Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Hetzler Causality

Enviado por

Bruno De BorDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hetzler Causality

Enviado por

Bruno De BorDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ruin

Causality:

Time

and

Ruins

Florence M. Hetzler

Abstract-A ruin is defined as the disjunctiveproductof the intrusionof nature upon an edifice

without loss of the unity producedby the humanbuilders. Ruin time, proposedas the principal

cause of ruin, serves also to unify the ruin. In a ruinthe edifice, the human-madepart, andnature

are one and inseparable;an edifice separatedfrom its natural setting is no longer part of a ruin

since it has lost its time, space and place. A ruin has a signification different from something

merely human-made.It is like no other work of art and its time is unlike any other time.

I. INTRODUCTION

shadow, no antiquity, no mystery, no

picturesque and gloomy wrong, nor

anything but a commonplace posterity,

in broad and simple daylight, as is

happily the case with my dear native

land. Romance and poetry, ivy, lichen

and wallflowers need ruin to make

them grow [3].

Timepast and tine future

What might have been and what has

been

Point to one end, which is always

present....

"BurntNorton"

-T.S. Eliot

Many have written about ruins from the

viewpoint of Romanticism, as Rose

Macauley did [1]; others have viewed

ruins as monuments that have worth

because of their age, the history they

express or the memories they recall; and

still others, such as Alois Riegl [2], have

viewed them as objects of contemplation,

especially in the case of religious

monuments.

Many paintings have incorporated

ruins. Among these paintings, one might

cite some that appeared on the wall next

to Isaac Newton's Principia (dated 1687,

the year of its publication) in November

and December 1986 at the Morgan

Libraryin New York: ClassicalRuins with

Statues of Hercules and the River Nile and

Figures by Giovanni Pannini (16911765), The Figures Among the Ruins of a

Church in Prague by Roelandt Savery

(1576-1639), Capriccio with a Round

TowerandRuinsby a Lagoon by Canaletto

(1697-1768), View of the Temple of

Neptune and the Basilica at Paestum by

Hubert Robert (1733-1808) as well as

various ruins at Paestum by Piranesi. One

also finds copies of ruins in many public

parks and private gardens.

Even Nathaniel Hawthorne spoke of

needing time and ruins for nurturing

romance and poetry. He wrote in 1859 in

the preface to The Marble Faun:

II. DEFINING A RUIN

My own view of ruins is quite different.

As I have stated in the past [4], I believe

that ruins may be considered works of art

just as works of music, painting, etc., may

be. A ruin, however, is a special work of

art. It includes the human-made and the

nature-made and has its own time, place,

space, life and lives. Ruin time is immanent

in a ruin and this time includes the time

when it was first built, that is, the time

when it was not a ruin; the time of its

maturation as a ruin; the time of the

birds, bees, bats and butterflies that may

live in or on the ruin; the cosmological

time of the land that supports it and is

part of it and will take back to itself the

man-made part eventually; as well as the

sidereal time of the stars, sun and clouds

that shine upon it, shadow it and are part

of it. A ruin is the disjunctive product of

the intrusion of nature upon the humanmade without loss of the unity that our

species produced.

A ruin is thus a combination of various

factors: of the art, science and technology

that produced the structure in the first

place; of nature, including earth, rain,

snow, wind, frogs and lizards; and of

time, which causes an edifice to become a

ruin. Time is the intrinsic cause of a ruin

as a ruin. One should also note that all the

senses save taste are employed in the

appreciation of a ruin [5].

The 'ruining' may be started by human

or natural causes but the maturation

process must be done by nature in ruin

time. Otherwise there is only devastation

and there is no unity forming the ruins. A

ruin also has a uniqueness that comes

from the people who made that which is

No authorwithouta trialcan conceive

of the difficultyof writinga romance

about a country where there is no

FlorenceM.Hetzler(philosopher,

educator),Chateau

Rochambeau,

Apt.6L,Scarsdale,NY 10583,U.S.A.

Received23 June 1986.

? 1988 ISAST

Pergamon Journals Ltd.

