Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding

Enviado por

Banyu علي تقويم BiruDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding

Enviado por

Banyu علي تقويم BiruDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Griffiths

10.1177/0890334404266976

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding?

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding?

D. Mervyn Griffiths, MCh, FRCS

Abstract

This study assessed indications for and safety and outcome of simple division of tongue tie

without an anesthetic. There were 215 infants younger than 3 months (mean 0-19 days) who

had major problems breastfeeding, despite professional support. Symptoms, tongue tie details, safety of division, and complications were recorded. Feeding was assessed by the mothers immediately, at 24 hours, and 3 months after division. Prior to division, 88% had difficulty

latching, 77% of mothers experienced nipple trauma, and 72% had a continuous feeding cycle. During division, 18% slept throughout; 60% cried more after division (mean 0-15 seconds). There were no significant complications. Within 24 hours, 80% were feeding better.

Overall, 64% breastfed for at least 3 months (UK national average is 30%). Initial assessment,

diagnosis, and help, followed by division and subsequent support by a qualified lactation consultant, might ensure that even more mothers and infants benefit from breastfeeding. J Hum

Lact. 20(4): 409-414.

Keywords: infant, tongue tie, ankyloglossia, frenulum, frenotomy, pediatric surgery,

lactation consultant, breastfeeding

Historically, tongue ties were thought to affect breast1-4

feeding and were thus divided. Today, many current

textbooks and articles state that tongue ties rarely, if

ever, impede feeding or speech, but this assertion is not

5-12

evidence based. There is, however, a group of more

recent, mostly anecdotal articles that once again suggest

that tongue ties may affect breastfeeding in some

13-23

infants. A global campaign, the Baby-Friendly Hos24,25

pital Initiative, has produced renewed interest in this

question, as tongue ties might be a readily treatable

cause of failure to breastfeed.

Before the turn of the century, frenotomies were routinely performed whenever it was found that tongue tie

hindered breastfeeding:

Received for review July 3, 2003; revised manuscript accepted for publication March 23, 2004.

D. Mervyn Griffiths is a general neonatal and pediatric surgeon who has

been dividing tongue ties in children since 1983 and in infants since 1998.

The author would like to thank Carolyn Westcott and Monica Hogan, lactation consultants; Dr Mark Beattie; and Mr David Burge for reading this article

and for their helpful suggestions. Address correspondence to D. Mervyn

Griffiths, Wessex Regional Centre for Paediatric Surgery, Room EG 240,

Southampton General Hospital, SO16 6YD, United Kingdom.

No reported competing interests.

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

DOI: 10.1177/0890334404266976

Copyright 2004 International Lactation Consultant Association

A childs being tongue-tied will impede and hinder his sucking freely. . . . He may be observed to

lose his hold very often. . . . The mouth must be

examined and the tongue set at liberty by cutting a

ligament or string which will be found to confine

the tongue down to the lower part of the mouth and

which is done by the surgeon with little or no pain

to the child who will commonly take to the breast

immediately after the operation without any

inconvenience to him and there never is any danger to be apprehended from bleeding or any other

consequence of the operation.4

When it became apparent that these infants could

usually bottle-feed successfully, division for feeding

problems became unnecessary and was not medically

recommended. After World War II, most UK children

were bottle-fed on National Dried Milk, so fewer had

problems breastfeeding; thus, most of the medical and

nursing literature stated that tongue ties did not impede

26-28

With the realization that breastfeedbreastfeeding.

ing confers many advantages,29-31 there is an increased

expectation that mothers will breastfeed. Although

many infants with tongue ties can breastfeed satisfactorily, those who cannot breastfeed are not referred for division, as most health care providers in the United Kingdom currently believe that tongue ties do not cause

409

410

Griffiths

problems feeding. Consequently, these mothers and

infants must stop breastfeeding and bottle-feed instead.

