Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

050906A Nurse Led Approach To Diabetic Retinal Screening 2

Enviado por

anisarahma718Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

050906A Nurse Led Approach To Diabetic Retinal Screening 2

Enviado por

anisarahma718Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CLINICAL

development

A nurse-led approach to

diabetic retinal screening

Cummings, M. (2002) Screening for

diabetic retinopathy. Practical Diabetes

International; 19: 1, 5.

Department of Health and British

Diabetic Association (1995) St. Vincent

Joint Task Force for Diabetes (Visual

Impairment Subgroup).

London: DoH.

Department of Health (2003) National

Service Framework for Diabetes:

Delivery Strategy. London: DoH.

In industrialised countries diabetic retinopathy is

the leading cause of blindness in people under the

age of 60 (NICE, 2002). Ninety per cent of people

with type 1 diabetes have some degree of diabetic

retinopathy within 20 years of diagnosis and more

than 60 per cent of people with type 2 diabetes

will experience this complication (NICE, 2002). It

has been suggested that it is present at diagnosis

in 40 per cent of those with type 2 diabetes (Cummings, 2002). However, treatment can prevent

blindness in 90 per cent of those at risk if applied

early and adequately (DoH and BDA, 1995).

The delivery strategy for the National Service

Framework for Diabetes (DoH, 2003) has prioritised retinopathy screening in the UK as one of two

critical national targets. By 2006 a minimum of 80

per cent of people with diabetes should be offered

screening for the early detection and treatment of

diabetic retinopathy, rising to 100 per cent by the

end of 2007.

Diabetic retinopathy

Retinopathy is a vascular complication of diabetes

mellitus. The predisposing factors include:

l Hyperglycaemia;

l Hypertension;

l Hyperlipidaemia;

l Long duration diabetes;

l Genetic predisposition.

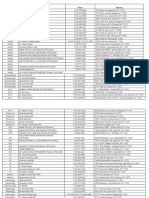

James et al (2003) have classified diabetic retinopathy according to the stage reached and presenting clinical features (Table 1).

At the Western Eye Hospital a nurse-led approach to diabetic retinal screening is well established and underpinned by an evidence-based

protocol (Table 2, p34). It is being undertaken by

32

senior ophthalmic practitioners as part of a weekly

clinic in the outpatient department. This service

was first established in 1998. A combination of

digital photography and slit-lamp biomicroscopy is

used to perform this procedure. Sharp et al (2003)

conclude that digital imaging is an effective method and has lower technical failure rates compared

with conventional photography. Patients are referred to the clinic from primary, secondary and

tertiary care services.

Presentation at clinic

On arrival at the clinic the patient is welcomed by

the nurse practitioner. Effective communication

skills are key in establishing good rapport, reducing anxiety and gaining the patients confidence

and cooperation prior to and during the procedure.

The sense of vision is often not fully appreciated

until it is compromised. Thus, impairment or potential impairment of vision can create feelings of

anxiety about blindness (Vafidis, 1997).

As part of the medical assessment, the blood

pressure is taken and details recorded on the questionnaire. As part of the ocular assessment, visual

acuity is recorded by the ophthalmic nurse for

medical and legal reasons. The visual acuity of

each eye is measured using Snellens Chart. If the

patient usually wears glasses, they should be worn

during the assessment to achieve the best visual

acuity possible. If the acuity is less than 6/12 and

the patient does not wear glasses, a pinhole will

be used to determine whether the decreased vision is due to a refractive error or pathological

changes in the retina, cornea, lens or vitreous. The

pinhole assists in determining the best visual acuity possible with a refractive correction. Any significant deterioration in vision will be noted.

