Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Interactive Spacefrane

Enviado por

Andrei GrigoreDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Interactive Spacefrane

Enviado por

Andrei GrigoreDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1

Design and Boundaries:

Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of

Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

John Frane, Predock_Frane Architects

Hadrian Predock, Predock_Frane Architects

The problem of designing family-oriented museum space is ripe with opportunities stemming

from the complex matrix of relationships between the collections, curators, educational

objectives, and spatial parameters. These same relationships are rife with complexities and

potentially competing agendas. Our brief will focus on the edges that exist where these

ideologies meet, both in terms of the dynamic design process and as it relates to the resultant

architectural space of the Getty Family Room. We are fascinated with how these slippages and

inherently unpredictable forces have the ability to reshape interactive environments in a positive,

and sometimes negative way.

The new Getty Family Room project is simple in concept a space that introduces families to art

concepts and activities. As a built work it is also quite easy to engage and occupy. However, this

simplified experiential understanding veils the complex and dynamic relationships that underpin

the project. The accumulated evolutionary design process of testing, learning, discarding, and

saving is hidden from sight, but this invisibility is in a way a project also one that deserves to

be exhibited, revealed, and critiqued. In the case of the Getty Family Room, this involved an

expanded field of client, consultants, specialists, and a series of nuanced negotiations across the

various disciplinary boundaries. In addition, boundaries between institution and project, new and

existing, and young and old become important areas to re-visit. These boundaries deserve a

special focus because the way that these edges are defined, approached, engaged, or ignored

can mean radically different results for each project. From the architects perspective, this

becomes critical to formulating a process, a project, and ultimately a practice. From the larger

design teams perspective, how this happens can mean success or failure for the project.

For a diminutive space of 800 square feet, there was an expansive design team formulated under

the direction of the Getty for the design of the Family Room. The following list represents the

impressive and large core conceptual design team: administrators, curators, facilities

managers, exhibition designers, child development specialists, education specialists, art

educators, museum directors, museum consultants, architects, facilities managers, and

specialized engineers.

Within this matrix, like a physics experiment, there exists the potential for a myriad of both

negative and positive forces to be exerted and ultimately shape the project. Among the more

infamous project killers are: turf wars, design by committee, information overload, too many

cooks, righteousness, aesthetes, egos, snobbery, and purists. All of these appear to be at odds

with an idealized process one that begins with strong informational and conceptual

underpinnings, a rigorous and well managed cooperative development of these ideas into

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

compelling spatial, educational, and experiential realities ultimately expressed in a clear and

compelling project where success can be tangibly measured at many levels.

With so many parties involved, so many different boundaries, how can a project ever achieve

this elusive goal? Should most of the trust and responsibility be placed in the hands of the

architect? Are all of these bodies really contributing to a better project? Is all of that information

really necessary or even possible to synthesize? Is this the best way to organize a project? At a

certain point doesnt the ratio of square footage to number of parties around a conference table

become absurd?

These become important questions with regards to the structure of the design process and in

particular to the way in which boundaries are defined. To test this theory we will first look at a

few comparative models of the design process with the architect positioned in different ways,

and then re-focus on the actual Family Room project to explore some specific relationships and

their effects.

Lets start with the so-called empowered architect scenario. (This scenario could also be called

the heroic model or the Howard Roark model from the architect in Ayn Rands Novel The

Fountainhead):

In this scenario the architect is handed an initial brief that details parameters of the project. He

can then return to his studio, read some books, study the latest child developmental issues, and

brush up on his exhibition design. He can speak with his children and come back with a brilliant

design. There is no need to keep crossing boundaries; in fact many specialists can be eliminated

from the project team altogether saving money and time. This model has its distinct advantages.

In it boundaries are sacred and not to be crossed. They allow for a productive autonomy. The

boundary is just that a boundary, protective and shielding. The parties understand their roles

and respect one another (or at least pretend to). The architect can completely control the

situation. The architect can design the one true scheme not options, not watered down

variations. There are no meddlers, no closet designers, no committees, and no political

correctness. The architect can claim full authorship for a directors cut design.

