criticized the conviction of General Yamashita because it was dlfflcult t o mamtain

discipline underthe conditions of defeat that prevailed when thesewarcrlmeswerecommittedin

the Philippines, but the imposition of responsibility

for holding principal

in this casesetsaprecedent

military and political officials responsible for acts

committedundertheircommand,

especially when

no ,diligent effort was made to inquire into and punish crimes, or prevent their repetition. The Matter

of Yamashita has vivid relevance to the-failure of

the U.S. military command to enforce observance

of the minimumrules of international law anlong

troops serving under their commandin Vietnam. The

following sentencesfrom themajority

opinion of

Chief Justice Stone in The Mutter of Yamashita has

a particular bearing :

It is evident that the conduct of military operations by

troops whose excesses are unrestrained by the orders or

efforts of their commands would almost certainly result

in violations which it is the purpose of the law of war to

prevent. Its purpose to protect civilian populations and

prisoners of war from brutality would largely be defeated

if the commands of an invading army could with impunity

neglect to take responsible measures for their protection.

Hence the law of war presupposes that its violation is to

be avoided through the control of the operation of war by

commanders who are to some extent responslble for their

subordinates. [327 U.S.1, 151

In fact,the effectiveness of the law of war depends, above all else, on holding those in command

and in policy-making positions responsible for rankand-file behavior on the field of battle. The reports

of neuropsychiatrlsts,trained

in combattherapy,

have suggested that unrestramed troop behavior 1s

almost always tacitly authorized by commanding officers-at least to theextent of conveying theimpression that outrageous acts will notbe punished.

It would thus be a deception to punish the trigger

men at Song My without also looking higher on the

chain of command for the real source of responsibility.

The Field Manual of the Department of the Army,

F M 27-10, adequately develops the principles of responsibility governing members of the armed forces.

It makes clear that the law of war is binding not

onlyupon States as such but also upon individuals

and, in particular, the members of theirqrmed

forces The entire manual is based upon the acceplance by the United States

of the obligalion toconduct warfare in accordance with theinternational

law of war. The substantive content of international

law is contained in a series of international treaties

that have been ratified by the United States, including principally the fiveHague Conventions of 1907

andthefour

Geneva Conventions of 1949.

These internationaltreaties are part of the su-

prelne law of the land by virtue

of Article VI of

the U.S. Constitution. Customary rules of international law gov&rnlngwarfare are also applicabk to

the obligations of American citizens.

It hassomeiimes been maintained that the

laws of war do not apply to a civil war, which is a

war within a state, and some observers have argued

that the war in Vietnam represents a civil war between factions contending for political control, of

South Vietnam. That view may accurately portray

theprincipalbasis

of conflict (though the official

American contentlon, repeated by President Nixon

on November 3, is that South Vietnam, a sovereign

state,has

been attacked by anaggressorstate,

North Vietnam), but surely the extension of the combat theatre to include North Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Cambodla and Okinawa removes any doubt

about the international character of the war from a

military and legal point of view. But even if one assumes that the war should be treated as a civil war,

the laws of war are appllcable to an extent great

enough to cover the events at Song My and the commission of many other alleged war crimes in Vietnam. The Field Manual incorporates Article 3 of

the Geneva Conventions of 1949, which establishes a

minimum set of obligations for clwl war situations:

In thecase of armed conflict not of an international

characteroccurrlng in theterritory of one of the High

Contracting Parties, each Party to the conflict shall be

bound to apply, as a minimum, the following provisions:

(1) Persons takmg no active part in the hostilities, m eluding members of armedforces who havelaid

down their arms and those pIaced hors de combat

by sickness: wounds, detention, or any other cause,

shall in all circumstances be treated humanely,without any adverse distinction founded dn race, colour,

religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other

similar criteria

To thisend, the following acts are andshall remain prohibited at any tlme and in any place what-,

soever wlth respect to the above-mentioned persons:

violence to-life and person, ~n particula; murder

of allkinds,mutilaiion,cruel

treatmentand

torture;

taking of hostages;

outrages upon personal dignity, inparticular,

humiliatmg and degrading treatment;

thepassing of sentencesand the carrying out

of executions without previous judgmentpronounced by a regularlyconstitutedcourt,

affording all the jud~cialguarantees which are

recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

(2) The wounded and sick-shall be collected and cared

for. An impartial humanitarian body, such as the

International Coinmittee of the Red Cross, may offeritsservices to the Parties to the conflict.

