Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Cuison v. Ca2

Enviado por

Jennilyn TugelidaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Cuison v. Ca2

Enviado por

Jennilyn TugelidaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

VOL. 227, OCTOBER 26, 1993

391

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

*

G.R. No. 88539. October 26, 1993.

KUE CUISON, doing business under the firm name and

style KUE CUISON PAPER SUPPLY, petitioner, vs. THE

COURT OF APPEALS, VALIANT INVESTMENT

ASSOCIATES, respondents.

Remedial Law; Appeal; It is elementary that in petitions for

review under Rule 45, the Court only passes upon questions of law.

This petition ought to have been denied outright, for in the final

analysis, it raises a factual issue. It is elementary that in petitions

for review under Rule 45, this Court only passes upon questions of

law. An exception thereto occurs where the findings of fact of the

Court of Appeals are at variance with the trial court, in which case

the Court reviews the evidence in order to arrive at the correct

findings based on the records.

Same; Evidence; Self-serving evidence is evidence made by a

party out of court at one time, it does not include a partys testimony

as a witness in court.The argument that Villanuevas testimony is

self-serving and therefore inadmissible on the lame excuse of his

employment with private respondent utterly misconstrues the

nature of self-serving evidence and the specific ground for its

exclusion. As pointed out by this Court in Co v. Court of Appeals, et

al., (99 SCRA 321 [1980]):

_______________

*

THIRD DIV ISION.

392

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

1/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

392

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

Self-serving evidence is evidence made by a party out of court at

one time; it does not include a partys testimony as a witness in

court. It is excluded on the same ground as any hearsay evidence,

that is the lack of opportunity for cross-examination by the adverse

party, and on the consideration that its admission would open the

door to fraud and to fabrication of testimony. On the other hand, a

partys testimony in court is sworn and affords the other party the

opportunity for cross-examination (italics supplied).

Same; Same; Same; If a mans extrajudicial admissions are

admissible against him, there seems to be no reason why his

admissions made in open court, under oath, should not be accepted

against him.Furthermore, consistent with and as an obvious

indication of, the fact that Tiu Huy Tiac was the manager of the

Sto. Cristo branch, three (3) months after Tiu Huy Tiac left

petitioners employ, petitioner even sent communications to its

customers notifying them that Tiu Huy Tiac is no longer connected

with petitioners business. Such undertaking spoke unmistakenly of

Tiu Huy Tiacs valuable position as petitioners manager than any

uttered disclaimer. More than anything else, this act taken together

with the declaration of petitioner in-open court amount to

admissions under Rule 130 Section 22 of the Rules of Court, to wit:

The act, declaration or omission of a party as to a relevant fact may

be given in evidence against him. For well-settled is the rule that a

mans acts, conduct and declaration, wherever made, if voluntary,

are admissible against him, for the reason that it is fair to presume

that they correspond with the truth, and it is his fault if they do not.

If a mans extrajudicial admissions are admissible against him,

there seems to be no reason why his admissions made in open court,

under oath, should not be accepted against him.

Civil Law; Agency; One who clothes another with apparent

authority as his agent and holds him out to the public as such

cannot be permitted to deny the authority of such person to act as

his agent to the prejudice of innocent third parties dealing with

such person in good faith and in the honest belief that he is what

he appears to be.As to the merits of the case, it is a wellestablished rule that one who clothes another with apparent

authority as his agent and holds him out to the public as such

cannot be permitted to deny the authority of such person to act as

his agent, to the prejudice of innocent third parties dealing with

such person in good faith and in the honest belief that he is what he

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

2/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

appears to be (Macke, et al. v. Camps, 7 Phil. 553 [1907]; Philippine

National Bank v. Court of Appeals, 94 SCRA 357 [1979]). From the

facts and the evidence on record, there is no doubt that this rule

obtains. The petition must therefore fail.

393

VOL. 227, OCTOBER 26, 1993

393

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

Same; Same; Even when the agent has exceeded his authority,

the principal is solidarily liable with the agent if the former

allowed the latter to act as though he had full powers.Taken in

this light, petitioner is liable for the transaction entered into by Tiu

Huy Tiac on his behalf. Thus, even when the agent has exceeded

his authority, the principal is solidarily liable with the agent if the

former allowed the latter to act as though he had full powers

(Article 1911 Civil Code), as in the case at bar.

