Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

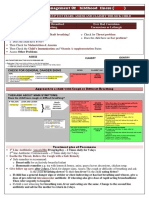

Manage febrile convulsion in children under 6

Enviado por

AriefSuryoWidodoTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Manage febrile convulsion in children under 6

Enviado por

AriefSuryoWidodoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Previous version: Febrile convulsion

About this topic

Have I got the right topic?

Age from 6 months to 6 years

This guidance covers the management of a child who presents having had a febrile convulsion.

This guidance does not cover the emergency management of a child who is still convulsing, or

the management of a child who has epilepsy or other seizure disorder.

There is a separate CKS topic on Epilepsy.

The target audience for this guidance is health care professionals working within the NHS in

England, and providing first contact or primary health care. Patient information from NHS Direct

is intended to be printed and given to the parents of children with this condition, and the Shared

decision making sections are designed to provide a focus for discussion during the consultation

about the treatment options.

Changes

Version 1.0.0, revision planned in 2008.

Last revised in April 2005

October 2006 minor update. Antipyretic prescriptions updated because new doses of

ibuprofen for children are recommend by the British National Formulary. Issued in October 2006.

Previous changes

October 2005 minor technical update. Issued in November 2005.

January 2005 reviewed. Validated in March 2005 and issued in April 2005.

September 2004 minor technical update. Issued September 2004.

July 2001 reviewed. Validated in November 2001 and issued in April 2002.

October 1998 written.

Update

New evidence

Evidence-based guidelines

No new evidence-based guidelines since 1 March 2007.

HTAs (Health Technology Assessments)

No new HTAs since 1 March 2007.

Economic appraisals

No new economic appraisals relevant to England since 1 March 2007.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

No new systematic review or meta-analysis since 1 March 2007.

Primary evidence

No new high quality randomized controlled trials since 1 March 2007.

New policies

No new national policies or guidelines since 1 March 2007.

New safety alerts

No new safety alerts since 1 March 2007.

Changes in product availability

No changes in product availability since 1 March 2007.

Concise knowledge for clinical scenarios

Which therapy?

Consider admission see Should I refer or investigate?

Reassure carers and inform them that:

o

Febrile convulsions do not harm the child. They do not cause brain damage. And, they

are not the same as epilepsy.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Epilepsy can develop later, but this is rare the chance is about 1 in 100 for children

who have had two or more febrile convulsions.

o

Febrile convulsions may recur the chance is about 1 in 3.

Treatment to prevent febrile convulsions is seldom needed, and would only be

started after assessment by a specialist.

Advise on controlling fever in the future.

o

Treating a fever will not prevent febrile convulsions from recurring, but it will ease

symptoms of fever.

o

High temperatures are best reduced by giving paracetamol or ibuprofen, and by

removing excess clothing and bedding.

o

Fanning and tepid sponging can distress the child, and are of no benefit.

Teach parents to manage a recurrent convulsion. They should:

o

Place the child in the recovery position on a soft surface, lying semi-prone with the face

turned to the side. This prevents the inhalation of vomit, keeps the airways open, and

prevents the child from hurting him- or herself.

o

Not force anything into the mouth.

o

Note the time that the convulsion started, and stay with the child.

o

Wait few minutes for the convulsions to stop and then phone the GP or NHS Direct.

o

Dial 999 and request ambulance transport to the nearest hospital accident and

emergency department if the convulsions continue for more than 5 minutes.

Advise on immunization

o

A febrile convulsion only rarely follows a immunization. The excess risks are:

For diphtheria, tetanus toxoid, and whole cell pertussis (DTP)

immunization: 69 children per 100,000 immunizations; risk increased on the

day of vaccination, but not subsequently.

For measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR): 2534 children per 100,000

vaccinations; risk increased 814 days after vaccination.

o

The vaccination schedule should be completed as there is no increased risk of febrile

convulsions with future vaccinations.

o

The risk of neurological and developmental problems is not increased when a febrile

convulsion is associated with a vaccination.

Practical prescribing points

For further information please see the Medicines Compendium (www.medicines.org.uk) or the

British National Formulary (www.bnf.org).

Should I refer or investigate?

Refer?

Most children who have had a febrile convulsion do not need to be admitted.

o

The main concern is the possibility of missing a more serious diagnosis such as

meningitis.

Strongly consider admission for observation, lumbar puncture or treatment if any of the

following factors are present:

o

Age under 18 months (may have meningitis without meningeal signs)

o

Signs of meningitis

o

Child was drowsy before the seizure, or is irritable, systemically unwell or 'toxic'

o

Petechial rash

o

Recent or current treatment with antibiotics (partially treated meningitis may not have

meningeal signs)

o

Complex convulsion (i.e. lasting longer than 10 minutes, or focal, or repeated in the

same episode of illness, or with incomplete recovery within 1 hour)

o

Early review by a doctor not possible

o

Inadequate home circumstances

o

Parents anxious or unable to cope

o

The cause of the fever requires hospital management in its own right

Consider referral if:

o

The diagnosis of febrile convulsion is in doubt.

o

Febrile convulsions have been severe, or complicated and prophylactic treatment might

be indicated.

o

The child might be at increased risk for epilepsy, for example, having a neurological or

developmental condition or because there is a history of epilepsy in parents or siblings.

Investigate?

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Blood glucose. Rule out hypoglycaemia in a child who convulses for more than 5 minutes,

or who is excessively drowsy after the convulsion.

Urine microscopy and culture. If no cause for the fever is found, and the child is not to

be admitted, take a urine specimen (mid-stream urine, clean catch, suprapubic aspirate, or

catheter specimen) for microscopy and culture.

Other investigations should be guided by the cause of the fever rather than by the febrile

convulsion.

Follow-up advice

Prescriptions

Paracetamol s/f susp: 60mg to 120mg up to four times a day

Age from 6 to 11 months

Paracetamol 120mg/5ml oral suspension paediatric sugar free. Take 2.5ml to 5ml every 4 to

6 hours when required for relief of high temperature. Maximum of 4 doses in 24 hours.

Supply 150 ml.

