Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

DPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws June2015 PDF

Enviado por

webmaster@drugpolicy.orgDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

DPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws June2015 PDF

Enviado por

webmaster@drugpolicy.orgDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

911 Good Samaritan Laws:

Preventing Overdose

Deaths, Saving Lives

June 2015

Overdose Deaths: A Serious National Problem

Overdose deaths rates nationwide more than doubled

between 1999 and 2013.1 According to the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 43,982 people

died from drug overdoses in 2013 an average of 120

people a day.2 Overdoses resulted in more deaths

than HIV/AIDS, homicide or car accidents.3

Overdose has now surpassed motor vehicle

accidents as the leading cause of injury-related

death in the U.S.4

Nationally, more overdose deaths are caused by

prescription drugs than all illegal drugs combined.5

Legal prescription opioids, such as OxyContin and

Vicodin, are driving the increase in overdose deaths

nationwide causing more than 16,000 deaths in

2013.6 For more than a decade, prescription opioid

overdose deaths have outnumbered both heroin and

cocaine overdose deaths (although heroin overdose

deaths have increased in recent years).7

Moreover, as states have attempted to restrict access

to opioids, evidence indicates that some opioiddependent people have switched from prescription

painkillers to heroin.8

The tragedy is that many of these deaths could have

been prevented.

911 Good Samaritan Laws: A Practical Solution

That Can Save Lives

The chance of surviving an overdose, like that of

surviving a heart attack, depends greatly on how fast

one receives medical assistance. Multiple studies

show that most deaths actually occur one to three

hours after the victim has initially ingested or injected

drugs.9 The time that elapses before an overdose

becomes a fatality presents a vital opportunity to

intervene and seek medical help.

Witnesses to heart attacks rarely think twice about

calling 911, but witnesses to an overdose often

hesitate to call for help or, in many cases, simply dont

make the call.10 The most common reason people cite

for not calling 911 is fear of police involvement.11

People using drugs illegally often fear arrest, even in

cases where they need professional medical

assistance for a friend or family member. Furthermore,

severe penalties for possession and use of illicit drugs,

including state laws that impose criminal charges on

individuals who provide drugs to someone who

subsequently dies of an overdose, only intensify the

fear that prevents many witnesses from seeking

emergency medical help.12

Risk of criminal prosecution or civil litigation can

deter medical professionals, drug users and

bystanders from aiding overdose victims. Wellcrafted legislation can provide simple protections

to alleviate these fears, improve emergency

overdose responses, and save lives.

An important solution to encourage overdose

witnesses to seek medical help is to exempt them from

arrest and criminal prosecution through the adoption of

911 Good Samaritan immunity laws.

Drug Policy Alliance | 131 West 33rd Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10001

nyc@drugpolicy.org | 212.613.8020 voice | 212.613.8021 fax

Good Samaritan immunity laws provide protection from

arrest and prosecution for witnesses who call 911.

Such legislation does not protect people from arrest for

other offenses, such as selling or trafficking drugs.

This policy protects only the caller and overdose victim

from arrest and prosecution for simple drug

possession, possession of paraphernalia, and/or being

under the influence.

The policy prioritizes saving lives over arrests for

possession.

Laws encouraging overdose witnesses and victims to

seek medical attention may also be accompanied by

training for law enforcement, EMS and other

emergency and public safety personnel.13 Indeed, a

recent survey of law enforcement officers indicated a

desire to be more involved in overdose prevention and

response, suggesting the potential for broader law

enforcement engagement around this pressing public

health crisis.14

A Growing National Movement to Prevent

Overdose Fatalities

In State Legislatures: In 2007, New Mexico was the

first state in the nation to pass 911 Good Samaritan

legislation. Since then, twenty-seven additional states

Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut,

1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Quickstats: Rates of Deaths from

Drug Poisoning and Drug Poisoning Involving Opioid Analgesics United States,

19992013," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64, no. 1 (2015).

2

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), "Prescription Drug Overdose

in the United States: Fact Sheet,"

http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/overdose/facts.html.

3

Ibid.

4

Ibid.

5

C. M. Jones, K. A. Mack, and L. J. Paulozzi, "Pharmaceutical Overdose Deaths,

United States, 2010," JAMA 309, no. 7 (2013); Margaret Warner, Holly

Hedegaard, and Chen Li Hui, "Trends in Drug-Poisoning Deaths Involving Opioid

Analgesics and Heroin: United States, 19992012," (National Center for Health

Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014).