Same; Estoppel; A party cannot be allowed to go back on his

own acts and representations to the prejudice of the other party who

in good faith relied upon them.Tiu Huy Tiac, therefore, by

petitioners own representations and manifestations, became an

agent of petitioner by estoppel. Under the doctrine of estoppel, an

admission or representation is rendered conclusive upon the person

making it, and cannot be denied or disproved as against the person

relying thereon (Article 1431, Civil Code of the Philippines). A party

cannot be allowed to go back on his own acts and representations to

the prejudice of the other party who, in good faith, relied upon

them.

Same; Same; Same; As between two innocent parties, the one

who made it possible for the wrong to be done should be the one to

bear the resulting loss.Finally, although it may appear that Tiu

Huy Tiac defrauded his principal (petitioner) in not turning over

the proceeds of the transaction to the latter, such fact cannot in any

way relieve nor exonerate petitioner of his liability to private

respondent. For it is an equitable maxim that as between two

innocent parties, the one who made it possible for the wrong to be

done should be the one to bear the resulting loss.

PETITION for review of a decision of the Court of Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Leighton R. Siazon for petitioner.

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

3/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

Melanio L. Zoreta for private respondent.

BIDIN, J.:

This petition for review assails the decision of the

respondent Court of Appeals ordering petitioner to pay

private respondent, among others, the sum of P297,482.30

with interest. Said decision reversed the appealed decision of

the trial court rendered in favor of petitioner.

394

394

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

The case involves an action for a sum of money filed by

respondent against petitioner anchored on the following

antecedent facts:

Petitioner Kue Cuison is a sole proprietorship engaged in

the purchase and sale of newsprint, bond paper and scrap,

with places of business at Baesa, Quezon City, and Sto.

Cristo, Binondo, Manila. Private respondent Valiant

Investment Associates, on the other hand, is a partnership

duly organized and existing under the laws of the

Philippines with business address at Kalookan City.

From December 4, 1979 to February 15, 1980, private

respondent delivered various kinds of paper products

amounting to P297,487.30 to a certain Lilian Tan of LT

Trading. The deliveries were made by respondent pursuant

to orders allegedly placed by Tiu Huy Tiac who was then

employed in the Binondo office of petitioner. It was likewise

pursuant to Tiacs instructions that the merchandise was

delivered to Lilian Tan. Upon delivery, Lilian Tan paid for

the merchandise by issuing several checks payable to cash

at the specific request of Tiu Huy Tiac. In turn, Tiac issued

nine (9) postdated checks to private respondent as payment

for the paper products. Unfortunately, said checks were later

dishonored by the drawee bank.

Thereafter, private respondent made several demands

upon petitioner to pay for the merchandise in question,

claiming that Tiu Huy Tiac was duly authorized by

petitioner as the manager of his Binondo office, to enter into

the questioned transactions with private respondent and

Lilian Tan. Petitioner denied any involvement in the

transaction entered into by Tiu Huy Tiac and refused to pay

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

4/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

private respondent the amount corresponding to the selling

price of the subject merchandise.

Left with no recourse, private respondent filed an action

against petitioner for the collection of P297,487.30

representing the price of the merchandise. After due

hearing, the trial court dismissed the complaint against

petitioner for lack of merit. On appeal, however, the decision

of the trial court was modified, but was in effect reversed by

the Court of Appeals, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is MODIFIED in that

defendant-appellant Kue Cuison is hereby ordered to pay plaintiff395

VOL. 227, OCTOBER 26, 1993

395

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

appellant Valiant Investment Associates the sum of P297,487.30

with 12% interest from the filing of the complaint until the amount

is fully paid, plus the sum of 7% of the total amount due as

attorneys fees, and to pay the costs. In all other respects, the

decision appealed from is affirmed. (Rollo, p. 55)

In this petition, petitioner contends that:

THE HONORABLE COURT ERRED IN FINDING TIU HUY TIAC

AGENT OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT CONTRARY TO THE

UNDISPUTED/ESTABLISHED FACTS AND CIRCUMSTANCES.

THE

HONORABLE

COURT ERRED

IN

FINDING

DEFENDANT-APPELLANT LIABLE FOR AN OBLIGATION

UNDISPUTABLY BELONGING TO TIU HUY TIAC.

THE HONORABLE COURT ERRED IN REVERSING THE

WELL-FOUNDED DECISION OF THE TRIAL COURT. (Rollo, p.

19)

The issue here is really quite simple, and that iswhether

or not Tiu Huy Tiac possessed the required authority from

petitioner sufficient to hold the latter liable for the disputed

transaction.

This petition ought to have been denied outright, for in

the final analysis, it raises a factual issue. It is elementary

that in petitions for review under Rule 45, this Court only

passes upon questions of law. An exception thereto occurs

where the findings of fact of the Court of Appeals are at

variance with the trial court, in which case the Court

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

5/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

reviews the evidence in order to arrive at the correct

findings based on the records.