NHS Cost 0.48

OTC Cost 3.49

Licensed use: yes

Paracetamol s/f susp: 120mg to 240mg up to four times a day

Age from 1 year to 6 years

Paracetamol 120mg/5ml oral suspension paediatric sugar free. Take one to two 5ml

spoonfuls every 4 to 6 hours when required for relief of high temperature. Maximum of 4

doses in 24 hours. Supply 300 ml.

NHS Cost 1.30

OTC Cost 6.98

Licensed use: yes

Ibuprofen s/f susp: 50mg three to four times a day

Age from 6 months to 1 year

Ibuprofen 100mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free. Take 2.5ml three to four times a day

when required for relief of high temperature. Do not exceed the stated dose. Supply 100 ml.

NHS Cost 2.69

OTC Cost 3.49

Licensed use: yes

Ibuprofen s/f susp: 100mg three times a day

Age from 1 year 1 month to 3 years 11 months

Ibuprofen 100mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free. Take one 5ml spoonful three times a day

when required for relief of high temperature. Do not exceed the stated dose. Supply 100 ml.

NHS Cost 2.69

OTC Cost 3.49

Licensed use: yes

Ibuprofen s/f susp: 150mg three times a day

Age from 4 to 6 years

Ibuprofen 100mg/5ml oral suspension sugar free. Take 7.5ml three times a day when

required for relief of high temperature. Do not exceed the stated dose. Supply 150 ml.

NHS Cost 2.71

OTC Cost 5.23

Licensed use: yes

Drug rationale

Drugs not included

Intravenous diazepam for seizure termination is not practical for use in primary care.

Midazolam for seizure termination is not included as it is not licensed for use in febrile

convulsions in the UK.

Diazepam in the rectal or oral form for prevention of recurrent febrile convulsions:

this treatment should only be initiated by a specialist. Diazepam in the oral form is not

licensed for use in febrile convulsions.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Other benzodiazepines are not included, as they are not licensed for use in febrile

convulsions.

Oral anticonvulsants for prevention of recurrent febrile convulsions: this treatment

should only be initiated by a specialist.

Drugs included

Paracetamol is an effective and safe antipyretic and analgesic for children.

Ibuprofen is an effective and safe antipyretic and analgesic for children over the age of

12 months.

Shared decision making

Febrile convulsions occur in about 3 in 100 children under the age of 6 years. They

usually last less than 5 minutes.

o

They are not epilepsy.

o

They do not cause brain damage.

Any illness that causes a fever ('temperature') may cause a febrile convulsion. The

common causes are viral infections causing coughs, colds, 'flu, and so on.

Try to keep a fever down when your child has a feverish illness.

o

Paracetamol or ibuprofen reduce fever. Always have some in the home.

o

Remove the child's clothes.

Only one convulsion occurs in most cases. In about 3 in 10 cases another occurs with a

future feverish illness.

Learn how to put a child in the 'recovery position' lay him or her on their side with

their head to one side. Do not put anything into the mouth but remove anything that could

interfere with breathing (such as vomit or food).

Call a doctor or ambulance if the child does not recover quickly or if you feel that the

illness causing the fever is more serious than a common viral infection.

A febrile convulsion very occasionally follows a vaccination.

Detailed knowledge about this topic

Goals and outcome measures

Goals

To make an accurate diagnosis of febrile convulsion

To identify children who should be admitted to hospital for further assessment

To reassure and inform parents about the benign nature of febrile convulsions

To inform parents about the immediate home treatment of possible future febrile

convulsions

Outcome measures

The following outcome measure (selected from a set of outcome measurements for accident and

emergency services) would be suitable for clinical audit in primary care [Armon et al, 2003].

Proportion of children admitted with febrile seizure and no risk factors for meningitis.

o

Target: only admit those children who conform to the admission criteria and those

where the parents or carers cannot be reassured.

Background information

What is it?

What is a febrile convulsion (or febrile seizure)?

A febrile convulsion is a seizure occurring in a child aged 6 months to 5 years, associated

with fever arising from infection or inflammation outside the central nervous system in a

child who is otherwise neurologically normal [Offringa and Moyer, 2001].

A Delphi consensus development process failed to reach agreement on what threshold

temperature could be regarded as defining a fever. The final consensus was that fever

should be assumed to be present if the 'history and examination were indicative' [Armon et

al, 2003].

o

The age limits are arbitrary and should be used as guidelines in clinical practice.

Simple febrile convulsions are isolated, generalized, tonicclonic seizures lasting less

than 1015 minutes.

Complex febrile convulsions last about 1530 minutes, or are focal, or recur during the

febrile illness, or are not followed by full consciousness within an hour.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

What causes febrile convulsions?

The mechanisms causing febrile convulsions are not known. It may not be the fever that

causes the seizure, but release of cytokines, as a consequence of infection, that (a) cause

fever and (b) cause seizures. The risk of febrile convulsions depends upon the age of the

child, so reflecting maturational sensitivity to the cytokines with respect to seizure induction.

Consequently, much of the debate over the presence, height, or rate of rise of the fever

may be irrelevant [Stern, Personal Communication, 2005].

What conditions cause the fever in a child with febrile convulsions?

Viral infections and otitis media are the most common sources of fever in children with febrile

convulsions.

A comprehensive review of the literature identified the conditions usually associated with

febrile convulsions [Armon et al, 2003]. In decreasing order of frequency they are:

o

Viral infections

o

Otitis media

o

Tonsillitis

o

Urinary tract infection

o

Gastroenteritis

o

Lower respiratory tract infection

o

Meningitis

o

Post-immunization

Table 1 presents evidence of a low prevalence of serious bacterial illness in children with

febrile convulsions.

Table 1. Prevalence of serious bacterial illness in 455 children admitted to hospital with a

diagnosis of a first-time febrile convulsion [Trainor et al, 2001].

Test

Number performed

Number positive

Chest X-rays

208

26 pneumonia

Urine cultures

171

10

Blood culture

315

4 (all Streptococcus pneumoniae)

Stool cultures

14

2 (both Shigella sonnei)

Cerebrospinal fluid cultures

135

Bacterial meningitis

A main concern when assessing children who have had a febrile convulsion is to detect and

manage bacterial meningitis.

Bacterial meningitis can be effectively treated, and the consequences of delayed treatment

can be devastating.