But wait. Is this so smart for the architect; is this so smart for design in general? Is this an old

and outmoded model? What about all those amazing and potentially new ideas that were never

aired or considered? And how about those critical areas of input that the architect failed to

consider? And who will take responsibility for a project high on aesthetics and low on content.

The client?

Modernism may have shattered previous models of architecture, but it largely perpetuated the

heroic role of the singular (often white and male) architect, and often white and often contentless architecture. Does this model not still linger in the air of museums? And what does

singularity and heroic vision ultimately yield? Further, what place does a rarified heroism have

in the presence of children who will just destroy it?

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

Lets explore another scenario as an alternate: lets call this one the submissive architect

scenario:

This architect or architectural group aims to please everyone. Like a puppy that desperately

wants love and shies away from difficult and confrontational situations, this architect will

quickly and expeditiously enable design by committee. This architect opens up the boundary

floodgates and takes expeditious notes of oversimplified translations. Like an allergic reaction,

formerly closed cell membranes become instantly permeable, allowing the most contamination

possible between disciplines. This architect will single-handedly reduce the infinite number of

exciting design potentials to one heaping loveable politically correct pile of building, and will

tend to treat children as some kind of limited destructive organism that only responds to large

primary-colored geometric shapes, or computer screens with mindless rudimentary games. But

hey, thats what the public wants right? Wrong. Its what theyve been conditioned to expect.

But wait again theres hope. Lets take a look at one other version.

Lets call this version the projective practice because it sounds cool and is very topical right

now:

First off the architect is no longer singular in any way and no longer heroic and no longer

really an architect proper. This new approach and practice is all about hybridity, collaboration,

cross boundary dressing, intelligence eavesdropping, and the erosion of authorship. More

Buddhist, less Catholic. The architect as content and information steward. A new flesh adaptable

negotiator design body. You want it you got it.

This open model is all about digging into the space of the boundary and exploiting its edges.

The projective practice sees that where two things meet, a new third space is created, a hybrid

space that is fertile with possibility: Where curation meets architecture bang!, where childhood

developmental issues meet material explorations bang!, where art concepts meet spatial

containers bang!. The meeting of edges in this sense becomes a kind of conceptual detonation

point, a performative zone to capitalize upon. In this scenario ideas and information are thought

of on equal footing. It doesnt matter where or who initiates a good idea, or valuable information.

What matters is how it is handled, cared for, nurtured and deployed. This form of reciprocity

across boundaries is akin to passing a marshmallow across a fire. A perfectly golden crust with a

soft and melted interior requires an exacting negotiation between the two sides.

For this model to work in a maximal way, the traditional models of heroism and submission must

be fully suppressed. The architect must be willing to fully engage the various parties that have

come to the table to move into their territory, immerse themselves in their lingo and subcultures, and they must be honest about their ignorance and navet. The architect must be

willing to consider ideas that at first seem foreign, trite, and irrelevant. The architect must be

willing to subject their process to open scrutiny, and at times uncomfortable situations. Most

importantly, they must also be willing to challenge and provoke the committee and consultants,

not to accept clichs, and not to be fearful of tension. For this kind of process to be fully

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

exploited, it requires a generous reading on the part of the architect and an enormous willingness

to test the teams postulations.

Within this model, the architect becomes the master interpreter instead of the just plain Master or

the mis-interpreter. In order for this role to properly function, the various other parties on the

design team must recognize two important pieces of information. First, they must recognize that

they are active contributors to a dynamic design process, and that their thoughts, knowledge, and

information is critical to establishing a robust conceptual base for the project and a reciprocal

dialogue between specialized areas and a general solution. Secondly, they must acknowledge that

the architectural team must ultimately coordinate, interpret, and most importantly test spatial

manifestations. Therefore the design team must be willing to see their thoughts pass through a

sieve of translation and remain open to the resulting experimentation. They must understand that

this is an iterative model with constant editing and re-consideration. And the larger design team

must remain open to the fact that the architect is the expert in their discipline.

This type of process is inherently based on tension. Tension actually defines and makes visible

the new space where boundaries meet. Tension in this model is embraced and exploited.

