Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Weapon Against Waste

Enviado por

Mohamed Farag MostafaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Weapon Against Waste

Enviado por

Mohamed Farag MostafaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Lean Six Sigma

Weapon Against Waste

Lean Six Sigma

implementation in

the U.s. Army

ean Six Sigma (LSS), as the name suggests, is a combination of lean

production and Six Sigma methods. And its a program the U.S. Army

has adopted as its weapon of choice for fighting off process inefficiencies

that result in wasted time, money and material.

LSS enables organizations to simultaneously do business faster (time reduction) and better (defect reduction) by improving the mean of the process

performance while also reducing the process variation.1

Many firms, including the Army Office of Business Transformation (OBT), 2

have realized the potential of LSS as the most effective approach to business

improvement. Since its implementation throughout the Armys manufacturing

depots and logistical units, LSS has resulted in highly successful improvement

transformations.3 LSS provided the Army with the tools it needed to meet its

transformation goals, and the Army provided the grounds for unleashing

LSSs great potential.

Military mission

By Jonas A.

Guintivano,

U.S. Army,

and M. Hosein

Fallah, University

of Maryland

University College

To better understand the rationale behind LSS and its implementation by the

Army, it is important to understand what the Armys mission is and how it differs

from other organizations.

Unlike the private sector, the military is not driven by profit. The Armys

unique mission is to defend the United States and its Constitution; preserve the peace and security, and defend the United States, its territories,

Commonwealths and possessions; support national policies; and overcome

any nations responsible for aggressive acts that imperil the peace and security

of the United States.4

The Armys operations are funded by the government via taxpayer dollars,

and its manpower is supported by Department of Defense (DoD) civilian

personnel and typical business transactions pertaining to Army missions. In

other words, the Armys bottom line is combat readiness, and its customers

and clients are U.S. citizens.

As the Armys mission continually adapts to world politics and objectives set

by the National Security Council, so has its manpower and funding. During

the Cold War, the Army had an average of 547,000 soldiers serving at home in

the United States and at forward operating bases such as Germany and Italy.

The transformation of the Armys forces began in the 1990s as the Cold War

ended. Traditional operation forces were downsized as more agile operational

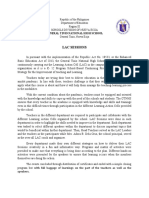

forces were taking shape.5 As depicted in Figure 1 (p. 10), the strength of Army

forces has changed considerably during the last half-century.

Currently, the Army has about 498,000 soldiers and is more flexible when

responding to worldwide conflicts, humanitarian efforts, and peacekeeping

missions at home and abroad.6 The change in manpower has not affected

six sigma forum magazine

february 2012

Weapon Aga in st Was t e

operations during the current era of conflicts in the

Middle East; the Army has fought two wars while

operating at a high operations tempo.

The major challenges facing the Army today are

supporting an uncertain political environment,

changing resource conditions and sustaining current

garrison operations. The objectives of the Armys new

organizational design have been mitigating near-term

risk and restoring balance to the current and future

demands of the Army.

In Executive Order (EO) 13450, dated Nov. 13,

2007, President George W. Bush required all government agencies to become better stewards of U.S. taxpayer dollars.7 The Army selected the implementation

of LSS practices as a course of action to achieve its

dynamic mission while using current resources more

efficiently. But it couldnt have done it without four

factors that sets the Army apart from other organizations:

1. Leadership

In the military, a chain of command exists to ensure

direction, guidance and adherence to protocol. The

execution of efforts is aligned with the person or

agency for which the subordinate is responsible.

This tiered and aligned decision-making structure

will always refer to the support of senior Army leadership, whose architecture is essential to ensuring all

missions are strategically planned in a top-to-bottom

manner. This allows for the execution to occur at all

levels of the chain and is crucial for several reasons.

As described in the Army Lean Six Sigma Deployment

Guidebook, leadership leverages executive talent and

capability involving all of the Armys most senior insti-

Figure 1. Soldiers serving in the U.S. Army

700,000

600,000

500,000

642,820

589,431

519,233

545,992

400,000

498,000

449,563

387,467

300,000

200,000

100,000

0

10

1957 1967 1977 1987 1997 2007 2010

february 2012

W W W . AS Q . ORG

tutional leaders in advising the Secretary of the Army

and the Army Secretariat.8

Leadership also establishes transparency throughout the chain of command to ensure all relevant

perspectives are considered and well-coordinated

while courses of actions are vetted and implemented.

