Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Tim Ingold

Enviado por

Rafael Victorino DevosDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Tim Ingold

Enviado por

Rafael Victorino DevosDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

lo o k i ng for lines

i n n ature

Of slugs and storms

n the mornings, on the flagstones outside our house,

and especially after rain, I often find an intricate tracery

of interlaced trails, as though someone had scribbled

all over them with a slime-pen. They are actually made by

slugs, which come out at night to make their forays into the

vegetation, only to vanish again at dawn into the mysterious

depths from whence they came. In cool wet weather, slugs

may brave the daylight without fear of desiccation, and

we can watch them move. Depositing their rear upon the

ground, they push their front portion forwards against this

posterior resistance. Then, depositing the front in its turn,

they pull up at the rear, repeating the cycle over and over

again in graceful slow motion. This rhythmic, push-pull

cycle seems to me fundamental to the life of most if not all

animate creatures, our human selves included.

Like the slug, we must draw in if we are to issue forth. We

breath in and out, pull one foot up after putting the other

forward. Thus our movement is not, as we might suppose,

the displacement of an already completed being from point

to point, like the move of a chess-piece in play, or of toy

soldiers across an imaginary field of battle. If it were, then

48

EarthLines

T im I ngold

paths could be depicted as orbits or trajectories, calculable

from initial conditions and alterable only through outside

intervention. And by the same token, pauses or moments of

rest would be registered as states of equilibrium, determined

by the balance of external forces. Take your hand off a chesspiece or a toy soldier and it can stay there indefinitely. But we

cannot. As living, respiring beings we find it very difficult to

stay completely still. It is like holding ones breath, creating

an inner tension that grows ever more intense the longer it

lasts. And our feeling is that when we move, we body forth

along the path of our own movement: a path, that is, of

growth and becoming.

Consider the movements of the whirlwind or storm.

We might say that it strikes first here and then there, and

the meteorologist might try to plot its course. But the storm

is not a coherent, self-contained entity that displaces from

point to point across the sky. It is rather a movement in

itself, a winding up that creates a point of stillness at its

eye. As it winds up on its advancing front, it unwinds on the

retreat. But is it any different with the slug? In his Creative

Evolution of 1911, the philosopher Henri Bergson1 argued

that every organism is cast like an eddy in the current of

life. It is as though, in its development, it describes a kind

November 2012

of circle. The living being that has thus spiralled in on itself

presents only the semblance of an externally bounded object.

Once we realise, however, that its outward form is but the

envelope of a movement, then storm and slug begin to look

remarkably similar. As the storm winds and unwinds, leaving

a trail of destruction, if it is severe across the surface of

the earth, so the slug alternately pushes forth and pulls up,

leaving its slime trails on the ground. They may operate at

vastly different scales, but the principle is the same.

