Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 1: Prelim Exam Coverage - Cases

Enviado por

mccm92Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 1: Prelim Exam Coverage - Cases

Enviado por

mccm92Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

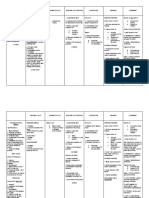

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty.

Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 1

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

CITIZENSHIP REQUIREMENT

For Individuals

RAMIREZ v. VDA. DE RAMIREZ

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. L-27952

February 15, 1982

TESTATE ESTATE OF JOSE EUGENIO RAMIREZ,

MARIA LUISA PALACIOS, Administratrix, petitionerappellee,

vs.

MARCELLE D. VDA. DE RAMIREZ, ET AL.,

oppositors, JORGE and ROBERTO

RAMIREZ, legatees, oppositors- appellants.

ABAD SANTOS, J.:

The main issue in this appeal is the manner of

partitioning the testate estate of Jose Eugenio Ramirez

among the principal beneficiaries, namely: his widow

Marcelle Demoron de Ramirez; his two grandnephews

Roberto and Jorge Ramirez; and his companion

Wanda de Wrobleski.

The task is not trouble-free because the widow

Marcelle is a French who lives in Paris, while the

companion Wanda is an Austrian who lives in Spain.

Moreover, the testator provided for substitutions.

Jose Eugenio Ramirez, a Filipino national, died in

Spain on December 11, 1964, with only his widow as

compulsory heir. His will was admitted to probate by

the Court of First Instance of Manila, Branch X, on July

27, 1965. Maria Luisa Palacios was appointed

administratrix of the estate. In due time she submitted

an inventory of the estate as follows:

XXX

XXX

XXX

On June 23, 1966, the administratrix submitted a

project of partition as follows: the property of the

deceased is to be divided into two parts. One part shall

go to the widow 'en pleno dominio" in satisfaction of

her legitime; the other part or "free portion" shall go to

Jorge and Roberto Ramirez "en nuda propriedad."

Furthermore, one third (1/3) of the free portion is

charged with the widow's usufruct and the remaining

two-thirds (2/3) with a usufruct in favor of Wanda.

Jorge and Roberto opposed the project of partition on

the grounds: (a) that the provisions for vulgar

substitution in favor of Wanda de Wrobleski with

respect to the widow's usufruct and in favor of Juan

Pablo Jankowski and Horacio V. Ramirez, with respect

to Wanda's usufruct are invalid because the first heirs

Marcelle and Wanda) survived the testator; (b) that the

provisions for fideicommissary substitutions are also

invalid because the first heirs are not related to the

second heirs or substitutes within the first degree, as

provided in Article 863 of the Civil Code; (c) that the

grant of a usufruct over real property in the Philippines

in favor of Wanda Wrobleski, who is an alien, violates

Section 5, Article III of the Philippine Constitution; and

that (d) the proposed partition of the testator's interest

in the Santa Cruz (Escolta) Building between the

widow Marcelle and the appellants, violates the

testator's express win to give this property to them

Nonetheless, the lower court approved the project of

partition in its order dated May 3, 1967. It is this order

which Jorge and Roberto have appealed to this Court.

1. The widow's legitime.

The appellant's do not question the legality of giving

Marcelle one-half of the estate in full ownership. They

admit that the testator's dispositions impaired his

widow's legitime. Indeed, under Art. 900 of the Civil

Code "If the only survivor is the widow or widower, she

or he shall be entitled to one-half of the hereditary

estate." And since Marcelle alone survived the

deceased, she is entitled to one-half of his estate over

which he could impose no burden, encumbrance,

condition or substitution of any kind whatsoever. (Art.

904, par. 2, Civil Code.)

It is the one-third usufruct over the free portion which

the appellants question and justifiably so. It appears

that the court a quo approved the usufruct in favor of

Marcelle because the testament provides for a usufruct

in her favor of one-third of the estate. The court a

quo erred for Marcelle who is entitled to one-half of the

estate "en pleno dominio" as her legitime and which is

more than what she is given under the will is not

entitled to have any additional share in the estate. To

give Marcelle more than her legitime will run counter to

the testator's intention for as stated above his

dispositions even impaired her legitime and tended to

favor Wanda.

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 2

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

2. The substitutions.

It may be useful to recall that "Substitution is the

appoint- judgment of another heir so that he may enter

into the inheritance in default of the heir originally

instituted." (Art. 857, Civil Code. And that there are

several kinds of substitutions, namely: simple or

common, brief or compendious, reciprocal, and

fideicommissary (Art. 858, Civil Code.) According to

Tolentino, "Although the Code enumerates four

classes, there are really only two principal classes of

substitutions: the simple and the fideicommissary. The

others are merely variations of these two." (111 Civil

Code, p. 185 [1973].)

The simple or vulgar is that provided in Art. 859 of the

Civil Code which reads:

ART. 859. The testator may designate one or more

persons to substitute the heir or heirs instituted in case

such heir or heirs should die before him, or should not

wish, or should be incapacitated to accept the

inheritance.

A simple substitution, without a statement of the cases

to which it refers, shall comprise the three mentioned

in the preceding paragraph, unless the testator has

otherwise provided.

The fideicommissary substitution is described in the

Civil Code as follows:

ART. 863. A fideicommissary substitution by virtue of

which the fiduciary or first heir instituted is entrusted

with the obligation to preserve and to transmit to a

second heir the whole or part of inheritance, shall be

valid and shall take effect, provided such substitution

does not go beyond one degree from the heir originally

instituted, and provided further that the fiduciary or first

heir and the second heir are living at time of the death

of the testator.

It will be noted that the testator provided for a vulgar

substitution in respect of the legacies of Roberto and

Jorge Ramirez, the appellants, thus: con sustitucion

vulgar a favor de sus respectivos descendientes, y, en

su defecto, con substitution vulgar reciprocal entre

ambos.

The appellants do not question the legality of the

substitution so provided. The appellants question the

sustitucion vulgar y fideicomisaria a favor de Da.

Wanda de Wrobleski" in connection with the one-third

usufruct over the estate given to the widow Marcelle

However, this question has become moot because as

We have ruled above, the widow is not entitled to any

usufruct.

The appellants also question the sustitucion vulgar y

fideicomisaria in connection with Wanda's usufruct

over two thirds of the estate in favor of Juan Pablo

Jankowski and Horace v. Ramirez.

They allege that the substitution in its vulgar aspect as

void because Wanda survived the testator or stated

differently because she did not predecease the

testator. But dying before the testator is not the only

case for vulgar substitution for it also includes refusal

or incapacity to accept the inheritance as provided in

Art. 859 of the Civil Code, supra. Hence, the vulgar

substitution is valid.

As regards the substitution in its fideicommissary

aspect, the appellants are correct in their claim that it

is void for the following reasons:

(a) The substitutes (Juan Pablo Jankowski and Horace

V. Ramirez) are not related to Wanda, the heir

originally instituted. Art. 863 of the Civil Code validates

a fideicommissary substitution "provided such

substitution does not go beyond one degree from the

heir originally instituted."