Printed in Great Britain.

0024-094X/88

$3.00+0.00

~" 'V,

~

.. :.:

.---

...

Fig. 1. Castleof SiegfrieddeRachewiltz,Tschengls,Italy.Overtimethiscastlehasbecomemoreor

less integratedwithnature.

LEONARDO, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 51-55, 1988

being ruined, from the nature that is

ruining it and the nature that is integral to

it, as well as from the kind of percipient

who views or otherwise experiences it. A

ruin has a maturation time and even a

cycle of maturation times.

Initially the architectural part may be

seen as beautiful. After a period of change

this beauty of architecture will disappear

and a new architecture occurs, one not

intended by those who made the original.

With nature's changes there is a new

beauty created by nature in ruin time,

namely, ruin beauty. A ruin is, indeed, a

new category of being. As more of the

changes of nature and the different times

of being that constitute it occur, it may be

considered, at different times, either a

...

work of art, albeit a different kind of

work of art, or again merely a ruin [6].

The castle of Siegfried de Rachewiltz,

the grandson of Ezra Pound, provides a

good example of what I term a ruin (Fig.

1). Time was needed for this castle,

located at Tschengls in the Italian Tyrol,

to become more or less integrated with

the nature that constitutes it. In fact, one

cannot say where that nature ends. One is

aware of clouds, snow-capped mountains

and wildflowers; the sound of hand

scythes as the farmers cut the hay, the

sound of cowbells as the cows go down a

path near the castle; the movement of the

black-and-white cows and the maids who

lead them down the path; the musty smell

within the walls and the touch of the

of these

Fig.2. Partof theruinsof Persepolis,Iran,theformerpalaceof DariusandXerxes.Perception

as well

ruinsincludestheexperienceof oppressiveheatandthepresenceof sheep,goatsandshepherds

as theedificeitself.

52

Hetzler, Ruin Time and Ruins

multi-textured stones that are part of the

ruin's architecture. One is also aware of

the fact that the castle is placed on top of a

mountain and stands as a presence in the

shape of a great ship. Instead of being

surrounded by water, its location is

enhanced by fir trees and the sound of

birds. The walk up the mountain to the

ruin is also part of the ruin.

This castle is a ruin, whereas Schloss

Brunnenberg, in Merano, Italy, where

Siegfried de Rachewiltz lives with his

family, is a ruined ruin. The latter was not

allowed to lead its life of ruining but was

restored. It has its own beauty and it may

be a work of art, but ruin time has not

allowed it to have the being of a ruin or

ruin beauty. Each being has its own time

and each ruin has its own ruin time-a

time that connects with the sky and earth

much as do the earthworks of Walter De

Maria, whose LightningField (completed

1977) draws the attention of the viewer

not just to the poles that connect with the

earth and sky but to the elements that

change around these poles [7]. This earth

art is not a ruin, but it is one with the

earth. It has earth-art time but not ruin

time [8]. One might also refer to Peter

Hutchinson's Threaded Calabash, an

example of underwater earth art. This

work, done in 1969 in Tobago, West

Indies, was made of rope and five

calabashes and was placed upon a coral

reef in water 30 feet deep. But it, too, did

not have ruin time. Because of the

ephemerality and the lack of tenacity of

its material, this work has probably

disintegrated. It is and never can be a ruin

for another reason. It does not have the

required size.

A ruin must initially be a work of

architecture, even if that is a humble

stone abode, as in the case of the beehive

dwellings on the Garvellach Islands in

Scotland's Inner Hebrides or a stone barn

on Wolfe Island in the St. Lawrence River

in Canada. A ruin may be under the water

and to see it one has to swim. Such a ruin

is located under the sea near the northeast

coast of Crete. It is the former town of

Driros that fell into the sea. One may

swim over and in the ruins of old houses,

and real fish may also swim over the

dolphin mosaics that are still visible on

the floors of the houses. A ruin may be

without a roof or it may have Gothic

arches that remind one of whale bones

vaulted against the sky and allowing the

sun to fill the ruin and to shine on the

walls' reliefs. The sun becomes part of the

ruin. Beyond the frames of these bones

one sees the clouds, and the ruin-that of

a Carmelite convent whose original

harmony was jolted by the earthquake of

1755 in Lisbon, Portugal, and which

submitted itself to ruin time-has a kind

of spatially infinite dimension.