Only 2 prospective studies (n = 36 and n = 137,

respectively) specifically assessed the issue of whether

failure to breastfeed in an infant with a tongue tie can be

18,22

Both articles advocated

helped by simple division.

division in symptomatic infants. The authors of the

22

larger study divided the tongue tie at 2 to 3 days of age

(at a time when specialist lactation consultant input

might have been enough) and followed the infants for

only 3 days.

To randomize children with symptoms that are not

generally thought to be because of the tongue tie is difficult. Therefore, the author decided to perform a nonrandomized, prospective study to assess the indications

for, and safety and outcome of, tongue tie division at

one center.

Methods

This study assessed the indications for, and safety

and outcome of, simple division of tongue tie without an

anesthetic. All infants whose tongue ties were divided

between December 1999 and December 2001 (N = 519)

were screened for inclusion in the study. Mothers of eligible infants were recontacted at 24 hours and at 3

months after division. Eligibility criteria were infant

younger than 3 months with a tongue tie and mother

wanting to breastfeed but experiencing difficulty doing

so despite professional support.

Definitions

The thickness of the tie was gauged by eye as diaphanous (transparent), medium (nontransparent), or thick

(chunky). The term heart shaped was used (often spontaneously by parents) to describe the shape of the

tongue when the infant attempted protrusion because

the edges of the tongue curled up. A flat anterior edge of

the tongue was referred to as dimpled. The percentage

of tongue tie was also gauged by eye, ranging from 25%

(ie, extending 25% of the distance along the underside

of the tongue) to 100% (ie, to the tip).

Outpatient Division

The infants tongue ties were divided via standard

18,21

The

outpatient surgery performed by the author.

infant was separated from the parents and wrapped

securely in a towel. The infants shoulders were firmly

held by the palms of an assistants hands whose wrists

fixed the infants head. Most older infants disliked

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

being restrained and began to fret. The author put the

tongue tie on the stretch with his left index finger while

holding the lower lip clear with his left thumb. The tie

was divided completely with sharp, blunt-ended, sterile

scissors, and the floor of the mouth was compressed

with a paper towel or gauze square. The infant was

promptly unwrapped, cuddled, and immediately taken

to the mother to be fed, either on the breast or by bottle if

the nipples were too sore. (Lactation consultant input

was not usually available but could be helpful at this

point.) The paper towel could then be used as a bib, if

necessary. No anesthetic or analgesic was used. The

assistant, not the author, measured the length of any crying. Any bleeding was assessed. The mother and baby

fed for as long as they wanted and went home.

The author phoned the study mothers at 24 hours and

at 3 months after division to inquire about breastfeeding

status and any complications. The mother herself was

the only arbiter of whether breastfeeding had improved,

as she is the only person who is able to assess the efficiency of the latch, the pain of chomping on her nipple,

or any improvement in the feeding and sleeping cycle.

All of the study procedures were standard clinical practice, thus the study was deemed exempt from requiring

additional consent.

Results

Of the 519 screened infants, 364 were younger than 3

months at the time of the procedure. Of those, 59 breastfed well prior to division, 57 gave up breastfeeding prior

to division, and 33 never breastfed. Thus, the study

group comprised 215 infants younger than 3 months

who experienced difficulty breastfeeding but whose

mothers said they still wanted to breastfeed if possible.

All 215 mother-infant pairs had been given support by a

midwife, health visitor, infant feeding advisor, or lactation consultant but, despite such professional support,

continued to experience problems with latching, sore

nipples, and continuous feeding. Of the 215 infants, the

mean age was 19 days, and the male-female ratio was

2:1. Forty-four percent had a family history of tongue

tie. Overall, 111 had tried bottle-feedingeither

expressed breast milk (n = 104) or formula (n = 7)of

whom 85 (76%) had found it easy.

Predivision Tongue Tie Parameters

There was no correlation between predivision

frenulum thickness, shape, or percentage tie with the

percentage breastfeeding at 3 months after division. All

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding?

