Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Complications of Chronic Use of Skin Lightening Cosmetics PDF

Enviado por

Ichsan IrwantoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Complications of Chronic Use of Skin Lightening Cosmetics PDF

Enviado por

Ichsan IrwantoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Report

Oxford, UK

International

IJD

Blackwell

0011-9059

XXX

Publishing

Journal Ltd,

Ltd

of Dermatology

2007

Complications of chronic use of skin lightening cosmetics

Complications

Olumide

Case

report

et al. of skin lightening cosmetics

Yetunde M. Olumide, MD, Ayesha O. Akinkugbe, MD, Dan Altraide, MD, Tahir Mohammed,

MD, Ngozi Ahamefule, MD, Shola Ayanlowo, MD, Chinwe Onyekonwu, MD,

and Nyomudim Essen, MD

From the Dermatology Unit, epartment of

Medicine, College of Medicine, Lagos, Nigeria

Correspondence

Y. Mercy Olumide

Department of Medicine

College of Medicine of the University of Lagos

P M B 12003, Lagos, Nigeria

E-mail: mercyolumide2004@yahoo.co.uk

Abstract

Skin lightening (bleaching) cosmetics and toiletries are widely used in most African countries.

The active ingredients in these cosmetic products are hydroquinone, mercury and

corticosteroids. Several additives (conconctions) are used to enhance the bleaching effect.

Since these products are used for long duration, on a large body surface area, and under hot

humid conditions, percutaneous absorption is enhanced. The complications of these products

are very serious and are sometimes fatal. Some of these complications are exogenous

ochronosis, impaired wound healing and wound dehiscence, the fish odor syndrome,

nephropathy, steroid addiction syndrome, predisposition to infections, a broad spectrum of

cutaneous and endocrinologic complications of corticosteroids, including suppression of

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In this era of easy travels and migration, African patients

with these complications can present to physicians anywhere in the world. It is therefore critical

for every practicing physician to be aware of these complications.

A middle-aged Nigerian lady was recently brought home to

die from a Western European country because she developed an

uncontrollable diabetes mellitus and evidence of hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis suppression. On clinical examination,

the lady had dense stigmatas of chronic use of skin lightening

creams, which was confirmed through history. Majority of

medical practitioners outside subsaharan Africa may not be

familiar with this habit of bleaching the skin nor the cutaneous

and extra-cutaneous complications of this widespread

cosmetic habit of black Africans. Furthermore, these cosmetics

and toiletries are not sold in the regular departmental stores nor

pharmacy shops in Europe and North America. They are either

manufactured purely for export to Africa or are exported

from Africa to Europe and N. America so that they are sold only

in local shops in ghettos patronized by the black Africans.

This paper sets out to give a brief review of this problem so

that practitioners worldwide would be aware of these complications which may at times be fatal.

Literature review

344

The use of skin bleaching agents or lighteners has been

reported in many parts of the world, such as Kenya,1 Ghana2

South Africa3,4 Zimbabwe5 USA6,7 Great Britain8 and SaudiArabia.9 Various chemicals have been used with consequent

undesirable side-effects. While phenols were reported to have

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

been associated with ochronosis10 the mercurials were

implicated in nephropathy.1,9 Addo in Ghana has also

reported squamous cell carcinoma associated with prolonged

bleaching.11

A survey done in Mali reported that 25% of two hundred

and ten women developed 74 different side-effects from the

use of bleaching creams.12 Similarly, in a refugee camp in

Balkan, 22.3% of the inhabitants including children were

found to have high concentrations of urinary mercury, which

was traced to the use of mercury containing bleaching

ointments, supplied.13

Exogenous ochronosis was first reported in 1906.14 It

commonly presents as asymptomatic blue-black macules on

the malar areas, temples, inferior cheeks and neck.15 This

condition resembles endogenous ochronosis in the skin

histologically, but does not exhibit any systemic complications

or the urinary abnormality. Hydroquinones are by far the

most common offending agents, but phenol, quinine injection

and resorcinol have also been implicated.16

In South Africa, where the first reports of complications of

hydroquinone abuse was reported, the government was prevailed upon in 1980 to set an upper limit of 2% hydroquinone

content in cosmetic products.17 Britain and the United States

of America also limit the concentration of hydroquinone in

cosmetic products to a maximum of 2%, and in dermatological

preparations to 4%. Although it was originally believed that

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Olumide et al.

only high concentrations of hydroquinone were causal there

have been reports of ochronosis after use of 2% hydroquinone

preparations.1820 It has also been suggested that the percentage

of hydroquinone quoted by a manufacturer may not represent

the true concentration of hydroquinone in a product.21 It may

be that it is not the high concentration of hydroquinone, but

rather, extended use of this substance, which causes the

disease. An analysis of 41 bleaching creams available over the

counter in the UK in 1986 by Boyle and Kennedy revealed

that eight contained more than 2% hydroquinone.22

The scenario in Nigeria2333

The use of skin lightening creams has become a serious

phenomenon widely practiced by both men and women in

Nigeria. In a study of four hundred and fifty Nigerians who

confessed the use of bleaching creams, 73.3% were women

and 27.6% were men. The use of bleaching creams cuts

across all sociodemographic characteristics. People of all

religious groups, single or married, rich and poor, literate and

illiterate, low, middle and upper class use the products.

Various reasons were given for using the products. Some of

these are to look more attractive; to go with existing fashion

trend; to treat skin blemishes like acne or melasma; to cleanse

or tone the face and body; or to satisfy the taste of ones spouse.

Although the men also use the products for the above reasons,

some of them claimed they use the creams because their wives

use them; and some male marketers of female cosmetics and

toiletries claim they use the products to advertise their wares.

Some of the men are homosexuals. The habit of bleaching the

skin is most rampant among commercial sex workers who

camouflage their occupation in the clinic data as fashion

designer because of the opprobium attached to prostitution.

It is noteworthy that even some people who are naturally fair

in complexion, still use the bleaching creams to maintain the

light skin color and prevent tanning or blotches from sunlight.

As a result of both medical and public outcry against the

damaging effects of the skin lightening creams, the National

Food and Drug Agency of Nigeria (NAFDAC) had initially

allowed a maximum of 2% hydroquinone in bleaching

creams. However, due to the adverse side-effects associated

with long-term hydroquinone use and also lack of compliance

with content and labeling requirements, all forms of bleaching

agents were prohibited in cosmetics and toiletries. However,

in spite of the ban on these products, both the importation

and manufacture of the products have continued unabated.