The risk of bacterial meningitis is low in children with febrile convulsions [Trainor et al,

2001; Armon et al, 2003]. However, it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of bacterial

meningitis accurately because:

o

Many studies are hospital-based, but some children with febrile convulsions are

managed in primary care.

o

In many children a firm diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is frequently not possible,

either because a lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was not done, or

because the CSF culture and microscopy result was not definitive.

How common is it?

Between 2% and 4% of children have a febrile seizure [Smith, 1994; Armon et al, 2001;

Waruiru and Appleton, 2004].

The peak incidence is at 18 months [Waruiru and Appleton, 2004].

About 4% of febrile convulsions occur in the first 6 months of life, 90% between 6 months

and 3 years, and 6% after 3 years of age [Smith, 1994]. (The cited study had age criteria

that differed from those used in this guidance.)

About 5% of all paediatric medical attendances to an accident and emergency department in

Nottingham were for febrile convulsions [Armon et al, 2001]. About 70% of these children

were admitted.

How do I know my patient has it?

History

Age: 6 months to 5 years old (approximately)

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Convulsion:

o

Duration usually no longer than 36 minutes; class as complex if prolonged more

than 1015 minutes

o

Pattern usually generalized tonicclonic; class as complex if focal

o

Recovery of level of consciousness usually complete within an hour; class as

complex if not fully recovered within an hour

Temperature fever around the time of the convulsion

Previous febrile convulsion class as complex if convulsions recur in the same febrile

illness

Recent immunization it is rare for a febrile convulsion to be precipitated by a

immunization; see Does immunization increase the risk of febrile convulsions and other

complications? in Complications and prognosis.

Examination

Level of consciousness.

Focus of infection. An infection is usually found to be the source of the fever. Check for

viral infections, otitis media, tonsillitis, urinary tract infection (UTI), gastroenteritis, lower

respiratory tract infection, and meningitis.

Investigations

Investigations should be directed towards identifying the source of the fever.

o

UTI. When no focus of infection is found, and admission is not planned, take a urine

sample (mid-stream urine, clean catch, suprapubic aspirate, or catheter specimen) for

microscopy and culture.

o

Bacterial meningitis. A main concern is to identify children with bacterial meningitis.

Criteria for referral for investigation are fully detailed in the section When should I

admit or refer a child who has had a febrile convulsion? in Management issues.

Blood tests, electroencephalograms (EEGs), and neuroimaging are not required in the

evaluation of simple febrile convulsions.

[American Academy of Pediatrics, 1996; Armon et al, 2003]

What else might it be?

Epilepsy

Any other cause of convulsion with fever, or without fever, for example:

o

Meningitis (including partially treated bacterial meningitis)

o

Encephalitis

o

Cerebral palsy with intercurrent infection

o

Hypoglycaemia or other metabolic disorder

o

Neurodegenerative disorders

o

Poisoning

o

Non-accidental shaking injury, rarely

Note that complex febrile convulsions are more likely than simple febrile convulsions to be

provoked by a serious condition. Therefore, suspect serious pathology in a child who has had a

prolonged or focal febrile convulsion, or who has not recovered within an hour of a febrile

convulsion.

[Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association, 1991; Fukuyama et al, 1996]

Complications and prognosis

Complications

Long-term adverse effects are rare.

o

There is no evidence of subsequent impaired intelligence or poorer academic

achievement [Verity et al, 1998].

o

There is a slightly increased risk of epilepsy see under Prognosis below.

Prognosis

What is the risk of recurrence after a febrile convulsion?

Febrile convulsions recur in subsequent febrile illnesses in about 30% of children. Only

9% have more than three seizures [Smith, 1994; Fukuyama et al, 1996].

Recurrence is most common within a year of the first febrile convulsion (70%)

[Fukuyama et al, 1996].

Recurrence is more likely if:

o

The first febrile convulsion occurs under the age of 15 months.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

o

The first convulsion is complex.

o

There is a family history of febrile convulsions or epilepsy in a first-degree relative.

o

The child attends day nursery (due to increased frequency of febrile illnesses).

The recurrence rate is 10% in the absence of these risk factors; 25% with one risk factor;

50% with two risk factors; and approaches 100% with three or more risk factors.

[Knudsen, 1996; Armon et al, 2003]

What is the risk of epilepsy developing after a febrile convulsion?

The risk of subsequent epilepsy is rare but increases with each of the following factors:

o

Neurological abnormalities or developmental delay before the onset of febrile

convulsions

o

Atypical seizures

o

Family history of epilepsy

o

Complex convulsions

In the absence of these risk factors only 1% of children go on to develop epilepsy

(compared with 0.4% of children without a history of febrile convulsion) [Stenklyft and

Carmona, 1994; Knudsen, 1996; Berg et al, 1999].

A Danish study found that children who had febrile convulsions after measles, mumps, and

rubella (MMR) immunization were not at increased risk of later epilepsy (0.23% compared

with 0.60%; not statistically significantly different) [Vestergaard et al, 2004].

Does immunization increase the risk of febrile convulsions and other complications?

Immunization is rarely followed by a febrile convulsion.

o

A large cohort study estimated the risks of a febrile convulsion following immunization

with diphtheria, tetanus toxoid, and whole cell pertussis (DTP) and MMR [Barlow et al,

2001]. Excess rates of febrile convulsions were:

For DTP: 69 children per 100,000 immunizations; risk increased on the day of

immunization, but not subsequently. However, acellular DTPa is now used. We

found no study measuring the rate of febrile convulsions after immunization with

acellular pertussis, but since other reactions are generally fewer than with whole

cell preparations, it is likely to be no higher.

For MMR: 2534 children per 100,000 immunizations; risk increased 814 days

after immunization.

o

A recent study from Denmark of the relationship between MMR and febrile convulsions,

based on a larger number of immunized children than Barlow's gives similar relative

risks. The authors also found that children who had febrile convulsions after MMR

immunization were at slightly increased risk of further febrile convulsions [Vestergaard

et al, 2004].

Immunization-associated febrile convulsions are not likely to cause recurrent

febrile convulsions with future immunizations.

o

Children who had a febrile seizure following immunization were no more likely to have

a subsequent seizure than children who had a febrile seizure not associated with

immunization [Barlow et al, 2001].