The Parties to the conflict should further endeavor

to bring into force, by means of special agreements,

all orpart of the other provisions of thepresent

Convention.

I havealready suggested

that many officlal battlefield

the Uniied States in Vieham

These official policies should

that thereis evldence

policies relied upon,by

amount t o war crimes.

be investigated in light

79

THE N A T I O N / ~ a26=

~ 1970

~ ~ ~

odthe legal obligations of the United States. If found

to be illegal; such policies should be discontinued

forthwith and those responsible for the policy and its

execution should be prosecuted as war criminals by

appropriate tribunals. These remarks definitely apply to the following war policies, and very likely to

others: (1) the Phoenix Program; (2) aerialand

naval bombardment of undefended vilIages; (3) destruction of crops andforests; (4) search-and-destroy missions; (5) harassment and interdiction

fire; ( 6 ) forclble removal of civilian population; (7)

reliance on avariety

of weapons prohibited by

treaty.

In addition, all allegations of particular war atrocities should beinvestigatedandreported

upon by

impartial and responsible agencies of inquiry. These

acts-committed in defiance of declared official

policy-should be punished. Responsibility should be

imposed upon those who inflicted the harm, upon

those who gave direct orders, and-upon those whose

powers of command included insistence upon overall

battlefield discipline and the prompt detection and

punishment of war crimescommitted within the

scope of their authority.

Political leaders who authorized illegal battlefield

practicesand policies, or who had knowledge of

thesepractices and policies and failed to act are

similarly responsible for the commission of war

crimes. The following paragraph from the majority

judgment of the Tokyo War CrimesTribunal

is

relevant:

A member of a Cabinetwhichcollectively, as one of

the principal organs of the Government, is responsible

for the care. of prisoners is not absolved from responsibility if, having knowledge of the commission of the crimes

in thesensealready discussed, and omitting or failing

to secure the taking of measures to prevent the commission of such crimes in the future, he elects tocontinue

as a member of the Cabinet.This is the position even

though the Department of which he has the charge is not

dlrectly concerned with the care of prisoners. A Cabinet

ao

member may resign. If he has knowledge of ill-treatment

of prisoners, is powerless to prevent future ilI-treatment,

buteIects

to remaininthe

Cabinet thereby continuing

to participate in its collective responsibiIity for protection

of prisoners he willingly assumes responsibility for any

ill-treatment in the future.

Army or Navy commanders can, by order, secure propertreatment and prevent ill-treatment of prisoners. So

chn M~nrstersof War and of the Navy. If crimes are

committed against prisoners under their control, of the

likely occurrence of which they had, or should have had

knowledge in advance, they are responsible for those

crimes. If, for exampIe, itbeshown that within the units

under his command conventional war crimes have been

committed of which he kneworshould

have known, a

commander who takes no adequate steps to prevent the

occurrence of such crimes in the future will be responsible for such future crimes.

The United States Government was directly associated with the development of a broad conception

of criminal responsibility for the leadership of a

state during war. A leadermusttakeaffirmative

acts to prevent war crimes or

dissociate himself from

the government. If he fails to do one or the other,

then by the very actof remaining in a government of

a state guilty of warcrimes,he

becomes a war

criminal.