As to the merits of the case, it is a well-established rule

that one who clothes another with apparent authority as his

agent and holds him out to the public as such cannot be

permitted to deny the authority of such person to act as his

agent, to the prejudice of innocent third parties dealing with

such person in good faith and in the honest belief that he is

what he appears to be (Macke, et al. v. Camps, 7 Phil. 553

[1907]; Philippine National Bank v. Court of Appeals, 94

SCRA 357 [1979]). From the facts and the evidence on

record, there is no doubt that this rule obtains. The petition

must therefore fail.

It is evident from the records that by his own acts and

admission, petitioner held out Tiu-Huy Tiac to the public as

the manager of his store in Sto. Cristo, Binondo, Manila.

More

396

396

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

particularly, petitioner explicitly introduced Tiu Huy Tiac

to Bernardino Villanueva, respondents manager, as his

(petitioners) branch manager as testified to by Bernardino

Villanueva. Secondly, Lilian Tan, who has been doing

business with petitioner for quite a while, also testified that

she knew Tiu Huy Tiac to be the manager of petitioners Sto.

Cristo, Binondo branch. This general perception of Tiu Huy

Tiac as the manager of petitioners Sto. Cristo store is even

made manifest by the fact that Tiu Huy Tiac is known in the

community to be the kinakapatid (godbrother) of

petitioner. In fact, even petitioner admitted his close

relationship with Tiu Huy Tiac when he said in open court

that they are like brothers (Rollo, p. 54). There was thus no

reason for anybody especially those transacting business

with petitioner to even doubt the authority of Tiu Huy Tiac

as his manager in the Sto. Cristo, Binondo branch.

In a futile attempt to discredit Villanueva, petitioner

alleges that the formers testimony is clearly self-serving

inasmuch as Villanueva worked for private respondent as

its manager.

We disagree. The argument that Villanuevas testimony

is self-serving and therefore inadmissible on the lame

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

6/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

excuse of his employment with private respondent utterly

misconstrues the nature of self-serving evidence and the

specific ground for its exclusion. As pointed out by this

Court in Co v. Court of Appeals, et al., (99 SCRA 321

[1980]):

Self-serving evidence is evidence made by a party out of court at

one time; it does not include a partys testimony as a witness in

court. It is excluded on the same ground as any hearsay evidence,

that is the lack of opportunity for cross-examination by the adverse

party, and on the consideration that its admission would open the

door to fraud and to fabrication of testimony. On the other hand, a

partys testimony in court is sworn and affords the other party the

opportunity for cross-examination (italics supplied).

Petitioner cites Villanuevas failure, despite his commitment

to do so on cross-examination, to produce the very first

invoice of the transaction between petitioner and private

respondent as another ground to discredit Villanuevas

testimony. Such failure, petitioner argues, proves that

Villanueva was not only bluffing when he pretended that he

can produce the invoice, but that Villanueva was likewise

prevaricating when he insisted that

397

VOL. 227, OCTOBER 26, 1993

397

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

such prior transactions actually took place. Petitioner is

mistaken. In fact, it was petitioners counsel himself who

withdrew the reservation to have Villanueva produce the

document in court. As aptly observed by the Court of

Appeals in its decision:

x x x However, during the hearing on March 3, 1981, Villanueva

failed to present the document adverted to because defendantappellants counsel withdrew his reservation to have the former

(Villanueva) produce the document or invoice, thus prompting

plaintiff-appellant to rest its case that same day (t.s.n., pp. 39-40,

Sess. of March 3, 1981). Now, defendant-appellant assails the

credibility of Villanueva for having allegedly failed to produce even

one single document to show that plaintiff-appellant and defendantappellant have had transactions before, when in fact said failure of

Villanueva to produce said document is a direct off-shoot of the

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

7/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

action of defendant-appellants counsel who withdrew his

reservation for the production of the document or invoice and which

led plaintiff-appellant to rest its case that very day. (Rollo, p. 52)

In the same manner, petitioner assails the credibility of

Lilian Tan by alleging that Tan was part of an intricate plot

to defraud him. However, petitioner failed to substantiate or

prove that the subject transaction was designed to defraud

him. Ironically, it was even the testimony of petitioners

daughter and assistant manager Imelda Kue Cuison which

confirmed the credibility of Tan as a witness. On the witness

stand, Imelda testified that she knew for a fact that prior to

the transaction in question, Tan regularly transacted

business with her father (petitioner herein), thereby

corroborating Tans testimony to the same effect. As

correctly found by the respondent court, there was no logical

explanation for Tan to impute liability upon petitioner.

