Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Public Pension Plans: The Status of State Retirement Plans

Enviado por

The Council of State GovernmentsDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Public Pension Plans: The Status of State Retirement Plans

Enviado por

The Council of State GovernmentsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Issue Brief

The Council of State Governments

November 2007

Public Pension Plans

Very few topics generate as much interest

among both policymakers and the general

public as a discussion on the financial viability

of the United States retirement infrastructure. Research indicates that every element

of our nations retirement architecture, both

private and public, remains tenuousa development that demands the focus of policymakers at every level of government.

Public pension plans are an important component of the U.S. economic architecture.

This issue brief highlights the need for policymakers to focus on retirement systems, the

finances of state retirement systems, several

key developments and strategies employed

in states across the country to bolster the

finances of their pension systems.

The States Respond

The Status of State Retirement Plans

Consensus is growing across the country

that more attention needs to be directed

at developing a retirement infrastructure

with the capacity to meet the needs of all

Americans. The financial future of state

retirement systems requires the urgent

attention of policymakers.

Though states are in considerably better

financial shape than earlier this decade

when they faced their worst financial

downturn in 60 yearsthere are ominous

signs that point to another economic

downturn. Current state revenues lag

long-term historical trends, and a number

of states are already signaling the onset of

budget shortfalls. States now face surging

expenditures for health care, education,

retirement systems, corrections, transportation, emergency management and

infrastructure. The unfunded liability in

public pension plans remains yet another

item on the menu of expenditure categories that will continue to haunt states in

the coming years.

A review of national financial and demographic trends reveals that the U.S.

retirement architecture faces serious challenges. The weaknesses in public retirement systems, combined with the looming

shortfalls expected in Social Security and

Medicare, and the precarious financial

position of the federal Pension Benefit

Guaranty Corporation create troubling

situations for states. Also adding to

the mix are corporate pension plans,

the low personal savings rates of most

Americans, and high rates of consumer

and household debt.

Finances of State Retirement Systems

Recent research indicates the majority

of public pension plans are underfunded

or unfunded (i.e., assets are less than the

accrued liabilities). According to a 2004

Council of State Governments Southern

Legislative Conference 50-state report

titled Americas Public Retirement Systems:

Stresses in the System, 68 of the 93 plans

for which information was secured were

underfunded. In 2006, Barclays Global

Investments calculated the total value of

the benefits promised by states would

grow 22 percent to $2.5 trillion if state

pension plans were required to use the

same methods as corporations. States

have set aside only $1.7 trillion to pay

those benefits.

According to the 2007 Wilshire Report

on 125 state retirement systems, the

actuarial value funding ratio of plans declined from 103 percent in 2000 to 88

percent in 2006. Finally, according to the

September 2007 survey of 125 plans by the

National Association of State Retirement

Administrators, the actuarial funding ratio

of public pension plans stood at 86 percent

with a cumulative unfunded liability of $381

billion, an increase from the $337 billion

level recorded the year before. These different statistics cumulatively demonstrate

that currently public pension plan liabilities

currently exceed their assets.

However, it should be noted that in 2007

the assets in several public retirement

plans did exceed their accrued liabilities.

Specifically, according to a February 2007

Standard & Poors report, five state retirement systems saw an actuarial funding

ratio greater than 100 percent. These five

state retirement systems were Florida

(107 percent), North Carolina (106 percent), Oregon (104 percent), Delaware

(102 percent) and Georgia (100 percent).

At the other end of the spectrum, the five

states with the lowest funded pension

plans were West Virginia (47 percent),

Oklahoma (57 percent), Connecticut (58

percent), Illinois (58 percent) and Rhode

Island (59 percent).

Key Public Pension Trends

State plans are increasingly investing in

nongovernmental securities, such as corporate bonds, stocks and foreign investments, and moving away from government securities such as U.S. Treasury bills.

In 1993, only 62 percent of the total cash

and investment holdings of public plans

were in nongovernmental securities. That

investment grew to 88 percent in 2006.

