Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Dolls of Hope Author's Note

Enviado por

Candlewick PressDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Dolls of Hope Author's Note

Enviado por

Candlewick PressDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Note from Author

SHIRLEY PARENTEAU

A few years ago, pictures of my little granddaughter dressed in a beautiful kimono led me

to research the Japanese Girls Day festival

called Hinamatsuri, where treasured dolls are

put on display. That research led to the all-but-

forgotten Friendship Dolls project of 1926 and

eventually to my novel Ship of Dolls and to

telling more of the story through the eyes of a

Japanese girl in Dolls of Hope.

In 1926, Dr. Sidney Gulick, a teacher missionary who retired after working in Japan for

thirty years, worried about approaching war

between the two countries he loved. He began the

Friendship Doll project, urging children across

America to send thousands of dolls to children

in Japan in hope of creating friendship between

the two countries. Children in nearly every state

responded. The Blue-Eyed Dolls received an

enthusiastic welcome in Japan, with parties and

ceremonies held throughout the country. Children

there donated money to have fifty-eight large

dolls created by their countrys finest doll makers and dressed in rich kimonos. These, with many

accessories, were sent in gratitude to children in America in time for C

hristmas of 1927.

Sadly, the beautiful hope for friendship expressed by the children of both countries could not

prevent war. With the Japanese bombing of American ships in Pearl Harbor in 1941, America

was drawn into World War II. In both countries, the dolls became symbols of the enemy. The

Japanese government ordered the American dolls to be destroyed. In America, the Japanese dolls

were put into storage and forgotten.

Now, long after WWII, the two countries have healed and become friends. The friendship

project lives on as well, with dolls again sharing the culture of each country.

Bill Gordons website on the Friendship Dolls, www.bill-gordon.net/dolls, provided a major

source of information for the novels, with photos and facts from 1926to today.

Doll maker Hirata Gouyou really lived and created some of the Dolls of Return Gratitude,

including one I have visited in a museum at the University of Nevada in Reno. Hirata Gouyou,

who eventually became one of Japans revered Living Treasures, was a young man of twenty-four

and already a master doll maker in 1927. If Chiyo had been real instead of a fictional character, I believe she would have enjoyed knowing Hirata-san, just as I

have enjoyed giving him an important part in the story.

The value of the Japanese yen has fallen dramatically since WWII. In Chiyos

time, one yen was worth about fifty cents in U.S. money. Chiyos two 10-yen

coins from the mayor of Tokyo were together worth about $10.00in U.S. money.

Of course, prices in 1927were much lower than today, and to Chiyo that amount

was a fortune. She rarely had even a sen, worth about 1/100th the value of one

yen, as a penny is worth 1/100th of a U.S. dollar.

For research on life in rural Japan in 1927, I relied on a fascinating collection

of interviews in the book Memories of Silk and Straw: A Self-Portrait of Small-

Town Japan by Dr. Junichi Saga. And I am indebted to my daughter-in-law,

Miwa, for researching Japanese-language Internet sites for information needed

for the story and for help with cultural descriptions and occasional words in the

Japanese language. Writing Chiyos story has been a challenge, an adventure, and

a joy. Any mistakes that may have slipped through are entirely my own.

SHIRLEY PARENTEAU is the author of many books for young people, including the

historical novel Ship of Dolls, as well as the picture books Bears on Chairs,

Bears in Beds, and Bears in the Bath. About this book, she says, When I

discovered that in 1926 to 27, so many dolls were exchanged between the

United States and Japan, I wondered about the children who took part.

The question prompted Ship of Dolls and Dolls of Hope, the stories of two

girls, half a world apart, who give their hearts to Emily Grace, a doll whose

tumultuous journey ignites unexpected strengths in them both. Shirley Parenteau lives with her

husband in Elk Grove, California.

