Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Descubriendo Pedagogías de Contenido y Conocimiento

Enviado por

AndrésJimenezMamaniTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Descubriendo Pedagogías de Contenido y Conocimiento

Enviado por

AndrésJimenezMamaniDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

This article was downloaded by: [University of Nottingham]

On: 13 May 2013, At: 13:38

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,

UK

Journal of the Learning

Sciences

Publication details, including instructions for

authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hlns20

Developing and Enacting

Pedagogical Content Knowledge

for Teaching History: An

Exploration of Two Novice

Teachers' Growth Over Three

Years

a

Chauncey Monte-Sano & Christopher Budano

Department of Educational Studies, University of

Michigan

b

Department of Teaching, Learning, Policy, and

Leadership, University of Maryland

Accepted author version posted online: 31 Oct

2012.Published online: 20 Dec 2012.

To cite this article: Chauncey Monte-Sano & Christopher Budano (2013): Developing

and Enacting Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Teaching History: An Exploration

of Two Novice Teachers' Growth Over Three Years, Journal of the Learning Sciences,

22:2, 171-211

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2012.742016

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.

Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan,

sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is

expressly forbidden.

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any

representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to

date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be

independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable

for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages

whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection

with or arising out of the use of this material.

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

THE JOURNAL OF THE LEARNING SCIENCES, 22: 171211, 2013

Copyright Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1050-8406 print / 1532-7809 online

DOI: 10.1080/10508406.2012.742016

Developing and Enacting Pedagogical

Content Knowledge for Teaching History:

An Exploration of Two Novice Teachers

Growth Over Three Years

Chauncey Monte-Sano

Department of Educational Studies

University of Michigan

Christopher Budano

Department of Teaching, Learning, Policy, and Leadership

University of Maryland

Using artifacts of teachers practices, classroom observations, and teacher interviews, we explore the development and enactment of 2 novices pedagogical content

knowledge (PCK) for teaching history. We identify and track 4 components of

PCK that are relevant to teaching history: representing history, transforming history, attending to students ideas about history, and framing history. We find that

these 2 novices demonstrated different aspects of PCK in different settings at different points in the first 3 years of their careers. Their PCK continued to grow

after preservice education, although the pace and substance of this development

varied. In particular, attending to students ideas about history and framing history

were more challenging aspects of PCK for these novices. Specific features of the

teacher education program, the school context, and the individual teachers capacity facilitate growth in PCK, including opportunities to practice, alignment within

the teacher education program and across learning sites, reflection on practice, and

subject matter knowledge.

A very learned man may profoundly understand a subject himself, and yet fail egregiously in elucidating it to others.1861 petition to the California Superintendent

Christopher Budano is now at the Pennsylvania State Education Association.

Correspondence should be addressed to Chauncey Monte-Sano, Department of Educational

Studies, University of Michigan, 610 East University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259. E-mail:

cmontesa@umich.edu

172

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

of Public Instruction by the Committee on State Normal Schools (as quoted in

McDiarmid & Clevenger-Bright, 2008, p. 134)

The range of knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to effectively teach

students has been framed in different ways over time but has only recently been

studied (C. Grant, 2008; Howard & Aleman, 2008; McDiarmid & ClevengerBright, 2008). In this article we focus on pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) as

one form of knowledge that contributes to teachers success in supporting student

learning (Shulman, 1986). Most researchers and teacher educators agree that PCK

is a core component of teachers knowledge base. More recently, scholars have

argued that the importance of this knowledge is most apparent in its enactment

(Ball & Forzani, 2009; Grossman, Hammerness, & McDonald, 2009).

Frameworks that characterize the knowledge that teachers draw upon often

include PCK (cf. Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2005). But only a handful of

history researchers discuss PCK directly in their analyses of teachers or conduct

longitudinal studies of new teacher learning. The field has yet to create a coherent statement of what PCK for teaching history entails, conceptualize how new

teachers develop PCK, or consider what such knowledge development involves.