6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Table 40. Specific Drugs Involved

in Drug Poisoning Deaths, 2008-2013,"

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/heroin_deaths.pdf; Center for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC), "Prescription Drug Overdose in the United States: Fact

Sheet".

7

L. J. Paulozzi, "Prescription Drug Overdoses: A Review," J Safety Res 43, no. 4

(2012); Warner, Hedegaard, and Li Hui, "Trends in Drug-Poisoning Deaths

Involving Opioid Analgesics and Heroin: United States, 19992012; Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, "Quickstats: Rates of Deaths from Drug

Poisoning and Drug Poisoning Involving Opioid Analgesics United States,

19992013; "Table 40. Specific Drugs Involved in Drug Poisoning Deaths, 20082013".

8

Warner, Hedegaard, and Li Hui, "Trends in Drug-Poisoning Deaths Involving

Opioid Analgesics and Heroin: United States, 19992012; K. Michelle Peavy et al.,

"Hooked on Prescription-Type Opiates Prior to Using Heroin: Results from a

Survey of Syringe Exchange Clients," Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 44, no. 3

(2012); R. A. Pollini et al., "Problematic Use of Prescription-Type Opioids Prior to

Heroin Use among Young Heroin Injectors," Subst Abuse Rehabil 2, no. 1 (2011).

9

Peter J. Davidson et al., "Witnessing Heroin-Related Overdoses: The

Experiences of Young Injectors in San Francisco," Addiction 97, no. 12 (2002).

Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota,

Mississippi, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North

Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode

Island, Vermont, Washington State, West Virginia and

Wisconsin as well as the District of Columbia, have

passed such laws.15

Initial results from an evaluation of Washington States

Good Samaritan law, adopted in 2010, found that

police officers and paramedics were largely unaware

of the law suggesting the need for continued training,

education and collaboration with law enforcement and

other public safety personnel. However, 88 percent of

people who use opioids said they would be more likely,

and less afraid, to call 911 in the event of a future

overdose after learning about the law.16

US Conference of Mayors: In 2008, the United States

Conference of Mayors unanimously adopted a

resolution calling for 911 Good Samaritan policies that

could save thousands of lives by encouraging

immediate medical intervention for drug overdoses

before they become fatal.17

On College Campuses: Today, 911 Good Samaritan

policies are in effect on over 90 U.S. college

campuses. Such policies have been proven to

encourage students to call for help in the event of an

alcohol or other drug overdose.18

10

M. Tracy et al., "Circumstances of Witnessed Drug Overdose in New York City:

Implications for Intervention," Drug Alcohol Depend 79, no. 2 (2005).

11

Davidson et al., "Witnessing Heroin-Related Overdoses: The Experiences of

Young Injectors in San Francisco; K. C. Ochoa et al., "Overdosing among Young

Injection Drug Users in San Francisco," Addict Behav 26, no. 3 (2001); Robin A.

Pollini et al., "Response to Overdose among Injection Drug Users," American

journal of preventive medicine 31, no. 3 (2006); Tracy et al., "Circumstances of

Witnessed Drug Overdose in New York City: Implications for Intervention."

12

C. J. Banta-Green et al., "Police Officers' and Paramedics' Experiences with

Overdose and Their Knowledge and Opinions of Washington State's Drug

Overdose-Naloxone-Good Samaritan Law," J Urban Health 90, no. 6 (2013).

13

Traci C. Green et al., "Law Enforcement Attitudes toward Overdose Prevention

and Response," Drug and Alcohol Dependence 133, no. 2 (2013); Banta-Green et

al., "Police Officers' and Paramedics' Experiences with Overdose and Their

Knowledge and Opinions of Washington State's Drug Overdose-Naloxone-Good

Samaritan Law."

14

Green et al., "Law Enforcement Attitudes toward Overdose Prevention and

Response."

15

Utah and Indiana adopted laws providing for mitigation in cases of good-faith

reporting of an overdose, but these states do not provide immunity.

16

Banta-Green CJ et al., "Washingtons 911 Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Law

- Initial Evaluation Results," (Alcohol & Drug Abuse Institute, University of

Washington,, 2011); Banta-Green et al., "Police Officers' and Paramedics'

Experiences with Overdose and Their Knowledge and Opinions of Washington

State's Drug Overdose-Naloxone-Good Samaritan Law."

17

U.S. Conference of Mayors, "Saving Lives, Saving Money: City-Coordinated

Drug Overdose Prevention," in U.S. Conference of Mayors 76th Annual Meeting

(Miami2008).

