Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Word Music, LLC Et Al v. Priddis Music, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 16

Enviado por

Justia.comTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Word Music, LLC Et Al v. Priddis Music, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 16

Enviado por

Justia.comDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

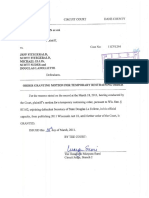

Word Music, LLC et al v. Priddis Music, Inc. et al Doc.

16

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal

Circuit

04-1266

ELECTRONICS FOR IMAGING, INC.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

JAN R. COYLE and KOLBET LABS,

Defendants-Appellees.

William C. Rooklidge, Howrey Simon Arnold & White, LLP, of Irvine, California,

argued for plaintiff-appellant. With him on the brief were Russell B. Hill and Tom

Crunk.

James D. Boyle, Santoro, Driggs, Walch, Kearney, Johnson & Thompson, of Las

Vegas, Nevada, argued for defendants-appellees. With him on the brief was

Steven A. Gibson.

Appealed from: United States District Court for the Northern District of California

JudgeMartinJenkins

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

04-1266

ELECTRONICS FOR IMAGING, INC.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

JAN R. COYLE and KOLBET LABS,

Defendants-Appellees.

__________________________

DECIDED: January 5, 2005

__________________________

Before LOURIE, RADER, and GAJARSA, Circuit Judges.

LOURIE, Circuit Judge.

Electronics for Imaging, Inc. (“EFI”) appeals from the decision of the district court

granting a motion to dismiss its lawsuit against Jan R. Coyle and Kolbet Labs

under the Declaratory Judgment Act (“the Act”). Elecs. for Imaging, Inc. v. Coyle,

No. C 01-4853 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 13, 2003) (“Dismissal Order”). Because the district

court erred as a matter of law and hence abused its discretion, we reverse and

remand.

BACKGROUND

EFI is a company that specializes in network printing solutions, particularly print

controllers. It sells its products to companies such as Canon, Hewlett-Packard,

and Xerox, who in turn incorporate EFI’s technology into their own print servers,

printers, and copiers. EFI is a Delaware corporation with its principal place of

business in Foster

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 1 of 7

Dockets.Justia.com

City, California. Jan Coyle, a Nevada resident, is a listed inventor on U.S.

1

Patents 6,337,746 and 6,618,157, both directed to printing technology. Kolbet

Labs is a Nevada sole proprietorship owned by Daniel Kolbet, who is also a

Nevada resident and an inventor listed on both patents.

Coyle first contacted EFI in September 1997, offering to license his technology,

which was still in development and not yet the subject of an issued U.S. patent.

Subsequently, Coyle and EFI met in Nevada under a non-disclosure agreement.

EFI left that meeting uninterested in Coyle’s work and did not retain any written

information from it. It was not until 1999 that the two parties convened again,

apparently at the request of EFI. According to EFI, its inquiry to Coyle was made

in light of Coyle’s statements concerning progress on the technology and a

pending patent application; Coyle also mentioned his own history of filing patent

infringement lawsuits against such corporations as Atari, Nintendo, Sega, and

NEC Technologies. (Decl. of James L. Etheridge ¶ 2.) In April 2000, the two

parties met under a new non-disclosure agreement to discuss possible licensing

arrangements, but those talks also ended without any agreement.

In June 2001, Coyle discovered certain EFI sales and marketing information that

convinced him that EFI was manufacturing products that were within the scope of

Coyle’s patent application, then still pending. In September 2001, Coyle notified

EFI that the United States Patent and Trademark Office would soon issue

Coyle’s patent, and he asserted that his patent would cover all of EFI’s print

controllers. EFI claims that

1

J & L Electronics, LLC (“J & L”) is a separate business entity created by Jan

Coyle and was assigned title to the ’746 patent. J & L has independently filed suit

against EFI on two separate occasions. See infra note 2.

04-1266 2

during the week of November 26, 2001, Coyle began to pressure EFI on an

almost daily basis, threatening to drive EFI out of business. EFI alleges that

Coyle repeatedly warned that he would bring multiple lawsuits, stating that “we’ll

sue all of your customers” and “bad things are going to happen.” (Compl. ¶ 18.)

Coyle even identified specific attorneys and law firms in support of his litigation

2

threats. Id.

EFI’s general counsel traveled to Nevada on December 5, 2001 to negotiate

terms of an agreement by which EFI could purchase or license Coyle’s

technology. In the course of the discussions, Coyle stated that “I will sue you and

I will fight” and that “all hell w[ill] break loose, I will fight until the end . . . .”

Dismissal Order, slip op. at 5. Additionally, Coyle purportedly gave EFI an

ultimatum, warning that December 15 was the deadline to pay (“If we don’t get a

deal, we will pull the trigger and execute the litigation,” (Compl. ¶ 19)), but

negotiations between the two parties again broke down. On December 11, 2001,

EFI sued Coyle and Kolbet Labs in the United States District Court for the

Northern District of California, seeking a declaratory judgment that EFI did not

breach the two non-disclosure agreements and that EFI did not misappropriate

Coyle’s trade secrets.