Tokyo

Finally, as both theNurembergandthe

judgments emphasize, a government official is a war

criminal if he has participated in the initiation or

execution of an illegal war of aggression. There are

considerable grounds for regarding the United States

involvement in the Vietnamese War-wholly apart

from the conduct of the war-as involving violations

of the UN Charterand other treaty obligations of

the United States. (See analysis of the legality of

U.S. participation in Vietnam and International Law,

sponsored b y the Lawyers Committee on American

Policy Towards Vietnam; see also R. A. Falk, editor,

The Vietnam War and International Law, Vols. 1

and 2.) If U.S. participation in the war is found illegal, then the policy makers responsible for the war

THZ N A T I O N / ~ U T l w l l . 26,

~ 1970

b.

during its various stages would be SUbJeCt to prosecution as alleged warcriminals.

The idea of prosecuting war criminals involves

using international law as a sword against violators

in themilitary and civilian hierarchy of government. But the Nuremberg principles imply a broader

1,Jman responsibility tooppose an iblegal war and

illegal methods of warfare. There is nothing to suggest that the ordinary citizen, whether within or outside the armed forces, IS potentially gullty of a war

crime merely as a consequence of such a status. But

there are grounds to maintain that anyone who believes or has reason to believe that a war is being

waged in vlplation of minimal canons of law and

moralityhasan

obligation of conscience to resist

participation .in and support of that war effort by

everymeans at his disposal. Inthat respect,the

Nuremberg principles provide guidelines for citizens3

conscience and a shieZd that can be used in the

domestic legalsystem to interpose obligations under

international lawbetween the government and members of the society. Such a doctrine of Interposition

has been asserted in a large number of selective

servicecases by indwiduals refusing to enter the

armed forces. It has already enjoyed a limted success in the case of U.S. v. Szsson, the appeal from

which decision is now before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The issue of personal conscience 1s ralsed for

everyone 111 the United States. It 1s raised more directly for anyone called upon to serve in the armed

forces. It is raised m a special way for parents of

minor children who are conscripted into the armed

forces. It is raised for all taxpayers who support the

cost of the war. A major legal test of the responsiveness of our judicial system to the obligations of

the country to respectinternatlonal law is being

mounted in a taxpayersysuitthathas

been organized by Pierre Noyes, a professor of physics at

Stanford University. In this class action the effort is

to induce the court to pronounce upon whether it is

permissible to use tax revenues to payfor a war

that violates the U.S. Constitution and duly ratified

international treaties. The issue of responsibility is

raised for all citizens who in varmus ways endorse

thewar policies of the government. The circle of

responsibility is drawn around all who have or

should have knowledge of the illegal and immoral

character of the war. The Song My massacre puts

every American on notice as to the character of the

war. The imperatives of personal responsibility call

upon each of us to search for effective means to

bring the war to an immediate end.

And thecircle of responsibility does not end at

the border. Foreign governments and their populations are pledged by the Charter of the united Nations to oppose aggression and to take steps to punish war crimes. The cause of peace is indivisible,

andall those governments and people concerned

with Charter obligations havealegalandmoral

duty to oppose the American involvement in VietTHE NATIQN/JUlzzlar~ 2E3 1970

nam and to support the effort tb identify, prohibit

and punish war crimes. The conscience of the entire

world community is implicated by inaction, as well

as by more explicit forms of support for U.S. policy.

Some may say that war crimeshave been committed by both sides in Vietnam and that, therefore,

if justice is to be even-handed, North Vietnam and

the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South

Vietnam should be called upon to prosecute their officials guilty of war crimes. Such a contention needs

to be evaluated. however, in the overall context of

the war, especially in relation to the identification

of which side is the victim of aggression and which

side is theaggressor. But whatever grounds there

may be $or afttempting to strike a moral balance of

this sort, the allegation that the other side is also

guilty does not operate as a legal defense against a

warcrimes indictment. That question was clearly

litigated anddecided at Nuremberg.

Others have argued thattherecan

be no war

crimes in Vietnain because war has never been declared by the U.S. Government. The failure to declare war under these circumstances raises a substantial constitutional question, but it has no bearing

upon the rights and duties of the United States under

international law. A declaration of war is a matter

of internal law, but the existence of combat circuinstances is a condition of war that brings into play

the full range of obligations under international law.