18

Deborah K. Lewis and Timothy C. Marchell, "Safety First: A Medical Amnesty

Approach to Alcohol Poisoning at a U.S. University," International Journal of Drug

Policy 17, no. 4 (2006).

Drug Policy Alliance | 131 West 33rd Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10001

nyc@drugpolicy.org | 212.613.8020 voice | 212.613.8021 fax

Page 2

Você também pode gostar

- DPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws Feb2015 PDFDocumento2 páginasDPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws Feb2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- DPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws Jan2015 PDFDocumento2 páginasDPA Fact Sheet 911 Good Samaritan Laws Jan2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- DPA - Fact Sheet - 911 Good Samaritan Laws - June 2013Documento2 páginasDPA - Fact Sheet - 911 Good Samaritan Laws - June 2013webmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Fact Sheet - 911 Good Samaritan - 0Documento2 páginasFact Sheet - 911 Good Samaritan - 0webmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Drug War Crimes: The Consequences of ProhibitionNo EverandDrug War Crimes: The Consequences of ProhibitionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- Senate Hearing, 108TH Congress - Prescription Drug Abuse and Diversion: The Role of Prescription Drug Monitoring ProgramsDocumento61 páginasSenate Hearing, 108TH Congress - Prescription Drug Abuse and Diversion: The Role of Prescription Drug Monitoring ProgramsScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Dpa Drug Induced Homicide Report 0Documento80 páginasDpa Drug Induced Homicide Report 0Tahsina A MalihaAinda não há avaliações

- War On Drugs EssayDocumento4 páginasWar On Drugs Essayapi-450946351Ainda não há avaliações

- Principles of Addictions and the Law: Applications in Forensic, Mental Health, and Medical PracticeNo EverandPrinciples of Addictions and the Law: Applications in Forensic, Mental Health, and Medical PracticeAinda não há avaliações

- EndingTheWarOnDurgs BriefDocumento10 páginasEndingTheWarOnDurgs BriefTamizh TamizhAinda não há avaliações

- OGL 345 Legalizing Illicit DrugsDocumento12 páginasOGL 345 Legalizing Illicit DrugsShawn MurphyAinda não há avaliações

- Chelseejensen Criminaljustice FinalDocumento12 páginasChelseejensen Criminaljustice Finalapi-253454328Ainda não há avaliações

- After ProhibitionDocumento16 páginasAfter ProhibitionChris JosephAinda não há avaliações

- DPA Fact Sheet - Approaches To Decriminalization - (Feb. 2016) PDFDocumento4 páginasDPA Fact Sheet - Approaches To Decriminalization - (Feb. 2016) PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (2)

- Group Issue GuideDocumento34 páginasGroup Issue Guideapi-548607005Ainda não há avaliações

- Speaking Out Speaking Out Speaking Out Speaking Out Speaking OutDocumento28 páginasSpeaking Out Speaking Out Speaking Out Speaking Out Speaking Outlelouch_damienAinda não há avaliações

- Illegal and Legal Drug Use: A Review of Literature of Controlled Substances Samuel Retana UT El PasoDocumento12 páginasIllegal and Legal Drug Use: A Review of Literature of Controlled Substances Samuel Retana UT El Pasoapi-240482854Ainda não há avaliações

- Illicit Drugs: The Argument For DecriminalizationDocumento11 páginasIllicit Drugs: The Argument For DecriminalizationAlex OmiotekAinda não há avaliações

- FinalDocumento8 páginasFinalapi-237602825Ainda não há avaliações

- Questions and Answers: Overdose Prevention CampaignDocumento2 páginasQuestions and Answers: Overdose Prevention Campaignwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Oklahoma Commission On Opioid Abuse Final ReportDocumento12 páginasOklahoma Commission On Opioid Abuse Final ReportOKCFOXAinda não há avaliações

- Illicit Drugs: The Argument For DecriminalizationDocumento9 páginasIllicit Drugs: The Argument For DecriminalizationAlex OmiotekAinda não há avaliações

- Fact Sheet - Drug Testing For Public Benefits and TANFDocumento1 páginaFact Sheet - Drug Testing For Public Benefits and TANFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Con: Legalising Drugs Would Create Addicts: The GuardianDocumento5 páginasCon: Legalising Drugs Would Create Addicts: The GuardianLuis Alfredo Pulido RosasAinda não há avaliações

- Foreign StudiesDocumento5 páginasForeign StudiesNelson Cervantes ArasAinda não há avaliações

