Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Shinder 1978 Early Ottoman Administration

Enviado por

ashakow8849Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Shinder 1978 Early Ottoman Administration

Enviado por

ashakow8849Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness: Some Limits on Comparison

Author(s): Joel Shinder

Source: International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Nov., 1978), pp. 497-517

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/162076

Accessed: 01-08-2015 09:20 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of

Middle East Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Int. J. Middle East Stud. 9 (1978), 497-517

Printed in Great Britain

497

Joel Shinder

EARLY

OTTOMAN

ADMINISTRATION

IN THE WILDERNESS:

LIMITS

SOME

ON COMPARISON

A synthesis of Ottoman administrative history has yet to be written, and it is

unlikely that one will appear in the near future. The task is enormous, and more

glamorous subjects continue to receive priority. Even now the field of administrative history exists largely as an ancillary to the study of Ottoman diplomatic

instruments or as a foundation for the study of the modernization of traditional

society. In the latter case it has fallen under the spell of institutional history,

where three theses and at least one 'antithesis' scurry in their murine way across

the tiles of the Ottoman edifice. Despite the fact that a developed literature is

lacking, specialists in other disciplines have used the Ottoman example for broad

comparative studies of bureaucratic empires.1 Their premature attempts have

perpetuated the notion already endemic in Islamist circles that what we know

of Islamic government is all there is to know and need be known. Several themes,

however, have dominated the study of governing institutions in the Middle East

with a force that has surely impeded progress and fresh thought. Our first results

from the four theses referred to earlier are terribly outdated at worst or in need

of modification at best. New source materials in the Ottoman archives and new

readings of older materials long subject to scholarly scrutiny call for a reexamination of those leading themes and the theses they inspire before any attempt at

synthesis and comparison is made.

The first twentieth-century thesis on Ottoman institutions was advanced by

Alfred Howe Lybyer in his World War I classic, The Governmentof the Ottoman

Empire in the Time of Suleiman the Magnificent, reprinted in New York (1966)

from the 1913 Cambridge, Massachusetts, edition of Harvard University Press.

Lybyer based his research on Western materials, from which he concluded

that the Empire may be understood in terms of two institutions: the Ruling

Institution and the Moslem Institution. The first consisted of the personal slaves

of the sultans, slaves who with few exceptions were the conscripted sons of

Christian parents. In contrast, the Moslem Institution was peopled entirely by

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I wish to acknowledge the support of the National Endowment for

the Humanities and of the State University of New York Research Foundation in the

preparation of this essay. I would also like to thank Harvard University's Center for

Middle Eastern Studies for the facilities made available to me.

1 S. N. Eisenstadt, The Political Systems of Empires (London, 1963), is an example of

the way in which the Ottoman case has been used for comparison and model-building.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 Joel Shinder

freeborn Muslims. Members of the first wielded military and administrative

power, while those of the second were responsible for the maintenance of the

Islamic faith (theology, law, philosophy, and other religious sciences). Whereas

the first group is European, Christian, and 'white,' the second is Asiatic,

Muslim, and 'Turkish.' When the strict separation of these staffs broke down

late in Siileyman's reign, the Empire's fate was sealed.2

Late in the thirties Paul Wittek, a most scrupulous Ottomanist, presented his

famous ghazi thesis in The Rise of the Ottoman Empire and in a Revue des Jtudes

Islamiques articles, 'De la defaite d'Ankara a la prise de Constantinople,' both

appearing in 1938. During the fourteenth and well into the fifteenth centuries,

according to Wittek, the chief tension in the Empire was that between the

independent and 'antinomian' frontier warriors of the faith or ghazis on the

one hand and the orthodox purveyors of a High Islamic, hinterland tradition,

the ulema, on the other. The sultan's authority could be maintained only by

balancing these two elements, whence the devsirme or child levy, at once a

compromise with the ghazi ideal of forced conversion (or death) and a constraint

on ulema pretensions. Ulema success would threaten the raison d'etre of the

state, the Holy War of the ghazis, and bring on decline.

During the sixties Professor Stanford J. Shaw, of the University of California,

Los Angeles, then of Harvard, prepared an unpublished study of the Ottoman

Empire in two parts: 'The Formative Years' and 'Decline and Reform' (available

at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Reading Room).

Shaw observed a tension between the Turkish aristocracy, scions of prominent

Turkoman tribal families, and the devsirmeclass of slave converts together with

their freeborn Muslim sons. With the defeat of the Turkish aristocracy, the

devsirme class split into rival factions temporarily allied with other groups such

as the ulema and harem cliques. The sultan could no longer depend on the

countervailing force of the aristocracy to check the excesses of the victorious if

fragmented devsirme class. Although the aristocracy of the late sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries produced reformist tracts designed to restore to them the

powers usurped by the devsirme,the sultan was either too weak or too dependent

on devsirmemilitary muscle to accept these proposals as the bases for policy. The

aristocracy's military contribution, chiefly cavalry, was simply outmoded.

Artillery and infantry were needed, and these were the devsirme's forte. Shaw's

view, therefore, is a correction to the Lybyer thesis, and it has found a degree

of support recently from the thorough studies of Halil Inalcik.3

2

Lybyer, Government, pp. 36-37, 50. His thesis was developed and refined by H. A. R.

Gibb and Harold Bowen in Islamic Society and the West, Vol. I, Islamic Society in the

Eighteenth Century, Part I (Oxford, I950). I am indebted to Ms. Judith-Ann Corrente of

Harvard University for her comments in a seminar paper, 'Approaches to Ottoman

Institutions: An Historiographical Essay,' which I found helpful in this analysis.

3 Professor Halil Inalcik has an extensive list of publications, the most relevant of which

are the following: 'Ottoman Methods of Conquest,' Studia Islamica, 2 (1954), 103-I30;

'The Emergence of the Ottomans,' in The Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. I (Cambridge,

The Ottoman Empire in the Classical Age 1300-1600

(New York,

I970), pp. 263-295;

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 499

Against these three essentially bipolar theses stands an antithesis, if such it

is, developed variously by Lewis V. Thomas, Norman Itzkowitz, and Halil

Inalcik.4 In contrast with the theses, which are political in emphasis, the antithesis is a cultural or social model of the traditional, High Islamic Near Eastern

state. The model describes a corporate society of Men of the Sword, Men of

the Pen (both making up the Ottoman ruling or askeri class), Men of Negotiation,

and Men of Husbandry (both making up the Ottoman subject class of reaya).

The Men of the Pen in the Ottoman system are then subdivided into the ilmiye

and kalemiye, the careers of religious-legal knowledge (the ulema) and of the

bureaucracy (the kiittab). Ottoman absolutism was founded on Persian traditions

of statecraft modified by Islamic law, solidified by the Turkic tradition of

dynastic succession, which replaced the Islamic theory of election, and effected

by the reign of justice within a circle of equity. This circle has eight propositions:

a state requires a sovereign authority to enforce rational and Holy Law; to have

authority a sovereign must exercise power; to have power and control one needs

a large army; to have an army one needs wealth; to have wealth from taxes one

needs a prosperous people; to have a prosperous subject population one must

have just laws justly enforced; to have laws enforced one needs a state; to have

a state one needs a sovereign authority. Justice is fundamentally the maintenance

of corporate order - keeping the four classes of men and their subdivisions in

place. This is done through the Holy Law of Islam supplemented with if not

complemented by the rational and customary law of the sultanate, kanun. But

the key fiscal and administrative unit for the implementation of order is the

timar or quasi-feudal regime, which is seen as part of the continuing Persian

legacy, through the Abbasids and Seljuks, to the Ottomans. Here the key to

Ottoman studies, then, is not the polarities of the political models. Ottoman

society was too complex. Diversification and stratification, shifting alliances and

alignments within and between occupational classes are what the sociocultural

model emphasizes. Rather than tension between two groups with a central

authority seeking balance, this model suggests the genesis of a ruling elite

drawing membership from and controlling admission to all service areas. It is

clearly more sophisticated than its competitors. All four, however, are ruled by

themes that pervade Islamic studies in the twentieth century.