The meshwork

The beautiful tracery of slime trails on the flagstones comprises

what I call a meshwork.2 By this I mean an entanglement of

interwoven lines. These lines may loop or twist around one

another, or weave in and out. Crucially, however, they do

not connect. This is what distinguishes the meshwork from

the network. The lines of the network are connectors: each

is given as the relation between points, independently and in

advance of any movement from one towards the other. Such

lines therefore lack duration: the network is a purely spatial

construct. The lines of the meshwork, by contrast, are of

movement or growth. They are the lines along which things

become. Every animate being, as it threads its way through

and among the ways of every other, must perforce improvise

a passage, and in so doing it lays another line. We can do

the same. From a distance, the meshwork might look like a

matted surface. Up close, however, as if our eyes were next

to our fingernails or toenails, we find ourselves entangled in

a system of sympathies and longings, with no dots whatever,

just lines, all curving, shooting in and out of knot stations

consisting of all kinds of textile art: braids, knots of every

type, loops, crossings and interlaces.3

These words are taken from a remarkable new book by

the architectural and design theorist, Lars Spuybroek. As he

intimates here, where the network has nodes, the meshwork

has knots. Knots are places where many lines of becoming

are drawn tightly together. Yet every line overtakes the knot

in which it is tied. Its end is always loose, somewhere beyond

the knot, where it is groping towards an entanglement with

other lines, in other knots. What is life, indeed, if not a

proliferation of loose ends! It can only be carried on in a

world that is not fully joined up. Thus the very continuity of

life its sustainability, in current jargon depends on the

fact that nothing ever quite fits. The world is not assembled

like a jig-saw puzzle in which every building block slots

perfectly into place within an already pre-ordained totality.

To be sure, we are always being told these days that the world

we inhabit is built from blocks: thus biologists speak of the

building blocks of cellular organisms, psychologists of the

building blocks of thought, physicists of the building blocks

of the universe itself. But a world built from perfectly fitting

blocks could harbour no life at all. The reality is more akin to

a quilt in which ill-fitting elements are sewn together along

irregular edges to form a covering that is always provisional,

as elements can at any time be added or taken away.

Philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Flix

Guattari take up the history of the quilt in developing their

idea of a topology that is smooth rather than striated, showing

how early embroidered fabrics gave way to a patchwork

Issue 3

technique where scraps of leftover material or fragments

salvaged from worn-out garments were sewn together. With

its regular and rectilinear intersections of woof and weft,

fabric for Deleuze and Guattari is the epitome of the

striated. But in the patchwork, an amorphous collection of

juxtaposed pieces that can be joined together in an infinite

number of ways, the principle of striation is subordinated

to that of the smooth. No material better exemplifies the

principle of the smooth, however, than felt. Comprised of

a mlange of entangled woollen fibres, with no consistent

direction and extending without limit and in all directions,

felt say Deleuze and Guattari is everything that fabric

is not. It is an anti-fabric.4 Could the same, then, not be

said of the meshwork? Are the wayward trails left by slugs

in their nocturnal meanderings not comparable to the

fibres of felt, which in turn seem reminiscent of the tracks

worn in the ground, in their pastoral wanderings, by the

very sheep upon whose backs the wool was grown? This is

indeed what Deleuze and Guattari would have us believe.

Yet the constitutive lines of the smooth, they say, are abstract,

as distinct from lines that are either geometric or organic.

In order to appreciate what they are getting at, we need to

examine these three kinds of line a little more closely.

Geometric and organic lines

We begin with the line of geometry the Euclidean line

defined as the connection between two points. As its name

implies, the geometric line has its origin in the practices by

which the surveyors of ancient Egypt measured the earth

after every annual flood of the Nile. They would stretch a

cord between stakes hammered in the ground. From this, as

philosopher Michel Serres reminds us, comes the legal notion

of contract: a cord that draws or tracts us together.5 The

stretched cord, string or thread, however, retains a certain

tactility: you can feel the tension; pluck it, and it vibrates. As

textile artist Victoria Mitchell has put it, taut thread is a kind

of hinge between feeling and form, between bodily kinesis

and speculative reason.6 But as geometry was drawn into the

art and science of optics, and as the earth-measurers cord

was joined by the optical instruments of the seafarer, the

once tangible, taut thread morphed into its intangible and

insensible spectre, the ray of light.

For long, both thread and ray, the material line and

its spectral double, appeared together, like a thing and its

shadow. Setting out the principles of perspective at the

dawn of the Renaissance, in his On Painting, Leon Battista

Alberti thought of lines of sight as threads, like those of a

veil stretched between the eye and the thing seen, yet so fine

that they could not be split.7 But as a vector of projection,

the geometric line was eventually divested of all remnants

of tactility. In making connections and setting limits, this

line lies at the root of law, reason and analytic thought. It is

laconic and always to the point. Organic lines, by contrast,

trace the envelopes or contours of things as though they

were contained within them: they are outlines. They are also

separators, dividing the surfaces on which they are drawn

between what is on one side of the line and what is on the

other: in this sense they are analogous to cuts.