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

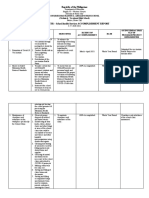

Table 1. Tongue Tie Parameters (N = 215)

Thickness

Diaphanous

Medium

Thick

Shape

Dimple

Heart

Pointed

Percentage of tongue

anchored by tissue

100

75

50

25

Overall

No. (%)

Breastfed for More

Than 3 Months:

No. (%)*

138 (64)

59 (27)

20 (9)

88 (64)

37 (63)

14 (70)

112 (52)

88 (41)

17 (7)

69 (62)

60 (68)

10 (64)

124 (57)

54 (25)

26 (12)

11 (5)

215 (100)

79 (64)

37 (68)

17 (65)

5 (45)

138 (64)

*The data in this column indicate number of mothers in the first column who

breastfed for more than 3 months.

11 infants with tongue ties of 25% had major symptoms

suggestive of a symptomatic tongue tie (8/11 had all 3

symptoms), and 5 of 11 (45%) subsequently breastfed

for 3 months (Table 1).

Indications for Division

Prior to division, 192 of the 215 infants (88%) had

difficulty in latching on to the breast; 167 of their mothers (77%) had painful, sore, or bleeding nipples; and

156 (72%) had a continuous feeding cycle (ie, the

infant fed inefficiently, became tired and fell asleep, but

was still hungry, so slept only for a short time before

waking to feed inefficiently again). Overall, 112

mother-infant pairs (52%) experienced all 3 symptoms;

104 mothers (48%) were expressing and cup- or bottlefeeding, as breastfeeding was too painful and inefficient, although they were keen to restart breastfeeding.

Ninety-five (44%) had tried a nipple shield with professional guidance, and this had helped in 39 (41%) of the

cases (18% overall).

Safety and Complications

During the procedure, 39 infants (18%) remained

asleep. A further 48 (22%) did not cry or their predivision cry persisted unchanged. Furthermore, 128

(60%) had an increased cry after division; of these, 56

(44%) cried for 5 seconds or less. Overall, 183 infants

(85%) cried for 20 seconds or less (overall mean, 15 seconds; median, 10 seconds). Two infants (1%) cried for

more than 1 minute.

411

There were 84 infants (38%) who experienced no

bleeding at all, 113 (52%) produced only a few drops of

blood, and 18 (9%) had a small amount (enough

2

blood to stain the paper towel over an area of 6.25 cm [1

2

in ]). None required as much as 1 minute of pressure,

and there was no delayed primary or secondary hemorrhage. Simple compression of the floor of the mouth

while cuddling the infant during the transfer back to the

mother was usually more than enough to stop the

bleeding.

Four infants had an ulcer under the tongue for more

than 48 hours; all 4 healed spontaneously, and 2 breastfed for 3 months. There were no infections, bleeding

problems, feeding problems, or serious complications

such as damage to the tongue or submandibular ducts.

Overall, 6 infants (3%) had a mild complication (ie, 4

ulcers lasting more than 48 hours, 1 sore for more

than 24 hours, and 1 brown posset due to swallowed

blood).

Feeding Postdivision

In all, 123 mothers (57%) noticed a difference immediately, of whom 83 (70%) breastfed for 3 months, and

92 (43%) felt no immediate difference; however, this

included the 39 infants who remained asleep throughout. Of the remaining 53 mothers of awake infants, 32

(60%) breastfed for 3 months. There were 173 infants

(80%) who were feeding better by maternal assessment

at 24 hours. For 40 (19%), the feeds were unchanged.

Two had increased difficulty feeding.

Three Months Postdivision

(Infants Aged 3 to 6 Months)

Of 215, 138 (64%) breastfed for at least 3 months

after division. Eleven (5%) breastfed for 6 to 12 weeks

after division, whereas 68 (32%) fed for less than 6

weeks. Seventy-two (37%) had not started solids yet, as

they were too young. Two children (1%) were described

as awful feeders on breast, bottle, and with solids.

None of the others experienced feeding problems with

bottles or solids when relevant.

Tongue Extension

Overall, 204 infants (95%) could poke out their

tongues at 3 months. Four could not, of whom 2 breastfed for 3 months. (Data on this outcome were missing

for 7 infants.)