Rather, the testimony of Imelda Kue Cuison only served to

add credence to Tans testimony as regards the transaction,

the liability for which petitioner wishes to be absolved.

But of even greater weight than any of these testimonies,

is petitioners categorical admission on the witness stand

that Tiu Huy Tiac was the manager of his store in Sto.

Cristo, Binondo, to wit:

Court:

xxx

398

398

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

Q And who was managing the store in Sto. Cristo?

A At first it was Mr. Ang, then later Mr. Tiu Huy Tiac but

I cannot remember the exact year.

Q So, Mr. Tiu Huy Tiac took over the management.

A Not that was because every afternoon, I was there, sir.

Q But in the morning, who takes charge?

A Tiu Huy Tiac takes charge of management and if there

(sic) orders for newsprint or bond papers they are

always ref erred to the compound in Baesa, sir. (t.s.n.,

p. 16, Session of January 20, 1981, CA decision, Rollo, p.

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

8/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

50, italics supplied).

Such admission, spontaneous no doubt, and standing alone,

is sufficient to negate all the denials made by petitioner

regarding the capacity of Tiu Huy Tiac to enter into the

transaction in question. Furthermore, consistent with and

as an obvious indication of, the fact that Tiu Huy Tiac was

the manager of the Sto. Cristo branch, three (3) months

after Tiu Huy Tiac left petitioners employ, petitioner even

sent communications to its customers notifying them that

Tiu Huy Tiac is no longer connected with petitioners

business. Such undertaking spoke unmistakenly of Tiu Huy

Tiacs valuable position as petitioners manager than any

uttered disclaimer. More than anything else, this act taken

together with the declaration of petitioner in open court

amount to admissions under Rule 130, Section 22 of the

Rules of Court, to wit: The act, declaration or omission of a

party as to a relevant fact may be given in evidence against

him. For well-settled is the rule that a mans acts, conduct

and declaration, wherever made, if voluntary, are

admissible against him, for the reason that it is fair to

presume that they correspond with the truth, and it is his

fault if they do not. If a mans extrajudicial admissions are

admissible against him, there seems to be no reason why his

admissions made in open court, under oath, should not be

accepted against him. (U.S. vs. Ching Po, 23 Phil. 578, 583

[1912]).

Moreover, petitioners unexplained delay in disowning

the transactions entered into by Tiu Huy Tiac despite

several attempts made by respondent to collect the amount

from him, proved all the more that petitioner was aware of

the questioned transactions. Such omission was tantamount

to an admission by silence under Rule 130 Section 23 of the

Rules of Court, thus: Any act or declaration made in the

presence of and within the

399

VOL. 227, OCTOBER 26, 1993

399

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

observation of a party who does or says nothing when the

act or declaration is such as naturally to call for action or

comment if not true, may be given in evidence against him.

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

9/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

All of these point to the fact that at the time of the

transaction, Tiu Huy Tiac was admittedly the manager of

petitioners store in Sto. Cristo, Binondo. Consequently, the

transaction in question as well as the concomitant

obligation is valid and binding upon petitioner.

By his representations, petitioner is now estopped from

disclaiming liability for the transaction entered into by Tiu

Huy Tiac on his behalf. It matters not whether the

representations are intentional or merely negligent so long

as innocent third persons relied upon such representations

in good faith and for value. As held in the case of Manila

Remnant Co., Inc. v. Court of Appeals, (191 SCRA 622

[1990]):

More in point, we find that by the principle of estoppel, Manila

Remnant is deemed to have allowed its agent to act as though it had

plenary powers. Article 1911 of the Civil Code provides:

Even when the agent has exceeded his authority, the principal

is solidarily liable with the agent if the former allowed the latter to

act as though he had full powers. (Italics supplied).

The above-quoted article is new. It is intended to protect the

rights of innocent persons. In such a situation, both the principal

and the agent may be considered as joint tortfeasors whose liability

is joint and solidary.

Authority by estoppel has arisen in the instant case because by

its negligence, the principal, Manila Remnant, has permitted its

agent, AU. Valencia and Co., to exercise powers not granted to it.

That the principal might not have had actual knowledge of the

agents misdeed is of no moment.

