Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Correspondence: Abortion Rates Still Rising

Enviado por

Ayu Ersya WindiraTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Correspondence: Abortion Rates Still Rising

Enviado por

Ayu Ersya WindiraDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CORRESPONDENCE

* All letters must be typed with double spacing and signed by all authors.

* No letter should be more than 400 words.

* For letters on scientific subjects we normally reserve our correspondence columns

for those relating to issues discussed recently (within six weeks) in the BMJ.

* We do not routinely acknowledge letters. Please send a stamped addressed

envelope ifyou would like an acknowledgment.

* Because we receive many more letters than we can publish we may shorten those

we do print, particularly when we receive several on the same subject.

Abortion rates still rising

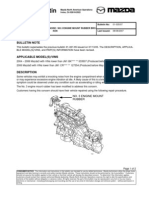

SIR, - A recent report from the Office of Population

Censuses and Surveys' has been widely quoted in

the press,2 3and was reported by Ms Luisa Dillner,4

as indicating that the abortion rate has tripled in

the past 20 years in England and Wales. Detailed

analysis of these figures, however, shows that

requests for abortion have remained remarkably

constant since 1972 (figure).

The initial rapid rise from 3-5/1000 women aged

15-44 in 1968 (the first year when abortions were

notified) to a level rate of 11 0/1000 in the 1970s

probably reflects the increasing availability of legal

termination of pregnancy and corresponds to a

decrease in illegal abortion. Much of the modest

increase since then (35%) can be explained by

demographic changes rather than a profound

change in women's requests for abortion. Women

born during the "baby boom" of 1960-5 reached

sexual maturity during the 1980s, and hence a

larger proportion of the female population is at risk

of unwanted pregnancy. The Office of Population

Censuses and Surveys calculated that because

there has been an increase in the proportion of

women aged between 16 and 29 (a group that has a

higher termination rate than older women) without

any change in the age specific termination rates the

number of terminations would have been expected

to increase by 14% between 1972 and 1989.

The remaining increase is likely to be due mainly

to a gradual change in the attitudes of doctors,

and particularly gynaecologists, to therapeutic

abortion in certain parts of the country. In Scotland

there were appreciable regional differences in the

abortion rate in 1972, with the rate in the west

being half that in the north and east. Though the

rates in the east and north have remained fairly

constant over the past 20 years (for example, that

in Grampian), the rate in Greater Glasgow has

doubled to reach the national average. These

differences probably reflect the influence of two

X1

16

pEngland and

/ Wales(o)

14

12

A ,

c~~~~

E

10

8

8

d;/;96 so -'>

<

>rGlasgow (e)

Grampiana(*)

Scotand (o)

S6 *i

Z 2

1970 1974 1976

1980 1984

1988

Abortion rate among women aged 1544 in Grampian

region, Greater Glasgow, Scotland, and England and

Wales, 1970-88

*Figures for North East Scotland Regional Hospital Board. tFigures

for West ofScotland Regional Hospital Board.

BMJ

VOLUME 303

7 SEPTEMBER 1991

eminent senior gynaecologists. My father, Sir

Dugald Baird, who worked in Aberdeen, played an

important part in supporting the change in the

Abortion Law in 1967; Professor Ian Donald in

Glasgow was vehemently opposed to therapeutic

abortion. Though religious and social factors may

have had some role, it seems unlikely that the rise

in abortion rate in Glasgow is totally unrelated to

the retiral of Professor Donald in 1976. Similar

regional differences in attitudes existed throughout

England and Wales, and hence the increase in the

abortion rate nationally probably reflects the

gradual levelling out of provision of abortion

services rather than an increased resort to abortion

as a means of controlling fertility.

A major factor determining the demand for

abortion is the provision of contraceptive services.

The abortion rate in Scotland (9-8/1000 women

in 1989) is lower than that in most European

countries and less than one third that in the United

States' partly because contraception is widely

available to all sections of the community from the

NHS. Recent attempts by many health authorities

to limit the provision of "social" sterilisations and

to reduce budgets for family planning services may

lead to a rise in the incidence of unplanned and

unwanted pregnancies. The consequent increase

in the demand for therapeutic abortion would be

very undesirable at a personal level and would put

increasing strain on medical services.