The intraocular pressure (IOP) is measured and

the optic disc is examined. Dilatation of the pupils

is essential for retinal screening to provide a wider

and clearer view of the retina during the procedure. However, dilating drops are contraindicated

for a patient with relative afferent pupillary defect

(RAPD). This condition usually indicates some underlying optic nerve disorder. Therefore, it is essential that the nurse checks the pupils for direct

and consensual responses to light to exclude this

possibility of RAPD. The nurse can identify RAPD by

examining the patients eyes with a bright light in

a dimly illuminated room. Normally, when a light

NT 6 September 2005 Vol 101 No 36 www.nursingtimes.net

Alamy

References

Author Sue Watkinson, PhD, PGCEA, RGN, OND,

is senior lecturer in research, Faculty of Health

and Human Sciences, Thames Valley University,

London; Nandy Chetram, RN, ONC, is sister, outpatient department, Western Eye Hospital, London.

Abstract A nurse-led approach to diabetic

retinal screening. Nursing Times; 101: 36: 3234.

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in people under the age of 60 in industrialised countries (NICE, 2002). This article discusses

a nurse-led approach to diabetic retinal screening

currently being undertaken at the Western Eye

Hospital, London.

keywords n Diabetic retinopathy n Diabetic retinal screening n Nurse-led practice

Table 1. Classification of diabetic retinopathy (James et al, 2003)

References

Stage reached

Clinical features

No retinopathy

No abnormal retinal signs

Vision normal

James, B. et al (2003) Lecture Notes

on Ophthalmology. Oxford:

Blackwell Science.

Background (Figure 1)

Microvascular leakage of haemorrhages and exudates

away from the macula

Vision normal

Maculopathy (Figure 2)

Exudates and haemorrhages within the macular region

and/or evidence of retinal oedema and ischaemia

Vision may be reduced

Sight-threatening

Pre-proliferative

Vascular occlusion (cotton wool spots), irregular veins

Vision normal

Proliferative (Figure 3)

New vessel growth on optic disc or elsewhere on retina

Vision normal

Sight-threatening

Advanced

Bleeding into the vitreous or between the vitreous and

the retina

Possibility of retinal detachment

Vision reduced, often acutely with vitreous haemorrhage

Sight-threatening

is shone into one eye, both pupils constrict. When

a light is shone into the abnormal eye of a patient

with RAPD, the pupil of the affected eye dilates

rather than constricts. If a RAPD is detected, the

patient will be referred straightaway to the ophthalmologist for assessment and appropriate action.

Dilating drops will also be contraindicated for a

patient with a history of, or risk factors for, narrow

angle glaucoma since this may result in a sudden

increase of IOP. If the IOP is found to be too high,

then the patient will be referred to A&E or a glaucoma clinic for a clinical assessment by an ophthalmologist. It is useful to mention to the patient that

should the eyes become painful and the vision

much more blurred later in the day they should

return to the A&E department.

Tropicamide and phenylephrine eye drops are instilled to dilate the pupils. Before instilling these

Figure 1.

Background diabetic

retinopathy

National Institute for Clinical Excellence

(NICE) (2002) Management of Type 2

Diabetes Retinopathy: Early Management and Screening. Available at:

www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=27915

drops the patient should be informed that initially

this causes a stinging sensation. The ability of the

eyes to focus normally is impaired, causing blurred

vision and sensitivity to light for a few hours after

the procedure. Therefore, it will be difficult to read

properly and the patient should be advised for

health and safety reasons not to drive or operate

any machinery for a few hours afterwards, and to

wear dark glasses in bright light for more comfort.

The health education role

Health education as a preventative strategy is an

important aspect of the nurses role in the management of diabetic patients undergoing retinal

screening. It is therefore important to review the

patients diabetic control and to measure and

record the blood pressure. Primary and secondary

prevention of sight-threatening disease is the aim

Figure 2.

Maculopathy

NT 6 September 2005 Vol 101 No 36 www.nursingtimes.net

Lloyd, C. et al (1995) The progression of

retinopathy over 2 years: the Pittsburgh

Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications

(EDC) Study. Journal of Diabetes Complications; 9: 3, 140148.

Figure 3.