- DPA Fact Sheet - Drug War Mass Incarceration and Race - (Feb. 2016) PDFDocumento3 páginasDPA Fact Sheet - Drug War Mass Incarceration and Race - (Feb. 2016) PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (1)

- Overdose Prevention Campaign: Good Samaritan Questions and AnswersDocumento2 páginasOverdose Prevention Campaign: Good Samaritan Questions and Answerswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Turning The Page On The War On Drugs: A Balanced Approach To Bending The Curve of The Overdose Epidemic by Connor KubeisyDocumento9 páginasTurning The Page On The War On Drugs: A Balanced Approach To Bending The Curve of The Overdose Epidemic by Connor KubeisyHoover InstitutionAinda não há avaliações

- DPA - Fact Sheet - Medical - Marijuana - Jan2015 PDFDocumento3 páginasDPA - Fact Sheet - Medical - Marijuana - Jan2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Marijuana Prohibition FactsDocumento5 páginasMarijuana Prohibition FactsMPPAinda não há avaliações

- DPA Fact Sheet Drug War Mass Incarceration and Race Jan2015 PDFDocumento2 páginasDPA Fact Sheet Drug War Mass Incarceration and Race Jan2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Critical Thinking Assignment FinalDocumento10 páginasCritical Thinking Assignment Finalapi-516694258Ainda não há avaliações

- CannabisDocumento15 páginasCannabisGoombombAinda não há avaliações

- The Lancet: Public Health and International Drug Policy (2016)Documento54 páginasThe Lancet: Public Health and International Drug Policy (2016)Ben Adlin67% (3)

- DPA Ally Summer 2011 FinalDocumento8 páginasDPA Ally Summer 2011 Finalwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Decriminalizing Drug Use Is A Necessary Step, But It Won't End The Opioid Overdose CrisisDocumento1 páginaDecriminalizing Drug Use Is A Necessary Step, But It Won't End The Opioid Overdose CrisisJoe NicolettiAinda não há avaliações

- Association of Schools of Public HealthDocumento8 páginasAssociation of Schools of Public HealthShane BoyleAinda não há avaliações

- Report 123Documento5 páginasReport 123api-302507329Ainda não há avaliações

- Leonard Paulozzi TestimonyDocumento4 páginasLeonard Paulozzi TestimonyJames LindonAinda não há avaliações

- Argumentative Essay Medical MarijuanaDocumento7 páginasArgumentative Essay Medical MarijuanaMaxim Dahan100% (1)

- Collage FinalDocumento1 páginaCollage Finalapi-273731315Ainda não há avaliações

- Internet System For Tracking Over-Prescribing (I-Stop) : New York State O Ce of The Attorney GeneralDocumento43 páginasInternet System For Tracking Over-Prescribing (I-Stop) : New York State O Ce of The Attorney GeneralNewsdayAinda não há avaliações

- Mainly in The Main Drug Consumer, The United States, There Won't EvenDocumento5 páginasMainly in The Main Drug Consumer, The United States, There Won't EvenRonik MalikAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Control Policies-2Documento14 páginasDrug Control Policies-2api-545354167Ainda não há avaliações

- CP Legalize DrugsDocumento13 páginasCP Legalize DrugsDanAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review of The Drug War in The United StatesDocumento18 páginasLiterature Review of The Drug War in The United Statesapi-317818374100% (2)

- Nuevas Drogas SinteticasDocumento2 páginasNuevas Drogas SinteticascaluveraAinda não há avaliações

- Is Kemer Kemer KemeDocumento2 páginasIs Kemer Kemer KemeAlbert YumolAinda não há avaliações

- Example Thesis About Illegal DrugsDocumento4 páginasExample Thesis About Illegal DrugsPaperWritingHelpSyracuse100% (3)

- War On DrugsDocumento7 páginasWar On DrugsLj Brazas SortigosaAinda não há avaliações

- Australia21 Illicit Drug Policy ReportDocumento28 páginasAustralia21 Illicit Drug Policy ReportAaron Troy SmallAinda não há avaliações

- MARIJUANA USE BY YOUNG PEOPLE: The Impact of State Medical Marijuana Laws (2011)Documento20 páginasMARIJUANA USE BY YOUNG PEOPLE: The Impact of State Medical Marijuana Laws (2011)CDSMGMTAinda não há avaliações

- Drogas y Prisiones en Am LatDocumento100 páginasDrogas y Prisiones en Am LatJag RoAinda não há avaliações

