Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Hinman Part1

Enviado por

Jason TuttDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hinman Part1

Enviado por

Jason TuttDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal homepage:

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

www.elsevier.com/locate/issn/20954964

Available also online at www.sciencedirect.com.

Copyright 2015, Journal of Integrative Medicine Editorial Office.

E-edition published by Elsevier (Singapore) Pte Ltd. All rights reserved.

Commentary

The methodology flaws in Hinmans acupuncture

clinical trial, Part I: Design and results

interpretation

Arthur Yin Fan

McLean Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, PLC., Vienna, VA 22182, USA

Keywords: acupuncture; arthralgia; chronic knee pain; Hinman; Zelen design; clinical trial; statistics; flaws

Citation: Fan AY. The methodology flaws in Hinmans acupuncture clinical trial, Part I: Design and results

interpretation. J Integr Med. 2015; 13(2): 6568.

In the October 2014 edition of JAMA, Dr. Hinman and

her colleagues published an acupuncture clinical trial entitled

Acupuncture for Chronic Knee Pain: A Randomized

Clinical Trial and concluded that in patients older than

50 years with moderate or severe chronic knee pain, neither

laser nor needle acupuncture conferred benefit over sham

for pain or function. Our findings do not support acupuncture

for these patients[1].

The author strongly disagrees with this conclusion, as

there were serious flaws in the trial design, the statistical

analysis of the data and in the interpretation of the results

of this study. This commentary is prepared in two parts. In

Part I, the study design, acupuncture dose and interpretation

of results will be investigated. In Part II, the Zelen design

and dilution effect will be discussed.

negative control (sham intervention group) and, if possible,

with a positive control group, in which this positive control

has already been tested as an effective therapy[2,3]. In

Hinman et als study [1], there are four groups: control

group, conventional or needle acupuncture group, laser

acupuncture group and sham laser acupuncture group.

Obviously, in this RCT, the major testing factor is laser

acupuncture; acupuncture served as a positive control.

This is supported by evidence found outside of the article

in question. Dr. Lao et al[4] and Dr. Li[5] pointed out that the

authors registered this trial as testing laser acupuncture,

instead of conventional acupuncture[6,7]. There has also

been strong evidence that acupuncture is an effective

therapy for chronic knee pain[2,3]. Thus, acupuncture should

have served as the positive control in this trial.

If acupuncture was the major testing factor as the article

title indicated[1], it should have had the proper control

groups. In this trial with a Zelen design, the patients in the

control (non-intervention) group did not have informed

consent, but the patients in the acupuncture group did

have informed consent. This means that there were

differences in informed consent among the groups (i.e.,

not matched), so there was no comparability between

these groups as the patients were not blinded. Moreover,

the sham laser acupuncture group actually could not be

treated as a valid negative control for the acupuncture

1 There is a major mistake in the primary testing

factor in this RCT: the laser acupuncture should be

the primary testing factor, not the needle acupuncture

In a vigorous randomized controlled trial (RCT), there

is a primary testing factor or objective. An example of a

major or primary testing factor could be a new therapy

of unknown efficacy. The major testing factor should

be compared with a non-intervention group, or what is

commonly known as a control group (or Nave group),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60170-4

Received February 20, 2015; accepted March 5, 2015.

Correspondence: Arthur Yin Fan, CMD, PhD, LAc; Tel: +1-703-499-4428; E-mail: ArthurFan@ChineseMedicineDoctor.US

Journal of Integrative Medicine

65

March 2015, Vol.13, No.2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

treatment, because these two interventions do not have

comparability in both characteristics and form (i.e., not

matched). Also, there was no blinding method performed

between these two groups, because both the patients and

the administrators who performed the interventions knew

the difference between the groups, such as needling acupuncture and sham laser acupuncture; in contrast, there

was only blinding between laser acupuncture and sham

laser acupuncture (i.e., matched, to some extent). The

laser acupuncture instead of the needle acupuncture was

the primary or major testing factor; if acupuncture was the

primary testing factor, as Hinman emphasized, the quality

of this trial would be very poor, because the trial does not

follow the scientific principle for an RCT[810], as there was

neither any blinding used nor correct control groups for

such an acupuncture clinical trial.

