Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

BOOK REVIEWS The Moral Economy of The Peasant

Enviado por

SociologíaEtcTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

BOOK REVIEWS The Moral Economy of The Peasant

Enviado por

SociologíaEtcDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

BOOI

REVIEWS

The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion andSubsistence in Southeast

Asia. By James C. Scott, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976, pp. 246,

$15.00

Recent studies of agricultural development have re-emphasized the importance of peasant behavior in determining agricultural policy. These studies

come at a time when the focus of development policy is moving from industrialization to the achievement of agricultural independence. Dr. Scott's

new study is a further contribution towards better understanding the peasant's

role in development by linking the peasant's economic behavior to his political

morality.

Scott believes that the study of peasant politics should center on what he

considers the critical problem of the peasant family: obtaining "secure subsistence." Starting from the traditional analysis of the farmer as a risk-averter,

he links the economic behavior of the peasant to his social environment

through the concept of the subsistence ethic. The subsistence ethic was a

combination of technical (e.g. planting techniques and seed varieties) and social

arrangements (e.g. patterns of reciprocity and work sharing) which had evolved

to reduce fear of food shortages. The subsistence ethic was the peasant's claim

to life.

Prior to the introduction of a modern market economy, the social

arrangements between the peasant and his village, the peasant and his landlord, and the landlord and the feudal state guaranteed that no one part of the

social web would demand so much from another that basic subsistence needs

would be threatened. These social arrangements were further enhanced by

traditional methods of crop growing which minimized risk and guaranteed, at

the margin, adequate annual production.

There is of course nothing unique in Scott's analysis of the peasant as a riskaverter-this is economically rational behavior and the focus of much work on

subsistence agriculture. What is unique is his coupling of the economic concept

of risk aversion to a moral framework of society. From this, two main implications may be drawn: First, peasant rebellions result from a dislocation of

THE FLETCHER FORUM

VOLUME 2

the peasant's "moral economy," that is "their notion of economic

justice and their working definition of exploitation;" secondly, the evaluation

of land tenure systems and their impact on peasants must first start from the

premise that subsistence-oriented peasants prefer to avoid economic disaster

rather than take risks to maximize their average income. The question is

whether a proposed land tenure system will guarantee a peasant his daily

sustenance.

Through two case studies, the Nghe-An and Ha-Tinh Soviets in northern

Annam and the Saya San Rebellion in Lower Burma in the 1930's, Scott first

develops his concept of a subsistence ethic and then discusses its transformation

under the impact of colonialism, concluding with an examination of the causes

of peasant revolt.

To determine if subsistence security is the most active principle governing

peasant behavior, Scott examines various aspects of village life, e.g. social

stratification, village reciprocity, tenancy, and taxation. One of Scott's more

interesting contributions is his analysis of class stratification in peasant society.

Security against crisis determines stratification; not the highest income but

rather the highest security against disaster determines status. Thus the small

landowner ranks higher on the ladder of respect than the tenant farmer, despite

the fact that the tenant may earn more.

One implication of this for social conflict in peasant society is that the

peasant will exhibit the greatest resistance to downward mobility at that point

where -the threshold between security-insecurity is reached. A second implication is that control of land becomes the basis of power. The landowner not

the peasant was required to take positive action to maintain security by

reducing his rent demands or by providing generous credit in times of low

productivity.

Thus, the failure to take care of one's dependents, not economic inequality,

was the basis for peasant unrest. There is a standard by which elites can be

judged and by which the legitimacy of their claims on peasant resources can be

determined. Exploitation is measured from the point of view of the exploited;

what matters is not inequality or poverty but that claim which threatens the

central element of the peasant's subsistence arrangements. Insecure poverty,

rather than poverty alone, nurtures revolt. Peasants revolt as consumers not as

producers which, in part, explains the essential conservative nature of most

peasant rebellions, seeking to recreate a secure past.