DAVID T BAIRD

Centre for Reproductive Biology,

Department ot Obstetrics and Gynaccology,

University of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh EH3 9EW

I Office of lopulation Censuses and Surveys. 'I'rends in abortion.

In: Population trends 64. London: Government Statistical

Service, 1991:19-29.

2 Fletcher D. Abortion rate has trebled in 20 years. Daily Telegraph

1991 June 19:4(col 1).

3 Hunit L. Abortions on the increase. Independent 1991 June

19:4(col ).

4 Dillner L. Abortion rates still rising. BMJ 1991;302:1559-60.

(29 June.)

5 Henshaw SK. Induced abortion: a world review. Family

Planning Perspecti'ves 1990;22:76-89.

Vital statistics of births

SIR,-The measurement of maternal mortality

is important enough that a minor point in Dr

Geoffrey Chamberlain's excellent paper' deserves

mention. The denominator for maternal mortality

in a given year is either the total number of births

or the number of live births during that year, not

the number of maternities-the term maternities is

ambiguous. The World Health Organisation's

definition states that "A 'maternal death' is defined

as the death of a woman while pregnant or within

42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective

of the duration and the site of the pregnancy,

from any cause related to or aggravated by the

pregnancy or its management, but not from

accidental or incidental causes" and goes on to

say that "the denominator used for calculating

maternal mortality should be specified as either

the number of live births or the total number of

births (live births plus fetal deaths). Where both

denominators are available, a calculation should be

published for each."2

To allow for an extension of the period during

which deaths can be related to pregnancy or its

outcome, the 1989 international conference for the

tenth revision of the International Classification of

Diseases introduced the concept of late maternal

death: "A 'late maternal death' is defined as the

death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetric

causes more than 42 days but less than one year

after the termination of pregnancy."2

Similarly, the conference has introduced the

concept of "pregnancy related death" to permit

classification of deaths of women while pregnant

or when recently delivered, even though local

facilities may not allow the cause of death to be

identified as "related to or aggravated by the

pregnancy or its management." A pregnancy

related death is thus defined as "the death of a

woman while pregnant or within 42 days of

termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the cause

of death." It. is likely, for instance, that some

homicides and suicides of pregnant or recently

pregnant women fall into this category, and

accidents may also be considered in this light,

in so far as fatigue or reduced mobility in advanced

pregnancy affects ability to avoid or survive

accidents.'

A C P' L'HOURS

M C THURIAUX

Division ot Epidemiological Surveillance and

Health Situation and Trend Assessment

Strengthening of Epidemiological and

Statistical Services,

World Health Organisation,

1211 Geneva,

Switzcrland

I Chamberlain G. Vital statistics of births. BMJ 1991;303:178-8 1.

(20 July.)

2 International conference for the tenth revision of the International

Classification of I)iseases, Geneva, 26 September-2 October

1989. Wttrld Health Statistics Quarterly 1990;43:204-45.

3 Fortney JA. Implications of the ICD-I( definitions related to

death in pregnancy, childbirth or the puerpwrium. World

Health Statistics Quarterly 1990;43:246-8.

Nursing: an intellectual activity

SIR,-For doctors to comment on matters concerning nursing risks touching a raw nerve-the

"doctor's handmaiden" nerve-but the forthright

views of June Clark, a professor of nursing,

deserve discussion.' Doctors and nurses need each

579

other. They learn from each other. And if they

don't work well together it's the patient who

suffers. Both professions ought to be mature

enough to discuss the problems of the other from

time to time without coming to blows over it.

Our goals are surely the same. Those listed by

Professor Clark are the goals of all health workers,

not just of nurses. Certainly you can't be a good

doctor if you don't consider the whole patient, as

leaders of the medical profession like Lister and

Osler emphasised 100 years ago.