412

Griffiths

Discussion

This prospective study of infants with tongue ties and

breastfeeding problems has revealed no significant

complications with pain, bleeding, or wound healing

and has demonstrated that 64% breastfed for at least 3

months after division.

At presentation, 3 common symptoms were associated with breastfeeding problems caused by a tongue

tie: latching on, nipple trauma, and continuous feeding.

During breastfeeding, the nipple becomes elongated, up

to 3 times its normal size, and stretches back to the junction of the hard and soft palate. The lactiferous sinuses

32

are massaged by the tongue and lower alveolar ridge.

If the tongue is tethered, the nipple is squeezed by the

upper and lower gums (chomp). This is inefficient, is

traumatic, can be very painful, and does not allow normal breastfeeding to occur. Both mother and baby

become increasingly frustrated, and formula feeding

often results. Some mothers try expressing and cup- and

bottle-feeding or use a nipple shield. Careful repositioning with lactation consultant input allows some mothers

to breastfeed adequately. Sometimes, the new position

is very unusual (eg, holding the infant vertically

upright).

Despite a willingness in this unit to divide the tongue

tie as early as possible to allow breastfeeding to continue, the mean age of division was 19 days. On one

hand, this age reflects late referral and difficulty in

scheduling a timely appointment during the week, as

most mother-infant pairs experienced symptoms from

much earlier. On the other hand, later referral allowed

the mother and baby to have time with a health care professional to try many alternatives to division, to allow

them to breastfeed if at all possible. Division at delivery,

for example, would include many infants who breastfeed perfectly satisfactorily and should not be

advocated.

Half of the mother-infant pairs experienced all 3

symptoms. Some mothers were in such pain that they

were willing their babies not to wake up for the next

feed, as they dreaded feeding so much, and subsequently felt very guilty. Overall, 104 (48%) expressed

milk so that their babies could still have the benefits of

breast milk, as breastfeeding itself was impossible.

Forty-one percent of those who tried a nipple shield

found it useful because feeding (although initially

tricky) was pain free. Two mothers continued with the

shield for several months after division, as the infants

preferred it.

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

The thickness, shape, and percentage length of the

tongue tie were not predictors of success or failure. It

would be expected that infants with 100% ties would be

more likely to be successful after division than those

with 25% ties, but this was not found. In addition, 25%

to 75% tongue ties caused problems, as did the 100%

tongue ties. This suggested that the function of the

tongue (ie, the symptoms themselves) produced by a

combination of the tongue, mouth, and tongue tie, is

more important than simply the appearance of the tie.

Common sense suggests that tongue tie division

might be painful and cause bleeding. None of these

infants had any analgesia (Paracetamol elixir or

sucrose) or local anesthetic. Despite this, 39 (18%) slept

throughout. Of the rest, 22% never cried, and although

60% did cry more after division, 85% overall had

stopped within 20 seconds of division. This requires

briskly unwrapping the infant, cuddling him or her in

the crook of ones arm, holding the paper towel on the

floor of the mouth, and promptly returning the infant to

the mother and transferring the infant to the breast or

21

bottle for an immediate feed. Only 2 infants cried for

more than 1 minute. From this, we can surmise that if

division is uncomfortable, the discomfort lasts only for

a few seconds. To put this pain or discomfort in

context, many parents of older infants spontaneously

commented that division was much less painful and

traumatic than immunization, and several junior doctors

and nurses noticed that division was far less traumatic

than intravenous cannula insertion.

Experience using local anesthetic suggests that

infants bleed more from injected local anesthetic than

from the division itself. In addition, safely and accurately injecting the small volumes of local anesthetic

required into the correct place carries a significant risk

of intravenous injection. These factors have to be

weighed against an objective, measured mean length of

crying of 15 seconds.

Of the 131 infants (61%) who experienced any bleeding at all, 113 (52%) produced no more than a few drops

of blood, and the remaining 18 (9%) produced only a

small amount requiring pressure from the finger on

which the infant was sucking.