This situation has been fostered largely by the vulnerability

of the consumers, the inexpensive nature of some of these

products, and the advertising agencies, who use lightcomplexioned ladies to advertise most consumer products

(e.g. alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages, toiletries, cosmetics,

textiles, telephone handsets, etc.) both on the electronic and

print media. Hence, the dominant signal being sent to an

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Complications of skin lightening cosmetics Report

undiscerning mind is that light complexioned people are

the beautiful ones.

In regard to ingredient labeling of cosmetics and toiletries

in Nigeria, most products are not registered by NAFDAC,

and bear no ingredient labeling nor address of manufacturers.

Some are even misbranded, e.g. a product which was labeled

as Betnovate-N was found to contain Mercury. Furthermore, the concentrations of chemicals on the labeled

products were largely found to be inaccurate on analysis as

most products exceeded the concentrations displayed on the

products. Since hydroquinone and mercury in cosmetics and

toiletries have been prohibited and have gained some notoriety,

manufacturers have now resorted to using synonyms of

hydroquinone to camouflage the products. Some of these

synonyms include 1, 4-Benzenediol, Quinol, Benzene-1,

4-diol, p-Diphenol, p-Dihydroxyl benzene, Hydrochinone,

p-hydroxylphenol, Hydrochinonium, Hydroquinol, and

Tequinol. All corticosteroid preparations can be purchased

over-the-counter in Nigeria. Hence, these products are readily

available not only in the pharmacy shops but also among

drug vendors in the open market place.

Chemicals often used and methods of use

The list of some of the bleaching creams used are given in

Table 1, and the contents of some analyzed products are on

Table 2. The same products are largely available in the African

countries mentioned above because of easy cross country

trade links. The active ingredients commonly used are hydroquinone, mercury, and a broad spectrum of the very potent

Table 1 A list of some of the bleaching creams used by patients

in Nigeria and ingredients as labeled

Cream

Ingredients

Movate

Crusader

Looking Good

Peauclair

Mic

Tura

Betamethasone dipropionate

Vitamed B3 toner 2%, Escalol UV 507, Vit E Allantoin

2% hydroquinone, Allantoin, Sunscreen, Vit E

Hydroquinone, Clobetasol propionate

Hydroquinone, Dimethicone, D-methyl-PABA

Octyl-Dimethyl PABA, Dimethicone,

Aqua glyceryl, propylene glycol mubbery

A-hydroxyl acids, methyl p-ben

Vitamed B3 toner 2%, Escalol UV 507, Vit E Allantoin

Benzophone 3-Dimethicone, Cyclomethicone

Triethanolamine, Carbomer, Dimethicone

Betamethasone dipropionate

Triethanolamine

Natural Essences from botany

2% hydroquinone padimate

2% hydroquinone Octisalate

2% hydroquinone, Vit E 1.0

Clobetasol propionate 0.05

Stearic Acid, MPG, Sorbitol Jelly, Fragrance

A3

Ultra

Venus

Swiss collagen

Fashion Fair

IKB

Shirley

Ambi

Skin Success

Sivoclaire

Fashoin Fair

Tony Montana

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

345

346

Report Complications of skin lightening cosmetics

Olumide et al.

25

Table 2 Contents of some creams analyzed

Cream

Hydroquinone (mg%)

Mercury (mg/kg)

Looking Good

Movate

Crusader

Sivoclaire

Peauclaire

Mercury

Mic

Tura

A3

1.36

5.10

3.45

0.06

0.06

1.68

0.06

1.45

0.42

0.17

0.20

0.26

0.22

0.21

0.82

0.22

0.23

0.18

corticosteroid preparations containing, e.g. Betamethasone

valerate and Clobetasol propionate.

Furthermore, the products are hardly used as marketed and

various additives are used to enhance the bleaching effect.

Some of the additives (concoction) are lemon juice, potash,

tooth paste, liquid milk, pulverized Naphthalene (camphor)

balls a mothproofing agent, Vitamin C, peroxides and

chlorates used in hair dyes. At times detergents are added to the

concoction. Some of the creams have equivalent soaps with

same chemicals incorporated. Indeed, the above listed additives

are not exhaustive.

At the initiation of the bleaching habit, a total body surface

immersion bath is often used for maximum effect. The

bleaching is then maintained with daily applications of the

creams. Most of the creams are very cheap so it is possible to

spend as little as 2 US dollars (about 300 Nigerian Naira) a

month on the bleaching creams to maintain the light complexion. Continuous use of the chemical is mandatory so that

the skin does not repigment. Even when the complications

appear, the bleachers often intensify the use of the chemicals

with the hope that the skin complications would eventually

be bleached away. Multiple products containing different

chemicals may be used concurrently or sequentially.

The duration of use of the bleaching creams before the

onset of complications vary from 6 to 60 months. However,

history from patients is often inaccurate, and some even deny

use of the bleaching creams, or pretend not to know their

functions due to a guilt complex, because various religious

groups and the press continue to condemn the practice of

changing the color of the natural skin.

Pathogenesis and complications

Hydroquinone

Hydroquinone is a dihydric phenol that has two important

derivatives viz monobenzyl and monomethyl ether of hydroquinone. Hydroquinone is known to competitively inhibit

melanin production by inhibiting sulfhydryl groups and acting

as a substrate for tyrosinase. The melanosomes and ultimately

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

the melanocytes are damaged by semiquinone free radicals

released during the above reaction.3436

With prolonged application and sun stimulation, the

melanocytes recover from the damaging effect of the hydroquinone which passes down into the papillary dermis of the

skin. Hence they are actively taken up by fibroblasts and lead

to altered elastic fiber production and excretion of abnormal

material into new fiber bundles.37 Furthermore, benzoquinone

acetic acid formed during the oxidative processes in which

hydroquinone is involved, bind and cross link collagen fibers

leading to degenerative changes due to altered physico-chemical

bonds.

Histologic examination of exogenous ochronotic lesions

reveals yellow-brown banana-shaped fibers in the papillary

dermis. Homogenization and swelling of the collagen bundles

is noted and a moderate histiocytic infiltrate may be present.