Proliferative

retinopathy

This article has been double-blind

peer-reviewed.

For related articles on this subject

and links to relevant websites see

www.nursingtimes.net

33

development

References

Sharp, P.F. et al (2003) The value of

digital imaging in diabetic retinopathy.

NHS R&D HTA Programme. Health

Technology Assessment; 7: 30, 3.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group

(1998) Tight blood pressure control and

risk of macrovascular and microvascular

complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS

38. British Medical Journal.

317: 7160, 703713.

Vafidis, J. (1997) Purchasing good

quality eye care; the providers view.

Quality in Health Care; 6: 2, 9298.

Walker, R., Rodgers, J. (2002) Diabetic

retinopathy. Nursing Standard;

16, 45, 4652.

Table 2. Protocol for diabetic retinal screening

Measure visual acuity using Snellens Chart

Dilate the pupils using mydriatic eye drops, except for patients with glaucoma

l Examine the lens, vitreous, macula, optic disc and the remainder of the retina to

monitor any changes

l Interpret the results of the retinal photographs and then provide an explanation to the patient

l Refer the patient promptly where laser therapy is indicated

l

l

of diabetic retinopathy care (Walker and Rodgers,

2002). As a health promoter, the nurses role is to

educate patients about diabetic retinopathy and

how it relates to their diabetes. Awareness should

be raised about the support and advice offered by

such organisations as Diabetes UK and the RNIB.

As a health educator, the nurse should also provide patients and families with reliable evidence

and advice about the importance of maintaining

good glucose and blood pressure control. Good

blood glucose control means maintaining levels at

below HbA1c 6.57.5 per cent, dependent on the

individuals risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications (NICE, 2002). An increased severity of diabetic retinopathy is associated with poorer

blood glucose control (Lloyd et al, 1995).

However, it is also important to help people understand that the temporary blurring of vision that

can occur with hyperglycaemia is not retinopathy,

but rather osmotic changes in the lens that cause

focusing problems (Walker and Rodgers, 2002).

Other factors such as presbyopia (age-related

blurred near vision) and cataract (opacity of the

lens) may also cause blurring of vision.

Maintaining good blood pressure control is also

important and an ideal is at or below 140/80mmHg

(NICE, 2002). Blood pressure control in people with

type 2 diabetes is associated with a decreased risk

of retinopathy progression (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998). Health education should

include the best available research evidence to

empower patients to make decisions about lifestyle changes and gain control over their condition.

The procedure

The patient is escorted by the ophthalmic nurse and

positioned appropriately and as comfortably as possible at the slit-lamp to face the retinal camera. A

brief explanation of the procedure is given again as

the patients cooperation during the process is key

to securing quality digital images of the retina.

The patient is asked not to blink during the photography and to fixate on a green light when looking at the retinal camera. This maximises the clarity of the retinal images. Photographs are taken of

the optic disc and the macula in each eye. This

takes 2025 seconds. Two colour photographs are

taken of each eye.

34

Grading is the next stage undertaken in this process. This involves grading the photographs to determine whether any diabetic retinopathy is present

and, if so, to assess the stage reached. Grading also

involves examining the lens, vitreous, optic disc

and the remainder of the retina. The senior ophthalmic nurse will shortly become responsible for

this stage. Currently, however, it is performed by an

associate specialist in the diabetic clinic.

After the procedure

For those patients in the early stage of diabetic

retinopathy laser therapy is given to preserve the

remaining level of sight. It is important to explain

to the patient that this treatment will not restore

sight already lost. These patients will also be encouraged to achieve the best possible diabetic control in order to increase the likelihood of preserving their vision in the longer term.

Patients with no retinopathy or with mild background changes are given an appointment for a

re-examination every 12 months. Those patients

with a deteriorating background retinopathy will

be examined every six months.

Importantly, depending on the stage of the diabetic retinopathy and the degree of visual loss,

advice is given about the services provided by the

RNIB in helping and supporting patients to manage visual impairment.

