Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

BGH Assignment 4 Museum Report

Enviado por

kartikeyajainTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

BGH Assignment 4 Museum Report

Enviado por

kartikeyajainDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

INTRODUCTION

The Museum of Anatomy & Pathology (MAP) in Manipal houses an

extensive collection of biological, i.e. human and animal specimens for

display in a sprawling, swanky space. It seems to be a proud exhibition of

the excellence in the medical sciences pursued at the Kasturba Medical

College of Manipal University. This is apparent in the language of its

description on the university website [] the museum boasts of over

3,000 specimens and samples of things anatomical, including the skulls of

an elephant and a whale, and the long skeleton of a King Cobra

(Anatomy Museum Overview n.d.).

The larger idea behind the project is seemingly, to make accessible the

vast bodies of knowledge related to anatomy, biology and pathology to

the general public, outside of these highly specialized disciplines.

There are two broad aspects that have come to light with my visit to this

museum that I would like to talk about in this piece. First, is the aspect of

display or representation itself of the various bodies (and body parts) in a

museum setup, and the gamut of questions that raises regarding

knowledge, and underlying narratives that come through within that

space. Second, is that of the affective or aesthetic spirit that creeps into

ones experience of, what is on the surface, supposed to be a sterile

educational experience for the visitor that is in part, induced by the

manner of presentation of and within the space.

The museum starts with a section on comparative anatomy with

specimens on display of various animals, as mentioned before, these are

skulls displayed in shelves along with cross sections of various birds,

mammals and reptiles preserved in formaldehyde. Some of the skulls are

newly painted in an odd colour scheme. For instance, the elephant tusk is

innocuously painted white while, on the other hand, there is a display of

an old man in typical Indian sadhu garb of orange robes, with skin painted

dark brown and a fake beard. This display oddly, does not have any

description - which makes one question its placement in the museum.

There is a similar obsession apparent throughout the rest of the museum

with representing specimens in a particular way, by further intervening on

them via painting (among other things), it seems, to either make them fit

for presentation (whatever that may mean) or also, to indicate a certain

status of health or disease through various colour tropes associated with

the many functions of the human body (red for arteries/clean blood and

blue for veins/dirty blood etc.). Some displays literally have buttons in

the place of eyes with eyeballs painted on them, presumably to maintain

some sort of propriety and normality. Although this provoked quite the

opposite, rather unsettling reaction in my experience exactly the sort of

thing that the curators, perhaps wanted to avoid. I shall come back to the

aesthetic aspect later in the piece.

SECTION I

The whole notion of displaying the multifarious internal organs of the

human body, to be seen as objects of biological knowledge can be

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

contextualized in the backdrop of the rise of the discipline of biology itself,

shifting from the 18th century (and before) discipline of natural history to

the science of biology in the 19th century as described by Foucault

(1970). He points to Cuvier as the pivot around which the epistemological

transformation happens where the structure of knowledge of beings

changes from a flat, two-dimensional grid based on visible and outward

identities and differences to a centrifugal ordering and classification based

on identities and differences around an invisible and hidden notion of life.

This basically means that where previously, each organ was represented

in the grid of natural history on the basis of structure and function, that (in

its presentation) belied a certain independence or autonomous existence

of said organ within the larger body of the organism, and equal weightage

to both parameters; Cuvier subordinates the form, structure etc. of the

organ to the sovereignty of function whose aim becomes sustaining a

notion of life that is invisible to the naked eye (264).

From Cuvier onward, function, defined according to its nonperceptible form as an effect to be attained, is to serve as a

constant middle term and to make it possible to relate together

totalities of elements without the slightest visible identity. What to

Classical eyes were merely differences juxtaposed with identities

must now be ordered and conceived on the basis of a functional

homogeneity which is their hidden foundation (265).