Such lines, however, have no presence on or in the things

EarthLines

49

The abstract line

themselves. I might draw an egg in outline as an oval, the trunk

of a tree as two parallel lines or the sky as an arc, but would

look in vain to find their counterparts on egg or trunk, or in

the heavens. I might try to draw a cloud using curling or wispy

lines, but there are no such lines lurking in the cloud itself,

waiting to ensnare unsuspecting aircraft. I might want to draw

an apple or the border between a meadow and a ploughed

field, yet as the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes

in his essay Eye and Mind (1964: 182), I would be deluded to

think that the outer contour of the apple or the field boundary

is actually present, such that, guided by points taken from the

real world, the pencil or brush would only have to pass over

them.8 For if we look, there are no lines to be seen.

This and similar observations have led numerous authorities

to conclude that there are no lines in nature, and therefore that

the lines of drawing have only a symbolic connection to

their referents, based on artifice or convention rather than

phenomenal experience. The philosopher Patrick Maynard has

catalogued a series of statements to this effect.9 Lines? I see no

lines! the great Goya, himself a consummate draughtsman, is

reputed to have exclaimed. They are impositions of the mind

upon reality, he thought, not present in what one sees. And

in her recent, magisterial survey of histories and theories of

drawing practice, artist and curator Deanna Petherbridge

concurs. Line itself, she emphasises, does not exist in the

observable world. Line is a representational convention10

50

EarthLines

In short, if the geometric line is the mark of reason,

then the outline looks more like a cultural construct:

the visible expression of a process by which the mind,

according to a well-worn anthropological paradigm, more

or less arbitrarily divides the continuum of nature into

discrete objects that can be identified and named. The

lines of those familiar join-the-dot puzzles, designed

for children, manage to be both geometric and organic

simultaneously, at once connecting points and outlining

objects. Rather as children join the dots, surveyors make

maps, outlining such features as riverbanks and coasts.

But the lines of the meshwork such as the slime-trails

of slugs or the paths of storms are not outlines, nor are

they point-to-point connectors. To my eyes, however, they

seem entirely real and indeed natural. If we allow the

trace of a graphite pencil on paper to be a line, then why

can we not also allow the trail of a slug on a flagstone?

Surely, there are lines in the observable world, for they

are unmistakably there. In what conceivable sense, then,

can they be said to be abstract?

For an answer we can turn to the writings of the great

pioneer of modern abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky. In

an essay On the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky insists that

abstraction does not mean draining a work of content so

as to leave only an empty outline or a pure geometrical

form. On the contrary, it means removing all those

figurative elements that refer only to the externalities

of things that is, to their outward appearances in

order to reveal what he called their inner necessity.11 By

this he meant the life force that animates them and that,

since it animates us too, allows us to join with them and

experience their affects and pulsations from within.

In a charming sketch penned in 1935, Kandinsky12

asks us to consider the similarities and differences

between a line and a fish. They do have certain things in

common: both are animated by forces internal to them

that find expression in the linear quality of movement. A

fish streaking through the water could be a line. Yet the

fish remains a creature of the external world a world

of organisms and their environments and depends

on this world to exist. The line, by contrast, does not.

The line is no more, and no less, than life itself. That,

says Kandinsky, is why he prefers the line to the fish,

at least in his painting. And this, too, is why Deleuze

and Guattari, following Kandinsky, can say of a line that

delimits nothing, that describes no contour, that no longer

goes from point to point but passes between points,

that is without outside or inside, form or background,

beginning or end and that is alive as a continuous

variation, that it is abstract.13

Such is the line of the river current, or of the ebb

and flow of the tide, as distinct from the riverbank or

coastline plotted on the cartographers chart. In words

attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, Merleau-Ponty writes

that the secret of drawing any thing is to discover the

particular way in which a certain flexuous line, which

is, so to speak, its generating axis, is directed through its

November 2012

whole extent. Such a line, he continues, is neither here nor

there, neither in this place nor that, but always between or

behind whatever we fix our eyes upon.14 One could almost

treat line as a verb, and say that in the things growing in

its issuing forth, in its making itself visible, as the painter

Paul Klee15 would say it lines.