Secondly, I fear that many doctors will not be

happy with either of the suggested "two ways of

looking at nursing." Those who are said to look at

nursing in the first way (which is described as

the more prevalent of the two perspectives) are

accused of believing that nurses do not require an

understanding of why a task is necessary, how it

works, or what its effects will be. But surely

nobody thinks this. Anyone with a grain of sense

wants each member of a team to have as much

understanding as possible of what is being done for

a patient. Why else should nurses have lectures

from specialists explaining the thinking behind

different surgical and medical treatments?

As regards Professor Clark's second way of

looking at nursing, everyone will agree with much

of what she says and with the progress towards an

even better trained, understanding, and skilful

nursing profession. But it seems to me that to

achieve what she would apparently like to see for

all nurses (examining and history taking, thought

processes identical with those used in medicine,

sophisticated cognitive and social skills, and so on)

would mean that every nurse would have to go

through a course of training very similar to that at

medical schools.

We have all known nurses who, had they chosen

to do so, could have sailed through medical school

with flying colours. But there are many othersequally excellent and with equally good skill and

judgment in many circumstances-who would be

the first to agree that they could never compete or

cope at this intellectual level and wouldn't want to.

It doesn't help patients or anyone else to pretend

otherwise. To be blunt, what is at stake here, it

seems to me, is the credibility of those leaders of

the nursing profession who brush reality under the

carpet and talk as if all nurses were broadly the

same in this respect.

THURSTAN B BREWIN

Bray,

Berkshire SL6 2BQ

1 Clark J. Nursing: an intellectual activity. BMJ 1991;303:376-7.

(17 August.)

SIR,-IS Professor June Clark suggesting that,

though the thought processes in nursing are

identical with those in medicine, nursing alone

focuses on the "human response" and the "uniqueness of the individual"?'

Perhaps she has a vision of care provided by

a multidisciplinary team led by nurses, with

psychologists providing counselling or behavioural

management for problems that the nurse does

not have time for and doctors available to sign

prescriptions and undertake manual tasks such as

pinning femurs and performing tracheostomies.

When I become helpless, whether from illness,

advancing years, or sheer rage, I hope that there will

be someone in this multidisciplinary team to soothe

my fevered brow and, more importantly, to keep me

clean and dry, thus avoiding the bedsores that seem

so common.

S BRANDON

University of Leicester School of Medicine,

Leicester Royal Infirmary,

PO Box 65,

Leicester LE2 7LX

1 Clark J. Nursing: an intellectual activity. BMJ 1991;303:376-7.

(17 August.)

580

SIR,-Professor June Clarke's editorial on nursing

interested me as I am a qualified nurse as well as a

qualified doctor. When I decided on a career in

nursing I had only two 0 levels. Fortunately, I

passed the entrance exam and spent eight happy

years as a nurse. My training was intense and

stimulating and had a strong element of discipline.

I changed my profession not because I didn't enjoy

nursing but because I was searching for a different

sort of challenge.

I am saddened by the standards of nursing care

today. Nurses no longer have time to sit and

provide that all important emotional support.

They say that they are understaffed, but perhaps

they are too busy writing care plans and evaluating

the care that they have been too busy to provide.

I agree that nursing requires a good intellect, but

raising the entry requirement means that some real

nurses are excluded. After all, had I applied 10

years later to become a nurse I would not have been

accepted with my two meagre 0 levels. I believe

that standards are falling partly because of this

leaning towards academia. It is difficult to see how

a degree in nursing produces better nurses when

they spend more time in a classroom than at

the bedside. Of course good clinical research is

needed, but not at the expense of good nurses

on the wards, where practical skills are vital.

If nurses want to be "clinical specialists" why

don't they change professions like I did? Believe

me, the grass is not greener on the other side.

SALLY-ANN HAYWARD

London NW6 3HP

I Clark J. Nursing: an intellectual activity. BMJ 1991;303:376-7.

(17 Augist.)

SIR,-As I read Professor June Clark's editorial on

recognising nursing's intellectual component' I

thought of the women who, on several occasions,

have promoted my "physical and mental comfort,

healing, and recovery" and wondered what they

would have made of it. They would probably have

asked, "What on earth is she on about?"

Years ago I watched a district nurse restore my

badly burnt 80 year old grandfather through

convalescence to renewed self confidence. A

"considerable intellectual and emotional challenge"? She would have been mystified. She was

simply doing her job and doing it superbly; and she

was not exceptional.