The functional homogeneity is the larger functioning of the organism as a

whole, that introduces an interdependence and reciprocity of organs along

with an internal hierarchy according to their relative importance vis--vis

functions of the whole body. Thus for instance, within the digestive

system, the length, dilations and convolutions of the alimentary canal

become dependent on the form of the teeth. Also, the morphology of

limbs determines the type of food the organism will be able to tear and

capture and, accordingly ingest (265). Similarly, while gills and lungs may

not share any similarity with respect to form, magnitude or number, they

both serve the function of respiration, in general.

For Cuvier, the existence of the animal precedes the relationships

between its constituent parts, and they only interact to serve the purpose

of the former. There emerges a hierarchy of organs according to which the

various orders, classes, families et al. of animals are arranged, according

to a certain plan of nature. As a hierarchical principle, this plan defines

the most important functions, arranges the anatomical elements that

enable it to operate, and places them in the appropriate parts of the body

[] (267). Thus, the vital functions place their organs towards the centre

of the system and as we move outward toward the lesser organs, so to

speak, they become susceptible to other forms of determination fins are

equated with arms and so forth [] the species can at the same time resemble one another (so as

to form groups such as the genera, the classes, and what Cuvier

calls the sub-kingdoms) and be distinct from one another. What

draws them together is not a certain quantity of coincident

elements; it is a sort of focus of identity which cannot be analysed

into visible areas because it defines the reciprocal importance of the

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

various functions; on the basis of this imperceptible centre of

identities, the organs are arranged in the body, and the further they

are from the centre, the more they gain in flexibility, in the

possibilities of variation, and in distinctive characters. Animal

species differ at their peripheries, and resemble each other at their

centres; they are connected by the inaccessible, and separated by

the apparent (267).

Thus, the dark, invisible space - the great, mysterious, invisible focal

unity that one has to penetrate the surface of visibilities (only through

dissection) indicates the conditions of possibility for biology (269).

Concomitant with biology, comes the underlying teleological narrative that

breaks the continuity of time implicit with the natural history grid. It

presupposes a progression of life towards a telos, to the top of the

pyramid. A common example of this is the horshoe crab that is commonly

known as the living fossil (Sadava et al; 2009). This betrays a line of

thinking that would claim that despite its primitiveness, the horseshoe

crab survived into the modern epoch wherein only creatures of a certain

evolved state are able to adapt and ensure their survival. Whereas in the

classical taxonomy system it wouldve just fit into the flat grid, placed in a

box according to its features.

Thus, fragmented by life, that isolates forms that are bound in upon

themselves, the organs become representative of (and tending towards)

a normative ideal of a healthy and good life (Foucault, 273). This

underlying ideology informs the displays at the Anatomy Museum as well.

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

SECTION II

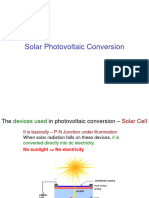

There are moreover, explicit visual markers such as mannequins of male

torsos above some of the glass shelves that definitively indicate a notion

of perfection in human health. The specimens are flexing their well-built

musculature and have networks of blue and red blood vessels, implying

peak physical condition. Additionally, there is graphic visual imagery in

the circulatory system section that shows, besides the blue-red schema

that is common throughout, blood travelling like forces of electricity

across the body (Figure 1 below).

Figure 1

While there are numerous displays of the ideal human body strategically

positioned around the place, they were paradoxically swarmed by the

innumerable other displays that illustrated how life can radically deviate

from the norm.

The first part of the answer to this phenomenon would be with reference

to the vast collection of fetuses on display. From premature still births to

aborted babies, there is an impressive spectrum on offer. Of special

significance are some of the taxonomical specificities, such as the

hydrocephalic monster - one among the many monsters that

showcases the still archaic residues of what was initially a discipline that

arose from encounters of European expansion with the rest of the world.

Franklin contextualizes the trajectory of the practice of collecting, storing

and displaying human and animal remains that, in the early modern

period, occupied the European aristocrat, that was not only intended to

educate but had the character of a frivolous pastime, intended to amuse

and titillate (Anker & Franklin, 104, 2011). So there is element of an

aestheticization of the exotic, horrific, the bizarre and monstrous in the

history of this practice. This purportedly changes however, with the

gradual emergence of natural history and then biology, when the practice

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

is absorbed into the serious pursuit of knowledge of the natural world

(104).