Several states have moved to allow their

pension plans to invest more heavily in

nongovernment securities such as in the

equity market, real estate and foreign securities. For instance, in the last few years,

Georgia approved an increase from 50

percent to 60 percent; the South Carolina

Senate approved an increase from 40 percent to 70 percent; and Arkansas voted

to double its Teacher Retirement Systems

investments in real estate.

Given recent accounting and corporate scandals and the significant losses

experienced by public retirement systems, state lawmakers are more closely

monitoring the performance and management of these public systems. For

instance, Californias retirement plan, the

largest public pension system in the U.S.,

announced in October 2007 that it was

pressuring the Sara Lee Corporation

to grant its shareholders more clout in

changing company bylaws. In Maryland,

after the states employee pension system

Public Pension Plans

lost one-fifth of its total portfolio in a

15-month period, the Maryland General

Assembly began a series of inquiries.

These legislative explorations, along with

a federal investigation, led to the criminal

prosecution of a number of employees

and a complete overhaul of the plans

structure. As a result of management

changes and other reforms, Marylands

pension plan achieved the healthy growth

rate of nearly 18 percent by the end of

fiscal year 2007, the fourth consecutive

year of growth.

The Governmental Accounting Standards

Board Ruling 45 requires state and local governments to place a value on any post-employee retirement benefits, such as health

care. States and localities must also expense

the annual contribution required to fully

fund this long-term liability over 30 years.

While the private sector has operated under similar rules since 1992, the provisions of

the ruling took effect for state and local governments in 2007. Paired with rapidly rising

health care costs, the explosion in unfunded

liabilities as a result of this ruling is alarming.

Experts project that cumulatively, state and

local government liabilities for retiree health

care amount to a staggering $1 trillion.

An increasing number of states have also

either enacted legislation or are considering legislation prohibiting publicly managed

funds, such as pension funds, to be invested

in governments or companies associated

with terrorism or other national security

risks. In July 2006, Missouri became the first

state to ensure that its public pension fund

is terror-free. Two dozen additional states

either passed or considered similar legislation during the 2007 legislative sessions. In

September 2007, California Gov. Arnold

Schwarzenegger pledged to sign legislation

forcing the states two pension funds to shed

holdings of all companies that have energy

or military-related business in Iran.

State Pension Strategies

Responding to the growing crisis associated with pension liabilities, lawmakers

around the country have either proposed

or adopted strategies to buttress the finances of these systems.

For instance, several states and localities

have opted to issue pension obligation

bonds to pay off their unfunded liabilities

with a lump sum payment. Interest rates

continue to hover at historically low levels

and tax increases continue to be politically

unpopular, so the opportunity to raise

funds via enhanced borrowing quickly

became an attractive strategy for several

states. A number of states have deployed

this strategy in the past few years and

raised the following amounts via the pension obligation bond strategy to replenish

their pension plans: California ($2 billion),

Illinois ($10 billion), Kansas ($500 million),

Oregon ($2 billion) and Wisconsin ($1.8

billion). The payable interest on the pension obligation bonds needs to be less than

the pension investment earnings for states

to benefit. For instance, if a state pension

plan can earn 8 percent by investing money

borrowed at 6 percent, the state comes

out ahead. On the flip side, the market may

not generate enough returns to cover the

interest rate. In New Jersey, for instance,

the state issued $2.8 billion in bonds to

pay off its unfunded pension liability. But

when the economy slumped and the stock

market collapsed, the state experienced

a severe drop in investment earnings. By

mid-2003, even after the stock market had

recovered, the state experienced returns

of only 5.5 percent, significantly lower than

the 7.6 percent it needed.

States are also dealing with the pension crisis by trimming benefits. Some

states are moving employee benefits

away from defined benefit plans. Alaska

became the first state to move all state

workers hired after July 2006 from defined benefit plans to 401(k)-style defined contribution accounts. Lawmakers

in Illinois, Kentucky, Oregon and Virginia

have introduced bills to adopt this strategy for state employees.