Here we look across existing research to create a synthesis of the PCK that is

most relevant to teaching history. Then we examine how two novice history teachers developed and enacted these aspects of PCK in their preservice program and

first 2 years of teaching after graduation. Our goal in this article is to create an

integrated statement that outlines key aspects of PCK for teaching history and to

identify salient issues that emerged as two new history teachers developed and

enacted this PCK over 3 years.

BACKGROUND

First we share a sample of literature that has helped us consider the nature and

characteristics of PCK. This is certainly not an exhaustive review of literature,

but it is intended to clarify work that has heavily influenced our thinking. With

this article, we seek to build on this literature by extending these ideas to history

education more specifically.

Shulman (1986) characterized PCK as subject matter knowledge for teaching (p. 9). He explained that PCK involves both the ways of representing and

formulating the subject that make it comprehensible to others as well as an

understanding of what makes the learning of specific topics easy or difficult

(p. 9). In practice, PCK helps teachers create lessons that advance students subject

matter understanding, notice students misconceptions, and develop pedagogical

responses that support students learning. Such knowledge enables teachers to

work in the spaces in which teaching, content, and students intersect.

Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2008) defined PCK more explicitly as they sought

to measure it. In defining mathematical knowledge for teaching, they included

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

173

subject matter knowledge and PCK and broke both down into smaller subsets of

knowledge. Ball and her colleagues built on Shulmans work by defining specific

constructs integral to mathematics teachers PCK and subject matter knowledge.

To Ball et al., PCK in mathematics includes knowledge of content and students, knowledge of content and teaching, and knowledge of curriculum.

Knowledge of content and students refers to teachers understanding of student

thinking about the subject area, whereas knowledge of content and teaching

focuses on teachers instructional choices, such as responding to a students idea.

Teacher knowledge and teacher learning research have not yet been a major

focus of the learning sciences field, but the fields emphasis on situated learning

and domain-specific knowledge and learning positions the learning sciences to

make important contributions in this area (Fishman & Davis, 2006). Although several researchers have focused on the design of learning environments that promote

teacher learning (e.g., Chieu, Herbst, & Weiss, 2011; Cobb, Zhao, & Dean, 2009),

there is still work to be done in order to define and elaborate on the substance and

nature of teachers development of domain-specific knowledge.

Seymour and Lehrer (2006) tracked an experienced teachers efforts to support her students understanding of linear functions over 2 years. The researchers

focused on the teachers recognition of, thinking about, and responses to students

interpretations of math and in doing so tracked one key aspect of PCK. They found

that the teacher initially responded to students in general ways, but her reactions

became more productive and responsive over time in ways that supported students understanding of math. This study highlighted the domain-specific nature

of teacher learning and the capacity of a teacher to learn in and through practice. Related work has emphasized other aspects of the domain-specific teacher

knowledge required for teaching (e.g., Sherin, 2002), but the majority of learning sciences research has emphasized the social and situated aspects of teacher

learning (Fishman & Davis, 2006).

PCK IN THE HISTORY EDUCATION LITERATURE

Using Shulmans definition of PCK and Ball et al.s (2008) math-specific framework as a baseline, here we consider the literature on history education and

synthesize aspects of PCK that are relevant for teaching history. We analyze the

history education literature and organize it into four components of PCK that

emerged from these analyses: representing history, transforming history, attending

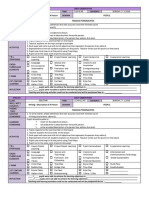

to students ideas about history, and framing history. Table 1 presents our delineation of PCK and highlights its basis in the history education literature and how

it maps onto definitions of PCK outside of this domain. First we discuss each

component of PCK as it is shared in the history education literature and then we

examine these components in two novice world history teachers classrooms to

174

Teachers select and arrange topics of study into a coherent story that

conveys causeeffect relationships between and among events as

well as the historical significance of events and people. In so doing

they conceptualize and frame the history curriculum to illustrate

significance, connections, and interrelationships.

Frame history

Note. PCK = pedagogical content knowledge.

Ideally, teachers identify and respond to students thinking about

history in order to build on students incoming ideas and

experiences, address misconceptions, develop students

understanding further, and promote historical ways of thinking.