In addition, it assigns accountability throughout the

decision-making processes and encourages proper

decision making at all levels.

Clearly defined roles and responsibilities are published in the LSS guidebook to ensure personnel

involved with LSS processes understand its objectives, roles and responsibilities, and that these operating procedures are standardized throughout the

Army.

The enterprise concept is the Armys approach to

institutional adaptation of the LSS program. At the

top of the chain are the Secretary of the Army and the

Army Secretariat. Following instruction from the top,

the Army enterprise concept has three tiers of hierarchy (see Figure 2). At the top is the Army Enterprise

Board (AEB), which is comprised of senior, strategiclevel advising bodies in the Department of the Army.

They are responsible for framing courses of action to

support the Secretary of the Army and to ensure decisions made that will affect the Army enterprisewide

are discussed prior to implementation.

Within the AEB is a panel of LSS experts that advise

the board on current LSS issues, along with another

supporting tier, the Headquarters, Department of

the Army (HQDA), which identifies opportunities for

streamlined and improved policy development and

implementation.

The HQDA ensures continued compliance with

laws, directives, regulations and orders while LSS

testing and implementation occur. The strategic

direction of the AEB is carried out by the chief

management officer (CMO). The OBTs activities

are integral in enabling the CMO to bridge policy

and execution gaps. The LSS program directorate

is within the OBT.

Finally, there are four core enterprises (CE) that

identify, prioritize and raise strategic issues in existing HQDA or AEB forums. The leaders of these CEs

manage Army-wide priorities in their respective

functional departments but align their functions,

processes and working relationships across all areas.

The hierarchy of the Armys LSS leadership is

important because many of the critical decisions

madesuch as whether to employ LSSoccur at the

top; but execution of these decisions typically occurs

W e a p o n Ag a i n st W as t e

Army

Enterprise

Board

Figure 2. U.S. Armys enterprise concept

Secretary of

the Army

General Counsel

(including LSS experts)

HQDA (including various

Army Commands)

Army

Management

Enterprise

Strategic

Direction

Chief Management Officer

Director, Office of Business Transformation

Transformation

Directorate

Operations

Directorate

Assessment

Directorate

Approve/

endorse

Core

enterprise

at the tactical levelor unit levelof the military, so

information must be disseminated throughout the

organization to encourage shared knowledge and

practices.

As previously mentioned, the enterprise concept

is the Armys approach to institutional adaptation.

It ensures the Army operates in a spirit of collaboration, synchronization and transparency. The defined

roles and responsibilities pertain to the chain of command as specific personnel are assigned the duties of

LSS implementation and management. These roles,

responsibilities and processes established by the LSS

guidebook help the Army think, act and operate as a

single enterprise.

This guidebook is similar to other standard operating procedures that exist within the Army to ensure

standardization of daily operating practices for specifically assigned duties. If at any point there is deviation from the roles and responsibilities, the chain

of command will be involved, and corrective actions

will occur.

The Army has a well-established formal training

program for LSS. The program offers training for

all Six Sigma belts:

White Belt training is offered to expose a critical

mass of its workforce to the power of LSS.

Yellow Belts are trained to maintain a general

knowledge of LSS and help identify processes in

their organization that need improvement.

Green Belts (GBs) are expected to apply LSS

to their daily work environments by driving

improvements in their facility, department or

workgroup.

Black Belts (BBs) work on large-scale and crossorganizational process improvements.

Master Black Belts (MBBs) coach and mentor

GBs and BBs while guiding multiple LSS projects. They are also expected to teach and facilitate LSS training.