It is improper to test two different testing factors in one

RCT[810], such as both laser acupuncture and acupuncture,

as was reported in this study design[1]. One could suggest

that Hinman intended to confuse readers in this article;

she claimed the trial was to test both acupuncture and

laser acupuncture. However, in the title of the article,

she clearly stated acupuncture for chronic knee pain: a

randomized clinical trial, which suggests that acupuncture

was the primary testing factor not laser acupuncture.

dose (i.e., the stimulation or duration of the laser or needle

was not enough to induce an effect, such as would be

recommended in other trials on the same interventions),

the sample sizes were too small, or the results found were

due to other methodological flaws. Based on the design

and the statistics, there is no reason to compare the acupuncture group with the sham laser acupuncture group (a

tested or positive control vs. a negative control); further,

these two styles of interventions are not comparable.

Should the researchers want to look at the effectiveness

of conventional, needle acupuncture, a separate design or

study would be needed in order to get valid results. Acupuncture and laser acupuncture are two separate interventions

that would need two separate control groups. Comparing

the primary intervention, acupuncture, to results from the

negative control group of a different intervention (sham

laser acupuncture) may cloud statistical results.

In fact, in the original article, there is a significant difference

between the acupuncture group and the control group

with regards to the Overall Pain score and Western Ontario

and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; both

were P<0.05 at week 12 of the study. This means that

acupuncture did decrease pain intensity and improve

function in patients with chronic knee pain. However, the

author did not interpret or report this crucial information.

Furthermore, the concept of laser acupuncture should not

be mixed with acupuncture. Laser acupuncture does not

involve a needle, or instrument piercing of the skin; therefore,

the authors conclusions about the ineffectiveness of laser

acupuncture should not be applied to acupuncture.

One could conclude that Dr. Hinman misleads readers

by testing acupuncture as a major intervention in this

RCT. There was no significance between the positive

control and the nave control (i.e., acupuncture and control

groups). Therefore, we can only conclude that the positive

control, acupuncture was under-dosed or the study was

otherwise flawed. That the positive control shows significance

is a basic sign of the success of a clinical trial. From this

perspective, Hinmans trial was a failed clinical trial for

laser acupuncture. As it would be unethical to publish an

astonishing article, with a group of almost scrapped data

and confusing logic, that misleads the readers, including

the general public, medical society and policy makers, the

researchers should have re-adjusted or re-designed their

study instead of publishing it.

2 The interpretation of the results was misleading

Let us assume that the data and statistic work are all

correct in the original article.

2.1 There is no significant difference between the laser

acupuncture group and the control group, or between

the laser acupuncture group and the sham laser acupuncture group

From this statement, two conclusions are possible. Either

laser acupuncture is not effective, or the strength or concentration of the laser acupuncture treatment has not elicited

a response. One can also theorize that perhaps there were

other variables at play. This interpretation only looks at the

results from the laser acupuncture, non-intervention and

sham laser acupuncture groups. This interpretation of the

results cannot speak to the efficacy of needle acupuncture

in the treatment of knee pain. Again, one must also consider

that there could have been other factors that influenced

the study results. One must also verify that the laser acupuncture used was as effective as possible (i.e., timing or

duration of the treatment or stimulation).

2.2 There is no significant difference in the results between

the laser acupuncture group and the acupuncture group,

and at the same time, there was no significant difference

between the laser acupuncture group and the control group

It is possible that the treatments in the acupuncture and/

or the laser acupuncture groups were not used at an optimal

March 2015, Vol.13, No.2

3 The under-dosed acupuncture treatments

diluted the potential real effectiveness of acupuncture

In the article[1], the acupuncture treatments were 20 minute

treatments that were delivered once or twice weekly for

12 weeks, with 8 to 12 sessions in total permitted. This

66

Journal of Integrative Medicine

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

means that in the acupuncture group, the patients received

0, 1 or 2 acupuncture treatments per week, in which a total

of 812 sessions were allowed. The fact that each patient

received a different number of treatments plays a factor

in the results. Further, the treatment time was very short.