In considering a ruin, one must also

acknowledge subjective time, the time of

the percipient. This time may be affected

by the time of day-dusk or dawn,

moonlight or sunshine; by the mood of

the percipient; and even by the temperature, as, for example, the intense cold of

the island of Danskoya, the location of

the Arctic ruins of the factory built by the

balloonist Salomon August Andree while

preparing for his unsuccessful balloon

trip over the North Pole. The ruins of

Volubilis in Morocco and of Persepolis in

Iran cannot be perceived without the

experience of oppressive heat. The photograph of a part of the ruins of Persepolis

(Fig. 2) was taken in such heat that I had

to use a shepherd's head-covering to hold

the camera. The dry heat was not only

part of my perception of the ruin but had

been part of that ruin since 330 B.C. when

Alexander the Great and his hordes

started the destruction of this palace

which through nature and ruin time has

become a ruin with beautiful shapes that

share in its insistent co-creation. The

lions standing guard, the stairs with the

reliefs on the walls next to them, the

cuneiform writing and even the column

barely discernible in the distance all give

shape to one another and to the ruin as a

totality. The blues and the pinks of the

marble shine in the light of the oppressive

heat. The texture of the marble gives this

ruin a uniqueness. Sheep, goats and

shepherds are parts of this ruin. Peter

Brook also added a new dimension to the

ruin when he presented his play Orghast

at the time of the Shah's celebration

there. The ruin has a unique ruin time just

as the time that constitutes other ruins is

different, as in the case of Borobudur on

the island of Java in Indonesia or the

Buddhas in Bamyan in northern

Afghanistan where the material is a clay

mountain. In Bamyan, as in Michael

Heizer's earth art, the art is carved out of

the land and is part of it.

A ruin, the architectural part and the

earth part, has an integrity that resonates

far [9]. The architectural part is one with

the land. It is also one with the heavens to

which it is open. On the island of Samos

in Greece there is an edifice called

"Twelve Doors". Trees grow out of this

former temple and basilica and shade the

human-made part. Burned grass, a dry

gully and grapevines distinguish this ruin.

The time of the ruining process includes

the time of the trees within the ruin.

The process of the ruination has a

unique time. The Temple of Dendur in

the Metropolitan Museum in New York

may be considered for aesthetic and

Fig. 3. MacchuPicchu,Incacity in the PeruvianAndes.Thetimeof this city includesits timeas a

non-found

city-its timeburiedin the earth.

historical reasons, but it is not a ruin. It is

a ruined ruin because it has lost its own

ruin time, space and place. Ruins cannot

be moved; their locus is a component

whether it be that of the Ring of Brodgar

in the Orkneys or the Stones of Callanish

on the island of Lewis in Scotland's

Hebrides. Imagine removing the standing

stone alignments of Corsica to the Nile!

And where would one put Karnak or

Luxor? If the H.M.S. Breadalbane, the

British ship that took part in the Franklin

expedition and sank in the Arctic ice,

were brought up, it would not be a ruin.

But Franklin's camp on Beechey Island in

the Arctic is a ruin.

Ruins must also be semioticallydifferent

from what they were before they became

ruins. If one visits the Parthenon, one

should not feel the need to bring an oil

lamp for Athena. The Parthenon stands

on its own and signifies itself. The same is

abundantly true of the formerly lost city

of Macchu Picchu (Fig. 3). When Hiram

Bingham found this city in 1911 it was

covered with vines and many kinds of

vegetation [10]. The time of this city

includes its time as a non-found city-its

time buried in the earth and covered with

the being of the earth. When one

approaches it now as a visible city, one

sees the configurations that have been

revealed by the removal of what kept it

from view. This now-visible ruin includes

the sound of the Urubamba River that

has been rushing by for centuries, the

Fig. 4. Menhirsof Pelaggiu,Corsica,Italy.Thestandingstonesarewellon theirwayto a peaceful

returnto theearth.

