Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Do Brain Interventions To Treat Disease Change The Essence of Who We Are?

Enviado por

Matteo Cardillo0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

5 visualizações4 páginasDo Brain Interventions To Treat Disease Change The Essence Of Who We Are?

Título original

Do Brain Interventions to Treat Disease Change the Essence of Who We Are?

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

RTF, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDo Brain Interventions To Treat Disease Change The Essence Of Who We Are?

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato RTF, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

5 visualizações4 páginasDo Brain Interventions To Treat Disease Change The Essence of Who We Are?

Enviado por

Matteo CardilloDo Brain Interventions To Treat Disease Change The Essence Of Who We Are?

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato RTF, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 4

Do Brain Interventions To Treat

Disease Change The Essence

Of Who We Are?

These days, most of us accept that minds are dependent on

brain function and wouldnt object to the claim that You are

your brain. After all, weve known for a long time thatbrains

control how we behave, what we remember, even what we

desire. But what does that mean? And is it really true?

Despite giving lip service to the importance of brains, in our

practical life this knowledge has done little to affect how we

view our world. In part, thats probably because weve been

largely powerless to affect the way that brains work, at least in

a systematic way.

Thats all changing. Neuroscience has been advancing rapidly,

and has begun to elucidate the circuits for control of behavior,

representation of mental content and so on. More dramatically,

neuroscientists have now started to develop novel methods of

intervening in brain function.

As treatments advance, interventions into brain function will

dramatically illustrate the dependence of who we are on our

brains and they may put pressure on some basic beliefs and

concepts that have been fundamental to how we view the

world.

Pacemaker For Heart Versus One For The Brain

Medicine has long intervened in the human body. We are

comfortable and familiar with the reality of implants that keep

the heart going at a steady and even pace. We dont think

pacemakers threaten who we are, nor that they raise deep and

puzzling ethical questions about whether such interventions

should be permissible. The brain, like the heart, is a bodily

organ, but because of its unique function, its manipulation

carries with it a host of ethical and metaphysical conundrums

that challenge our intuitive and largely settled views about who

and what we are.

The last few decades have seen a variety of novel brain

interventions. Perhaps the most familiar is the systemic

alteration of brain chemistry (and thus function) by a growing

array of psychopharmaceuticals. However, more targeted

methods of intervening exist, including direct or transcranial

electrical stimulation of cortex, magnetic induction of electrical

activity, and focal stimulation of deep brain structures.

Still on the horizon are even more powerful techniques not yet

adapted or approved for use in humans. Transgenic

manipulations that make neural tissue sensitive to light will

enable the precise control of individual neurons. Powerful gene

editing techniques may enable us to correct some

neurodevelopmental problems in utero. And although many of

these methods seem futuristic, hundreds of thousands of cases

of the future are already here: over 100,000 cyborgs are

already walking among us, in some sense powered by or

controlled by the steady zapping of their brain circuits with

electrical pulses.

This is no dystopian nightmare, nor the idea for a new zombie

show. Deep brain stimulation (or DBS) has been a life-restoring

therapeutic technique for thousands of patients with

Parkinsons disease with severely impaired motor and cognitive

function, and it promises to dramatically improve the lives of

people suffering from some other psychological and

neurological disorders, including obsessive compulsive disorder,

treatment-resistant depression, and Tourettes syndrome.

DBS involves the placement of electrodes into deep brain

structures. Current is administered through these electrodes by

an implanted power pack, which can be remotely controlled by

the subject and adjusted by physicians. In essence, DBS is like

a pacemaker for the brain.

Remarkably, we dont quite know how it works, but when

effective, DBS can in seconds restore normal function to a

person virtually paralyzed by a dopamine deficiency, contorted

by uncontrollable tremor and muscular contraction. The

transformation is nothing short of miraculous.

When Neuroscience Answers Push Us Toward Philosophy

Questions

In addition to its obvious clinical benefits, DBS poses some

interesting problems.

For one thing, DBS does not always only address the troubling

symptoms of the disease it aims to treat. Sometimes,

stimulation results in unanticipated side-effects, altering mood,

preferences, desires, emotion or cognition. In one reported

case, the identifiable side effect of stimulation was a sudden

and unprecedented obsession with Johnny Cashs music.