A few states are tinkering with the link

between annual automatic percentage

increases in pension payments and the

www.trendsinamerica.org

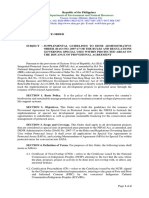

Cash & Investment Holdings of State & Local Government Employee Retirement Systems by

State & Level of Government: Fiscal Years 1993, 1999 and 2006 (Dollars in Thousands)

1993

United States

1999

% Change

1993-1999

2006

% Change

1999-2006

% Change

1993-2006

1993

1999

% Change

1993-1999

2006

% Change

1999-2006

% Change

1993-2006

$920,571,814

$1,906,049,268

107%

2,896,965,114

52%

215%

Mississippi

$117,497

$13,294,761

11215%

24,081,088

81%

20395%

State

$741,741,645

$1,581,779,624

113%

2,408,735,141

52%

225%

Missouri

$15,157,591

$32,002,742

111%

57,580,921

80%

280%

Local

$178,830,169

$324,269,644

81%

488,229,973

51%

173%

Montana

$2,181,531

$3,381,443

55%

7,068,244

109%

224%

Alabama

$11,823,629

$21,677,232

83%

28,866,974

33%

144%

Nebraska

$3,593,718

$6,689,440

86%

9,565,427

43%

166%

$4,909,179

$11,126,568

127%

21,656,244

95%

341%

$7,122

$3,991,857

55950%

5,251,746

32%

73640%

Alaska

$6,095,907

$9,782,827

61%

14,799,314

51%

143%

Nevada

Arizona

$12,974,566

$30,317,176

134%

32,500,260

7%

151%

New Hampshire

Arkansas

$5,412,022

$10,974,243

103%

17,616,485

61%

226%

New Jersey

$27,282,124

$50,411,042

85%

57,430,047

14%

111%

California

$168,062,846

$323,298,333

92%

563,265,118

74%

235%

New Mexico

$5,600,442

$11,499,926

105%

20,236,745

76%

261%

Colorado

$14,515,067

$22,785,624

57%

43,462,858

91%

199%

New York

$122,504,335

$204,568,749

67%

343,678,005

68%

181%

Connecticut

$11,089,818

$20,023,268

81%

28,562,577

43%

158%

North Carolina

$21,316,986

$52,554,025

147%

67,729,781

29%

218%

Delaware

$2,236,158

$5,277,729

136%

6,135,813

16%

174%

North Dakota

$1,232,231

$2,531,824

106%

3,653,802

44%

197%

DC

$2,136,629

$4,349,068

104%

6,494,734

49%

204%

Ohio

$57,686,802

$94,330,530

64%

149,874,270

59%

160%

Florida

$34,442,622

$82,561,986

140%

135,805,678

65%

294%

Oklahoma

$6,137,798

$14,188,085

131%

20,156,653

42%

228%

Georgia

$19,101,627

$42,870,979

124%

67,047,834

56%

251%

Oregon

$8,653,315

$17,479,470

102%

56,355,470

222%

551%

Hawaii

$5,036,156

$9,494,258

89%

12,681,533

34%

152%

Pennsylvania

$39,689,227

$83,607,419

111%

103,314,191

24%

160%

Idaho

$2,190,558

$6,527,504

198%

9,618,449

47%

339%

Rhode Island

$515,963

$7,245,508

1304%

9,632,652

33%

1767%

Illinois

$42,889,924

$76,398,583

78%

126,956,280

66%

196%

South Carolina

$14,126,901

$18,565,873

31%

30,247,191

63%

114%

Indiana

$7,909,641

$14,435,253

83%

27,672,065

92%

250%

South Dakota

$1,901,500

$5,036,039

165%

7,300,075

45%

284%

Iowa

$6,484,147

$18,469,930

185%

23,449,948

27%

262%

Tennessee

$11,454,862

$28,382,345

148%

35,950,936

27%

214%

Kansas

$4,246,029

$8,601,374

103%

13,627,374

58%

221%

Texas

$45,964,742

$127,543,228

178%

167,531,478

31%

265%

Kentucky

$9,499,690

$22,162,266

133%

29,896,744

35%

215%

Utah

$4,593,987

$11,398,687

148%

18,657,043

64%

306%

Louisiana

$11,265,735

$24,714,174

119%

33,165,473

34%

194%

Vermont

$908,614

$1,997,292

120%

3,041,075

52%

235%

Maine

$2,306,026

$6,901,936

199%

9,528,945

38%

313%

Virginia

$17,509,170

$43,470,398

148%

58,427,770

34%

234%

Maryland

$17,749,193

$39,078,626

120%

47,012,213

20%

165%

Washington

$17,195,454

$44,691,362

160%

59,593,696

33%

247%

Massachusetts

$13,853,875

$38,626,867

179%

58,032,061

50%

319%

West Virginia

$103,500

$3,792,905

3565%

3,894,750

3%

3663%

Michigan

$31,616,109

$68,579,060

117%

80,779,584

18%

156%

Wisconsin

$26,635,774

$60,063,438

126%

79,755,515

33%

199%

Minnesota