Sarcoid-like granulomas with multinucleated giant cells

engulfing ochronotic particles have been noted.38 Transfollicular

elimination of ochronotic fibers has also been described.39

Fibers stain black with Fontana stain and blue-black with

methylene blue stain.18,40 Ultrastructural examination reveals

homogenous electron-dense, irregular structures embedded

in an amorphous granular material infiltrating adjacent

collagen fibril bundles.42,43 The source of these ochronotic

fibers is not clear. Topical hydroquinones may inhibit

homogentisic acid oxidase in the skin, resulting in the local

accumulation of homogentisic acid that then polymerizes to

form ochronotic pigment.37,44,45 Pigmented particles may be

elastic or collagen fibers.19,46 Melanocytes may be involved;

most cases involve sun-exposed sites and one case is reported

of ochronosis that avoided areas of vitiligo.19,47 The changes

in the collagen bundles may be responsible for the loss of

elasticity and poor wound healing.

Complications of hydroquinone use that have been

reported are dermatitis, exogenous ochronosis, cataract,

pigmented colloid milia, scleral and nail pigmentation and

patchy depigmentation.3,4,15,20,26 The pigmented exogenous

ochronotic lesions are most marked on sun-exposed areas of

the body namely, face, upper chest and upper back. Dogliotte48

described 3 stages of this condition: (1) Erythema and mild

pigmentation; (2) hyperpigmentation, black colloid milia and

scanty atrophy; and (3) papulonodules with or without

surrounding inflammation. Figures 13 show exogenous

ochronosis. Since most commercial sex workers use these skin

lightening creams, some of them are HIV positive; and in an

attempt to bleach away the pruritic papular eruption (PPE)

commonly seen in HIV/AIDS patients, the skin of the extremities appear scruffy with the excoriated papules on a

background of ochronotic pigmentation on bleached skin as

shown in Figs 4 and 5. A patient developed squamous cell

carcinoma on the site of chronic exogenous ochronosis

(Fig. 6). It is not clear if this is a chance finding or an expected

sequelae of hydroquinone induced exogenous ochronosis

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Olumide et al.

Complications of skin lightening cosmetics Report

Figure 1 Exogenous ochronosis (EO)

with superimposed chronic sun damage on the vulnerable

skin. Coalescence of multiple colloid milia may give rise to big

nodular lesions particularly on the upper back. The fawn

colored pigmentation of all 20 nails may mimic the yellow

nail syndrome hence the authors call the phenomenon

pseudo yellownail syndrome. Abnormal repigmentation

of depigmented skin has also been reported on discontinuing

therapy. This abnormal repigmentation has been attributed

to the Meirowsky effect of long wavelengths of ultraviolet

light darkening melanin already present in the skin and leading

to a skin color darker than that prior to bleaching. Because of

this repigmentation, users find it compelling to continue to

use the bleaching creams to maintain the newly acquired light

colored skin. Hence, the inevitable complications from

prolonged use. A more serious complication is loss of elasticity

of the skin and impaired wound healing. When cutting

through the skin, either for incisional biopsy or other surgical

procedures, it is as if one was cutting through the skin of a

cadaver. There is difficulty in apposing the edges of the

wounds when stitching, hence the skin often tears through the

suture material. Furthermore, there is often delayed wound

healing. After major abdominal surgeries like Caesarian

section, myomectomy, hysterectomy, etc., there may be

catastrophic wound dehiscence, burst abdomen, and death

from overwhelming infection.

The chronic bleachers also exude an offensive fish odor in

the sweat like the fish odor syndrome.39,40 The fish odor

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Figure 2 Exogenous ochronosis in man

Figure 3 Exogenous ochronosis (EO)

syndrome, also known as trimethylaminuria, is characterized

by body odor of rotten fish. This is due to excretion of a

chemical, trimethylamine in the breath, urine, sweat, saliva,

and vaginal secretions.41

Trimethylamine (TMA) is produced in the gut mainly by

bacterial degradation of choline and lecithin-rich foods, such

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

347

348

Report Complications of skin lightening cosmetics

Olumide et al.

Figure 6 Squamous cell epithelioma on exogenous ochronosis

Figure 4 Exogenous ochronosis in a patient with PPE

Figure 5 Exogenous ochronosis in a patient with PPE

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

as salt water fish, eggs, offals (such as intestines, liver, and

kidney), and leguminous vegetables such as soya beans.

Normally, this compound is converted by TMA oxidase into

a stable nonodorous trimethylamine N-oxide (TMA-oxide)

that is then excreted in the urine. In the presence of a defective

TMA oxidase activity, the accumulated TMA is eliminated as

a volatile product in the urine, sweat, and breath, giving the

affected individual the characteristic fishy smell.

The TMA oxidase activity may be defective because of a

congenital, inherited impairment of N-oxidation (primary

trimethylaminuria) or for other acquired reasons that

interfere with the action of the enzyme (secondary trimethylaminurias). Some of these causes are: (1) overload with

TMA precursors, such as choline and lecithin, leading to

the formation of an increased burden of TMA through

enterobacterial degradation; (2) intake of inhibitors of

TMA oxidase, both dietary (e.g. Brussels sprouts) and

pharmacologic (e.g. thiourea), and (3) liver and kidney

diseases. In all these cases, the causative agent may act

rather as an inducing, precipitating factor in predisposed

subjects, who are carriers of the potential defect as heterozygotes. Other causes of fish odor are bacterial vaginosis, and

pemphigus vulgaris or foliaceus due to muco-cutaneous

bacterial degradation of body fluids.

Hydroquinone is an antioxidant, it may cause the fish odor

by reducing the ability to oxidize trimethylamine in chronic

bleachers, or hydroquinone may act rather as an inducing,

precipitating factor in predisposed subjects, who are carriers

of the potential defect as heterozygotes.

Treatment of exogenous ochronosis has been disappointing.

Tretinoin gel, cryotherapy, and trichloroacetic acid have

been tried without benefit. Cases of exogenous ochronosis

successfully treated with dermabrasion and CO2 laser16 and

Q-switched ruby laser49 have been reported.

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Olumide et al.

