Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Community and Neighbourhood

Enviado por

JayDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Community and Neighbourhood

Enviado por

JayDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Community Health Nursing, 26:1423, 2009

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0737-0016 print/1532-7655 online

DOI: 10.1080/07370010802605721

Community-Based Perceptions of Neighborhood

Health in Urban Neighborhoods

Janet Hahn Severance

Spectrum Health, Research Department, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Sharon L. Zinnah

Spectrum Health, Healthier Communities Department, Grand Rapids, Michigan

This community-based study explored perceptions of neighborhood health and neighborhood health

characteristics to inform a new urban health neighborhood outreach program utilizing nurse and community health worker teams. Neighborhood residents and representatives from community agencies

described their perceptions of personal health and neighborhood health through questionnaires and focus groups called community conversations. Respondents were more likely to report themselves as

healthy and less likely to report their neighborhoods as healthy. Community conversations common

themes included respect, partnerships and relationships. Results provide guidance for planners of urban neighborhood health initiatives.

This community-based study explored perceptions of neighborhood health to begin to specify the

neighborhood problems that influence health. This study is based on previous research indicating

that individual perceptions of neighborhood characteristics are associated with health behaviors

and outcomes (Gary et al., 2008). Results were used to inform a new urban health neighborhood

outreach program utilizing nurse and community health worker teams. Urban HealthWest

Michigan (UH-WM) is a neighborhood partnership between a local health system and urban

neighborhoods for community health improvement. The purpose of this program is to improve the

overall health of urban neighborhoods in Western Michigan through neighborhood health management and to improve health prosperity in urban populations. The program is funded by a local

health system as part of its efforts to improve the health of the local community. This is one of

many ways that this health system and others attempt to improve community health (Boex,

Cooksey & Inui, 1998; Foreman, 2004).

To better understand the health needs and assets of urban neighborhoods, staff from the

UH-WM program implemented mixed methods of data collection. Researchers conducted interviews, distributed surveys, and facilitated focus groups with interested neighbors and community

stakeholders. Residents and representatives from community agencies described their perceptions

Correspondence should be sent to Janet Hahn Severance, Ph.D., Senior Outcomes Research Manager, Spectrum

Health Research Department, 665 Seward Avenue NW, Suite 110, Grand Rapids, MI 49504. E-mail: janet.severance@

spectrum-health.org

PERCEPTIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH

15

of health and health issues in their neighborhood and their personal life. This insight then influenced program planning.

RELATED LITERATURE

Increasingly, researchers engage respondents where they live, work, or learn, to better understand

community and health issues. Not only does listening provide the basis for trust relationships in

the community, it encourages grassroots participation and problem-solving (McElmurry et. al.,

1990). For example, focus groups have been used to learn that increasing law enforcement, social

support, and structured programs would increase physical activity (Griffin, Wilson, Wilcox, Buck,

& Ainsworth, 2008). Others have used participatory approaches as one of many steps in community health assessment (Idali Torres, 1998). Complex community-based interventions have been

evaluated with ethnographically informed community evaluation. This approach integrates participation of the community with qualitative and survey research (Aronson, Wallis, OCampo,

Whitehead, & Schafer, 2007). Program planners and researchers can better understand the barriers and strategies for health improvement when both qualitative and quantitative methods are used

to gain insight from neighborhood residents (Clark, et. al., 2003; Israel et. al., 2006; Krieger, et.

al., 2002). In addition, eliciting early input from community members helps establish relationships to strengthen partnerships with the neighborhoods (Trettin & Musham, 2000).