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 2 of 7

2

The present case is only one of several suits pending between EFI and Coyle,

Kolbet Labs, and J & L. J & L filed a patent infringement suit against EFI in the

District of Nevada in February 2002, which was dismissed for lack of personal

jurisdiction. In February 2004, we affirmed, without opinion, the district court’s

decision in the Nevada case. J & L Elecs., LLC v. Elecs. for Imaging, Inc., 87

Fed. Appx. 753 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

Also in February 2004, EFI filed a second action in the Northern District of

California, seeking declaratory relief with respect to Coyle’s ’157 patent. That

patent issued on September 9, 2003 from a continuation of the application from

which the ’746 patent originated. Presently, the second California suit is still

pending.

Finally, J & L sued EFI in the District of Arizona in May 2004. That case is also

pending.

04-1266 3

On January 8, 2002, Coyle’s ’746 patent issued, and EFI amended its complaint

that same day to assert noninfringement and invalidity of the patent. Later that

month, Coyle filed motions to dismiss the complaint for lack of personal

jurisdiction, for improper venue, and for failure to comport with the objectives of

the Declaratory Judgment Act. In March 2002, the court granted Coyle’s motion

to dismiss specifically for lack of personal jurisdiction, but it reserved judgment on

Coyle’s other motions to dismiss.

In August 2003, a panel of this court reversed the district court’s dismissal and

remanded the case to the district court. Elecs. for Imaging, Inc. v. Coyle, 340

F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 2003). We determined that the district court erred by

applying Ninth Circuit law on personal jurisdiction to the patent invalidity claim.

Instead, we applied Federal Circuit law, concluding that Coyle had not shown

that the case was “one of the ‘rare’ situations in which sufficient minimum

contacts exist but where the exercise of jurisdiction would be unreasonable.” Id.

at 1352.

In February 2004, on remand, the district court considered the other grounds for

dismissal previously raised by Coyle. The court determined that EFI did not have

any uncertainty about Coyle’s intention to sue because Coyle had provided EFI

with specific deadlines for reaching an agreement, which deadlines had not yet

been met. Dismissal Order, slip op. at 4-5. Additionally, the court found that EFI

was not uncertain about the strength of its legal position. Id. The court thus

decided that EFI’s declaratory suit did not serve the objectives of the Act and was

merely anticipatory, designed to preempt Coyle’s suit and to secure EFI’s own

choice of forum instead. Id. at 6-7. Ultimately, the court granted Coyle’s motion to

dismiss the complaint for failure to comport with the

04-1266 4

objectives of the Act and did not reach the remaining issues (e.g., motion to

dismiss or transfer for improper venue and motion to transfer for convenience).

Id. at 1. EFI timely appealed; we have jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §

1295(a)(1).

DISCUSSION

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 3 of 7

The sole issue now before us is whether the district court properly dismissed

EFI’s lawsuit under the Declaratory Judgment Act. The decision to stay or

dismiss a declaratory action is reviewed for an abuse of discretion, Wilton v.

Seven Falls Co., 515 U.S. 277, 289 (1995), which occurs when: “(1) the court’s

decision was clearly unreasonable, arbitrary, or fanciful; (2) the decision was

based on an erroneous conclusion of law; (3) the court’s findings were clearly

erroneous; or (4) the record contains no evidence upon which the court rationally

could have based its decision,” Minn. Mining & Mfg. Co. v. Norton Co., 929 F.2d

670, 673 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

A declaratory action allows a party “who is reasonably at legal risk because of an

unresolved dispute, to obtain judicial resolution of that dispute without having to

await the commencement of legal action by the other side.” BP Chems. Ltd. v.

Union Carbide Corp., 4 F.3d 975, 977 (Fed. Cir. 1993). The Declaratory

Judgment Act provides that:

In a case of actual controversy within its jurisdiction, . . . any court of

the United States, upon the filing of an appropriate pleading, may

declare the rights and other legal relations of any interested party

seeking such declaration, whether or not further relief is or could be

sought. Any such declaration shall have the force and effect of a

final judgment or decree and shall be reviewable as such.

28 U.S.C. § 2201(a) (2000).

The district court is not required to exercise declaratory judgment jurisdiction, but

has “unique and substantial discretion” to decline that jurisdiction. Wilton, 515

U.S. at 286; EMC Corp. v. Norand Corp., 89 F.3d 807, 810 (Fed. Cir. 1996). The

use of

04-1266 5

discretion is not plenary, however, for “[t]here must be well-founded reasons for

declining to entertain a declaratory judgment action.” Capo, Inc. v. Dioptics Med.