1

Ratherthan encouraging a sense of futility,

the SongMy dmlosures give Americans a genuine

focus for concern and action. It now becomes possible to understand the human

content of counterinsurgency warfare as waged with modern weapons

and doctrines. The events at Sang My suggest the

need for a broad inquiry into the relationship between the civilian andmilitaryleadership

of the

country and into the systematic battlefield practices

of our forces in Vietnam. The occasion calls not for

self-appraisal by generals and government officials

but at a minimum a commission of citizens drawn

from all walks of life and known for theissense of

scruples. We need aPresidential commission that

has access to all records and witnesses, and is empowered t o make public a report and recommendations for action. We also need a series of legal tests

in domestic courts, initiated onbehalf of such injured groups as civilian survivors of warcrimes,

young Americans who are in jail or exile because

they have contended all along that the American effort in Vietnam violates international law, and servicemen who refuse to obey orders to fight in Vietnam, who complain of the illegality of superior

orders, or who seek to speak out and demonstrate

against continuation of the war.

On a world scale, it would seem desirable for the

UN to mount an investigation of alIegations of war

crimes, especially inrelation to Vietnam and Nigeria. It would also seemappropriate for the UN

to organize a world conference to reconsider the

;laws oi wars as related to Contemporary forms of

warfare. The world peace conferences of 1899 and

1907 at TheHaguemightserve

as precedents for

, such a conference call. Such an expression of world

conscience isdesperately needed at this time. We

also need a new set of internationaltreatiesthat

will bind governmentsintheirmilitaryconduct.

Given the perils and horrors of the contemporary

world, it is time that mdividuals everywhere called

their governments to account for indulgmg or ignaring the dally evidences of barbarism. We are destroying ourselves by destroying the environment

that perrnlts life to flourish, and we are destroying

our polity by destroying the values of decency that

might allow men eventually to live together in dignlty. The obsolete pretensions of sovereign prerogative and military necessity had better be challenged

so011 if life on earth 1s to survive,

POLITICS OF THE

6NMENT

GENE MARINE

MT.Marine,editor and journalist specializing in Phe West

Coast scene, is the author of America the Raped (Simon &

Schuster).

A graduate studentin

zoology, fifteen yearsmy

junior, looked at me across the long trestletable

and grinned: You know, if it werent for the people

from Berkeley and thepeople from Georgia,this could

have been a pretty dull conference.

He

was

exaggerating-he was from Georgia and I am from

Berkeley-but he had something. There are conferencesand conferences, andthis one was different.

Because he reallymeant Berkeley, in the stereotyped

revolutionary sense, and he meant Georgla, maybe

not back-country cracker Georgia but notby any

means civil rlghts Georgia either.

The conferencewasthe

first of three organized

by the Institute for the Study of Health and Society,

.itself a Georgia organization, based in Decatur. They

callthem

,Conferences for the Developing Professional,and

runthem

with funds granted by

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

The idea is to come up with recommendations to

help HEW meet theproblems of the day.

Participants from around the country gathered at

a pleasant and isolated conference center

in the

Virginia countryside to hear the speakers youd expect at a meeting on TheEnvironment.There

were a front man from the oil industry and an official

of the Oil Workers Union, a couple of ecologists,

Charles Wurster of the Environmental Defense Fund

to talk about DDT, and Sen. Gaylord Nelson t o give

class. Eddie Albert, the actor, was an added starter

(and to everyones surprise, one of the most impressive speakers).

The participants were mostly between 25 and-35,

some younger, and they were medical students, law

students, architecture students, a few biologists, and

zoologists, some nurses, some mathematicians and

at least one dentist. They came because a faculty

member somewhere had taken an interest and urged

his graduate students to apply-or because somebody

stuck a notice up on a bulletin board and they

casually responded. They came from small campuses

and big ones, from internshipsin Pittsburgh and

New Orleansand fromthe Sociology Department

in Gamesville, Fla. They came with long hair and

sloppy clothes, and with short hair and singlebreasted three-piece suitsand quiet neckties. They

were people who would never have spoken a word

toone anotherin a million academic years.Past

40 (thoughstill, I hope, a developing professional),

I was invited because I had written a popular book

on ecology-popular as a description of style, not

a report on sales-and as a relief, I suppose, from

academIc solemnity.