URBAN HEALTH-WEST MICHIGAN

The UH-WM program is centered on a registered nurse (RN) and community health worker

(CHW) team that provides a liaison between formal and informal systems of care (McElmurry,

1999, 2003). Nurses are agents between community members and multidisciplinary health care

providers and they work closely with a CHW who is a trusted, vital worker that understands and

relates well to the local community. He or she is familiar with the community and provides critical

bridges to health education and other resources to support patient self-management (Coleman &

Newton, 2005; Dower, Knox, Lindler, & ONeil, 2006). The approach acknowledges the many socioeconomic and cultural barriers to health-seeking behavior. Health promotion programs may

not have impact if individuals are facing fundamental challenges in their social and physical environment (Burgoyne, Coleman, & Perry, 2007). The UH-WM program operates in urban neighborhoods with high levels of health disparities. In these neighborhoods, the RN/CHW team works

with leaders and organizations to support vulnerable populations, including those with a disproportionate burden of illness, underinsured or uninsured, working poor, and those in poverty.

In 2006, a nurse manager was hired and planning began for the UH-WM program to substantially improve the health of urban neighborhoods in West Michigan. The program was to maximize care for those in need through partnering in the neighborhoods and leveraging resources. The

three goals of the UH-WM program are to (a) improve resident health and quality of life through

promotion of health ownership, (b) improve neighborhood residents ability to self-manage their

chronic disease, and (c) enhance overall health status of the neighborhood. In summer of 2008, the

program employed five nurses, six community health workers, and one administrative project

coordinator.

16

SEVERANCE AND ZINNAH

The UH-WM program targets specific neighborhood groups, including schools, churches,

small business, barber shops, beauty shops, corner stores, and grocery stores for lay health promotion. The RN/CHW teams build relationships with neighbors to promote self-reliance and ownership of health outcomes. Staff link residents with the health care system to support programs that

serve specific populations and promote culturally acceptable prevention and disease management

skills. The research on perceptions of neighborhood health is part of the first objective of the

UH-WM program. To increase effectiveness of the neighborhood health interventions, planners

sought to assess health improvement needs, conduct community conversations focus groups, and

assess community strengths.

METHODS

To understand residents perceptions of health in their neighborhood, staff engaged residents and

stakeholders in individual conversations and focus groups. Previous community health projects

have provided successful interventions after listening to residents and acknowledging that the image residents have of their health or neighborhood will affect their actions (Abramson & McKinley, 1999). The neighborhood health surveys and the community conversations focus groups were

approved by the Institutional Review Board of Spectrum Health.

Neighborhood Health Survey Methods

UH-WM nurses and CHWs distributed a written neighborhood health survey to a convenience

sample of community residents. As staff met with neighbors during health fairs or during visits to

neighborhood organizations, they would engage individuals in conversation and then request they

complete the survey. UH-WM staff members were asked to use their judgment about whether or

not the survey should be self-administered or if they should offer to read questions to the individual. The end of the survey included demographic questions, and it began with two multiple choice

questions using a five-point agree or disagree scale. These questions were: (a) How do your rate

your own personal health? and (b) How do you rate the health of your neighborhood? The survey

also included the open-end questions: (c) What do you think are the most important health problems in your neighborhood? and (d) What do you think makes a neighborhood healthy?

Community Conversations Methods

Community conversations were conducted a few months after nurses and community health workers were hired for the UH-WM program. Due to potential mistrust of the term focus group, staff

chose to describe the information gathering sessions as community conversations. UH-WM began

in five neighborhoods that were selected based on assessment of health needs and the potential for

neighborhood partnerships. The neighborhood demographics are described in Table 1. Most neighborhoods have higher percentages of African American or Latino residents than the population of

the city based on the 2000 U.S. Census. Overall, Grand Rapids has seen a rapid rise in the proportion

of Latino immigrants in the past decade, which is not reflected in the 2000 Census. In addition, demographics for Neighborhood 4 are misleading, as only a subset of the large neighborhood is addressed by the UH-WM program. This subset, which is the focus of the UH-WM program, is

lower-income and more racially and ethnically diverse than the entire neighborhood.