Prods., 387 F.3d 1352, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2004); see also Genentech v. Eli Lilly &

Co., 998 F.2d 931, 937 (Fed. Cir. 1993) (“When there is an actual controversy

and a declaratory judgment would settle the legal relations in dispute and afford

relief from uncertainty or insecurity, in the usual circumstance the declaratory

judgment is not subject to dismissal.”); cf. BP Chems., 4 F.3d at 981 (“A court

may decline to exercise declaratory judgment jurisdiction if it would not afford

relief from the uncertainty, insecurity, and controversy giving rise to the

proceeding.”).

Federal courts must act “in accordance with the purposes of the Declaratory

Judgment Act and the principles of sound judicial administration” when declining

jurisdiction in declaratory suits. EMC Corp., 89 F.3d at 813-14. The question

whether to accept or decline jurisdiction in an action for a declaration of patent

rights in view of a later-filed suit for patent infringement impacts this court’s

mandate to promote national uniformity in patent practice. Because it is an issue

that falls within our exclusive subject matter jurisdiction, we do not defer to the

procedural rules of the regional circuits nor are we bound by their decisions.

Serco Servs. Co., L.P. v. Kelley Co., Inc., 51 F.3d 1037, 1038 (Fed. Cir. 1995);

Genentech, 998 F.2d at 937.

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 4 of 7

A. EFI’s “Uncertainty”

On appeal, EFI argues that the district court incorrectly determined that EFI’s suit

against Coyle and Kolbet Labs would not serve the objectives of the Declaratory

Judgment Act. Particularly, EFI assigns error to the court’s conclusion that

because EFI was confident in its legal position, EFI had no “uncertainty” of the

type contemplated by

04-1266 6

the Act. Instead, EFI asserts that the district court should have focused on the

uncertainty created by Coyle’s persistent and forceful threats of patent

infringement against EFI.

Coyle responds by arguing that the district court properly rejected EFI’s argument

regarding uncertainty in the context of the Act. He claims that because EFI had

assured itself that Coyle’s claims of patent infringement were, in EFI’s view,

meritless, EFI had no ultimate uncertainty regarding its liability to Coyle. Coyle

avers that because EFI was, in fact, “certain” of its rights following an

investigation of Coyle’s claims, EFI’s suit did not serve the purposes of the Act

and EFI thus had no basis upon which it could properly file a declaratory action.

We agree with EFI that the district court erred as a matter of law when it held that

EFI suffered no uncertainty of the kind recognized by the Declaratory Judgment

Act. We have stated that “the purpose of the Declaratory Judgment Act . . . in

patent cases is to provide the allegedly infringing party relief from uncertainty and

delay regarding its legal rights.” Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Releasomers,

Inc., 824 F.2d 953, 956 (Fed. Cir. 1987). The very scenario that EFI faced was a

motivation for enacting the Act, as we have stated in the past:

[A] patent owner . . . attempts extra-judicial patent enforcement with

scare-the-customer-and-run tactics that infect the competitive

environment of the business community with uncertainty and

insecurity. . . . Before the Act, competitors victimized by that tactic

were rendered helpless and immobile so long as the patent owner

refused to grasp the nettle and sue. After the Act, those competitors

were no longer restricted to an in terrorem choice between the

incurrence of a growing potential liability for patent infringement and

abandonment of their enterprises; they could clear the air by suing

for a judgment that would settle the conflict of interests.

04-1266 7

Arrowhead Indus. Water, Inc. v. Ecolochem, Inc., 846 F.2d 731, 735 (Fed. Cir.

1988) (citation omitted).

Here, the district court misinterpreted the term “uncertainty” in the context of the

Declaratory Judgment Act. The proper inquiry should not have been whether a

party is “certain” that its legal position and defense theories are sound, because

litigation is rarely “certain,” even if one is confident of one’s position. When a

party is threatened as EFI has been, there are other uncertainties, including

whether there will be legal proceedings at all, not just whether one will prevail.

There is the uncertainty whether one will have to incur the expense and

inconvenience of litigation, and how it will affect the threatened party’s

customers, suppliers, and shareholders. Reservation of funds for potential

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 5 of 7

damages may be necessary. If “certainty” in one’s position were to preclude

invocation of the Act, then the Act would fail to achieve its purpose of promoting

resolution of disputes, as parties threatened with unjustified litigation, even if they

are “certain” that they will prevail, must incur other uncertainties. When

threatened, they are therefore entitled to sue to bring an end to the threat,

despite their confidence in their position. “Uncertainty” in the context of the Act

refers to the reasonable apprehension created by a patentee’s threats and the

looming specter of litigation that results from those threats. See Minn. Mining,

929 F.2d at 673. Those uncertainties were surely present here, and they were

created by Coyle.

In Minnesota Mining, which is instructive on this point, the Norton Company

threatened 3M and its customers with allegations of patent infringement.