$18,702,864

$40,846,329

118%

52,089,647

28%

179%

Wyoming

$1,950,611

$3,449,687

77%

6,232,338

81%

220%

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census

Note 1: There were 2,213 public employment retirement systems in the 1993 survey, 2,209 systems in the 1999 survey and 2,654 systems in the 2006 survey.

Note 2: As of September 28, 2007, the 2006 (June 30, 2006) survey was the latest compilation of data on the cash and investment holdings of state and local government employee

retirement systems.

The Council of State Governments

www.csg.org

Consumer Price Index (CPI). In 2006,

Colorado agreed to maintain its defined

benefit pension plan, but in turn employees agreed to forego scheduled cost-ofliving raisesworth 3 percent of their

incomeand instead put the money into

the pension fund. Also in 2006, Arizona

informed thousands of its retired employees that they would not receive cost-ofliving raises for the next five years.

Several states are adjusting the age at

which employees are paid full benefits.

Colorado increased its minimum retirement age by five years, from 50 to 55, in

2006. In Kansas, beginning July 1, 2009, the

retirement age for state employees will increase to 60 with 30 years service or to 65

with five years service. Currently, Kansas

employees can retire when their age plus

years of service equals 85. In Illinois, the

governor has proposed raising the age of

retirement from 60 to 65. Similarly, Rhode

Island Gov. Donald L. Carcieri has proposed instituting a minimum retirement

age of 60 years at 30 years service or otherwise, at age 65. Texas passed legislation

prohibiting school districts from offering

early retirement and requiring educators

to be at least 60 before retiring with full

benefits. Louisiana has also proposed

pushing back the age at which teachers

can get retirement benefits. When states

increase their retirement ages, they defer

having to make pension payments while

diminishing the growth rate of their accrued liabilities.

In a contrary approach, Maine became

the first state to adopt a strategy known

as matching, or deliberately aiming for low,

guaranteed investment income to pay for

the retirement benefits of state workers.

In 2003, Maine put a third of its assets into

very conservative bonds. The bonds pay a

low interest rate, but their values will rise

or fall in conjunction with the value of the

pensions the state must pay its retirees

regardless of how the markets fluctuate.

A few states are making unorthodox investments in an effort to generate greater

returns for their pension plans. The

Retirement System of Alabama embarked

on a series of investments that enabled the

fund to progress from $500 million in assets in 1973 to $28.1 billion by September

2006. Some of these acquisitions include

New York City real estate, media outlets including television and newspapers,

hotels, a cruise ship terminal and golf

courses. The system also became the larg-

Trends in America

est stakeholder of US Airways. Similarly,

Massachusetts considered a proposal to

open the states public employee pension

fund$48.2 billion as of March 2007to

all state residents for investment purposes. And New Jersey considered shifting

about a quarter of its $79.2 billionas of

June 30, 2006pension fund from state

employee control to professional money

managers in 2006.

The Future of State Pensions

Unfunded and underfunded pension liabilities continue to plague nearly every

state. Factors in the weakened pension

outlook include skipped required state

contributions, the severity of the recent

fiscal downturn, demographic changes and

the steep rise in health care costs. The

implementation of the GASB ruling could

propel unfunded pension liability levels to

new heights beginning in 2007a trend

that could damage state bond ratings.