Attending to student thinking requires teachers to not only notice

students thinking but take up and respond to students thinking in

some way.

The ways in which teachers communicate to students what history

involves and, in particular, the nature of historical knowledge, the

structure of history as a discipline, and historical ways of thinking.

Teachers recognition of students ideas, selection of materials,

organization of content and activities, and daily learning tasks

provide representations of the discipline that convey information

about the nature of knowledge in history and the work of historians.

How teachers transform historical content into lessons and materials

that target the development of students historical understanding

and thinking and give students appropriate opportunities to achieve

these goals.

Definition

Attend to students

ideas about

history

Transform history

Represent history

PCK for Teaching

History

Bain & Harris (2009), Harris & Bain

(2011)

Calder (2006)

Gudmundsdottir & Shulman (1987)

Wilson (1988), Wilson & Wineburg

(1988)

Bain (2005, 2006)

Fehn & Koeppen (1998)

S. G. Grant & Gradwell (2005)

Monte-Sano & Cochran (2009)

Seixas (1998)

VanSledright (2002)

Wilson & Wineburg (1993)

Bain (2005, 2006)

Barton et al. (2004)

Halldn (1998)

Monte-Sano (2011b)

Seixas (1994)

VanSledright (2002)

Gudmundsdottir (1990)

Monte-Sano & Cochran (2009),

Monte-Sano (2011b)

VanSledright (2002)

Wineburg & Wilson (1991), Wilson &

Wineburg (1988, 1993)

Related History Education

Literature

TABLE 1

Key Aspects of PCK for Teaching History and Examples From the Research Literature

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

Ball et al. (2008) (knowledge

of content and students)

Franke & Kazemi (2001)

Grossman (1990)

Levin, Hammer, & Coffey,

(2009)

Sherin & Han (2004)

Shulman (1986, 1987)

Ball et al. (2008) (knowledge

of curriculum)

Shulman (1986, 1987)

Ball et al. (2008) (knowledge

of content and students)

Grossman (1990)

Shulman (1986, 1987)

Ball et al. (2008) (knowledge

of content and teaching)

Borko et al. (1992)

Grossman (1990)

Shulman (1986, 1987)

Wilson et al. (1987)

Related Education Literature

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

175

illustrate the challenges and particular areas of learning with which new teachers

must contend.

One area of PCK that history education research has explored involves the

ways in which teachers communicate to students what history involves and, in

particular, how one knows in history (the epistemology of history). Teachers

recognition of students incoming ideas, selection of materials, organization of

content and activities, and daily learning tasks provide representations of the discipline that convey information about the nature of knowledge in history and

the work of historians (cf. Gudmundsdottir, 1990; Shulman, 1986). We refer to

this aspect of PCK as representing history. Wineburg and Wilson (1991) showed

how two veteran history teachers used their awareness of students disciplinary

knowledge, subject matter knowledge, and pedagogical expertise to represent the

subject in ways that advanced students understandings. Whereas one teacher

held a student-led debate about the British right to tax the colonies, another

led a whole-class exploration of a time period and conflicting primary sources

from it. Although the teachers styles differed, both lessons represented history as

constructed and the students role as analysts who deliberate and ask questions.

Similarly, Monte-Sano (2008, 2011a) reported on the work of two experienced

teachers whose design of classroom activities and assignments represented the

interpretive, evidentiary nature of history. Whether through whole-class discussions or individual or group work, these teachers put students in the role of

deliberating among conflicting accounts, asking questions, and constructing their

own interpretations. Such representations of history facilitated growth in students

written historical arguments.

In two reports that compared new teachers (Monte-Sano & Cochran, 2009;

Monte-Sano & Harris, 2012), one novice represented history in authentic ways

in his classrooms even while student teaching, and another improved in this area

in her first 2 years of teaching. This study suggests that new teachers are capable of making pedagogical choices that represent history in authentic ways (e.g.,

conducting investigations using primary documents). However, novices subject

matter knowledge, views of students, and local school contexts influence the

extent to which their lessons represent the discipline.