Immunization-associated febrile convulsions are not likely to cause

neurobehavioural disorders.

o

The relative risk of developing one or more learning or developmental disabilities after

a febrile convulsion associated with immunization was 0.56 (95% confidence interval

0.07 to 4.2) [Barlow et al, 2001].

Management issues

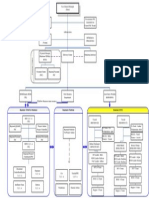

Overview of management

Reassure carers that febrile convulsions do not harm the child.

Advise on controlling fever in the future: an antipyretic, cool clothing, no physical cooling.

Teach parents to manage a recurrent convulsion: recovery position, nothing forced into

mouth.

Recommend that immunization schedules be completed.

Admit children who need observation, investigation, or treatment of the underlying

condition: the main concern is to detect children at increased risk of meningitis.

Consider referral for children who are at increased risk for epilepsy.

When should I admit or refer a child who has had a febrile convulsion?

Criteria for admission

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

Most children with a first febrile convulsion do not need to be admitted. The main

concern is the possibility of missing a more serious diagnosis such as meningitis.

Strongly consider admission for observation, lumbar puncture or treatment if any of the

following factors are present:

o

Age under 18 months (may have meningitis without meningeal signs)

o

Signs of meningitis (neck stiffness; photophobia; Kernig's sign; Brudzinski's signs;

bulging fontanelle; depressed level of consciousness, for example, Glasgow Coma scale

< 15 at 1 hour after the convulsion):

Kernig's sign: pain restricts leg straightening when supine and holding the thigh

flexed to a right angle

Brudzinski sign 1 (contralateral reflex, contralateral sign): when lying supine,

passive flexion of one leg results in a similar movement in the opposite leg

Brudzinski sign 2 (neck sign): knees and hips flex involuntarily when the neck is

flexed while supine

Test for meningism gently and considerately, as this can be painful

o

Child was drowsy before the seizure, or is irritable, systemically unwell or

'toxic'

o

Petechial rash

o

Recent or current treatment with antibiotics (because partially treated meningitis

may not have meningeal signs)

o

Complex convulsion (i.e. lasting longer than 10 minutes; or with focal features, e.g.

jerking affecting only one limb; or repeated in the same episode of illness; or with

incomplete recovery within 1 hour)

o

Early review by a doctor not possible

o

Inadequate home circumstances

o

Carer anxious or unable to cope

o

The cause of the fever requires hospital management in its own right

[Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association, 1991; American Academy of

Pediatrics, 1999; Armon et al, 2003; Warden et al, 2003; Waruiru and Appleton, 2004]

When should I refer a child who has had a febrile convulsion?

Consider referral if:

The diagnosis of febrile convulsion is in doubt.

The cause of the fever is in doubt.

Febrile convulsions have been severe, or complicated and prophylactic treatment might be

indicated.

The child might be at increased risk for epilepsy, for example, having a neurological or

developmental condition or because there is a history of epilepsy in parents or siblings

[Fukuyama et al, 1996].

The parents require additional reassurance that the child is not at risk of dying or of serious

complications.

How do I manage the fever?

Diagnose the cause of the fever

Seek the source of the fever.

o

Consider the following differential diagnosis: viral infection, otitis media, tonsillitis,

urinary tract infection (UTI), gastroenteritis, lower respiratory tract infection,

meningitis, post-immunization, post-ictal fever [Baumer and Paediatric Accident and

Emergency Research Group, 2004].

When no focus of infection is found, and admission is not planned, a urine sample should be

taken for dipstick test, microscopy, and culture [Armon et al, 2003].

o

Ideally the urine specimen should be from a suprapubic aspirate or catheter sample,

which may need to be obtained in hospital. If this is impractical, urine may be collected

by bag, mid-stream urine, clean catch, or pad; bear in mind that contamination of the

urine may make interpretation of culture results unreliable [Verrier-Jones, Personal

Communication, 2005]. The likelihood of urinary tract infection is very high if a dipstick

test of the urine is positive for both nitrite and leucocyte esterase [NHS CRD, 2004].

Treat the fever to ease symptoms

Prescribe paracetamol or ibuprofen.

Remove excessive clothing and bedding.

Avoid physical methods such as fanning, cold bathing, and tepid sponging their use is

controversial as they are felt to cause some discomfort and minimal benefit.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

[Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association, 1991; Fukuyama et al, 1996;

Meremikwu and Oyo-Ita, 2003; Watts et al, 2003]

What measures should I consider to prevent febrile convulsions?

Treatment to prevent recurrence of febrile convulsions is rarely necessary and

should only be prescribed after specialist assessment.

Treating fevers with antipyretics does not prevent febrile convulsions [Offringa and

Moyer, 2001].

Intermittent rectal diazepam given at the onset of a fever to prevent febrile convulsions

may be a suitable option, depending on home circumstances, for a child at high risk of

recurrence of severe or complicated seizures.

o

Diazepam (oral and rectal) at relatively high doses may prevent febrile convulsions in

subsequent illness if given at the onset of a febrile episode [Offringa and Moyer, 2001;

Masuko et al, 2003].

o

Rectal diazepam is safe for home use, providing parents are properly educated in its

use [Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association, 1991; Knudsen,

1996].

o

Adverse effects have been reported with intermittent use of diazepam; these included

ataxia (31.1%), lethargy (28.8%), and irritability (24.4%), but lasted no more than

36 hours [Verrotti et al, 2004].

o

Treatment to prevent febrile seizures should only be prescribed after specialist

assessment.

Continuous prophylaxis is controversial. Anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital are

minimally effective in preventing febrile convulsions on average 8 children would need to

be treated for 2 years to prevent 1 febrile convulsion and the benefits of prophylaxis are

outweighed by the risk of adverse effects [Offringa and Moyer, 2001].

No treatment is available to reduce the rare risk of subsequent epilepsy.

Immunization is not contraindicated after a febrile convulsion.

o

There is evidence to suggest that immunizations do not increase the risk of recurrent

febrile convulsions [Offringa and Moyer, 2001].

How should I counsel parents?