Executive or project sponsors own the processes

GB and BB projects work to improve. Project

sponsors assign belts to a project, help write project charters and push projects forward. They are

critical to the Armys LSS success.9

The Armys LSS program has trained more than

1,450 senior leaders and has completed nearly 5,200

projects. More than 1,900 projects are currently in

progress. The completed projects have resulted in

significant financial and operational benefits across

the Army. Since 2009, it has submitted projects worth

a combined savings of $96.6 million to support

Readiness

Management

Support Office

Submit

Human

capital

Material

Services and

infrastructure

HQDA = Headquarters, Department of the Army

President Barack Obamas goal of $100 million in

savings throughout the government.10

2. Culture

The culture of the Army is rooted in tradition and

customs, and is subject to adherence of federal, DoD

and Army policies. Implementation and management

of continuous improvement processes and LSS were

mandated in DoD Instruction No. 5010.43, which was

a response to EO 13450.11

When the Army established its program in 2006,

only a few enthusiastic and knowledgeable professionals in the Army knew about LSS and how to

employ its tactics in a military environment. And,

as with any type of change, there was bound to be

resistance.

Knowing that a new way of doing business will be

met with reluctance is why leaders at all levels need

to embrace enterprise thinking and adopt a mindset

of doing whats good for the Army, good for the DoD

and good for the nation. As more people become

aware of LSS implementation, the acceptance and

willingness to change will follow.

The LSS guidebook recommends that strategic

leaders be involved in circulating communication

about the Army enterprise, mindset and LSS program.12 Every rank from general to private should

six sigma forum magazine

february 2012

11

Weapon Aga in st Was t e

understand this program, its terminology and desired

outcomes. Project sponsorship at all levels will engage

the troops to come up with innovative ideas to drive

efficiency and save taxpayer dollars.

It should be noted that the majority of personnel exposed to LSS training and LSS projects have

been in the logistics, IT and acquisition fields. In

the DoD and Army, these personnel include officers

and senior DoD civilians. Although they inherently

embody the Army and military culture, they operate

in an enterprise environment. Currently, its not clear

how LSS implementation can be extended to the field

operationsor whether it can at all.

3. Commitment

The Army is committed to ensuring a fault-proof

deployment strategy for the successful implementation of LSS. Beginning in 2006, the Army launched

its LSS efforts toward achieving business transformation. In 2007, the Army achieved breakthroughs as

it continued to build momentum with the program.

By 2008, the plan was to accelerate these changes

and LSS implementation across the Army. In 2009,

the Army built upon self-sustainment to institutionalize implementation across the organization. In 2010,

the goal was to achieve a steady state to maintain

institutionalization in the Army.

4. Community of practice

Other reasons for the Armys success include availability of data and information. The Army is the leader

in the service groups for LSS implementation and has

established a website that highlights community practices, reduces redundancy and benchmarks operations

organizationwide within different services. In April

2009, the Army launched the OBT as mandated by

Congress and in accordance with General Order No.

2010-01.13

The OBT enables the Army to institutionalize business transformation, including cultural change, and

supports Army leadership with the resources, skills

and commitment to adjust the way the Army does

business and dramatically improve Army business

operations.14

Case studies

At the Anniston Army Depot in Alabama, successful

LSS implementation resulted in processes that are

more cost effective and less demanding in terms of

12

february 2012

W W W . AS Q . ORG

man-hours. The depots bottom line is to continually

process high-quality products on time and within constraints of the budget so equipment can be returned

to the warfighter quickly at the lowest possible cost to

the taxpayers.15

Due to the current state of war, the depot needs to

support a higher demand in workload for receiving

and returning equipment to warfighters. The depots

workload increased from 4 million direct labor hours

in 2004 to 6.3 million hours in 2006.16

One of the most successful cases of LSS implementation is the improvement of the Army Depots M1

Abrams tank assembly line. Prior to LSS implementation, each employee assembled an entire module of

the M1 from start to finish in typical vehicle maintenance bay style, in which workers are assigned to

and focused on the equipment theyre working on.

After analyzing, organizing and reviewing operations, the Anniston Army Depot determined that

a one-piece flow operation could reduce assembly

time by 2.2 man-hours for each module and staffing

requirements from five to four workers. Those successful efforts resulted in a reduction throughput

time of 56%from 4.5 days to two days.17

After workers at the depot saw how valuable LSS

implementation was to that particular process, other

workers began reviewing operations in their areas

and analyzed ways to improve performance.