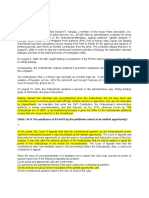

This point may be elucidated through the simple graphic device of the chart,

whose object is to afford the examiner an opportunity to discern the meanings

of symbols A and B. What is the underlying structure of the chart? Or, put

1973). Inalcik, unlike Shaw, prefers to see the 'Turkish Aristocracy' as the march lords

or uc begs and limits the tension between this group and the devsirme party to the period

ca. I362-ca.

600oo. He also works toward a synthesis by incorporating the 'Muslim

Aristocracy' or chief ulema families into his scheme. The effect is to bring Wittek and

Lybyer (as corrected by Shaw) together.

4Thomas, A Study of Naima (New York, 1972);

Itzkowitz, 'Eighteenth Century

Ottoman Realities,' Studia Islamica, 26 (I962), 73-94, and Ottoman Empire and Islamic

Tradition (New York, 1972), and, with Max Mote, Mubadele: An Ottoman-Russian

Exchange of Ambassadors (Chicago, 1970); Inalcik in the works cited in n. 3 above, but

especially in Classical Age.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FOUR

Origin of thesis

THESES

IN

OTTOMAN

I. Lybyer

A (State)

Ruling Institution

2. Wittek

Ghazi (to Devsirme)

3. Shaw/inalcik

Devsirme Party

Devsirme

Kapl Kullarla or

Central Government

4. Inalcik/Itzkowitz/Thomas

Askeri (Rulers)

Men of the Pen

Bureaucracy

Religion/Law

Men of the Sword

Kapi Kullar

Timariots

Auxiliaries

INSTITUTIONAL

HISTORY

Intermediate Status

Miners

Guards (e.g., bridges)

Road crews

Falcon breeders

Sheep breeders, marketers

Persons in the immediateservice of the sultan, whether in the palaceitself or in the provinces

salaried, supported by estates, or in the combination of these two.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 501

another way, what do the symbols 'A' and 'B' stand for, and what is their

thematic foundation? (See chart on facing page.)

One theme in Umayyad and Abbasid history (A.D. 661-750 and 750-I258,

respectively) is the struggle between advocates of centralized and those of

decentralized government. A second popular theme has been the antagonism of

different racial groups in government itself, if not throughout the society. Arabs,

Persians, Kurds, Berbers, Turks, and Circassians figure prominently in the

application of this theme. Yet a third is the rivalry of the military and the

bureaucracy in such states as the Abbasid, Great Seljuk, Mamluk, and Ottoman.

Where these themes have not masked a stark Western ethnocentrism, they have

often served as handmaidens to ideologies past and present, East and West:

nationalism, secularism, Islamic reformism, or Arabism. More specific themes

of the same formulation exist for the Ottoman case: on origins - Byzantine/

European vs. Muslim/Asiatic; on ruling elites - gallant frontiersman vs. effete

hinterlander; on power loci - Palace vs. Porte; on policy - reaction/Islamic

Orthodoxy vs. reform/Westernization; on broad cultural influences - Turkish

romanticism vs. Islamic ecumenicism. It is obvious that these themes as well

have ideological content or potential. The chief problem raised by the examples,

however, is not the advancement of ideology. Their bipolar formulation violates

the principle in logic of the excluded middle. This requires that any ambiguous

statement be either true or false. For example, it is incorrect to ask whether the

Ottoman government was in the hands of free Muslim Turks or of converted

non-Turkish slaves and to expect that one is true, the other false. The correct

question is whether or not the Ottoman government, once clearly defined, was

in the hands of free Muslim Turks, and so forth. Disregard of the principle

creates artificial situations of tension between alternative choices which an

historical society may or may not have faced. It produces loaded or complex

questions of the nature: 'How did you spend the money you stole'?

Although the preceding examples do not immediately degenerate into fallacies,

a principal theme in Islamic history does - a theme that, as is demonstrated, is

the underlying structure of the mystery chart above. This theme is the disruptive

tension between the ideals of the Holy Law of Islam, the shari'a (feriat in

Ottoman usage), and the practical needs of sovereign states. Inquiries based on

the theme conclude from comparisons of Islamic political theory and isolated

examples of actual practice that Islamic governments have consistently failed to

be 'Islamic' and that Islamic society has failed to be 'political.' This succinct

version borders on equivocation, perhaps inevitably in view of the heavily

theoretical bias of the research supporting the theme. The research closes in on

legal theory and executive practice, demanding absolute purity of the first,

corruption of the second:5

Even the most harmoniousco-operationof jurisprudentsand executive officialdom

could not have preventedthe gap between the ideal and the actual, the normativeand

5 GustaveE. von Grunebaum,MedievalIslam:A

Studyin CulturalOrientation,2d ed.

(Chicago, 1956), p. 143.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

502

Joel Shinder

the practical,the precedentof sacred law and the makeshiftdecision of the executive

order, from widening until it became unbridgeable.The pious condemnedthe ruler's

deviationsfrom the establishednorm of the Prophet's days, and in fear for their souls

they evaded his call when he summoned them to take office.

Thus the governmentof Allah and the governmentof the sultan grew apart. Social

and political life was lived on two planes, on one of which happenings would be

spiritually valid but actually unreal, while on the other no validity could ever be

aspiredto. The law of God failed because it neglected the factor of change to which

Allahhad subjectedhis creatures.[Legaltheory]had, unwittinglyperhaps,relinquished

that grandiosedream of a social body operatingperpetuallyunder the immutablelaw

which God had revealedin the fulness of time.

There is an opposition here between government or state and society, and it is

suggested that this is a uniquely Islamic phenomenon despite historical evidence

to the contrary. Because the legists of early Islam wrestled with the problem of

theory and practice for ages bereft of the Prophet's guidance, it is argued, all

subsequent states and societies, in being Islamic, suffered the same difficulty.

This is the fallacy of division, where the properties of the whole are considered

true also for the parts (assuming, of course, the validity of the properties of the

whole as described). The fallacy of composition, where the properties of the

parts are considered true also for the whole, is introduced when certain key

Islamic states, like the Abbasid, are considered models for the entire Islamic

community or umma.

When the full theme is drafted into use for the discussion of Ottoman state

and society, the fallacy of division applies. One consequence of such reasoning

is the judgment that practitioners of Ottoman government, as of any Islamic

government, uniformly displayed a total lack of administrative morality. This

comes from the uncritical reading of a spate of 'government' manuals which can

rival The Prince for the challenge they pose the literary analyst. An eleventhcentury manual urges, 'Commit no forgery for a trivial object, but [reserve it]

for the day when it will be of real service to you and the benefits substantial.'6

Noting evidence of corruption in Ottoman administrative ranks, a thinker of

this ilk - steeped, to be sure, in Oriental lore - would find his general conclusion

exonerated. The abundance of Ottoman manuals which urge probity would not

impress him. A comparative perspective, in other words, has thrown the Ottoman

child into the wilderness where, left to the devices of nature, he would thrive

on the milk of two gray wolves, the beasts of State and Society or, respectively,

symbols A and B in the chart above (p. 500). In terms of the theme, it should be

remembered, 'society' is chiefly the ulema and other popular leadership outside

the framework of the government proper. Recognizing the official status of the

ulema in the Ottoman state, the Inalcik-Itzkowitz-Thomas proposition is more

strictly functional in its askeri-reaya definition.