Tiu Huy Tiac, therefore, by petitioners own representations

and manifestations, became an agent of petitioner by

estoppel. Under the doctrine of estoppel, an admission or

representation is rendered conclusive upon the person

making it, and cannot be denied or disproved as against the

person relying thereon (Article 1431, Civil Code of the

Philippines). A party cannot be allowed to go back on his

own acts and representations to the prejudice of the other

party who, in good faith, relied upon them (Philippine

National Bank v. Intermediate Appellate Court, et

400

400

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Cuison vs. Court of Appeals

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

10/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

al., 189 SCRA 680 [1990]).

Taken in this light, petitioner is liable for the transaction

entered into by Tiu Huy Tiac on his behalf. Thus, even

when the agent has exceeded his authority, the principal is

solidarity liable with the agent if the former allowed the

latter to act as though he had full powers (Article 1911 Civil

Code), as in the case at bar.

Finally, although it may appear that Tiu Huy Tiac

defrauded his principal (petitioner) in not turning over the

proceeds of the transaction to the latter, such fact cannot in

any way relieve nor exonerate petitioner of his liability to

private respondent. For it is an equitable maxim that as

between two innocent parties, the one who made it possible

for the wrong to be done should be the one to bear the

resulting loss (Francisco vs. Government Service Insurance

System, 7 SCRA 577 [1963]).

Inasmuch as the fundamental issue of the capacity or

incapacity of the purported agent Tiu Huy Tiac, has already

been resolved, the Court deems it unnecessary to resolve the

other peripheral issues raised by petitioner.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is hereby DENIED

for lack of merit. Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Feliciano (Chairman), Romero, Melo and Vitug, JJ.,

concur.

Petition denied.

Note.It is well-settled principle that the agent shall be

liable for the act or omission of the principal only if the

latter is undisclosed (Maritime Agencies & Services Inc. vs.

Court of Appeals, 187 SCRA 346).

o0o

401

Copyright 2015 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights reserved.

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

11/12

2/6/15

CentralBooks:Reader

central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/0000014b5cf65487d8729e82000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

12/12

Você também pode gostar

- 5 Pardo VS Hercules Lumber PDFDocumento3 páginas5 Pardo VS Hercules Lumber PDFNathalie BermudezAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine promissory note cases analyzedDocumento13 páginasPhilippine promissory note cases analyzedRufino Gerard MorenoAinda não há avaliações

- Preterit I OnDocumento4 páginasPreterit I Onnildin danaAinda não há avaliações

- Miciano vs. BrimoDocumento7 páginasMiciano vs. Brimoericjoe bumagatAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Bagunu Vs Sps. Aggabao and Acerit PDFDocumento8 páginas2 Bagunu Vs Sps. Aggabao and Acerit PDFShieremell DiazAinda não há avaliações

- Duque CaseDocumento11 páginasDuque CasebenbernAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 33174Documento16 páginasG.R. No. 33174Inter_vivosAinda não há avaliações

- Holy Trinity CollegeDocumento53 páginasHoly Trinity Collegeinno KalAinda não há avaliações

- Puno CaseDocumento9 páginasPuno CaseRA De JoyaAinda não há avaliações

- Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System vs. Act Theater, IncDocumento4 páginasMetropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System vs. Act Theater, IncRomy Ian LimAinda não há avaliações

- Almeda v. CA, 256 SCRA 292 (1996)Documento7 páginasAlmeda v. CA, 256 SCRA 292 (1996)Fides DamascoAinda não há avaliações

- Raniel v. JochicoDocumento6 páginasRaniel v. JochicoAstina85Ainda não há avaliações

- Francisco vs. Mallen, Jr.Documento10 páginasFrancisco vs. Mallen, Jr.poiuytrewq9115Ainda não há avaliações

- 011 Makati Sports Club Inc Vs Cheng PDFDocumento16 páginas011 Makati Sports Club Inc Vs Cheng PDFPol EboyAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 15 17 Case Digest CivproDocumento28 páginasRule 15 17 Case Digest CivprodayneblazeAinda não há avaliações

- 4) Development Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, 231 SCRA 370, G.R. No. 109937 March 21, 1994Documento6 páginas4) Development Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, 231 SCRA 370, G.R. No. 109937 March 21, 1994Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Dorotheo Vs CADocumento5 páginasDorotheo Vs CAMi-young SunAinda não há avaliações

- Republic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawDocumento9 páginasRepublic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawAnonymous WDEHEGxDhAinda não há avaliações

- Succession 1Documento33 páginasSuccession 1Ken Aliudin100% (1)

- Chapter 14-Legal Memorandum and Case BriefDocumento6 páginasChapter 14-Legal Memorandum and Case BriefJoy Krisia Mae TablizoAinda não há avaliações