Hetzler, Ruin Time and Ruins

53

Fig. 5. Deception Island (Antarctica) whaling station destroyed by volcanic eruption. In the case of

andthenature-made

do nothavetheunitybroughtaboutby ruintime.

devastation,thehuman-made

gigantic presence of the mountain Huayna

Picchu next to it and the flowers, lichen

and algae on the rhomboidal windows

that look out upon the immense Peruvian

landscape. The Andean terraces here that

were made by the Incas long ago are not

considered as places for raising crops.

These ridges are part of the rhythm and

shape of the ruin and have a new

significance, too, as does the whole ruin,

which often is shrouded in white mist that

makes the ruin invisible, especially in the

morning. When the sun pierces the mist,

then the buildings, lizards and spiders can

be seen as parts of the whole. All aspects

of this city ruin seem to grow together and

may return to the earth together. There is

still the tenacity of the stone and its

struggle with the vegetation. There is a

persistent resistance of stone and shapes

to nature.

III. RUIN TIME

Time creates the ruin by making it

something other than what it was,

something with a new significance and

signification, with a future that is to be

compared with its past. Time writes the

future of a ruin. Ruin time creates the

future of a ruin, even the return of the

man-made part to the earth, which will

eventually claim what is its propertythat is, that from which the architectural

part is made. As articulated by Georg

Simmel:

Whenwe speakof'returninghome',we

meanto characterizethe peacewhose

moodsurroundstheruin.Andwe must

characterizesomethingelse: our sense

that these two world potencies-the

54

striving upward and the sinking

downward-are workingserenelytogether,as we envisagein theirworking

a pictureof purely naturalexistence.

Expressingthis peace for us, the ruin

orders itself into the surrounding

landscapewithout a break, growing

together like a tree ... [11].

One understands what Simmel meant if

one considers the menhirs of the site of

Pelaggiu in Corsica (Fig. 4). The standing

stones are well on their way to a peaceful

return to the earth. Ruin time creates a

peace that is absent in the case of a

devastation, where the human-made and

the nature-made are not one but separate.

Devastations do not have the ruin time

necessary for maturation [12]. Coventry

Cathedral's remains are not ruins;there is

no unity. An excellent example of a

devastation can be found on Deception

Island in Antarctica (Fig. 5), despite the

fact that it has as its setting one of the

most beautiful places I have ever seen.

The shores of this volcanic island help

form a bay which is actually the crater of

a volcano which erupted and destroyed a

large whaling station. The buildings and

machinery of the station, though partially

covered with black volcanic ash and

enhanced by penguins, seals, snow,

icebergs and volcanic steam, are a part of

the devastation. There has been no

causality of ruin time that would allow

the human-made to be integrated with the

greatness of nature.

Ruin time unites. It is beyond historical

time. It includes the biological time of

birds and moss. In it is the synergy of the

various times of the various beings

involved in a ruin. The part of China's

Great Wall that is visited by tourists is not

Hetzler, Ruin Time and Ruins

a ruin. Ruin time has been removed by

too much restoration. If, however, one

takes the train from Peking to Ulan

Bator, Mongolia, one can see the Great

Wall as a beautiful ruin, sometimes

surrounded by swirls of sand in sandstorms, and surrounded by camels and

farm carts as well as by wild horses. The

Great Wall includesthe landscapethrough

which it serpentines. And if one were in a

plane flying over the wall, one would

perceive more globally the integrity of the

ruin, that is, the conjunction of the wall

and the land dotted by people, animals

and sparse vegetation. One would see

with certitude that a ruin may be defined

as the disjunctive product of the intrusion

of nature without loss of the unity that a

person or people produced.

Size is important to the appreciation of

a ruin; so too its shape, not only of the

architectural part but of the natural part.

The approach to a ruin may also be

included in the ruin. To get to Borobudur,

a former Buddhist temple, one walks

through a small village. One can smell the

food that is being cooked on the spot.