Patients are also advised to visit their optician

annually. Appropriate referral to members of the

multidisciplinary team such as the social worker

should also be made in order to ensure that ongoing needs are met.

Conclusion

The scope of clinical practice for senior ophthalmic

nurse practitioners in the outpatient department

has been extended by enabling them to undertake

diabetic retinal screening for patients with diabetes. They have increased their knowledge of diabetes and diabetic eye disease and have enhanced

their technical skills. Consequently, they are delivering quality care underpinned by an evidencebased approach to health education. They are also

using technical equipment to perform retinal

screening procedures such as slit-lamp biomicroscopy and digital photography. n

NT 6 September 2005 Vol 101 No 36 www.nursingtimes.net

Você também pode gostar

- Diabetic RetinopathyDocumento13 páginasDiabetic RetinopathyjaysonAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy: Introduction to Novel Treatment StrategiesNo EverandDiabetic Retinopathy: Introduction to Novel Treatment StrategiesAinda não há avaliações

- Current Management of Diabetic MaculopathyDocumento8 páginasCurrent Management of Diabetic MaculopathyraniAinda não há avaliações

- Early Photocoagulation For Diabetic Retinopathy: ETDRS Report Number 9Documento20 páginasEarly Photocoagulation For Diabetic Retinopathy: ETDRS Report Number 9Bernardo RomeroAinda não há avaliações

- Visual Dysfunction in DiabetesDocumento395 páginasVisual Dysfunction in DiabetesSergioAcuñaAinda não há avaliações

- AteroscleroticDocumento5 páginasAteroscleroticPutri PurnamaAinda não há avaliações

- BPJ 30 Retinopathy Pages38-50Documento13 páginasBPJ 30 Retinopathy Pages38-50DeboraNainggolanAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of Ocular Manifestations in Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocumento5 páginasEvaluation of Ocular Manifestations in Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDona Parenta NantaliaAinda não há avaliações

- CLinical Audit On Diabetic Retinopathy EyeDocumento49 páginasCLinical Audit On Diabetic Retinopathy EyeZiaul HaqueAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy: Merican Iabetes SsociationDocumento4 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy: Merican Iabetes SsociationMuhammad Wahyu SetianiAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic RetinopathyDocumento4 páginasDiabetic RetinopathybencleeseAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy - Endotext - NCBI BookshelfDocumento24 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy - Endotext - NCBI BookshelfANDREW OMAKAAinda não há avaliações

- Fundus Camera As A Screening For Diabetic Retinopathy in AMC Yogyakarta IndonesiaDocumento7 páginasFundus Camera As A Screening For Diabetic Retinopathy in AMC Yogyakarta IndonesiaAgusAchmadSusiloAinda não há avaliações

- PJMS 32 1229Documento5 páginasPJMS 32 1229Nurvita WidyastutiAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines 4 Diabetes FinalDocumento3 páginasGuidelines 4 Diabetes FinaleyepageAinda não há avaliações

- Retinopatia NeuropatiaDocumento13 páginasRetinopatia NeuropatiaFrancisca Gamonal ArenasAinda não há avaliações

- Risk Factors and Incidence of Macular Edema After Cataract SurgeryDocumento10 páginasRisk Factors and Incidence of Macular Edema After Cataract SurgeryAnonymous eF8cmVvJaAinda não há avaliações

- Studies On Diab RetinoDocumento12 páginasStudies On Diab RetinoShankar ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- HistoryDocumento9 páginasHistoryRara Aulia IIAinda não há avaliações

- LimitedDocumento2 páginasLimitedlfathiyahAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy Detection Using Image Processing (GUI)Documento9 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy Detection Using Image Processing (GUI)koushikAinda não há avaliações

- Predictive Factors of Visual Outcome of Malaysian Cataract Patients: A Retrospective StudyDocumento8 páginasPredictive Factors of Visual Outcome of Malaysian Cataract Patients: A Retrospective Studyanita adrianiAinda não há avaliações