The introduction of colonial systems, the commercialization of agriculture,

and rapid population growth instigated a period of radical change in rural

society, leading to new patterns of insecurity and exploitation. Several major

effects of these dislocating changes are identified: exposure of the peasant to

market insecurities; erosion of village kinship groups and risk-sharing

obligations; reduction or elimination of subsidiary occupations producing

NUMBER I

BOOK REVIEWS

additional income for the peasant farmer; collection of rent as a fixed charge,

developing an impersonal and contractual relationship between the tenant and

landowner; and the introduction of a system of national tax-collection

unresponsive to the vagaries of life facing the peasant household.

From a diffuse, mutually supportive relationship, the status between landowner and tenant developed into an impersonal, contractual relationship.

The power of the landowner over his tenant increased correspondingly while

the reciprocal obligations of the owner to the tenant weakened.

Much of the impetus for these changes is seen by Scott not as evolutionary but

as a series of "rude shocks" caused by fluctuations in the world market, the

major shock being the 1930s Depression. Scott notes that a large scale rupture

of interclass bonds is conceivable only in a market economy, the traditional

societies' social bonds being more permanent and less economic. The integration of the peasant economy into the world economy made possible a

large-scale failure of social guarantees.

Scott challenges the notion that hungry people are too weak to rebel or that

unrest is due to frustration of rising expectations and relative deprivation.

Instead, peasants revolt to protect threatened sources of subsistence. Therefore,

exploitation is a necessary but not a sufficient cause for rebellion. What is

needed is a threat to the peasant's perception of his subsistence level. In this

situation, the peasant is a political actor standing in judgement of his society's

moral structure. Scott argues against the "mystification" of these revolts;

peasants do not, he notes, require outsiders to tell them they are being exploited.

In his conclusion Scott draws some implications for current policy in

Southeast Asia. In particular he addresses the possible effects of agrarian

development via the "Green Revolution" (the development of high yield

varieties of rice and improved farming methods). He concludes that the

agrarian revolution is apt to displace labor and concentrate land ownership

further in the hands of a few.

Migration from the agrarian sector to the urban will weaken traditional village

ties and norms and drain young leadership from the village. Scott interprets the

widespread use of patronage in the cities as a stop-gap measure to manage

grievances, doomed to failure without the necessary structural changes. The

burden of patronage is apt to grow faster than the scarce resources required to

service the new obligations of the elite.

Scott's study places the peasant at the center of political and economic

change. While he draws the majority of his conclusions from historical case

studies, their implications are obvious for current policies and tensions in

developing countries. For instance, does a subsistence ethic exist over food in

India or over petrol price increases in the Phillippines? By reminding us that

development contains a normative element which can only be properly

THE FLETCHER FORUM

VOLUME 2

evaluated from the vantage point of the individual upon which social change

has its greatest impact, Dr. Scott has challenged us all.

RICHARDJ. KESSLER

RichardJ. Kessler is a candidate for the Ph.D. at The Fletcher School.

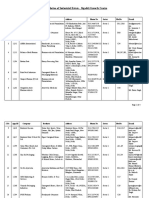

NationalSecurity Memorandum 39: The KissingerStudy ofSouthern Africa.

Edited and introduced by M.A. El-Khawas and B. Cohen. Westport, Conn.:

Lawrence Hill & Co., 1976, pp. 189, $3.95 (paper), $6.95 (cloth).

A National Security Council Interdepartmental Group for Africa, consisting

among others, of the CIA, AID, and the Departments of Defense and State,

was set up in 1969 in response to National Security Memorandum No. 39

issued by Kissinger. The memo demanded a comprehensive study outlining

various policy choices open to the United States with respect to the then

Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique, and to the racist regimes of

South Africa, Rhodesia, and occupied Namibia. The bold conclusions of the

study-classified as secret but leaked to newspapers in Britain and the

US-included definitive statements that:

. . [US] interests in the region are important but not vital ... The US

does not have vital security interests in the region ... None of the interests are vital to our security, but they have political and material

importance...

In spite of these informed opinions, the study reproduced in this book is

disturbing to read as it ignores any discussion of the human element in these

areas; this alone ought to form the basis of judging what price the US pays,

when it chooses to actively strengthen the governments in this region. Even the

editors have not seen this fundamental weakness of the study.