At the anatomy musuem however, the aesthetics of my encounter with

the specimens formed a significant part of the experience. The bright

lights, the sterile spick-and-span surroundings and the eerie interventions

on the specimens in the glass cases as well as the other visual cues

mentioned before, induce an inadvertent and unsettling reaction from the

spectator in the event of the unabashed presentation of grotesquerie. Part

of the motivation, evident especially in the pathology section that deals

with lifestyle diseases and their consequences on various organs of the

body, seems to come from a didactic, moral voice that seems to warn,

with its graphic accompaniments, against excesses of smoke, drink and

harmful foods.

CONCLUSION

The larger epistemological point of note here is that the incremental

mediation and intervention on the organic body in service of uncovering

the inner invisibilities driving biological life managed to counter-intuitively

widen the chasm between the representational modalities of knowledge

and the actual, living beings that are the purported objects of study

(Franklin, 104). Meaning that extracting and displaying, in a very specific

manner, the many parts (organs) that make up a single, whole human

body, and opening it up to unified human spectators results in a

significant reconfiguration of the relationships of the objects (parts)

between themselves and with the wholes. I sensed this myself, in the form

of a curiously alienating feeling being amidst that cornucopia of glass jars

filled with preserved dead organs, fetuses and cross-sectionals of animal

remains.

Concurrently, this ordering of objects betrays, as mentioned before, a

conception of an ideal of (human) life guiding the particular science of

biology. Consequently, this can become the grounds on which one could

begin questioning the discourse of biology and destabilising its positivist

claims to knowledge, by uncovering (in the Foucauldian sense) the

underlying and ever-changing ideological impulses driving this particular

discipline.

Bibliography

Anatomy Museum Overview. http://manipal.edu/kmc-manipal/kmcexperience/putting-manipal-on-the-map.html (accessed September

Sunday, 2015).

Anker, Suzanne, and Sarah Franklin. "Specimens as Spectacles Reframing

Fetal Remains." Social Text 29, no. 1 106 (2011): 103-125.

Sadava, David E., David M. Hillis, H. Craig Heller, and May Berenbaum.

Life: the science of biology. Vol. 2. Macmillan, 2009.

Body, Gender & Health #4

Anatomy Museum Report

Kartikeya Jain

Foucault, Michel. The order of things: An archaeology of the human

sciences. Vintage Books, 1994.

Você também pode gostar

- Form and Function: A Contribution to the History of Animal MorphologyNo EverandForm and Function: A Contribution to the History of Animal MorphologyAinda não há avaliações

- Form and Function A Contribution to the History of Animal MorphologyNo EverandForm and Function A Contribution to the History of Animal MorphologyAinda não há avaliações

- Cuvier Según Foucault y Los EECCDocumento14 páginasCuvier Según Foucault y Los EECCFran GelmanAinda não há avaliações

- Archaeology of The BodyDocumento21 páginasArchaeology of The Bodyledzep329Ainda não há avaliações

- Man, Creation and The Fossil RecordDocumento6 páginasMan, Creation and The Fossil RecordTim StickAinda não há avaliações

- 30-Second Anatomy: The 50 most important structures and systems in the human body each explained in under half a minuteNo Everand30-Second Anatomy: The 50 most important structures and systems in the human body each explained in under half a minuteNota: 2.5 de 5 estrelas2.5/5 (2)

- The Ethiric BodyDocumento18 páginasThe Ethiric BodyKakz KarthikAinda não há avaliações

- A Treatise on Physiology and Hygiene: For Educational Institutions and General ReadersNo EverandA Treatise on Physiology and Hygiene: For Educational Institutions and General ReadersAinda não há avaliações