Another area of research into PCK has focused primarily on novices skills in

transforming history content into lessons and materials that target the development

of students historical understanding and thinking (i.e., transforming history). Ball

et al. (2008) might consider this knowledge of content and teaching. Several

studies have looked at novices selection of historical documents and use of

them in lessons (Fehn & Koeppen, 1998; S. G. Grant & Gradwell, 2005; Seixas,

1998; VanSledright, 2002). Seixas (1998) explored the challenges teacher candidates face when trying to design primary sourcebased exercises for students.

Teacher candidates in their first semester selected primary sources and constructed

a sequence of questions in order to teach a particular concept they defined. Of the

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

176

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

four candidates Seixas (1998) examined in depth, all selected texts that could lead

to productive historical interpretation, but only two constructed tasks that helped

students use the historical context to understand the text and created questions

that would help students delve into the historical meaning of the texts. Fehn and

Koeppen (1998) found that all 11 student teachers in their study used primary

sources in their teaching to enliven their instruction and to develop students skills

in interpreting texts. Although all participants were enthusiastic about using primary sources, they did not feel that they could use sources as often as they had

expected given the realities and norms of their field placements. S. G. Grant and

Gradwell (2005) found that two third-year teachers both used a wide variety of primary and secondary sources regularly. The teachers selection of texts was largely

influenced by their subject matter knowledge and their perception of students

interests and skills. Although one teacher used the states standardized test in history to guide her selection of documents, the other did not. Together these studies

suggest that novices are capable of teaching with historical sources but attend to

students interests in their selection and use of documents and are influenced by

the contexts in which they teach to varying degrees. New teachers may be able

to find historical sources on a particular topic, but designing lessons around those

documents that support students learning is a more complicated task and relies

on key aspects of PCK.

A handful of history education researchers have also examined novice history

teachers consideration of students thinking, what we refer to as attending to

students ideas about history (i.e., what Ball et al., 2008, referred to as knowledge of content and students). Seixas (1994) shared an interview protocol that

his student teachers used to explore their students prior historical understandings

and how those teachers made sense of students responses. Teacher candidates

noticed three issues in their students thinking: Students think in terms of progress

and decline and connect to issues of social justice in the more recent past, but

they do not discriminate among historical accounts in terms of their reliability or

validity. The interviews gave candidates some understanding of students incoming conceptions of history and experience with questioning and pushing students

thinking. Barton, McCully, and Marks (2004) found that having beginning teachers complete structured investigations with elementary school students not only

gave teachers more insight into students thinking but also helped them think

about proactively playing a role in developing students ideas. Yet Monte-Sano

and Cochran (2009) found that asking teacher candidates to interview secondary

students or analyze students work did not necessarily mean that the candidates

noticed their students disciplinary thinking. And those who do may not respond

to their students thinking with appropriate pedagogical choices in the classroom.

Monte-Sano (2011b) analyzed three student teachers approaches to history education in preservice coursework and classroom practice. Although teachers were

able to learn over time to identify features of their students disciplinary thinking,

responding to that thinking in the classroom was more challenging. Together these

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

177

studies reveal that new teachers can notice their students disciplinary thinking but

may not do so in the classroom or if not prompted by course assignments.

One final aspect of PCK that we explore is a teachers skill in selecting and

arranging topics of study into a coherent story that conveys the connections and

interrelationships between events as well as the historical significance of events

and people. We call this framing history. Ball et al. (2008) might have included

this in their category knowledge of curriculum. Wilson (1988) analyzed the

subject matter knowledge that supports this kind of pedagogical reasoning in her

dissertation work. She referred to this knowledge as integration, or the ability

to recognize patterns, themes, causal links, and issues of significance in history.

Gudmundsdottir and Shulman (1987) explored this aspect of PCK with two U.S.

history teachers. They reported on an experienced teacher who used his knowledge of U.S. history to select key topics, arrange it in comprehensible chunks, and

structure an overall story that would help students understand key issues in U.S.

history. This teacher also saw that there are multiple ways to segment and organize a U.S. history course, each with its own affordances and limitations. The other

teacher, with weaker subject matter knowledge and no experience, was unable to

discern more or less critical topics that would develop students understanding or

identify alternative ways to organize the curriculum. He did not conceptualize the

course as a whole but rather focused on one unit at a time.

