Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Feed Conversion Ratio

Enviado por

AlbyziaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Feed Conversion Ratio

Enviado por

AlbyziaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Feed conversion ratio

In animal husbandry, feed conversion ratio (FCR), feed

conversion rate, or feed conversion eciency (FCE),

is a measure of an animal's eciency in converting feed

mass into increases of the desired output. For dairy cows,

for example, the output is milk,[1] whereas animals raised

for meat such as beef cows,[2] pigs,[3] chickens,[4] and

sh[5] the output is the mass gained by the animal.

Specically FCR is the mass of the food eaten divided

by the output, all over a specied period.

dierent species may be of little signicance unless the

feeds involved are of similar quality and suitability.

Eciency is customarily expressed as the ratio of useful output to input.[6] Thus, although FCR is commonly

expressed as the ratio of feed mass input to body mass

output, one sometimes sees feed conversion eciency

(FCE) gures, i.e. kg body mass gain per kg feed intake

(or, in the case of dairy animals, kg milk solids per kg

feed intake).

2.2 Pigs

2.1 Cattle

For cattle, a FCR range from less than 5 to more than 20

kg feed dry matter per kg gain may be encountered.[9]

The U.S. pork industry claims to have an FCR of 3.03.2.[10][11]

2.3 Sheep

Being a ratio, FCR is dimensionless, i.e. there are no

Some data for sheep illustrate variations in FCR. A FCR

measurement units associated with FCR.

(kg feed dry matter intake per kg live mass gain) for

lambs is often in the range of about 4 to 5 on highconcentrate rations,[12][13][14] 5 to 6 on some forages of

1 Factors aecting FCR

good quality,[15] and more than 6 on feeds of lesser

quality.[16] On a diet of straw, which has a low metabFCR a function of the animals genetics and age, the qualolizable energy concentration, FCR of lambs may be as

ity of the feed, and the conditions in which the animal is

high as 40.[17] Other things being equal, FCR tends to

kept.[2] As a rule of thumb, the daily FCR is low for young

be higher for older lambs (e.g. 8 months) than younger

animals (when relative growth is large) and increases for

lambs (e.g. 4 months).[14]

older animals (when relative growth tends to level out).

Although FCR is commonly calculated using feed dry

mass, it is sometimes calculated on an as-fed wet mass

basis,[7] (or in the case of grains and oilseeds, sometimes

on a wet mass basis at standard moisture content), with

feed moisture resulting in higher ratios. In cold weather,

metabolizable energy requirements for warmth[8] may result in less net energy of gain obtained from feed. Thus,

when communicating FCR data for a species, it can be

desirable to specify feed moisture content and provide

information regarding breed, age, feed composition, and

environmental conditions under which the ratio applies,

to facilitate data interpretation.

2.4 Poultry

Poultry has a feed conversion ratio of 2 to 1.[18] Chicken

Farmers of Ontario base their Cost of Production on a

FCR of 1.72[19] Tegel Poultry of New Zealand have reported FCR as low as 1.38 on a consistent basis.[20]

2.5 Crickets

Crickets have a low feed conversion ratio of only 1.7.[21]

Cold-blooded organisms expend fewer calories per unit

mass. Fish are a common example of cold-blooded live2.6

stock.

Fish

Farm raised Atlantic salmon have a very good FCR,

about 1.2, according to farmed salmon industry repre2 Conversion ratios for livestock

sentatives. When taking into account the true mass of

material needed to make sh feed, however, the converAnimals that have a low FCR are considered ecient sion ratio increases dramatically to 3:1 according to some

users of feed. However, comparisons of FCR among sources.[22]

1

4 SEE ALSO

Tilapia, typically, 1.6 to 1.8.[18]

2.7

Rabbits

FCR 2.5 to 3.0 on high grain diet and 3.5 to 4.0 on natural

forage diet, without animal-feed grain.[23]