- Teleology - Yesterday, Today, and TomorrowDocumento20 páginasTeleology - Yesterday, Today, and TomorrowLetícia LabatiAinda não há avaliações

- Dry Bones: Exposing The History And Anatomy of Bones From Ancient TimesNo EverandDry Bones: Exposing The History And Anatomy of Bones From Ancient TimesAinda não há avaliações

- Dwarfs in Athens PDFDocumento17 páginasDwarfs in Athens PDFMedeiaAinda não há avaliações

- EVOLUTIONDocumento15 páginasEVOLUTIONKiama GitahiAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence For Human EvolutionDocumento6 páginasEvidence For Human EvolutionThanh Khuê LêAinda não há avaliações

- Origin of Life On Earth. Getty/Oliver BurstonDocumento15 páginasOrigin of Life On Earth. Getty/Oliver BurstonRaquel Elardo AlotaAinda não há avaliações

- Half Hours With Modern Scientists: Lectures and EssaysNo EverandHalf Hours With Modern Scientists: Lectures and EssaysAinda não há avaliações

- Cells to Civilizations: The Principles of Change That Shape LifeNo EverandCells to Civilizations: The Principles of Change That Shape LifeNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (4)

- Teleology Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow by Michael RuseDocumento20 páginasTeleology Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow by Michael RuseTrust IssuesAinda não há avaliações

- The Sacred Body: Materializing the Divine through Human Remains in AntiquityNo EverandThe Sacred Body: Materializing the Divine through Human Remains in AntiquityNicola LaneriAinda não há avaliações

- Volume 11. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Energy and biological mechanisms of refocusings of Self-Consciousness»No EverandVolume 11. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Energy and biological mechanisms of refocusings of Self-Consciousness»Ainda não há avaliações

- Zelfstudie Van Blastula Naar 3 KiemlagenDocumento18 páginasZelfstudie Van Blastula Naar 3 KiemlagenCheyenne ProvoostAinda não há avaliações

- GOD and Quantum Physics PDFDocumento19 páginasGOD and Quantum Physics PDFsamu2-4uAinda não há avaliações

- Cia As2Documento10 páginasCia As2Ned TinneAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence of Evolution FinalDocumento82 páginasEvidence of Evolution FinalCheskaAinda não há avaliações

- Form and FunctionA Contribution To The History of Animal Morphology by E. S. (Edward Stuart) RussellDocumento246 páginasForm and FunctionA Contribution To The History of Animal Morphology by E. S. (Edward Stuart) RussellGutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Evidence: Ch. 2 Tiktaalik/ The Rotation of Our Knees and Elbows in UteroDocumento13 páginasThe Evidence: Ch. 2 Tiktaalik/ The Rotation of Our Knees and Elbows in UteroCory LukerAinda não há avaliações

- Science LayoutDocumento2 páginasScience LayoutGillian OpolentisimaAinda não há avaliações

- Joyce Archeology of The BodyDocumento22 páginasJoyce Archeology of The Bodywhatev_broAinda não há avaliações

- 64299-Texto Del Artículo-370264-1-10-20180130Documento51 páginas64299-Texto Del Artículo-370264-1-10-20180130Yazmin GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Science of Medicine: by Aaron C. Ericsson, DVM, PHD, Marcus J. Crim, DVM & Craig L. Franklin, DVM, PHDDocumento5 páginasScience of Medicine: by Aaron C. Ericsson, DVM, PHD, Marcus J. Crim, DVM & Craig L. Franklin, DVM, PHD苏嘉怡Ainda não há avaliações

- The Tree of Life: An Interdisciplinary Journey from Mythology to ScienceNo EverandThe Tree of Life: An Interdisciplinary Journey from Mythology to ScienceAinda não há avaliações

- Bed 130 - Week 1 TaskDocumento27 páginasBed 130 - Week 1 TaskPaul Ivan L. PazAinda não há avaliações

- Worksheet Q3 Week 5Documento2 páginasWorksheet Q3 Week 5Jaybie TejadaAinda não há avaliações