More recent work has investigated the particular challenges of teaching world

history and has brought this aspect of PCK to the forefront once again. Bain and

Harris (2009) explained that the importance of having a big picture to help situate all the details that so define history at any level is particularly challenging in

world history (p. 34). World history teachers grapple with decisions about where

to begin, what to include, which perspectives or regions to represent, which time

periods to cover, and how to link the various topics that could compose a world

history class. Dunn (2008) explained that a big part of the challenge lies in defining and framing world history. Traditionally, world history has often been regarded

as a place to teach about Western heritage and, more recently, multiculturalism.

Yet since 1960, a new approach to world history has taken shape that emphasizes

patterns and comparisons across space and time rather than any one history of a

people or region. The new world history has taken root in the Advanced Placement

world history exam and has had some effect on schools through university-based

professional development, but the more traditional approach to world history has

historically been more influential in the policy arena.

Harris and Bain (2011) sought to identify how teachers arrange world history knowledge for teaching and compared how novice and experienced teachers

arranged a series of cards with different world history events and concepts on

them. They found that the more experienced teachers used the cards to construct a

coherent story of the past, made connections between events and concepts, linked

the cards to students understandings, and organized these ideas into segments

suitable for instruction. Novices were far less able to conceptualize world history

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

178

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

in meaningful, complex, and coherent ways for themselves or for instructional

purposes. They were more likely to place events in chronological order and made

very few connections between different events. Participating in professional development or using curriculum that approached world history on a global scale may

have been a contributing factor that enabled more experienced teachers to make

multiple connections. Together these studies show that conceptualizing the subject matter with an eye toward illustrating links, connections, and significance is

a key aspect of PCK that may take time for novices to develop. Based on existing research, we do not know whether history teachers with different areas of

emphasis (e.g., world or U.S.) rely on the same aspects of PCK equally.

The history education literature helps us elaborate on foundational and recent

work in defining PCK for teaching history. Four components of PCK emerged

through the analyses of the literature: representing history, transforming history,

attending to students ideas about history, and framing history. As a research community we do not understand how teachers PCK develops over time and which

aspects of PCK teachers draw on at different points in their development, nor do

we have a sense of new teachers growth beyond the teacher education program

experience.

Using these four components of PCK, we track two novices thinking and

practices to understand how their PCK develops. We look to their coursework,

interviews, and teaching to understand what components of PCK novices struggle

with and how the enactment of their knowledge changes over timeparticularly

in the first 2 years of teaching after preservice education. Specifically, we ask the

following: (a) What do the four components of PCK for teaching history look like

in two novices practice? (b) What components of PCK do these novice history

teachers enact in their teaching or draw on in their thinking about teaching? (c)

Do, or how do, the two novices PCK and enactment of PCK in the classroom

change over time?

METHOD

We use an exploratory multiple case study approach (Yin, 2003) to examine the

PCK of two novice high school history teachers during preservice and the 2 years

following their completion of their teacher education program. Individual case

analysis and comparison of cases used multiple units of analysis: interviews,

classroom observations, and classroom artifacts.

Participants

This article is a part of a longitudinal research project on history and social studies teachers learning. We followed 10 teacher candidates during their 1-year

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

179

teacher education program and continued with 6 of the 10 graduates (those who

remained in state with social studies teaching positions) during their first 2 years of

teaching. In this article we focus on Talia and Gabrielle because they both demonstrated growth in teaching history, yet their levels of expertise differed across time.

In addition, both Talia and Gabrielle taught world history to high school juniors in

the 2 years following preservice and invited us to observe units on the same topics:

political revolutions and World War I. Keeping the topics and courses constant for

two years allowed us to compare Talias and Gabrielles levels of expertise and

instructional decisions more directly as well as recognize changes in their teaching

over time.