What is meant by "one degree" from the first heir is

explained by Tolentino as follows:

Scaevola Maura, and Traviesas construe "degree" as

designation, substitution, or transmission. The

Supreme Court of Spain has decidedly adopted this

construction. From this point of view, there can be only

one tranmission or substitution, and the substitute

need not be related to the first heir. Manresa, Morell

and Sanchez Roman, however, construe the word

"degree" as generation, and the present Code has

obviously followed this interpretation. by providing that

the substitution shall not go beyond one degree "from

the heir originally instituted." The Code thus clearly

indicates that the second heir must be related to and

be one generation from the first heir.

From this, it follows that the fideicommissary can only

be either a child or a parent of the first heir. These are

the only relatives who are one generation or degree

from the fiduciary (Op. cit., pp. 193-194.)

(b) There is no absolute duty imposed on Wanda to

transmit the usufruct to the substitutes as required by

Arts. 865 and 867 of the Civil Code. In fact, the

appellee admits "that the testator contradicts the

establishment of a fideicommissary substitution when

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 3

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

he permits the properties subject of the usufruct to be

sold upon mutual agreement of the usufructuaries and

the naked owners." (Brief, p. 26.)

PHIL. BANKING v. LUI SHE

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

3. The usufruct of Wanda.

The appellants claim that the usufruct over real

properties of the estate in favor of Wanda is void

because it violates the constitutional prohibition

against the acquisition of lands by aliens.

The 1935 Constitution which is controlling provides as

follows:

SEC. 5. Save in cases of hereditary succession, no

private agricultural land shall be transferred or

assigned except to individuals, corporations, or

associations qualified to acquire or hold lands of the

public domain in the Philippines. (Art. XIII.)

The court a quo upheld the validity of the usufruct

given to Wanda on the ground that the Constitution

covers not only succession by operation of law but

also testamentary succession. We are of the opinion

that the Constitutional provision which enables aliens

to acquire private lands does not extend to

testamentary succession for otherwise the prohibition

will be for naught and meaningless. Any alien would be

able to circumvent the prohibition by paying money to

a Philippine landowner in exchange for a devise of a

piece of land.

This opinion notwithstanding, We uphold the usufruct

in favor of Wanda because a usufruct, albeit a real

right, does not vest title to the land in the usufructuary

and it is the vesting of title to land in favor of aliens

which is proscribed by the Constitution.

IN VIEW OF THE FOREGOING, the estate of Jose

Eugenio Ramirez is hereby ordered distributed as

follows:

One-half (1/2) thereof to his widow as her legitime;

One-half (1/2) thereof which is the free portion to

Roberto and Jorge Ramirez in naked ownership and

the usufruct to Wanda de Wrobleski with a simple

substitution in favor of Juan Pablo Jankowski and

Horace V. Ramirez.

The distribution herein ordered supersedes that of the

court a quo. No special pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-17587

September 12, 1967

PHILIPPINE BANKING CORPORATION,

representing the estate of JUSTINA SANTOS Y

CANON FAUSTINO, deceased, plaintiff-appellant,

vs.

LUI SHE in her own behalf and as administratrix of

the intestate estate of Wong Heng,

deceased,defendant-appellant.

Nicanor S. Sison for plaintiff-appellant.

Ozaeta, Gibbs & Ozaeta for defendant-appellant.

CASTRO, J.:

Justina Santos y Canon Faustino and her sister

Lorenzo were the owners in common of a piece of land

in Manila. This parcel, with an area of 2,582.30 square

meters, is located on Rizal Avenue and opens into

Florentino Torres street at the back and Katubusan

street on one side. In it are two residential houses with

entrance on Florentino Torres street and the Hen Wah

Restaurant with entrance on Rizal Avenue. The sisters

lived in one of the houses, while Wong Heng, a

Chinese, lived with his family in the restaurant. Wong

had been a long-time lessee of a portion of the

property, paying a monthly rental of P2,620.

On September 22, 1957 Justina Santos became the

owner of the entire property as her sister died with no

other heir. Then already well advanced in years, being

at the time 90 years old, blind, crippled and an invalid,

she was left with no other relative to live with. Her only

companions in the house were her 17 dogs and 8

maids. Her otherwise dreary existence was brightened

now and then by the visits of Wong's four children who

had become the joy of her life. Wong himself was the

trusted man to whom she delivered various amounts

for safekeeping, including rentals from her property at

the corner of Ongpin and Salazar streets and the

rentals which Wong himself paid as lessee of a part of

the Rizal Avenue property. Wong also took care of the

payment; in her behalf, of taxes, lawyers' fees, funeral

expenses, masses, salaries of maids and security

guard, and her household expenses.

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 4

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

"In grateful acknowledgment of the personal services

of the lessee to her," Justina Santos executed on

November 15, 1957 a contract of lease (Plff Exh. 3) in

favor of Wong, covering the portion then already

leased to him and another portion fronting Florentino

Torres street. The lease was for 50 years, although the

lessee was given the right to withdraw at any time from

the agreement; the monthly rental was P3,120. The

contract covered an area of 1,124 square meters. Ten

days later (November 25), the contract was amended

(Plff Exh. 4) so as to make it cover the entire property,

including the portion on which the house of Justina

Santos stood, at an additional monthly rental of P360.

For his part Wong undertook to pay, out of the rental

due from him, an amount not exceeding P1,000 a

month for the food of her dogs and the salaries of her

maids.

On December 21 she executed another contract (Plff

Exh. 7) giving Wong the option to buy the leased

premises for P120,000, payable within ten years at a

monthly installment of P1,000. The option, written in

Tagalog, imposed on him the obligation to pay for the

food of the dogs and the salaries of the maids in her

household, the charge not to exceed P1,800 a month.

The option was conditioned on his obtaining Philippine

citizenship, a petition for which was then pending in

the Court of First Instance of Rizal. It appears,

however, that this application for naturalization was

withdrawn when it was discovered that he was not a

resident of Rizal. On October 28, 1958 she filed a

petition to adopt him and his children on the erroneous

belief that adoption would confer on them Philippine

citizenship. The error was discovered and the

proceedings were abandoned.

On November 18, 1958 she executed two other

contracts, one (Plff Exh. 5) extending the term of the

lease to 99 years, and another (Plff Exh. 6) fixing the

term of the option of 50 years. Both contracts are

written in Tagalog.

In two wills executed on August 24 and 29, 1959 (Def

Exhs. 285 & 279), she bade her legatees to respect

the contracts she had entered into with Wong, but in a

codicil (Plff Exh. 17) of a later date (November 4,

1959) she appears to have a change of heart.

Claiming that the various contracts were made by her

because of machinations and inducements practiced

by him, she now directed her executor to secure the

annulment of the contracts.

On November 18 the present action was filed in the

Court of First Instance of Manila. The complaint

alleged that the contracts were obtained by Wong

"through fraud, misrepresentation, inequitable conduct,

undue influence and abuse of confidence and trust of

and (by) taking advantage of the helplessness of the

plaintiff and were made to circumvent the constitutional

provision prohibiting aliens from acquiring lands in the

Philippines and also of the Philippine Naturalization

Laws." The court was asked to direct the Register of

Deeds of Manila to cancel the registration of the

contracts and to order Wong to pay Justina Santos the

additional rent of P3,120 a month from November 15,

1957 on the allegation that the reasonable rental of the

leased premises was P6,240 a month.