- Acme Shoe, Rubber & Plastic Corp. v. CADocumento2 páginasAcme Shoe, Rubber & Plastic Corp. v. CAAgee Romero-ValdesAinda não há avaliações

- Title and Definitions: Chan Robles Virtual Law LibraryDocumento36 páginasTitle and Definitions: Chan Robles Virtual Law LibrarykimAinda não há avaliações

- Ra 9285 PDFDocumento7 páginasRa 9285 PDFNowell SimAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding SEBA certification processesDocumento9 páginasUnderstanding SEBA certification processesCars CarandangAinda não há avaliações

- DNA Test Dispute in Illegitimate Child CaseDocumento5 páginasDNA Test Dispute in Illegitimate Child CasepatrickAinda não há avaliações

- The Corporation Code of The PhilippinesDocumento42 páginasThe Corporation Code of The PhilippinesAaronAinda não há avaliações

- PVB Cannot Invoke Receivership as Fortuitous Event to Interrupt PrescriptionDocumento2 páginasPVB Cannot Invoke Receivership as Fortuitous Event to Interrupt PrescriptionCharlie BartolomeAinda não há avaliações

- Sy TiongDocumento27 páginasSy TiongPduys160% (1)

- Ra 9481Documento7 páginasRa 9481monmonmonmon21Ainda não há avaliações

- Mabuhay Holdings Corporation, Logistics Limited,: First DivisionDocumento19 páginasMabuhay Holdings Corporation, Logistics Limited,: First Divisionmarie janAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Litton Vs Hill and CeronDocumento10 páginas1 Litton Vs Hill and CeronHillary Grace TevesAinda não há avaliações

- Atty Ferrer on Trademark RightsDocumento5 páginasAtty Ferrer on Trademark RightsHeintje NopraAinda não há avaliações

- Patrimonio V GutierrezDocumento27 páginasPatrimonio V GutierrezHeidiAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine National Bank v. Hydro Resources Contractors Corporation G.R. No. 167530, March 13, 2013Documento4 páginasPhilippine National Bank v. Hydro Resources Contractors Corporation G.R. No. 167530, March 13, 2013PCpl Harvin jay TolentinoAinda não há avaliações

- De Borja vs. Vda. de de BorjaDocumento14 páginasDe Borja vs. Vda. de de Borjaasnia07Ainda não há avaliações

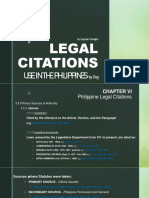

- Philippine Legal Citations SimplifiedDocumento13 páginasPhilippine Legal Citations SimplifiedLloyd Ian FongfarAinda não há avaliações

- de La Salle Montessori Int'l of Malolos, Inc. v. de La Sale Brothers, Inc., 855 SCRA 38 (2018)Documento15 páginasde La Salle Montessori Int'l of Malolos, Inc. v. de La Sale Brothers, Inc., 855 SCRA 38 (2018)bentley CobyAinda não há avaliações

- Reyes V Lim and Pemberton V de LimaDocumento2 páginasReyes V Lim and Pemberton V de LimaCheska Mae Tan-Camins WeeAinda não há avaliações

- RULE 13 Two ColumnsDocumento17 páginasRULE 13 Two ColumnsAnonymous jUM6bMUuRAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 172716Documento10 páginasG.R. No. 172716Andrina Binogwal TocgongnaAinda não há avaliações

- Elective (Seminar) - Course Syllabus. Atty. Fernandez (2nd Sem 2021)Documento4 páginasElective (Seminar) - Course Syllabus. Atty. Fernandez (2nd Sem 2021)Vincent TanAinda não há avaliações

- Nego Special AssignDocumento2 páginasNego Special AssignRupert VillaricoAinda não há avaliações

- SUCCESSION-mode of Acquisition byDocumento9 páginasSUCCESSION-mode of Acquisition byJohn Lester LantinAinda não há avaliações

- Barangay San Roque, Tlisay, Cebu v. Heirs of Francisco Pastor, GR No. 138896, June 20, 2000Documento4 páginasBarangay San Roque, Tlisay, Cebu v. Heirs of Francisco Pastor, GR No. 138896, June 20, 2000Ryan John NaragaAinda não há avaliações

- 2010 Bar Questions and Suggested Answers in Civil LawDocumento15 páginas2010 Bar Questions and Suggested Answers in Civil LawJim John David100% (1)

- Pilapil vs. Ibay-SomeraDocumento16 páginasPilapil vs. Ibay-SomeraAji AmanAinda não há avaliações

- Credit Transactions: Coverage For The First Half of The SemesterDocumento6 páginasCredit Transactions: Coverage For The First Half of The SemesterJaneAinda não há avaliações