Regardless of the way the infant was feeding immediately or at 24 hours after division, 64% breastfed for at

least 3 months after division; this is more than the

national average for England and Wales of 30%.33

Breastfeeding for 3 months could not be predicted from

the initial feeding pattern after division, as some infants

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

Do Tongue Ties Affect Breastfeeding?

who experienced miracle cures were started on

bottle-feeding at 6 weeks for maternal convenience, and

some mothers who had preexisting cracked nipples and

were still struggling at 24 hours healed and breastfed for

3 months. When the infants could latch properly and

feed efficiently and painlessly, the mothers and infants

were delighted.

There were no significant complications. The literature has suggested hemorrhage and damage to the

tongue or submandibular gland orifices as possible

27

major complications, but these were not seen. Following division, a white patch under the tongue is normal

for 48 hours. In 4 infants, this took longer to heal but did

not affect long-term outcome. Although failure to poke

out your tongue is not a medically serious symptom, the

parents were delighted that almost all the infants (95%)

were able to do this, often within 24 hours.

This is the largest prospective study yet reported and

has demonstrated that there is a group of infants younger than 3 months who not only have tongue tie but have

an identifiable group of symptoms (poor latch, nipple

trauma, and continuous feeding) that prevented them

from breastfeeding. The infants and mothers were all

given help and support by their midwives, health visitors, infant feeding advisors, or lactation consultants but

were still unable to breastfeed. Following division of the

tongue tie as an outpatient without an anesthetic, with

minimal distress, and with no significant complications,

64% were able to breastfeed for at least 3 months.

If these tongue ties were to be divided by a trained,

accredited, suitably qualified lactation consultant, there

would be less delay, as well as skilled immediate and

long-term support for the mother and child. This would

ensure that an even higher percentage of infants breastfeed, with all the advantages this confers. This practice

has been successfully instituted in our hospital but

raises legal and ethical issues about the scope of lactation consultant practice, which differs between the

United Kingdom and the United States.

Now that this symptomatic subgroup of infants with

tongue ties has been identified, a randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue tie in infants who are

having difficulty breastfeeding is in progress. Objective

measurements of any change in feeding pattern (eg, a

linear analog scale of maternal pain and a relaxed baby

feeding score) need to be developed.

2.

References

30.

1.

Cullum IM. An old wives tale. Br Med J. 1959;2:497-498.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

413

Eminent Physician. The Nurses Guide or the Right Method of Bringing

Up Young Children. 1729. Cited by: Cullum IM. An old wives tale. Br

Med J. 1959;2:497-498.

Pechey J. A General Treatise of the Diseases of Infants and Children.

London; 1697:91-93. Cited by: Cullum IM. An old wives tale. Br Med

J. 1959;2:497-498.

Moss W. An Essay on the Management, Nursing and Diseases of Children. 2nd ed. London; 1794. Cited by: Cullum IM. An old wives tale.

Br Med J. 1959;2:497-498.

Mackinlay GA, Watson ACH. Surgical pediatrics. In: Campbell AGM,

McIntosh N, eds. Forfar and Arneils Textbook of Pediatrics. 5th ed.

Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:1784.

Boon AW. Eyes, ENT and common emergencies. In: Bellman M, Kennedy N, eds. Paediatrics and Child Health. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:270.

Rennie JM, Gandy GM. Examination of the newborn. In: Rennie JM,

Roberton NRC, eds. Textbook of Neonatology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh,

Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:275.

Messner AH, Lalakea ML, Aby J, Macmahon J, Bair E. Ankyloglossia:

incidence and associated feeding difficulties. Arch Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg. 2000;126:36-39.

Messner AH, Lalakea ML. Ankyloglossia: controversies in management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;54:123-131.

Kern I. Tongue-tie. Med J Aust. 1991;155:33-34.

Wright JE. Tongue-tie. J Paediatr Child Health. 1995;31:276-278.

Phillips V. Correcting faulty suck: tongue protrusion and the breast fed

infant. Med J Aust. 1992;156:508.

Browne D. Tongue-tie. Br Med J. 1959;2:952.