The Ottoman state should be fully characterized, however, as primarily

Islamic, Turkish, dynastic, monocratic, and agrarian. To the extent that it was

6

Reuben Levy, trans., A Mirror for Princes: The Qdbus Ndma by Kai Kd'uis Ibn

Iskander, Prince of Gurgan (London,

I95I),

p. 209.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 503

Islamic, it enjoyed only some elements of a civilization to which it fell heir, and

it contributed much to that civilization. The same may be said for its Turkic

legacy. In neither case is the legacy full. The dynasty, the monocracy, and the

economy differ vastly from earlier and later forms, Turkish or Islamic. Similarly,

Ottoman administration differs from earlier and later varieties in accordance

with development under unique conditions, particularly those introduced with

the expansion into Europe and, only subsequently, into the Islamic heartlands

of the Middle East, thence into North Africa. These distinctions, unfortunately,

have not been preserved. Identical terms for administrative offices and methods

as between the Ottomans and other Islamic states have been taken for coincidence

and continuity in institutions, regardless of chronological and spatial gaps. To

the shifting of personnel across frontiers has been added a lengthy baggage train

containing the paraphernalia of a paradigmatic and reified 'traditional Near

Eastern State and Society.' The important conclusion is that it is indispensable to

study Ottoman administration for itself and in its own context. The comparative

study of Islamic government is more than a welcome endeavor, provided

that the comparative approach yields results other than mirror images of a selffulfilled prophecy. The remainder of this essay, accordingly, is concerned with

what the past bequeathed to Ottoman administration (to the extent that current

research allows) and how the bequest has been presented in historical writings.

Ideally, this discussion would be followed by an in-depth examination of

Ottoman administration from the reign of Sultan Mehmed II (145I-148I) to

the first third of the eighteenth century, by which time major changes in the

imperial administration had largely run their course. The materials used here,

however, are not drawn from the early period merely to introduce a continuous

survey. Even a cursory review is not possible in the present state of the field.

The chief intention is rather to discuss notions which have affected the study of

Ottoman administration in any period. One such notion, the Turkish ghazi thesis,

has its roots in the first Ottoman chronicles.

An early source hostile to bureaucratic, centralized government introduces

the history of Ottoman central administration with the following story. One

market day in about the year A.D. 1300 a man from the neighboring principality

of Germiyan came to the court of Osman Beg, founder of the Ottoman dynasty

and first of the great ten leaders of that house. The visitor offered to purchase

the tax farm on market tolls. Osman ingenuously asked, 'What is a market toll?'

The Germiyanid explained what market tolls were and, noting the just prince's

ire, advanced his claim by demonstrating the universality of the practice in all

sovereign states since the beginning of time. Yielding to the stranger, who was

supported by the local kadi and military commander, Osman promulgated

regulations known as kanun - executive law - to govern not only market taxes

but also timars, the estates whose usufruct went to the support of warriors and

other servants of the dynasty.7

The tendentiousness of this story is more significant than the content. On one

7

'A?ikpa?azade, Tevdrih-i Al-i Osman, ed. 'Ali (Istanbul, I332/II915), pp.

I9-20.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The

504 Joel Shinder

side is the simple, pure leader of warriors for the faith, whose sole concern is and

should be advancing the frontiers of Islam at the cost of the Christian infidels.

On the other side stand the external forces of the status quo, princes like those

of Germiyan who, together with the Islamic religious establishment (the kadi)

and the entrenched household military commander, prefer stable, regulatory

government to the material sacrifices and disorder of jihad. Outsiders, it is

claimed, sullied the high aims of the Ottoman house, which is identified with

the ghazi movement. The tsar is good, but he is misled by his advisors! The

principal interest of the earliest chronicles as they have come down to us, then,

is the ghazi's exploits against the unbelievers.8 Sophisticated government, whose

Anatolian purveyors were the religious-legal scholars of the ulema class, is

considered the chief hindrance to the ghazi effort. The simplistic, highly

syncretistic and, to some extent, mystical Islam with Shi'i heterodox tendencies

to which the ghazis independently adhered would not tolerate the extensively

developed and institutionalized system of siyisa shar'iya. This was a theoretical

symbiosis of politics and Islamic Holy Law which regulated not only the status

and financial obligations of lands and peoples absorbed into the Abode of Islam

by conquest or surrender, but also the prerogatives and responsibilities of those

in authority.9 According to this doctrine, the two classes of emirs or secular

princes and the ulema are in authority. The first keeps order, and the second

serves as the heir and guardian of the Prophet's path. It is what the ghazis had

presumably rejected in leaving the heartlands of the Islamic Middle East to open

new frontiers in the company of clansmen and confederates. (Never mind the

compulsion to move ever farther westward with the Mongols breathing hard not

far behind.) Interloping strangers from the heartlands with their manners,

customs, and institutions were not wanted even for the sake of legitimizing and

consolidating the recent conquests. Sword, compound bow, and pony were

thought sufficient to that end. More important, the ghazis justifiably felt that the

existence of the timar regime and kanun legislation at this early date is a moot point.

'A?ikpasazade is henceforth referred to as Apz., preceded by the editor's last name.

8 Friedrich Griese, ed., Die altosmanischeChronik (Tevarikh-i Al-i Osman) des 'Aszkpasazdde

Mehmed,

Qift9io/lu,

chronicles

9 Refer

in addition to the 'All and Atsiz editions; Oruc, Karamani

(Leipzig, I929),

$ukrullah, Tursun Beg, Ahmedi, and Ne*ri in several editions (but do see the

N. Atsiz collection, Osmanlh Tarihleri, Vol. I, Istanbul, I949) - the earliest

we know - possibly share a common prototype.

to the discussion of Ibn Taymiya's docrine of siyasa shar'iya in E. I. J. Rosen-

thal, Political Thoughtin Medieval Islam: An IntroductoryOutline (Cambridge, 1958), pp.

58, 6o. It should be noted, however, that even in the small states which were successors

to the Abbasids the doctrine was often ignored in practice, its author having little if any

following. Ira M. Lapidus has demonstrated that in many Syrian and Mesopotamian

towns and cities new elites emerged during periods of upheaval, common from the ninth

century. Military regimes which controlled former Abbasid provinces were incapable of

'reordering' local situations. The urban ulema stepped into the vacuum and, through

intermarriage with merchant, administrative, and landowning families, forged a new

elite defined by religious qualification. This development,

however, should not be

superimposed on the scene in western Asia Minor from the thirteenth century. See 'The

Evolution of Muslim Urban Society,' Comparative Studies in Society and History, 25

(1973), 21I-50, esp. pp. 39-4I.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 505

strangers would divert the resources of the new conquests - that is to say, booty from the hands of the actual victors and put them to use for the benefit of others

through an organized and regular system of taxation.

Unqualified acceptance of this interpretation is risky. In his story of the

market toll, 'Aslkpasazade (1393-1481) left his own imprint on his recension of

the prototypical chronicle. His disapproval of Sultan Mehmed II's administrative policies is clear. Where sultans through Murad II (1421-1451) merely led

or ordered campaigns resulting in conquests, Mehmed II went beyond conquest

and had scribes busily registering and confiscating the booty.10 Bayezid I

(1389-I403) had also committed this 'error' of rapid centralization, but Timur

had put an end to his excesses after the Battle of Ankara (1402) by restoring

local autonomy to Asia Minor dynasts. The evil of bureaucracy itself is attributed

to external (Germiyanid) influences on the pristine form of Ottoman government. Those who perpetuated the evil, the ulema, also come under the author's

fire. The Candarli family of viziers is singled out for having introduced corruption into the world.1 Acting under the influence of their breed of officialdom,

sultans themselves began to accumulate wealth, that sure sign of corruption

resulting in the fall of states and rulers, the destruction of the soldiery, and chaos.