Meanwhile, 3M continued to sell products that it believed did not infringe. As a

result, in that case, despite confidence in its noninfringement position, 3M’s

potential liability grew with each

04-1266 8

sale. Id. at 673-74. We recognized that 3M’s situation was the quandary that the

Act was designed to alleviate and stated: “In promulgating the Declaratory

Judgment Act, Congress intended to prevent avoidable damages from being

incurred by a person uncertain of his rights and threatened with damage by

delayed adjudication.” Id. at 673.

Likewise, in the present case, EFI may in fact be confident that it would

eventually prevail in a patent infringement action. Indeed, Coyle has identified

communications between EFI and its counsel that indicated confidence in their

invalidity defense against Coyle’s “meritless” allegations. Nevertheless, Coyle’s

forceful threats created a cloud over EFI’s business, shareholders, and

customers, and EFI’s potential liability increased as it continued to sell the

allegedly infringing products. EFI is entitled under the Declaratory Judgment Act

to seek a timely resolution of Coyle’s threats of litigation and remove itself from

“the shadow of threatened infringement litigation.” Serco Servs., 51 F.3d at 1038.

The fact that Coyle had stated a deadline for negotiations to be concluded, and

that that deadline had not passed when EFI brought suit, does not deprive EFI of

the right to sue. Given that Coyle had a record of threatening suit in such clear

and descriptive language without always following through promptly on those

threats, EFI was not required to await suit by Coyle. It was entitled to bring the

matter to a head and have it resolved in court.

B. Anticipatory Suit

EFI also argues that the district court abused its discretion by finding that EFI’s

declaratory action was filed in anticipation of Coyle’s impending suit, and that

such a filing justified dismissal. EFI asserts that the district court inaccurately

described the filing of its suit as prompting a “race to the courthouse.” Coyle

responds that the district

04-1266 9

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 6 of 7

court properly concluded that EFI’s suit was anticipatory because EFI knew that

Coyle’s suit was imminent.

We agree with EFI that the district court abused its discretion in its dismissal

order by focusing on the anticipatory nature of the suit. We apply the general rule

favoring the forum of the first-filed case, “unless considerations of judicial and

litigant economy, and the just and effective disposition of disputes, requires

otherwise.” Genentech, 998 F.2d at 938; see Serco Servs., 51 F.3d. at 1039.

“Exceptions . . . are not rare,” but we have explained that “[t]here must . . . be

sound reason that would make it unjust or inefficient to continue the first-filed

action.” Genentech, 998 F.2d at 937-38.

While it is true that a district court may consider whether a party intended to

preempt another’s infringement suit when ruling on the dismissal of a declaratory

action, Serco Servs., 51 F.3d. at 1040, we have endorsed that as merely one

factor in the analysis. Other factors include “the convenience and availability of

witnesses, or absence of jurisdiction over all necessary or desirable parties, or

the possibility of consolidation with related litigation, or considerations relating to

the real party in interest.” Genentech, 998 F.2d at 938. “The considerations

affecting transfer to or dismissal in favor of another forum do not change simply

because the first-filed action is a declaratory action.” Id. No such “other factors”

have been cited here.

In Genentech, we reversed the district court’s dismissal of a declaratory action,

as it was premised solely on the fact that the suit was designed to anticipate a

later-filed complaint in another forum. Id. On the other hand, in Serco Services,

the district court dismissed Serco’s declaratory action as anticipatory, but did so

in view of other factors,

04-1266 10

including the location of witnesses and documents. Serco Servs., 51 F.3d at

1039-40. We affirmed the dismissal in Serco Services because the district court

did not rely solely on the anticipatory nature of Serco’s declaratory action. Id. at

1040.

Here, the facts are more similar to those in Genentech and are distinguishable

from those in Serco Services. As we have determined that the district court’s

reliance on EFI’s lack of uncertainty in its legal position was erroneous, and no

other compelling factors have been cited, the court’s decision is left to rest

exclusively on the alleged anticipatory nature of EFI’s suit. Our precedent,

however, favors the first-to-file rule in the absence of circumstances making it

“unjust or inefficient” to permit a first-filed action to proceed to judgment, and, as

indicated, no such circumstances have been shown here.

The district court’s order dismissing EFI’s suit as anticipatory and contrary to the

purposes of the Declaratory Judgment Act was thus an abuse of discretion.

CONCLUSION

The district court abused its discretion by dismissing EFI’s suit against Coyle,

and we therefore reverse the court’s dismissal and remand for further

proceedings consistent with this opinion.