Often, acupuncture treatments last longer than 20 min

per session on average. Finally, there are other important

details about the treatment, such as depth of needle

insertion and the deqi technique, that were not mentioned

in the publication. Needling depth and needling technique

(i.e., manipulation) are very important in acupuncture

and those practicing in the acupuncture field would agree

that these details would also influence the effectiveness

of treatment. This acupuncture dose (by which is meant

number of sessions) is significantly less than the doses

in published acupuncture RCTs on chronic knee pain

(or other chronic pain) [2,3]. In licensed acupuncturists

daily practices, practitioners use 45-minute acupuncture

treatments, at least twice per week for 12 weeks. Practitioners also use a deeper stimulation and deqi technique.

The acupuncture treatments in this paper were, at most,

sub-optimal.

any intervention (i.e., laser acupuncture, sham laser

acupuncture or acupuncture), this would equate them

to those in the control group who also did not receive

any intervention. (Dr. Fan notes: in all groups, patients

were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

without reporting dosage and frequency in the original

study [1].) The new mean(s) calculation needs to consider

eliminating the influence of the patients who did not get the

intervention, from the original mean. For example, in the

acupuncture group with 64 patients (used in the original

article), the total Overall Pain score was: 3.364=211.2;

the total Overall Pain score in the ten drop-out patients

was: 4.410=44; then in the acupuncture group with 54

patients, the total Overall Pain score should be: 211.244=167.2. The new mean will be: 167.2/54=3.09.

We can get new means and standard deviations for the

laser acupuncture, sham laser acupuncture and acupuncture

groups for re-calculating the P value (Table 1).

Although the doses (treatment quality and quantity)

used were sub-optimal, as compared to other studies[2,3,11],

both laser acupuncture and acupuncture were actually

effective in decreasing Overall Pain score at week 12

(both P<0.01; Table 1). The new results show that

acupuncture is more effective than laser acupuncture,

and that laser acupuncture is more effective than both the

sham laser acupuncture and the control. However, sham

laser acupuncture also seems to be effective (P<0.01); the

reason why it is effective needs further investigation.

Compared with the sham laser acupuncture (the negative

control), or the acupuncture (the positive control), there

are no statistical differences either between the laser

acupuncture and the sham acupuncture, or between the

laser acupuncture and the acupuncture. This phenomenon

suggests that the original data need to be re-grouped and

re-analyzed. If the authors realized that the quality of the

current reported trial[1] is poor and cannot be fixed, the

RCT should be re-designed and re-conducted.

4 Laser acupuncture and acupuncture would be

effective in Hinmans RCT, if the statistics were

re-analyzed after re-adjusting the data

The original raw data could not be provided by the authors,

so it is difficult to re-conduct an analysis of variance test

to compare the differences among the groups; a student-t

test was used for the purposes of this article instead. The

data of the overall pain from Table 2 in the original paper[1]

were re-adjusted and re-present in Table 1 (the analysis

for other parameters are omitted to save space). Some

data was switched to the control group (this included the

21 participants who did not receive any treatment although

they were originally allocated to the intervention groups).

Thus, the new sample sizes are 90, 58, 54 and 54 in the

control, laser acupuncture, sham laser acupuncture and

acupuncture groups, respectively. Assuming that these 21

cases have the same mean (4.4) and standard deviation

(2.4) as those in the control group, as they did not receive

5 Acknowledgements

Dr. Arthur Yin Fan would like to thank Ms. Sarah Faggert

for editing support.

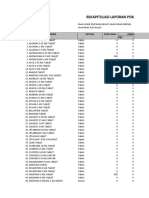

Table 1 Comparison of four groups at week 12, with the pain score, and P value

Group

Served as

Compared with the control

Sample

size (n)

Mean

Standard

deviation

t value*

P value

Control

Naive control

90

4.40

2.4

n/a

Laser acupuncture

Major testing factor

58

3.28

2.2

2.90

<0.01

Sham laser acupuncture

Negative control

54

3.33

2.2

2.68

<0.01

Acupuncture

Positive control

54

3.09

2.2

3.34

<0.01

[1]

Analysis of variance could not be conducted due to original data could not be got from the author .