Bayezid I and his personal agents had suffered these very consequences. It is

not only the influence of the ulema, then, which is responsible for disruption.

Part of the blame is also placed on the use of personal agents or slaves, kapt

kullarz.12

'Aslkpasazade's argument is poorly developed. The ghazis were as much

refugee tribal fragments from the east fleeing Mongol advances and seeking new

pastures as they were earnest warriors for Islam occupied more with the future

of their souls. The late fifteenth-century politics of the chronicler must not be

confused with early thirteenth-century realities. The attempt to use the early

chronicles to discern administrative developments, therefore, could not make

much progress. The information is fragmentary and somewhat unreliable.

Another source was relied on to fill in the lacunae. This was the body of

precedents or traditions coming to the early Ottoman principality from the

Islamic heartlands through the mediation of the Seljuk state of Rum and its later

overlord, the Ilhanid Empire.13 The Ottoman's institutional debt to the

10See Giese, Apz., pp. I75-I77. The importance of the juxtaposition offeth etmek (to

conquer) and kaleme almak (to record) was pointed out to me by Professor Rudi Lindner

of Tufts University.

11Atsiz, Apz., pp. 1i8, I39. The view is shared by other works of the genre, such as

'Ahmedi' in Nihat Sami Banarli, XIV. aszr Anadolu fairlerindenAhmedi'nin Osmanlztarihi: Ddsztan-ztevdrih-i miilik-i dl-i Osman ve CemSidve Hursid mesnevisi (Istanbul, 1939),

p. 74. $ukrullah's Behcet in Atsiz, Osmanli Tarihleri, p. 57, and Banarh's 'Ahmedi,'

p. 83, relate how Bayezid I had to restrain the kadis from oppressing the people.

12 This general historical judgment of trial by ordeal is made much of in 'All, Apz.,

pp. I97-198. History in these chronicles is fundamentally moralistic, teleological, and

polemical.

13

Supplementing the early chroniclers with tradition (Turkish, Islamic, Middle

Eastern) is standard fare in twentieth-century Turkish historiography, represented in

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

506 Joel Shinder

Seljuk-dominated border principalities, to the Seljuks of Rum, to the Great

Seljuks of Iran-Mesopotamia and, later, to their successors, the Ilhanids, is

posited. This assumption bears examination under three headings: (i) composition and training of bureaucratic cadres; (2) Seljuk and Ilhanid precedents; and

(3) forms of the tradition of the vizierate.

There is some evidence that the Ottoman chancery scribes early in the fifteenth

century relied on earlier collections of letters and other forms of guidebooks from

non-Ottoman lands in their task of creating an Ottoman methodology for

recruiting, training, and entitling the membership of the scribal cadres. Their

sources were of three kinds: insa or miinseat (examples of correspondence, both

official and unofficial); 'mirrors for princes' (books of counsel by fathers for

sons, or by viziers for princes or sultans); and adab (collections of anecdotes,

homilies, and excerpts from classics in prose and poetry). The first genre related

directly to the functions of the early administration, the second to the general

rules which governors should follow both to maintain power and to rule justly.

The third was concerned with 'discipline,' the achievement of cultural refinement and wisdom which supporters of the state were to cultivate not only for

the prestige of the state itself but also for the very identity of the bureaucratic

elite in a corporate society.

The oldest known Ottoman insa is the Teressiilof the poet Ahmed-i Da'i, who

died after 1421. Based on Arabic and Persian texts, the Teressiil consists of two

parts, the standing form for such works. Part One contains advice to scribes,

and the rules prescribed here are termed edeb, Turkish for adab. Part Two is

the practical section, where models of letters and forms of address are presented

to exemplify the theoretical considerations of the introduction. The usage of

the term edeb is an interesting indication of the kind of appreciation early

Ottomans with their pragmatic bent had for classical Islamic genres. The

author's personal career is also interesting in the light of the market toll story of

'Asikpasazade, inasmuch as he first served under the Germiyan prince Ya'kub

before entering the service of the Ottoman Emir

Beg II (I387-1390, 1402-1429)

and

Sultan

Murad

II. Perhaps this is 'the man from Germiyan'

Siileyman (1405)

displaced one century!14

The Teressiil'simportance in the formation of an Ottoman chancery, however,

is not easily assessed. Bj6rkman15and Tekinl6 detect parallels and continuity,

three generations of scholarship: Zeki Velidi Togan, Umumi Tiirk Tarihine Girif,

Vol. I, En Eski Devirlerden I6. Asra Kadar (Istanbul, I946); I. H. UzuncarSlih, Osmanli

Devleti Teskildtzna Medhal (Istanbul, 1941); and in the works of Halil Inalclk as cited.

14 Ismail Hikmet

Ertaylan published a facsimile of the Terressiil in Ahmed-i Dd'Z,

Hayatz ve Eserleri (Istanbul, 1952), pp. 325-328. Also see W. Bjirkmann, 'Die Anfiinge

der tiirkischen Briefsammlungen,'

Orientalia Suecana, 5 (Uppsala, I956), 22-23, on insa

forms. A possible source for the Terressiil was published by Adnan Sadik Erzi, ed.,

Selfukiler Devrine did Insa Eserleri . . . (Ankara, I963).

'5 Bjorkman, 'Anfinge,' p. 29.

166inasi

Tekin, ed., Mendhicii'l-InSa: The Earliest Ottoman Chancery Manual by Yahyd

bin Mehmed el-Kdtib from the i5th Century, in Sources of Oriental Languages and Literatures: Turkic Sources, Vol. II (Roxbury, Mass., I971), p. II.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 507

respectively, in inSa from Sultan Mehmed I (I403-I421) through Sultan

Mehmed II. Tekin goes further, concluding from the 1412 Bursa copy of the

famous Persian Sa'adetndme (written around I307 by 'Alaeddin-i Tebrizi) of

the Ilhanid period that 'the Ottomans are copying the administration and

institutions of the Selcuks (sic) and Ilhanids.'17 Barkan is more cautious in this

respect but still subscribes to the view that models and parallels constitute

grounds for concluding the identity of institutions and practices without regard

to region and period or nature of absorption into the Ottoman realm.l8

However difficult the problems posed by the use of insa literature among the

early Ottomans, the influence of the 'mirrors' genre together with that of adab

is even harder to establish with firm evidence. Nizam al-Mulk's famous Siyasetname and the writings of Nasir al-Din Tisi were probably read. A translation

of Kai Ka'fis's Qabfs Ndma from Persian into Turkish was certainly made for

Murad II in his first reign (1421-1443), and Turkish manuscripts are more

numerous than those in the original Persian,19 but the degree to which these

tracts on Oriental governance actually shaped the Ottoman effort in the construction of an administration cannot be determined. The ideals expressed in

such works may well have been shared by early Ottoman scribes, however, even

if their own conditions were quite different. A look at this ideal is necessary,

therefore, provided that it is ranked in the category of theory or aspiration. It

would be misleading to view the ideal as a product or reflection of realities.