Illustration 2015 by Kelly Murphy

Você também pode gostar

- By Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and MangaNo EverandBy Your Side: The First 100 Years of Yuri Anime and MangaNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The Hanmoji Handbook Your Guide To The Chinese Language Through Emoji Chapter SamplerDocumento32 páginasThe Hanmoji Handbook Your Guide To The Chinese Language Through Emoji Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press100% (4)

- JourneyPlanet 64 - AlamatDocumento36 páginasJourneyPlanet 64 - AlamatChristopher John GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Bond 11 Plus: 11 Plus English Practice TestDocumento9 páginasBond 11 Plus: 11 Plus English Practice Testthayanthiny100% (1)

- The Bracelet - Yoshiko UchidaDocumento12 páginasThe Bracelet - Yoshiko Uchidacstocksg1100% (1)

- Monsters of The True World - Maztica and LopangoDocumento54 páginasMonsters of The True World - Maztica and LopangoSeethyr88% (8)

- Aquinas and The Three Problems of MusicDocumento19 páginasAquinas and The Three Problems of MusicJohn Brodeur100% (1)

- The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian CultureNo EverandThe Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian CultureNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (8)

- The Book That No One Wanted To Read by Richard Ayoade Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasThe Book That No One Wanted To Read by Richard Ayoade Press ReleaseCandlewick Press0% (1)

- Loki: A Bad God's Guide To Being Good by Louie Stowell Chapter SamplerDocumento48 páginasLoki: A Bad God's Guide To Being Good by Louie Stowell Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press80% (5)

- Become An App Inventor Chapter SamplerDocumento45 páginasBecome An App Inventor Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press50% (2)

- History of Children's LiteratureDocumento19 páginasHistory of Children's LiteratureS. Ma. Elisabeth Ngewi,rvmAinda não há avaliações

- Footnote To YouthDocumento6 páginasFootnote To YouthAvreile Rabena50% (2)

- Test Link BeltDocumento25 páginasTest Link BeltMANUEL CASTILLOAinda não há avaliações

- Sora and The CloudDocumento12 páginasSora and The CloudImmedium100% (1)

- The Last Mapmaker Chapter SamplerDocumento74 páginasThe Last Mapmaker Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press60% (5)

- Sari-Sari Summers by Lynnor Bontigao Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasSari-Sari Summers by Lynnor Bontigao Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- The Infamous Ratsos Live! in Concert! Chapter SamplerDocumento19 páginasThe Infamous Ratsos Live! in Concert! Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Elevated Deer StandDocumento8 páginasElevated Deer StandWill Elsenrath100% (1)

- Anna Hibiscus by Atinuke Chapter SamplerDocumento23 páginasAnna Hibiscus by Atinuke Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press100% (2)

- PE 4 Lesson Recreation and AquaticsDocumento31 páginasPE 4 Lesson Recreation and AquaticsAngelica Manahan75% (8)

- Cress Watercress by Gregory Maguire Chapter SamplerDocumento45 páginasCress Watercress by Gregory Maguire Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- The Wizard in The Wood by Louie Stowell Chapter SamplerDocumento45 páginasThe Wizard in The Wood by Louie Stowell Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- A Dragon Used To Live Here by Annette LeBlanc Cate Chapter SamplerDocumento61 páginasA Dragon Used To Live Here by Annette LeBlanc Cate Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- The Book of Indian Crafts and Indian Lore: The Perfect Guide to Creating Your Own Indian-Style ArtifactsNo EverandThe Book of Indian Crafts and Indian Lore: The Perfect Guide to Creating Your Own Indian-Style ArtifactsAinda não há avaliações

- The Lucky Ones by Linda Williams Jackson Chapter SamplerDocumento64 páginasThe Lucky Ones by Linda Williams Jackson Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press100% (1)

- The Guitar Magazine - April 2019 PDFDocumento148 páginasThe Guitar Magazine - April 2019 PDFWassimAinda não há avaliações

- Fairytale Kingdom: The Story of Little Red Riding HoodDocumento2 páginasFairytale Kingdom: The Story of Little Red Riding HoodArei JeonAinda não há avaliações