1 Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. A. Mitchell. London:

Macmillan, 1911, page 134.

Awful lines

4 Gilles Deleuze and Flix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus:

Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. B. Massumi. London:

Continuum, 2004, page 525.

That would certainly accord with the view of the

nineteenth-century critic John Ruskin. In his massive threevolume compendium The Stones of Venice (1851-53), Ruskin

assembled a collection of what he called abstract lines into

a single figure, combining his observations of things great

and small, from a glacier and a mountain ridge, through

a spruce bough, to a willow leaf and a nautilus shell (see

figure, opposite). In every case, he contended, the line is

expressive of action or force of some kind.16 These lines of

action and force, as he would go on to explain in his treatise

of 1857 on The Elements of Drawing, are to be discerned in

the animal in its motion, the tree in its growth, the cloud

in its course, the mountain in its wearing away. Thus he

went on to advise the novice: try always, whenever you

look at a form, to see the lines in it which have had power

over its past fate and will have power over its futurity. Those

are its awful lines; see that you seize on those, whatever else

you miss.17

Wisdom, for Ruskin, lay in grasping not just the way things

are but the way they are going, and this meant concentrating

not on the outlines of shape but on the centrelines of force.

These are the awful lines. If they abstract from the real it

is not by reduction but by the precise registration of its

variation. The awesome power of such lines lies precisely in

their capacity to break the bounds that otherwise hold things

captive within their envelopes, thus releasing them into the

fullness of their being. Such are the lines that comprise the

meshwork and that, for Deleuze and Guattari, constitute

the topology of the smooth. It is a topology, they argue, that

relies not on points that might be connected geometrically,

nor on objects that might be outlined organically, but on

the tactile and sonorous qualities of a world of wind and

weather, where there is no horizon separating earth and sky,

no intermediate distance, no perspective or contour.18

This is the world of slugs and storms, of winding trails

and swirling winds, of earth and sky. It is not a landscape,

in which everything is set out on the ground like objects

and scenery on the stage, ready and waiting for the action

to begin. In the landscape, the geometric line defines the

disposition of elements and the organic line delimits their

represented shapes and forms. The abstract line, however,

anticipates the growth of things in an earth-sky world. In

such a world, lines are not imposed by representational

convention, nor are they plotted between points. They

are rather laid down in movement. Look at nature, as

landscape, and there are no lines to be seen. They exist

only in its graphic representations. Look with it, however, as

earth and sky, join in the movements of its formation, and

lines are everywhere. They are the very lines along which we

and other organisms live. r

Issue 3

2 Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays in Movement, Knowledge and

Description. London: Routledge, 2011, pages 63-94.

3 Lars Spuybroek, The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of

Design. Rotterdam: V2_Publishing, 2011, page 321

5 Michel Serres, The Natural Contract, trans. E. MacArthur and

W. Paulson. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995,

page 59.

6 Victoria Mitchell, Drawing threads from sight to site, Textile

4(3): 340-361, 2006, page 345.

7 Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, trans. C. Grayson, ed. M.

Kemp, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972, page 38.

8 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Eye and mind, trans. C. Dallery,

in The Primacy of Perception, and Other Essays on Phenomenological

Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics, ed. J. M. Edie,

Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, pp.159-190, 1964,

page 182.

9 Patrick Maynard, Drawing Distinctions: The Varieties of Graphic

Expression. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005, page 99.

10 Deanna Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and

Theories of Practice, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010,

page 90.