REVERSED AND REMANDED

04-1266 11

Case 3:07-cv-00502 Document 16 Filed 06/01/2007 Page 7 of 7

Você também pode gostar

- Motion To Dismiss With PrejudiceDocumento90 páginasMotion To Dismiss With PrejudiceJusticeForAmericans87% (39)

- Admin Law 1 Sources of Administrative Law in ZambiaDocumento7 páginasAdmin Law 1 Sources of Administrative Law in ZambiaRichard Mutachila75% (4)

- Motion To Quash or Modify Subpoena and Motion To Dismiss 11 24714 CA 22Documento15 páginasMotion To Quash or Modify Subpoena and Motion To Dismiss 11 24714 CA 22whoisjohndoes100% (1)

- Defamation ComplaintDocumento12 páginasDefamation ComplaintChristopher Stoller ED100% (6)

- Final Corrected Copy Federal SuitDocumento43 páginasFinal Corrected Copy Federal SuitSilenceIsOppression100% (1)

- HCA No 170 of 2002 (Rentry)Documento23 páginasHCA No 170 of 2002 (Rentry)Keith SpencerAinda não há avaliações

- State Pay ScaleDocumento135 páginasState Pay Scalejames alexanderAinda não há avaliações

- Family Law in Zambia - Chapter 10 - AdoptionDocumento8 páginasFamily Law in Zambia - Chapter 10 - AdoptionZoe The PoetAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocumento13 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- UnpublishedDocumento15 páginasUnpublishedScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Koyle v. Sand Canyon Corporation, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento20 páginasKoyle v. Sand Canyon Corporation, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Bowers, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento25 páginasUnited States v. Bowers, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Business Law CasesDocumento23 páginasBusiness Law Cases2810247Ainda não há avaliações

- UnpublishedDocumento23 páginasUnpublishedScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- BizProLink LLC v. America Online Inc, 4th Cir. (2005)Documento12 páginasBizProLink LLC v. America Online Inc, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Iraola & Cia, S.A., Plaintiff-Counter-Defendant-Appellant v. Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Defendant-Counter-Claimant-Appellee, Geo Med, N.A., J.N. Anderson, George Semones, 325 F.3d 1274, 11th Cir. (2003)Documento15 páginasIraola & Cia, S.A., Plaintiff-Counter-Defendant-Appellant v. Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Defendant-Counter-Claimant-Appellee, Geo Med, N.A., J.N. Anderson, George Semones, 325 F.3d 1274, 11th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Order Granting Defendant'S Motion To Dismiss First Amended Complaint (Re: Docket No. 66)Documento8 páginasOrder Granting Defendant'S Motion To Dismiss First Amended Complaint (Re: Docket No. 66)Eric GoldmanAinda não há avaliações

- 14a0265n 06Documento17 páginas14a0265n 06daniel.dixon2396Ainda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocumento9 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocumento25 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocumento35 páginasPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Joel S. ABEL, v. AMERICAN ART ANALOG, INC. and Michael D. Zellman and Philip Cohen. Appeal of AMERICAN ART ANALOG, INC. and Philip CohenDocumento10 páginasJoel S. ABEL, v. AMERICAN ART ANALOG, INC. and Michael D. Zellman and Philip Cohen. Appeal of AMERICAN ART ANALOG, INC. and Philip CohenScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Anna Knoll and Rose Keller v. Socony Mobil Oil Company, Inc., A Corporation, 369 F.2d 425, 10th Cir. (1966)Documento9 páginasAnna Knoll and Rose Keller v. Socony Mobil Oil Company, Inc., A Corporation, 369 F.2d 425, 10th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Order On Defendants' Motion To Dismiss Second Amended ComplaintDocumento30 páginasOrder On Defendants' Motion To Dismiss Second Amended ComplaintReality Check 1776Ainda não há avaliações

- George Everette Sibley, Jr. v. Grantt Culliver, 377 F.3d 1196, 11th Cir. (2004)Documento16 páginasGeorge Everette Sibley, Jr. v. Grantt Culliver, 377 F.3d 1196, 11th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals For The Eleventh CircuitDocumento23 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals For The Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- 29 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 396, 29 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 32,877 Robert Jones v. Lumberjack Meats, Inc., A Corporation, 680 F.2d 98, 11th Cir. (1982)Documento5 páginas29 Fair Empl - Prac.cas. 396, 29 Empl. Prac. Dec. P 32,877 Robert Jones v. Lumberjack Meats, Inc., A Corporation, 680 F.2d 98, 11th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Call of The Wild Howell Troll Decision 5-12-11Documento21 páginasCall of The Wild Howell Troll Decision 5-12-11Kenan FarrellAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento25 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- A Thinking Ape v. Lodsys GroupDocumento15 páginasA Thinking Ape v. Lodsys GroupPriorSmartAinda não há avaliações