We started on a Thursday (the oil people, systems

zoologist Kenneth Watt, and some arguments about

procedure), and that night,in a session unscheduled

by the organizers, we saw movies. SteveLevit,a

fourth-yearmedlcalstudent(psychopharmacology)

from San Franclsco and an active member

of the

Medlcal Committee on HumanRlghts, showed hls

own film on lastyears events atSanFrancisco

State and a frrlends film on what Berkeley calls

the Peoples Park War. These films, distributed by

the underground

group

called

Newsreel, are

unabashedlyrevolutionary

and theytriggered

a

discussion that lasted until three in the morning.

Some examples: A girl stood up intrembling

embarrassment to say that she follows the greatest

revolutionary of them all, Jesus Christ; a quiet 19-

,82

TYE NATION/JanwtrlJ

26. 1970

Você também pode gostar

- Law without Nations?: Why Constitutional Government Requires Sovereign StatesNo EverandLaw without Nations?: Why Constitutional Government Requires Sovereign StatesAinda não há avaliações

- L3 War, Aggression and State CrimeDocumento7 páginasL3 War, Aggression and State CrimeHabitus EthosAinda não há avaliações

- Jamia Millia Islamia: War CrimesDocumento6 páginasJamia Millia Islamia: War Crimesvishwajeet singhAinda não há avaliações

- West Morris Central High School Department of History and Social Sciences War CrimesDocumento3 páginasWest Morris Central High School Department of History and Social Sciences War CrimesYa Boi MikeyAinda não há avaliações

- No More War: How the West Violates International Law by Using 'Humanitarian' Intervention to Advance Economic and Strategic InterestsNo EverandNo More War: How the West Violates International Law by Using 'Humanitarian' Intervention to Advance Economic and Strategic InterestsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- ScriptDocumento6 páginasScriptMuzakkir AlamAinda não há avaliações

- What Happens During War Crime Trials? History Book 6th Grade | Children's History BooksNo EverandWhat Happens During War Crime Trials? History Book 6th Grade | Children's History BooksAinda não há avaliações

- International Humanitarian LawDocumento12 páginasInternational Humanitarian LawTirtha MukherjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Atrocity Fabrication and Its Consequences: How Fake News Shapes World OrderNo EverandAtrocity Fabrication and Its Consequences: How Fake News Shapes World OrderAinda não há avaliações

- Historical Development of ICCDocumento18 páginasHistorical Development of ICCKamaksshee KhajuriaAinda não há avaliações

- Inside The DMZ - The Most Fortified Border in the World: We Were Soldiers Too, #6No EverandInside The DMZ - The Most Fortified Border in the World: We Were Soldiers Too, #6Ainda não há avaliações

- Rights and Responsibilities: The Dilemma of Humanitarian InterventionDocumento10 páginasRights and Responsibilities: The Dilemma of Humanitarian InterventionChris Abbott100% (2)

- Decision-Making in Times of Injustice Lesson 16Documento18 páginasDecision-Making in Times of Injustice Lesson 16Facing History and Ourselves100% (2)

- A Rhetorical Crime: Genocide in the Geopolitical Discourse of the Cold WarNo EverandA Rhetorical Crime: Genocide in the Geopolitical Discourse of the Cold WarAinda não há avaliações

- Genocied Blac, BrownDocumento48 páginasGenocied Blac, Brownlio MwaniaAinda não há avaliações

- War Crime - WikipediaDocumento81 páginasWar Crime - WikipediaAnil KumarAinda não há avaliações

- One World Democracy03Documento13 páginasOne World Democracy0375599874097Ainda não há avaliações