In his answer, Wong admitted that he enjoyed her trust

and confidence as proof of which he volunteered the

information that, in addition to the sum of P3,000 which

he said she had delivered to him for safekeeping,

another sum of P22,000 had been deposited in a joint

account which he had with one of her maids. But he

denied having taken advantage of her trust in order to

secure the execution of the contracts in question. As

counterclaim he sought the recovery of P9,210.49

which he said she owed him for advances.

Wong's admission of the receipt of P22,000 and

P3,000 was the cue for the filing of an amended

complaint. Thus on June 9, 1960, aside from the nullity

of the contracts, the collection of various amounts

allegedly delivered on different occasions was sought.

These amounts and the dates of their delivery are

P33,724.27 (Nov. 4, 1957); P7,344.42 (Dec. 1, 1957);

P10,000 (Dec. 6, 1957); P22,000 and P3,000 (as

admitted in his answer). An accounting of the rentals

from the Ongpin and Rizal Avenue properties was also

demanded.

In the meantime as a result of a petition for

guardianship filed in the Juvenile and Domestic

Relations Court, the Security Bank & Trust Co. was

appointed guardian of the properties of Justina Santos,

while Ephraim G. Gochangco was appointed guardian

of her person.

In his answer, Wong insisted that the various contracts

were freely and voluntarily entered into by the parties.

He likewise disclaimed knowledge of the sum of

P33,724.27, admitted receipt of P7,344.42 and

P10,000, but contended that these amounts had been

spent in accordance with the instructions of Justina

Santos; he expressed readiness to comply with any

order that the court might make with respect to the

sums of P22,000 in the bank and P3,000 in his

possession.

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 5

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

The case was heard, after which the lower court

rendered judgment as follows:

[A]ll the documents mentioned in the first cause of

action, with the exception of the first which is the lease

contract of 15 November 1957, are declared null and

void; Wong Heng is condemned to pay unto plaintiff

thru guardian of her property the sum of P55,554.25

with legal interest from the date of the filing of the

amended complaint; he is also ordered to pay the sum

of P3,120.00 for every month of his occupation as

lessee under the document of lease herein sustained,

from 15 November 1959, and the moneys he has

consigned since then shall be imputed to that; costs

against Wong Heng.

From this judgment both parties appealed directly to

this Court. After the case was submitted for decision,

both parties died, Wong Heng on October 21, 1962

and Justina Santos on December 28, 1964. Wong was

substituted by his wife, Lui She, the other defendant in

this case, while Justina Santos was substituted by the

Philippine Banking Corporation.

Justina Santos maintained now reiterated by the

Philippine Banking Corporation that the lease

contract (Plff Exh. 3) should have been annulled along

with the four other contracts (Plff Exhs. 4-7) because it

lacks mutuality; because it included a portion which, at

the time, was in custodia legis; because the contract

was obtained in violation of the fiduciary relations of

the parties; because her consent was obtained through

undue influence, fraud and misrepresentation; and

because the lease contract, like the rest of the

contracts, is absolutely simulated.

Paragraph 5 of the lease contract states that "The

lessee may at any time withdraw from this agreement."

It is claimed that this stipulation offends article 1308 of

the Civil Code which provides that "the contract must

bind both contracting parties; its validity or compliance

cannot be left to the will of one of them."

We have had occasion to delineate the scope and

application of article 1308 in the early case of Taylor v.

Uy Tieng Piao.1 We said in that case:

Article 1256 [now art. 1308] of the Civil Code in our

opinion creates no impediment to the insertion in a

contract for personal service of a resolutory condition

permitting the cancellation of the contract by one of the

parties. Such a stipulation, as can be readily seen,

does not make either the validity or the fulfillment of

the contract dependent upon the will of the party to

whom is conceded the privilege of cancellation; for

where the contracting parties have agreed that such

option shall exist, the exercise of the option is as much

in the fulfillment of the contract as any other act which

may have been the subject of agreement. Indeed, the

cancellation of a contract in accordance with

conditions agreed upon beforehand is fulfillment.2

And so it was held in Melencio v. Dy Tiao Lay 3 that a

"provision in a lease contract that the lessee, at any

time before he erected any building on the land, might

rescind the lease, can hardly be regarded as a

violation of article 1256 [now art. 1308] of the Civil

Code."

The

case

of Singson

Encarnacion

v.

Baldomar 4 cannot be cited in support of the claim of

want of mutuality, because of a difference in factual

setting. In that case, the lessees argued that they

could occupy the premises as long as they paid the

rent. This is of course untenable, for as this Court said,

"If this defense were to be allowed, so long as

defendants elected to continue the lease by continuing

the payment of the rentals, the owner would never be

able to discontinue it; conversely, although the owner

should desire the lease to continue the lessees could

effectively thwart his purpose if they should prefer to

terminate the contract by the simple expedient of

stopping payment of the rentals." Here, in contrast, the

right of the lessee to continue the lease or to terminate

it is so circumscribed by the term of the contract that it

cannot be said that the continuance of the lease

depends upon his will. At any rate, even if no term had

been fixed in the agreement, this case would at most

justify the fixing of a period 5 but not the annulment of

the contract.

Nor is there merit in the claim that as the portion of the

property formerly owned by the sister of Justina

Santos was still in the process of settlement in the

probate court at the time it was leased, the lease is

invalid as to such portion. Justina Santos became the

owner of the entire property upon the death of her

sister Lorenzo on September 22, 1957 by force of

article 777 of the Civil Code. Hence, when she leased

the property on November 15, she did so already as

owner thereof. As this Court explained in upholding the

sale made by an heir of a property under judicial

administration:

That the land could not ordinarily be levied upon while

in custodia legis does not mean that one of the heirs

may not sell the right, interest or participation which he

has or might have in the lands under administration.

The ordinary execution of property in custodia legis is

prohibited in order to avoid interference with the

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 6

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

possession by the court. But the sale made by an heir

of his share in an inheritance, subject to the result of

the pending administration, in no wise stands in the

way of such administration.6

It is next contended that the lease contract was

obtained by Wong in violation of his fiduciary

relationship with Justina Santos, contrary to article

1646, in relation to article 1941 of the Civil Code,

which disqualifies "agents (from leasing) the property

whose administration or sale may have been entrusted

to them." But Wong was never an agent of Justina

Santos. The relationship of the parties, although

admittedly close and confidential, did not amount to an

agency so as to bring the case within the prohibition of

the law.

Just the same, it is argued that Wong so completely

dominated her life and affairs that the contracts

express not her will but only his. Counsel for Justina

Santos cites the testimony of Atty. Tomas S. Yumol

who said that he prepared the lease contract on the

basis of data given to him by Wong and that she told

him that "whatever Mr. Wong wants must be

followed."7

The testimony of Atty. Yumol cannot be read out of

context in order to warrant a finding that Wong

practically dictated the terms of the contract. What this

witness said was:

Q Did you explain carefully to your client, Doa

Justina, the contents of this document before she

signed it?

A I explained to her each and every one of these

conditions and I also told her these conditions were

quite onerous for her, I don't really know if I have

expressed my opinion, but I told her that we would

rather not execute any contract anymore, but to hold it

as it was before, on a verbal month to month contract

of lease.

xxx

xxx

xxx

Q So, as far as consent is concerned, you were

satisfied that this document was perfectly proper?

xxx

xxx

xxx

A Your Honor, if I have to express my personal opinion,

I would say she is not, because, as I said before, she

told me "Whatever Mr. Wong wants must be

followed."8

Wong might indeed have supplied the data which Atty.