So, we are obviously promoting this kind of model, and to a degree idealizing it, but clearly there

are risks associated with it. For example, if the architect does not exert the right balance of

control and submission, the scales could easily tip in either direction. The issue of border

crossing and hybridity also becomes tricky. To navely cross over any boundary one risks the

possibility of being tainted, co-opted, or even corrupted. And to forcefully hybridize, one could

accidentally create a monstrous mix instead of a handsome new version. These are very similar

boundary issues as one finds in biotechnology, only less dangerous. Open scrutiny also comes at

a cost. This generally implies a much more laborious and intensive process for the architect,

where the demonstration of ideas is iterative and slowly defined. And if the architect loses

control of this process, the design will suffer greatly. Furthermore, the architect needs to become

more objective about the design and be willing to suspend personal feelings. Provoking the client

implies that the client is willing to be provoked, which isnt always the case. To expect the great

variety of specialists to come to the table with equally open perspectives and a willingness to

engage the space of the boundary is a bit absurd. So, the architect and key leaders from the client

group must attempt to energize this atmosphere from the start. All of this puts a tremendous

amount of pressure and responsibility on the architect to perform a surgical translation and

assimilation. On the other hand, it also spreads out the liability and credit across the group.

Lets re-visit the Getty Family Room, not as a case study per se, but again as a specific example

to focus a larger discourse upon.

We would like to first show a quick overview of the project with a synopsis of the key

components and the main conceptual ideas.

Like a budding flower with extended roots, the new Family Room stitches the informal/local

activity of experiencing art through intuitive play to the larger experience of the Gettys

collections.

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

The design of the project is based on a series of oppositions that react in a complimentary way to

Meiers design for the campus. While the Getty may be thought of as an extensive, permanent,

monochromatic, and formally based project, the Family Room is conceived as a diminutive,

temporary, polychromatic, experientially based room within a room.

The project is made up of two concentric components: the first consists of six coves within the

existing white box gallery. Each cove relates to one of the six areas of the Gettys collections:

Drawing, Illuminated Manuscripts, Photography, Painting, Sculpture, and French Decorative

Arts. Nestled together like a Rubiks cube, and scaled to human height within a 20-foot cubic

gallery, each cove contains a focused activity that relates to a specific work of art. Against the

backdrop of these pieces, a spectrum of educational objectives and art/developmental issues are

addressed via intuitive and experientially based engagement, and using both fine and gross motor

skills. There is little text in the entire project. Each cove is lined in an intense color that is

amplified or contrasted in a complimentary way to color sampled from the representative

artworks. The exterior surface of these mini-spaces is a reflective, continuous skin, occasionally

interrupted by views inside the coves, through lenses, or child-scaled cutouts.

While the coves are focused and isolated, perimeter treasure hunt walls intermittently

punctuate the outer wall of the gallery. Following tongues of color from the coves, these

fragmentary walls are embedded with objects and detailed images that one views through a series

of peepholes. The images and objects within relate to the broader collection in the galleries and

create a link between childhood/family fun and the lifelong experience of enjoying art. The

peepholes can be experienced casually, or in a more structured and challenging atmosphere,

where the venture might extend into the actual galleries.

Now, lets explore in a more specific way some of the boundary dynamics that relate to this

project.

The design of interactive space, and specifically, family-oriented museum space inherently

synthesizes architecture, interior design, exhibition, education, technology, art, and even

urbanism and landscape. This is an exciting and daunting list of ingredients that could ultimately

manifest itself as isolated ideas within the same space, or as a carefully orchestrated and

choreographed assembly where traditional boundaries are broken down and exciting new

possibilities emerge.

To start with the more general boundaries of new versus existing, the obvious polar

considerations are either establishing a respectful or assertive relationship. Should the new space

have an embracing identity with respect to the larger sphere? Is the new space an extension of

curatorial ideas that are already established? Can or should the museum be a subject of critique

at a number of different levels from content to philosophy to architecture? Is the new space a

freestanding independent exhibition? Is it seen as an instrumental link to a larger set of issues?