- Women in Ukiyo-EDocumento68 páginasWomen in Ukiyo-EtgmuscoAinda não há avaliações

- Consuming Japan: Popular Culture and the Globalizing of 1980s AmericaNo EverandConsuming Japan: Popular Culture and the Globalizing of 1980s AmericaAinda não há avaliações

- Healer and Witch by Nancy Werlin Chapter SamplerDocumento61 páginasHealer and Witch by Nancy Werlin Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Jasmine Green Rescues: A Foal Called Storm Chapter SamplerDocumento29 páginasJasmine Green Rescues: A Foal Called Storm Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Meant To Be by Jo Knowles Chapter SamplerDocumento45 páginasMeant To Be by Jo Knowles Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- McTavish On The Move Chapter SamplerDocumento19 páginasMcTavish On The Move Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Take Off Your Brave: The World Through The Eyes of A Preschool Poet Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasTake Off Your Brave: The World Through The Eyes of A Preschool Poet Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Two-Headed Chicken by Tom Angleberger Author's NoteDocumento1 páginaTwo-Headed Chicken by Tom Angleberger Author's NoteCandlewick Press0% (1)

- Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global ImaginationNo EverandMillennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global ImaginationNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (7)

- Kiyo Sato: From a WWII Japanese Internment Camp to a Life of ServiceNo EverandKiyo Sato: From a WWII Japanese Internment Camp to a Life of ServiceAinda não há avaliações

- The Haiku Apprentice: Memoirs of Writing Poetry in JapanNo EverandThe Haiku Apprentice: Memoirs of Writing Poetry in JapanAinda não há avaliações

- PVR Cinemas Marketing StrategyDocumento64 páginasPVR Cinemas Marketing StrategySatish Singh ॐ92% (26)

- American Grit: From a Japanese American Concentration Camp Rises an American War HeroNo EverandAmerican Grit: From a Japanese American Concentration Camp Rises an American War HeroAinda não há avaliações

- Diva Nation: Female Icons from Japanese Cultural HistoryNo EverandDiva Nation: Female Icons from Japanese Cultural HistoryAinda não há avaliações

- Grimlite: We Live in A Forgotten World. The Company Brought Peace, Then Left. Only The Doomed and The Lost RemainDocumento56 páginasGrimlite: We Live in A Forgotten World. The Company Brought Peace, Then Left. Only The Doomed and The Lost RemainBryan RuheAinda não há avaliações

- Essays on Japan's Lost Decade and Cinema Vol 2: Representation of Gender and PerformanceNo EverandEssays on Japan's Lost Decade and Cinema Vol 2: Representation of Gender and PerformanceAinda não há avaliações

- Graphic Indigeneity: Comics in the Americas and AustralasiaNo EverandGraphic Indigeneity: Comics in the Americas and AustralasiaAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts That Bind Us by Caroline O'Donoghue Chapter SamplerDocumento80 páginasThe Gifts That Bind Us by Caroline O'Donoghue Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- History of Children's Literature GenresDocumento22 páginasHistory of Children's Literature GenresTrisha TrishaAinda não há avaliações

- The Pear Affair by Judith Eagle Chapter SamplerDocumento58 páginasThe Pear Affair by Judith Eagle Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Brand New Boy by David Almond Chapter SamplerDocumento64 páginasBrand New Boy by David Almond Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press50% (2)

- Memoirs of Geisha 2Documento14 páginasMemoirs of Geisha 2Rindon KAinda não há avaliações

- Shanghai Baby: The Adventures of an American Girl from the Far East to the MidwestNo EverandShanghai Baby: The Adventures of an American Girl from the Far East to the MidwestAinda não há avaliações

- M. Giuliani: Serenade Op. 127. I Maestoso. Flute/ViolinDocumento3 páginasM. Giuliani: Serenade Op. 127. I Maestoso. Flute/ViolinnsaribekyanAinda não há avaliações