Nicholson WL. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) associated with breastfeeding problems. J Hum Lact. 1991;7:82-84.

Berg KL. Two cases of tongue-tie and breastfeeding. J Hum Lact.

1990;6:124-126.

Marmet C, Shell E, Marmet R. Neonatal frenotomy may be necessary

to correct breastfeeding problems. J Hum Lact. 1990;6:117-121.

Berg KL. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) and breastfeeding: a review. J

Hum Lact. 1990;6:109-112.

Masaitis NS, Kaempf JW. Developing a frenotomy policy at one medical centre: a case study approach. J Hum Lact. 1996;12:229-232.

Notestine GE. The importance of the identification of ankyloglossia

(short lingual frenulum) as a cause of breastfeeding problems. J Hum

Lact. 1990;6:113-115.

OShea M. Licking the problem of tongue-tie. Br J Midwifery.

2002;10:90-92.

Jain E. Tongue-tie: its impact on breastfeeding. AARN News Lett.

1995;51:18.

Ballard JL, Auer CE, Khoury JC. Ankyloglossia: assessment, incidence and effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics.

2002;110:e63.

Fernando C. Tongue-Tie, From Confusion to Clarity. Sydney, Australia: Tandem; 1998.

UNICEF. Towards a National Breastfeeding Policy. London, England:

UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative; 1997.

World Health Organization. Evidence for the 10 Steps to Successful

Breastfeeding. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;

1998.

Hussey HH. Editorial: tongue-tie. JAMA. 1974;228:735.

Catlin FI, de Haan V. Tongue-tie. Arch Otolaryngol. 1971;94:548-557.

Wallace AF. Tongue-tie. Lancet. 1963;2:377-378.

American Academy of Pediatrics Working Group on Breast Feeding.

Breastfeeding and the role of human milk. Pediatrics. 1997;6:10351039.

Singhal A, Cole TJ, Lucas A. Early nutrition in pre-term infants and

later blood pressure: 2 cohorts after randomised trials. Lancet.

2001;357:413-419.

414

Griffiths

31. Beral V. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative re-analysis of

individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50,302 women with breast cancer and 96,973 women without

the disease. Lancet. 2002;360:187-195.

32. Woolridge MW. The anatomy of infant sucking. Midwifery.

1986;2:164-171.

33. Hamlyn B, Brooker S, Oleinikova K, Wands S. Infant Feeding 2000.

Norwich, England: Her Majestys Stationary Office; 2002.

Resumen

Es que el frenillo afecta la lactancia materna?

Este estudio evala las indicaciones, seguridad y

resultado de una simple reseccin del frenillo sin

anestesia. Doscientos cincuenta bebes de menos de 3

meses (0=19 das) tenan problemas de lactancia, a

pesar del apoyo profesional. Se registraron sntomas de

frenillo, seguridad de la reseccin y complicaciones.

J Hum Lact 20(4), 2004

Las madres evaluaron la mamada inmediatamente a las

24 horas y a los 3 meses de la reseccin. Antes de la

reseccin, 88% tenan dificultad para agarrar el pecho,

77% de las madres experimentaron trauma del pezn y

72% observaron ciclos continuos de alimentacin.

Durante la reseccin, 18% se quedaron dormidos; 60%

lloraron ms despus de la reseccin (0=15 segundos).

No se vieron complicaciones significativas. En las

primeras 24 horas, 80% estaban lactando mejor. En general, 64% amamantaron al menos 3 meses (el promedio

nacional en el Reino Unido es de 30%). Una evaluacin

inicial, diagnostico y ayuda, seguida por una reseccin

y apoyo por una consultora de lactancia calificada

puede asegurar a que las madres y sus bebes se

beneficien de la lactancia materna.