The ideal is founded in the golden age of Abbasid rule (ca. 750-900). Under

the Abbasids 'administrative appointments were likely to be made from

candidates belonging to a rather narrow circle of families. These families were

in possession of the secrets of government technique, they were familiar with

empire conditions, and they had the necessary connections.' Offices were not

hereditary, but professions like the military and the bureaucracy required

special knowledge and abilities, so they were largely exclusive. Where clerks

tended to be free men or mawali (non-Arab clients) and Persian, soldiers tended

to be freedmen and slaves of Turkish or other non-Arab and non-Persian

descent.20

If the Ottoman scribal corps of the early period aspired to an equal degree of

exclusivity, they may well have sought the cultural identity and etiquette which

accompanied the Abbasid civil service corps. That cultural form has been

ascribed as a Bildungsideal, polite education or, in Arabic, adab. The original

connotation of this term was 'the discipline of the mind and its training ...

17 Ibid.

18Omer Lutfi Barkan, XV ve XVI tncz Aszrlarda Osmanlz

Imparatorlugunda Zirai

Ekonominin Hukuk ve Mali Esaslarz, Vol. I, Kanunlar (Istanbul, 1943), pp. lxxi-lxxii.

On the problems involved in the use of insa model documents for historical purposes, see

Irene Beldiceanu-Streinherr, Recherchessur les actes des regnesdes sultans Osman, Orkhan

et Murad I (Monachii, Romania, i967), passimn.This is a critical analysis of several early

texts.

19 Levy, Mirror, p. xxi.

20 von Grunebaum, Medieval Islam, p. 213.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

508 Joel Shinder

characterized by combining the demand for information of a certain kind with

that for compliance with a code of behavior.' Although the religious judge and

theologian were trained strictly in the sciences of tradition, canon law, and

scholastic theology, the perfect kdtib or scribe had to be competent in grammar,

law, theology, literature, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, lexicology, political

theory, and the science of administration. The ability to recite the Koran and

Traditions by heart was also necessary. In fact such encyclopedic knowledge

was really narrowed to grammar, belles lettres, and history on the theoretical

plane, and calligraphy and style on the practical level. Both recruitment and

training, therefore, suggested preference for the all-rounder who could pass

freely through the bureaucracy and assume functions as diverse as chancery and

finance with equal facility.21

From the Abbasid ideal to Ottoman practice a yawning gap of almost five

hundred years exists. Many have tried to bridge the empirical gap through

studies on Seljuk and Ilhanid administrative organs and methods. First the

Great Seljuks in Iran and Mesopotamia, then the Seljuks of Rum in Asia Minor

proper and, finally, the Ilhanids with supremacy in both regions are held to

have mediated the Abbasid-Ottoman exchange with but a few Mongol-Turkic

variations. The full Abbasid apparatus, therefore, is seen to have been as readily

available to the Ottomans as the published traditions of the Prophet were to

Muslims of that age.

Under the first two Ottoman princes, Osman and Orhan (together, ca.

1281-1326), the structure of the Ottoman state and its administrative methods

were probably very similar to those of the other Anatolian principalities at best.

Little more than this statement of probability can be hazarded. Not even the

very officials of the early Ottoman state are clear. For example, an important

finance officer for the Seljuks of Rum was the mustawfi. His office and duties

may be a precedent for the Ottoman finance officer, the defterdar, or for the

commissioner of the cadaster, the defter emini. The inception of neither Ottoman

office, however, is known accurately. Likewise, just as the Seljuk royal council

(divan-i hdss) may be the model for and the functional equivalent of the Ottoman

council (divan-i hiimdyun), the exact functions and ranks of member officials

concerned with military, judicial, financial, and other affairs could and probably

did differ considerably.22Because the Seljuks and the Ottomans are quite alien

to the modern reader, it is easy to accept functional equivalency based on

titulature and vice versa. The faith, the culture, the language, and the civilization

seem to be the same in each case. This argument, however, would have the

Congress of the United States of America and the Parliament of the United

Kingdom functionally equivalent entities in respects going far beyond the

21

and Walther Hinz, 'Das Rechnungswesen orientalIbid., pp. 213, 250, 253-255,

ische Reichsfinanzimter im Mittelalter,' Der Islam, 29 (I950), I-2.

22 Although

many parallels may be sought, or analogues found, fundamental differences

obtain between various Seljuk offices (in functions, hierarchical position, and power) and

the later Ottoman forms. This is clear in the work of Osman Turan, Tiirkiye Selfuklularz

Hakkznda Resmi Vesikalar: Metin, Terciime ve Arastzrmalar (Ankara, I958), pp. I-62.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 509

responsibility of legislation and the relationship of these bodies to 'the people.'

And in this case, after all, there is a direct historical link between the two

nations. Historical differences do in fact obtain to alter institutions even in

the proximate case of the Seljuks of Rum and the Ottomans. The case for the

Ottoman timar's deriving from the Byzantine pronoia rather than from the

Seljuk iqtf' is cogent enough in itself to call for significant changes in administration.23 It is hardly proper, then, to fill in early Ottoman unknowns with Seljuk

vaguely knowns.

Although the case for the Seljuks is weak, that for the Ilhanids from the reign

of Shazan (I294-I304) and his vizier Rashid al-Din as the true precepts of

the Ottomans in the field of government is more coherent. Ilhanid and the later

Timurid administrative handbooks are found in the libraries of Istanbul. The

use of Persian phrases in official records and the adoption of the Persian solar

calendar for the fisc, as well as the Ottoman use of siyakat cipher script for

financial registers, could stem from Ilhanid or Ilhanid-Seljuk practice.24 Some

malefactor, after all, had to create that cipher which has blinded more than one

Ottomanist. The wording of Ilhanid berats, which certified various state

liabilities to individual parties, is similar to that of Ottoman documents of the

same name.25From evidence of this nature, the doyen of Ottoman history to the

imperial age, Halil Inalclk, asserts that Sultan Bayezid I introduced the full

'Turkish-Islamic' system of central government as developed in Persia under

the Mongol Ilhans.26

This system included provincial land and population surveys, fiscal methods,

a central treasury, and a bureaucracy. Dominant in the system was Bayezid's

extension of his personal ghulam-kapzkulu or slave corps. One religious judge

turned territorial prince actually called Bayezid 'son of a Mongol, totally lacking

knowledge and grace,'27so great did he sense Mongol influence at the Ottoman

court. The similarity of Ilhanid and Ottoman administration is clearest in the

forms of official registers maintained. Under the Ilhanids seven basic types of

registers have been described.28 These include the following: a journal for daily

transactions and appointments; a general state-of-the-treasury register; a

register of ordinary payments; a register of working capital; revenue-expenditure

books for individual cities and provinces; a general register of the realm's

total revenues; and books of regulations on taxation and other matters. Three

of the types (the first, third, and fourth) bear the same names used in the

Ottoman system, if for different purposes (ruizname,tevcihat, and tahvil7t). The

Ilhanid extraordinary tax known as 'avdrid and the tax levied in kind to provide

23 ClaudeCahen, Pre-OttomanTurkey(New York, 1968), pp. I82-183.

24 Hinz,

pp. 4-6, I3.

Rechnungswesen,

25 Ibid., pp. 20-22,

and I. P. Petruchevsky,'The Socio-EconomicConditionsof Iran

under the Il-Khans,' in The Cambridge

Historyof Iran, Vol. V, The Saljuqand Mongol

Periods (Cambridge,

26

I968),

p. 494.

Inalcik, 'Emergence,' p. 280.

27 Togan, UmumiTurk,p. 33I. Togan (pp. 329-330), is in agreementon the synthetic

'Turkish-Islamic'system of centralgovernment.