- ETDRSDocumento16 páginasETDRSAna Cecy AvalosAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy: Clinical Findings and Management: Review ArticleDocumento4 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy: Clinical Findings and Management: Review ArticlewadejackAinda não há avaliações

- Glaukoma Case ReportDocumento9 páginasGlaukoma Case ReportHIstoryAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Macular EdemaDocumento48 páginasTreatment of Macular EdemaPushpanjali RamtekeAinda não há avaliações

- Social Approach To Diabetic Retinopathy in NigeriaDocumento14 páginasSocial Approach To Diabetic Retinopathy in NigeriaEmmanuel OgochukwuAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy: From Diagnosis to TreatmentNo EverandDiabetic Retinopathy: From Diagnosis to TreatmentNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (3)

- Visual Dysfunction in Diabetes PDFDocumento395 páginasVisual Dysfunction in Diabetes PDFMarcosAinda não há avaliações

- Risk factors of diabetic retinopathy and vision threatening diabetic retinopathy and vision threatening diabetic retinopaty based on diabetic retinopathy screening program in greater bandung, west java.astriDocumento14 páginasRisk factors of diabetic retinopathy and vision threatening diabetic retinopathy and vision threatening diabetic retinopaty based on diabetic retinopathy screening program in greater bandung, west java.astriSi PuputAinda não há avaliações

- Commentary: The Optic Neuritis Treatment TrialDocumento2 páginasCommentary: The Optic Neuritis Treatment TrialEmmanuel Zótico Orellana JiménezAinda não há avaliações

- Advances in The Management of Diabetic Macular Oedema Based On Evidence From The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research NetworkDocumento11 páginasAdvances in The Management of Diabetic Macular Oedema Based On Evidence From The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research NetworkNatalia LeeAinda não há avaliações

- A Review of Optic NeuritisDocumento5 páginasA Review of Optic NeuritissatrianiAinda não há avaliações

- Multi-Stage Segmentation of The Fovea in Retinal Fundus Images Using Fully Convolutional Neural NetworksDocumento18 páginasMulti-Stage Segmentation of The Fovea in Retinal Fundus Images Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networksyt HehkkeAinda não há avaliações

- A Practical Manual of Diabetic Retinopathy ManagementNo EverandA Practical Manual of Diabetic Retinopathy ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- Deep Learing Technique For Diabetic Retinopath ClassificationDocumento10 páginasDeep Learing Technique For Diabetic Retinopath ClassificationIJRASETPublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy Image Database (Dridb) : A New Database For Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programs ResearchDocumento6 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy Image Database (Dridb) : A New Database For Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Programs ResearchCakra KartaAinda não há avaliações

- Practice: Diabetic RetinopathyDocumento1 páginaPractice: Diabetic RetinopathyRina ChairunnisaAinda não há avaliações

- DR ReportDocumento21 páginasDR ReportSahil NegiAinda não há avaliações

- Retina 39 426Documento9 páginasRetina 39 426ryaalwiAinda não há avaliações

- The Columbia Guide to Basic Elements of Eye Care: A Manual for Healthcare ProfessionalsNo EverandThe Columbia Guide to Basic Elements of Eye Care: A Manual for Healthcare ProfessionalsDaniel S. CasperAinda não há avaliações

- RCollOph Guidelines For DRDocumento14 páginasRCollOph Guidelines For DRdrvishalkulkarni2007Ainda não há avaliações

- Predictors For Diabetic Retinopathy in Normoalbuminuric People With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocumento6 páginasPredictors For Diabetic Retinopathy in Normoalbuminuric People With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusdrheriAinda não há avaliações

- Vukicevic Et Al 2021 Wfksizpmfaet PDFDocumento5 páginasVukicevic Et Al 2021 Wfksizpmfaet PDFMeri VukicevicAinda não há avaliações