Mercury

Mercury exists in three forms: organic, inorganic and

elemental. Mercury is a protoplasmic poison, which can be

absorbed by the respiratory tract as vapor or through the

skin and gastrointestinal tract as finely dispersed granules,

and excreted through the kidneys and colon. Cole50 observed

that the amount of mercury excreted by the kidneys was

proportional to the quantity applied on the skin. Until some

decades ago, mercury was ubiquitous in medicinal products

such as those used for treating syphilis, psoriasis, ringworm,

ophthalmic solutions, teething powders, and diuretics.

Though it is no longer commonly used in medications.

Mercury toxicity after topical applications was noted in

1923.51 Mercury toxicity may manifest in an acute or chronic

form. Acute toxicity usually manifests as a pneumonitis and

gastric discomfort. Chronic toxicity may be evidenced by

neurological manifestations and nephrotoxicity. Both organic

and inorganic preparations of mercury have been associated

with acute and chronic toxicity. Nephrotic syndrome due to

topical or systemic use of mercury has been well documented.1,52 Both membranous glomerulonephritis and

proliferative glomerulonephritis were found in patients

who had used mercury containing skin lightening creams.

Mercurious chloride, oxide and ammoniated mercury were

first introduced into the market during the first decade of the

20th century as the active ingredient in cosmetics and toiletries.

They eventually became popular as skin lighteners. Following

studies with electron microscope, mercury bleaches the skin

by probably inactivating the sulfhydryl enzymes.34,53 These

enzymes, which are called mercaptans due to their ability to

capture mercurial ions, then replace copper by competitive

inhibition leading to inactivation of the tyrosinase molecule

and interrupting melanin production. Paradoxically, chronic

use of mercury can also lead to increased pigmentation,

due to accumulation of mercury granules in the dermis.

These granules are absorbed via the skin appendages such

as the hair follicles and sebaceous glands into the dermis.

Deposition of mercury in keratin also leads to discoloration

and brittleness of the nails.51 Goeckermann54 noted that a

brown-gray discoloration of the face and neck (especially the

skin folds and eyelids) was associated with prolonged use of

mercury containing creams.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids bleach the skin. It is believed that they lighten

the skin due to inhibition of endogenous steroid production

and thus a decrease in precursor hormone levels. This precursor

hormone, propiocortin is also the precursor for melanocyte

stimulating hormone and thus, such negative feedback will

lead to decreased amounts of the hormone. Topical steroids

are also cytostatic to the epidermis. When used over a

prolonged period, they decrease the rate of epidermal turnover,

with fewer, abnormal, and less pigmented melanocytes on

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Complications of skin lightening cosmetics Report

59,60

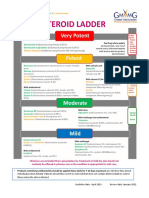

Table 3 Complications of topical steroids

Cutaneous

Atrophy of the skin (thinning and fine wrinkling)

Telangiectasia, purpura, persistent erythema

Skin fragility

Hypertrichosis

Perioral dermatitis

Pustular acneiform eruption (face) steroid rosacea

Folliculitis

Striae

Hypopigmentation

Steroid addiction syndrome

Predisposition and masking of cutaneous infection

(e.g. Tinea incognito, multiple filiform warts)

Allergic contact dermatitis

Ophthalmologic

Glaucoma

Cataracts

Endocrinologic

Cushingoid syndrome with moon facies,

buffalo humps, supraclavicular fat pads

Hyperglycaemia and diabetes mellitus

Suppression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

Suppression of growth in children

Menstrual irregularities

Edema

Electrolyte imbalance

Hypertension

Pseudotumor cerebri

Others

Aseptic necrosis of the head of femur

Predisposition to infection

Protein catabolism with negative nitrogen balance

Weakness, vertigo

Thrombophlebitis

Osteoporosis

histology. The skin lightening properties of these preparations have been found to be directly proportional to their

vasoconstrictor (blanching) effect.

Fluocinonide (Topsyn gel), Betamethasone dipropionate

(Diprosone), and Clobetasol propionate (Temovate) rate as

some of the strongest topical corticoids, and are among the

commonly used bleaching agents in Nigeria. They are readily

available in the market place among the battery of bleaching creams. When used as cosmetics, they are applied over

a large surface area for prolonged periods several months

to years. This factor, coupled with the occlusive effect of

environmental heat and humidity, promote percutaneous

absorption, and hence, complications. The possible complications of chronic corticosteroid use are shown in Table 3.

All these complications have been observed among chronic

bleachers in Nigeria.23,24,3135 Figs 714 show some of the

complications of long-term use of topical corticosteroids

as skin lightening cosmetics. The lower part of the axilla is

a favored site for steroid folliculitis (Fig. 7) and both sides

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

349

350

Report Complications of skin lightening cosmetics

Olumide et al.

Figure 7 Steroid folliculitis

are usually symmetrically affected. The striae are often

very wide (gaping) and erythematous (Figs 810). Overt

features of Cushings syndrome mooning of the face

and truncal obesity (Fig. 10) are frequently seen. Some of

them, at the time of presentation, have already developed

systemic manifestations like glucose intolerance and

hypertension.

Figure 8 Steroid folliculitis

Steroid addiction syndrome

The steroid addiction syndrome is the result of chronic daily

application for greater than a 1-month period of a potent or

moderately potent glucocorticosteroid preparation to the

facial skin, neck, scrotum or vulva. These tissues become

addicted to the topical steroid, so that withdrawing

the topical steroid results in severe burning which is only

relieved by further steroid applications. As application

continues, the patient experiences a rebound vasodilatation. Permanent redness of the facial skin eventuates,

with thinning and fine wrinkling of the skin. Indeed the

redness is so striking that the authors call the phenomenon

Lhomme rouge. For unexplainable reason, this permanent redness is more pronounced on male bleachers.

Furthermore, the thinning and wrinkling of the skin on

the neck gives a rippling pattern like the neck of a plucked

chicken, rather reminiscent of pseudoxanthoma elasticum

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

Figure 9 Steroid striae

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Olumide et al.

Figure 10 Cushions syndrome

Complications of skin lightening cosmetics Report

Figure 12 Tinea corporis

Figure 13 Tinea incognito in a child

Figure 11 Tinea faciei andPseudo-pseudo xanthoma elasticum

on the neck

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

351

352

Report Complications of skin lightening cosmetics

Olumide et al.

multiple tiny filiform warts, common on the neck and upper

trunk (Fig. 14).