- In Re Bees, 562 F.3d 284, 4th Cir. (2009)Documento9 páginasIn Re Bees, 562 F.3d 284, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocumento6 páginasFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Fed. Sec. L. Rep. P 96,599 Florabelle Coffey v. Dean Witter Reynolds Inc., A Delaware Corporation and Jeffrey Hines, An Individual, 961 F.2d 922, 10th Cir. (1992)Documento9 páginasFed. Sec. L. Rep. P 96,599 Florabelle Coffey v. Dean Witter Reynolds Inc., A Delaware Corporation and Jeffrey Hines, An Individual, 961 F.2d 922, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitDocumento14 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals For The Ninth CircuitFinally Home RescueAinda não há avaliações

- Hoppe OrderDocumento3 páginasHoppe Orderwhittney evansAinda não há avaliações

- 00888-20040310 UMG Memo OpinionDocumento3 páginas00888-20040310 UMG Memo Opinionlegalmatters100% (1)

- Canoy v. Ortiz & Yu v. BondalDocumento2 páginasCanoy v. Ortiz & Yu v. BondalGilbertGalopeAinda não há avaliações

- Billy v. Curry County Board, 10th Cir. (2015)Documento4 páginasBilly v. Curry County Board, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Not PrecedentialDocumento10 páginasNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Judge Keenan's Decision Dismissing Bhopal CaseDocumento36 páginasJudge Keenan's Decision Dismissing Bhopal CaseVihanka NarasimhanAinda não há avaliações

- Ebel v. King, 10th Cir. (2006)Documento5 páginasEbel v. King, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Gov Uscourts Azd 732217 56 0Documento13 páginasGov Uscourts Azd 732217 56 0J DoeAinda não há avaliações

- Altering Copy!!!!!!: (R. "Answer of Def. John L. & Donna Reed", pg.1, para 1)Documento18 páginasAltering Copy!!!!!!: (R. "Answer of Def. John L. & Donna Reed", pg.1, para 1)John ReedAinda não há avaliações

- Cody v. United States, 249 F.3d 47, 1st Cir. (2001)Documento8 páginasCody v. United States, 249 F.3d 47, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Not PrecedentialDocumento14 páginasNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Lorna Lamotte Motion To Dismiss 2ND Amended ComplaintDocumento81 páginasLorna Lamotte Motion To Dismiss 2ND Amended ComplaintSLAVEFATHERAinda não há avaliações

- PrIL DigestsDocumento22 páginasPrIL DigestsKevin HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Reborn Enterprises, Inc. v. Fine Child, Inc., Andrews MacLaren Inc., Andrews MacLaren LTD., Ben's For Kids, Inc., James Fine and Mark Wein, 754 F.2d 1072, 2d Cir. (1985)Documento2 páginasReborn Enterprises, Inc. v. Fine Child, Inc., Andrews MacLaren Inc., Andrews MacLaren LTD., Ben's For Kids, Inc., James Fine and Mark Wein, 754 F.2d 1072, 2d Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Not PrecedentialDocumento4 páginasNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Sre Carlsbad, Inc., Third/party v. Kerr-Mcgee Coal Corporation, Third/party, 56 F.3d 67, 3rd Cir. (1995)Documento3 páginasSre Carlsbad, Inc., Third/party v. Kerr-Mcgee Coal Corporation, Third/party, 56 F.3d 67, 3rd Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocumento16 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Eoi Electronics, Inc., Sai Semispecialists of America, Inc., Plaintiffs v. Xebec, A Corporation, 785 F.2d 391, 2d Cir. (1986)Documento10 páginasEoi Electronics, Inc., Sai Semispecialists of America, Inc., Plaintiffs v. Xebec, A Corporation, 785 F.2d 391, 2d Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals For The Federal CircuitDocumento14 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals For The Federal CircuitpauloverhauserAinda não há avaliações

- America Online Inc v. St. Paul Mercury Ins, 4th Cir. (2003)Documento21 páginasAmerica Online Inc v. St. Paul Mercury Ins, 4th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Oyer, 10th Cir. (2012)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Oyer, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- May 2021 Indiana Appellate Court Re Alfa SubpoenaDocumento11 páginasMay 2021 Indiana Appellate Court Re Alfa SubpoenaFile 411Ainda não há avaliações

- Not PrecedentialDocumento15 páginasNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- TFN V OeyDocumento14 páginasTFN V Oeyinternetcases100% (1)

- CLS Bank Vs Alice CorporationDocumento135 páginasCLS Bank Vs Alice CorporationJames LindonAinda não há avaliações

- In The Common Pleas Court of Erie County, OidoDocumento12 páginasIn The Common Pleas Court of Erie County, OidoFinney Law Firm, LLCAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Alan D. Amon, United States of America v. Gary W. Dunbar, 669 F.2d 1351, 10th Cir. (1982)Documento19 páginasUnited States v. Alan D. Amon, United States of America v. Gary W. Dunbar, 669 F.2d 1351, 10th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Eller v. Trans Union, 10th Cir. (2013)Documento28 páginasEller v. Trans Union, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413No EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413Ainda não há avaliações