Inform parents that:

o

Although febrile convulsions are frightening to watch, they are not harmful to the child,

do not cause brain damage, and will not cause the child to die.

o

The child will be sleepy for up to an hour after the convulsion.

o

Febrile convulsions are not the same as epilepsy.

o

Epilepsy can develop later, but this is rare the chance is about 1 in 100 for children

who have had two or more febrile convulsions.

o

Febrile convulsions may recur about 1 in 3 children will have another febrile

convulsion.

o

Treatment to prevent febrile convulsions recurring is seldom necessary, nor is it worth

having to put up with the side effects or taking the risk of serious adverse effects.

o

If the child is at high risk for further seizures (e.g. having a neurological condition or

because there is a family history of epilepsy in parents or siblings), referral to a

specialist might be useful.

Advise parents on controlling high temperatures

o

The aim of controlling fever is to ease symptoms, not to prevent febrile convulsions.

o

High temperature is best reduced by giving paracetamol or ibuprofen, and by removing

excessive clothing and bedding.

o

Fanning and tepid sponging are likely to cause discomfort and are of little benefit.

Teach parents to manage a recurrent convulsion. They should:

o

Place the child in the recovery position on a soft surface, lying semi-prone with the face

turned to the side. This prevents the inhalation of vomit, keeps the airways open, and

prevents the child from hurting him- or herself.

o

Not force anything into the mouth.

o

Note the time that the convulsion started, and stay with the child.

o

Wait a few minutes for the convulsions to stop, then phone their GP or NHS Direct.

o

Dial 999 if the convulsions continue more than 5 minutes, and request ambulance

transport to the nearest hospital accident and emergency department.

Counsel parents about immunization

o

Immunization is still advised after a febrile convulsion, even if, as rarely happens, the

febrile convulsion followed a immunization.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

[Baumer et al, 1981; Gordon et al, 2001; Huang, 2001; Parmar et al, 2001; Huang et al, 2002;

Armon et al, 2003; Warden et al, 2003; Waruiru and Appleton, 2004]

References

NHS staff in England can link, free of charge, from references to the full text journal

articles by clicking on [NHS Athens Full-text]. You will need an NHS Athens password to

access these resources. Click here for Athens registration.

All references with links to [Free Full-text] are freely available online to users in

England and Wales. This includes the full text of Department of Health papers and Cochrane

Library reviews.

1

2

3

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

American Academy of Pediatrics (1996) Practice parameter: the neurodiagnostic evaluation

of the child with a first simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics 97(5), 769-772.

American Academy of Pediatrics (1999) Practice parameter: long-term treatment of the

child with simple febrile seizures. Pediatrics 103(6 Pt 1), 1307-1309. [Free Full-text]

Armon, K., Stephenson, T., Gabriel, V. et al. (2001) Determining the common medical

presenting problems to an accident and emergency department. Archives of Disease in

Childhood 84(5), 390-392. [NHS Athens Full-text]

Armon, K., Stephenson, T., Hemingway, P. et al. (2003) An evidence and consensus based

guideline for the management of a child after a seizure. Emergency Medicine Journal 20(1),

13-20.

Barlow, W.E., Davis, R.L., Glasser, J.W. et al. (2001) The risk of seizures after receipt of

whole-cell pertussis or measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. New England Journal of

Medicine 345(9), 656-661. [NHS Athens Full-text]

Baumer, J.H. and Paediatric Accident and Emergency Research Group (2004) Evidence

based guideline for post-seizure management in children presenting acutely to secondary

care. Archives of Disease in Childhood 89(3), 278-280.

Baumer, J.H., David, T.J., Valentine, S.J. et al. (1981) Many parents think their child is

dying when having a first febrile convulsion. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology

23(4), 462-464.

Berg, A.T., Shinnar, S., Levy, S.R. and Testa, F.M. (1999) Childhood-onset epilepsy with

and without preceding febrile seizures. Neurology 53(8), 1742-1748.

Fukuyama, Y., Seki, T., Ohtsuka, C. et al. (1996) Practical guidelines for physicians in the

management of febrile seizures. Brain & Development 18(6), 479-484.

Gordon, K.E., Dooley, J.M., Camfield, P.R. et al. (2001) Treatment of febrile seizures: the

influence of treatment efficacy and side-effect profile on value to parents. Pediatrics 108(5),

1080-1088. [Free Full-text]

Huang, M.C. (2001) Parental concerns for the child with febrile convulsion: long-term effects

of educational interventions. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 103(5), 288-293.

Huang, M.C., Liu, C.C., Huang, C.C. and Thomas, K. (2002) Parental responses to first and

recurrent febrile convulsions. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 105(4), 293-299.

Knudsen, F.U. (1996) Febrile seizures - treatment and outcome. Brain & Development

18(6), 438-449.

Masuko, A.H., Castro, A.A., Santos, G.R. et al. (2003) Intermittent diazepam and continuous

phenobarbital to treat recurrence of febrile seizures: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria 61(4), 897-901.

Meremikwu, M. and Oyo-Ita, A. (2003) Physical methods for treating fever in children

(Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

www.thecochranelibrary.com [Accessed: 01/12/2004]. [Free Full-text]

NHS CRD (2004) Diagnosing urinary tract infection (UTI) in the under fives. Effective Health

Care 8(6), 1-12. [Free Full-text]

Offringa, M. and Moyer, V.A. (2001) Evidence based paediatrics: evidence based

management of seizures associated with fever. British Medical Journal 323(7321), 11111114. [Free Full-text]

Parmar, R.C., Sahu, D.R. and Bavdekar, S.B. (2001) Knowledge, attitude and practices of

parents of children with febrile convulsion. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 47(1), 19-23.

[Free Full-text]

Royal College of Physicians and the British Paediatric Association (1991) Guidelines for the

management of convulsions with fever. British Medical Journal 303(6803), 634-636. [Free

Full-text]

Smith, M.C. (1994) Febrile seizures. Recognition and management. Drugs 47(6), 933-944.

Stenklyft, P.H. and Carmona, M. (1994) Febrile seizures. Emergency Medicine Clinics of

North America 12(4), 989-999.

Stern, C. (2005) Personal communication. The mechanisms of febrile convulsions.