Paradoxically, topical corticosteroid preparations may

induce allergic contact dermatitis.58 This complication should

be considered in any patient with an eczematous dermatitis

who becomes worse or is refractory to topical steroid

treatment.

References

Figure 14 Eruptive filiform wart (Pseudo Lesser-Trlat sign)

note gaping striae

hence, the authors code this complication of steroid as

pseudo-pseudoxanthoma elasticum. (Fig. 11) Some

bleachers claim that they developed the habit of chronic

steroid use while trying to treat acne. They experienced

good response initially due to the anti-inflammatory effect

of the steroids. Abruptly stopping the topical steroids

preparation will result in increased numbers of papules and

pustules over the subsequent days a rebound phenomenon.

The patient soon finds it difficult to stop the steroid and the

facial skin then develops persistent redness, and acneiform

papules and pustules located on the nose, chin, cheeks, and

lower eyelids acne rosacea.

Predisposition to infections

A very common observed complication of steroid on

chronic bleachers is dermatophyte infection. Tinea faciei

(Fig. 11) is common in these patients and may mimic cutaneous lupus erythematosus or rosacea.5557 Very bizarre and

extensive Tinea corposis and cruris (Fig. 12) are often seen,

which are readily transmitted to the spouse and baby.

Hence, it is common to find the trio of wife, husband and

baby with Tinea incognito. Older children are not part of

this phenomenon. The wife often transmits the fungal infection to husband and baby because of close body contact.

Figure 13 shows a child with Tinea incognito on the forehead, acquired from the infected skin of the mother while

feeding on her breast. The clinical presentation of these

steroid induced dermatophyte infections are often atypical

hence the term Tinea incognito. Tinea versicolor could

also be very extensive, and is usually pigmented with dirty

brown scales.

Also, multiple histologically proven viral warts are

frequently found on these chronic bleachers. They often

appear in an eruptive manner rather reminiscent of eruptive

seborrheic keratosis (Leser-Trlat sign). Hence the authors

call this complication pseudo-Leser-Trelat sign. They are

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

1 Barr RD, Rees PH, Cordy PE, et al. Nephrotic Syndrome in

Adult Africans in Nairobi. Br Med J 1972; 2: 131134.

2 Addo HA. A Clinical study of hydroquinone reaction

in skin bleaching in Ghana. Ghana Med J 1992; 26:

448453.

3 Findlay GH, Morrison JGL, Simson IW. Exogenous

ochronosis and pigmented colloid millium from

hydroquinone bleaching creams. Brit J Dermatol 1975;

613622.

4 Hardwick N, Van Gelder LW, Van Der Merwe CA, et al.

Exogenous ochronosis in an epidemiological study. Br J

Dermatol 1989; 120: 229238.

5 Muchadeyi E, Thompson S, Baker N. A Survey of the

constituents, availability and use of the skin lightening

creams in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med 1982; 29:

225227.

6 Cullison D, Abelle DC, OQuinn JL. Localised exogenous

ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983; 8: 882889.

7 Hoshaw RA, Zimmerman KG, Menter A. Ochronosis-like

Pigmentation from Hydroquinone. Arch Dermatol 1985;

121: 105108.

8 Boyle J, Kennedy CTC. British Cosmetic regulations

inadequate. Br Medical J 1984; 288299.

9 Oliveira DGB, Foster G, Savill J, et al. Membranous

Nephropathy caused by mercury-containing skin lightening

cream. Postgrad Med J 1989; 63: 303304.

10 Beddard AP, Plumtre CM. A further note on ochronosis

associated with carboluria. Quart J Med 1912; 5:

505507.

11 Addo HA. Squamous cell cancinoma associated with

prolonged bleaching. Ghana Med J 2000; 34: 3.

12 Mahe A, Keita S, Bobin P. Dermatologic complications of

the cosmetic use of bleaching agents in Bamako (Mali). Ann

Dermatol Venereol 1994; 121: 142146.

13 Otto M, Ahlemeyer C, Tasche H, et al. Endemic mercury

burden caused by a bleaching ointment in Balken refugees.

Gesundheitswesen 1994; 56: 686689.

14 Pick L. Uber die Ochronose. Klin Wochenschr 1906; 43:

478480.

15 Snider RL, Thiers BH. Exogenous ochronosis. J Am Acad

Dermatol 1993; 28: 662664.

16 Diven DG, Smith EB, Pupo RA, et al. Hydroquinoneinduced localized exogenous ochronosis treated with

dermabrasion and CO2 laser. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1990;

16: 10181022.

17 Ridley CM, Adams SJ. British cosmetic regulations

inadequate. Br Med J 1984; 288: 1537.

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Olumide et al.

18 Tidman MJ, Horton JJ, MacDonald DM. Hydroquinoneinduced ochronosis light and electron-microscopic

features. Clin Exp Dermatol 1986; 11: 224228.

19 Hoshaw RA, Zimmerman KG, Menter A. Ochronosislike

pigmentation from hydroquinone bleaching creams

in American blacks. Arch Dermatol 1985; 121: 105108.

20 Lawrence N, Reed R, Perret WJ, et al. Exogenous ochronosis

in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988; 18: 1207

1222.

21 Brauer EW. Safety of over-the-counter hydroquinone

bleaching creams. [letter]. Arch Dermatol 1985; 121: 1239.

22 Boyle J, Kennedy CTC. Hydroquinone concentrations in

skin lightening creams. Br J Derm 1986; 114: 502504.

23 Olumide YM. Cosmetic Hazards and Legislative Needs in

Nigeria. Nig Med Prac 1985; 9: 712.

24 Olumide YM. Abuse of Topical corticosteroids in Nigeria.

Nig. Med. Pract 1986; 11: 1712.

25 Olumide YM, Elesha SO. Hydroquinone induced

exogenous ochronosis. Nig Med Pract 1986; 11: 103106.

26 Olumide YM. Photodermatoses in Lagos. Int J Dermatol

1987; 26: 295299.

27 Olumide YM. Contact leukoderma. Nig Quart J Hosp

Medical 1989; 4: 5362.

28 Olumide YM. A Pictorial Self-Instructional Manual on

Common Skin Diseases. Nigeria: Heinemann Ibadan, 1990.