- 9697 31 Nov 10Documento6 páginas9697 31 Nov 10cruise164Ainda não há avaliações

- The Punitive Turn in American Life: How the United States Learned to Fight Crime Like a WarNo EverandThe Punitive Turn in American Life: How the United States Learned to Fight Crime Like a WarAinda não há avaliações

- Crimes Against Humanity - Moot Court MemDocumento19 páginasCrimes Against Humanity - Moot Court MemRishab Singh100% (1)

- Solving The Puzzle of "Enemy Combatant" StatusDocumento94 páginasSolving The Puzzle of "Enemy Combatant" Statusoathkeepersok0% (2)

- History Notes - 2Documento8 páginasHistory Notes - 2Zahra LakdawalaAinda não há avaliações

- An Issue of Intent - The Struggles of Proving GenocideDocumento29 páginasAn Issue of Intent - The Struggles of Proving Genocidea190149Ainda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Ihl: Unit 1Documento53 páginasIntroduction To Ihl: Unit 1Vedant Goswami100% (1)

- War Crimes in The Middle EastDocumento7 páginasWar Crimes in The Middle Eastlegharihuda1Ainda não há avaliações

- War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityDocumento12 páginasWar Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityAyesha RaoAinda não há avaliações

- 13 Predictions - GriffinDocumento13 páginas13 Predictions - GriffinDrHemiAinda não há avaliações

- Humanitarian InterventionDocumento64 páginasHumanitarian Interventionsimti10Ainda não há avaliações

- When A War Is Not A WarDocumento5 páginasWhen A War Is Not A WarRojakman Soto TulangAinda não há avaliações

- Thirteen Predictions For The War On TerrorismDocumento13 páginasThirteen Predictions For The War On TerrorismMichael WilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Violations of Human Rights in Time of War As War CrimesDocumento14 páginasViolations of Human Rights in Time of War As War CrimesAtanu HaldarAinda não há avaliações

- Amendment I. Congress Shall Make No Law Respecting An Establishment ofDocumento10 páginasAmendment I. Congress Shall Make No Law Respecting An Establishment ofChristian MooAinda não há avaliações

- In The End, We Will Remember Not The Words of Our Enemies, But The Silence of Our Friends.Documento24 páginasIn The End, We Will Remember Not The Words of Our Enemies, But The Silence of Our Friends.AshleyStearnsAinda não há avaliações

- Pol Pot and Kissinger On War Criminality and Impunity by Edward S. HermanDocumento5 páginasPol Pot and Kissinger On War Criminality and Impunity by Edward S. HermanKeith KnightAinda não há avaliações

- Instructions For The Government of Armies of The United States in The FieldDocumento7 páginasInstructions For The Government of Armies of The United States in The FieldSonuAinda não há avaliações

- International Crimes Law and Practice Volume I Genocide Guenael Mettraux Full ChapterDocumento77 páginasInternational Crimes Law and Practice Volume I Genocide Guenael Mettraux Full Chapterevelyn.noyes345100% (3)

- Communist War in POW Camps 28 January 1953Documento55 páginasCommunist War in POW Camps 28 January 1953ferneaux81Ainda não há avaliações

- The Justification For Humanitarian Intervention - Will The ContineDocumento25 páginasThe Justification For Humanitarian Intervention - Will The ContinePhilip Kefas TerriAinda não há avaliações

- War CrimesDocumento14 páginasWar CrimesKofi Mc SharpAinda não há avaliações

- PIL MOD 5 ReadingsDocumento12 páginasPIL MOD 5 ReadingsPriyanshi VashishtaAinda não há avaliações

- International Crime: Piracy: Traditionally, in Considered A Breach of The Jus Cogens (The NormsDocumento3 páginasInternational Crime: Piracy: Traditionally, in Considered A Breach of The Jus Cogens (The NormsMissy MissAinda não há avaliações