Consultant in Neurology, St. Thomas' Hospital: London.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Previous version Febrile convulsion

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Trainor, J.L., Hampers, L.C., Krug, S.E. and Listernick, R. (2001) Children with first-time

simple febrile seizures are at low risk of serious bacterial illness. Academic Emergency

Medicine 8(8), 781-787. [NHS Athens Full-text]

Verity, C.M., Greenwood, R. and Golding, J. (1998) Long-term intellectual and behavioral

outcomes of children with febrile convulsions. New England Journal of Medicine 338(24),

1723-1728. [NHS Athens Full-text]

Verrier-Jones, K. (2005) Personal communication. Diagnosis of urinary tract infection in

children presenting with a febrile convulsion. Reader in Child Health, University of Cardiff:

Cardiff, UK.

Verrotti, A., Latini, G., di Corcia, G. et al. (2004) Intermittent oral diazepam prophylaxis in

febrile convulsions: its effectiveness for febrile seizure recurrence. European Journal of

Paediatric Neurology 8(3), 131-134.

Vestergaard, M., Hviid, A., Madsen, K.M. et al. (2004) MMR vaccination and febrile seizures:

evaluation of susceptible subgroups and long-term prognosis. Journal of the American

Medical Association 292(3), 351-357.

Warden, C.R., Zibulewsky, J., Mace, S. et al. (2003) Evaluation and management of febrile

seizures in the out-of-hospital and emergency department settings. Annals of Emergency

Medicine 41(2), 215-222.

Waruiru, C. and Appleton, R. (2004) Febrile seizures: an update. Archives of Disease in

Childhood 89(8), 751-756.

Watts, R., Robertson, J. and Thomas, G. (2003) Nursing management of fever in children: a

systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Practice 9(1), S1-S8.

Patient information

Patient information from NHS Direct:

Febrile convulsions

Browse all NHS Direct patient information

Quick Reference Guide

Paracetamol and ibuprofen use in children

Quick Reference Guides are in Adobe PDF format. To view PDF files, You can download Adobe

Reader which is freely available from the Adobe website at www.adobe.co.uk.

Quick Reference Guides will open in a new browser window.

This PRODIGY guidance topic is obsolete and has been replaced by a CKS Topic Review.

Please visit www.cks.library.nhs.uk to find the latest version.

Você também pode gostar

- NCLEX: Pharmacology for Nurses: 100 Practice Questions with Rationales to help you Pass the NCLEX!No EverandNCLEX: Pharmacology for Nurses: 100 Practice Questions with Rationales to help you Pass the NCLEX!Nota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)

- EDTA IV and Oral Chelation ProtocolDocumento10 páginasEDTA IV and Oral Chelation ProtocolAla MakotaAinda não há avaliações

- IMCIDocumento42 páginasIMCIMichael Anthony ErmitaAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiovascular HealthDocumento20 páginasCardiovascular HealthChrrieAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Otitis Media - 6435 SOAPDocumento21 páginasAcute Otitis Media - 6435 SOAPMelinda Powell100% (1)

- Convulsions (Seizures) : Prof. Dr. Shahenaz M. HusseinDocumento26 páginasConvulsions (Seizures) : Prof. Dr. Shahenaz M. HusseinAriefSuryoWidodo100% (1)

- IMCI Guideline-2023 HeshamElsayedDocumento57 páginasIMCI Guideline-2023 HeshamElsayedMalak Rageh100% (2)

- Maternal ATIDocumento6 páginasMaternal ATIGeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Postterm Pregnancy Risks and ManagementDocumento29 páginasPostterm Pregnancy Risks and ManagementNur Agami100% (1)

- Acute Respiratory Tract Infection Guideline: PediatricsDocumento2 páginasAcute Respiratory Tract Infection Guideline: PediatricsArie NofariyandiAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric RemediationDocumento5 páginasPediatric RemediationAlvin L. Rozier67% (3)

- CAUTIDocumento46 páginasCAUTImahesh sivaAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI UpdatedDocumento5 páginasIMCI UpdatedMalak RagehAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Surgical NursingDocumento6 páginasMedical Surgical NursingzemmiphobiaAinda não há avaliações

- Infant Colic, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo EverandInfant Colic, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsAinda não há avaliações

- PN Pharmacology Online Practice 2014 BDocumento5 páginasPN Pharmacology Online Practice 2014 BTee Wood67% (3)

- Acute Care PathwaysDocumento78 páginasAcute Care PathwaysRachel Niu IIAinda não há avaliações

- PaediatricDocumento423 páginasPaediatricmuntaserAinda não há avaliações

- Advantages of Breastfeeding Over Formula FeedingDocumento11 páginasAdvantages of Breastfeeding Over Formula FeedingZweAinda não há avaliações

- Nausea Vomiting in PregnancyDocumento13 páginasNausea Vomiting in PregnancyVicko SuswidiantoroAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation of Alina CommunityDocumento29 páginasPresentation of Alina CommunitySmita PandeyAinda não há avaliações

- Pneumonia PDFDocumento3 páginasPneumonia PDFSari RamadhanAinda não há avaliações

- Welcome RSVDocumento32 páginasWelcome RSVapi-260357356Ainda não há avaliações

- Untitled DocumentDocumento42 páginasUntitled Documentallkhusairy6tuansiAinda não há avaliações

- Paediatric Protocols FinalDocumento33 páginasPaediatric Protocols FinalAbdulkarim Mohamed AbdallaAinda não há avaliações

- Convulsions in PregnancyDocumento5 páginasConvulsions in PregnancyĶHwola ƏľsHokryAinda não há avaliações

- Bronchial Asthma and Acute AsthmaDocumento38 páginasBronchial Asthma and Acute AsthmaFreddy KassimAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI NewDocumento81 páginasIMCI NewBianca de GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric OSCEs 2016 ModifiedDocumento113 páginasPediatric OSCEs 2016 ModifiedAbdulKhaleq AlkadimiAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Guideline for Febrile Seizure Evaluation in ChildrenDocumento18 páginasClinical Guideline for Febrile Seizure Evaluation in Childrenkara_korum100% (1)

- IMCI - ContentDocumento13 páginasIMCI - ContentMarianne Daphne GuevarraAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI Revised For CHN 1 NEW 1st Sem 2022Documento82 páginasIMCI Revised For CHN 1 NEW 1st Sem 2022Aech Euie100% (1)