References

[1] Dairy Australia Feed Conversion Eciency

[2] Dan Shike, University of Illinois Beef Cattle Feed Eciency

[3] Pork production

[4] Feed conversion rate for chickens

[5] USAID Technical Bulletin #07: Feed Conversion Ratio

(FCR): How to calculate it and how it is used

[6] See, for example, denition 2a of eciency at

http://education.yahoo.com/reference/dictionary/entry/

efficiency

[7] Snowder, G. D. and L. D. Van Vleck. 2003. Estimates

of genetic parameters and selection strategies to improve

the economic eciency of postweaning growth in lambs.

J. Anim. Sci. 81: 2704-2713

[8] National Research Council (Subcommittee on Environmental Stress). 1981. Eect of environment on nutrient requirements of domestic animals. National Academy

Press, Washington. 168 pp.

[9] National Research Council. 2000. Nutrient Requirements

of Beef Cattle. National Academy Press. 232 pp.

[10] Quick Facts - The Pork Industry at a Glance

[11] Brown, L., Hindmarsh, R., Mcgregor, R., 2001. Dynamic

Agriculture Book Three (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Book

Company, Sydney.

[12] Knott, S. A., B. J. Leury, L. J. Cummins, F. D. Brien and

F. R. Dunshea. 2003. Relationship between body composition, net feed intake and gross feed conversion eciency

in composite sire line sheep. In: Sourant, W. B. and C.

C. Metges (eds.). Progress in research on energy and protein metabolism. EAAP publ. no. 109. Wageningen

[13] Brand, T. S., S. W. P. Cloete and F. Franck. 1991.

Wheat-straw as roughage component in nishing diets of

growing lambs. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci 21: 184-188.

[14] National Research Council. 2007. Nutrient requirements

of small ruminants. National Academies Press. 362 pp.

[15] Fahmy, M. H., J. M. Boucher, L. M. Pose, R. Grgoire,

G. Butler and J. E. Comeau. 1992. Feed eciency, carcass characteristics, and sensory quality of lambs, with or

without prolic ancestry, fed diets with dierent protein

supplements. J. Anim. Sci. 70: 1365-1374

[16] Malik, R. C., M. A. Razzaque, S. Abbas, N. Al-Khozam

and S. Sahni. 1996. Feedlot growth and eciency of

three-way cross lambs as aected by genotype, age and

diet. Proc. Aust. Soc. Anim. Prod. 21: 251-254.

[17] Cronj. P. B. and E. Weites. 1990. Live mass, carcass and

wool growth responses to supplementation of a roughage

diet with sources of protein and energy in South African

Mutton Merino lambs. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 20: 141-168

[18] ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/010/a0701e/a0701e.pdf

[19] http://canadiansmallflockers.blogspot.ca/2013/08/

its-alive.html

[20] http://www.wattagnet.com/154106.html

[21] Collavo, A., Glew, R.H., Huang, Y.S., Chuang, L.T.,

Bosse, R. & Paoletti, M.G. 2005. House cricket smallscale farming. In M.G. Paoletti, ed., Ecological implications of minilivestock: potential of insects, rodents, frogs

and snails. pp. 519544. New Hampshire, Science Publishers.

[22] http://www.mainstreamcanada.ca/

salmon-have-most-efficient-feed-conversion-ratio-fcr-all-farmed-livestock

[23] TNAU Animal Husbandry ::Rabbit

4 See also

Eciency of conversion

Entomophagy

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

5.1

Text

Feed conversion ratio Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feed%20conversion%20ratio?oldid=619282828 Contributors: Ike9898, Bobblewik, Megaversal, Dr.frog, Rich Farmbrough, Gene Nygaard, BD2412, Messenger88, Epipelagic, Corvina, SmackBot, Eliyak, MikeWazowski, MaxEnt, Hobowu, BlindEagle, Diotime, Molly-in-md, PixelBot, DumZiBoT, Jytdog, Addbot, Jarble, Yobot, AnomieBOT,