Morning mist mingles with the smoke

from the small village houses. One does

not think of this as a place where one is

called to worship any more than one does

in the Buddhist caves at Ajanta, Ellora,

Elephanta or Bagh in India. In Borobudur

and the caves there is size, time, shape,

architecture and nature. They are real

ruins.

IV. RUIN BEAUTY

Since nature is involved in a ruin, I

believe that ruin beauty comes closer to

the sublime and the ineffable than either

nature's beauty or artistic beauty considered alone [13]. In a ruin the beauty of

nature intersects with man-made beauty

in a unique manner. Both natural beauty

and artistic beauty are more limited and

qualified when taken individually than

when considered in this new form,

namely, ruin beauty. Together they yield

a new kind of beauty and a new time. One

might call the aesthetics of ruins the

aesthetics of the sublime par excellence,

since it includes nature and the humanmade in a natural setting [14].

V. RUIN ART

The ruin brings together nature, the

human-made and the human being-all

unified in ruin time. There is a new

integrity and a new time-a confluence of

naturetime, human-madetime and human

time. There is not just the juxtaposition of

these times but a unity of all three, a unity

that exists no place else in the universe

and certainly no place else in the art

world. This time defies definition, which

is one of the reasons a ruin defies capture

in experience. No art can capture

simultaneously nature plus the humanmade plus the human being plus the

original place.

Ruin art is an ultimate in art. Its time

creates the ruin. Eventually, when the

human-made can no longer hold nature

at bay, nature takes over, but not until

then. When nature does take over,

cosmological time takes over. The insistent

move towards the not being of a ruin has

come to a stop. The ruin, however, will

always exist as having been.

6.

7.

8.

9.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Rose Macauley, Pleasure of Ruins (New

2.

York:Walkerand Co., 1953),p. 453.

Alois Riegl, Le culte moderne des

monuments. Son essence et sa genese,

DanielWieczorek,trans.(Paris:Editions

du Seuil, 1984),p. 119.

3. NathanielHawthorne,TheMarbleFaun

(Boston:Ticknor& Fields,1860).

4. On 17 November 1986 I presenteda

lecture entitled "Exploring Ruins as

Worksof Art" at the ExplorersClubin

New York.

5. See FlorenceM. Hetzler,"RuinsAs a

New Category of Being", Journal of

Aesthetic Education (Summer 1982) pp.

105-108;and "Estetikarusevina:Jedna

nova kategorija bica", knjisevna kritika

Leonardo

Subject

10.

(University of Belgrade) (Jan.-Feb. 1980)

pp. 87-95.

See "Den Reiz der Ruinen retten",

Salzburger Nachrichtung (25 July 1985),

p. 7. See also Paul Zucker, Fascination of

Decay (Ridgewood, NJ: The Gregg Press,

1968), p. 3; and Andrew Malcolm,

"Under Arctic Ice, a 19th-Century Ship

Tantalizes", The New York Times (17

March 1982).

See Eleanor Munro, "Art in the Desert",

The New York Times (7 Dec. 1986), p. 9.

See Walter Kaufmann, TimeAs an Artist

(New York: Readers Digest Press, 1978),

pp. 33-34; and Henry Kamm, "Rescuing

Ancient Glories from Modern Ravages",

TheNew YorkTimes(4 Dec. 1986), p. A4.

See Henriette Antonia (Groenewegen)

Frankfort, Arrest and Movement: An

Essay in Space and Time in the Representational Art of the Ancient Near East

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1951).

On 28 February 1986, at the Explorers

Club, his son, Alfred Bingham, showed

slides of the city as it was when his father

found it.

11. Georg Simmel, "The Ruin", in Kurt

Wolff, ed., Georg Simmel, 1858-1918

(Columbus,OH: Ohio State University

Press,1959),p. 259.