28

Hinz, Rechnungswesen, pp. 114-134.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Joel Shinder

51

food and fodder for the army in a given district, the 'ulffa tax, have exact

Ottoman counterparts in the same meaning.29 Finally, the Ottoman practice of

having secular kanun/yasak regulations side by side with shari'a prescriptions is

also an Ilhanid practice.30 Moreover, Ilhanid land tenure fell into four general

categories, each of which has its Ottoman analogue: state lands; private royal

domains; lands of the religious institutions and pious endowments; private

lands (mulk).This categorization, however, preceded the Ilhanids as much as it did

the Ottomans in accordance with custom and Holy Law. Besides, the tenacity

of landed classes is a well-known historical phenomenon, and this certainly

affected classification of lands.

The evidence admits a strong case for Ottoman-Ilhanid institutional ties.

Nonetheless, even in that body of material much is left to be desired. Whether

particular officials like the Ilhanid defterdar-i memalikand the Ottoman defterdar

of the early period held similar rank and fulfilled similar roles in government is

a matter for conjecture. Moreover, the general prejudice of Orientalists for

'Islamic' governments ignores the possible influence on the Ottomans of nonMuslim Mongol-Turkic states north and east of the Black Sea. The kinds of

registers the Ottoman kept, however like those of the Ilhanids, give few clues

apart from the similarity itself to the method and timing of borrowing. Timing

is particularly difficult to establish owing to the formalism of the diplomatics

involved. As in the Seljuk case, therefore, a general structure of 'Islamic' or

'traditional Near Eastern' government cannot be assumed to presuppose

functional equivalency, however great the force of tradition and precedent.

Circumstances, policies, interests, and alignments clearly differentiate the

Ottomans from their colleagues in government throughout the Muslim world.

These considerations suggest the tendency in earlier approaches to advance

the idea of continuity in Middle Eastern governing traditions to the detriment

of innovation or change. Some kind of search for a stereotypical or paradigmatic

'Muslim government' seems to be in progress, despite the prior conclusion that

the attempt in the Muslim world to create a Muslim government has consistently

failed! A look at the institution of the vizierate is an important step in shifting

the balance to the side of change. The example is particularly crucial in that, of

the many innovations introduced by the Ottomans, the grand vizierate is outstanding for its effects on the administrative history of the empire.

The Arabic wazir - literally, one who carries a burden - has the sense of aide

or counselor.31 The office is neither a direct borrowing from Sassanian practice

nor a static tradition. By the sixth century the Sassanian equivalent, the buzurg

framdddr, was in decline or non-existent, and the Umayyads had no first minister

Petruchevsky, 'Iran under Il-Khans,' pp. 532-533.

until Ghazan's

Togan, Umumi Tirk, p. 330. The Ilhanid state was non-Muslim

conversion, and this may account for the dual legal system. The Ottomans produced

regulations under different conditions; namely, the absorption of largely non-Muslim

areas with local codes of law into a state whose leadership was Muslim.

31 Dominique

Sourdel, Le Vizirat 'Abbdside de 749 d 936 (I32 a 324 de l'Hegire), Vol. I

(Damascus, 1959), pp. 50-54.

29

30

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 511

of the kind the Abbasids were to develop when they shifted the seat of government from formerly Byzantine Syria to formerly Persian Mesopotamia.32 The

first person to hold the title was Abfi Salama, officially saluted wazir dl Muhammad by the Kufan army in A.D. 749. As the salutation indicates, the office was

coincident with the Abbasids' new regime of increasing orthodoxy complemented by oriental influences, which was mediated by the non-Arab secretarial

classes.33

Abbasid viziers were most often recruited from the central or provincial

administration and were secretaries of recognized competence. While court

personnel rarely entered the office, administrators of the fisc were especially

prominent. In time, recruiting was carried out almost entirely among the awlad

al-kuttdb, sons of the scribal corps, thus generating great vizieral dynasties.34

Functionally, the Abbasid vizier headed up the scribal corps and was responsible

for their work in three major areas: applying the injunctions of the Holy Law

in fiscal matters; resolving extra-shari'a problems; and executing the will of the

caliph according to law. The vizier, therefore, stood between the Holy Law and

the caliph's discretionary powers in those areas outside the purview of the sacred

code. His dual role was most effective when a special relationship obtained

between himself and the caliph. In this relationship the vizier acted as 'tutor'

of the caliph at the same time that he was his servant and personal secretary.

The personal relationship between sovereign and servant, however, was all too

often jeopardized by palace intrigue and by the attempts of some servants themselves to become masters. Through the authority delegated to him, the vizier

could place his own men in crucial positions and influence policy in all spheres,

including the army. On the other hand, a vizier was vulnerable in that he did

not have complete control over his own staff. Military commanders frequently

interfered in the vizier's job. The extent of the minister's powers, therefore,

ultimately depended on his personal prestige and talents, as well as on his ability

to profit from his special relationship to his master. Vizieral instability in the

face of caliphal authority and rival groups marred the experience of the Abbasid

period even before the caliphal master lost his power to praetorians. The vizier

had no weapon to match the brute force of the army. Even his control over the

state finances proved inadequate. The vizier, it would seem, required a military

command of his own.35

These limitations notwithstanding, for a brief period during the late ninth

and early tenth centuries the vizierate reached its pinnacle of administrative and

political power, even nominating caliphs. From that time a number of theoretical

tracts justify the office and set down guidelines for its holders. Mawardi, for

example, distinguished two forms of vizierate, the vizierates of delegation and

of execution, and gave them a Koranic justification. He advised the vizier to

32

Ibid., pp. 41-43.

33

Ibid., pp. 59-6I, 65-66.

34Ibid., Vol. II (Damascus, 9I60), pp. 565-568.

35

Ibid., pp. 6I5-656, 664-667.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

512

Joel Shinder

protect the imdm-caliph and the umma, and he cautioned the sovereign to

maintain control over the vizier and prevent the creation of an equal and rival

power in the state. No legal framework to secure this worthy end of checks and

balances was outlined. Consequently, in practice the office depended on the

arbitrary will of the sovereign who created it.36

Under the Great Seljuk sultans, the political successors to the Abbasids, the

institution of the vizierate suffered the same weaknesses. The military acted

independently of the vizier, the cooperation of sultanate and caliphate was seldom

realized, and the attempt to link religion and state through the madrasa system

of higher education for public servants failed. The vizier's patronage function

resulted in factionalization, and the vizier's hold over the army through his

control of the treasury disappeared when direct support by land grants was

instituted. Finally, the sultans often went over the heads of their ministers by

consulting directly with subordinates in the bureaus.37

As an institution of government the Abbasid-Seljuk vizierate was not a

homogeneous unit ready for Ottoman adoption. From an advisory post it became

an office directing much but not all of civil administration. Its base was the

discretionary power of the sovereign, sultan, or caliph. In its most centralized

form of the Seljuk period it still had no substantial control over the military

forces of the state, so that even the personal prestige of a particularly able vizier

only served to excite the envy and fear of the military commanders. The Ottomans certainly accepted the title of vizier for their head of government and other

officers of state. They did not assume the burden of that office's full and turbulent history. Neither continuity nor evolution characterizes that history. Neither

continuity nor evolution may be presumed for the Ottoman vizierate. The

themes and precedents which have informed the study of Ottoman administrative history are proved misleading or fallacious. Some of the circumstances

which shaped the early Ottoman experience in administration support this

assertion.

The structure of the Ottoman state under the first two princes, it has been

stated, was similar to that of the other Anatolian principalities, successors to the

Seljuks of Rum and dependents of the Ilhanid empire. Territory in the principalities was divided among the sons of the prince and other family members.