29 Olumide YM, Odunowo BD, Odiase AO. Regional

dermatoses in the African I. Facial hypermelanosis. Int J

Dermatol 1991; 30: 186189.

30 Cosmetic Product Regulations (Prohibition of bleaching

agents etc). Extraordinary Federal Republic Nigeria Official

Gazette 1995; 82 (31c).

31 Olumide YM. Cosmetic habits and Legislative need in

Nigeria. Paper presented at NAFDAC Workshop on

Cosmetics Safety Issues, 2002.

32 Adebajo SB. An Epidemiological Survey of the Use of

Cosmetic Skin Lightening Cosmetics among Traders in

Lagos. Nigeria. Personal Communication.

33 Ofondu EO. Cosmetic use of bleaching creams in Enugu.

Nigerian FMCP Dissertation, 2003.

34 Lerner AB, Fitzpatrick TB. Inhibition of melanin formation

by chemical agents. J Invest Dermatol 1952; 18: 119135.

35 Jimbow K, Obata H, Pathak MA, et al. Mechanism of

Depigmentation by Hydroquinone. J Invest Dermatol 1974;

62: 436.

36 Findlay GH. Ochronosis following skin bleaching with

hydroquinone (Editorial). J Am Acad Dermatol 1982; 6:

10921093.

37 Goldsmith LA. Cutaneous changes in errors of amino acid

metabolism: alkaptonuria. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ,

Wolff K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF, eds. Dermatology in

General Medicine, Chap 148. New York: McGraw-Hill,

1993: 18411845.

38 Jackyk WK. Annular granulomatous lesions in exogenous

ochronosis are manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J

Dermatopathol 1995; 17: 1822.

39 Jordaan HF, Van Niekerk DJT. Transepidermal elimination

2008 The International Society of Dermatology

Complications of skin lightening cosmetics Report

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

in exogenous ochronosis. Am J Dermatopathol 1991; 13:

418424.

Connor T, Braunstein B. Off-center fold: hyperpgimentation

following the use of bleaching creams: localized

exogenous ochronosis. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:

105106.

Ruocco V, Florio M. Fish-odor syndrome: an olfactory

diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 1995; 34: 92 93.

Attwood HD, Clifton S, Mitchell RE, et al. A histological,

histochemical and ultrastructural study of dermal

ochronosis. Pathology (Phila) 1971; 3: 115.

Tidman MJ, Horton JJ, Macdonald DM, et al.

Hydroquinone-induced ochronosis: Light and electronmicroscopic features. Clin Exp Dermatol 1986; 11: 224.

Zannoni VG, Lomtevas N, Goldfinger S, et al. Oxidation of

homogentisic acid to ochronotic pigment in connective

tissue. Biochem Biophys Acta 1969; 177: 94.

Penneys ND. Ochronosislike pigmentation from

hydroquinone bleaching creams. [letter]. Arch Dermatol

1985; 121: 1239.

Phillips JI, Isaacson C, Carman H. Ochronosis in black

South Africans who used skin lighteners. Am J

Dermatopathol 1986; 8: 1421.

Hull PR, Procter PR. The melanocyte: An essential link in

hydroquinone induced ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol

1990; 22: 529531.

Dogliotte M, Liebowitz M. Granulomatous ochronosis a

cosmetic-induced skin disorder in blacks. S Afr Med J 1979;

56: 757760.

Kramer KE, Lopez A, Stefanato CM, et al. Exogenous

ochronosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 869871.

Cole HN, Schreider N, Sollman J. Mercurial ointments in

the treatment of syphilis. Arch Dermatol 1930; 21: 372.

Alexander A, Mendel K. Chronishe Quecksilbervertifang

durch langdauernden Gebrauch einer Sommersprossensalbe. Deutsh Med Wschr 1923; 49: 1021.

Silverberg DS, McCall JT, Hunt JC. Nephrotic syndrome

with use of ammoniated mercury. Arch Intern Med 1967;

120: 583585.

Wealtherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA. Chemical

and physical injuries. Climatic and occupational

diseases. Oxford Textbook of Medicine 1985;

6.136.14.

Goeckermann WH. A peculiar discolouration of the skin.

JAMA 1975; 84: 506507.

Meymandi S, Wiseman MC, Crawford RI. Tinea faciei

mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a

histopathologic case report. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003; 48:

S7S8.

Singh R, Bharu K, Ghazali W, et al. Tinea faciei mimicking

lupus erythematosus. Cutis 1994; 53: 297298.

Lee SJ, Choi HJ, Hann SK. Rosacea-like tinea faciei. Int J

Dermatol 1999; 38: 479480.

Lutz ME, Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA, et al. Allergic contact

dermatitis to topical application of corticosteroids. Mayo

Clin Proc 1997; 72: 1141.

International Journal of Dermatology 2008, 47, 344 353

353

Você também pode gostar

- Risks of Mercury in Skin LighteningDocumento4 páginasRisks of Mercury in Skin LighteningDanyal2222Ainda não há avaliações

- Determination of Hydroquinone Content in Skin-Lightening Creams in Lagos, NigeriaDocumento5 páginasDetermination of Hydroquinone Content in Skin-Lightening Creams in Lagos, NigeriaftmrdrAinda não há avaliações

- Skin Lightening PreparationsDocumento7 páginasSkin Lightening PreparationsMarina BesselAinda não há avaliações

- Health Ministry Bans 9 Cosmetic ProductsDocumento11 páginasHealth Ministry Bans 9 Cosmetic ProductsFarah AmeliaAinda não há avaliações

- Personal-Care Cosmetic Practices in Pakistan: Current Perspectives and ManagementDocumento13 páginasPersonal-Care Cosmetic Practices in Pakistan: Current Perspectives and Managementummekhadija ashraf293Ainda não há avaliações

- SKIN CARE MERCURY RISKDocumento5 páginasSKIN CARE MERCURY RISKAdi PrayogaAinda não há avaliações

- The Phenomenon of Skin Lightening: Is It Right To Be Light?: AuthorsDocumento5 páginasThe Phenomenon of Skin Lightening: Is It Right To Be Light?: AuthorsGiovan GaulAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Hawa, 2017 PDFDocumento6 páginasJurnal Hawa, 2017 PDFIzmy PermataAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 5: Pharmacology Perspective in CosmeticsDocumento5 páginasTopic 5: Pharmacology Perspective in CosmeticsgaluhAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics Side EffectsDocumento17 páginasCosmetics Side EffectsIrwandyAinda não há avaliações