12. See George Kubler, The Shape of Time

(New Haven: Yale University Press,

1962); Paul MacKendrick,The Dacian

StonesSpeak(ChapelHill:Universityof

NorthCarolinaPress,1975),pp. 55-105;

Dragoslav Srejovic, Europe'sFirst Monumental Sculpture: Lepenski Vir (New

York: Stein & Day, 1972); Francis

20-Year

and

Author

Sparshott, "Antiquity of Antiquity",

Journal of Aesthetic Education 19, No. 1,

92 (Spring1985);and DavidLowenthal,

ThePast Is a ForeignCountry(Cambridge:

CambridgeUniversityPress, 1985),pp.

138-182.

13. See Linda Patrik, The Aesthetic Significance of Ruination (Ph.D. diss., 1978),

pp. 64-112; Robert Ginsberg, "Aesthetics

of Ruins", Bucknell Review 18, No. 3,

89-103 (Winter 1970); Roland Mortier,

La PoetiquedesRuinesen France(Geneva:

Librairie Droz, 1974); Mary Carman

Rose, "Nature As Aesthetic Object: An

Essay in Meta-Aesthetics" (paper deliveredat the BritishSociety of Aesthetics,

September 1975); Georg Simmel, "Reflexions sugg6erespar l'aspectdes ruines",

in Melanges de philosophie relativiste.

Contributiona la culturephilosophique,A.

Guillain, trans. (Paris, 1912),pp. 117-125.

14. See Mario Salvadori, "A Meditation on

Ruins" (University Lecture, Columbia

University, 29 January 1979); M.

Chasseboeuf Volney, Les Ruines ou

Meditationssurles Revolutionsdes Empires

(1972) and Volney's Ruins, Burton

Feldman and Robert D. Richardson,

trans. (New York: Garland, 1979);

Philippe Minguet, "IIgusto delle rovine",

rivista di estetica 21, No. 8, 3-8 (1981);

Frederick Golden, "Monumental Effort

in Java", Time (28 February 1983), p. 76;

Florence M. Hetzler, "Art is More than

Philosophy", Proceedingsof International

Congress of Philosophy (Taipei: Fu Jen

University Press, 1979), pp. 197-210; and

Der Fles, Elogio della disarmonia(Milan:

Garzanti, 1986), pp. 117-134.

Cumulative

Indexes

Leonardo announces publication in 1988 of complete subject and author indexes for

Volumes 1 through 20 of the journal. The cumulative 20-year indexes will be a significant

reference and teaching tool for artists, teachers, librarians, historians and researchers in

interdisciplinary fields.

The cumulative indexes will be published separately from the regular journal issues.

Further information on availability of the indexes and price (including back issue prices)

will be issued shortly to all subscribers.

Hetzler, Ruin Time and Ruins

55

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Apo CSM Line BreakerDocumento1 páginaApo CSM Line BreakerBruno De BorAinda não há avaliações

- What Is A Complex System?Documento35 páginasWhat Is A Complex System?falsedeityAinda não há avaliações

- Beautiful ChaosDocumento232 páginasBeautiful ChaosSina Keyhanian100% (2)

- Lovecraft, Cyclonopedia and Materialist Horror: I. Lovecraft Will Tear Us ApartDocumento4 páginasLovecraft, Cyclonopedia and Materialist Horror: I. Lovecraft Will Tear Us ApartBruno De BorAinda não há avaliações

- Joannesbaptistav00redg BWDocumento98 páginasJoannesbaptistav00redg BWBruno De BorAinda não há avaliações

- 9780415492126Documento33 páginas9780415492126Bruno De BorAinda não há avaliações

- Physis - Van HelmontDocumento28 páginasPhysis - Van HelmontBruno De BorAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Quantum PauseDocumento5 páginasQuantum Pausesoulsearch67641100% (2)

- MCQ Class VDocumento9 páginasMCQ Class VSneh MahajanAinda não há avaliações

- Fin - e - 178 - 2022-Covid AusterityDocumento8 páginasFin - e - 178 - 2022-Covid AusterityMARUTHUPANDIAinda não há avaliações

- Mca Lawsuit Details English From 2007 To Feb 2021Documento2 páginasMca Lawsuit Details English From 2007 To Feb 2021api-463871923Ainda não há avaliações

