Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Renaissance Ideal

Enviado por

MrMarkitosDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Renaissance Ideal

Enviado por

MrMarkitosDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Renaissance ideal[edit]

Many notable polymaths lived during the Renaissance period, a cultural movement that

spanned roughly the 14th through to the 17th century and that began in Italy in the late

Middle Ages and later spread to the rest of Europe. These polymaths had a rounded

approach to education that reflected the ideals of the humanists of the time.

A gentleman or courtier of that era was expected to speak several languages, play

a musical instrument, write poetry, and so on, thus fulfilling the Renaissance ideal. The

idea of a universal education was essential to achieving polymath ability, hence the

word university was used to describe a seat of learning. At this time universities did not

specialize in specific areas but rather trained students in a broad array

of science, philosophy, and theology. This universal education gave them a grounding from

which they could continue into apprenticeship toward becoming a Master of a specific

field. During the Renaissance, Baldassare Castiglione, in his guide The Book of the

Courtier, described how an ideal courtier should have polymathic traits.[8]

Castiglione's guide stressed the kind of attitude that should accompany the many talents

of a polymath, an attitude he called sprezzatura. A courtier should have a detached, cool,

nonchalant attitude, and speak well, sing, recite poetry, have proper bearing, be athletic,

know the humanities and classics, paint and draw and possess many other skills, always

without showy or boastful behavior, in short, with sprezzatura. The many talents of the

polymath should appear to others to be performed without effort, in an unstrained way,

almost without thought. In some ways, the gentlemanly requirements of Castiglione recall

the Chinese sage,Confucius, who far earlier depicted the courtly behavior, piety and

obligations of service required of a gentleman. The easy facility in difficult tasks also

resembles the effortlessness inculcated by Zen, such as in archery where no conscious

attention, but pure spontaneity, produces better and more noble skill. For Castiglione, the

attitude of apparent effortlessness should accompany great skill in many separate fields.

In word or deed the courtier should "avoid affectation ... (and) ... practice ... a

certain sprezzatura ... conceal all art and make whatever is done or said appear to be

without effort and almost without any thought about it".[8][9]

This Renaissance ideal differed slightly from the polymath in that it involved more than just

intellectual advancement. Historically (roughly 14501600) it represented a person who

endeavored to "develop his capacities as fully as possible" (Britannica, "Renaissance Man")

both mentally and physically.

Você também pode gostar

- Literal TermDocumento2 páginasLiteral TermMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Military CareerDocumento2 páginasMilitary CareerMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- NomenclatureDocumento1 páginaNomenclatureMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Monarchies and NobilityDocumento2 páginasMonarchies and NobilityMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia MathematicaDocumento1 páginaPhilosophiæ Naturalis Principia MathematicaMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- NomenclatureDocumento1 páginaNomenclatureMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Nobiles: Roman Republic Consulship Patrician PlebeiansDocumento1 páginaNobiles: Roman Republic Consulship Patrician PlebeiansMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- The French RevolutionDocumento2 páginasThe French RevolutionMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- The First Bridge (Documento1 páginaThe First Bridge (MrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- NomenclatureDocumento1 páginaNomenclatureMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Origin and History: Etruscan Origins Etruscan HistoryDocumento2 páginasOrigin and History: Etruscan Origins Etruscan HistoryMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Description of The Law: Integral FormDocumento2 páginasQualitative Description of The Law: Integral FormMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Parliamentary RepublicDocumento1 páginaParliamentary RepublicMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Origin and History: Etruscan Origins Etruscan HistoryDocumento2 páginasOrigin and History: Etruscan Origins Etruscan HistoryMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Second LawDocumento1 páginaSecond LawMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Revolutionary WarsDocumento2 páginasRevolutionary WarsMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Description of The Law: Integral FormDocumento2 páginasQualitative Description of The Law: Integral FormMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Second LawDocumento1 páginaSecond LawMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Revolutionary WarsDocumento2 páginasRevolutionary WarsMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Theology Translates Into English From TheDocumento2 páginasTheology Translates Into English From TheMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- The First Bridge (Documento1 páginaThe First Bridge (MrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Revolutionary WarsDocumento2 páginasRevolutionary WarsMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- The French RevolutionDocumento2 páginasThe French RevolutionMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Vedel Simonsen: Lucretius Montfaucon MahudelDocumento2 páginasVedel Simonsen: Lucretius Montfaucon MahudelMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Types of WarDocumento2 páginasTypes of WarMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Theology Translates Into English From TheDocumento2 páginasTheology Translates Into English From TheMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Energy: Produce EntropyDocumento2 páginasEnergy: Produce EntropyMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Vedel Simonsen: Lucretius Montfaucon MahudelDocumento2 páginasVedel Simonsen: Lucretius Montfaucon MahudelMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- Etruscans: T Ʌ S K Ə N IDocumento2 páginasEtruscans: T Ʌ S K Ə N IMrMarkitosAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- NCERT Solutions For Class 6 Maths Chapter 5 Understanding Elementary ShapesDocumento51 páginasNCERT Solutions For Class 6 Maths Chapter 5 Understanding Elementary Shapespriya0% (1)