- Cognition and Semiotic Processing of Luminous Stimuli in Various Orders of The Natural WorldDocumento12 páginasCognition and Semiotic Processing of Luminous Stimuli in Various Orders of The Natural WorldJose Luis CaivanoAinda não há avaliações

- Notes on Veterinary Anatomy: (Illustrated Edition)No EverandNotes on Veterinary Anatomy: (Illustrated Edition)Ainda não há avaliações

- Clitoral ConventionsDocumento49 páginasClitoral ConventionsLeonardo ZanniniAinda não há avaliações

- Unraveling the Secrets of Humanity: A Journey through Time, Science, and WonderNo EverandUnraveling the Secrets of Humanity: A Journey through Time, Science, and WonderAinda não há avaliações

- (2005) Archaeology of The Body (Joyce)Documento25 páginas(2005) Archaeology of The Body (Joyce)Nathaly Kate BohulanoAinda não há avaliações

- Geller 2009 BodyscapesDocumento13 páginasGeller 2009 BodyscapesPaz RamírezAinda não há avaliações

- Evidences of Evolution Module 6-7Documento47 páginasEvidences of Evolution Module 6-7GLAIZA CALVARIOAinda não há avaliações

- Stross SacrumDocumento54 páginasStross SacrumbstrossAinda não há avaliações

- Discovering the Human: Life Science and the Arts in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth CenturiesNo EverandDiscovering the Human: Life Science and the Arts in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth CenturiesRalf HaekelAinda não há avaliações

- Bodies On DisplayDocumento12 páginasBodies On DisplaybbjanzAinda não há avaliações

- Origins of Life: A D D S C DDocumento23 páginasOrigins of Life: A D D S C DjonasgoAinda não há avaliações

- AnatomyDocumento16 páginasAnatomywakhalewakhaleAinda não há avaliações

- Hypercell 1994 Engl by Hans HassDocumento126 páginasHypercell 1994 Engl by Hans HassClaimDestinyAinda não há avaliações

- Fossils Disprove Evolution'j: Nonethelessml Mke An Agrravating Thing To Havr To ExplainDocumento4 páginasFossils Disprove Evolution'j: Nonethelessml Mke An Agrravating Thing To Havr To ExplainRodz TennysonAinda não há avaliações

- The Specimen Mysteries From The Fossil HDocumento157 páginasThe Specimen Mysteries From The Fossil HJose Perez LopezAinda não há avaliações

- The Organ of Form: Towards A Theory of Biological ShapeDocumento11 páginasThe Organ of Form: Towards A Theory of Biological Shapesusanne voraAinda não há avaliações

- Yif Responses - Rachel Reading QsDocumento10 páginasYif Responses - Rachel Reading Qsapi-436795607Ainda não há avaliações

- Evolution DBQDocumento4 páginasEvolution DBQCharles JordanAinda não há avaliações

- Week 1 - Relevance, Mechanisms, Evidence/Bases, and Theories of EvolutionDocumento5 páginasWeek 1 - Relevance, Mechanisms, Evidence/Bases, and Theories of EvolutionDharyn Khai100% (2)

- Anthropology Course Code: Anth101 Credit Hours: 3Documento25 páginasAnthropology Course Code: Anth101 Credit Hours: 3Tsegaye YalewAinda não há avaliações

- Life, Not Itself: Inanimacy and The Limits of Biology: Please ShareDocumento27 páginasLife, Not Itself: Inanimacy and The Limits of Biology: Please ShareaverroysAinda não há avaliações

- Evolutia FotoreceptorilorDocumento147 páginasEvolutia FotoreceptorilorAnca MihalcescuAinda não há avaliações

- Medrano, Rene LynnDocumento2 páginasMedrano, Rene LynnRene Lynn Labing-isa Malik-MedranoAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 7 ActivitiesDocumento8 páginasUnit 7 ActivitiesleongeladoAinda não há avaliações