- Retinopatía, Neuropatía y Pie DiabeticoDocumento13 páginasRetinopatía, Neuropatía y Pie DiabeticoAna CaballeroAinda não há avaliações

- USMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Surgery, Epidemiology/Biostatistics, Patient SafetyNo EverandUSMLE Step 3 Lecture Notes 2021-2022: Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Surgery, Epidemiology/Biostatistics, Patient SafetyNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- DM Dan GlaukomaDocumento5 páginasDM Dan GlaukomaYandhie RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis and Management of Ocular Manifestation in Diabetic Patients - Dr. Dr. Nadia Artha Dewi, SPM (K)Documento25 páginasDiagnosis and Management of Ocular Manifestation in Diabetic Patients - Dr. Dr. Nadia Artha Dewi, SPM (K)mbah gugelAinda não há avaliações

- Demographic and Clinical Profile of Patients Who Underwent Refractive Surgery ScreeningDocumento8 páginasDemographic and Clinical Profile of Patients Who Underwent Refractive Surgery ScreeningPierre A. RodulfoAinda não há avaliações

- Vitrectomy Results in Proliferative Diabetic RetinopathyDocumento3 páginasVitrectomy Results in Proliferative Diabetic RetinopathyRohamonangan TheresiaAinda não há avaliações

- BMC OphthalmologyDocumento7 páginasBMC OphthalmologyRizki Yuniar WAinda não há avaliações

- Vashits 2011Documento6 páginasVashits 2011gusnanto luthfiAinda não há avaliações

- Tham 2020 Oi 200342Documento10 páginasTham 2020 Oi 200342Oscar Julian Perdomo CharryAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing The Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report Number 10Documento2 páginasAssessing The Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report Number 10Vivi DeviyanaAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Acute Anterior Uveitis in The Community As Seen in An Emergency Eye Centre. A Lesson For The General PractitionerDocumento5 páginasTreatment of Acute Anterior Uveitis in The Community As Seen in An Emergency Eye Centre. A Lesson For The General Practitioneralfahrimaulana85Ainda não há avaliações

- Sum - Clinical DR and DMEDocumento2 páginasSum - Clinical DR and DMEsolihaAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Retinopathy: Merican Iabetes SsociationDocumento4 páginasDiabetic Retinopathy: Merican Iabetes SsociationmodywbassAinda não há avaliações

- Combined Intravitreal Ranibizumab and Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy Versus Ranibizumab Alone For The Treatment of Age-Related Macular DegenerationDocumento5 páginasCombined Intravitreal Ranibizumab and Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy Versus Ranibizumab Alone For The Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration568563Ainda não há avaliações

- 14 AdaDocumento13 páginas14 Adaic.guadalajara.ayalaAinda não há avaliações

- Rekap Data Kehadiran Okt 23Documento5 páginasRekap Data Kehadiran Okt 23anisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- 2016 Undergraduate Academic ScheduleDocumento4 páginas2016 Undergraduate Academic Scheduleanisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- 25 OS OD: Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy in The Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine StudyDocumento2 páginas25 OS OD: Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy in The Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine Studyanisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- Reference 5Documento4 páginasReference 5anisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- Scabies GuidelineJanuary 2013Documento13 páginasScabies GuidelineJanuary 2013anisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis and New Treatments in Muscular Dystrophies: Doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158329Documento4 páginasDiagnosis and New Treatments in Muscular Dystrophies: Doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.158329anisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- Personal HygieneDocumento2 páginasPersonal Hygieneanisarahma718Ainda não há avaliações

- Contusio BulbiDocumento2 páginasContusio BulbiSuzan LaiAinda não há avaliações

- Christopher D. Moyes, Patricia M. Schulte - Principles of Animal Physiology-Pearson (2016)Documento775 páginasChristopher D. Moyes, Patricia M. Schulte - Principles of Animal Physiology-Pearson (2016)salvatore.sara323Ainda não há avaliações