The M2 machine-gun assembly line eliminated

waste and transformed work cells to a continuous,

one-piece flow system, thus reducing assembly time of

the weapon from 2.5 man hours to one and staffing

from 18 to 15. As a result, production increased from

50 to more than 100 machine guns per month.18

The most significant finding was that prior to LSS

implementation, mechanics spent significant time

chasing down parts. Now, with their improved workstations, the mechanics are able to focus on doing

their job and assembling or fixing equipment.19

Other LSS stories published in the Defense

Acquisition, Technology and Logistics journal documented successes across different agencies in the Army. In

2006, the Red River Army Depot in Texarkana, TX,

saved $30 million on its High Mobility Multipurpose

Wheeled Vehicle line using LSS, resulting in a higher

rate of production. The depot can now produce 32

mission-ready vehicles per day compared with three

a week in 2004.20

U.S. Army Recruiting Command also reduced the

number of steps it takes to process new recruits by

66%. It also decreased the time it takes to get applicants through the process by 40%. Finally, during

W e a p o n Ag a i n st W as t e

fiscal year 2005, Army Materiel Command saved $110

million by implementing LSS and removing waste by

better controlling output.21

Continuing improvement

The OBT strongly emphasizes continuous process

improvement (CPI), which includes such activities as:

1. Benefit reporting and tracking.

2. Ongoing performance measurement and reporting.

3. Institutionalization of new roles and responsibilities.

4. Identification of additional competencies.

5. Improved communication processes.

6. Ongoing risk assessment.

7. Formalized knowledge transfer and learning processes.

8. Formalized lessons-learned processes.

9. Identification of areas that need further improvement.

10. Reassessed customer needs and expectations.22

Although the Army has achieved many successes

in applying LSS, there are limitations to its full

implementation. Its not clear if there are sufficient

resources to support all potential LSS projects in

the Army. Its also unclear whether units would be

successful implementing all potential LSS projects in

an environment subject to frequent political changes.

LSS requires going beyond a simple mechanical

process. The Army still has the challenge of changing

the mindset of its personnel to accept this new way

of doing business. The OBT has not published the

number of GBs and BBs in the Army, and most of the

successes have been in the enterprise areas of manufacturing, production, logistics and acquisitions.

There have been no published studies to illustrate

whether operational units in the field have sufficient

expertise in LSS theories and whether there are sufficient numbers of LSS-trained soldiers and leaders

to use LSS in all of their operations.

Going forward, everyone should be exposed to LSS

and receive basic training because they are the ones

who are most familiar with how work is conducted in

their areas and thus would be the best candidates to

recommend ways to improve those operations.

resilient, expeditionary force that operates in a costmanagement culture. The leadership, complementary

culture and strong commitment inherent to the Army

have ensured the successes of LSS implementation

thus far.

Additionally, DoD Instruction No. 5010.438 facilitated the Armys senior leadership endorsement and

support for LSS. The recommended policy and procedures in effect for implementation have been set

in motion via the OBT, which resulted in numerous

successes since LSS was initiated. Further programs

of instruction, education and communication of LSS

will ensure the Army continues its success.

References

1. James Martin, Lean Six Sigma for Supply Chain Management, McGraw-Hill,

2007.

2. U.S. Army Office of Business Transformation, www.armyobt.army.mil.

3. U.S. Army, 2010 Army Posture Statement, Lean Six Sigma (LSS)/Continuous Process Improvement (CPI) Initiative, https://secureweb2.hqda.

pentagon.mil/vdas_armyposturestatement/2010/information_papers/

lean_six_sigma_(lss)_or_continuous_process_improvement_(cpi)_

initiative.asp.

4. U.S. Army, FM 1, The Strategic Environment and Army Organization,

2010, www.army.mil/fm1/chapter2.html#top.

5. Department of Defense Personnel and Procurement Statistics, Military

Personnel Statistics, 2010, http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/

MILITARY/miltop.htm (case sensitive).

6. Ibid.

7. George W. Bush, Executive Order (EO) 13450: Improving government

program performance, 2007, www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/

omb/assets/performance_pdfs/eo13450.pdf.