JackieBot, Disagreeableneutrino, Bellemonde, Hegaldi, N0w8st8s, Walks on Water, Landmann85, KLBot2, BG19bot, Northamerica1000,

DrAdrianTW, Badon, Liam987, Schafhirt, 7Sidz, Chelm261 and Anonymous: 11

5.2

Images

File:FoodWeb.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b3/FoodWeb.jpg License: CC0 Contributors: Own work

Original artist: Thompsma

File:Genomics_GTL_Program_Payoffs.jpg Source:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1c/Genomics_GTL_

Program_Payoffs.jpg License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

5.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

Você também pode gostar

- Nutritional Composition of Housefly Larvae Meal: A Sustainable Protein Source For Animal Production - A ReviewDocumento4 páginasNutritional Composition of Housefly Larvae Meal: A Sustainable Protein Source For Animal Production - A ReviewDoni EdwardAinda não há avaliações

- Feed Intake, Feed Efficiency, Growth and Their Relationship With Kleiber Ratio in Lori-Bakhtiari LambsDocumento8 páginasFeed Intake, Feed Efficiency, Growth and Their Relationship With Kleiber Ratio in Lori-Bakhtiari LambsLuthfiAinda não há avaliações

- Curba de Creștere, Parametrii Sângelui Și Trăsăturile Carcasei Bucilor Angus Hrăniți Cu IarbăDocumento9 páginasCurba de Creștere, Parametrii Sângelui Și Trăsăturile Carcasei Bucilor Angus Hrăniți Cu IarbăTenu FeliciaAinda não há avaliações

- Animashaun - Rasaq@lmu - Edu: A B A A B ADocumento13 páginasAnimashaun - Rasaq@lmu - Edu: A B A A B AvalentineAinda não há avaliações

- Thisis Mo To - 104058Documento23 páginasThisis Mo To - 104058KB Boyles OmamalinAinda não há avaliações

- Tropical Forage Legumes in India - Status and Scope For Animal ProdDocumento23 páginasTropical Forage Legumes in India - Status and Scope For Animal ProdSarbaswarup GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- Asha Ahmed Et - Al Poultery LitterDocumento12 páginasAsha Ahmed Et - Al Poultery Litterashaahmedm2016Ainda não há avaliações

- Effect of Premix and Seaweed Additives On Productive Performance of Lactating Friesian CowsDocumento8 páginasEffect of Premix and Seaweed Additives On Productive Performance of Lactating Friesian CowsOliver TalipAinda não há avaliações

- Ghaljo SheepDocumento10 páginasGhaljo SheepFAHAD KHANAinda não há avaliações

- Nutricion BurroDocumento11 páginasNutricion BurroMontiel Gonzalez GerardoAinda não há avaliações

- Forage Quality Influences Beef Cow Performance and ReproductionDocumento7 páginasForage Quality Influences Beef Cow Performance and ReproductionAgus PriyambodoAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Dabbou 2018Documento10 páginas2 Dabbou 2018Ms. Tuba RiazAinda não há avaliações

- Poultry Research Report 29: I N T R o D U C T I o NDocumento4 páginasPoultry Research Report 29: I N T R o D U C T I o NRucha ZombadeAinda não há avaliações

- Jas 94 Supplement6 111Documento9 páginasJas 94 Supplement6 111Anonymous 9Uq9PO8Ainda não há avaliações

- WEIGHT OF BROILERS FED WITH COMMERCIAL Chapter 2Documento8 páginasWEIGHT OF BROILERS FED WITH COMMERCIAL Chapter 2Plaza IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Growth and Development of Feedlot CattleDocumento21 páginasGrowth and Development of Feedlot CattleHenry JoséAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of Quantitative Feed Restriction and Sex On Carcass Traits, Meat Quality and Meat Lipid Profile of Morada Nova LambsDocumento12 páginasEffects of Quantitative Feed Restriction and Sex On Carcass Traits, Meat Quality and Meat Lipid Profile of Morada Nova LambsluisAinda não há avaliações