For her preservice field placement, Talia taught one sociology class and two

U.S. history classes in a high school that had little administrative oversight of

the day-to-day operations and a high incidence of student disruptions. Seventyfive percent of the classes at this school were taught by teachers who were

highly qualified, and 85% of the students graduated. Although Talia had a mentor, he was a full-time teacher and typically spoke with her during a free period

instead of observing her teaching. Upon graduation, Talia moved to a better managed high school and taught U.S. and world history to 9th and 11th graders,

respectively; in this school, 89% of the classes were taught by teachers who

were highly qualified and 79% of the students graduated. In her second year

she started teaching a psychology course and continued teaching world history. A total of 53% of the students qualified for free and reduced-price meals.

The first school had a predominantly African American (83%) student population, and the second was an even mix of African American and Hispanic

students.

Gabrielle worked in the school where she did her student teaching in the years

following graduation. Her mentor was a consistent source of support and constructive criticism during and after classes throughout the student teaching year

and her first year of teaching. She taught world history to 11th graders during

her student teaching and in her first 2 years of full-time teaching. The student

population included African American (43%), Hispanic (36%), White, and Asian

American students (10%11% each). Moreover, 42% of students qualified for the

free and reduced-price meals program. Finally, 82% of students at Gabrielles

school graduated, and 92% of the classes were taught by highly qualified

teachers.

Talia and Gabrielle taught in different districts, each with its own history

curriculum. The two districts curricula focused on similar topics, but Talias

focused on content knowledge, organized the content largely by chronology, and

provided limited resources outside of the textbook. At the same time, her district had no required assessments in world history, so Talia was free to design

her own assessments, with the exception of one quarterly exam that she codesigned with her colleagues. She reported looking through the district curriculum

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

180

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

regularly to get a sense of what she should be teaching and to check her pacing.

Her assessments were typically quite traditional, including multiple-choice questions focused on factual recall. Gabrielles district curriculum focused on content

knowledge and historical thinking (specifically, a different way of thinking

each quarterperspective recognition and sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and researching questions). Her district organized the content around

larger themes and provided extensive resources, including primary documents and

graphic organizers. Gabrielles district had required unit exams for world history

that included multiple-choice questions, essays, and document analysis questions.

In interviews, she indicated that she used the district curriculum and assessments

in her planning, but she also generally agreed with the focus of the curriculum on

key themes in world history and historical thinking.

Teacher Education Context

Talia and Gabrielle graduated from the same masters certification program at

a state university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Both graduated from the same undergraduate institution in the spring of 2007. Gabrielle

majored in history and minored in Spanish; Talia majored in political science.

Gabrielle entered the program with a deep understanding of history as a discipline as well as world history topics in particular. Her student teaching placement

and first 2 years of teaching all focused on her area of expertise. In contrast,

Talias government major was not mirrored in the various courses she taught in

her first 3 years of classroom work: U.S. history, sociology, world history, and

psychology.

Gabrielle started the teacher education program in the summer of 2007. Talia

pursued an integrated teacher education route, taking four education courses

as an undergraduate and then joining the cohort in the fall of 2007. Together

Talia and Gabrielle took the second and third social studies methods courses

as well the courses Reading & Cognition, Diversity II, Action Research, and

Professionalism throughout the 20072008 academic year. Separately they took

Methods I, Adolescent Development, Content-Area Reading, and Diversity I

either during their undergraduate years (Talia) or during the summer of 2007

(Gabrielle). Talia and Gabrielle both completed a 1-year internship in a local

public school in the 20072008 academic year while taking these classes.

Talias first methods course covered a range of pedagogical methods for

teaching social studies, whereas Gabrielles first methods course focused on

understanding history as an inquiry-oriented, evidence-based discipline as well

as ways of representing history in the classroom. Talia and Gabrielle completed

the same methods courses in the fall and spring. Together these courses emphasized the teaching of historical understanding; specific strategies to teach reading,

discussion, and writing; curriculum development; assessment; and reflection and

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

181

revision. Assignments included asking a student to think aloud while reading

historical documents and interviewing him or her about the documents; creating

an inquiry-oriented lesson plan using historical sources for leading a discussion,

teaching reading, and teaching writing; teaching those lessons, reflecting on them,

and revising them; developing a curriculum unit; designing assessments; studying

an individuals learning during one unit of study; and studying a whole classs

learning during one unit of study.