Our attitude as it relates to these issues, is that the new family room as a space should be neither

critical nor embracing, but rather performative and instrumental. In other words, instead of just

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

containing exhibition material and being an independent space within the larger campus or

establishing a strong stance toward the existing, it should try to perform at several different

levels, activating many different boundaries, be they conceptual, educational, spatial, material,

atmospheric, etc. And, like an instrument, it should bring something about and begin to register

these events, like an awareness of a larger set of issues, or a concrete connection to a specific

work of art, or the identification of something everyday like a bug.

We view these actions as very specific engagements with boundary conditions, where the edges

are pulled, twisted, tied together, and fused.

In a way it would have been easy to critique Meiers work and establish a kind of rebelliousness.

It would have been even easier yet to cloak our project within the white 30-inch grid, but a more

interesting approach for us is to conceptually sample from his work, exploring the space between

the existing body and the new. This allows it to be an active part of our design process where it

would be transformed into something very different.

Instead of announcing a critical agenda, or an accommodating agenda, I believe that we were all

interested in more of an enabling agenda.

How about the very real and very specific meeting of boundaries within the various disciplines

and architecture? Does exploiting and engaging these have measurable impact and affect? Lets

look at some examples both positive and negative.

Take facilities and architecture: its clear that facilities is a constant thorn in the side of the

architect, always presenting codes, barriers and rules that cant be broken. This is traditionally a

meeting of worlds where the defined boundary comes in handy, and the architect is typically

looking for red flags and only enough dialogue to understand the problems. But can something

that at first glance appears mundane actually be a boundary waiting to be properly engaged? Can

technical issues like cleaning, maintenance, and exiting actually be informative and

informational at a conceptual level? Instead of a barrier to full aesthetic realization, can they be

considered a way of helping the project to perform and be more fully realized?

Many of our material choices and consequently atmospheric effects for the Family Room were

motivated by discussions at this level. Flow, exiting, and movement issues had a major role in

determining the basic organization of the space. Further, long term consequences for the project

stem out of the dialogues that emerge from these boundaries. A commitment to a long term,

holistic view of maintenance has radically different consequences versus a reactive stance.

Or, lets look at the relationship between curatorship and architecture. The traditional

relationship, which maintains a stable boundary, looks at architectural space as containing

something that has been curated. But, if one begins to examine the meeting of these two areas at

a micro level, you will discover that there is a lot of common DNA. From the architects

perspective this seems like a tremendous opportunity to explore a hybrid of curatorship and

architecture. An open view of this idea from the curators perspective could mean new

translations; interpretations or understandings of artwork translated into an architectural

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

vocabulary. And in a complimentary way the architecture could affect curatorial methods or

decisions. However, there is a structure of value and authenticity that pervades the curators

world and creates an inherent difference in relation to architecture. This desire for authenticity

can be crippling to exhibition space when taken too literally, or unsuccessful when forcibly

hybridized with incompatible architectural space.

The boundaries that have traditionally divided educational intent and architectural space are well

known. Often in interactive environments there is barely a discernible interest between the two.

In fact the educational objectives often seem to be in direct opposition to the architectural ones.

From the architects perspective education typically equals a lot of text or computers. And from

the educators perspective architecture is often thought of as just a shell to support their

objectives. The space where these boundaries meet is in fact an incredibly potent space that has

barely begun to be exploited. During our early dialogues for the Family Room with education

specialists we established a series of objectives that attempted to stitch into the architecture a

spectrum of developmental issues, art concepts, activities and intelligences to be explored.

Examples of these are, gross and fine motor skills, teamwork, interactivity, abstraction,

perception, recognition, composition, distillation, and elaboration. This spectrum of ideas served

to establish the fundamental architectural concepts and the identity of the coves, reinforcing the

fusion of spatial design and the educational agenda. Furthermore, in contrast to those of the

traditional art galleries and other family based interactive spaces the teams intention was to

include minimal text and to have a goal of intuitive, approachable, and direct hands-on contact.

In conclusion, it is clear that there are successes and failures that stem from these explorations.

Just because we are now talking in the language of hybridity, overlap, and performance there is

no guarantee of success. In fact, there are many emerging architectural and interactive examples

that tend to take this terminology too literally, fail to understand the potential, or mismanage a

very complex series of steps.