- THESIS MANUSCRIPT AutosavedDocumento50 páginasTHESIS MANUSCRIPT AutosavedKivo Al'jahirAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cows: Matt HersomDocumento11 páginasBasic Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cows: Matt HersomSazli KhalilAinda não há avaliações

- Invited Review: An Evaluation of The Likely Effects of Individualized Feeding of Concentrate Supplements To Pasture-Based Dairy CowsDocumento39 páginasInvited Review: An Evaluation of The Likely Effects of Individualized Feeding of Concentrate Supplements To Pasture-Based Dairy CowsleaAinda não há avaliações

- Acta Veterinaria Brasilica: Cassava Foliage in Quail FeedingDocumento7 páginasActa Veterinaria Brasilica: Cassava Foliage in Quail FeedingFevie PeraltaAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Feeding Maize Silage Supplemented With Concentrate / Legume Hay On Carcass Characteristics in Nellore Ram LambsDocumento5 páginasEffect of Feeding Maize Silage Supplemented With Concentrate / Legume Hay On Carcass Characteristics in Nellore Ram LambsVishnu Reddy Vardhan PulimiAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Feeding of Poultry: by Harry W TitusDocumento25 páginasPractical Feeding of Poultry: by Harry W TitusMohammed SakhlainAinda não há avaliações

- A Nutritional Evaluation of Insect Meal As A Sustainable Protein Source For Jumbo Quails: Physiological and Meat Quality ResponsesDocumento4 páginasA Nutritional Evaluation of Insect Meal As A Sustainable Protein Source For Jumbo Quails: Physiological and Meat Quality Responsesmelanie llagasAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition Conference for Feed Manufacturers: University of Nottingham, Volume 7No EverandNutrition Conference for Feed Manufacturers: University of Nottingham, Volume 7Ainda não há avaliações

- Basic Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cows: Dry Matter IntakeDocumento10 páginasBasic Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cows: Dry Matter IntakePerintis RizqiAinda não há avaliações

- 43900-Article Text-193716-4-10-20221031Documento6 páginas43900-Article Text-193716-4-10-20221031architects.collectionAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of A Modern Broiler Line andDocumento10 páginasComparison of A Modern Broiler Line andEduardo ViolaAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition of Range HerbivoresDocumento3 páginasNutrition of Range HerbivoresIlyasAinda não há avaliações

- Feed FormulationDocumento42 páginasFeed Formulationalam zanAinda não há avaliações

- Nutritional Composition of Black Soldier Fly LarvaeDocumento17 páginasNutritional Composition of Black Soldier Fly LarvaemuhabiludinAinda não há avaliações

- Characterising Forages For Ruminant FeedingDocumento9 páginasCharacterising Forages For Ruminant FeedingClaudia SossaAinda não há avaliações

- Wildlife Nutrition and Feeding PDFDocumento15 páginasWildlife Nutrition and Feeding PDFfishman322Ainda não há avaliações

- Cattle Feeding-2016Documento11 páginasCattle Feeding-2016ZerotheoryAinda não há avaliações

- 33 InfluenceofDifferent PDFDocumento9 páginas33 InfluenceofDifferent PDFIJEAB JournalAinda não há avaliações

- The Relationship Between Body Condition Score and Reproductive PerformanceDocumento8 páginasThe Relationship Between Body Condition Score and Reproductive PerformanceL MarsiniAinda não há avaliações

- Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - LincolnDocumento13 páginasDigitalcommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digitalcommons@University of Nebraska - LincolnYagoGAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0032579120308683 MainDocumento11 páginas1 s2.0 S0032579120308683 Mainissa aleAinda não há avaliações