Yumol embodied in the lease contract, but to say this

is not to detract from the binding force of the contract.

For the contract was fully explained to Justina Santos

by her own lawyer. One incident, related by the same

witness, makes clear that she voluntarily consented to

the lease contract. This witness said that the original

term fixed for the lease was 99 years but that as he

doubted the validity of a lease to an alien for that

length of time, he tried to persuade her to enter instead

into a lease on a month-to-month basis. She was,

however, firm and unyielding. Instead of heeding the

advice of the lawyer, she ordered him, "Just follow Mr.

Wong Heng."9 Recounting the incident, Atty. Yumol

declared on cross examination:

Considering her age, ninety (90) years old at the time

and her condition, she is a wealthy woman, it is just

natural when she said "This is what I want and this will

be done." In particular reference to this contract of

lease, when I said "This is not proper," she said

"You just go ahead, you prepare that, I am the owner,

and if there is any illegality, I am the only one that can

question the illegality."10

Q Agreed what?

Atty. Yumol further testified that she signed the lease

contract in the presence of her close friend,

Hermenegilda Lao, and her maid, Natividad Luna, who

was constantly by her side.11 Any of them could have

testified on the undue influence that Wong supposedly

wielded over Justina Santos, but neither of them was

presented as a witness. The truth is that even after

giving his client time to think the matter over, the

lawyer could not make her change her mind. This

persuaded the lower court to uphold the validity of the

lease contract against the claim that it was procured

through undue influence.

A Agreed with my objectives that it is really onerous

and that I was really right, but after that, I was called

again by her and she told me to follow the wishes of

Mr. Wong Heng.

Indeed, the charge of undue influence in this case

rests on a mere inference 12 drawn from the fact that

Justina Santos could not read (as she was blind) and

did not understand the English language in which the

Q But, she did not follow your advice, and she went

with the contract just the same?

A She agreed first . . .

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 7

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

contract is written, but that inference has been

overcome by her own evidence.

Nor is there merit in the claim that her consent to the

lease contract, as well as to the rest of the contracts in

question, was given out of a mistaken sense of

gratitude to Wong who, she was made to believe, had

saved her and her sister from a fire that destroyed their

house during the liberation of Manila. For while a

witness claimed that the sisters were saved by other

persons (the brothers Edilberto and Mariano Sta.

Ana)13 it was Justina Santos herself who, according to

her own witness, Benjamin C. Alonzo, said "very

emphatically" that she and her sister would have

perished in the fire had it not been for Wong. 14 Hence

the recital in the deed of conditional option (Plff Exh. 7)

that "[I]tong si Wong Heng ang siyang nagligtas sa

aming dalawang magkapatid sa halos ay tiyak na

kamatayan", and the equally emphatic avowal of

gratitude in the lease contract (Plff Exh. 3).

As it was with the lease contract (Plff Exh. 3), so it was

with the rest of the contracts (Plff Exhs. 4-7) the

consent of Justina Santos was given freely and

voluntarily. As Atty. Alonzo, testifying for her, said:

[I]n nearly all documents, it was either Mr. Wong Heng

or Judge Torres and/or both. When we had

conferences, they used to tell me what the documents

should contain. But, as I said, I would always ask the

old woman about them and invariably the old woman

used to tell me: "That's okay. It's all right."15

But the lower court set aside all the contracts, with the

exception of the lease contract of November 15, 1957,

on the ground that they are contrary to the expressed

wish of Justina Santos and that their considerations

are fictitious. Wong stated in his deposition that he did

not pay P360 a month for the additional premises

leased to him, because she did not want him to, but

the trial court did not believe him. Neither did it believe

his statement that he paid P1,000 as consideration for

each of the contracts (namely, the option to buy the

leased premises, the extension of the lease to 99

years, and the fixing of the term of the option at 50

years), but that the amount was returned to him by her

for safekeeping. Instead, the court relied on the

testimony of Atty. Alonzo in reaching the conclusion

that the contracts are void for want of consideration.

Atty. Alonzo declared that he saw no money paid at the

time of the execution of the documents, but his

negative testimony does not rule out the possibility that

the considerations were paid at some other time as the

contracts in fact recite. What is more, the consideration

need not pass from one party to the other at the time a

contract is executed because the promise of one is the

consideration for the other.16

With respect to the lower court's finding that in all

probability Justina Santos could not have intended to

part with her property while she was alive nor even to

lease it in its entirety as her house was built on it,

suffice it to quote the testimony of her own witness and

lawyer who prepared the contracts (Plff Exhs. 4-7) in

question, Atty. Alonzo:

The ambition of the old woman, before her death,

according to her revelation to me, was to see to it that

these properties be enjoyed, even to own them, by

Wong Heng because Doa Justina told me that she

did not have any relatives, near or far, and she

considered Wong Heng as a son and his children her

grandchildren; especially her consolation in life was

when she would hear the children reciting prayers in

Tagalog.17

She was very emphatic in the care of the seventeen

(17) dogs and of the maids who helped her much, and

she told me to see to it that no one could disturb Wong

Heng from those properties. That is why we thought of

the ninety-nine (99) years lease; we thought of

adoption, believing that thru adoption Wong Heng

might acquire Filipino citizenship; being the adopted

child of a Filipino citizen.18

This is not to say, however, that the contracts (Plff

Exhs. 3-7) are valid. For the testimony just quoted,

while dispelling doubt as to the intention of Justina

Santos, at the same time gives the clue to what we

view as a scheme to circumvent the Constitutional

prohibition against the transfer of lands to aliens. "The

illicit

purpose

then

becomes

the

19

illegal causa" rendering the contracts void.

Taken singly, the contracts show nothing that is

necessarily illegal, but considered collectively, they

reveal an insidious pattern to subvert by indirection

what the Constitution directly prohibits. To be sure, a

lease to an alien for a reasonable period is valid. So is

an option giving an alien the right to buy real property

on condition that he is granted Philippine citizenship.

As this Court said in Krivenko v. Register of Deeds:20

[A]liens are not completely excluded by the

Constitution from the use of lands for residential

purposes. Since their residence in the Philippines is

temporary, they may be granted temporary rights such

as a lease contract which is not forbidden by the

Constitution. Should they desire to remain here forever

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 8

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

and share our fortunes and misfortunes, Filipino

citizenship is not impossible to acquire.

But if an alien is given not only a lease of, but also an

option to buy, a piece of land, by virtue of which the

Filipino owner cannot sell or otherwise dispose of his

property,21 this to last for 50 years, then it becomes

clear that the arrangement is a virtual transfer of

ownership whereby the owner divests himself in

stages not only of the right to enjoy the land ( jus

possidendi, jus utendi, jus fruendi and jus abutendi)

but also of the right to dispose of it ( jus disponendi)

rights the sum total of which make up ownership. It is

just as if today the possession is transferred,

tomorrow, the use, the next day, the disposition, and

so on, until ultimately all the rights of which ownership

is made up are consolidated in an alien. And yet this is

just exactly what the parties in this case did within the

space of one year, with the result that Justina Santos'

ownership of her property was reduced to a hollow

concept. If this can be done, then the Constitutional

ban against alien landholding in the Philippines, as

announced in Krivenko v. Register of Deeds,22 is

indeed in grave peril.