Você também pode gostar

- Dental Health in Children Born Very Preterm.: Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing January 2004Documento4 páginasDental Health in Children Born Very Preterm.: Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing January 2004Banyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Effects of Preterm Birth On Oral Growth and Development: W. Kim Seow, MDSC, DDSC, PHD, FracdsDocumento7 páginasEffects of Preterm Birth On Oral Growth and Development: W. Kim Seow, MDSC, DDSC, PHD, FracdsBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Superior Labial Frenulum in Newborns: What Is Normal?Documento6 páginasThe Superior Labial Frenulum in Newborns: What Is Normal?Banyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- A Review of The Eruption of Primary Teeth: Chchu, C Y YeungDocumento6 páginasA Review of The Eruption of Primary Teeth: Chchu, C Y YeungBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada 1519-0501Documento13 páginasPesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada 1519-0501Banyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence of Dental Caries and Caries-Related Risk Factors in Premature and Term ChildrenDocumento7 páginasPrevalence of Dental Caries and Caries-Related Risk Factors in Premature and Term ChildrenBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Paulsson2019 Article TheImpactOfPrematureBirthOnDenDocumento7 páginasPaulsson2019 Article TheImpactOfPrematureBirthOnDenBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Effect of Breast Feeding On Eruption of First Primary Tooth in A Group of 6-12 Month Saudi ChildrenDocumento6 páginasThe Effect of Breast Feeding On Eruption of First Primary Tooth in A Group of 6-12 Month Saudi ChildrenBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Effect of Developmental Milestones On Patterns of Teeth EruptionDocumento4 páginasEffect of Developmental Milestones On Patterns of Teeth EruptionBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Effects of Green Tea On Periodontal Health: A Prospective Clinical StudyDocumento7 páginasEffects of Green Tea On Periodontal Health: A Prospective Clinical StudyBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Brunilda Dhamo PHD ThesisDocumento200 páginasBrunilda Dhamo PHD ThesisBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Tooth Eruption Disorders Associated With Systemic and Genetic Diseases: Clinical GuideDocumento16 páginasTooth Eruption Disorders Associated With Systemic and Genetic Diseases: Clinical GuideBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Folayan2010 Article BreastfeedingTimingAndNumberOfDocumento4 páginasFolayan2010 Article BreastfeedingTimingAndNumberOfBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- G Infantoralhealthcare PDFDocumento5 páginasG Infantoralhealthcare PDFBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Mock Up in DentistryDocumento15 páginasMock Up in DentistryBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Surat RiskesdasDocumento2 páginasSurat RiskesdasBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To PedodonticsDocumento29 páginasIntroduction To PedodonticsBanyu علي تقويم Biru100% (1)

- JurnalDocumento5 páginasJurnalBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- PBL BookletDocumento28 páginasPBL BookletBanyu علي تقويم BiruAinda não há avaliações

- FGHF Regenerative DentistryDocumento178 páginasFGHF Regenerative DentistrybuzatugeorgescuAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Use of The Glidescope For Double-Lumen Endobronchial IntubationDocumento3 páginasUse of The Glidescope For Double-Lumen Endobronchial IntubationStephanus Kinshy Imanuel PangailaAinda não há avaliações

- OT101 Philippine HistoryDocumento3 páginasOT101 Philippine HistoryKean Debert SaladagaAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Massage Therapy On Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Pediatric CancerDocumento7 páginasThe Effect of Massage Therapy On Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting in Pediatric CancerAgito Dedi100% (2)

- Duopharma Biotech (DBB MK) : MalaysiaDocumento16 páginasDuopharma Biotech (DBB MK) : MalaysiaFong Kah YanAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- E Health AssessmentDocumento9 páginasE Health AssessmentarisAinda não há avaliações

- Massage Therapy Lafayette PDFDocumento2 páginasMassage Therapy Lafayette PDFPolAinda não há avaliações

- Quality of Life of Patients With Hypertension in Primary Health Care in Bandar LampungDocumento7 páginasQuality of Life of Patients With Hypertension in Primary Health Care in Bandar Lampungwidya astutyloloAinda não há avaliações

- End-of-Life Choices: CPR & DNR WHEN PATIENT & FAMILY CONFLICT OVER DECISION: Ethical Considerations For The Competent PatientDocumento41 páginasEnd-of-Life Choices: CPR & DNR WHEN PATIENT & FAMILY CONFLICT OVER DECISION: Ethical Considerations For The Competent PatientDr. Liza ManaloAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Community Ati e BookDocumento112 páginasCommunity Ati e BookCohort Six100% (2)