Each member acted at will in his own lands. The leadership was elective, and

the headman was merely primus inter pares. It is thoroughly appropriate, then,

that the Ottomans are known as such, Osmanhs, followers of Osman and his

line. Osman's reign, however, was not very remarkable. His property at death

reportedly consisted of a province, but no gold or silver; a robe, some armor, a

salt cellar, a spoon-holder, some houseboots, several horses, some sheep, a few

oxen, and nothing more.38 The spectacular expansion of the family's holdings

36

Ibid., pp. 715-7I7.

37Carla L. Klausner, The Seljuk Vezirate: A Study of Civil Administration, io55-II94

(Cambridge, Mass., 1973), pp. 26, 40, 44-45,

38

'Ali, Apz., pp. 36-37.

88.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 513

commenced in the reign of Orhan. Ibn Battuta describes him as the greatest of

the Turkmen kings and the richest.39 Both he and Gregory, Archbishop of

Thessalonica (I347-I360), however, agree that Orhan preferred the outdoors to

the foul air and crowds of the cities and towns he held. He never gave up his

tents for the sake of a palace, a sure sign of vigor in the mind of Ibn Khaldun,

another commentator.40

At some obscure point the Ottomans stopped being simple heads of seminomadic tribes with winter and summer pasturages and became governors of an

organized frontier march. Historians for the house developed a legitimacy

argument that involves Seljuk nomination of Osman as an independent governor.

Effective nomination, of course, would have come from the Ilhanids, but the

degree of central control over the Anatolian periphery can in fact be minimized.

Vassal or independent ruler, Osman's actions bespeak the absence of central

constraints. His military feats were not limited to the ghazi struggle against

Byzantium but included as prey long-held Muslim lands. The Muslim Ottomans

occupied the land of other Muslim princes, who menaced each other as much

as Byzantium, if not more so.41 It would be a mistake, however, to conceive of

the Ottomans at this early date as a highly centralized state itself. The conquest

of Thrace, for example, was not accomplished by a well-oiled, centrally directed

and thoroughly coordinated military machine matched by an effective administrative apparatus. Non-Ottoman and Ottoman leaders acted on their own to set

up political entities in Thrace. These had a Greek-speaking peasant base, kadis,

regional commanders (subasz)and army judges. Yakub, Haci ilbeyi, and Siileyman (an Ottoman scion) were among the more prominent of these Thracian

entrepreneurs. After Siileyman's death no Ottoman was sent to replace him, but

the conquest of Thrace continued.42

On emerging from the black hole in their history, ca. 1364-1381,43 the

Ottomans are seen to have begun their steep ascent into the ranks of the mighty.

Hidden in this lacuna, however, is the formation of the janissary corps, the

Thracian take-over, and the development of an administration. When the

murkiness clears Murad I (I360-1389), Orhan's successor, appears as grand

emir or prince, possibly signifying his success in gaining control over the

independent agents in Thrace who felt threatened by Byzantine and south Slav

pressures. The janissary corps may well have been initiated with this end in

view.44 The final step in the Ottoman assertion of unitary rule in their house

was taken by Bayezid I when he assumed the attribute hiimayun, imperial, which

39 H. A. R. Gibb, trans., The Travels

of Ibn Battuta A.D. 1325-1354,

Hakluyt Society,

Series II, Vol. CXVII, Vol. II (Cambridge, I962), p. 452.

40 G. G.

Arnakis, 'Gregory Palamas among the Turks and Documents of His Captivity

as Historical Sources,' Speculum, 26 (1951), II3.

41

Beldiceanu-Steinherr,

Recherches, pp. 70-7I.

42

Ibid., pp. 45-47.

43 The lack of material for this period was first noted by Franz Babinger, Beitrdge zur

friihgeschichte der Tiirkenherrschaft in Rumelien (14-15 Jahrhundert) (Munich, I944),

p. 76.

44Beldiceanu-Steinherr, Recherches,pp. 47-48, 241 and n. 2.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

514 Joel Shinder

his successors Musa and Mehmed I continued to use.45 While an elevated

attribute, a loyal military force and preeminency among the princes of the region

are all manifest by the end of the fourteenth century, the growth of a central

administration is masked. Where and who are the Ottoman missi dominici?

According to the ghazi thesis of Paul Wittek, Ottoman success was dependent

on the continguity with Byzantium and the appeal to two diametrically opposed

groups, the ghazi warriors of the faith and the representatives of high Islamic

urban civilization, the ulema. The hinterland was considered the source for the

latter, the only social group deemed capable of stabilizing the ghazi state. The

ulema, with their knowledge of Islamic principles and methods of administration, were thought to have brought to the Ottoman capital at Bursa a pacific and

tolerant Islam which guaranteed subject peoples communal independence and

a structured system of taxation, protecting them from the depradations of bootystarved ghazis. Artisans and merchants of the akhi fraternal organization followed

these chieftains of law and order and assured the Ottomans a high level of

productivity. The fraternal order was the first victim of the new society. Members with secular interests entered guild organizations (their origins unexplained),

and those with otherwordly concerns followed the dervish orders of mystics.

The ghazis were the next to suffer the jealousies of Osman's heirs, who identified

themselves with the ulema.46

On reconsideration, the Ottoman effort throughout was not so much to

harmonize tendencies as to ensure that favorable ones prevailed. The creation

of the janissary corps was a hedge against overdependency on the independent

forces of the other princes and tribesmen. An independent and quasi-religious

political, social, and economic organization such as the akhis could not be

tolerated. But Ottoman relations with their ulema were not completely thorough,

either. Early Ottoman support in the way of pious endowments was much

greater for the popular religious fringes than for the hinterlanders.47 The first

chronicles exaggerate corruption among the ulema in administrative posts,

especially during the reign of Bayezid I, and intimate that a blind eye was turned

on their abuses of authority. Bayezid, however, regulated the fines and fees that

officials were allowed to levy in their legal proceedings.48 The practices of

accumulating wealth, accounting for it, and creating a treasury to hold it cannot

entirely be laid at the doorstep of the ulema alone. The initiative in structuring

the ulema into an administrative cadre came rather from the Ottoman court

itself. The Ottomans, therefore, pursued an articulated policy which employed

45 Paul

Wittek, 'Zu einigen friihosmanischen Urkunden, II,' Wiener Zeitschriftfiir die

Kunde des Morgenlandes, 54 (1958), 244.

46 Paul Wittek, 'De la defaite d'Ankara a la prise de Constantinople,'

Revue des Etudes

See also G. G. Arnakis, 'Futuwwa Traditions in the

Islamiques, 12 (1938), 5, 12-I3.

Ottoman Empire: Akhis, Bektashi Dervishes, and Craftsmen,' Journal of Near Eastern

Studies,

12 (I953),

237,

240.

See the lists of monuments in Ekrem Hakki Ayverdi, Osmanlz Mimarisinin Ilk Devri,

Vol. I (Istanbul, I966), passim.

48

Giese, Apz., pp. 30, 42.