The intellectual component has always been

present, and recognised. But we didn't call it that.

We called it basic intelligence and common sense.

To talk now of "coherent and holistic care" and

"extant definitions of quality care" is to use the

worst kind of academic jargon. Sadly, this is not an

isolated example-the whole article reeks of it.

I feel a sense of outrage on behalf of the women

who nursed me, some of whom became valued

friends of the family. If I was a young woman

considering nursing today I would be frightened off

by this article. I am afraid that many will be.

KATHLEEN NORCROSS

Birmingham B29 7JA

1 Clark J. Nursing: an intellectual activity. BMJ 1991;303:376-7.

(17 August.)

HIV transmission during

surgery

SIR,-We should like to clarify certain issues

raised by Dr A G Bird and colleagues.' These

remarks concern the case of the HIV infected

gynaecologist who agreed that the 1000 patients he

had operated on should be contacted.

Letters were sent to patients in the three districts.

They were offered initial counselling by telephone

helpline and then encouraged to attend for further

counselling and discussion at convenient centres.

Alternative arrangements for counselling were also

catered for, including home visits for those unable

to take time off work or with transport difficulties,

and an option of attending their own general

practitioner instead of the organised counselling

sessions. The general practitioners had been

advised separately about the nature of the incident.

No patients were discouraged from having a

test, and the genitourinary clinics were used only

for counselling and testing within one district,

where other facilities were not readily available.

That many patients chose to have a test after

counselling was in part related to their level of

anxiety on receipt of the letter. The role of the

counsellors was to offer impartial information and

not to persuade or dissuade patients from having a

test.

The Association of British Insurers, by recommending a waiver note for patients taking the test,

may have only confused its prevailing message. In

April 1991 a "statement of practice" was produced

by the association, reiterating that a negative HIV

test in the absence of lifestyle risk factors would not

jeopardise insurance premiums on any occasion. A

waiver notice was therefore not strictly necessary,

but the machinery to produce this had in any case

been put into operation well before the events

became public.

Whereas it may be claimed that the exercise

illustrated could have been used to provide even

greater epidemiological information, there is no

evidence from the evaluation of work carried out

locally in the health authorities of any "collective

denial" hindering epidemiological assessment.

Indeed, our objectives included acknowledgment

of the potential risk (however small), sympathetic

and confidential management of the individuals

concerned, and delivery of unbiased and correct

information to the public.

The success of the exercise cannot be judged by

the level of HIV testing achieved, but rather by the

dissipation of anxiety and uncertainty of all those

involved.

S C CRAWSHAW

R J WEST

West Suffolk Health Authority,

Bury St Edmunds,

Suffolk IP33 I YJ

1 Bird AG, Gore SM, Leigh-Brown AJ, Carter DC. Escape from

collective denial: HIV transniission during surgery. BMJ

1991;303:351-2. (10 August.)

Guidelines for doctors with HIV

infection

SIR, -In DrMichaelMorris'seditorialonAmerican

legislation on AIDS' the tired old guidelines from

the General Medical Council are repeated yet

again: "It is unethical for physicians who know or

believe themselves to be infected with HIV to

put patients at risk by failing to seek appropriate

counselling or act upon it when given."

This will not do. AIDS may eventually kill the

unfortunate surgeon who is HIV positive, but if

he abandons his livelihood poverty, loneliness,

depression, and debt will kill him sooner. His

family surely have enough to cope with without

losing their house and facing a mountain of debt.

If those eminent people who formulate such

guidelines truly believe them then we must pay

those whose counselling leads them to give up their

profession the full rate for the job they are leaving.