- Kids Fight Climate Change: Act Now To Be A #2minutesuperhero Chapter SamplerDocumento26 páginasKids Fight Climate Change: Act Now To Be A #2minutesuperhero Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press100% (1)

- Literature Book AnalysisDocumento19 páginasLiterature Book Analysisapi-325255998Ainda não há avaliações

- Hujita SanDocumento23 páginasHujita SanSealAinda não há avaliações

- History of Paper DollsDocumento3 páginasHistory of Paper DollsKlingplatAinda não há avaliações

- Playing with History: American Identities and Children’s Consumer CultureNo EverandPlaying with History: American Identities and Children’s Consumer CultureAinda não há avaliações

- After the Flash: One Woman's Journey from Japan to GI TownNo EverandAfter the Flash: One Woman's Journey from Japan to GI TownAinda não há avaliações

- Japanese LitDocumento6 páginasJapanese LitMariel delos AngelesAinda não há avaliações

- Historical FictionDocumento9 páginasHistorical Fictionapi-298464083Ainda não há avaliações

- Preface To A Japanese TaleDocumento5 páginasPreface To A Japanese TalePriscila Torres ConradoAinda não há avaliações

- Dolls in Japan PDFDocumento31 páginasDolls in Japan PDFRosaargAinda não há avaliações

- Liza Dalby - WikipediaDocumento18 páginasLiza Dalby - WikipediaTelmaMadiaAinda não há avaliações

- A Centennial Celebration of The Brownies’ BookNo EverandA Centennial Celebration of The Brownies’ BookDianne Johnson-FeelingsAinda não há avaliações

- Final Draft EssayDocumento5 páginasFinal Draft Essayapi-252443422Ainda não há avaliações

- How Memoirs of a Geisha Commodified Japanese Culture for Western AudiencesDocumento11 páginasHow Memoirs of a Geisha Commodified Japanese Culture for Western AudiencesAnastasia Krilova-GalkinaAinda não há avaliações

- 20th Century Children BooksDocumento50 páginas20th Century Children BooksStefanny JuarbalAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Bim L A N 7 INGLESDocumento25 páginas2 Bim L A N 7 INGLESblinblinwebboyAinda não há avaliações

- Modern FantasyDocumento22 páginasModern Fantasyapi-301164351Ainda não há avaliações

- Fabricating Consumers: The Sewing Machine in Modern JapanNo EverandFabricating Consumers: The Sewing Machine in Modern JapanNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Empire of Dogs: Canines, Japan, and the Making of the Modern Imperial WorldNo EverandEmpire of Dogs: Canines, Japan, and the Making of the Modern Imperial WorldAinda não há avaliações

- The Barbie PhenomenonDocumento13 páginasThe Barbie PhenomenonAdnanaParpalaAinda não há avaliações

- Kei78569 ch03Documento42 páginasKei78569 ch03Aura MateiuAinda não há avaliações

- The Nightcrawler King: Memoirs of an Art Museum CuratorNo EverandThe Nightcrawler King: Memoirs of an Art Museum CuratorAinda não há avaliações

- Memoirs of A GeishaDocumento6 páginasMemoirs of A GeishaANGELO GABRIEL CAPULONGAinda não há avaliações

- Cinderella StoryDocumento7 páginasCinderella Storyapi-253503213Ainda não há avaliações

- 00Documento38 páginas00Sophia MaramaraAinda não há avaliações

- History of Children's LiteratureDocumento19 páginasHistory of Children's LiteratureKimshen B. Delos SantosAinda não há avaliações

- AFS Monograph 9Documento390 páginasAFS Monograph 9Mariano VázquezAinda não há avaliações

- Anime Guida Al Cinema D Animazione GiapponeseDocumento24 páginasAnime Guida Al Cinema D Animazione GiapponeseCarmela ManieriAinda não há avaliações