It does not follow from what has been said, however,

that because the parties are in pari delicto they will be

left where they are, without relief. For one thing, the

original parties who were guilty of a violation of the

fundamental charter have died and have since been

substituted by their administrators to whom it would be

unjust to impute their guilt.23 For another thing, and this

is not only cogent but also important, article 1416 of

the Civil Code provides, as an exception to the rule

on pari delicto, that "When the agreement is not

illegal per se but is merely prohibited, and the

prohibition by law is designed for the protection of the

plaintiff, he may, if public policy is thereby enhanced,

recover what he has paid or delivered." The

Constitutional provision that "Save in cases of

hereditary succession, no private agricultural land shall

be transferred or assigned except to individuals,

corporations, or associations qualified to acquire or

hold lands of the public domain in the Philippines" 24 is

an expression of public policy to conserve lands for the

Filipinos. As this Court said in Krivenko:

It is well to note at this juncture that in the present case

we have no choice. We are construing the Constitution

as it is and not as we may desire it to be. Perhaps the

effect of our construction is to preclude aliens admitted

freely into the Philippines from owning sites where they

may build their homes. But if this is the solemn

mandate of the Constitution, we will not attempt to

compromise it even in the name of amity or equity . . . .

For all the foregoing, we hold that under the

Constitution aliens may not acquire private or public

agricultural lands, including residential lands, and,

accordingly, judgment is affirmed, without costs.25

That policy would be defeated and its continued

violation sanctioned if, instead of setting the contracts

aside and ordering the restoration of the land to the

estate of the deceased Justina Santos, this Court

should apply the general rule of pari delicto. To the

extent that our ruling in this case conflicts with that laid

down in Rellosa v. Gaw Chee Hun 26 and subsequent

similar cases, the latter must be considered as pro

tanto qualified.

The claim for increased rentals and attorney's fees,

made in behalf of Justina Santos, must be denied for

lack of merit.

And what of the various amounts which Wong received

in trust from her? It appears that he kept two classes of

accounts, one pertaining to amount which she

entrusted to him from time to time, and another

pertaining to rentals from the Ongpin property and

from the Rizal Avenue property, which he himself was

leasing.

With respect to the first account, the evidence shows

that he received P33,724.27 on November 8, 1957

(Plff Exh. 16); P7,354.42 on December 1, 1957 (Plff

Exh. 13); P10,000 on December 6, 1957 (Plff Exh.

14) ; and P18,928.50 on August 26, 1959 (Def. Exh.

246), or a total of P70,007.19. He claims, however,

that he settled his accounts and that the last amount of

P18,928.50 was in fact payment to him of what in the

liquidation was found to be due to him.

He made disbursements from this account to

discharge Justina Santos' obligations for taxes,

attorneys' fees, funeral services and security guard

services, but the checks (Def Exhs. 247-278) drawn by

him

for

this

purpose

amount

to

only

P38,442.84.27 Besides, if he had really settled his

accounts with her on August 26, 1959, we cannot

understand why he still had P22,000 in the bank and

P3,000 in his possession, or a total of P25,000. In his

answer, he offered to pay this amount if the court so

directed him. On these two grounds, therefore, his

claim of liquidation and settlement of accounts must be

rejected.

After subtracting P38,442.84 (expenditures) from

P70,007.19 (receipts), there is a difference of P31,564

which, added to the amount of P25,000, leaves a

balance of P56,564.3528 in favor of Justina Santos.

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 9

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

As to the second account, the evidence shows that the

monthly income from the Ongpin property until its sale

in Rizal Avenue July, 1959 was P1,000, and that from

the Rizal Avenue property, of which Wong was the

lessee, was P3,120. Against this account the

household expenses and disbursements for the care of

the 17 dogs and the salaries of the 8 maids of Justina

Santos were charged. This account is contained in a

notebook (Def. Exh. 6) which shows a balance of

P9,210.49 in favor of Wong. But it is claimed that the

rental from both the Ongpin and Rizal Avenue

properties was more than enough to pay for her

monthly expenses and that, as a matter of fact, there

should be a balance in her favor. The lower court did

not allow either party to recover against the other. Said

the court:

[T]he documents bear the earmarks of genuineness;

the trouble is that they were made only by Francisco

Wong and Antonia Matias, nick-named Toning,

which was the way she signed the loose sheets, and

there is no clear proof that Doa Justina had

authorized these two to act for her in such liquidation;

on the contrary if the result of that was a deficit as

alleged and sought to be there shown, of P9,210.49,

that was not what Doa Justina apparently understood

for as the Court understands her statement to the

Honorable Judge of the Juvenile Court . . . the reason

why she preferred to stay in her home was because

there she did not incur in any debts . . . this being the

case, . . . the Court will not adjudicate in favor of Wong

Heng on his counterclaim; on the other hand, while it is

claimed that the expenses were much less than the

rentals and there in fact should be a superavit, . . . this

Court must concede that daily expenses are not easy

to compute, for this reason, the Court faced with the

choice of the two alternatives will choose the middle

course which after all is permitted by the rules of proof,

Sec. 69, Rule 123 for in the ordinary course of things,

a person will live within his income so that the

conclusion of the Court will be that there is neither

deficit nor superavit and will let the matter rest here.

Both parties on appeal reiterate their respective claims

but we agree with the lower court that both claims

should be denied. Aside from the reasons given by the

court, we think that the claim of Justina Santos totalling

P37,235, as rentals due to her after deducting various

expenses, should be rejected as the evidence is none

too clear about the amounts spent by Wong for

food29 masses30 and salaries of her maids. 31 His claim

for P9,210.49 must likewise be rejected as his

averment of liquidation is belied by his own admission

that even as late as 1960 he still had P22,000 in the

bank and P3,000 in his possession.

ACCORDINGLY, the contracts in question (Plff Exhs.

3-7) are annulled and set aside; the land subjectmatter of the contracts is ordered returned to the

estate of Justina Santos as represented by the

Philippine Banking Corporation; Wong Heng (as

substituted by the defendant-appellant Lui She) is

ordered to pay the Philippine Banking Corporation the

sum of P56,564.35, with legal interest from the date of

the filing of the amended complaint; and the amounts

consigned in court by Wong Heng shall be applied to

the payment of rental from November 15, 1959 until

the premises shall have been vacated by his heirs.

Costs against the defendant-appellant.

REPUBLIC v. QUASHA

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. L-30299

August 17, 1972

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES and/or THE

SOLICITOR GENERAL petitioners,

vs.

WILLIAM H. QUASHA, respondent.

Office of the Solicitor General Estelito P. Mendoza for

petitioner.

Quasha, Asperilla Blanco, Zafra & Tayag for

respondent.

REYES J. B. L., J.:p

This case involves a judicial determination of the

scope and duration of the rights acquired by American

citizens and corporations controlled by them, under the

Ordinance appended to the Constitution as of 18

September 1946, or the so-called Parity Amendment.