17

PERCEPTIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH

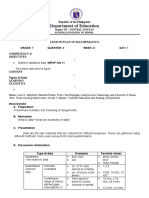

TABLE 1

Neighborhood Demographics Based on 2000 U.S. Census

Neighborhood

Total

Population

Total

Households

Percent

White

Percent

Black

Percent

Hispanic/

Latino

Percent

Other

Race

Percent

Below

Poverty

1

2

3

4

5

Grand Rapids

2,606

4,234

1,177

26,049

6,838

197,800

823

1,566

326

10,518

2,294

73,217

3.80

52.90

26.70

86.70

60.60

62.50

85.90

23.20

27.30

5.50

6.50

19.90

7.40

15.60

39.80

4.10

26.70

13.10

3.00

8.30

6.20

3.70

6.10

4.60

33.50

27.30

28.40

7.58

15.30

15.72

Note.

Grand Valley State University, Community Research Institute (2006).

UH-WM staff recruited neighborhood residents and key stakeholders to participate in the community conversations that were held in the neighborhood in donated space. Over 150 individuals

participated in a total of 12 community conversations, with two completed in three of the neighborhoods and three completed in the remaining two neighborhoods. In each neighborhood, the

first community conversation was facilitated by a member of a local business leadership training

program project team. This is a local organization that provides opportunities for business professionals to expand their leadership skills. The participants were divided into smaller groups with

preassigned recorders, and each group answered two or three of the six questions. After discussion, each group would report responses and other participants were able to contribute their comments. Program staff later wrote notes from the conversations based on the notes of each scribe.

Additional community conversations in each neighborhood were conducted by the RN/CHW

team assigned to that neighborhood.

Research staff distilled the responses through thematic coding using a simple word processing

table format (Hahn, 2008; Yen, Scherzer, Cubbin, Gonzalez, & Winkleby, 2007). The six questions were:

Question 1. When you think about health, what comes to mind?

Question 2. When you think about your neighborhood, what comes to mind?

Question 3. How can we improve health in the neighborhood?

Question 4. What will keep us from improving the healthcare in the neighborhood?

Question 5. How can the community health workers and nurses help our neighborhood?

Question 6. What is the best way to communicate with the neighborhood?

NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH SURVEY RESULTS

The neighborhood health survey was completed by 164 individuals. Respondents were from all

five neighborhoods. The race of the respondents was Black = 44%; White = 41%; Hispanic/Latino

= 11%; other = 4%. Sixty-four percent of respondents were women and 36% were men. The respondents reflected a wide variety of ages with the following percentages: 1418 years = 2.6%;

1929 years = 17.8%; 3039 years = 15.8%; 4049 years = 23.7%; 5059 years = 25%; 6069

years = 9.2%; and 70 year and over = 5.9%.

18

SEVERANCE AND ZINNAH

FIGURE 1 Personal and neighborhood health ratings from neighborhood health survey, n = 164, Pearson Chi

Square p < .01.

When asked about their personal health, respondents were more likely to report themselves as

healthy and less likely to report their neighborhoods as healthy. As shown in Figure 1, over twice

as many respondents described their personal health as healthy (24.4%) while only 9.2% indicated

their neighborhood was healthy. Similarly, 23.8% of respondents indicated they were unhealthy

and fully 37.4% indicated their neighborhood was unhealthy.

The questionnaire also included the multiple-response, open-ended question, What do you

think are the most important health problems in your neighborhood? Over 70 respondents listed

specific health conditions including frequent responses of diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, and asthma. Twenty-eight percent of respondents (46 of 164) indicated substance abuse was

the most important health problem. Approximately one out of ten respondents listed obesity (18),

medical access (17), and nutrition (16) as the most important health problem in the neighborhood.

Eight percent of respondents (13) indicated the trash, stray animals, or pollution in the neighborhood was the most important health problem.

As a follow-up to the question regarding neighborhood health problems, residents answered

the question What do you think makes a neighborhood healthy? Responses were grouped into

the following categories: strong sense of community (30), clean environment (27), activities (22),

nutrition (18), and medical access (13).

COMMUNITY CONVERSATIONS RESULTS

The 12 community conversations were organized using the same questions in order to yield comparable results. The results for each question are described below and detailed in corresponding

PERCEPTIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH

19

tables. Common categories among three of the groups were trust, education and transportation. At

least two of the groups included respect, cost, access, safety, partnerships, and relationships as

common categories.