When the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and

Food destroys livestock to control an outbreak of

foot and mouth disease it pays the full market rate

for the animals it destroys, otherwise the farmers

would not always cooperate. If we really want to

BMJ VOLUME 303

7 SEPTEMBER 1991

Você também pode gostar

- Vital Statisitic of BirthDocumento1 páginaVital Statisitic of BirthAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- OG Informing Abortion Debate DR Christine BaileyDocumento2 páginasOG Informing Abortion Debate DR Christine BaileyYwagar YwagarAinda não há avaliações

- Making Sense of Health Statistics: Gerd GigerenzerDocumento2 páginasMaking Sense of Health Statistics: Gerd GigerenzerEndik SiswantoAinda não há avaliações

- Bjo 12363Documento10 páginasBjo 12363Khalida Nacharyta FailasufiAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy-Associated Mortality After Birth, Spontaneous Abortion, or Induced Abortion in Finland, 1987-2000 (2004)Documento6 páginasPregnancy-Associated Mortality After Birth, Spontaneous Abortion, or Induced Abortion in Finland, 1987-2000 (2004)The National DeskAinda não há avaliações

- Stillbirths: The Invisible Public Health Problem: Embargo: Hold For Release Until 6:30 P.M. EST, April 13Documento8 páginasStillbirths: The Invisible Public Health Problem: Embargo: Hold For Release Until 6:30 P.M. EST, April 13Akhmad Fadhiel NoorAinda não há avaliações

- Srep02362 PDFDocumento9 páginasSrep02362 PDFTriponiaAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy Related Mortality in The United States,.11Documento8 páginasPregnancy Related Mortality in The United States,.11melisaberlianAinda não há avaliações

- HI08 Comparing Payor PerformaceDocumento10 páginasHI08 Comparing Payor PerformaceCenterbackAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal MortalityDocumento12 páginasMaternal MortalityAli Mulla100% (2)

- 2011 - Unsafe Abortion and Postabortion Care - An OverviewDocumento9 páginas2011 - Unsafe Abortion and Postabortion Care - An OverviewJeremiah WestAinda não há avaliações

- Puerperal Sepsis WMSD Chapter7 RefDocumento9 páginasPuerperal Sepsis WMSD Chapter7 RefMuhammad JulpianAinda não há avaliações

- Obstetrics V13 Obstetric Emergencies Chapter Epidemiology of Extreme Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality 1710573094Documento11 páginasObstetrics V13 Obstetric Emergencies Chapter Epidemiology of Extreme Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality 1710573094antidius johnAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Landmark Nursing Research Studies: Changing Practice, Changing LivesDocumento24 páginas10 Landmark Nursing Research Studies: Changing Practice, Changing LivesNiala AlmarioAinda não há avaliações

- SR Statistics CCDocumento4 páginasSR Statistics CCNurusshiami KhairatiAinda não há avaliações

- Scottish Conservative Healthy Lifestyle StrategyDocumento20 páginasScottish Conservative Healthy Lifestyle StrategyAlexandruMincuAinda não há avaliações

- Studiu de CazDocumento27 páginasStudiu de CazAdina TomsaAinda não há avaliações

- RCOG InfertilityDocumento8 páginasRCOG InfertilityFatmasari Perdana MenurAinda não há avaliações

- Fetal Death UpToDate 2feb04 196028 284 18220Documento23 páginasFetal Death UpToDate 2feb04 196028 284 18220restuwidianaAinda não há avaliações

- Golding, 2007Documento25 páginasGolding, 2007DijuAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Jurisprudence ProjectDocumento11 páginasMedical Jurisprudence ProjectUtkarshini VermaAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal DeathDocumento15 páginasMaternal DeathSunil PatelAinda não há avaliações

- Moving Beyond Disrespect and Abuse Addressing The Structural Dimensions of Obstetric VioleDocumento10 páginasMoving Beyond Disrespect and Abuse Addressing The Structural Dimensions of Obstetric VioleMaryAinda não há avaliações

- Induced Abortion: ESHRE Capri Workshop GroupDocumento10 páginasInduced Abortion: ESHRE Capri Workshop GroupKepa NeritaAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Abdomen in PregnancyDocumento14 páginasAcute Abdomen in PregnancyNaila WardhanaAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation Proposal 3Documento26 páginasDissertation Proposal 3Dayo TageAinda não há avaliações

- Induced Abortion and Risks That May Impact AdolescentsDocumento29 páginasInduced Abortion and Risks That May Impact AdolescentsMichael RezaAinda não há avaliações