- GFDGFDGDocumento32 páginasGFDGFDGKelli Moura Kimarrison SouzaAinda não há avaliações

- Implementation of MIL-STD-1553 Data BusDocumento5 páginasImplementation of MIL-STD-1553 Data BusIJMERAinda não há avaliações

- Senior Instrument Engineer Resume - AhammadDocumento5 páginasSenior Instrument Engineer Resume - AhammadSayed Ahammad100% (1)

- Usm StanDocumento5 páginasUsm StanClaresta JaniceAinda não há avaliações

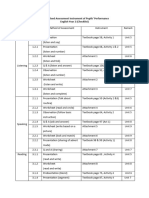

- Penyelarasan Instrumen Pentaksiran PBD Tahun 2 2024Documento2 páginasPenyelarasan Instrumen Pentaksiran PBD Tahun 2 2024Hui YingAinda não há avaliações

- WilkersonDocumento4 páginasWilkersonmayurmachoAinda não há avaliações

- MPhil/PhD Development Planning at The Bartlett Development Planning Unit. University College LondonDocumento2 páginasMPhil/PhD Development Planning at The Bartlett Development Planning Unit. University College LondonThe Bartlett Development Planning Unit - UCLAinda não há avaliações

- Ecosytem Report RubricDocumento1 páginaEcosytem Report Rubricapi-309097762Ainda não há avaliações

- Anomalous Worldwide SEISMIC July 2010Documento130 páginasAnomalous Worldwide SEISMIC July 2010Vincent J. CataldiAinda não há avaliações

- Pathway Foundation T'SDocumento113 páginasPathway Foundation T'SDo HuyenAinda não há avaliações

- Common Ground HSDocumento1 páginaCommon Ground HSHelen BennettAinda não há avaliações

- Tesla Case PDFDocumento108 páginasTesla Case PDFJeremiah Peter100% (1)

- An Inspector Calls Character Notes Key Quotations Key Language & Structural Features Priestley's IdeasDocumento8 páginasAn Inspector Calls Character Notes Key Quotations Key Language & Structural Features Priestley's IdeasPAinda não há avaliações

- Simple & Compound InterestDocumento6 páginasSimple & Compound InterestRiAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Comprehension: Pratyush at Toughest QuestionsDocumento40 páginasReading Comprehension: Pratyush at Toughest QuestionsJaved AnwarAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plans For Sped 101Documento3 páginasLesson Plans For Sped 101api-271266618Ainda não há avaliações

- Resumen CronoamperometríaDocumento3 páginasResumen Cronoamperometríabettypaz89Ainda não há avaliações

- Singapore: URA Concept Plan 2011 Focus Group Preliminary RecommendationsDocumento7 páginasSingapore: URA Concept Plan 2011 Focus Group Preliminary RecommendationsThe PariahAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical OpticsDocumento88 páginasClinical OpticsKris ArchibaldAinda não há avaliações

- Transferring Stock and Sales Data Process SAP StandardDocumento3 páginasTransferring Stock and Sales Data Process SAP StandardrksamplaAinda não há avaliações

- GRC 2018 Mastre RedesignyoursapeccsecurityDocumento40 páginasGRC 2018 Mastre RedesignyoursapeccsecurityPau TorregrosaAinda não há avaliações

- BOC Develop A Strategic Communication Plan of The Transformation Roadmap Phase 2Documento25 páginasBOC Develop A Strategic Communication Plan of The Transformation Roadmap Phase 2Mario FranciscoAinda não há avaliações

- Filipino ScientistsDocumento2 páginasFilipino ScientistsJohn Carlo GileAinda não há avaliações

- Forced Convection Over A Flat Plate by Finite Difference MethodDocumento5 páginasForced Convection Over A Flat Plate by Finite Difference MethodNihanth WagmiAinda não há avaliações

- Master of Business Administration - MBA Semester 3 ProjectDocumento2 páginasMaster of Business Administration - MBA Semester 3 ProjectAnkur SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- 1970 MarvelDocumento2 páginas1970 MarvelFjc SuarezAinda não há avaliações

- Kicking Action of SoccerDocumento17 páginasKicking Action of SoccerM.AhsanAinda não há avaliações

- Penguatan Industri Kreatif Batik Semarang Di Kampung Alam Malon Kecamatan Gunung Pati SemarangDocumento10 páginasPenguatan Industri Kreatif Batik Semarang Di Kampung Alam Malon Kecamatan Gunung Pati SemarangAllo YeAinda não há avaliações

- Group 1 Secb MDCMDocumento7 páginasGroup 1 Secb MDCMPOOJA GUPTAAinda não há avaliações