8. U.S. Army, Army Lean Six Sigma Deployment Guidebook, Jan. 14, 2011, www.

hqusareur.army.mil/leansixsigma/new%20site/training%20calendars/

deployment_guidebook_version_5.pdf.

9. U.S. Army, Lean Six Sigma: Our Strategy, 2008, www.armyg1.army.mil/

leansixsigma/default.asp.

10. U.S. Army, Lean Six Sigma (LSS)/Continuous Process Improvement

(CPI) Initiative, see reference 3.

11. Department of Defense, Implementation and Management of the DoDWide Continuous Process Improvement/Lean Six Sigma (CPI/LSS)

Program, 2009, www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/501043p.pdf.

12. U.S. Army, Army Lean Six Sigma Deployment Guidebook, see reference 8.

13. Army Office of Business Transformation, see reference 2.

14. Ibid.

15. Alexander B. Raulerson and Patti Sparks, Lean Six Sigma at Anniston

Army Depot, Army Logistician, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 6-9, 2006.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Beth Reece, Lean Six Sigma Eases Fiscal Constraint Challenges, July

20, 2006, www.military.com/features/0,15240,106262,00.html.

21. Ibid.

22. Army Office of Business Transformation, see reference 2.

The new Army

As with any major business management initiative, LSS

requires leadership buy-in from a top-down perspective. The Army has transitioned to become a more

What do you think of this article? Please share

your comments and thoughts with the editor by emailing

godfrey@asq.org.

six sigma forum magazine

february 2012

13

Você também pode gostar

- 0420 PV 201 Globe Valve Data SheetDocumento12 páginas0420 PV 201 Globe Valve Data SheetMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- LEANDocumento29 páginasLEANkmsteamAinda não há avaliações

- Lean Manufacturing Case StudyDocumento25 páginasLean Manufacturing Case StudyMohamed Farag Mostafa0% (1)

- BP West Nile DeltaDocumento2 páginasBP West Nile DeltaMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Transition To LeanDocumento27 páginasTransition To LeanMohamed Farag Mostafa100% (1)

- 05 - Internal AuditDocumento14 páginas05 - Internal AuditMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Syllabus 317Documento14 páginasSyllabus 317Mohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Solution Assignment 1Documento6 páginasSolution Assignment 1Mohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Distribution Channels:: Cookies Biscuits Flour Bread Sticks Fresh Bread Fresh PastaDocumento2 páginasDistribution Channels:: Cookies Biscuits Flour Bread Sticks Fresh Bread Fresh PastaMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Lean in Six StepsDocumento5 páginasLean in Six StepsMohamed Farag Mostafa100% (1)

- Statistics One: Repeated Measures ANOVADocumento23 páginasStatistics One: Repeated Measures ANOVAMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Year Demand 1 50.7 2 55.4 3 59.6 4 61 5 58 6 60.5 7 66 8 70.5 9 77.8 10 87.6 11 94.8 12 100.7Documento9 páginasYear Demand 1 50.7 2 55.4 3 59.6 4 61 5 58 6 60.5 7 66 8 70.5 9 77.8 10 87.6 11 94.8 12 100.7Mohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- Defining Areas of Analysis: The Entrepreneur Will Want To Understand The Nature of The Industry He or She Is AnalyzingDocumento27 páginasDefining Areas of Analysis: The Entrepreneur Will Want To Understand The Nature of The Industry He or She Is AnalyzingMohamed Farag MostafaAinda não há avaliações

- TQM Diploma AUCDocumento1 páginaTQM Diploma AUCMohamed Farag Mostafa0% (1)

- A Dose of DmaicDocumento8 páginasA Dose of DmaicDebu MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Ford Team Project Builds RelationshipsDocumento5 páginasFord Team Project Builds RelationshipsSandro Renato Espinoza MonsalveAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Writing Lesson PlanDocumento3 páginasWriting Lesson Planapi-252918385Ainda não há avaliações

- 11 2f9 6th Grade PLC Agenda and MinutesDocumento2 páginas11 2f9 6th Grade PLC Agenda and Minutesapi-365464044Ainda não há avaliações