Yet, the aging of American workers, the

increased number of retirees living longer

in the coming years, and the ability of

the public sector to attract quality employees in an era of dwindling retirement

benefits requires innovative actions by

states. Ensuring both the short-term and

long-term financial viability of the different

elements in Americas retirement systems,

both private and public, remains of paramount importance.

Sujit CanagaRetna is a senior

f iscal analyst at The Council of

State Governments Southern

Legislative Conference.

The most dominant characteristic of the 21st century is not just change, but the rate of

change. Understanding change is the first step toward identifying and implementing

effective responses. Trends in America Issue Briefs are designed to help state leaders

promote positive change through forward-looking policies and strategic investments.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Body-Worn Cameras: Laws and Policies in The SouthDocumento24 páginasBody-Worn Cameras: Laws and Policies in The SouthThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- CLEMENTE CALDE vs. THE COURT OF APPEALSDocumento1 páginaCLEMENTE CALDE vs. THE COURT OF APPEALSDanyAinda não há avaliações

- Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche - Meditation On EmptinessDocumento206 páginasKhenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche - Meditation On Emptinessdorje@blueyonder.co.uk100% (1)

- Principles of Marketing: Quarter 1 - Module 6: Marketing ResearchDocumento17 páginasPrinciples of Marketing: Quarter 1 - Module 6: Marketing ResearchAmber Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Agreement of PurchaseDocumento8 páginasAgreement of PurchaseAdv. Govind S. TehareAinda não há avaliações

- The Growth of Synthetic Opioids in The SouthDocumento8 páginasThe Growth of Synthetic Opioids in The SouthThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- The Netherlands Model: Flood Resilience in Southern StatesDocumento16 páginasThe Netherlands Model: Flood Resilience in Southern StatesThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Issues To Watch 2020Documento8 páginasIssues To Watch 2020The Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Surprise Medical Billing in The South: A Balancing ActDocumento16 páginasSurprise Medical Billing in The South: A Balancing ActThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Sports Betting in The SouthDocumento16 páginasSports Betting in The SouthThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Rural Hospitals: Here Today, Gone TomorrowDocumento24 páginasRural Hospitals: Here Today, Gone TomorrowThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Scoot Over: The Growth of Micromobility in The SouthDocumento12 páginasScoot Over: The Growth of Micromobility in The SouthThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Opioids and Organ Donations: A Tale of Two CrisesDocumento20 páginasOpioids and Organ Donations: A Tale of Two CrisesThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Weathering The Storm: Assessing The Agricultural Impact of Hurricane MichaelDocumento8 páginasWeathering The Storm: Assessing The Agricultural Impact of Hurricane MichaelThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Long-Term Care in The South (Part II)Documento16 páginasLong-Term Care in The South (Part II)The Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- By Roger Moore, Policy AnalystDocumento6 páginasBy Roger Moore, Policy AnalystThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Blown Away: Wind Energy in The Southern States (Part II)Documento16 páginasBlown Away: Wind Energy in The Southern States (Part II)The Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Education Comparative Data ReportDocumento69 páginas2017 Education Comparative Data ReportThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Medicaid Comparative Data ReportDocumento125 páginas2017 Medicaid Comparative Data ReportThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Performance ManagementDocumento6 páginasTransportation Performance ManagementThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- By Roger Moore, Policy AnalystDocumento16 páginasBy Roger Moore, Policy AnalystThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Ensuring Federal Consultation With The StatesDocumento3 páginasEnsuring Federal Consultation With The StatesThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- By Roger Moore, Policy AnalystDocumento16 páginasBy Roger Moore, Policy AnalystThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- SLC Report: Wind Energy in Southern StatesDocumento8 páginasSLC Report: Wind Energy in Southern StatesThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Emerging State Policies On Youth ApprenticeshipsDocumento3 páginasEmerging State Policies On Youth ApprenticeshipsThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Long-Term Care in The South (Part 1)Documento20 páginasLong-Term Care in The South (Part 1)The Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Corrections and Reentry, A Five-Level Risk and Needs System ReportDocumento24 páginasCorrections and Reentry, A Five-Level Risk and Needs System ReportThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Reducing The Number of People With Mental IllnessesDocumento16 páginasReducing The Number of People With Mental IllnessesThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- CSG Capitol Research: Workforce Development Efforts For People With Disabilities: Hiring, Retention and ReentryDocumento4 páginasCSG Capitol Research: Workforce Development Efforts For People With Disabilities: Hiring, Retention and ReentryThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Commuter Rail in The Southern Legislative Conference States: Recent TrendsDocumento12 páginasCommuter Rail in The Southern Legislative Conference States: Recent TrendsThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- 2016 Medicaid Comparative Data ReportDocumento185 páginas2016 Medicaid Comparative Data ReportThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- The Case For CubaDocumento24 páginasThe Case For CubaThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- CSG Capitol Research: Child Care ConclusionDocumento5 páginasCSG Capitol Research: Child Care ConclusionThe Council of State GovernmentsAinda não há avaliações