- October 17, 2011: Thai Policeman. Photo by Rico GustavDocumento6 páginasOctober 17, 2011: Thai Policeman. Photo by Rico GustavmarcelemanuelliantoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction and Analytical Report PDFDocumento111 páginasIntroduction and Analytical Report PDFJoão Pedro GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Opioid Response Plan 041817 PDFDocumento17 páginasOpioid Response Plan 041817 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- New Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & CommunitiesDocumento1 páginaNew Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & Communitieswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- NewSolutions MarijuanaReformArrestConvictionConsequences PDFDocumento1 páginaNewSolutions MarijuanaReformArrestConvictionConsequences PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- New Solutions Marijuana Reform Regulation Works Final PDFDocumento1 páginaNew Solutions Marijuana Reform Regulation Works Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- NewSolutions MarijuanaReformExecSummary PDFDocumento1 páginaNewSolutions MarijuanaReformExecSummary PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- New Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & CommunitiesDocumento1 páginaNew Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & Communitieswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- VivitrolFactSheet PDFDocumento5 páginasVivitrolFactSheet PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (1)

- Prop 64 Resentencing Guide PDFDocumento17 páginasProp 64 Resentencing Guide PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (1)

- New Solutions Marijuana Reform Regulation Works Final PDFDocumento1 páginaNew Solutions Marijuana Reform Regulation Works Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Prop64-Quality-Drug-Education-CA Teens PDFDocumento2 páginasProp64-Quality-Drug-Education-CA Teens PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Sign On Letter Opposing HJ Res 42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Applicants - FINAL - 031417 - 2 PDFDocumento4 páginasSign On Letter Opposing HJ Res 42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Applicants - FINAL - 031417 - 2 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Sign On Letter Opposing HJRes42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Ap PDFDocumento4 páginasSign On Letter Opposing HJRes42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Ap PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- DPA Annual Report - 2016 PDFDocumento23 páginasDPA Annual Report - 2016 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Sign On Letter Opposing HJRes42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Ap PDFDocumento4 páginasSign On Letter Opposing HJRes42 - Drug Testing Unemployment Insurance Ap PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- DebunkingGatewayMyth NY 0 PDFDocumento5 páginasDebunkingGatewayMyth NY 0 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Psilocybin Mushrooms FactsSheet Final PDFDocumento5 páginasPsilocybin Mushrooms FactsSheet Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- New Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & CommunitiesDocumento1 páginaNew Solutions Campaign: Promoting Fair & Effective Criminal Justice - Strengthening Families & Communitieswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Psilocybin Mushrooms FactsSheet Final PDFDocumento5 páginasPsilocybin Mushrooms FactsSheet Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- NewSolutionsMarijuanaReformRegulationWorksFinal PDFDocumento1 páginaNewSolutionsMarijuanaReformRegulationWorksFinal PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (1)

- NewSolutionsMarijuanaReformExecSummaryFinal PDFDocumento1 páginaNewSolutionsMarijuanaReformExecSummaryFinal PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- NewSolutionsMarijuanaReformArrestandConvictionConsequencesFinal PDFDocumento1 páginaNewSolutionsMarijuanaReformArrestandConvictionConsequencesFinal PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- LSD Facts Sheet PDFDocumento5 páginasLSD Facts Sheet PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- CA Marijuana Infractions PDFDocumento2 páginasCA Marijuana Infractions PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- LSD Facts Sheet - Final PDFDocumento5 páginasLSD Facts Sheet - Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.org100% (1)

- DPA Ally Fall 2016 v2 PDFDocumento4 páginasDPA Ally Fall 2016 v2 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Safer - Partying - Pocket - Guide - 2016 PDFDocumento16 páginasSafer - Partying - Pocket - Guide - 2016 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- NF DPA California Incarcerations Report 2016 FINAL PDFDocumento11 páginasNF DPA California Incarcerations Report 2016 FINAL PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- California Marijuana Arrest Report August 2016 PDFDocumento3 páginasCalifornia Marijuana Arrest Report August 2016 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- ILRC Report Prop64 Final PDFDocumento37 páginasILRC Report Prop64 Final PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- CA Marijuana Infractions PDFDocumento2 páginasCA Marijuana Infractions PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Toronto Needle Exchange LocationsDocumento4 páginasToronto Needle Exchange LocationsvnstirlingAinda não há avaliações