- Gluten Free Diet Study On Celiac DiseaseDocumento9 páginasGluten Free Diet Study On Celiac DiseaseJahson WillnotloseAinda não há avaliações

- June 2008 Board Exam QuestionsDocumento25 páginasJune 2008 Board Exam QuestionslaehaaaAinda não há avaliações

- CBAhi-Quality Management & Patient SafetyDocumento14 páginasCBAhi-Quality Management & Patient SafetyJery JsAinda não há avaliações

- E P N M (Mhgap) : Saint Tonis College, IncDocumento11 páginasE P N M (Mhgap) : Saint Tonis College, IncDivine MacaibaAinda não há avaliações

- Informed Consent Assessment Form (UPMREB)Documento3 páginasInformed Consent Assessment Form (UPMREB)Joanna CaytonAinda não há avaliações

- Form Nbte - ND StatisticsDocumento50 páginasForm Nbte - ND StatisticsFidelis GodwinAinda não há avaliações

- Resume - FinalDocumento1 páginaResume - Finalapi-612454288Ainda não há avaliações

- M.S. Ramaiah Dental CollegeDocumento13 páginasM.S. Ramaiah Dental CollegeRakeshKumar1987Ainda não há avaliações

- NPI NCMH StephDocumento12 páginasNPI NCMH StephAnonymous 2fUBWme6wAinda não há avaliações

- MBA-Thesis-Marketing Thesis-Marketing Strategy of An International Publication House: Particular Reference To Internet MarketingDocumento7 páginasMBA-Thesis-Marketing Thesis-Marketing Strategy of An International Publication House: Particular Reference To Internet MarketingAdwait DeAinda não há avaliações

- Sun Pharma Initiating Coverage Report - AMSECDocumento38 páginasSun Pharma Initiating Coverage Report - AMSECkbn errAinda não há avaliações

- Development of COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING in IndiaDocumento12 páginasDevelopment of COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING in IndiaKapil Verma100% (3)

- RPT PolicyDocumento2 páginasRPT PolicyGhulam HaiderAinda não há avaliações

- Fundamentals Exam 3Documento2 páginasFundamentals Exam 3JackieAinda não há avaliações

- 2nd Quarter - School Health Services Accomplishment ReportDocumento4 páginas2nd Quarter - School Health Services Accomplishment ReportJimmellee EllenAinda não há avaliações

- Daiana Deliman: This Is To Certify ThatDocumento2 páginasDaiana Deliman: This Is To Certify ThatDayanna CosminaAinda não há avaliações

- Running Head: Group Dynamics and Organizational Barriers: Name: Course: Tutor: Date of SubmissionDocumento7 páginasRunning Head: Group Dynamics and Organizational Barriers: Name: Course: Tutor: Date of SubmissionjoeAinda não há avaliações

- Heal-Lom A Proposed PJG Hospital Extension in Talavera, Nueva EcijaDocumento10 páginasHeal-Lom A Proposed PJG Hospital Extension in Talavera, Nueva EcijaPhilip PinedaAinda não há avaliações

- Senior Citizen's Act 2010 RA 9994: Alman-Najar Namla XU-College of Law Zamboanga Social Legislation and Agrarian ReformDocumento15 páginasSenior Citizen's Act 2010 RA 9994: Alman-Najar Namla XU-College of Law Zamboanga Social Legislation and Agrarian ReformlazylawstudentAinda não há avaliações

- Test Bank For Tappans Handbook of Massage Therapy 6th Edition by BenjaminDocumento36 páginasTest Bank For Tappans Handbook of Massage Therapy 6th Edition by Benjaminsublunardisbench.2jz85100% (39)

- RMP RXDocumento5 páginasRMP RXGloria RamosAinda não há avaliações

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipNo EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (1135)

- Forever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellNo EverandForever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellAinda não há avaliações