- Alora Night Glowing Cream DHM 2033Documento4 páginasAlora Night Glowing Cream DHM 2033Muhammad ImranAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics Are Substances Used To Enhance: ComponentDocumento10 páginasCosmetics Are Substances Used To Enhance: Componentsiti_wahid_2Ainda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of A Kojic Acid, PDFDocumento6 páginasEvaluation of A Kojic Acid, PDFvanitha13Ainda não há avaliações

- Jps R 06101406Documento4 páginasJps R 06101406Afiqah RahahAinda não há avaliações

- How Can Skincare Products Be ImprovedDocumento4 páginasHow Can Skincare Products Be ImprovedAnnisa RumAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmeceuticals - Current Trends and Market AnalysisDocumento3 páginasCosmeceuticals - Current Trends and Market AnalysisChiper Zaharia DanielaAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Related LiteratureDocumento7 páginasReview of Related LiteratureJamie HaravataAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainability 13 08786Documento13 páginasSustainability 13 08786Rillah LeswanaAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of Skin Lightening Cream Agents - Hydroquinone and Kojic Acid, On The Skin of Adult Female Experimental RatsDocumento7 páginasEffects of Skin Lightening Cream Agents - Hydroquinone and Kojic Acid, On The Skin of Adult Female Experimental Ratsindah ayuAinda não há avaliações

- Chemical Peeling in Ethnic Skin: An Update: What's Already Known About This Topic?Documento9 páginasChemical Peeling in Ethnic Skin: An Update: What's Already Known About This Topic?Rojas Evert AlonsoAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics Overview: Quality Control ParametersDocumento77 páginasCosmetics Overview: Quality Control ParametersGulshan DangiAinda não há avaliações

- Growing Fashion Craze: Threat To Public Health and MicrobesDocumento47 páginasGrowing Fashion Craze: Threat To Public Health and MicrobesshivahariAinda não há avaliações

- Odumosu and EkweDocumento4 páginasOdumosu and EkwePutri Nur HandayaniAinda não há avaliações

- Jcad 15 2 12Documento6 páginasJcad 15 2 12Putri IcaAinda não há avaliações

- Beauty Products Causing Cancer: Bachelor of PharmacyDocumento19 páginasBeauty Products Causing Cancer: Bachelor of PharmacyKumar AvinashAinda não há avaliações

- Environmental Research: Mètogbé Honoré Gbetoh, Marc AmyotDocumento8 páginasEnvironmental Research: Mètogbé Honoré Gbetoh, Marc AmyotMaria StfAinda não há avaliações

- Mercury-Laden and Other Harmful Substances in Cosmetic Products BannedDocumento2 páginasMercury-Laden and Other Harmful Substances in Cosmetic Products BannedEmilyn Mata CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Cosmetics and Its Health RisksDocumento9 páginas6 Cosmetics and Its Health Riskssabrina pusitAinda não há avaliações

- Article 007Documento6 páginasArticle 007Dyah Putri Ayu DinastyarAinda não há avaliações

- Elc550 Test - April2019Documento5 páginasElc550 Test - April2019Muhammad Azri HaziqAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics FactsheetDocumento5 páginasCosmetics Factsheetapi-264144691100% (1)

- Comments From The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene On FDA'sDocumento3 páginasComments From The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene On FDA'sMarina BesselAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics 07 00092Documento14 páginasCosmetics 07 00092ritaparautaAinda não há avaliações

- Dermatologicals in The PhilippinesDocumento8 páginasDermatologicals in The PhilippinesellochocoAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetic and HealthDocumento3 páginasCosmetic and HealthharhoneyAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetics' Safety: Gray Areas With Darker InsideDocumento6 páginasCosmetics' Safety: Gray Areas With Darker InsideA. K. MohiuddinAinda não há avaliações

- FINALIZED 2 Nigeria Call To Action Communique To EU - AAPNDocumento10 páginasFINALIZED 2 Nigeria Call To Action Communique To EU - AAPNOfoegbu Donald IkennaAinda não há avaliações

- Biodeterioration of Cosmetic ProductsDocumento21 páginasBiodeterioration of Cosmetic ProductsSundaralingam RajAinda não há avaliações

- Carcinogenic Effects of Personal Care ProductsDocumento23 páginasCarcinogenic Effects of Personal Care ProductsFatima KhalidAinda não há avaliações

- A Case Report On Hydroquinone Induced Exogenous OchronosisDocumento3 páginasA Case Report On Hydroquinone Induced Exogenous Ochronosisindah ayuAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetic Testing On AnimalsDocumento19 páginasCosmetic Testing On AnimalsNhi Hoàng Lê NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Toxic-free hygiene products: Time to demand changeDocumento5 páginasToxic-free hygiene products: Time to demand changeNataliaAinda não há avaliações

- 0815 COVID-19 and Frequent Use of Hand Sanitizers - Human Health and Environmental Hazards by Exposure PathwaysDocumento50 páginas0815 COVID-19 and Frequent Use of Hand Sanitizers - Human Health and Environmental Hazards by Exposure PathwaysHenrico ImpolaAinda não há avaliações

- Side Effects of CosmeticsDocumento8 páginasSide Effects of CosmeticsTauqeerAhmadRajput100% (1)

- Buletin Farmasi 09/2013Documento12 páginasBuletin Farmasi 09/2013afiq83Ainda não há avaliações

- Fake Cosmetics Product Effects On HealthDocumento5 páginasFake Cosmetics Product Effects On Healthdiana ramzi50% (2)

- Mercury in Skin Whitening Cream PDFDocumento28 páginasMercury in Skin Whitening Cream PDFCristel SerranoAinda não há avaliações

- COSMETICS AND CONSUMERS: A GUIDE FOR INDUSTRY AND CONSUMERSDocumento30 páginasCOSMETICS AND CONSUMERS: A GUIDE FOR INDUSTRY AND CONSUMERSakshayprasadAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic On The Cosmetic Ingredients IndustryDocumento17 páginasImpact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic On The Cosmetic Ingredients IndustryZahra GhalamiAinda não há avaliações