- BESOKKKDocumento5 páginasBESOKKKpt. maha rendra utamaAinda não há avaliações

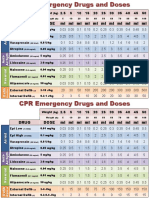

- Emergency DrugsDocumento2 páginasEmergency DrugsCote ParejaAinda não há avaliações

- Sedative HypnoticsDocumento41 páginasSedative HypnoticsPatrick Juacalla100% (2)

- Label TabletDocumento9 páginasLabel TabletDedeh MahmudahAinda não há avaliações

- Antihistamine - WikipediaDocumento39 páginasAntihistamine - WikipediaMuhammadafif SholehuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Neurotransmitters and Drugs ChartDocumento6 páginasNeurotransmitters and Drugs ChartTammy Tam100% (5)

- Nurul Safitri - 1802050210 - 5B Farmasi (Contoh Gol Obat)Documento3 páginasNurul Safitri - 1802050210 - 5B Farmasi (Contoh Gol Obat)Nurul safitriAinda não há avaliações

- Karakteristik Dan Pola Penggunaan Obat Analgesik Nsaid Pada Pasien Pasca Operasi Di Rsud Abdul Wahab Sjahranie SamarindaDocumento11 páginasKarakteristik Dan Pola Penggunaan Obat Analgesik Nsaid Pada Pasien Pasca Operasi Di Rsud Abdul Wahab Sjahranie SamarindaAgung WsbAinda não há avaliações

- Adrenergic Drug MNsDocumento37 páginasAdrenergic Drug MNsTakale BuloAinda não há avaliações

- Comprehensive Drug Education and Vice Control - 075640Documento46 páginasComprehensive Drug Education and Vice Control - 075640Gerome DariaAinda não há avaliações

- Drug AwarenessDocumento5 páginasDrug AwarenessMecs NidAinda não há avaliações

- ONDANSETRONDocumento1 páginaONDANSETRONJugen Gumba Fuentes Alquizar0% (1)

- Introduction To Drugs and The Neuroscience of Behavior 1st Edition Adam Prus Test Bank DownloadDocumento12 páginasIntroduction To Drugs and The Neuroscience of Behavior 1st Edition Adam Prus Test Bank DownloadBonnie Garza100% (23)

- AD - Daftar Produk - 27 Mei 2021Documento11 páginasAD - Daftar Produk - 27 Mei 2021adhimaswicaksono1991Ainda não há avaliações

- Article4Archives32021 3509Documento7 páginasArticle4Archives32021 3509Slobodna DalmacijaAinda não há avaliações

- AntihistaminesDocumento4 páginasAntihistaminessharvabhasin0% (1)

- Controlled Substances ActDocumento17 páginasControlled Substances ActBin WangAinda não há avaliações

- NDPS Act 1985Documento46 páginasNDPS Act 1985nitin aggarwal80% (5)

- Can Ambien Cause AmnesiaDocumento4 páginasCan Ambien Cause Amnesiaark6of7Ainda não há avaliações

- Drug AwarenessDocumento17 páginasDrug AwarenessWinsley RazAinda não há avaliações

- Drug SuffixesDocumento3 páginasDrug SuffixesjeromeasuncionAinda não há avaliações

- Order CITO 04.08.2022Documento8 páginasOrder CITO 04.08.2022lintiaAinda não há avaliações

- Extra Pyramidal Symptoms AdvanceDocumento5 páginasExtra Pyramidal Symptoms AdvanceMr. Psycho Sam100% (1)

- Fentanyl Drug StudyDocumento3 páginasFentanyl Drug StudyAngelica shane Navarro75% (4)

- Amitriptyline 10mg Used For - Google SearchDocumento1 páginaAmitriptyline 10mg Used For - Google Searchks limAinda não há avaliações

- Drug List 1: Over-The - Counter (OTC) MedicationsDocumento3 páginasDrug List 1: Over-The - Counter (OTC) MedicationsAeron GayadanAinda não há avaliações

- Prescription Writing: Esha Ann FransonDocumento9 páginasPrescription Writing: Esha Ann FransonAlosious JohnAinda não há avaliações

- Premedication: Moderator: DR - Dinesh Kaushal Presentsd By: DR Rajesh Raman & DR Gopal SinghDocumento60 páginasPremedication: Moderator: DR - Dinesh Kaushal Presentsd By: DR Rajesh Raman & DR Gopal Singhramanrajesh83Ainda não há avaliações

- NCLEX PsychiatryDocumento55 páginasNCLEX PsychiatryYaoling WenAinda não há avaliações