- Planning and Design of A Cricket StadiumDocumento14 páginasPlanning and Design of A Cricket StadiumTenu Sara Thomas50% (6)

- Child Health Services-1Documento44 páginasChild Health Services-1francisAinda não há avaliações

- Simple FTP UploadDocumento10 páginasSimple FTP Uploadagamem1Ainda não há avaliações

- Math 3140-004: Vector Calculus and PdesDocumento6 páginasMath 3140-004: Vector Calculus and PdesNathan MonsonAinda não há avaliações

- Wa0009.Documento14 páginasWa0009.Pradeep SinghAinda não há avaliações

- State Public Defender's Office InvestigationDocumento349 páginasState Public Defender's Office InvestigationwhohdAinda não há avaliações

- Hotel BookingDocumento1 páginaHotel BookingJagjeet SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Ips Rev 9.8 (Arabic)Documento73 páginasIps Rev 9.8 (Arabic)ahmed morsyAinda não há avaliações

- 4h Thank You ProofDocumento1 página4h Thank You Proofapi-362276606Ainda não há avaliações

- Bed BathDocumento6 páginasBed BathKristil ChavezAinda não há avaliações

- Romeuf Et Al., 1995Documento18 páginasRomeuf Et Al., 1995David Montaño CoronelAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1Documento8 páginasChapter 1Shidan MohdAinda não há avaliações

- Kami Export - Tools in Studying Environmental ScienceDocumento63 páginasKami Export - Tools in Studying Environmental ScienceBenBhadzAidaniOmboyAinda não há avaliações

- AN6001-G16 Optical Line Terminal Equipment Product Overview Version ADocumento74 páginasAN6001-G16 Optical Line Terminal Equipment Product Overview Version AAdriano CostaAinda não há avaliações

- Anthem Harrison Bargeron EssayDocumento3 páginasAnthem Harrison Bargeron Essayapi-242741408Ainda não há avaliações

- 08-20-2013 EditionDocumento32 páginas08-20-2013 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Draft DAO SAPA Provisional AgreementDocumento6 páginasDraft DAO SAPA Provisional AgreementStaff of Gov Victor J YuAinda não há avaliações

- Composition PsychologyDocumento1 páginaComposition PsychologymiguelbragadiazAinda não há avaliações

- Chessboard PDFDocumento76 páginasChessboard PDFAlessandroAinda não há avaliações

- SyerynDocumento2 páginasSyerynHzlannAinda não há avaliações

- Persian NamesDocumento27 páginasPersian NamescekrikAinda não há avaliações

- NR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionDocumento49 páginasNR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionKent GallardoAinda não há avaliações

- Co-Publisher AgreementDocumento1 páginaCo-Publisher AgreementMarcinAinda não há avaliações

- Waa Sik Arene & Few Feast Wis (FHT CHT Ste1) - Tifa AieaDocumento62 páginasWaa Sik Arene & Few Feast Wis (FHT CHT Ste1) - Tifa AieaSrujhana RaoAinda não há avaliações

- Campos V BPI (Civil Procedure)Documento2 páginasCampos V BPI (Civil Procedure)AngeliAinda não há avaliações

- COSMO NEWS September 1, 2019 EditionDocumento4 páginasCOSMO NEWS September 1, 2019 EditionUnited Church of Christ in the PhilippinesAinda não há avaliações