11 Wassily Kandinsky, Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, Vols.

1 (1901-1921) and 2 (1922-1943), eds. K. C. Lindsay and P. Vergo.

London: Faber & Faber, 1982, page 160.

12 Kandinsky, op. cit. pages 774-5.

13 Deleuze and Guattari, op. cit. pages 549, 550-1 fn. 38.

14 Merleau-Ponty, op. cit. page 183.

15 Paul Klee, Notebooks, Volume 1: The Thinking Eye, ed. J. Spiller,

trans. R. Manheim. London: Lund Humphries, 1961, page 76.

16 John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Volume 1, The Foundations

(Volume 9 of The Works of John Ruskin, eds. E. T. Cook and A.

Wedderburn). London: George Allen, 1903, page 268.

17 John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing (Volume 15 of The Works

of John Ruskin, eds. E. T. Cook and A. Wedderburn). London:

George Allen, 1904, page 91.

18 Deleuze and Guattari, op. cit. page 421.

Tim Ingold is Professor of Social Anthropology at the

University of Aberdeen. He has carried out ethnographic

fieldwork in Lapland, and has written on environment,

technology and social organisation in the circumpolar North,

on evolutionary theory in anthropology, biology and history,

on the role of animals in human society, on language and tool

use, and on environmental perception and skilled practice.

He is currently exploring issues on the interface between

anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. His latest

book, Being Alive, was published by Routledge in 2011.

Photographs by Tim Ingold.

EarthLines

51

Você também pode gostar

- Tim Ingold Up Down and AlongDocumento10 páginasTim Ingold Up Down and AlongEdilvan Moraes LunaAinda não há avaliações

- The Inbetweenness of ThingsDocumento25 páginasThe Inbetweenness of ThingsShahil AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- Panofsky, Style and Medium in Motion PicturesDocumento18 páginasPanofsky, Style and Medium in Motion Picturesnicolajvandermeulen100% (2)

- Gabriel Rockhill Philip Watts (Ed) - Jacques Rancière. History, Politics, AestheticsDocumento369 páginasGabriel Rockhill Philip Watts (Ed) - Jacques Rancière. History, Politics, Aestheticscrispasion100% (4)

- Carroll, N. (1985) Medium Specificity Arguments PDFDocumento14 páginasCarroll, N. (1985) Medium Specificity Arguments PDFpaologranataAinda não há avaliações

- Feminist New MaterialismsDocumento118 páginasFeminist New MaterialismsjpcoteAinda não há avaliações

- Transmedium: Conceptualism 2.0 and the New Object ArtNo EverandTransmedium: Conceptualism 2.0 and the New Object ArtAinda não há avaliações

- Geoffrey Batchen, "Phantasm: Digital Imaging and The Death of Photography." in Edward A Shanken Ed, Art and Electronic Media (Phaidon, 2009), 209-211.Documento7 páginasGeoffrey Batchen, "Phantasm: Digital Imaging and The Death of Photography." in Edward A Shanken Ed, Art and Electronic Media (Phaidon, 2009), 209-211.Forest of Fools100% (1)

- Derrida, Jacques - Athens, Still Remains (Fordham, 2010)Documento87 páginasDerrida, Jacques - Athens, Still Remains (Fordham, 2010)Bruno LeónAinda não há avaliações

- Mitchell, W.T.J. - The Pictorial TurnDocumento27 páginasMitchell, W.T.J. - The Pictorial TurnMadi Manolache87% (23)

- OlafurSublime Dissertation New PDFDocumento42 páginasOlafurSublime Dissertation New PDFMatyas CsiszarAinda não há avaliações

- Art, Common Sense and Photography - Victor BurginDocumento10 páginasArt, Common Sense and Photography - Victor BurginOlgu Kundakçı100% (1)