- 23 Republic v. Go PDFDocumento25 páginas23 Republic v. Go PDFClarinda Merle100% (1)

- IBP Ruling on Atty's DeceitDocumento7 páginasIBP Ruling on Atty's DeceitjwualferosAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Procedure Lecture Notes SummaryDocumento5 páginasCivil Procedure Lecture Notes SummaryDUN SAMMUEL LAURENTEAinda não há avaliações

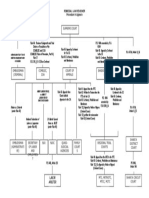

- Appeal Procedure FlowchartDocumento1 páginaAppeal Procedure FlowchartAaron ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Fria of 2010Documento55 páginasFria of 2010Alek SeighAinda não há avaliações

- Yu Con v. IpilDocumento4 páginasYu Con v. IpilMay ChanAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Law Case Digest: List of CasesDocumento57 páginasCommercial Law Case Digest: List of CasesJean Mary AutoAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Third DivisionDocumento55 páginasPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Third DivisionCams Tres ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Co V HRET 199 SCRA 692 FactsDocumento1 páginaCo V HRET 199 SCRA 692 FactsDenDen GauranaAinda não há avaliações

- PSE V CADocumento15 páginasPSE V CAMp CasAinda não há avaliações

- Cuison vs. Court of Appeals, 227 SCRA 391Documento12 páginasCuison vs. Court of Appeals, 227 SCRA 391KinitDelfinCelestialAinda não há avaliações

- CUISON VS CA G.R. No. 88539Documento3 páginasCUISON VS CA G.R. No. 88539encinajarianjayAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Motion to Vacate, Motion to Dismiss, Affidavits, Notice of Objection, and Notice of Intent to File ClaimNo EverandSample Motion to Vacate, Motion to Dismiss, Affidavits, Notice of Objection, and Notice of Intent to File ClaimNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (21)

- Prayer To Close A MeetingDocumento1 páginaPrayer To Close A MeetingEng Simon Peter NsoziAinda não há avaliações

- Del Castillo CasesDocumento1.318 páginasDel Castillo CasesJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Eo 292 Chapter 7Documento5 páginasEo 292 Chapter 7potrehakhemahmadkiAinda não há avaliações

- Must Read Cases Civil Law As of March 31, 2015Documento101 páginasMust Read Cases Civil Law As of March 31, 2015Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- LTFRB Rules On HearingsDocumento1 páginaLTFRB Rules On HearingsJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- 70 Ibp Vs Mayor AtienzaDocumento4 páginas70 Ibp Vs Mayor AtienzaJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- LTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureDocumento25 páginasLTFRB Revised Rules of Practice and ProcedureSJ San Juan100% (2)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 páginas6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- MARINA Circular No 2011-04 Revised Rules Temporary Utilization of Foreign Registered ShipsDocumento8 páginasMARINA Circular No 2011-04 Revised Rules Temporary Utilization of Foreign Registered ShipsarhielleAinda não há avaliações

- IRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActDocumento42 páginasIRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActIrene Balmes-LomibaoAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Ethics 2011 Bar Exam QuestionnaireDocumento12 páginasLegal Ethics 2011 Bar Exam QuestionnaireAlly Bernales100% (1)

- IRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActDocumento42 páginasIRR of RA 9295 2014 Amendments - Domestic Shipping Development ActIrene Balmes-LomibaoAinda não há avaliações

- Linton Commercial v. HerreraDocumento21 páginasLinton Commercial v. HerreraJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- San Mig V CADocumento6 páginasSan Mig V CAJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- 1.2.4. Phil Realty V Ley Construction2Documento48 páginas1.2.4. Phil Realty V Ley Construction2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- CenidoDocumento26 páginasCenidoJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- 1.2.5. FilInvest V Ngilay2Documento11 páginas1.2.5. FilInvest V Ngilay2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Pimentel v. ErmitaDocumento15 páginasPimentel v. ErmitaAKAinda não há avaliações

- 1.2.1. Yap V COA2Documento23 páginas1.2.1. Yap V COA2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Veloso v. Ca2Documento13 páginasVeloso v. Ca2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Terre V TerreDocumento5 páginasTerre V TerreJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Rural Bank of Bonbon v. Ca2Documento9 páginasRural Bank of Bonbon v. Ca2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Simon Vs CHRDocumento25 páginasSimon Vs CHRJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Green Valley v. Iac2Documento5 páginasGreen Valley v. Iac2Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Univ of San Carlos V CA PDFDocumento9 páginasUniv of San Carlos V CA PDFJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Santa RosaDocumento11 páginasSanta RosaJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- 444 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Angeles vs. Philippine National Railways (PNR)Documento11 páginas444 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Angeles vs. Philippine National Railways (PNR)Jennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- R.27. Perez V ToleteDocumento11 páginasR.27. Perez V ToleteJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- CenidoDocumento26 páginasCenidoJennilyn TugelidaAinda não há avaliações