Journal of Integrative Medicine

67

March 2015, Vol.13, No.2

www.jcimjournal.com/jim

6 Competing interests

Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M, Relf I, Crossley KM,

Reddy P, Forbes A, Harris A, Metcalf BR, Kyriakides M,

Novy K, Bennell KL. Efficacy of acupuncture for chronic

knee pain: protocol for a randomized controlled trial using

a Zelen design. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012; 12:

161.

7 Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Acupuncture

for chronic knee pain trial [registry identifier: ACTRN12609001001280]. [2015-02-22]. https://anzctr.org.au/

Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=308156.

8 Consort Transparent Reporting of Trials. Consort 2010: Trial

design. [2015-03-09]. http://www.consort-statement.org/

checklists/view/32-consort/72-trial-design.

9 National Health Institutes. Quality Assessment of Controlled

Intervention Studies. Systematic evidence reviews & clinical

practice guidelines. [2015-03-04]. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/

health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/

tools/rct.

10 West A, Spring B. Randomized controlled trials. [201503-09]. http://www.ebbp.org/course_outlines/randomized_

controlled_trials/

11 Baxter GD, Tumilty S. Treating chronic knee pain with acupuncture. JAMA. 2015; 313(6): 626627.

The author is an independent researcher, and declares

that he has no competing interests.

REFERENCES

1

3

4

5

Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M, Relf I, Forbes A, Crossley

KM, Williamson E, Kyriakides M, Novy K, Metcalf BR,

Harris A, Reddy P, Conaghan PG, Bennell KL. Acupuncture

for chronic knee pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

2014; 312(13): 13131322.

Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, Lee WL, Gilpin AM,

Hochberg MC. Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive

therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141(12): 901910.

Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA.

2014; 311(9): 955956.

Lao L, Yeung WF. Treating chronic knee pain with acupuncture. JAMA. 2015; 313(6): 627628.

Li YM. Treating chronic knee pain with acupuncture. JAMA.

2015; 313(6): 628.

Submission Guide

Journal of Integrative Medicine (JIM) is an international,

peer-reviewed, PubMed-indexed journal, publishing papers

on all aspects of integrative medicine, such as acupuncture

and traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, herbal

medicine, homeopathy, nutrition, chiropractic, mind-body

medicine, Taichi, Qigong, meditation, and any other modalities

of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Article

No submission and page charges

types include reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses,

randomized controlled and pragmatic trials, translational and

patient-centered effectiveness outcome studies, case series and

reports, clinical trial protocols, preclinical and basic science

studies, papers on methodology and CAM history or education,

editorials, global views, commentaries, short communications,

book reviews, conference proceedings, and letters to the editor.

Quick decision and online first publication

For information on manuscript preparation and submission, please visit JIM website. Send your postal address by e-mail to

jcim@163.com, we will send you a complimentary print issue upon receipt.