- NIH Public Access: Obesity in Older Adults: Epidemiology and Implications For Disability and DiseaseDocumento6 páginasNIH Public Access: Obesity in Older Adults: Epidemiology and Implications For Disability and DiseaseAniyatul Badi'ahAinda não há avaliações

- Breastfeeding Linked With Long-Term Reduction in ObesityDocumento3 páginasBreastfeeding Linked With Long-Term Reduction in ObesityDea Mustika HapsariAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal Mortality Incidence from AbortionsDocumento7 páginasMaternal Mortality Incidence from AbortionsRichel SuarezAinda não há avaliações

- Efect Abortion Among Preganancy Woman: Newgeneration Unversity Collage Hargaisa SomalilandDocumento33 páginasEfect Abortion Among Preganancy Woman: Newgeneration Unversity Collage Hargaisa SomalilandaadanAinda não há avaliações

- Obesity and Lung Disease: A Guide to ManagementNo EverandObesity and Lung Disease: A Guide to ManagementAnne E. DixonAinda não há avaliações

- Why Aren't There More Maternal Deaths? A Decomposition AnalysisDocumento8 páginasWhy Aren't There More Maternal Deaths? A Decomposition AnalysisFuturesGroup1Ainda não há avaliações

- EASO IFSO EC Guidelines On Metabolic and Bariatric SurgeryDocumento20 páginasEASO IFSO EC Guidelines On Metabolic and Bariatric SurgeryVictor Ivanny DiazAinda não há avaliações

- The UK Rare Diseases FrameworkDocumento38 páginasThe UK Rare Diseases FrameworkuhuhuAinda não há avaliações

- VICTORIA, Cesar - Breastfeeding in The 21st Century - The Lancet PDFDocumento39 páginasVICTORIA, Cesar - Breastfeeding in The 21st Century - The Lancet PDFJorge López GagoAinda não há avaliações

- Tendencia y Causas de La Mortalidad Materna en Chile de 1990 A 2018Documento10 páginasTendencia y Causas de La Mortalidad Materna en Chile de 1990 A 2018Daani LagosAinda não há avaliações

- Evidencs Review StillbirthDocumento17 páginasEvidencs Review StillbirthEdward ManurungAinda não há avaliações

- Eklampsia JurnalDocumento10 páginasEklampsia JurnalmerryAinda não há avaliações

- Pre-Eclampsia Rates in The United States, 1980-2010: Age-Period-Cohort AnalysisDocumento9 páginasPre-Eclampsia Rates in The United States, 1980-2010: Age-Period-Cohort AnalysistiyacyntiaAinda não há avaliações

- Sick Individuals and Sick Population by Rose. GDocumento7 páginasSick Individuals and Sick Population by Rose. GTate SimbaAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal Sepsis and Sepsis ShockDocumento17 páginasMaternal Sepsis and Sepsis ShockAlvaro Andres Flores JimenezAinda não há avaliações

- Testis PDFDocumento8 páginasTestis PDFVlatka MartinovichAinda não há avaliações

- Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths To Make Motherhood Safer: 2006 - 8: A ReviewDocumento6 páginasSaving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths To Make Motherhood Safer: 2006 - 8: A ReviewJHENYAinda não há avaliações

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2021 - Wichmann - Obesity and Gynecological Cancers A Toxic RelationshipDocumento12 páginasIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2021 - Wichmann - Obesity and Gynecological Cancers A Toxic RelationshipLuiza MedeirosAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Basic Epidemiology and Emerging DiseasesDocumento49 páginasIntroduction To Basic Epidemiology and Emerging Diseasesbangtan7svtAinda não há avaliações

- Trees and green spaces slash obesity and depressionDocumento6 páginasTrees and green spaces slash obesity and depressionsarahAinda não há avaliações

- LeyesDocumento10 páginasLeyesmarianaAinda não há avaliações

- Inverse Care LawDocumento8 páginasInverse Care LawHarfieldVillageAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 Reproductive Health EpidemiologyyDocumento13 páginasChapter 1 Reproductive Health EpidemiologyyAnnisa NurrachmawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology PDFDocumento13 páginasBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology PDFdeisy lopezAinda não há avaliações