- Selamu PublicationsDocumento10 páginasSelamu Publicationsselamu abraham HemachaAinda não há avaliações

- Nutritional Management of Equine Diseases and Special CasesNo EverandNutritional Management of Equine Diseases and Special CasesBryan M. WaldridgeAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S2352513422001284 MainDocumento13 páginas1 s2.0 S2352513422001284 MainRama BangeraAinda não há avaliações

- Corpin, R-2st Draft-With CommentsDocumento15 páginasCorpin, R-2st Draft-With CommentsKB Boyles OmamalinAinda não há avaliações

- s40104 022 00682 7Documento20 páginass40104 022 00682 7Song ThyyAinda não há avaliações

- ThesisDocumento62 páginasThesisAlmae Delos Santos Borromeo100% (3)

- 2020 - The - Body - Condition - and - Reproduction - Performances - oDocumento8 páginas2020 - The - Body - Condition - and - Reproduction - Performances - oDyah RJAinda não há avaliações

- Feeding, Evaluating, and Controlling Rumen FunctionDocumento38 páginasFeeding, Evaluating, and Controlling Rumen Functionamamùra maamarAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Effects of Fertilization and Supplementary Feed On Growth Performance of Three Fish SpeciesDocumento5 páginasComparative Effects of Fertilization and Supplementary Feed On Growth Performance of Three Fish SpeciesAhmed RashidAinda não há avaliações

- 3.0 Animal Nutrition and ManagementDocumento26 páginas3.0 Animal Nutrition and Managementm jAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of Different Feed On The Growth Rate of Gallus Gallus Domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758)Documento5 páginasEffects of Different Feed On The Growth Rate of Gallus Gallus Domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758)Anonymous izrFWiQAinda não há avaliações

- Specific Swine DietsDocumento31 páginasSpecific Swine DietsVinicius MelloAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0032579120310178 MainDocumento11 páginas1 s2.0 S0032579120310178 MainEduardo ViolaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 6 - Factors Affecting Broiler Performance: A. IntroductionDocumento3 páginasChapter 6 - Factors Affecting Broiler Performance: A. IntroductionSarah Tarala MoscosaAinda não há avaliações

- ThesisDocumento16 páginasThesisJobeth Murcillos40% (5)

- Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle e 974Documento23 páginasNutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle e 974sicario.bingchillingAinda não há avaliações

- Alternative Plant Protein Sources For Pigs and Chickens in The Tropics - Nutritional Value and Constraints A ReviewDocumento23 páginasAlternative Plant Protein Sources For Pigs and Chickens in The Tropics - Nutritional Value and Constraints A ReviewIsmael NeuAinda não há avaliações

- Research Final OutputDocumento35 páginasResearch Final Outputgersyl avilaAinda não há avaliações

- Animal Husbandry-2016Documento6 páginasAnimal Husbandry-2016ZerotheoryAinda não há avaliações

- Carrying - Capacity.v3.apr2009 Updated v4Documento12 páginasCarrying - Capacity.v3.apr2009 Updated v4abdim1437Ainda não há avaliações

- Dry Matter Intake and Energy Balance in The TransiDocumento25 páginasDry Matter Intake and Energy Balance in The TransiXimena Hernandez ArboledaAinda não há avaliações

- Ravaz Index, Cluster ThinningDocumento7 páginasRavaz Index, Cluster ThinningAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- E 2774Documento45 páginasE 2774turbo44Ainda não há avaliações