March 2015, Vol.13, No.2

68

Journal of Integrative Medicine

Você também pode gostar

- CCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Interviewing Tool 2014 enDocumento130 páginasCCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Interviewing Tool 2014 enJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- CCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Interviewing Guide 2014 enDocumento11 páginasCCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Interviewing Guide 2014 enJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- So Pa 304903Documento3 páginasSo Pa 304903Jason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Blue BlehhhhDocumento1 páginaBlue BlehhhhJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- 12Documento2 páginas12Jason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Are Manual Therapies, Passive Physical Modalities, or Acupuncture Effective For The Management of Patients With Whiplash-Associated Disorders or Neck Pain and Associated DisordersDocumento90 páginasAre Manual Therapies, Passive Physical Modalities, or Acupuncture Effective For The Management of Patients With Whiplash-Associated Disorders or Neck Pain and Associated DisordersJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- 12Documento2 páginas12Jason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- CCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Performance Management Tool 2014 enDocumento61 páginasCCSA Workforce Behavioural Competencies Performance Management Tool 2014 enJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- 12Documento2 páginas12Jason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Document RandoDocumento2 páginasDocument RandoJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Spiffle SpaffleDocumento2 páginasSpiffle SpaffleJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- RektDocumento1 páginaRektJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Journal of DentistryDocumento7 páginasIndian Journal of DentistryJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Navin Et Al - 2000Documento5 páginasNavin Et Al - 2000Jason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Ongoing Positive Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Corticosteroid Injection in Lateral Epicondylitis - 2 Year FollowupDocumento10 páginasOngoing Positive Effect of Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Corticosteroid Injection in Lateral Epicondylitis - 2 Year FollowupJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Pathogenic Gut Flora Tied To Heart Failure SeverityDocumento3 páginasPathogenic Gut Flora Tied To Heart Failure SeverityJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Research Strategies For Establishing An Evidence Base Hugh MacPherson Richard Hammerschlag George Lewitt Rosa Schnyer PDFDocumento273 páginasAcupuncture Research Strategies For Establishing An Evidence Base Hugh MacPherson Richard Hammerschlag George Lewitt Rosa Schnyer PDFJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Autologous Blood Versus Steroid Injection in Lateral EpicondylitisDocumento12 páginasPlatelet-Rich Plasma Versus Autologous Blood Versus Steroid Injection in Lateral EpicondylitisJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- BMO Prepaid Travel Cardholder Agreement enDocumento2 páginasBMO Prepaid Travel Cardholder Agreement enJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Dry Needling Resource PaperDocumento4 páginasDry Needling Resource PaperJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- The New Zealand Medical Journal: A Case of Acupuncture-Induced PneumothoraxDocumento3 páginasThe New Zealand Medical Journal: A Case of Acupuncture-Induced PneumothoraxJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Platelet Rich Plasma Therapy - A Comparative Effective Therapy With Promising Results in Plantar FasciitisDocumento5 páginasPlatelet Rich Plasma Therapy - A Comparative Effective Therapy With Promising Results in Plantar FasciitisJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Ling Shu - CompressedDocumento353 páginasLing Shu - CompressedJason Tutt100% (18)

- HBS Press Release - The Effect of File Sharing On Record SalesDocumento2 páginasHBS Press Release - The Effect of File Sharing On Record SalesJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- DryNeedlingInClinicalPractice ResourcePaperDocumento7 páginasDryNeedlingInClinicalPractice ResourcePaperJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- DryNeedlingInClinicalPractice ResourcePaperDocumento7 páginasDryNeedlingInClinicalPractice ResourcePaperJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Defining Adequate Dose of AcupunctureDocumento11 páginasDefining Adequate Dose of AcupunctureJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Induced Pneumothorax - A Case ReportDocumento1 páginaAcupuncture Induced Pneumothorax - A Case ReportJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Induced Pneumothorax - A Case ReportDocumento1 páginaAcupuncture Induced Pneumothorax - A Case ReportJason TuttAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Acute Pain Questions - LathaDocumento5 páginasAcute Pain Questions - LathaNishanth yedavalliAinda não há avaliações

- Therapy Program OASESDocumento8 páginasTherapy Program OASESVedashri1411100% (1)

- Crossword PuzzleDocumento2 páginasCrossword PuzzleJohn Patric Plaida100% (1)

- 21 Employee Benefits Cas. 1250, Pens. Plan Guide (CCH) P 23935u Nancy Martin v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Virginia, Inc., 115 F.3d 1201, 4th Cir. (1997)Documento15 páginas21 Employee Benefits Cas. 1250, Pens. Plan Guide (CCH) P 23935u Nancy Martin v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Virginia, Inc., 115 F.3d 1201, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- ICF Model For Parkinson's DiseaseDocumento8 páginasICF Model For Parkinson's Diseasehelsil01Ainda não há avaliações

- 5014-Prescription Regulation TableDocumento2 páginas5014-Prescription Regulation TableUrugonda VenumadhavAinda não há avaliações

- Fentanyl Fact Sheet 508c 1Documento2 páginasFentanyl Fact Sheet 508c 1api-160935984Ainda não há avaliações

- Pharmacy Books CupboardDocumento18 páginasPharmacy Books CupboardM Asif baloch100% (2)

- Refresher Course For Registered PharmacistDocumento1 páginaRefresher Course For Registered PharmacistThe Unknown 97Ainda não há avaliações

- PT Price ListDocumento2 páginasPT Price ListkokobonyAinda não há avaliações

- TubeDocumento7 páginasTubeRAFIQAHNURIAinda não há avaliações

- Art Therapy Benefits in Occupational SettingsDocumento5 páginasArt Therapy Benefits in Occupational SettingsCristobal BianchiAinda não há avaliações