- Vodafone Idea MergerDocumento20 páginasVodafone Idea MergerCyvita Veigas100% (1)

- Aldehydes and Ketones LectureDocumento21 páginasAldehydes and Ketones LectureEvelyn MushangweAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Process Guide: St. Anthony's College Nursing DepartmentDocumento10 páginasNursing Process Guide: St. Anthony's College Nursing DepartmentAngie MandeoyaAinda não há avaliações

- HTTP WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee Haa Overseasdoctors Subs Sub133Documento3 páginasHTTP WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee Haa Overseasdoctors Subs Sub133hadia duraniAinda não há avaliações

- Some FactsDocumento36 páginasSome Factsapi-281629019Ainda não há avaliações

- StratificationDocumento91 páginasStratificationAshish NairAinda não há avaliações

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocumento3 páginasNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentVince Vince100% (1)

- FINAL Parent Handbook AitchisonDocumento68 páginasFINAL Parent Handbook AitchisonSaeed AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- TLE10 - Q3 - Lesson 5Documento17 páginasTLE10 - Q3 - Lesson 5Ella Cagadas PuzonAinda não há avaliações

- Wp406 DSP Design ProductivityDocumento14 páginasWp406 DSP Design ProductivityStar LiAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Miranda Catacutan Vs PeopleDocumento4 páginas5 Miranda Catacutan Vs PeopleMetoi AlcruzeAinda não há avaliações

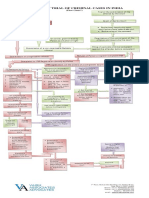

- Process of Trial of Criminal Cases in India (Flow Chart)Documento1 páginaProcess of Trial of Criminal Cases in India (Flow Chart)Arun Hiro100% (1)

- 2016 ILA Berlin Air Show June 1 - 4Documento11 páginas2016 ILA Berlin Air Show June 1 - 4sean JacobsAinda não há avaliações

- Rock Classification Gizmo WorksheetDocumento4 páginasRock Classification Gizmo WorksheetDiamond실비Ainda não há avaliações

- Surimi Technology: Submitted To: Dr.A.K.Singh (Sr. Scientist) Submitted By: Rahul Kumar (M.Tech, DT, 1 Year)Documento13 páginasSurimi Technology: Submitted To: Dr.A.K.Singh (Sr. Scientist) Submitted By: Rahul Kumar (M.Tech, DT, 1 Year)rahuldtc100% (2)

- APEX Forms Sergei MartensDocumento17 páginasAPEX Forms Sergei MartensIPlayingGames 301Ainda não há avaliações

- Guide Item Dota 2Documento11 páginasGuide Item Dota 2YogaWijayaAinda não há avaliações

- Closing Ceremony PresentationDocumento79 páginasClosing Ceremony Presentationapi-335718710Ainda não há avaliações

- OD2e L4 Reading Comprehension AKDocumento5 páginasOD2e L4 Reading Comprehension AKNadeen NabilAinda não há avaliações

- SHARE SEA Outlook Book 2518 r120719 2Documento218 páginasSHARE SEA Outlook Book 2518 r120719 2Raafi SeiffAinda não há avaliações

- FAR MpsDocumento2 páginasFAR MpsJENNIFER YBAÑEZAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Nicanor S. Bautista Agaton D. Yaranon Bince, Sevilleja, Agsalud & AssociatesDocumento9 páginasPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Nicanor S. Bautista Agaton D. Yaranon Bince, Sevilleja, Agsalud & AssociatesBianca BAinda não há avaliações

- Influence of Brand Experience On CustomerDocumento16 páginasInfluence of Brand Experience On Customerarif adrianAinda não há avaliações

- Slide Marine Cadastre 2Documento15 páginasSlide Marine Cadastre 2ajib KanekiAinda não há avaliações

- Housing Vocabulary TermsDocumento3 páginasHousing Vocabulary TermslucasAinda não há avaliações

- ShowBoats International (May 2016)Documento186 páginasShowBoats International (May 2016)LelosPinelos123100% (1)