- TASK 4 - ELP Assignment (Nur Izatul Atikah)Documento7 páginasTASK 4 - ELP Assignment (Nur Izatul Atikah)BNK2062021 Muhammad Zahir Bin Mohd FadleAinda não há avaliações

- Mai Le 22 Years and 27 PostsDocumento105 páginasMai Le 22 Years and 27 Postsdangquan.luongthanhAinda não há avaliações

- Daft12eIM - 16 - CH 16Documento27 páginasDaft12eIM - 16 - CH 16miah ha0% (1)

- Saloni LeadsDocumento3 páginasSaloni LeadsNimit MalhotraAinda não há avaliações

- By: Nancy Verma MBA 033Documento8 páginasBy: Nancy Verma MBA 033Nancy VermaAinda não há avaliações

- NITTTR PHD Within 7 YearsDocumento20 páginasNITTTR PHD Within 7 YearsFeroz IkbalAinda não há avaliações

- CV - Hendro FujionoDocumento2 páginasCV - Hendro FujionoRobert ShieldsAinda não há avaliações

- hlth634 Brief Marketing Plan Outline Jewel BrooksDocumento6 páginashlth634 Brief Marketing Plan Outline Jewel Brooksapi-299055548Ainda não há avaliações

- Personal Teaching PhilosophyDocumento4 páginasPersonal Teaching Philosophyapi-445489365Ainda não há avaliações

- Za HL 778 Phonics Revision Booklet - Ver - 3Documento9 páginasZa HL 778 Phonics Revision Booklet - Ver - 3Ngọc Xuân BùiAinda não há avaliações

- Michigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityDocumento52 páginasMichigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityThe Education Trust MidwestAinda não há avaliações

- SJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFDocumento25 páginasSJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFJulián JaramilloAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy and Logic: Atty. Reyaine A. MendozaDocumento19 páginasPhilosophy and Logic: Atty. Reyaine A. MendozayenAinda não há avaliações

- University of Gondar Academic Calendar PDF Download 2021 - 2022 - Ugfacts - Net - EtDocumento3 páginasUniversity of Gondar Academic Calendar PDF Download 2021 - 2022 - Ugfacts - Net - EtMuket AgmasAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan 50 Min Logo DesignDocumento3 páginasLesson Plan 50 Min Logo Designapi-287660266Ainda não há avaliações

- Regan Walton ResumeDocumento2 páginasRegan Walton Resumeapi-487845926Ainda não há avaliações

- Ok Sa Deped Form B (Dsfes)Documento10 páginasOk Sa Deped Form B (Dsfes)Maan Bautista100% (2)

- Lesson Plan & Academic EssayDocumento10 páginasLesson Plan & Academic EssaybondananiAinda não há avaliações

- Final Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Documento3 páginasFinal Score Card For MBA Jadcherla (Hyderabad) Program - 2021Jahnvi KanwarAinda não há avaliações

- WHLP Mapeh 6 Q1 W5Documento5 páginasWHLP Mapeh 6 Q1 W5JAN ALFRED NOMBREAinda não há avaliações

- Lac Sessions: General Tinio National High SchoolDocumento1 páginaLac Sessions: General Tinio National High SchoolFrancis JoseAinda não há avaliações

- B. Ed Final Prospectus Autumn 2019 (16-8-2019) PDFDocumento41 páginasB. Ed Final Prospectus Autumn 2019 (16-8-2019) PDFbilal1294150% (4)

- ĐỀ ĐẶC BIỆT KHÓA 2005Documento5 páginasĐỀ ĐẶC BIỆT KHÓA 2005phuc07050705Ainda não há avaliações

- LED vs. HIDDocumento6 páginasLED vs. HIDVictor CiprianAinda não há avaliações

- VGSTDocumento9 páginasVGSTrmchethanaAinda não há avaliações

- Anchor Chart PaperDocumento2 páginasAnchor Chart Paperapi-595567391Ainda não há avaliações

- Formulir Aplikasi KaryawanDocumento6 páginasFormulir Aplikasi KaryawanMahesa M3Ainda não há avaliações

- 156-Article Text-898-1-10-20230604Documento17 páginas156-Article Text-898-1-10-20230604Wildan FaisolAinda não há avaliações