The respondent, William H. Quasha, an American

citizen, had acquired by purchase on 26 November

1954 a parcel of land with the permanent

improvements thereon, situated at 22 Molave Place, in

Forbes Park, Municipality of Makati, Province of Rizal,

with an area of 2,616 sq. m. more or less, described in

and covered by T. C. T. 36862. On 19 March 1968, he

filed a petition in the Court of First Instance of Rizal,

docketed as its Civil Case No. 10732, wherein he

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 10

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

(Quasha) averred the acquisition of the real estate

aforesaid; that the Republic of the Philippines, through

its officials, claimed that upon expiration of the Parity

Amendment on 3 July 1974, rights acquired by citizens

of the United States of America shall cease and be of

no further force and effect; that such claims

necessarily affect the rights and interest of the plaintiff,

and that continued uncertainty as to the status of

plaintiff's property after 3 July 1974 reduces the value

thereof, and precludes further improvements being

introduced thereon, for which reason plaintiff Quasha

sought a declaration of his rights under the Parity

Amendment, said plaintiff contending that the

ownership of properties during the effectivity of the

Parity Amendment continues notwithstanding the

termination and effectivity of the Amendment.

The then Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo (and

later on his successors in office, Felix V. Makasiar and

Felix Q. Antonio) contended that the land acquired by

plaintiff constituted private agricultural land and that

the acquisition violated section 5, Article XIII, of the

Constitution of the Philippines, which prohibits the

transfer of private agricultural land to non-Filipinos,

except by hereditary succession; and assuming,

without conceding, that Quasha's acquisition was valid,

any and all rights by him so acquired "will expire ipso

facto and ipso jure at the end of the day on 3 July

1974, if he continued to hold the property until then,

and will be subject to escheat or reversion

proceedings" by the Republic.

After hearing, the Court of First Instance of Rizal

(Judge Pedro A. Revilla presiding) rendered a

decision, dated 6 March 1969, in favor of plaintiff, with

the following dispositive portion:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered declaring

that acquisition by the plaintiff on 26 November 1954

of, the private agricultural land described in and

covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 36862 in his

name was valid, and that plaintiff has a right to

continue in ownership of the said property even

beyond July 3, 1974.

Defendants appealed directly to this Court on

questions of law, pleading that the court below erred:

(1) In ruling that under the Parity Amendment

American citizens and American owned and/or

controlled business enterprises "are also qualified to

acquire private agricultural lands" in the Philippines;

and

(2) In ruling that when the Parity Amendment ceases to

be effective on 3 July 1974, "what must be considered

to end should be the right to acquire land, and not the

right to continue in ownership of land already acquired

prior to that time."

As a historical background, requisite to a proper

understanding of the issues being litigated, it should be

recalled that the Constitution as originally adopted,

contained the following provisions:

Article XIII CONSERVATION AND UTILIZATION

OF NATURAL RESOURCES

Section 1. All Agricultural, timber, and mineral lands of

the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum,

and other mineral oils, all forces of potential energy,

and other natural resources of the Philippines belong

to the State, and their disposition, exploitation,

development, or utilization shall be limited to citizens of

the Philippines, or to corporations or associations at

least sixty per centum of the capital of which is owned

by such citizens subject to any existing right, grant,

lease, or concession at the time of the inauguration of

the Government established under this Constitution.

Natural resources, with the exception of public

agricultural land, shall not be alienated, and no license,

concession, or lease for the resources shall be granted

for a period exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for

another twenty-five years, except as to water right for

irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses

other than the development of water power, in which

cases beneficial use may be the measure and the limit

of the grant.

Section 2. No private corporation or association may

acquire, lease, or hold public agricultural lands in

excess of one thousand and twenty-four hectares, nor

may any individual acquire such lands by purchase in

excess of one hundred and forty-four hectares, or by

lease in excess of one thousand and twenty-four

hectares, or by homestead in excess of twenty-four

hectares. Lands adapted to grazing not exceeding two

thousand hectares, may be leased to an individual,

private corporation, or association.

xxx

xxx

xxx

Section 5. Save in cases of hereditary succession, no

private agricultural land shall be transferred or

assigned except to individuals, corporations, or

associations qualified to acquire or hold lands of the

public domain in the Philippines.

Article XIV GENERAL PROVISIONS

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 11

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

Section 8. No franchise, certificate, or any other form

of authorization for the operation of a public utility shall

be granted except to citizens of the Philippines or to

corporations or other entities organized under the laws

of the Philippines, sixty per centum of the capital of

which is owned by citizens of the Philippines, nor shall

such franchise, certificate, or authorization be

exclusive in character or for a longer period than fifty

years. No franchise or right shall be granted to any

individual, firm, or corporation, except under the

condition that it shall be subject to amendment,

alteration, or repeal by the Congress when the public

interest so requires.

The nationalistic spirit that pervaded these and other

provisions of the Constitution are self-evident and

require no further emphasis.

From the Japanese occupation and the reconquest of

the Archipelago, the Philippine nation emerged with its

industries destroyed and its economy dislocated. It

was described in this Court's opinion in Commissioner

of Internal Revenue vs. Guerrero, et al.,

L-20942, 22 September 1967, 21 SCRA 181, 187,

penned by Justice Enrique M. Fernando, in the

following terms:

It was fortunate that the Japanese Occupation ended

when it did. Liberation was hailed by all, but the

problems faced by the legitimate government were

awesome in their immensity. The Philippine treasury

was bankrupt and her economy prostrate. There were

no dollar-earning export crops to speak of; commercial

operations were paralyzed; and her industries were

unable to produce with mills, factories and plants either

destroyed or their machineries obsolete or dismantled.

It was a desolate and tragic sight that greeted the

victorious American and Filipino troops. Manila,

particularly that portion south of the Pasig, lay in ruins,

its public edifices and business buildings lying in a

heap of rubble and numberless houses razed to the

ground. It was in fact, next to Warsaw, the most

devastated city in the expert opinion of the then

General Eisenhower. There was thus a clear need of

help from the United States. American aid was

forthcoming but on terms proposed by her government

and later on accepted by the Philippines.

The foregoing description is confirmed by the 1945

Report of the Committee on Territories and Insular

Affairs to the United States Congress:

When the Philippines do become independent next

July, they will start on the road to independence with a

country whose commerce, trade and political

institutions have been very, very seriously damaged.

Years of rebuilding are necessary before the former

physical conditions of the islands can be restored.

Factories, homes, government and commercial

buildings, roads, bridges, docks, harbors and the like

are in need of complete reconstruction or widespread

repairs. It will be quite some while before the Philippine

can produce sufficient food with which to sustain

themselves.

The internal revenues of the country have been greatly

diminished by war. Much of the assessable property

basis has been destroyed. Foreign trade has vanished.

Internal commerce is but a faction of what it used to

be. Machinery, farming implements, ships, bus and

truck

lines,

inter-island

transportation

and

communications have been wrecked.

Shortly thereafter, in 1946, the United States 79th

Congress enacted Public Law 3721, known as the

Philippine Trade Act, authorizing the President of the

United States to enter into an Executive Agreement

with the President of the Philippines, which should

contain a provision that

The disposition, exploitation, development, and

utilization of all agricultural, timber, and mineral lands

of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal,

petroleum, and other mineral oils,; all forces and

sources of potential energy, and other natural

resources of the Philippines, and the operation of

public utilities shall, if open to any person, be open to

citizens of the United States and to all forms of

business enterprise owned or controlled, directly or

indirectly, by United States citizens.

and that:

The President of the United States is not authorized ...

to enter into such executive agreement unless in the

agreement the Government of the Philippines ... will

promptly take such steps as are necessary to secure

the amendment of the Constitution of the Philippines

so as to permit the taking effect as laws of the

Philippines of such part of the provisions of section

1331 ... as is in conflict with such Constitution before

such amendment.