- Laura U Marks Touch Sensuous Theory and Multisensory MediaDocumento283 páginasLaura U Marks Touch Sensuous Theory and Multisensory MediaSangue CorsárioAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary Post Studio Art Practice and Its Institutional CurrencyDocumento57 páginasContemporary Post Studio Art Practice and Its Institutional CurrencyNicolás Lamas100% (1)

- E. The Duchamp Effect - Hal FosterDocumento29 páginasE. The Duchamp Effect - Hal FosterDavid López100% (1)

- An Archeology of A Computer Screen Lev ManovichDocumento25 páginasAn Archeology of A Computer Screen Lev ManovichAna ZarkovicAinda não há avaliações

- Why I Fell For Assemblages: A Response To CommentsDocumento9 páginasWhy I Fell For Assemblages: A Response To Commentsi_pistikAinda não há avaliações

- Robert Wilson NotesDocumento7 páginasRobert Wilson NotesNatashia Trillin' MarshallAinda não há avaliações

- Some Relations Between Conceptual and Performance Art, FrazerDocumento6 páginasSome Relations Between Conceptual and Performance Art, FrazerSabiha FarhatAinda não há avaliações

- Aesthetics of AffectDocumento11 páginasAesthetics of Affectwz100% (1)

- The Accident of ArtDocumento7 páginasThe Accident of ArtElsa OviedoAinda não há avaliações

- Gustavo Fares Painting in The Expanded FieldDocumento11 páginasGustavo Fares Painting in The Expanded FieldAdam BergeronAinda não há avaliações

- Nancy IntruderDocumento8 páginasNancy IntruderXiaoda WangAinda não há avaliações

- Jones, Amelia - Women in DadaDocumento13 páginasJones, Amelia - Women in DadaΚωνσταντινος ΖησηςAinda não há avaliações

- Artistic Research As Boundary Work1 Henk BorgdorffDocumento7 páginasArtistic Research As Boundary Work1 Henk BorgdorffBrita LemmensAinda não há avaliações

- Claire Bishop - Digital Divide On Contemporary Art and New MediaDocumento23 páginasClaire Bishop - Digital Divide On Contemporary Art and New MediaPedro Veneroso100% (1)

- Latour - What Is The Style of Matters of ConcernDocumento27 páginasLatour - What Is The Style of Matters of ConcerngodofredopereiraAinda não há avaliações

- Research/Artist Statement 2016Documento3 páginasResearch/Artist Statement 2016John Opera100% (1)

- Bazin, A. - Death Every AfternoonDocumento6 páginasBazin, A. - Death Every AfternoonMaringuiAinda não há avaliações

- The Aesthetic ExperienceDocumento12 páginasThe Aesthetic ExperienceA.S.WAinda não há avaliações

- Hybrid Walking As Art Approaches and ArtDocumento8 páginasHybrid Walking As Art Approaches and ArtAlok MandalAinda não há avaliações

- Benjamin Buchloh Detritus and DecrepitudeDocumento16 páginasBenjamin Buchloh Detritus and DecrepitudeinsulsusAinda não há avaliações

- Bazin On MarkerDocumento2 páginasBazin On Markerlu2222100% (1)

- Precarious Constructions - Nicolas BourriaudDocumento8 páginasPrecarious Constructions - Nicolas BourriaudElif DemirkayaAinda não há avaliações

- Bodily Functions in Performance: A Study Room Guide On Shit, Piss, Blood, Sweat and Tears (2013)Documento39 páginasBodily Functions in Performance: A Study Room Guide On Shit, Piss, Blood, Sweat and Tears (2013)thisisLiveArt100% (1)

- Voiding CinemaDocumento22 páginasVoiding CinemaMario RighettiAinda não há avaliações

- Moving Lips - Cinema As VentriloquismDocumento14 páginasMoving Lips - Cinema As VentriloquismArmando Carrieri100% (1)

- Artistic Research WholeDocumento186 páginasArtistic Research WholeJuan Guillermo Caicedo DiazdelCastilloAinda não há avaliações

- Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and MediaNo EverandSurface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and MediaNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Deleuze and SpaceDocumento129 páginasDeleuze and SpaceNick Jensen100% (6)

- Babette Film in Social Context: Reading For Class #5Documento9 páginasBabette Film in Social Context: Reading For Class #5monaflorianAinda não há avaliações

- Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction - Art History Unstuffed PDFDocumento5 páginasJacques Derrida and Deconstruction - Art History Unstuffed PDFJosé Manuel Bueso Fernández100% (1)

- Demos Decolonizing Nature Intro 2016.compressedDocumento15 páginasDemos Decolonizing Nature Intro 2016.compressedIrene Depetris-ChauvinAinda não há avaliações

- Experience in Interactive ArtDocumento21 páginasExperience in Interactive ArtJakub Grosz100% (6)

- M J Mondzain Homo Spectator Introduction 2007 (Eng)Documento6 páginasM J Mondzain Homo Spectator Introduction 2007 (Eng)claraAinda não há avaliações

- Erin Manning Politics of Touch Sense, Movement, Sovereignty 2006Documento222 páginasErin Manning Politics of Touch Sense, Movement, Sovereignty 2006Marek Schwarzenegger100% (1)

- Marc-Auge-Non Place in The Age of Spaces of FlowDocumento23 páginasMarc-Auge-Non Place in The Age of Spaces of FlowEla TudorAinda não há avaliações

- The Future of The ImageDocumento73 páginasThe Future of The ImageMarta MendesAinda não há avaliações

- Helene Frichot Creative Ecologies Theorizing The Practice of Architecture 1Documento265 páginasHelene Frichot Creative Ecologies Theorizing The Practice of Architecture 1enantiomorpheAinda não há avaliações

- On Art's Romance With Design - Alex ColesDocumento8 páginasOn Art's Romance With Design - Alex ColesJohn Balbino100% (2)

- On Slowness - Lutz KoepnickDocumento38 páginasOn Slowness - Lutz KoepnickJuan Alberto CondeAinda não há avaliações

- Cyborgian Images: The Moving Image between Apparatus and BodyNo EverandCyborgian Images: The Moving Image between Apparatus and BodyAinda não há avaliações

- George Marcus - The Traffic in MontageDocumento6 páginasGeorge Marcus - The Traffic in MontageRafael Victorino DevosAinda não há avaliações

- Hans BeltingDocumento12 páginasHans BeltingRafael Victorino Devos100% (1)

- Taussig Physiognomic Aspects of Social Worldsmichael TaussigDocumento14 páginasTaussig Physiognomic Aspects of Social Worldsmichael TaussigRafael Victorino DevosAinda não há avaliações

- Hutchins CognitionDocumento5 páginasHutchins CognitionRafael Victorino DevosAinda não há avaliações

- Paris, Invisible City: The Plasma: City, Culture and SocietyDocumento3 páginasParis, Invisible City: The Plasma: City, Culture and SocietyRafael Victorino DevosAinda não há avaliações

- Britten's Musical Language, by Philip RupprechtDocumento370 páginasBritten's Musical Language, by Philip Rupprechtheriberto100% (3)

- Fundamental Concepts of VideoDocumento55 páginasFundamental Concepts of VideoAwaisAdnan100% (2)

- Dish TVDocumento97 páginasDish TVashishjain4848Ainda não há avaliações

- Case StudyDocumento4 páginasCase StudyNATASHA SINGHANIAAinda não há avaliações

- Vipassana Meditation CenterDocumento37 páginasVipassana Meditation CenterOvais AnsariAinda não há avaliações

- PUMA Promotions PDFDocumento13 páginasPUMA Promotions PDFVishnu Ruban75% (4)

- Maging Akin Muli: A Film Analysis by As Required byDocumento1 páginaMaging Akin Muli: A Film Analysis by As Required byPaolo Enrino PascualAinda não há avaliações