- Cifra Club - Ed Sheeran - PhotographDocumento2 páginasCifra Club - Ed Sheeran - PhotographAnonymous 3g5b91qAinda não há avaliações

- Hijab Final For 3rd ReadingDocumento5 páginasHijab Final For 3rd ReadingErmelyn Jane CelindroAinda não há avaliações

- CasesDocumento14 páginasCasesKate SchuAinda não há avaliações

- 20101015121029lecture-7 - (Sem1!10!11) Feminism in MalaysiaDocumento42 páginas20101015121029lecture-7 - (Sem1!10!11) Feminism in Malaysiapeningla100% (1)

- TENSES Fill in VerbsDocumento2 páginasTENSES Fill in VerbsMayma Bkt100% (1)

- Gsis Vs Civil Service CommissionDocumento2 páginasGsis Vs Civil Service CommissionCristineAinda não há avaliações

- US v. Bonefish Holdings LLC, 4:19-cr-10006-JEM Information Charges (Albert Vorstman)Documento4 páginasUS v. Bonefish Holdings LLC, 4:19-cr-10006-JEM Information Charges (Albert Vorstman)jorgelrodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Dworkin, Right To RidiculeDocumento3 páginasDworkin, Right To RidiculeHelen BelmontAinda não há avaliações

- Teodoro Regava Vs SBDocumento4 páginasTeodoro Regava Vs SBRafael SoroAinda não há avaliações

- Joe Cocker - When The Night Comes ChordsDocumento2 páginasJoe Cocker - When The Night Comes ChordsAlan FordAinda não há avaliações

- Communism's Christian RootsDocumento8 páginasCommunism's Christian RootsElianMAinda não há avaliações

- Juvenile Final A1Documento14 páginasJuvenile Final A1ashita barveAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Rights EssayDocumento4 páginasCivil Rights Essayapi-270774958100% (1)

- Outlaw King' Review: Bloody Medieval Times and GutsDocumento3 páginasOutlaw King' Review: Bloody Medieval Times and GutsPaula AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Peaceful Settlement of DisputesDocumento12 páginasPeaceful Settlement of DisputesKavita Krishna MoortiAinda não há avaliações

- Reception and DinnerDocumento2 páginasReception and DinnerSunlight FoundationAinda não há avaliações

- RICS APC - M006 - Conflict AvoidanceDocumento24 páginasRICS APC - M006 - Conflict Avoidancebrene88100% (13)

- SampleDocumento64 páginasSampleJunliegh permisonAinda não há avaliações

- Dark Void (Official Prima Guide)Documento161 páginasDark Void (Official Prima Guide)mikel4carbajoAinda não há avaliações

- Social StudiesDocumento15 páginasSocial StudiesRobert AraujoAinda não há avaliações

- Reyes Vs RTCDocumento2 páginasReyes Vs RTCEunice IquinaAinda não há avaliações

- People v. DioknoDocumento16 páginasPeople v. DioknoFlo Payno100% (1)

- ADR - Interim MeasuresDocumento24 páginasADR - Interim MeasuresNitin SherwalAinda não há avaliações

- CBSE Class 10 History Question BankDocumento22 páginasCBSE Class 10 History Question BankbasgsrAinda não há avaliações

- Araw ng Kasambahay rights and obligationsDocumento3 páginasAraw ng Kasambahay rights and obligationsKara Russanne Dawang Alawas100% (1)

- Employer Contractor Claims ProcedureDocumento2 páginasEmployer Contractor Claims ProcedureNishant Singh100% (1)

- IJCRT1134867Documento6 páginasIJCRT1134867LalithaAinda não há avaliações

- Edi-Staffbuilders International Vs NLRCDocumento7 páginasEdi-Staffbuilders International Vs NLRCErvenUmaliAinda não há avaliações

- Special Proceedings Case DigestDocumento14 páginasSpecial Proceedings Case DigestDyan Corpuz-Suresca100% (1)

- Civil v Common: Legal Systems ComparisonDocumento3 páginasCivil v Common: Legal Systems ComparisonAlyk Tumayan CalionAinda não há avaliações