- Amended Poker Civil ComplaintDocumento103 páginasAmended Poker Civil ComplaintpokernewsAinda não há avaliações

- U.S. v. TomorrowNow, Inc. - Criminal Copyright Charges Against SAP Subsidiary Over Oracle Software TheftDocumento5 páginasU.S. v. TomorrowNow, Inc. - Criminal Copyright Charges Against SAP Subsidiary Over Oracle Software TheftJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Arbabsiar ComplaintDocumento21 páginasArbabsiar ComplaintUSA TODAYAinda não há avaliações

- Divorced Husband's $48,000 Lawsuit Over Wedding Pics, VideoDocumento12 páginasDivorced Husband's $48,000 Lawsuit Over Wedding Pics, VideoJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- U.S. v. Rajat K. GuptaDocumento22 páginasU.S. v. Rajat K. GuptaDealBook100% (1)

- USPTO Rejection of Casey Anthony Trademark ApplicationDocumento29 páginasUSPTO Rejection of Casey Anthony Trademark ApplicationJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Stipulation: SAP Subsidiary TomorrowNow Pleading Guilty To 12 Criminal Counts Re: Theft of Oracle SoftwareDocumento7 páginasStipulation: SAP Subsidiary TomorrowNow Pleading Guilty To 12 Criminal Counts Re: Theft of Oracle SoftwareJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Emmanuel Ekhator - Nigerian Law Firm Scam IndictmentDocumento22 páginasEmmanuel Ekhator - Nigerian Law Firm Scam IndictmentJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Clergy Abuse Lawsuit Claims Philadelphia Archdiocese Knew About, Covered Up Sex CrimesDocumento22 páginasClergy Abuse Lawsuit Claims Philadelphia Archdiocese Knew About, Covered Up Sex CrimesJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Signed Order On State's Motion For Investigative CostsDocumento8 páginasSigned Order On State's Motion For Investigative CostsKevin ConnollyAinda não há avaliações

- Rabbi Gavriel Bidany's Federal Criminal Misdemeanor Sexual Assault ChargesDocumento3 páginasRabbi Gavriel Bidany's Federal Criminal Misdemeanor Sexual Assault ChargesJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Supreme Court Order Staying TX Death Row Inmate Cleve Foster's ExecutionDocumento1 páginaSupreme Court Order Staying TX Death Row Inmate Cleve Foster's ExecutionJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Deutsche Bank and MortgageIT Unit Sued For Mortgage FraudDocumento48 páginasDeutsche Bank and MortgageIT Unit Sued For Mortgage FraudJustia.com100% (1)

- Brandon Marshall Stabbing by Wife: Domestic Violence Arrest ReportDocumento1 páginaBrandon Marshall Stabbing by Wife: Domestic Violence Arrest ReportJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Van Hollen Complaint For FilingDocumento14 páginasVan Hollen Complaint For FilingHouseBudgetDemsAinda não há avaliações

- Rabbi Gavriel Bidany's Sexual Assault and Groping ChargesDocumento4 páginasRabbi Gavriel Bidany's Sexual Assault and Groping ChargesJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Guilty Verdict: Rabbi Convicted of Sexual AssaultDocumento1 páginaGuilty Verdict: Rabbi Convicted of Sexual AssaultJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Online Poker Indictment - Largest U.S. Internet Poker Cite Operators ChargedDocumento52 páginasOnline Poker Indictment - Largest U.S. Internet Poker Cite Operators ChargedJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Bank Robbery Suspects Allegedly Bragged On FacebookDocumento16 páginasBank Robbery Suspects Allegedly Bragged On FacebookJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Court's TRO Preventing Wisconsin From Enforcing Union Busting LawDocumento1 páginaCourt's TRO Preventing Wisconsin From Enforcing Union Busting LawJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Wisconsin Union Busting LawsuitDocumento48 páginasWisconsin Union Busting LawsuitJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- FBI Records: Col. Sanders (KFC - Kentucky Fried Chicken Founder) 1974 Death ThreatDocumento15 páginasFBI Records: Col. Sanders (KFC - Kentucky Fried Chicken Founder) 1974 Death ThreatJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Sweden V Assange JudgmentDocumento28 páginasSweden V Assange Judgmentpadraig2389Ainda não há avaliações

- Defamation Lawsuit Against Jerry Seinfeld Dismissed by N.Y. Judge - Court OpinionDocumento25 páginasDefamation Lawsuit Against Jerry Seinfeld Dismissed by N.Y. Judge - Court OpinionJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- NY Judge: Tricycle Riding 4 Year-Old Can Be Sued For Allegedly Hitting, Killing 87 Year-OldDocumento6 páginasNY Judge: Tricycle Riding 4 Year-Old Can Be Sued For Allegedly Hitting, Killing 87 Year-OldJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Charges Against Ariz. Shooting Suspect Jared Lee LoughnerDocumento6 páginasFederal Charges Against Ariz. Shooting Suspect Jared Lee LoughnerWBURAinda não há avaliações