- In The Events of War, The Law Falls Silent - Ayushi Pandey - 201134845Documento5 páginasIn The Events of War, The Law Falls Silent - Ayushi Pandey - 201134845ayushi21930% (1)

- Movie Review NR 1 - NurembergDocumento6 páginasMovie Review NR 1 - NurembergShannen Doherty100% (1)

- Nuremburg TrialsDocumento18 páginasNuremburg TrialsSahir Seth100% (1)

- (C) D .-As Used in This Section The Term "War Crime" Means Any ConductDocumento29 páginas(C) D .-As Used in This Section The Term "War Crime" Means Any ConductAvishek PathakAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Nuremberg TrialsDocumento10 páginas2 Nuremberg TrialsYogesh KaninwalAinda não há avaliações

- Li Ba JoDocumento14 páginasLi Ba JoWania AbbasiAinda não há avaliações

- The Development of International Criminal Justice Richard GoldstoneDocumento13 páginasThe Development of International Criminal Justice Richard GoldstoneEvelyn TocgongnaAinda não há avaliações

- The Doctrine of InterventionDocumento41 páginasThe Doctrine of InterventionMarius DamianAinda não há avaliações

- PS Final 1Documento4 páginasPS Final 1qmphysicsAinda não há avaliações

- Disarmament-Essay From The War CollegeDocumento17 páginasDisarmament-Essay From The War CollegeJeff WiitalaAinda não há avaliações

- From Nuremberg To The Hague PDFDocumento29 páginasFrom Nuremberg To The Hague PDFXino De PrinzAinda não há avaliações

- Waging War On Wall StreetDocumento64 páginasWaging War On Wall StreetandresopAinda não há avaliações

- U.S. Naval War College Press Naval War College ReviewDocumento14 páginasU.S. Naval War College Press Naval War College ReviewNicolás TerradasAinda não há avaliações

- Arlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsDocumento1 páginaArlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Against 8 Federal AgenciesDocumento13 páginasKen Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Against 8 Federal AgenciesTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Arlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsDocumento1 páginaArlington County Police Department Information Bulletin Re IEDsTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Read House Trial BriefDocumento80 páginasRead House Trial Briefkballuck1100% (1)

- Army Holiday Leave MemoDocumento5 páginasArmy Holiday Leave MemoTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA LawsuitDocumento121 páginasKen Klippenstein FOIA LawsuitTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Ken Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Re Unauthorized Disclosure Crime ReportsDocumento5 páginasKen Klippenstein FOIA Lawsuit Re Unauthorized Disclosure Crime ReportsTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Some Violent Opportunists Probably Engaging in Organized ActivitiesDocumento5 páginasSome Violent Opportunists Probably Engaging in Organized ActivitiesTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- FOIA LawsuitDocumento13 páginasFOIA LawsuitTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Open Records Lawsuit Re Chicago Police DepartmentDocumento43 páginasOpen Records Lawsuit Re Chicago Police DepartmentTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- ICE FOIA DocumentsDocumento69 páginasICE FOIA DocumentsTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- FBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFDocumento5 páginasFBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFWilliam LeducAinda não há avaliações

- Boogaloo Adherents Likely Increasing Anti-Government Violent Rhetoric and ActivitiesDocumento10 páginasBoogaloo Adherents Likely Increasing Anti-Government Violent Rhetoric and ActivitiesTheNationMagazine100% (7)

- Opportunistic Domestic Extremists Threaten To Use Ongoing Protests To Further Ideological and Political GoalsDocumento4 páginasOpportunistic Domestic Extremists Threaten To Use Ongoing Protests To Further Ideological and Political GoalsTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Violent Opportunists Using A Stolen Minneapolis Police Department Portal Radio To Influence Minneapolis Law Enforcement Operations in Late May 2020Documento3 páginasViolent Opportunists Using A Stolen Minneapolis Police Department Portal Radio To Influence Minneapolis Law Enforcement Operations in Late May 2020TheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Social Media Very Likely Used To Spread Tradecraft Techniques To Impede Law Enforcement Detection Efforts of Illegal Activity in Central Florida Civil Rights Protests, As of 4 June 2020Documento5 páginasSocial Media Very Likely Used To Spread Tradecraft Techniques To Impede Law Enforcement Detection Efforts of Illegal Activity in Central Florida Civil Rights Protests, As of 4 June 2020TheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Unrest in Response To Death of George Floyd Threatens Law Enforcement Supporters' Safety, As of May 2020Documento4 páginasCivil Unrest in Response To Death of George Floyd Threatens Law Enforcement Supporters' Safety, As of May 2020TheNationMagazine100% (1)