The study offers the US options ranging from disassociation with the white

racist regimes to complete disassociation with the rest of Africa in support of

the former. In between are choices - often contradictory - such as that which

attempts to maintain relations with the rest of Africa as well as with the racist

regimes in the South.

EI-Khawas and Cohen, in a short but substantial work, have provided a

survey of the trend in US policy between 1969 and 1976 which shows that

NUMBER I

BOOK REVIEWS

"Option Two" - the contradictory option - was the one chosen by Kissinger

for the US. In fact, these authors demonstrate how the US Government in

pursuit of "Option Two" spent money to buy support elsewhere in Africa so

that the State Department could voice disapproval of apartheid; meanwhile,

the Defense Department and the business and military industrial complex

expanded their roles in South Africa. Even NATO was, and is still being used

to strengthen South Africa.

Kissinger's choice was based on what the two editors correctly identify as a

false belief that liberation movements are incapable of success. Mozambique

and Angola enlightened Kissinger, and the 1976 US proposal for a compromise

solution to Rhodesia resulted. The book does not deal with recent developments such as the emergence of the Frontline States which are unlikely to be

bought off with dollars. The Democratic Administration is nearly one year old,

but there has been no noticeable departure from the Kissinger design. Andrew

Young has not yet realized what the option means to the African leaders

genuinely interested in liberation. Perhaps the material commitments of the

US that were encouraged by the past administration are too intricate to untangle without serious vibrations in domestic politics.

As a result, the US is likely to continue its support for the military-industrial

infrastructure of Africa, especially since laws governing foreign military sales

were amended in 1974 to favour "commercial" rather than state training of

foreign military personnel or production of military goods.

The book is a brief but stimulating exposure for those interested in the study

of decision making in a complex government, especially in the area of foreign

policy, and also for those with expressed pretentions of support for human

rights. Southern Africa is not yet solved - more reason why the book is useful

as providing a focus within which to try to influence the behavior of the US.

SHADRACK

B. 0. GuTro

Shadrack B. 0. Gutto, LL.B. (hons) ison leave from the Institute for Development Studies at the

University of Nairobi. He is working toward a Ph.D. at The Fletcher School.

International Security Studies Program

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

Tufts University

Medford, Massachusetts 02155

The Program in International Security Studies provides

multidisciplinary instruction in a wide range of subjects covering

the general topics of international peace and security. It centers on

the role and limitation of force in international relations.

In addition to the courses of instruction, the Program offers

individual and collective research and publication opportunities. A

series of books containing material presented in its colloquia and

annual conferences has been published under its auspices.

NOW

AVAILABLE

The Lessons of Vietnam, edited by W. Scott Thompson and

Donaldson D. Fizzell, (1976) Published by Crane Russak

and Company, Inc.

The Other Arms Race, edited by Geoffrey Kemp, Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Uri Ra'anan, (1975) Published by Lexington

Books, D.C. Heath and Company

The Superpowers in a Multinuclear World, edited by Geoffrey

Kemp, Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Uri Ra'anan, (1974)

Published by Lexington Books, D.C. Heath and Company

European Security and the Nixon Doctrine, report of ISSP Conference 1972. International Security series, number 1.

(1973). Published by Tufts University.

FORTHCOMING

The Military Buildup in Non-Industrial States, edited by Uri

Ra'anan, Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., Geoffrey Kemp, (1978)

Published by Westview Press

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Plants For Food and Fibre WebquestDocumento2 páginasPlants For Food and Fibre Webquestapi-237961942100% (1)

- Writing - Sentence & Note ExpansionDocumento14 páginasWriting - Sentence & Note ExpansionEmmot LizawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Potential Analysis For Further Nature Conservation in AzerbaijanDocumento162 páginasPotential Analysis For Further Nature Conservation in AzerbaijanGeozon Science MediaAinda não há avaliações