While it may be fairly easy to write off improvements in motor

control as some kind of mechanical restoration of a broken

output circuit (which would be a misunderstanding of the actual

function of DBS in Parkinsons), messing with our preferences

and passions seems to hit much closer to home. It calls

attention to something hard to fathom and often overlooked:

what we like, what we are like, who we are, in some very real

sense, are dependent on the motion of matter and ebb and flow

of electrical signals in our brains, just like any other physical

devices.

This reminder points to something we may often pay lip service

to, without really coming face to face with its implications.

However, the increasing availability of neurotechnologies may

push us to deeper philosophical exploration of the truth about

our brains and our selves.

After all, if we are merely material beings whose personality

can be altered and even controlled by fairly simple

technologies, is there really a there there? Is there some

immutable kernel of a person that is the self, or an essence that

resists change? Can brain interventions can change who we are

make us into a different person or alter personal identity?

If someone insults you (or commits a crime) while under

stimulation by DBS, should he be held responsible for what he

does? Under what conditions (if any) does it make sense to say

that it wasnt really him? Does the answer give us insight into

what matters about brain function? And if we think that brain

interventions should excuse people, when and why is that so?

Does that reasoning also imply that we ought to excuse all

behavior due to brains, which are, after all, just physical

systems operating according to natural laws? That is, does it

threaten to undermine the notion of responsibility more

generally?

These are hard questions that philosophers have been

grappling with for a long time. For the most part they were

relegated to the academy and the realm of thought

experiments, and were largely ignored by the rest of the world.

But we live today in a world of thought experiment made real,

and these questions are now being raised in practical

circumstances in medicine and in law. Although there is no

consensus (and I do not mean to endorse what might seem to

be the obvious answers to the above questions), what have

previously seemed like the abstract puzzles of philosophers

may soon be seen to hit closer to home.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Active ListeningDocumento2 páginasActive ListeningMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Reichian Therapy The Technique For Home UseDocumento542 páginasReichian Therapy The Technique For Home UseThomas Scott JonesAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- 661 - Buffy The Musical Theme - Once More, With FeelingDocumento1 página661 - Buffy The Musical Theme - Once More, With FeelingMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Michael Nyman - The Piano (v2) (Sheet Music)Documento4 páginasMichael Nyman - The Piano (v2) (Sheet Music)MissChiefingAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Calibre SdfdsasdfbookfdsasdfmarksDocumento1 páginaCalibre SdfdsasdfbookfdsasdfmarksMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- 677 - Kate Winslet - What IfDocumento2 páginas677 - Kate Winslet - What IfPattyCowAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Calibre SdfdsasdfbookmarksDocumento1 páginaCalibre SdfdsasdfbookmarksMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Levels of Existence and Hierarchy of Needs Compared: Graves & MaslowDocumento6 páginasLevels of Existence and Hierarchy of Needs Compared: Graves & MaslowMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- 618 - Kathy Fisher - I Will Love You PDFDocumento3 páginas618 - Kathy Fisher - I Will Love You PDFBilson BillsAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- 14 YearsDocumento4 páginas14 YearsChristie K. ChowAinda não há avaliações

- Various CeoDocumento1 páginaVarious CeoMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- LENNY KRAVITZ - It Ain't Over 'Till Is OverDocumento2 páginasLENNY KRAVITZ - It Ain't Over 'Till Is Overpianomen23Ainda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- AsdfghjkjgDocumento1 páginaAsdfghjkjgMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- FghjfruytrfDocumento1 páginaFghjfruytrfMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Science of Vocal Bridges, Part VDocumento116 páginasThe Science of Vocal Bridges, Part VMatteo Cardillo50% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Muse - The 2nd LawDocumento3 páginasMuse - The 2nd LawMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Science of Vocal Bridges Part IDocumento35 páginasThe Science of Vocal Bridges Part IRichardDeanAndersonAinda não há avaliações

- Stress Harms Infants' Learning FlexibilityDocumento1 páginaStress Harms Infants' Learning FlexibilityMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- IntroDocumento15 páginasIntroMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- MotionDocumento23 páginasMotionMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- MotionDocumento23 páginasMotionMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- EditingDocumento28 páginasEditingMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- Frost o CombDocumento1 páginaFrost o CombMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- TermDocumento15 páginasTermMatteo CardilloAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Waves System GuideDocumento6 páginasWaves System GuideChris FunkAinda não há avaliações

- Chap008 DetailedDocumento38 páginasChap008 Detailedplato986Ainda não há avaliações