Question 1, When you think about health, what comes to mind?

Participants provided 66 separate responses on what comes to mind when they think of health.

Common answers included access, cost, healthy lifestyles, lack of knowledge, mistrust, and

safety. Table 2 provides specific examples of statements for each category.

Question 2, When you think about your neighborhood,

what comes to mind?

Participants provided 75 separate responses on what comes to mind when they think about the

neighborhood. Listed alphabetically, common answers included churches, crime, diversity, hopelessness, the need for a sense of community, poverty, and an unsafe environment. Table 3 provides

specific examples of statements for each category.

TABLE 2

Summary Responses to Question 1, When you Think About Health,

What Comes to Mind?

Category

Sample Statement

Access

Cost

Healthy lifestyles

Lack of knowledge

Mistrust

Safety

Teaching the health system

Transportation

Difficulty accessing health care. Where can I get it? How can I afford it?

Choosing between medications, bills and food

Poor diet, no access to fresh fruits and vegetables

Need more education on health

Fear and mistrust of healthcare system

Physical and emotional safety

Community members can educate healthcare providers as well.

Transportation access

TABLE 3

Summary Responses to Question 2, When you Think About Your Neighborhood,

What Comes to Mind?

Category

Sample Statement

Churches

Crime

Diversity

Churches walk along with people to help

Substance abuse/violence/gangs/neglect

Diverse population of residents (homeowners, renters, college students, children,

parents, senior citizens)

Lack of opportunities and optimism

Residents not involved in planning

Lower levels of income, education, and employment

Break-ins, speeding, unleashed dogs

Hopelessness

Need sense of community

Poverty

Unsafe

20

SEVERANCE AND ZINNAH

Question 3, How can we improve health in the neighborhood?

Participants provided 72 separate responses on how to improve health in the neighborhood. Improved access to health care, health promotion, and transportation were seen as important to improving health. In addition, neighbors sought culturally sensitive approaches to health and health

care coordination. Neighborhood health could also be improved through education, health services, partnerships, and support groups. Table 4 provides specific examples of statements for each

category.

Question 4, What will keep us from improving the health care

in the neighborhood?

Participants provided 69 separate responses on what will keep UH-WM and other programs from

improving the health care in the neighborhood. Responses included bureaucracy, cost, illiteracy,

lack of information, lack of relationships, mistrust, lack of transportation and not prioritizing.

Table 5 provides specific examples of statement for each category.

TABLE 4

Summary Responses to Question 3, How can we Improve Health in the Neighborhood?

Category

Sample Statement

Access to health care

Access to healthy foods and activities

Address language/culture

Coordination of care

Education

Neighborhood health services

Partner

Support groups

Transportation

Increase access to care

Access to health foods (grocery store in the neighborhood)

Address language barriers

Coordinate agencies

Provide information and health information

Bringing healthcare services and systems to the residents

Need to work together

Support groups and stress management

Address transportation barriers

TABLE 5

Summary Responses to Question 4, What Will Keep us From Improving

the Healthcare in the Neighborhood?

Category

Bureaucracy

Cost

Illiteracy

Lack of information

Lack of relationships

Mistrust

Not prioritizing

Lack of transportation

Sample Statement

Rules of Medicaid

Limited financial resources

Health literacy and computer literacy

Lack of information and education

Lack of communication and relationship building in neighborhood

Trust takes awhile to build. Cant assume its there

Misuse of resources

Not addressing transportation barriers

PERCEPTIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH

21

Question 5, How can the community health workers and nurses

help our neighborhood?

Participants provided 81 separate responses on how the CHWs and nurses could help their neighborhood. Neighbors shared that the staff should communicate, educate, and provide referrals.

They also shared that while providing neighborhood health options, staff should be respectful of

individual residents and partner with the neighborhood. Table 6 provides specific examples of

statement for each category.

Question 6, What is the best way to communicate with

the neighborhood?