- Ca 1796 enDocumento254 páginasCa 1796 enHī SāįdAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 - Andrea, Dairy Farm CompostDocumento11 páginas2019 - Andrea, Dairy Farm CompostAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Rockmelon Listeria Outbreak, How To Reduce Your Risk of InfectionDocumento4 páginasRockmelon Listeria Outbreak, How To Reduce Your Risk of InfectionAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Ravaz Index, Vegetative BalanceDocumento9 páginasRavaz Index, Vegetative BalanceAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Fertiliser and Grape YieldDocumento7 páginasFertiliser and Grape YieldAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Vineyard Yield Estimate, Vine BalanceDocumento10 páginasVineyard Yield Estimate, Vine BalanceAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Antioxidant Properties, E PubescensDocumento8 páginasAntioxidant Properties, E PubescensAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Ravaz Index, Wine and GrapesDocumento7 páginasRavaz Index, Wine and GrapesAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Calving Period Affects Cow and Calf Performance in Semi-Arid Areas in ZimbabweDocumento5 páginasCalving Period Affects Cow and Calf Performance in Semi-Arid Areas in ZimbabweAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Turf ManagementDocumento4 páginasTurf ManagementAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Evolutionary Process of Bos Taurus Cattle in Favourable Versus Unfavourable Environments and Its Implications For Genetic SelectionDocumento12 páginasEvolutionary Process of Bos Taurus Cattle in Favourable Versus Unfavourable Environments and Its Implications For Genetic SelectionAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- A Growth Comparison of Ongole and European Cross Cattle Kept by Smallholder Farmers in IndonesiaDocumento4 páginasA Growth Comparison of Ongole and European Cross Cattle Kept by Smallholder Farmers in IndonesiaAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Box Plot 916.full PDFDocumento6 páginasBox Plot 916.full PDFAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- V20n1a05 PDFDocumento9 páginasV20n1a05 PDFAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Measurement of Dietary Fiber - Laboratory MethodDocumento9 páginasMeasurement of Dietary Fiber - Laboratory MethodAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Agronomy DefinitionDocumento4 páginasAgronomy DefinitionAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Plant Growth Analysis, CropDocumento3 páginasPlant Growth Analysis, CropAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - ParaguayDocumento19 páginasFAO Forage Profile - ParaguayAlbyzia100% (1)

- FAO Forage Profile - PeruDocumento18 páginasFAO Forage Profile - PeruAlbyzia0% (1)

- HorticultureDocumento6 páginasHorticultureAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - ColombiaDocumento16 páginasFAO Forage Profile - ColombiaAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles: by Dr. Raul VeraDocumento19 páginasCountry Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles: by Dr. Raul VeraRafael Albán CrespoAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - BrazilDocumento35 páginasFAO Forage Profile - BrazilAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - ChileDocumento20 páginasFAO Forage Profile - ChileAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - UzbekistanDocumento21 páginasFAO Forage Profile - UzbekistanAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - ArgentinaDocumento28 páginasFAO Forage Profile - ArgentinaAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - VietnamDocumento26 páginasFAO Forage Profile - VietnamAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- FAO Forage Profile - Bolivia PDFDocumento18 páginasFAO Forage Profile - Bolivia PDFAlbyziaAinda não há avaliações

- Zero Based Natural Farming in HimachalDocumento2 páginasZero Based Natural Farming in HimachalacaquarianAinda não há avaliações

- Training Design For Napier GrassDocumento3 páginasTraining Design For Napier Grassjeriel repoyloAinda não há avaliações

- Burpee 2022 Digital CatalogDocumento153 páginasBurpee 2022 Digital CatalogKuldeep KoulAinda não há avaliações

- Animal RaisingDocumento40 páginasAnimal RaisingCalAinda não há avaliações

- 2014 Ifa Indonesia IlustreDocumento16 páginas2014 Ifa Indonesia IlustreJesryl PagpaguitanAinda não há avaliações

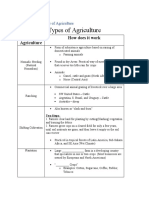

- Types of AgricultureDocumento15 páginasTypes of AgricultureAndres ValleAinda não há avaliações

- Quiz - Module 7Documento7 páginasQuiz - Module 7Alyanna AlcantaraAinda não há avaliações