'Ali, Apz., pp. I97-I98;

47

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 515

all human resources at hand without any kind of ideological orientation reflected

in such terms as ghazi, hinterlander, ethical fraternity, or mystical order. In

their centralist policy the heads of the house found ulema supporters, among

others. Candarli Kara Halil Hayruddin Pasa is the outstanding example of an

'alim-turned-administrator and commander.49 The ulema was one important

source of recruitment for administrators, but it was not the only one. A vizier

named Bayezid Pasa was originally a sipahi, a cavalryman.50There was also a

standing Byzantine scribal class which has to be considered along with the nonByzantine Balkan scribal classes, most notably the Hellenized south Slavic

cadres of the Serbian period. A contemporary observer of the early Ottomans

described the Ottoman clerks as 'iaziti' (Turkish, yazici). These wrote in several

scripts (and languages?) and included Christian secretaries both at court and in

the provinces. Their employment in the provinces was primarily directed to the

preparation of cadastral surveys for the fisc.51 Since the Ottomans frequently

preserved features if not the bulk of pre-Ottoman Muslim and non-Muslim law

codes and customs, such scribal groups were important additions to the state

apparatus. They had an immediate, direct influence which was not always that

of 'the traditional Near Eastern State' on the development of Ottoman administration. After a conquest the scribes employed to write up the cadasters were

often men with local knowledge, themselves natives of the places recorded and,

therefore, recent additions to the broad ruling class. One such scribe was a slave

of an Ottoman general. Another scribe rose to a field command post himself.52

Just as the ulema did not monopolize scribal positions and traditions, neither

can they clearly be set apart as hinterlanders. In Rumeli (the European province),

especially, the ghazis under their various independent leaders elected their own

kadis to handle such administrative questions as inheritance and taxation. Thus,

frontier Turks, not all of whom entered Europe by way of Muslim Iran and

Asia Minor, infiltrated the ranks of the incipient 'Ottoman' ulema.53

Administration in the formative period of the state was primarily concerned

with the sultan's financial claims. The basic unit of rural exploitation was the

timar, the usufruct of which supported both civil and military servants of the

Osmanli household - the state, so to speak.54Ottoman scribes were responsible

for developing a systematic means of registration and assignment not only for

lands falling under the timar regime but also for the lands, forests, fisheries,

49 The importance of this family in the formative period of the Ottoman state is outlined in Franz Taeschner and Paul Wittek, 'Die Vezirfamilie der Candarlyzade (I4.-I5.

Jah.) und ihre Denkmiler,' Der Islam, 28 (1929), 60-115.

50Ibid., p. 95.

51 Speros Vryonis, Jr., 'The Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman Forms,' Dumbarton Oaks

275-276.

Papers, nos. 23 and 24 (I969-I970),

52 Halil Inalclk, Hicri 835 Tarihli Suiret-i Defter-i Sancak-i Arvanid (Ankara, 1954), pp

xvii-xviii.

53 Giese, Apz., p. 50; Franz Babinger, ed., Die Friihosmanischen Jahrbiicher des Urudsch.

Nach den Handschriften zu Oxford und Cambridge ... (Hanover, 1925), pp. I2-I3.

54 Irene Beldiceanu-Steinherr,

'Un Transfuge qaramanide aupres de la Porte ottomane:

reflexions sur quelques institutions,' Journal of the Economic and Social History of the

Orient, 26 (I973), I63-I64.

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

516 Joel Shinder

mines, markets, and customs posts excluded. This they did using every reasonable source or method at hand in the newly acquired regions. The system was

not so thorough in its uniformity as in its centralization, for the proprietary

rights of the emergent state and the usufructuary rights of individuals had to be

protected. The regulations that protected the rights of proprietor and tenants

and established the obligations of all persons holding any title to sources of

revenue came to be known as the sultan's kanun, his executive law, a law of

expediency and custom. Collections of kanuns for particular regions prefaced

the appropriate cadastral registers. More general regulations were collected into

kanunnames,a form of codification for the use of the public, especially the kadis

responsible for applying both kanun and sharz'a in their courts. From the

language of Mehmed II's kanunnameit can be inferred that the exemplars derive

from Bayezid I or Mehmed I. In the reign of Murad I individual questions of

proprietorship-tenancy probably were not recorded in writing.55 There are

references, however, to regulations for this period. A tentative conclusion is that

Murad I was the first sultan to make pronouncements which stipulated the

varieties of land tenure and the obligations these entailed.56 If this is indeed the

case, then the inception of true Ottoman central administration rests in Murad's

reign.

Important clues to the first cadasters produced by the administration come

from the earliest surviving cadastral register bearing the date 835/I431. It

displays a primitive chronology in the introductory section, which refers to an

asil defter, the original or source register, from the period of Mehmed I. The

inference from the phraseology is that the first register was completed under

Mehmed's father, Bayezid I, in whose reign come the first complaints in the

chronicles of bureaucratization.57 Umur Beg, the official responsible for the

composition of the register, was the son of a foot soldier who served under

Murad I and Bayezid I. Yusuf, Umur Beg's scribe, prepared the register in

tevki' script and not in siyakat, as is customary in later registers.58In every other

respect, however, the format is essentially that of the imperial age. The register

and chancery documents of the period are indicative of continued development.

The principles of Ottoman accounting and the instruments for the certification

of rights to individuals are not as yet fixed. There is no heavy-handed tradition

of administration and statecraft displayed here, nor is there a homogeneous

body of hinterland civil servants perpetuating such a tradition. That tradition,

will be manufacturedin the sixteenth century by chroniclers of the ulema class

rather, seeking for themselves and their colleagues greater influence in

government.

One is nonetheless left with a final question. Was there some cohesiveness to

the emergent administrative class? If a rudimentary but normal mode of proBeldiceanu-Steinherr, Recherges, p. 245.

Babinger, Beitrdge, p. 58.

57

Inalcik, Hicri, p. xv. Refer back to the earlier comments on the chroniclers' views of

Bayezid I's policies.

58

Ibid., pp. xii-xiii, xvii.

55

56

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Early Ottoman Administration in the Wilderness 517

gression can be suggested for the highest administrative positions as described

in the chronicles, it would look something like: mosque professor; kadi of

Bursa; kadiasker, the judge-advocate of the army; nisancz, the head of the

chancery and keeper of the seal; vizier; and, finally, grand vizier. For the early

period as seen in the chronicles the ulema career seemed to lead directly to the

highest office in the realm below that of sultan. Cohesiveness would seem to rest

in the prestige of the ulema class. So little is known of the early viziers, however,

that such a construction is really quite unwarranted. What made a vizier a grand

vizier, when and who the first grand vizier was, are questions that cannot be

answered. The likelihood is great that there was no clear differentiation of roles

either by training or by function during the formative period. High-ranking

commanders loyal to the house of Osman, ulema figures who shared abilities in

politics, war, and law and, finally, local but non-Ottoman elites contributed to

the executive classes in Ottoman government. The administrative cadres beneath

the highest figures were also mixed, including Turks and non-Turks, scribes of

pre-Ottoman states (Muslim and non-Muslim), and prominent local figures who

were not always even literate! Administration may not have meant fulltime

employment for most of the personnel involved. The rate of expansion probably

exceeded the abilities of government to govern, which helps explain the sinewave course of Ottoman expansion in Europe and Asia. Moreover, local initiative

takes first prize in Ottoman history, even in the periods of greatest centralization.

One would expect the absence of a cohesive administrative corps in the early

period.

It is erroneous, therefore, to think that the government of the Ottoman

principality was the microcosm of the empire's government or a seed of the

'traditional Near Eastern State' planted in the fertile soil of Asia Minor by

horticulturists of the ulema class; or that government itself simply resulted from

the conflict of ghazi and ulema, Osmanli slaves and free Turkish nobility. The

question was not which elements would succeed or how far 'Ottoman State'

would withdraw from 'Ottoman Society.' It was which ruler and of what house

would prevail. Ottoman survival following the Battle of Ankara (I402) was

certainly furthered by the administrative abilities and capabilities of the dynasty's

servants, but these functionaries were far more flexible and imaginative than

the themes and traditions which have been advanced to classify their achievements. If the Ottoman example is any indication, the comparative study of

Islamic government is on a most inauspicious course. Might one yet cleanse

these Augean stables without detriment to generalization and the usefulness of

comparison?

MINNEAPOLIS,

MINNESOTA

This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Sat, 01 Aug 2015 09:20:15 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)