- DHS ViolentOpportunistsCivilDisturbancesDocumento4 páginasDHS ViolentOpportunistsCivilDisturbancesKristina WongAinda não há avaliações

- DHS Portland GuidanceDocumento3 páginasDHS Portland GuidanceTheNationMagazine100% (2)

- Violent Opportunists Continue To Engage in Organized ActivitiesDocumento4 páginasViolent Opportunists Continue To Engage in Organized ActivitiesTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- CBP Pandemic ResponseDocumento247 páginasCBP Pandemic ResponseTheNationMagazine100% (9)

- "A Global Green Deal," by Mark HertsgaardDocumento5 páginas"A Global Green Deal," by Mark HertsgaardTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

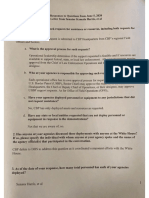

- Responses To QuestionsDocumento19 páginasResponses To QuestionsTheNationMagazine100% (2)

- Sun Tzu PosterDocumento1 páginaSun Tzu PosterTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- The Syrian Conflict and Its Nexus To U.S.-based Antifascist MovementsDocumento6 páginasThe Syrian Conflict and Its Nexus To U.S.-based Antifascist MovementsTheNationMagazine100% (4)

- Algren American ChristmasDocumento2 páginasAlgren American ChristmasTheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- Bloomberg 2020 Campaign Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)Documento11 páginasBloomberg 2020 Campaign Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)TheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- AFRICOM Meeting ReadoutDocumento3 páginasAFRICOM Meeting ReadoutTheNationMagazine100% (1)

- Law Enforcement Identification Transparency Act of 2020Documento5 páginasLaw Enforcement Identification Transparency Act of 2020TheNationMagazine50% (2)

- "The Ins and The Outs," by Betita Martínez, 1967Documento4 páginas"The Ins and The Outs," by Betita Martínez, 1967TheNationMagazineAinda não há avaliações

- The War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionNo EverandThe War after the War: A New History of ReconstructionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Over My Dead Body: Unearthing the Hidden History of American CemeteriesNo EverandOver My Dead Body: Unearthing the Hidden History of American CemeteriesNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (39)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedNo Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (111)

- An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sNo EverandAn Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960sNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentNo EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (8)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldNo EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (1146)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorNo EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (77)

- Pan-Africanism or Pragmatism: Lessons of the Tanganyika-Zanzibar UnionNo EverandPan-Africanism or Pragmatism: Lessons of the Tanganyika-Zanzibar UnionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceNo EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (51)

- Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernNo EverandTwelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (9)

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume INo EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume INota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (78)

- The Consolation of PhilosophyNo EverandThe Consolation of PhilosophyNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (44)

- Compromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. TrumpNo EverandCompromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. TrumpNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (18)

- Franklin & Washington: The Founding PartnershipNo EverandFranklin & Washington: The Founding PartnershipNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (14)

- American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansNo EverandAmerican Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (66)

- Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkNo EverandDarkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the BrinkNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (31)

- Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincNo EverandPeriodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, from Arsenic to ZincNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (137)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNo EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (10)

- Devil at My Heels: A Heroic Olympian's Astonishing Story of Survival as a Japanese POW in World War IINo EverandDevil at My Heels: A Heroic Olympian's Astonishing Story of Survival as a Japanese POW in World War IINota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (33)

- The Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftNo EverandThe Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftAinda não há avaliações