- Compiled DocumentDocumento261 páginasCompiled DocumentAbhigyan Kishor100% (1)

- Eficácia Da Musicoterapia Improvisacional Musicocentrada No Tratamento Decrianças Pré-Escolares No Espectro Do AutismoDocumento29 páginasEficácia Da Musicoterapia Improvisacional Musicocentrada No Tratamento Decrianças Pré-Escolares No Espectro Do AutismodaniellegarciaaaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Write Up WorksheetDocumento7 páginasCase Write Up WorksheetWellingtonFaijãoAinda não há avaliações

- Technical Specifications Neumovent TsSW15Documento9 páginasTechnical Specifications Neumovent TsSW15Ahmed zakiAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Prescribing and Dispensing Pattern in PediatrDocumento6 páginasDrug Prescribing and Dispensing Pattern in PediatrAestherielle SeraphineAinda não há avaliações

- Rekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFDocumento9 páginasRekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika: NO Nama Satuan Stok Awal Pemasukan PBFlarasAinda não há avaliações

- 9 - New Drug Development PlanDocumento27 páginas9 - New Drug Development PlanUmair MazharAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Management of Childhood Illness IntroductionDocumento27 páginasIntegrated Management of Childhood Illness IntroductionKevin LockwoodAinda não há avaliações

- AtlasDocumento1 páginaAtlasSohail AAinda não há avaliações

- The Family System in 40 CharactersDocumento5 páginasThe Family System in 40 CharactersRose Andrea De los SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Lilia Kappas, Administratrix of the Estate of Florence Kappas, Deceased v. Chestnut Lodge, Inc. Jaime Buenaventura, M.D. Dexter M. Bullard, Jr., M.D. Dexter M. Bullard, Sr., M.D. Corrinne Cooper, M.D. Martin Cooperman, M.D. Jerry Dowling, M.D. John P. Fort, M.D. Oswoldo Guimaraes, M.D. Sol Herman, M.D. Elizabeth Mohler Ping-Nie Pao, M.D. Dewayne Phillips, M.D. Jonathan Tuerk, M.D. And Otto Will, M.D., and Robert R. Montgomery, M.D. John C. Saia, M.D. And Suburban Hospital Association, Inc., 709 F.2d 878, 4th Cir. (1983)Documento6 páginasLilia Kappas, Administratrix of the Estate of Florence Kappas, Deceased v. Chestnut Lodge, Inc. Jaime Buenaventura, M.D. Dexter M. Bullard, Jr., M.D. Dexter M. Bullard, Sr., M.D. Corrinne Cooper, M.D. Martin Cooperman, M.D. Jerry Dowling, M.D. John P. Fort, M.D. Oswoldo Guimaraes, M.D. Sol Herman, M.D. Elizabeth Mohler Ping-Nie Pao, M.D. Dewayne Phillips, M.D. Jonathan Tuerk, M.D. And Otto Will, M.D., and Robert R. Montgomery, M.D. John C. Saia, M.D. And Suburban Hospital Association, Inc., 709 F.2d 878, 4th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Pembelian FebruariDocumento14 páginasPembelian FebruariBoy ReynaldiAinda não há avaliações

- PK & Bioavailability Study of DrugsDocumento32 páginasPK & Bioavailability Study of Drugsmursidstone.mursid50% (2)

- Mood Management Course - 02 - Depression Cognitive Behavioural TherapyDocumento3 páginasMood Management Course - 02 - Depression Cognitive Behavioural TherapyBlanca De Miguel CabrejasAinda não há avaliações

- Gynisol SyrupDocumento2 páginasGynisol Syruphk_scribdAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Pharmacology and Clinical PharmacyDocumento8 páginasClinical Pharmacology and Clinical PharmacyRowena Concepcion Penafiel100% (1)

- Injeksi BookDocumento13 páginasInjeksi BookSyarif SamAinda não há avaliações

- Burzynski Cancer Healer Anti Neo PlastonsDocumento3 páginasBurzynski Cancer Healer Anti Neo PlastonsyoyomamanAinda não há avaliações