- City of Seattle v. Professional Basketball Club LLC - Document No. 36Documento2 páginasCity of Seattle v. Professional Basketball Club LLC - Document No. 36Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- 60 Gadgets in 60 Seconds SLA 2008 June16Documento69 páginas60 Gadgets in 60 Seconds SLA 2008 June16Justia.com100% (10)

- Lee v. Holinka Et Al - Document No. 4Documento2 páginasLee v. Holinka Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.com100% (4)

- OJ Simpson - Nevada Supreme Court Affirms His ConvictionDocumento24 páginasOJ Simpson - Nevada Supreme Court Affirms His ConvictionJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 160889. April 27, 2007. Dr. Milagros L. Cantre, Petitioner, vs. Sps. John David Z. GO and NORA S. GO, RespondentsDocumento13 páginasG.R. No. 160889. April 27, 2007. Dr. Milagros L. Cantre, Petitioner, vs. Sps. John David Z. GO and NORA S. GO, RespondentsRhea Ibañez - IlalimAinda não há avaliações

- Gatchalian vs. DelimDocumento5 páginasGatchalian vs. DelimYong NazAinda não há avaliações

- The Nanny Versus Former Uber Engineer Anthony LevandowskiDocumento81 páginasThe Nanny Versus Former Uber Engineer Anthony LevandowskiTechCrunchAinda não há avaliações

- Quashing DecisionsDocumento127 páginasQuashing DecisionsSunil LodhaAinda não há avaliações

- Aguiar Answer Brief (Fla. 4th DCA)Documento28 páginasAguiar Answer Brief (Fla. 4th DCA)DanielWeingerAinda não há avaliações

- Oblicon - ReviewerDocumento91 páginasOblicon - ReviewerLara De los SantosAinda não há avaliações

- 1979 International Convention Against The Taking of Hostages PDFDocumento8 páginas1979 International Convention Against The Taking of Hostages PDFdanalexandru2Ainda não há avaliações

- Katarungan PDFDocumento16 páginasKatarungan PDFJaymie ValisnoAinda não há avaliações

- Corr. Ad.-ReviewDocumento6 páginasCorr. Ad.-ReviewJen Paez100% (1)

- United States v. Clyde R. Sherrow, JR, 166 F.3d 1206, 3rd Cir. (1998)Documento1 páginaUnited States v. Clyde R. Sherrow, JR, 166 F.3d 1206, 3rd Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digests ObliconDocumento13 páginasCase Digests ObliconKarla Espinosa100% (1)

- SPF Client Compliance Application BG SBLC MTN LTN MonetizationDocumento15 páginasSPF Client Compliance Application BG SBLC MTN LTN MonetizationHugo Rogelio CERROSAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture Notes On Technical English 2Documento20 páginasLecture Notes On Technical English 2Enya Francene GarzotaAinda não há avaliações

- 100 Worst Mistakes in Government ContractsDocumento23 páginas100 Worst Mistakes in Government Contractshenrihaas8677100% (2)

- Desertion As Ground For DivorceDocumento16 páginasDesertion As Ground For DivorceAnkurAinda não há avaliações

- Asli Gyaan Sem 4Documento24 páginasAsli Gyaan Sem 4AASTHA SACHDEVAAinda não há avaliações

- 42nd Amendment Act UPSC NotesDocumento3 páginas42nd Amendment Act UPSC NotesJyotishna MahantaAinda não há avaliações

- Purchase Agreement of Citric Fruits Republic Bolivarian of VenezuelaDocumento2 páginasPurchase Agreement of Citric Fruits Republic Bolivarian of VenezuelaTomasAlbarranAkaTomsAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of Arrest For DrugsDocumento3 páginasAffidavit of Arrest For DrugsMarion Jossette50% (2)

- Law-3 Test BanksDocumento42 páginasLaw-3 Test BanksPatDabz77% (13)

- LegislaturesDocumento89 páginasLegislaturesFoundation IASAinda não há avaliações

- I Specpro DigestsDocumento16 páginasI Specpro DigestsPJ SLSRAinda não há avaliações

- Paper VII Procedural PracticeDocumento2 páginasPaper VII Procedural PracticeAhsan AbroAinda não há avaliações

- Latasa Vs COMELEC Case Digest GUZMANDocumento2 páginasLatasa Vs COMELEC Case Digest GUZMANJohn Soliven100% (1)

- Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Reynaldo PazDocumento4 páginasPhilippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Reynaldo PazCortes Reynaldo AngelitoAinda não há avaliações

- 1st Case Digest - NewDocumento7 páginas1st Case Digest - NewAnonymous NqaBAyAinda não há avaliações