- Post Assessment PediatricsDocumento4 páginasPost Assessment Pediatricscuicuita100% (4)

- Summary of The Alberta Clinical Practice Guideline, March 2003Documento2 páginasSummary of The Alberta Clinical Practice Guideline, March 2003Irind PcAinda não há avaliações

- Imci UpdatesDocumento37 páginasImci UpdateskristiandiorcapiliAinda não há avaliações

- Imci PPT 6th ExamDocumento50 páginasImci PPT 6th ExamGladys YaresAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Respiratory InfectionDocumento68 páginasAcute Respiratory InfectionArun GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Paed Anaesthetic 01Documento3 páginasPaed Anaesthetic 01Mafeitzeral MamatAinda não há avaliações

- AANP PRACTICE QUESTIONS AND ANSWERSDocumento32 páginasAANP PRACTICE QUESTIONS AND ANSWERSanahmburu966Ainda não há avaliações

- DR - Marian Exam 21/4/2021Documento7 páginasDR - Marian Exam 21/4/2021Aseel AlsheeshAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Medical Complications in Inpatient Therapeutic Care Module 6bDocumento36 páginasManagement of Medical Complications in Inpatient Therapeutic Care Module 6bDexter MasongsongAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric DrugDocumento68 páginasPediatric DrugHossen AliAinda não há avaliações

- Management of ARIDocumento33 páginasManagement of ARISam christenAinda não há avaliações

- 10195a77-f68f-43b2-82f2-060d896d8450Documento10 páginas10195a77-f68f-43b2-82f2-060d896d8450rdwhkhaldAinda não há avaliações

- Bronchiolitis Starship GuidelineDocumento7 páginasBronchiolitis Starship Guidelinechicky111Ainda não há avaliações

- Case Management of Ari at PHC LevelDocumento29 páginasCase Management of Ari at PHC Levelapi-3823785Ainda não há avaliações

- Frequent Passing: 1. Diarrhea Diarrhea Is TheDocumento13 páginasFrequent Passing: 1. Diarrhea Diarrhea Is TheDavid HosamAinda não há avaliações

- Child Infection 3Documento22 páginasChild Infection 3Bishnoi MaheshAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric Case Sheet: IdentificationDocumento10 páginasPediatric Case Sheet: Identificationabnamariq17Ainda não há avaliações

- Under 5s Asthma Action PlanDocumento5 páginasUnder 5s Asthma Action Planasimnaqvi2003Ainda não há avaliações

- Febrile Convulsion: Background To ConditionDocumento4 páginasFebrile Convulsion: Background To ConditionAbdelrahmanEmbabiAinda não há avaliações

- ATI Proctored Exam Pediatrics StudyDocumento5 páginasATI Proctored Exam Pediatrics Studyianshirow834Ainda não há avaliações

- IMCI Basic Pedia 2015 PPTDocumento77 páginasIMCI Basic Pedia 2015 PPTCharles DoradoAinda não há avaliações

- Drugs For The Management of Dental Problems During COVID-19 PandemicDocumento8 páginasDrugs For The Management of Dental Problems During COVID-19 PandemicMedical TubeAinda não há avaliações

- H1N1 Guidelines KeralaDocumento5 páginasH1N1 Guidelines Keralausa01Ainda não há avaliações

- CasesDocumento25 páginasCasesfatemaAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI-sverreview 2011versionPDFDocumento45 páginasIMCI-sverreview 2011versionPDFNicole PageAinda não há avaliações

- Drug StudyDocumento16 páginasDrug StudyJhann0% (1)

- Cephalexin: Adjust-A-Dose (For All Indications)Documento3 páginasCephalexin: Adjust-A-Dose (For All Indications)HannaAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Pneumonia in The Child 2 To 59 Months of AgeDocumento5 páginasManagement of Pneumonia in The Child 2 To 59 Months of AgeOlive IrawadiAinda não há avaliações

- 1215 LHCC LA - CP.MP.34 Hyperemesis Gravidarum TreatmentDocumento9 páginas1215 LHCC LA - CP.MP.34 Hyperemesis Gravidarum TreatmentSatriyo Krisna PalgunoAinda não há avaliações

- IMCI TECHNICAL UPDATES: The KEY To Your Success!! Pls..... Read.. Read.. Read.Documento10 páginasIMCI TECHNICAL UPDATES: The KEY To Your Success!! Pls..... Read.. Read.. Read.Kim RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Care for Pregnant Women with Medical ComplicationsDocumento11 páginasNursing Care for Pregnant Women with Medical ComplicationsKimberly Clariz Zamora AsidoAinda não há avaliações

- Manage Child Cough, Breathing IssuesDocumento18 páginasManage Child Cough, Breathing IssuesNithu NithuAinda não há avaliações

- Explanation StationDocumento4 páginasExplanation StationjsdlzjAinda não há avaliações

- Delivery Center O-chart-V1 0 Cj-EjDocumento1 páginaDelivery Center O-chart-V1 0 Cj-EjAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Energy Systems Slide ShowDocumento25 páginasEnergy Systems Slide ShowAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Reemphasizing of Not Recruiting Manpower From Each OtherDocumento1 páginaReemphasizing of Not Recruiting Manpower From Each OtherAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- KPI OSS Single Site and Cluster StrategiesDocumento1 páginaKPI OSS Single Site and Cluster StrategiesAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- The Thienopyridine Derivatives (Platelet Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Antagonists), Pharmacology and Clinical DevelopmentsDocumento8 páginasThe Thienopyridine Derivatives (Platelet Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Antagonists), Pharmacology and Clinical DevelopmentsAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Prolonged Horner's Syndrome After Interscalene Block: A Case ReportDocumento3 páginasProlonged Horner's Syndrome After Interscalene Block: A Case ReportAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Arief Suryo - Attested CertificateDocumento1 páginaArief Suryo - Attested CertificateAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- 2g LST License NewDocumento144 páginas2g LST License NewAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Delivery Center O-chart-V1 0 Cj-EjDocumento1 páginaDelivery Center O-chart-V1 0 Cj-EjAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Brown-Sequard Syndrome Associated With Horner's Syndrome After ADocumento4 páginasBrown-Sequard Syndrome Associated With Horner's Syndrome After AAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Early Identification of Bulbar Symptoms in ALSDocumento104 páginasEarly Identification of Bulbar Symptoms in ALSAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Monthly Charge MauveeDocumento1 páginaMonthly Charge MauveeAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- FebrileDocumento5 páginasFebrileTaufik IndrawanAinda não há avaliações