Participants provided 79 separate responses on how best to communicate with the neighborhood.

Relationships and visibility were mentioned most frequently, with respect, incentives, listening,

media, open dialogue and trust as other common answers. Table 7 provides specific examples of

statement for each category.

TABLE 6

Summary Responses to Question 5, How can the Community Health Workers

and Nurses Help our Neighborhood?

Category

Sample Statement

Communicate

Educate

Partner

Provide neighborhood health options

Refer

Respect

Encourage neighbor-to-neighbor discussions about healthcare

Provide information, raise awareness about activities or events in the neighborhood

Health outreach and relationships

Health services, nutritious food, screenings, and support groups

Link neighbors to resources

Understand neighbors perspective of health and health care

TABLE 7

Summary Responses to Question 6, What is the Best Way to Communicate

With the Neighborhood?

Category

Incentives

Listen

Media

Open dialogue

Relationships

Respect

Trust

Visibility

Sample Statement

Incentives to get people to come to programs.

Find out what the community members want from the healthcare experience.

Use media (radio, television, newspaper, fliers).

Communicate with us and us with each other.

Put in time. It takes time to build relationships.

Communicate with respect, without prejudice and attitude.

Need trust through building relationship.

Be visible in the community, get involved in local activities.

22

SEVERANCE AND ZINNAH

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study was community-based and exploratory to provide information for UH-WM program

staff. The samples of respondents to the neighborhood health survey and the community conversation participants were convenience samples, and therefore the results are not representative of all

neighborhoods residents. Respondents to the neighborhood survey were found in public places

such as community events, so were likely to be healthier than the neighborhood as a whole and

less likely to be individuals who worked during the day. Program staff faced difficulties in recruiting participants to the community conversations due to inconsistent methods of communication,

lack of trust, timing of the conversations, or weather. As a result, in some neighborhoods there

were more stakeholder participants such as community leaders or employees of local organizations than residents. For the purposes of program planning, the results served their purpose of providing qualitative insight into perceptions of health. However, one cannot use these results to

make valid conclusions regarding neighborhood differences or change over time.

DISCUSSION

Results from the neighborhood health survey and the community conversations provide insight

for community health nurses who are planning and delivering health outreach services. Perception

of neighborhood health in urban, racially diverse, low-income neighborhoods can help enlighten

leaders and guide planning decisions. For example, professionals from higher income neighborhoods may not be aware that the excessive trash in a neighborhood is widespread and seen as a

health problem. Unless staff spend substantial time in the neighborhoods or listen to residents, the

impact of trash in a neighborhood may not be considered in planning services. Similarly, the perception of the neighborhood as significantly less healthy than the self-perceived health of the respondent is informative for those who plan services. It is likely that over time, the stress of perceiving ones neighborhood as unhealthy may also influence an individuals health.

The community conversations presented common themes including respect, partnerships, and

relationships. These interpersonal issues are clearly seen by respondents as vital to health. Community nurses and other health professionals must work to establish trusted relationships to address neighborhood health needs. Cost and access are widely recognized as health issues for

low-income, racially diverse individuals, but safety is not as widely recognized as a health issue. It

is difficult to exercise outside if one fears for ones safety. It is difficult to travel to a doctors appointment if it means waiting for a bus in an unsafe area. This sense of safety likely contributes to

higher chronic stress and related health issues.

CONCLUSION

The insight gained by learning neighborhood perceptions of health will help health professionals

plan interventions that are more effective in improving community health. This model of engaging

community members could be used by other programs to inform efforts and the results may provide guidance for planners of urban neighborhood health initiatives.

PERCEPTIONS OF NEIGHBORHOOD HEALTH

23

REFERENCES

Abramson, R., & McKinley, J., (1999). Chicago health connection: Developing community leadership in maternal and

child health in primary health care in urban communities. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Aronson, R. E., Wallis, A. B., OCampo, P. J., Whitehead, T. L., & Schafer, P. (2007). Ethnographically informed community evaluation: a framework and approach for evaluating community-based initiative. Maternal Child Health Journal,

11(2), 97109.