- MSF SFT Practitioner Resource Guide VOL 1Documento69 páginasMSF SFT Practitioner Resource Guide VOL 1Nor KarnoAinda não há avaliações

- Perdev Test Q2 Solo FrameworkDocumento5 páginasPerdev Test Q2 Solo Frameworkanna paulaAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- NCP-Imbalanced Nutrition Less Than Body RequirementsDocumento2 páginasNCP-Imbalanced Nutrition Less Than Body RequirementsJon Eric G. Co84% (37)

- 10 - Conflict ManagementDocumento13 páginas10 - Conflict ManagementChristopher KipsangAinda não há avaliações

- Health 7 Q3 M4Documento18 páginasHealth 7 Q3 M4edel dearce IIIAinda não há avaliações

- A Study On The Importance of Cross Cultural Training For Employees of Various OrganizationsDocumento11 páginasA Study On The Importance of Cross Cultural Training For Employees of Various OrganizationsanitikaAinda não há avaliações

- Eds3701 Assignment 1Documento7 páginasEds3701 Assignment 1mangalamacdonaldAinda não há avaliações

- أسس اللسانيات العرفانية، المنطلقات والاتجاهات المعاصرة The FoundationsDocumento11 páginasأسس اللسانيات العرفانية، المنطلقات والاتجاهات المعاصرة The FoundationscchabiraAinda não há avaliações

- Adverse Effects of Gadgets On KidsDocumento1 páginaAdverse Effects of Gadgets On Kidsnicole bejasaAinda não há avaliações

- Report Card CommentsDocumento4 páginasReport Card CommentsJumana MasterAinda não há avaliações

- Exam Paper For People Strategy in Context: (CPBDO1001E)Documento17 páginasExam Paper For People Strategy in Context: (CPBDO1001E)Christine HarditAinda não há avaliações

- Libro Anorexia NerviosaDocumento12 páginasLibro Anorexia NerviosaSara VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-2Documento9 páginasReynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-2api-489450491Ainda não há avaliações

- The Relationship Between Communication Competence and Organizational ConflictDocumento22 páginasThe Relationship Between Communication Competence and Organizational ConflictIulian MartAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence Claim Assessment WorksheetDocumento3 páginasEvidence Claim Assessment WorksheetYao Chong ChowAinda não há avaliações

- Operant ConditioningDocumento14 páginasOperant Conditioningniks2409Ainda não há avaliações

- H5MG04Documento11 páginasH5MG04Dreana MarshallAinda não há avaliações

- Conceptualization of Planned ChangeDocumento4 páginasConceptualization of Planned ChangeAnisAinda não há avaliações

- Compassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipDocumento14 páginasCompassionate Love As Cornerstone of Servant LeadershipAnthony PerdueAinda não há avaliações

- Group 4:: Responsibility AS ProfessionalsDocumento20 páginasGroup 4:: Responsibility AS ProfessionalsMarchRodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Distracted From Center - PicsDocumento5 páginasDistracted From Center - PicsTina WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 Quiz KeyDocumento6 páginasChapter 4 Quiz Keyv9pratapAinda não há avaliações

- Stuvia 521677 Summary Strategy An International Perspective Bob de Wit 6th Edition PDFDocumento86 páginasStuvia 521677 Summary Strategy An International Perspective Bob de Wit 6th Edition PDFRoman BurbakhAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership Training For ManagersDocumento3 páginasLeadership Training For ManagersHR All V ConnectAinda não há avaliações

- Crim Soc 3Documento40 páginasCrim Soc 3noronisa talusobAinda não há avaliações

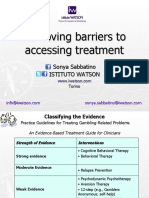

- Eacbt Sabbatino Mi 2010Documento18 páginasEacbt Sabbatino Mi 2010Sonya SabbatinoAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding The Nature and Scope of Human Resource ManagementDocumento38 páginasUnderstanding The Nature and Scope of Human Resource ManagementNiharika MathurAinda não há avaliações

- Laws and TheoriesDocumento20 páginasLaws and TheoriesMK BarrientosAinda não há avaliações

- LA019636 Off The Job Assessment Nurture ClusterDocumento19 páginasLA019636 Off The Job Assessment Nurture ClusterReda SubassAinda não há avaliações

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNo EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (13)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeAinda não há avaliações

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNo EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)