- Horner Syndrome As A Complication of Central VenousDocumento3 páginasHorner Syndrome As A Complication of Central VenousAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Why Is Patrick Paralyzed?: Maureen KnabbDocumento36 páginasWhy Is Patrick Paralyzed?: Maureen KnabbAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-4Documento15 páginasAmyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-4AriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- ALS Canada Research FundingDocumento17 páginasALS Canada Research FundingAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Authors: Vanessa Nowosad and Genevieve Go Citations in APA FormatDocumento16 páginasAmyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Authors: Vanessa Nowosad and Genevieve Go Citations in APA FormatAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Ali Nasim MD Fellow, Neuroradiology Division at UNCDocumento22 páginasAmyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Ali Nasim MD Fellow, Neuroradiology Division at UNCAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Blockade of Adenosine DiphospateDocumento7 páginasBlockade of Adenosine DiphospateAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Common Questions About ALS ..14 Who Was Lou Gehrig?.................................................... 17 Recommended Steps After Diagnosis .19Documento7 páginasCommon Questions About ALS ..14 Who Was Lou Gehrig?.................................................... 17 Recommended Steps After Diagnosis .19AriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- 12.12.07 HoneycuttDocumento30 páginas12.12.07 HoneycuttRakasiwi GalihAinda não há avaliações

- Pembelian SFDocumento1 páginaPembelian SFAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- 2G SSV MethodologyDocumento1 página2G SSV MethodologyAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- CV Darvis Aurian Saputra Telecom EngineerDocumento5 páginasCV Darvis Aurian Saputra Telecom EngineerAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal DataDocumento2 páginasCurriculum Vitae: Personal DataAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- RNO 3G - Agung Hendra Gunawan CVDocumento4 páginasRNO 3G - Agung Hendra Gunawan CVAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Faizal Akbar Griya Prima Tonasa D1/7 Kel - Pai Kec. Biringkanaya Makassar PhoneDocumento3 páginasFaizal Akbar Griya Prima Tonasa D1/7 Kel - Pai Kec. Biringkanaya Makassar PhoneAriefSuryoWidodoAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Proving: The Base of Homoeopathic System of Medicine As Well As The Vital Force of HomoeopathyDocumento2 páginasDrug Proving: The Base of Homoeopathic System of Medicine As Well As The Vital Force of Homoeopathyskandan s kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Prevention of Dental Caries 1Documento38 páginasPrevention of Dental Caries 1Nuran AshrafAinda não há avaliações

- Uri Flush 3 Liquid Stones ProblemDocumento4 páginasUri Flush 3 Liquid Stones ProblemSourabh KoshtaAinda não há avaliações

- The Surgical WardDocumento8 páginasThe Surgical Wardجميلة المعافيةAinda não há avaliações

- CHP 1 Worksheet SPRG 18Documento3 páginasCHP 1 Worksheet SPRG 18Gregory ChildressAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence and Impact of Pain Among Older Adults in The United StatesDocumento9 páginasPrevalence and Impact of Pain Among Older Adults in The United StatesLucas TarquiAinda não há avaliações

- 1.structure of The TeethDocumento5 páginas1.structure of The TeethCălin PavelAinda não há avaliações

- Joseph Constantine Carpue and The Bicentennial of The Birth of Modern Plastic SurgeryDocumento11 páginasJoseph Constantine Carpue and The Bicentennial of The Birth of Modern Plastic Surgerysmansa123Ainda não há avaliações

- Antiprotozoal and Antihelminthic Drugs - HandoutDocumento21 páginasAntiprotozoal and Antihelminthic Drugs - HandoutdonzAinda não há avaliações

- Work-Based Learning in Nursing Education: The Value of PreceptorshipsDocumento5 páginasWork-Based Learning in Nursing Education: The Value of Preceptorshipssyamsul anwarAinda não há avaliações

- AspirinDocumento61 páginasAspirinMarta Halim100% (1)

- EMS Transfer of Care Form: For Stroke, Chest Pain, Trauma or Altered Mental StatusDocumento2 páginasEMS Transfer of Care Form: For Stroke, Chest Pain, Trauma or Altered Mental StatusAna ManoliuAinda não há avaliações

- Operation Humanitarian Network During The COVID 19 PandemicDocumento17 páginasOperation Humanitarian Network During The COVID 19 PandemicLyzaline MulaAinda não há avaliações

- Reaction PaperDocumento2 páginasReaction PaperSherylou Kumo SurioAinda não há avaliações

- Medical EthicsDocumento27 páginasMedical Ethicspriyarajan007Ainda não há avaliações

- Improving Dental Access in the Red River ValleyDocumento6 páginasImproving Dental Access in the Red River ValleyLuis GuevaraAinda não há avaliações

- Unsafe Abortion PDFDocumento66 páginasUnsafe Abortion PDFIntan Wahyu CahyaniAinda não há avaliações

- Genitourinary Syndrome of MenopauseDocumento8 páginasGenitourinary Syndrome of Menopauserizky ferdina kevinAinda não há avaliações

- Syphilis in Pregnancy: Clinical Expert SeriesDocumento15 páginasSyphilis in Pregnancy: Clinical Expert SeriesWindy MuldianiAinda não há avaliações

- ICM Standard List For Competency-Based Skills TrainingDocumento40 páginasICM Standard List For Competency-Based Skills TrainingRima SartikaAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy and HeartDocumento53 páginasPregnancy and HeartgibreilAinda não há avaliações

- BibliographyDocumento5 páginasBibliographyhoneyworksAinda não há avaliações

- 02 Family Oriented Medical RecordDocumento4 páginas02 Family Oriented Medical RecordFernandez-De Ala NicaAinda não há avaliações

- The Pathophysiology of PPROMDocumento2 páginasThe Pathophysiology of PPROMNano KaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Management TemplateDocumento5 páginasCase Management TemplateEncik AhmadAinda não há avaliações