- 808 Agriculture SQPDocumento5 páginas808 Agriculture SQPAbhyudaya singh TanwarAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter - 1 Economics The Story of Village Palampur: Portal For CBSE Notes, Test Papers, Sample Papers, Tips and TricksDocumento2 páginasChapter - 1 Economics The Story of Village Palampur: Portal For CBSE Notes, Test Papers, Sample Papers, Tips and TricksHarsh kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Rhea Mccool Excel SurveyDocumento7 páginasRhea Mccool Excel SurveyDanielR11Ainda não há avaliações

- Agriculture: One Mark QuestionsDocumento6 páginasAgriculture: One Mark QuestionsMariyam AfsalAinda não há avaliações

- Broiler Poultry Farm Sample Project Report For 1000 ChiksDocumento9 páginasBroiler Poultry Farm Sample Project Report For 1000 Chikssachin d.Ainda não há avaliações

- Checklist For Audit of Aquacultue FarmDocumento2 páginasChecklist For Audit of Aquacultue FarmRama NaikAinda não há avaliações

- Economics Class 9Documento5 páginasEconomics Class 9hweta173Ainda não há avaliações

- Measurement of The Heart Girth and Body LengthDocumento23 páginasMeasurement of The Heart Girth and Body Lengthmargie lumanggayaAinda não há avaliações

- Speech 2 - Adopt Dont ShopDocumento4 páginasSpeech 2 - Adopt Dont Shopapi-497057346Ainda não há avaliações

- Fishing Blues - Henry Thomas - Taj MahalDocumento1 páginaFishing Blues - Henry Thomas - Taj MahalPhil AlexanderAinda não há avaliações

- Aman Kumar - 19020242004 GramophoneDocumento4 páginasAman Kumar - 19020242004 GramophoneAman KumarAinda não há avaliações

- INDIAN OIL Graphical PresentationDocumento3 páginasINDIAN OIL Graphical PresentationHoney AliAinda não há avaliações

- Perception of Farmers On Soil Erosion and ConservationDocumento1 páginaPerception of Farmers On Soil Erosion and ConservationEsa ShantosaAinda não há avaliações

- Narrative Report On SWCMDocumento3 páginasNarrative Report On SWCMRaymond OhAinda não há avaliações

- Seed Priming On LentilDocumento9 páginasSeed Priming On LentilRajendra DaraiAinda não há avaliações

- Hasil Tangkapan Utama Dan Tangkapan Sampingan Bagan Rambo Di Perairan Teluk Lasolo Kabupaten Konawe UtaraDocumento7 páginasHasil Tangkapan Utama Dan Tangkapan Sampingan Bagan Rambo Di Perairan Teluk Lasolo Kabupaten Konawe UtaraFella SupazaeinAinda não há avaliações

- U.S. PEANUT EXPORTS - TOP 10 - From USDA/Foreign Agricultural Service (American Peanut Council)Documento1 páginaU.S. PEANUT EXPORTS - TOP 10 - From USDA/Foreign Agricultural Service (American Peanut Council)Brittany EtheridgeAinda não há avaliações

- System of Wheat IntensificationDocumento25 páginasSystem of Wheat IntensificationPappu Yadav100% (1)

- FARM-Africa Dairy Goat Production HandbookDocumento27 páginasFARM-Africa Dairy Goat Production HandbookFARMAfrica100% (1)

- Hailu Gebre Mariam - PdfabbyyyyDocumento391 páginasHailu Gebre Mariam - PdfabbyyyyBalcha bulaAinda não há avaliações

- Production of Milk in PakistanDocumento8 páginasProduction of Milk in Pakistanmahnoor ashiqAinda não há avaliações

- Dairy FARM-RESUMEDocumento2 páginasDairy FARM-RESUMEShawan SarkarAinda não há avaliações

- 06-Soil Tilth and TillageDocumento51 páginas06-Soil Tilth and Tillageirfandy andy17Ainda não há avaliações