However, future explorations of new boundary formulations and definitions have the real

potential to open up larger questions and conceptual issues that begin to be quite interesting at a

philosophical and political level. How can interactive spaces position themselves in new ways

within a discourse of authenticity and artifice? Can this, or should this line be further broken

down? Is the new space a facsimile of the original? Does it assert an identity beyond the

curatorial agenda of the institution or collections? Is the new space ghettoized or is it

intentionally inserted into the main gallery fabric? Is there a more radical engagement with the

actual art?

Questions like these, if followed, could lead to a more progressive re-thinking of family based

interactive space, and open up territory long understood as fixed. We are incredibly excited by

some of the outcomes in the Getty Family Room as a result of an assertive boundary

engagement, and are excited to see this level of exploration engender a more continual and

intelligent evolution.

Design and Boundaries: Exploring the Boundary Relations within the Context of Interactive Family-Oriented Museum Space

Presented at the J. Paul Getty Museum Symposium, From Content to Play: Family-Oriented Interactive Spaces in Art and

History Museums, June 4-5, 2005.

2005 Predock_Frane Architects

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- 0801871441Documento398 páginas0801871441xLeelahx50% (2)

- Module 8 - Emotional Intelligence Personal DevelopmentDocumento19 páginasModule 8 - Emotional Intelligence Personal DevelopmentRoxan Binarao-Bayot60% (5)

- Benson Ivor - The Zionist FactorDocumento234 páginasBenson Ivor - The Zionist Factorblago simeonov100% (1)

- Enter Absence APIDocumento45 páginasEnter Absence APIEngOsamaHelalAinda não há avaliações

- VDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentDocumento36 páginasVDA Volume Assessment of Quality Management Methods Guideline 1st Edition November 2017 Online-DocumentR JAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient To Roman EducationDocumento10 páginasAncient To Roman EducationAnonymous wwq9kKDY4100% (2)

- Design Process For Museum & ExhibitionDocumento15 páginasDesign Process For Museum & ExhibitionAmr Samy Lopez100% (2)

- Dadm Assesment #2: Akshat BansalDocumento24 páginasDadm Assesment #2: Akshat BansalAkshatAinda não há avaliações

- G. Lewis The History of MuseumsDocumento19 páginasG. Lewis The History of MuseumsManos Tsichlis100% (2)

- ShotcreteDocumento7 páginasShotcreteafuhcivAinda não há avaliações

- Harmonious Exchange Ecomuseums For Social HarmonyDocumento1 páginaHarmonious Exchange Ecomuseums For Social HarmonyAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Prirucnik Za Pisanje ProjekataDocumento114 páginasPrirucnik Za Pisanje ProjekataNevena КОНТРОЛ ФРИК BorojaAinda não há avaliações

- Curator Henne S DeweyDocumento13 páginasCurator Henne S DeweyAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Thinking About Starting A MuseumDocumento37 páginasThinking About Starting A Museumlyca809Ainda não há avaliações

- New New FuturesDocumento2 páginasNew New FuturesAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Unit3 SirefmanDocumento18 páginasUnit3 Sirefmanacozarev100% (1)

- PMMGuideDocumento23 páginasPMMGuideAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Aster Gdem2Documento11 páginasAster Gdem2nincsnickAinda não há avaliações

- EoDocumento63 páginasEoAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- 05 Tabele Exig Cer ConfortDocumento1 página05 Tabele Exig Cer ConfortAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- DK 2011 03 Art01Documento19 páginasDK 2011 03 Art01Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction Sustainability Lecture1Documento24 páginasIntroduction Sustainability Lecture1Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To International Building Codes Lecture ThreeDocumento24 páginasIntroduction To International Building Codes Lecture ThreeAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction Sustainability Lecture1Documento24 páginasIntroduction Sustainability Lecture1Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1Documento29 páginasLecture 1Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction Sustainability Lecture3Documento23 páginasIntroduction Sustainability Lecture3Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 2Documento26 páginasLecture 2Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- LDocumento6 páginasLAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- JPI Article Project ApproachDocumento4 páginasJPI Article Project ApproachAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- G: A New Approach For Safe & Sustainable Construction: The International Code Council (Icc)Documento2 páginasG: A New Approach For Safe & Sustainable Construction: The International Code Council (Icc)Andrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture Two: Planning - Programing - : ProceduresDocumento22 páginasLecture Two: Planning - Programing - : ProceduresAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Net Zero WalgreensDocumento3 páginasNet Zero WalgreensAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- 2 CaseStudies ExampleDocumento2 páginas2 CaseStudies ExampleAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Raynolds Re Lighting ArticleDocumento2 páginasRaynolds Re Lighting ArticleAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Dallas LEEDDocumento1 páginaDallas LEEDAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- Programing ToolDocumento2 páginasPrograming ToolAndrei GrigoreAinda não há avaliações