Boex, J. R., Cooksey, J., & Inui, T., (1998). Hospital participation in community partnerships to improve health. Joint

Commission Journal of Quality Improvement, 24(10), 541548.

Burgoyne, L., Coleman, R., & Perry, I. J. (2007). Walking in a city neighborhood, paving the way. Journal of Public

Health, 29(3), 222229.

Clark, M. J., Cary, S., Diemert, G., Ceballos, R., Sifuentes, M., Atteberry, I., et al. (2003). Involving communities in community assessment. Public Health Nursing, 20(6), 456463.

Coleman, M. T., & Newton, K. S. (2005). Supporting self-management in patients with chronic illness. American Family

Physician, 72(8), 15031510.

Dower, C., Knox, M., Lindler, V., & ONeil, E. (2006). Advancing community health worker practice and utilization: The

focus on financing. San Francisco, CA: National Fund for Medical Education.

Foremen, S., (2004). Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York: Improving Health in an Urban Community. Academic Medicine, 79(12), 11541161.

Gary, T. L., Stafford, M. M., Berzoff, R. B., Ettner, S. L., Karter, A. J., Beckles, G. L., et al. (2008). Percepetion of neighborhood problems, health behaviors, and diabetes outcomes among adults with diabetes in managed care. Diabetes

Care, 31, 273278.

Grand Valley State University, Community Research Institute. (2006). Neighborhood demographics based on 2000 U.S.

Census. Retreived October 9, 2006, from the Community Research Institute Web site http://www.cridata.org/profiles/

neighborhood/index.html

Griffin, S. F., Wilson, D. K., Wilcox S., Buck J., & Ainsworth B. E. (2008). Physical activity influences in a disadvantaged

African American community and the communities proposed solutions. Health Promotion Practice, 9, 180190.

Hahn, C. (2008). Doing qualitative research using your computer: A practical guide. London: Sage.

Idali Torres, M. (1998). Assessing health in an urban neighborhood: community process, data results and implications for

practice. Journal of Community Health, 23, 21126.

Israel, B. A., Schultz, A. G., Estrada-Martinez, L., Zenk, S. N., Viruell-Fuentes, E., et al. (2006). Engaging urban residents

in assessing neighborhood environments and their implications for health. Journal of Urban Health, 83, 52339.

Krieger, J., Allen, C., Cheadle, A., Ciske, S., Schier, J. K., Senturia, K., et al. (2002). Using community-based participatory

research to address social determinants of health: Lessons learned from Seattle Partners for Health. Health Education

Behavior, 29, 361382.

McElmurry, B. J. (1999). Introduction to Primary Health Care in urban communities. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

McElmurry, B. J. (2003). The nursecommunity health advocate team for urban immigrant primary health care. Journal of

Nursing Scholarship, 35, 275281.

McElmurry, B. J., Swider, S. M., Bless, C., Murphy, D., Montgomery, A., Norr, K., et al. (1990). Community health advocacy: Primary health care nurse-advocate teams in urban communities. NLN Publications, 41(2281), 117131.

Trettin L., & Musham C. (2000). Using focus groups to design a community health program: what roles should volunteers

play? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 11(4), 444455.

Yen, I. H., Scherzer, T., Cubbin, C., Gonzalez, A., & Winkleby, M. A. (2007). Womens perceptions of neighborhood resources and hazards related to diet, physical activity, and smoking: focus group results from economically distinct

neighborhoods in a mid-sized U.S. city. American Journal of Health Promotion, 22(2), 98106.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- DIT 3 Year 1st YearsDocumento24 páginasDIT 3 Year 1st YearsInnocent Ramaboka0% (1)

- Veterinary InformaticsDocumento5 páginasVeterinary InformaticsRonnie DomingoAinda não há avaliações

- Unit IV: Perspective of Managing Change: Maevelee C. CanogoranDocumento27 páginasUnit IV: Perspective of Managing Change: Maevelee C. Canogoranfe rose sindinganAinda não há avaliações