- Articles: BackgroundDocumento11 páginasArticles: BackgroundshendyAinda não há avaliações

- Too Much Medicine, Too Little BenefitDocumento4 páginasToo Much Medicine, Too Little BenefitJustinAinda não há avaliações

- General Practice in The UK - Background Briefing April 2017Documento8 páginasGeneral Practice in The UK - Background Briefing April 2017RizkaAinda não há avaliações

- UK Obesity Report Analyzes Public Health IssueDocumento14 páginasUK Obesity Report Analyzes Public Health IssueSuman GaihreAinda não há avaliações

- A Guide How To Access and Read Official Government DataDocumento18 páginasA Guide How To Access and Read Official Government DataAmelie Sirio ApuyAinda não há avaliações

- Alyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeDocumento11 páginasAlyshah Abdul Sultan, Joe West, Laila J Tata, Kate M Fleming, Catherine Nelson-Piercy, Matthew J GraingeLuis Gerardo Pérez CastroAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Tests For OetDocumento17 páginasReading Tests For OetJohn Cao72% (29)

- Prenatal Care - Second and Third TrimestersDocumento21 páginasPrenatal Care - Second and Third TrimestersMONSERRAT CERDA LUGOAinda não há avaliações

- Down Syndroms ScreeningDocumento3 páginasDown Syndroms ScreeningAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Hiv and AidsDocumento4 páginasHiv and AidsAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Personality disorders and criminal behavior focus of psychiatric studyDocumento1 páginaPersonality disorders and criminal behavior focus of psychiatric studyAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Child Sexual AbuseDocumento2 páginasChild Sexual AbuseAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Alcohol and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocumento4 páginasAlcohol and Cardiovascular DiseaseAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- HIV Transmisions During SurgeryDocumento1 páginaHIV Transmisions During SurgeryAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Influenza VaccinationDocumento1 páginaInfluenza VaccinationAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Zidovudine in HIVDocumento1 páginaZidovudine in HIVAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Correspondence: Abortion Rates Still RisingDocumento2 páginasCorrespondence: Abortion Rates Still RisingAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Carcinomas Diagnosed: Breast in The 1980sDocumento1 páginaCarcinomas Diagnosed: Breast in The 1980sAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Carcinomas Diagnosed: Breast in The 1980sDocumento1 páginaCarcinomas Diagnosed: Breast in The 1980sAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento7 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Ayu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- World Medical Journal Ed 9Documento32 páginasWorld Medical Journal Ed 9ShalomBinyaminTovAinda não há avaliações

- DocumentDocumento44 páginasDocumentAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Free Mdical in FormationsDocumento95 páginasFree Mdical in FormationsmohammmmadAinda não há avaliações

- Gagal JantungDocumento20 páginasGagal JantungAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal HifemaDocumento10 páginasJurnal HifemaAndi NugrohoAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento7 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Ayu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento6 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Ayu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Somatoform Disordes.Documento9 páginasSomatoform Disordes.Aranda RickAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento6 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669094742') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Ayu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- 08 Anterior Segment Complications of Cataract SurgeryDocumento19 páginas08 Anterior Segment Complications of Cataract SurgeryAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal HifemaDocumento10 páginasJurnal HifemaAndi NugrohoAinda não há avaliações

- Complications of Post PartumDocumento49 páginasComplications of Post PartumNurulAqilahZulkifliAinda não há avaliações

- 08 Anterior Segment Complications of Cataract SurgeryDocumento19 páginas08 Anterior Segment Complications of Cataract SurgeryAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Complications of Post PartumDocumento49 páginasComplications of Post PartumNurulAqilahZulkifliAinda não há avaliações

- Blok 1.5 Kuliah 2. Fisiologi ReproduksiDocumento53 páginasBlok 1.5 Kuliah 2. Fisiologi ReproduksiAyu Ersya WindiraAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Globalization of Human Resource ManagementDocumento12 páginasImpact of Globalization of Human Resource ManagementnishAinda não há avaliações

- Validate Analytical MethodsDocumento9 páginasValidate Analytical MethodsFernando Silva BetimAinda não há avaliações