- LADP HPDocumento11 páginasLADP HPrupeshsoodAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation - DPP 01 (Of Lecture 03) - Lakshya NEET 2024Documento3 páginasPrinciples of Inheritance and Variation - DPP 01 (Of Lecture 03) - Lakshya NEET 2024sibasundardutta01Ainda não há avaliações

- Attitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationDocumento9 páginasAttitude of Tribal and Non Tribal Students Towards ModernizationAnonymous CwJeBCAXpAinda não há avaliações

- Adolescence Problems PPT 1Documento25 páginasAdolescence Problems PPT 1akhila appukuttanAinda não há avaliações

- Faculty of Engineering & TechnologyDocumento15 páginasFaculty of Engineering & TechnologyGangu VirinchiAinda não há avaliações

- The Eye WorksheetDocumento3 páginasThe Eye WorksheetCally ChewAinda não há avaliações

- Bethelhem Alemayehu LTE Data ServiceDocumento104 páginasBethelhem Alemayehu LTE Data Servicemola argawAinda não há avaliações

- E WiLES 2021 - BroucherDocumento1 páginaE WiLES 2021 - BroucherAshish HingnekarAinda não há avaliações

- Outbound Idocs Code Error Event Severity Sap MeaningDocumento2 páginasOutbound Idocs Code Error Event Severity Sap MeaningSummit YerawarAinda não há avaliações

- Electron LayoutDocumento14 páginasElectron LayoutSaswat MohantyAinda não há avaliações

- CV - Mohsin FormatDocumento2 páginasCV - Mohsin FormatMuhammad Junaid IqbalAinda não há avaliações

- Project - Dreambox Remote Video StreamingDocumento5 páginasProject - Dreambox Remote Video StreamingIonut CristianAinda não há avaliações

- Hssive-Xi-Chem-4. Chemical Bonding and Molecular Structure Q & ADocumento11 páginasHssive-Xi-Chem-4. Chemical Bonding and Molecular Structure Q & AArties MAinda não há avaliações

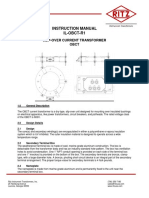

- Instruction Manual Il-Obct-R1: Slip-Over Current Transformer ObctDocumento2 páginasInstruction Manual Il-Obct-R1: Slip-Over Current Transformer Obctبوحميدة كمالAinda não há avaliações

- RL78 L1B UsermanualDocumento1.062 páginasRL78 L1B UsermanualHANUMANTHA RAO GORAKAAinda não há avaliações

- Cooperative LinuxDocumento39 páginasCooperative Linuxrajesh_124Ainda não há avaliações

- The Origin, Nature, and Challenges of Area Studies in The United StatesDocumento22 páginasThe Origin, Nature, and Challenges of Area Studies in The United StatesannsaralondeAinda não há avaliações

- BPI - I ExercisesDocumento241 páginasBPI - I Exercisesdivyajeevan89Ainda não há avaliações

- Section ADocumento7 páginasSection AZeeshan HaiderAinda não há avaliações

- P4 Science Topical Questions Term 1Documento36 páginasP4 Science Topical Questions Term 1Sean Liam0% (1)

- TextdocumentDocumento254 páginasTextdocumentSaurabh SihagAinda não há avaliações

- How To Prepare Adjusting Entries - Step-By-Step (2023)Documento10 páginasHow To Prepare Adjusting Entries - Step-By-Step (2023)Yaseen GhulamAinda não há avaliações