The Philippine Congress, by Commonwealth Act No.

733, authorized the President of the Philippines to

enter into the Executive Agreement. Said Act

provided, inter alia, the following:

ARTICLE VII

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 12

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

1. The disposition, exploitation, development, and

utilization of all agricultural, timber, and mineral lands

of the public domain, waters, mineral, coal, petroleum,

and other mineral oils, all forces and sources of

potential energy, and other natural resources of the

Philippines, and the operation of public utilities, shall, if

open to any person, be open to citizens of the United

States and to all forms of business enterprise owned

or controlled, directly or indirectly, by United States

citizens, except that (for the period prior to the

amendment of the Constitution of the Philippines

referred to in Paragraph 2 of this Article) the

Philippines shall not be required to comply with such

part of the foregoing provisions of this sentence as are

in conflict with such Constitution.

2. The Government of the Philippines will promptly

take such steps as are necessary to secure the

amendment of the constitution of the Philippines so as

to permit the taking effect as laws of the Philippines of

such part of the provisions of Paragraph 1 of this

Article as is in conflict with such Constitution before

such amendment.

Thus authorized, the Executive Agreement was signed

on 4 July 1946, and shortly thereafter the President of

the Philippines recommended to the Philippine

Congress the approval of a resolution proposing

amendments to the Philippine Constitution pursuant to

the Executive Agreement. Approved by the Congress

in joint session, the proposed amendment was

submitted to a plebiscite and was ratified in November

of 1946. Generally known as the Parity Amendment, it

was in the form of an Ordinance appended to the

Philippine Constitution, reading as follows:

Notwithstanding the provision of section one, Article

Thirteen, and section eight, Article Fourteen, of the

foregoing Constitution, during the effectivity of the

Executive Agreement entered into by the President of

the Philippines with the President of the United States

on the fourth of July, nineteen hundred and forty-six,

pursuant to the provisions of Commonwealth Act

Numbered Seven hundred and thirty-three, but in no

case to extend beyond the third of July, nineteen

hundred and seventy-four, the disposition, exploitation,

development, and utilization of all agricultural, timber,

and mineral lands of the public domain, waters,

minerals, coals, petroleum, and other mineral oils, all

forces and sources of potential energy, and other

natural resources of the Philippines, and the operation

of public utilities, shall, if OPEN to any person, be open

to citizens of the United States and to all forms of

business enterprise owned or controlled, directly or

indirectly, by citizens of the United States in the same

manner as to and under the same conditions imposed

upon, citizens of the Philippines or corporations or

associations owned or controlled by citizens of the

Philippines.

A revision of the 1946 Executive Agreement was

authorized by the Philippines by Republic Act 1355,

enacted in July 1955. The revision was duly negotiated

by representatives of the Philippines and the United

States, and a new agreement was concluded on 6

September 1955 to take effect on 1 January 1956,

becoming known as the Laurel-Langley Agreement.

This latter agreement, however, has no direct

application to the case at bar, since the purchase by

herein respondent Quasha of the property in question

was made in 1954, more than one year prior to the

effectivity of the Laurel-Langley Agreement..

I

Bearing in mind the legal provisions previously quoted

and their background, We turn to the first main issue

posed in this appeal: whether under or by virtue of the

so-called Parity Amendment to the Philippine

Constitution respondent Quasha could validly acquire

ownership of the private residential land in Forbes

Park, Makati, Rizal, which is concededly classified

private agricultural land.

Examination of the "Parity Amendment", as ratified,

reveals that it only establishes an express exception to

two (2) provisions of our Constitution, to wit: (a)

Section 1, Article XIII, re disposition, exploitation,

development and utilization of agricultural, timber and

mineral lands of the public domain and other natural

resources of the Philippines; and (b) Section 8, Article

XIV, regarding operation of public utilities. As originally

drafted by the framers of the Constitution, the privilege

to acquire and exploit agricultural lands of the public

domain, and other natural resources of the Philippines,

and to operate public utilities, were reserved to

Filipinos and entities owned or controlled by them: but

the "Parity Amendment" expressly extended the

privilege to citizens of the United States of America

and/or to business enterprises owned or controlled by

them.

No other provision of our Constitution was referred to

by the "Parity Amendment"; nor Section 2 of Article XIII

limiting the maximum area of public agricultural lands

that could be held by individuals or corporations or

associations; nor Section 5 restricting the transfer or

assignment of private agricultural lands to those

qualified to acquire or hold lands of the public domain

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 13

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

(which under the original Section 1 of Article XIII meant

Filipinos exclusively), save in cases of hereditary

succession. These sections 2 and 5 were therefore left

untouched and allowed to continue in operation as

originally intended by the Constitution's framers.

Respondent Quasha argues that since the amendment

permitted United States citizens or entities controlled

by them to acquire agricultural lands of the public

domain, then such citizens or entities became entitled

to acquire private agricultural land in the Philippines,

even without hereditary succession, since said section

5 of Article XIII only negates the transfer or assignment

of private agricultural land to individuals or entities not

qualified to acquire or hold lands of the public domain.

Clearly, this argument of respondent Quasha rests not

upon the text of the Constitutional Amendment but

upon a mere inference therefrom. If it was ever

intended to create also an exception to section 5 of

Article XIII, why was mention therein made only of

Section 1 of Article XIII and Section 8 of Article XIV

and of no other? When the text of the Amendment was

submitted for popular ratification, did the voters

understand that three sections of the Constitution were

to be modified, when only two sections were therein

mentioned?

A reading of Sections 1 and 4 of Article XIII, as

originally drafted by its farmers, leaves no doubt that

the policy of the Constitution was to reserve to

Filipinos the disposition, exploitation development or

utilization of agricultural lands, public (section 1) or

private (section 5), as well as all other natural

resources of the Philippines. The "Parity Amendment"

created exceptions to that Constitutional Policy and in

consequence to the sovereignty of the Philippines. By

all canons of construction, such exceptions must be

given strict interpretation; and this Court has already

so ruled in Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs.

Guerrero, et al., L-20942, 22 September 1967, 21

SCRA 181, per Justice Enrique M. Fernando:

While good faith, no less than adherence to the

categorical wording of the Ordinance, requires that all

the rights and privileges thus granted to Americans

and business enterprises owned and controlled by

them be respected, anything further would not be

warranted. Nothing less would suffice but anything

more is not justified.

The basis for the strict interpretation was given by

former President of the University of the Philippines,

Hon. Vicente G. Sinco (Congressional Record, House

of Representatives, Volume 1, No. 26, page 561):

It should be emphatically stated that the provisions of

our Constitution which limit to Filipinos the rights to

develop the natural resources and to operate the

public utilities of the Philippines is one of the bulwarks

of our national integrity. The Filipino people decided to

include it in our Constitution in order that it may have

the stability and permanency that its importance

requires. It is written in our Constitution so that it may

neither be the subject of barter nor be impaired in the

give and take of politics. With our natural resources,

our sources of power and energy, our public lands, and

our public utilities, the material basis of the nation's

existence, in the hands of aliens over whom the

Philippine Government does not have complete

control, the Filipinos may soon find themselves

deprived of their patrimony and living as it were, in a

house that no longer belongs to them.