- BIO125 Syllabus Spring 2020Documento3 páginasBIO125 Syllabus Spring 2020Joncarlo EsquivelAinda não há avaliações

- Open NNDocumento2 páginasOpen NNsophia787Ainda não há avaliações

- FET ExperimentDocumento4 páginasFET ExperimentHayan FadhilAinda não há avaliações

- MNL036Documento22 páginasMNL036husni1031Ainda não há avaliações

- The Chador of God On EarthDocumento14 páginasThe Chador of God On Earthzainabkhann100% (1)

- Task ManagerDocumento2 páginasTask Managersudharan271Ainda não há avaliações

- Indonesian Hotel Annual ReviewDocumento34 páginasIndonesian Hotel Annual ReviewSPHM HospitalityAinda não há avaliações

- Life Orientation September 2022 EngDocumento9 páginasLife Orientation September 2022 EngTondaniAinda não há avaliações

- Early Christian Reliquaries in The Republic of Macedonia - Snežana FilipovaDocumento15 páginasEarly Christian Reliquaries in The Republic of Macedonia - Snežana FilipovaSonjce Marceva50% (2)

- Fracture Mechanics HandbookDocumento27 páginasFracture Mechanics Handbooksathya86online0% (1)

- Replit Ubuntu 20 EnablerDocumento4 páginasReplit Ubuntu 20 EnablerDurval Junior75% (4)

- Controlled Vadose Zone Saturation and Remediation (CVSR)Documento35 páginasControlled Vadose Zone Saturation and Remediation (CVSR)FranciscoGarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Airasia Online Print Tax InvoiceDocumento15 páginasAirasia Online Print Tax InvoiceDarshan DarshanAinda não há avaliações

- 10 (2) Return To Play After Shoulder Instability in National Football League Athletes (Andi Ainun Zulkiah Surur) IIDocumento6 páginas10 (2) Return To Play After Shoulder Instability in National Football League Athletes (Andi Ainun Zulkiah Surur) IIainunAinda não há avaliações

- MSS Command ReferenceDocumento7 páginasMSS Command Referencepaola tixeAinda não há avaliações

- DCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Documento3 páginasDCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Zed Deguzman100% (1)

- 01 035 07 1844Documento2 páginas01 035 07 1844noptunoAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide For Kawabata's "Of Birds and Beasts"Documento3 páginasStudy Guide For Kawabata's "Of Birds and Beasts"BeholdmyswarthyfaceAinda não há avaliações

- Interventional Radiology & AngiographyDocumento45 páginasInterventional Radiology & AngiographyRyBone95Ainda não há avaliações

- Eichhornia Crassipes or Water HyacinthDocumento5 páginasEichhornia Crassipes or Water HyacinthJamilah AbdulmaguidAinda não há avaliações

- Astrolada - Astrology Elements in CompatibilityDocumento6 páginasAstrolada - Astrology Elements in CompatibilitySilviaAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics in ArchaeologyDocumento10 páginasEthics in ArchaeologyAndrei GuevarraAinda não há avaliações

- Worldcom, Inc.: Corporate Bond Issuance: CompanyDocumento14 páginasWorldcom, Inc.: Corporate Bond Issuance: CompanyLe Nguyen Thu UyenAinda não há avaliações

- Detect3D Fire and Gas Mapping Report SAMPLEDocumento29 páginasDetect3D Fire and Gas Mapping Report SAMPLEAnurag BholeAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture Nsche Engr Mafe SIWESDocumento38 páginasLecture Nsche Engr Mafe SIWESoluomo1Ainda não há avaliações

- Dellal ISMJ 2010 Physical and TechnicalDocumento13 páginasDellal ISMJ 2010 Physical and TechnicalagustinbuscagliaAinda não há avaliações

- An Adaptive Memoryless Tag Anti-Collision Protocol For RFID NetworksDocumento3 páginasAn Adaptive Memoryless Tag Anti-Collision Protocol For RFID Networkskinano123Ainda não há avaliações

- Verify File Integrity with MD5 ChecksumDocumento4 páginasVerify File Integrity with MD5 ChecksumSandra GilbertAinda não há avaliações