- Schaff, Wace. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of The Christian Church. Second Series. 1894. Volume 11.Documento664 páginasSchaff, Wace. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of The Christian Church. Second Series. 1894. Volume 11.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Mo JaresDocumento3 páginasMo JaresGr MacopiaAinda não há avaliações

- Acoustic Soloist As80rDocumento6 páginasAcoustic Soloist As80rPatrick AliAinda não há avaliações

- Lista Preturi Alfaparf RO 2010 IanDocumento7 páginasLista Preturi Alfaparf RO 2010 Ianmilogu69Ainda não há avaliações

- Examination of ConscienceDocumento2 páginasExamination of Consciencetonos8783Ainda não há avaliações

- Capote - The Walls Are Cold PDFDocumento5 páginasCapote - The Walls Are Cold PDFJulian Mancipe AcuñaAinda não há avaliações

- Shirk Kufr NifaqDocumento8 páginasShirk Kufr NifaqbanjiniAinda não há avaliações

- Durst Rho 600 Pictor - SM - 4-HeadAdjustment - V1.3 - 1Documento25 páginasDurst Rho 600 Pictor - SM - 4-HeadAdjustment - V1.3 - 1Anonymous aPZADS4Ainda não há avaliações

- Second Conditional Fun Activities Games Grammar Guides Oneonone Activ - 125322Documento9 páginasSecond Conditional Fun Activities Games Grammar Guides Oneonone Activ - 125322Mark-Shelly BalolongAinda não há avaliações

- TDS TDS 483 Jotafloor+Damp+Bond Euk GBDocumento4 páginasTDS TDS 483 Jotafloor+Damp+Bond Euk GBTuan ThanAinda não há avaliações

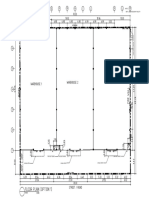

- Floor Plan (Option 1) : Warehouse 2 Warehouse 1 Warehouse 3Documento1 páginaFloor Plan (Option 1) : Warehouse 2 Warehouse 1 Warehouse 3John Carlo AmodiaAinda não há avaliações

- An Analysis of Stephen Dedalus in A Portrait of The Artist As A YoungDocumento4 páginasAn Analysis of Stephen Dedalus in A Portrait of The Artist As A YoungSeabiscuit NygmaAinda não há avaliações

- Rudiment Control: Clinic Edition!Documento28 páginasRudiment Control: Clinic Edition!USER58679100% (2)

- Đề Tuyển Sinh Lớp 10 Môn Tiếng AnhDocumento6 páginasĐề Tuyển Sinh Lớp 10 Môn Tiếng Anhvo nguyen thanh tranhAinda não há avaliações

- Amelia Spokes Warwick Primary School Wellingborough NorthamptonshireDocumento4 páginasAmelia Spokes Warwick Primary School Wellingborough NorthamptonshireDiamonds Study CentreAinda não há avaliações

- Esl Student Book1 PDFDocumento382 páginasEsl Student Book1 PDFSayoto Amoroso HermieAinda não há avaliações

- Ticket To RideDocumento4 páginasTicket To RideEdgar MalagónAinda não há avaliações

- Nitobond EP TDSDocumento2 páginasNitobond EP TDSengr_nhelAinda não há avaliações

- G-Worksheet 4Documento5 páginasG-Worksheet 4Sayandeep MitraAinda não há avaliações

- Celtic Wrestling The Jacket StylesDocumento183 páginasCeltic Wrestling The Jacket StylesMethleigh100% (3)

- Tata Nano Case StudyDocumento9 páginasTata Nano Case StudyShilpa Sehrawat0% (1)

- Himachal Report A3 Low LowDocumento43 páginasHimachal Report A3 Low Lowapi-241074820Ainda não há avaliações

- SMART VILLA RevisedDocumento9 páginasSMART VILLA RevisedAanie FaisalAinda não há avaliações