The true extent of the Parity Amendment, as

understood by its proponents in the Philippine

Congress, was clearly expressed by one of its

advocates, Senator Lorenzo Sumulong:

It is a misconception to believe that under this

amendment Americans will be able to acquire all kinds

of natural resources of this country, and even after the

expiration of 28 years their acquired rights cannot be

divested from them. If we read carefully the language

of this amendment which is taken verbatim from the

Provision of the Bell Act, and, which in turn, is taken

also verbatim from certain sections of the Constitution,

you will find out that the equality of rights granted

under this amendment refers only to two subjects.

Firstly, it refers to exploitation of natural resources, and

secondly, it refers to the operation of public utilities.

Now, when it comes to exploitation of natural

resources, it must be pointed out here that, under our

Constitution and under this amendment, only public

agricultural land may be acquired, may be bought, so

that on the supposition that we give way to this

amendment and on the further supposition that it is

approved by our people, let not the mistaken belief be

entertained that all kinds of natural resources may be

acquired by Americans because under our Constitution

forest lands cannot be bought, mineral lands cannot be

bought, because by explicit provision of the

Constitution they belong to the State, they belong to

our Government, they belong to our people. That is

why we call them rightly the patrimony of our race.

Even if the Americans should so desire, they can have

no further privilege than to ask for a lease of

concession of forest lands and mineral lands because

it is so commanded in the Constitution. And under the

Constitution, such a concession is given only for a

limited period. It can be extended only for 25 years,

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 14

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

renewable for another 25. So that with respect to

mineral or forest lands, all they can do is to lease it for

25 years, and after the expiration of the original 25

years they will have to extend it, and I believe it can be

extended provided that it does not exceed 28 years

because this agreement is to be effected only as an

ordinance and for the express period of 28 years. So

that it is my humble belief that there is nothing to worry

about insofar as our forest and mineral lands are

concerned.

Now, coming to the operation of public utilities, as

every member of the Congress knows, it is also for a

limited period, under our Constitution, for a period not

exceeding 50 years. And since this amendment is

intended to endure only for 28 years, it is my humble

opinion that when Americans try to operate public

utilities they cannot take advantage of the maximum

provided in the Constitution but only the 28 years

which is expressly provided to be the life of this

amendment.

There remains for us to consider the case of our public

agricultural lands. To be sure, they may be bought, and

if we pass this amendment, Americans may buy our

public agricultural lands, but the very same

Constitution applying even to Filipinos, provides that

the sale of public agricultural lands to a corporation

can never exceed one thousand and twenty-four

hectares. That is to say, if an American corporation,

and American enterprise, should decide to invest its

money in public agricultural lands, it will be limited to

the amount of 1,024 hectares, no more than 1,024

hectares' (Emphasis supplied).

No views contrary to these were ever expressed in the

Philippine Legislature during the discussion of the

Proposed Amendment to our Constitution, nor was any

reference made to acquisition of private agricultural

lands by non-Filipinos except by hereditary

succession. On the American side, it is significant to

observe that the draft of the Philippine Trade Act

submitted to the House of Representatives by

Congressman Bell, provided in the first Portion of

Section 19 the following:

SEC. 19. Notwithstanding any existing provision of the

constitution and statutes of the Philippine Government,

citizens and corporations of the United States shall

enjoy in the Philippine Islands during the period of the

validity of this Act, or any extension thereof by statute

or treaty, the same rights as to property, residence,

and occupation as citizens of the Philippine Islands ...

But as finally approved by the United States Congress,

the equality as to " property residence and occupation"

provided in the bill was eliminated and Section 341 of

the Trade Act limited such parity to the disposition,

exploitation, development, and utilization of lands of

the public domain, and other natural resources of the

Philippines (V. ante, page 5 of this opinion).

Thus, whether from the Philippine or the American

side, the intention was to secure parity for United

States citizens, only in two matters: (1) exploitation,

development and utilization of public lands, and other

natural resources of the Philippines; and (2) the

operation of public utilities. That and nothing else.

Respondent Quasha avers that as of 1935 when the

Constitution was adopted, citizens of the United States

were already qualified to acquire public agricultural

lands, so that the literal text of section 5 must be

understood as permitting transfer or assignment of

private agricultural lands to Americans even without

hereditary succession. Such capacity of United States

citizens could exist only during the American

sovereignty over the Islands. For the Constitution of

the Philippines was designed to operate even beyond

the extinction of the United States sovereignty, when

the Philippines would become fully independent. That

is apparent from the provision of the original Ordinance

appended to the Constitution as originally approved

and ratified. Section 17 of said Ordinance provided

that:

(17) Citizens and corporations of the United States

shall enjoy in the Commonwealth of the Philippines all

the civil rights of the citizens and corporations,

respectively, thereof. (Emphasis supplied)

The import of paragraph (17) of the Ordinance was

confirmed and reenforced by Section 127 of

Commonwealth Act 141 (the Public Land Act of 1936)

that prescribes:

Sec. 127. During the existence and continuance of the

Commonwealth, and before the Republic of the

Philippines is established, citizens and corporations of

the United States shall enjoy the same rights granted

to citizens and corporations of the Philippines under

this Act.

thus clearly evidencing once more that equal rights of

citizens and corporations of the United States to

acquire agricultural lands of the Philippines vanished

with the advent of the Philippine Republic. Which

explains the need of introducing the "Parity

Amendment" of 1946.

LAND TITLES and DEEDS (Atty. Jeffrey Jefferson Coronel) 15

PRELIM EXAM COVERAGE - CASES

It is then indubitable that the right of United States

citizens and corporations to acquire and exploit private

or public lands and other natural resources of the

Philippines was intended to expire when the

Commonwealth ended on 4 July 1946. Thereafter,

public and private agricultural lands and natural

resources of the Philippines were or became

exclusively reserved by our Constitution for Filipino

citizens. This situation lasted until the "Parity

Amendment", ratified in November, 1946, once more

reopened to United States citizens and business

enterprises owned or controlled by them the lands of

the public domain, the natural resources of the

Philippines, and the operation of the public utilities,

exclusively, but not the acquisition or exploitation of

private agricultural lands, about which not a word is

found in the Parity Amendment..Respondent Quasha's

pretenses can find no support in Article VI of the Trade

Agreement of 1955, known popularly as the LaurelLangley Agreement, establishing a sort of reciprocity

rights between citizens of the Philippines and those of

the United States, couched in the following terms:

ARTICLE VI

2. The rights provided for in Paragraph I may be

exercised, in the case of citizens of the Philippines with

respect to natural resources in the United States which

are subject to Federal control or regulations, only

through the medium of a corporation organized under

the laws of the United States or one of the States

hereof and likewise, in the case of citizens of the

United States with respect to natural resources in

the public domain in the Philippines only through the

medium of a corporation organized under the laws of

the Philippines and at least 60% of the capital stock of

which is owned or controlled by citizens of the United

States. This provision, however, does not affect the

right of citizens of the United States to acquire or own

private agricultural lands in the Philippines or citizens

of the Philippines to acquire or own land in the United

States which is subject to the jurisdiction of the United

States and not within the jurisdiction of any state and

which is not within the public domain. The Philippines

reserves the right to dispose of the public lands in

small quantities on especially favorable terms

exclusively to actual settlers or other users who are its

own citizens. The United States reserves the right to

dispose of its public lands in small quantities on

especially favorable terms exclusively to actual settlers