- Name Module No: - 8 - Module Title: Learners With Difficulty Seeing Course and Section: BSED-3A - Major: Social ScienceDocumento6 páginasName Module No: - 8 - Module Title: Learners With Difficulty Seeing Course and Section: BSED-3A - Major: Social ScienceChristine Joy MarcelAinda não há avaliações

- RefraksiDocumento84 páginasRefraksinaroetocapkutilAinda não há avaliações

- Case KatarakDocumento8 páginasCase KatarakLatoya ShopAinda não há avaliações

- CBSE Class 10 English Lang and Lit Paper 2019Documento39 páginasCBSE Class 10 English Lang and Lit Paper 2019Pratapsamrat SinghAinda não há avaliações

- A Brief History of Science, Thomas CrumbDocumento467 páginasA Brief History of Science, Thomas Crumbenescampos100% (1)

- Care of The EyeDocumento3 páginasCare of The EyeJerryDelgadoGuillermoAinda não há avaliações

- Ophtha Quiz - Optics and RefractionDocumento2 páginasOphtha Quiz - Optics and Refractionadi100% (1)

- Behind The LensDocumento3 páginasBehind The Lensapi-427418182Ainda não há avaliações

- Health AssessmentDocumento160 páginasHealth AssessmentJerome TingAinda não há avaliações

- Field of SpecialistDocumento4 páginasField of Specialistapi-598083311Ainda não há avaliações

- Special SensesDocumento24 páginasSpecial SensesKaye Valenzuela0% (1)

- Power of Images, Images of Power in Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-FourDocumento18 páginasPower of Images, Images of Power in Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-FourAseel IbrahimAinda não há avaliações

- Asvs 04 0267Documento7 páginasAsvs 04 0267T KAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 Catalog Rev 2Documento43 páginas2018 Catalog Rev 2German BarcenasAinda não há avaliações

- Product Brochure 211023 PDFDocumento34 páginasProduct Brochure 211023 PDFIsha Eye HospitalAinda não há avaliações

- NSSBIO3E Chapter Test Ch15 eDocumento17 páginasNSSBIO3E Chapter Test Ch15 e托普斯Ainda não há avaliações

- Anisman Acute Vision LossDocumento68 páginasAnisman Acute Vision Lossarnol3090Ainda não há avaliações

- Visual Acuity Form-6Documento1 páginaVisual Acuity Form-6MN VenkatesanAinda não há avaliações

- CBSE Class 8 Science Paper 1 2014Documento4 páginasCBSE Class 8 Science Paper 1 2014Anurag SaikiaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of Computer Science Research - Vol.4, Iss.1 January 2022Documento58 páginasJournal of Computer Science Research - Vol.4, Iss.1 January 2022Bilingual PublishingAinda não há avaliações

- Bilateral Using MusicDocumento11 páginasBilateral Using Musicmuitasorte9Ainda não há avaliações

- Anatomy of The Eye PDFDocumento15 páginasAnatomy of The Eye PDFPaolo Naguit0% (1)

- Explain About Elements of Visual PerceptionDocumento8 páginasExplain About Elements of Visual PerceptionYagneshAinda não há avaliações

- Optomap Af Diagnostic AtlasDocumento36 páginasOptomap Af Diagnostic AtlasanamariaboariuAinda não há avaliações

- Full Download Economics Principles Problems and Policies Mcconnell 20th Edition Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocumento36 páginasFull Download Economics Principles Problems and Policies Mcconnell 20th Edition Test Bank PDF Full Chapteruncanny.tigereye.zi0uv100% (18)

- SpiderDocumento27 páginasSpiderCharles LeRoyAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Sciences: Instructions For CandidatesDocumento9 páginasClinical Sciences: Instructions For CandidatesHussain SyedAinda não há avaliações

- The Bird by Colin Tudge - ExcerptDocumento42 páginasThe Bird by Colin Tudge - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group18% (28)