- CASSAVA CHIPS BISNIS RevisiDocumento19 páginasCASSAVA CHIPS BISNIS RevisiTayaAinda não há avaliações

- Nut R 405 Project 3 PaperDocumento25 páginasNut R 405 Project 3 PaperAna P.Ainda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento20 páginasIndus Valley CivilizationRAHUL16398Ainda não há avaliações

- Endosulfan TragedyDocumento16 páginasEndosulfan TragedyAbhiroop SenAinda não há avaliações

- Ecologically Based Rodent ManagementDocumento486 páginasEcologically Based Rodent ManagementAnju Lis KurianAinda não há avaliações

- Devhuti H LakheyDocumento43 páginasDevhuti H LakheyAbhinav AshishAinda não há avaliações

- ANSI A300 Part 8 - Root Management (2013)Documento24 páginasANSI A300 Part 8 - Root Management (2013)Logan0% (1)

- The Power of Argentine BeefDocumento3 páginasThe Power of Argentine BeefPinasti natasyaAinda não há avaliações

- Archicentre Cost GuideDocumento5 páginasArchicentre Cost GuideAli Khan100% (1)

- SIP Brochure 2015 17 Final LRDocumento48 páginasSIP Brochure 2015 17 Final LRanushiv rajputAinda não há avaliações

- Galene Irrigation System ProjectDocumento108 páginasGalene Irrigation System Projectburqa100% (3)

- Schmandt-Besserat - The Earliest Precursor of WritingDocumento17 páginasSchmandt-Besserat - The Earliest Precursor of WritingIvan Mussa100% (1)

- Multiple Choice Questions Organized by Freller Chapter 11 The Industrial Society and The Struggle For Reform 1815-1850Documento40 páginasMultiple Choice Questions Organized by Freller Chapter 11 The Industrial Society and The Struggle For Reform 1815-1850ashmitashrivasAinda não há avaliações

- Halimaw MachineDocumento21 páginasHalimaw MachineJoana Doray100% (1)

- Final Project Ssed 122Documento4 páginasFinal Project Ssed 122Jesille May Hidalgo BañezAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Pest Management in WatermelonDocumento42 páginasIntegrated Pest Management in WatermelonGuruPrasadAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affectingaquaculture Productioninuganda, Gulu DistrictDocumento52 páginasFactors Affectingaquaculture Productioninuganda, Gulu DistrictOLOYA LAWRENCE KABILAAinda não há avaliações

- FernDocumento36 páginasFernMarija MarkovićAinda não há avaliações

- AKSESOUAR - KOTΣΑΔΟΥΡΕΣDocumento11 páginasAKSESOUAR - KOTΣΑΔΟΥΡΕΣinfo7879Ainda não há avaliações

- Directory Sugar Refineries 2021 2022Documento2 páginasDirectory Sugar Refineries 2021 2022J Paul VarelaAinda não há avaliações

- Asuka A200 Manual EnglishDocumento19 páginasAsuka A200 Manual Englishjack2551Ainda não há avaliações

- LOA SiggadiGrowthCenterKotdwar1442650109Documento4 páginasLOA SiggadiGrowthCenterKotdwar1442650109UDGGAMAinda não há avaliações

- Bois de Rose & DémocratieDocumento60 páginasBois de Rose & DémocratieNyaina RandrasanaAinda não há avaliações

- Training Manual On PCR Detection of Enterocytozoon Hepatopanaei 17-18 August 017Documento52 páginasTraining Manual On PCR Detection of Enterocytozoon Hepatopanaei 17-18 August 017Anonymous VSIrcb4I100% (1)

- Fish Farming IELTS Listening Answers With Audio, Transcript, and ExplanationDocumento6 páginasFish Farming IELTS Listening Answers With Audio, Transcript, and ExplanationQuocbinhAinda não há avaliações

- About Punjab - Draft - Industrial - Policy - 2017 - July - 28 PDFDocumento96 páginasAbout Punjab - Draft - Industrial - Policy - 2017 - July - 28 PDFInterads ChandigarhAinda não há avaliações