- Brandon Walsh: Education Bachelor's Degree in Business Management Coursework in Mechanical EngineeringDocumento1 páginaBrandon Walsh: Education Bachelor's Degree in Business Management Coursework in Mechanical Engineeringapi-393587592Ainda não há avaliações

- CAPE Communication Studies ProgrammeDocumento27 páginasCAPE Communication Studies ProgrammeDejie Ann Smith50% (2)

- Reviewer Cri 222Documento10 páginasReviewer Cri 222Mar Wen Jie PellerinAinda não há avaliações

- Context in TranslationDocumento23 páginasContext in TranslationRaluca FloreaAinda não há avaliações

- Gec 6: Science, Technology & Society Handout 2: General Concepts and Sts Historical DevelopmentsDocumento8 páginasGec 6: Science, Technology & Society Handout 2: General Concepts and Sts Historical DevelopmentsJoan SevillaAinda não há avaliações

- Doctrine of The MeanDocumento2 páginasDoctrine of The MeansteveAinda não há avaliações

- LESSON PLAN Periodic TableDocumento12 páginasLESSON PLAN Periodic TableUmarFaruqMuttaqiinAinda não há avaliações

- Patient Centered CareDocumento11 páginasPatient Centered CareAnggit Marga100% (1)

- Samit Vartak Safal Niveshak March 2016Documento7 páginasSamit Vartak Safal Niveshak March 2016Jai SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Report in Profed 2Documento16 páginasReport in Profed 2Gemwyne AbonAinda não há avaliações

- Educ 201 Module 1Documento21 páginasEduc 201 Module 1Malou Mabido RositAinda não há avaliações

- Sabour Agri JobDocumento8 páginasSabour Agri JobBipul BiplavAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study 9Documento1 páginaCase Study 9Justin DiazAinda não há avaliações

- ENCO 1104 - MQA-02-Standard Course OutlinesDocumento8 páginasENCO 1104 - MQA-02-Standard Course OutlineslynaAPPLESAinda não há avaliações

- Science Without Religion Is Lame Religion Without Science Is BlindDocumento2 páginasScience Without Religion Is Lame Religion Without Science Is Blindgoodies242006Ainda não há avaliações

- Jurnal KPI (Kel. 7)Documento2 páginasJurnal KPI (Kel. 7)Muhammad Faiz AnwarAinda não há avaliações

- PowerPoint Slides To PCS Chapter 01 Part BDocumento22 páginasPowerPoint Slides To PCS Chapter 01 Part BSudhanshu VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsDocumento2 páginasDepartment of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsShiera SaletreroAinda não há avaliações

- 3rd Grade Lesson PlanDocumento2 páginas3rd Grade Lesson Planapi-459493703Ainda não há avaliações

- WK 3 Sovereignties of LiteratureDocumento12 páginasWK 3 Sovereignties of LiteratureEdgardo Z. David Jr.100% (1)

- Baylor Law School 2013-2015 Academic CalendarDocumento2 páginasBaylor Law School 2013-2015 Academic CalendarMark NicolasAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1 Lesson Plan RationaleDocumento33 páginasAssignment 1 Lesson Plan Rationaleapi-320967641Ainda não há avaliações

- CCSSMathTasks Grade4 2014newDocumento79 páginasCCSSMathTasks Grade4 2014newRivka ShareAinda não há avaliações

- Kristofer AleksandarDocumento69 páginasKristofer AleksandarJelena BratonožićAinda não há avaliações

- Amu Intra 2016 PDFDocumento13 páginasAmu Intra 2016 PDFSonali ShrikhandeAinda não há avaliações

- Alberto Perez Gomez - Architecture As DrawingDocumento6 páginasAlberto Perez Gomez - Architecture As DrawingmthgroupAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Organizational Citizenship BehivaorDocumento18 páginas2 Organizational Citizenship BehivaorShelveyElmoDiasAinda não há avaliações