- My Bollywood Dream by Avani Dwivedi Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasMy Bollywood Dream by Avani Dwivedi Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Where The Water Takes Us by Alan Barillaro Press ReleaseDocumento3 páginasWhere The Water Takes Us by Alan Barillaro Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- My Dog Just Speaks Spanish by Andrea Cáceres Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasMy Dog Just Speaks Spanish by Andrea Cáceres Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Different For Boys by Patrick Ness Press ReleaseDocumento2 páginasDifferent For Boys by Patrick Ness Press ReleaseCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Different For Boys by Patrick Ness Discussion GuideDocumento3 páginasDifferent For Boys by Patrick Ness Discussion GuideCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Different For Boys by Patrick Ness Discussion GuideDocumento3 páginasDifferent For Boys by Patrick Ness Discussion GuideCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- About The Book: Walker Books Us Discussion GuideDocumento2 páginasAbout The Book: Walker Books Us Discussion GuideCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- I'm A Neutrino: Tiny Particles in A Big Universe Chapter SamplerDocumento8 páginasI'm A Neutrino: Tiny Particles in A Big Universe Chapter SamplerCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Telus Mobility - WikipediaDocumento10 páginasTelus Mobility - WikipediaYohan RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Summer Homework for NurseryDocumento5 páginasSummer Homework for NurseryAnishSahniAinda não há avaliações

- G41C GSDocumento6 páginasG41C GSLe ProfessionistAinda não há avaliações

- MVREGCLEANDocumento54 páginasMVREGCLEANSamir SalomãoAinda não há avaliações

- VDP Technical Drawings RealDocumento12 páginasVDP Technical Drawings Realapi-331456896Ainda não há avaliações

- Birdy Shelter Piano MusicDocumento11 páginasBirdy Shelter Piano MusicClare DawsonAinda não há avaliações

- Sigma Katalog 2013Documento37 páginasSigma Katalog 2013fluidaimaginacionAinda não há avaliações

- Joystick System OperationDocumento3 páginasJoystick System OperationHusi NihaAinda não há avaliações

- Characters of Mamma MiaDocumento2 páginasCharacters of Mamma Miacjdvcanv27Ainda não há avaliações

- Life Pre Int Unit 2 CompetitionsDocumento12 páginasLife Pre Int Unit 2 CompetitionsVioleta UrrutiaAinda não há avaliações

- Congratulating & Complimenting - Print - Quizizz-DigabungkanDocumento5 páginasCongratulating & Complimenting - Print - Quizizz-DigabungkanKhikmatul AmelliaAinda não há avaliações

- "Thought Bubble" - Anime Fanzine Issue 04 - December 2015Documento30 páginas"Thought Bubble" - Anime Fanzine Issue 04 - December 2015Thought Bubble100% (1)

- Related Literature Canistel, (Pouteria Campechiana), Also Called Yellow Sapote, or Eggfruit, Small Tree ofDocumento3 páginasRelated Literature Canistel, (Pouteria Campechiana), Also Called Yellow Sapote, or Eggfruit, Small Tree ofPrincess Hailey Borlaza100% (3)

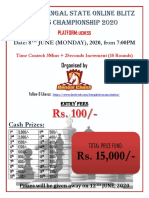

- Bca Online Blitz Brochure Final-2Documento3 páginasBca Online Blitz Brochure Final-2rikAinda não há avaliações

- El Nido Resort Lagen Island InnovationDocumento5 páginasEl Nido Resort Lagen Island InnovationAlessandra Faye BoreroAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Comprehension Level ElementaryDocumento15 páginasReading Comprehension Level ElementarysimoprofAinda não há avaliações

- AH Harris PDFDocumento264 páginasAH Harris PDFJason PowellAinda não há avaliações

- DND 5th Edition Premade - HexlockDocumento4 páginasDND 5th Edition Premade - HexlockVlad DobreAinda não há avaliações

- Heavy Minerals and Magnetic SeparationDocumento5 páginasHeavy Minerals and Magnetic SeparationMaster Geologia UsalAinda não há avaliações