- SD-NOC-MAR-202 - Rev00 Transfer of Personnel at Offshore FacilitiesDocumento33 páginasSD-NOC-MAR-202 - Rev00 Transfer of Personnel at Offshore Facilitiestho03103261100% (1)

- College of Engineering Cagayan State UniversityDocumento16 páginasCollege of Engineering Cagayan State UniversityErika Antonio GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- IES OBJ Civil Engineering 2000 Paper IDocumento17 páginasIES OBJ Civil Engineering 2000 Paper Itom stuartAinda não há avaliações

- Code of Federal RegulationsDocumento14 páginasCode of Federal RegulationsdiwolfieAinda não há avaliações

- Research Project Presentation of Jobairul Karim ArmanDocumento17 páginasResearch Project Presentation of Jobairul Karim ArmanJobairul Karim ArmanAinda não há avaliações

- تأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFDocumento36 páginasتأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFSofiane DouifiAinda não há avaliações

- Bilateral Transfer of LearningDocumento18 páginasBilateral Transfer of Learningts2200419Ainda não há avaliações

- Group 4 - When Technology and Humanity CrossDocumento32 páginasGroup 4 - When Technology and Humanity CrossJaen NajarAinda não há avaliações

- Naca Duct RMDocumento47 páginasNaca Duct RMGaurav GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Piaggio MP3 300 Ibrido LT MY 2010 (En)Documento412 páginasPiaggio MP3 300 Ibrido LT MY 2010 (En)Manualles100% (3)

- Paper Ed Mid TermDocumento2 páginasPaper Ed Mid Termarun7sharma78Ainda não há avaliações

- Slide 7 PV NewDocumento74 páginasSlide 7 PV NewPriyanshu AgrawalAinda não há avaliações

- CS3501 Compiler Design Lab ManualDocumento43 páginasCS3501 Compiler Design Lab ManualMANIMEKALAIAinda não há avaliações

- Schmidt Hammer TestDocumento5 páginasSchmidt Hammer Testchrtrom100% (1)

- Corrosion Protection PT Tosanda Dwi SapurwaDocumento18 páginasCorrosion Protection PT Tosanda Dwi SapurwaYoga FirmansyahAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation MA History PeterRyanDocumento52 páginasDissertation MA History PeterRyaneAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1 - Plant & Eqpt. Safety Apprisal & Control Techq.Documento147 páginasUnit 1 - Plant & Eqpt. Safety Apprisal & Control Techq.Madhan MAinda não há avaliações

- Problems: C D y XDocumento7 páginasProblems: C D y XBanana QAinda não há avaliações

- Admission: North South University (NSU) Question Bank Summer 2019Documento10 páginasAdmission: North South University (NSU) Question Bank Summer 2019Mahmoud Hasan100% (7)

- 2018-2019 Annual Algebra Course 1 Contest: InstructionsDocumento2 páginas2018-2019 Annual Algebra Course 1 Contest: InstructionsNaresh100% (1)

- Filling The Propylene Gap On Purpose TechnologiesDocumento12 páginasFilling The Propylene Gap On Purpose Technologiesvajidqc100% (1)

- SQL and Hand BookDocumento4 páginasSQL and Hand BookNaveen VuppalaAinda não há avaliações

- World English 2ed 1 WorkbookDocumento80 páginasWorld English 2ed 1 WorkbookMatheus EdneiAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Two: General Design ConsiderationsDocumento27 páginasChapter Two: General Design ConsiderationsTeddy Ekubay GAinda não há avaliações

- Aectp 300 3Documento284 páginasAectp 300 3AlexAinda não há avaliações

- Natal Chart Report PDFDocumento17 páginasNatal Chart Report PDFAnastasiaAinda não há avaliações

- Dayco-Timing Belt Training - Entrenamiento Correa DentadaDocumento9 páginasDayco-Timing Belt Training - Entrenamiento Correa DentadaDeiby CeleminAinda não há avaliações

- Romano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)Documento7 páginasRomano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)ទី ទីAinda não há avaliações