- Teen Perceptions Cosmetics Risks AmbonDocumento9 páginasTeen Perceptions Cosmetics Risks AmbonRiskayanti RamadhaniAinda não há avaliações

- EU Recalls 24 Microbe-Contaminated Cosmetics 2005-2008Documento4 páginasEU Recalls 24 Microbe-Contaminated Cosmetics 2005-2008AghniaAinda não há avaliações

- CHEMISTRY PROJECT Shreya ThokalDocumento33 páginasCHEMISTRY PROJECT Shreya Thokal28-Shreya ThokalAinda não há avaliações

- 1.1 Background of The Study: Chen, Qiushi (2009)Documento10 páginas1.1 Background of The Study: Chen, Qiushi (2009)John Fetiza ObispadoAinda não há avaliações

- (Cosmetic Science and Technology Series) Jungermann, Eric - Glycerine - A Key Cosmetic Ingredient-CRC Press - Taylor and Francis (2017)Documento477 páginas(Cosmetic Science and Technology Series) Jungermann, Eric - Glycerine - A Key Cosmetic Ingredient-CRC Press - Taylor and Francis (2017)Hoàng Ngọc AnhAinda não há avaliações

- Rise of the Vegan Cosmetics Industry in IndiaDocumento23 páginasRise of the Vegan Cosmetics Industry in IndiaPrativa KumariAinda não há avaliações

- Cosmetic Dermatology: Products and ProceduresNo EverandCosmetic Dermatology: Products and ProceduresNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Cosmetics for the Skin: Physiological and Pharmaceutical ApproachNo EverandCosmetics for the Skin: Physiological and Pharmaceutical ApproachAinda não há avaliações

- Look Great, Live Green: Choosing Bodycare Products that Are Safe for You, Safe for the PlanetNo EverandLook Great, Live Green: Choosing Bodycare Products that Are Safe for You, Safe for the PlanetNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (40)

- Frankincense Oil Cancer RemediesDocumento3 páginasFrankincense Oil Cancer RemediesManea LaurentiuAinda não há avaliações

- Asthma: Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment Adherence: Gerri KaufmanDocumento8 páginasAsthma: Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment Adherence: Gerri KaufmandessyAinda não há avaliações

- Corticosteroid Classes - A Quick Reference Guide Including Patch Test Substances and Cross-ReactivityDocumento5 páginasCorticosteroid Classes - A Quick Reference Guide Including Patch Test Substances and Cross-ReactivityBreiner PeñarandaAinda não há avaliações

- Florinef SPCDocumento7 páginasFlorinef SPCJohn GoulianosAinda não há avaliações

- Topical Corticosteroid Supply Shortage GuidanceDocumento3 páginasTopical Corticosteroid Supply Shortage GuidancesyahrulroziAinda não há avaliações

- Pharmacology Exam 3 Pharmacology Exam 3Documento44 páginasPharmacology Exam 3 Pharmacology Exam 3LillabinAinda não há avaliações

- Double-Blind Clinical Topical Steroids Uveitis: Trial of in AnteriorDocumento6 páginasDouble-Blind Clinical Topical Steroids Uveitis: Trial of in Anteriorguugle gogleAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Medical History Form English and ArabicDocumento5 páginasDental Medical History Form English and ArabicAbdulrahman QA/QCAinda não há avaliações

- VentolinDocumento13 páginasVentolinFitrah NstAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenocorticosteroids & Adrenocortical AntagonistsDocumento20 páginasAdrenocorticosteroids & Adrenocortical Antagonistsapi-3859918Ainda não há avaliações

- Mellen Center MS Relapse TreatmentDocumento5 páginasMellen Center MS Relapse TreatmentNgakanAinda não há avaliações

- Internal Medicine - DermatologyDocumento125 páginasInternal Medicine - DermatologySoleil DaddouAinda não há avaliações

- Name of Drug Mechanism of Action Indications Contraindication Side Effects Nursing Responsibilities Generic Name: BeforeDocumento5 páginasName of Drug Mechanism of Action Indications Contraindication Side Effects Nursing Responsibilities Generic Name: BeforeWestley RubinoAinda não há avaliações

- O Papel Das Drogas Antiparasitárias e Corticóides No Tratamento Da Covid-19Documento14 páginasO Papel Das Drogas Antiparasitárias e Corticóides No Tratamento Da Covid-19Guilherme marinhoAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Multiple Sclerosis RelapseDocumento16 páginasAcute Multiple Sclerosis RelapseHabib G. Moutran BarrosoAinda não há avaliações

- Cushings Addisons and Acromegaly EdDocumento45 páginasCushings Addisons and Acromegaly EdAny PopAinda não há avaliações

- 2 2015 Nsaid Analgetik AntipiretikaDocumento65 páginas2 2015 Nsaid Analgetik AntipiretikasekarAinda não há avaliações

- Medicine MOMDocumento7 páginasMedicine MOMsushilshsAinda não há avaliações

- ADDISONS DSE - Etio Trends&Issues + DSDocumento9 páginasADDISONS DSE - Etio Trends&Issues + DSgraceAinda não há avaliações

- Drug StudyDocumento17 páginasDrug StudyKenneth ManalangAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Study #4Documento7 páginasDrug Study #4Sarah Kaye BañoAinda não há avaliações

- Mometasone FuroatDocumento8 páginasMometasone FuroatAnonymous ZrLxxRUr9zAinda não há avaliações

- CH 52 Assessment and Management of Patients With Endocrine DisordersDocumento15 páginasCH 52 Assessment and Management of Patients With Endocrine Disordersfiya33Ainda não há avaliações

- Oral CorticosteroidsDocumento29 páginasOral CorticosteroidsloraAinda não há avaliações

- Topical Corticosteroid PotencyDocumento2 páginasTopical Corticosteroid PotencyTeffi Widya JaniAinda não há avaliações

- Topical SteroidsDocumento10 páginasTopical SteroidsMariaAinda não há avaliações

- VitiligoDocumento24 páginasVitiligoAnonymous hTivgzixVNAinda não há avaliações

- Stress y ConceptosDocumento10 páginasStress y ConceptosVivian FTAinda não há avaliações

- Prednisone TabDocumento10 páginasPrednisone TabrantiadrianiAinda não há avaliações

- GM Steroid LadderDocumento2 páginasGM Steroid LadderRenee McGuinnessAinda não há avaliações