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

Sources of Data

Data used in this article include observations of teaching, interviews with teachers, and classroom artifacts from the participants 3 years in the study. During

the preservice program, we observed each teacher three times at the beginning,

middle, and end of the school year. In the last 2 years of the study we observed

each teacher during two units of study each year after asking them to identify

units of study during which they would try to teach historical thinking, reading, or

writing. We define historical thinking broadly as the ways of thinking that often

accompany the interpretive work of historyconsidering cause and effect, recognizing multiple perspectives, situating events in historical context, analyzing

the affordances and constraints of historical sources, constructing evidence-based

arguments, or evaluating the merits of others claims. In the first year we observed

four to six classes per teacher for an average of 5.5 hr per teacher. In Year 2 we

observed three to five classes per teacher for an average of 4.5 hr per teacher.

After Year 1, we found that additional observations did not result in any new

information or data that challenged the patterns we had identified through analysis. Therefore, we observed less often in Year 2. Observations helped us see how

teachers represented the subject for students, how they scaffolded their instruction

and supported the development of students understanding, and how they reacted

to students ideas.

We collected artifacts of each teachers practices from the lessons observed

each year. Artifacts included readings, worksheets, lecture slides, assessments,

graphic organizers, and any other piece of paper or projection that teachers

shared with students during each unit. In addition, we collected students work

in response to assignments that the teacher identified as supporting students historical thinking, reading, or writing. The collection of artifacts aimed to capture

concrete examples of how teachers represented the subject, designed lessons, and

assessed students, as well as the resulting student work products. Artifacts also

helped us see what teachers did on days in the unit that we did not observe, giving

us some sense of how typical the days we observed were.

In the first year we interviewed each teacher six times, once at the beginning

of the year, briefly before each unit we observed, after each unit we observed,

and at the end of the school year. Setting up so many interview times proved

182

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

to be overly cumbersome to these novice teachers; therefore, in the second year

we interviewed teachers four times but spent longer with them after each unit.

In total, each year we interviewed each teacher for 5 hr. Interviews aimed to

gather evidence of teachers thinking about their pedagogical choices, history,

and their students. Interviews included analyzing students written work; charting a complete calendar of goals, activities, and assessments for each observed

unit; identifying salient influences on teachers practices; and probing teachers

instructional decision making.

Data Analysis

Throughout data collection, we analyzed observations, interviews, and artifacts

across all six participants in the larger study. Every 6 months we wrote comprehensive summaries and analytic memos. These initial analyses led us to identify

themes in novices teaching practice and thinking that highlighted their subject

matter knowledge and PCK for teaching history or government (e.g., theory of

how students learn, teacher thinking about student work or talk, attention to student thinking in the classroom, adjusting instruction to meet students needs,

vision for teaching history, conception of history, conceptualization of particular social studies topics, teaching history as evidence-based argument, teaching

history as information to recall). We applied these themes to interviews and observation notes in order to cluster the data and identify distinguishing patterns in

teachers practices, knowledge, and thinking (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Using

observation notes and artifacts of practice (e.g., readings, assignment sheets),

we created data matrices (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to display texts, activities, teacher questions, teacher talk, and time for each teachers units each year.

We organized these matrices chronologically and tabulated the amount of time

spent on different kinds of activities (Yin, 2003).

Because the topic of each unit remained the same for both teachers after

preservice, we looked specifically for any changes from year to year for each unit

of instruction. In tracking teachers PCK, we used the components of PCK found

in the literature as a framework for looking at the structure of their lessons, the

focus of the materials they gave to students, their thinking about or responsiveness

to students disciplinary thinking, and their conceptualization of the content and

how to make it accessible to students. We compared data displays and the changes

we identified to teachers interviews in order to understand the rationale, if any,

for the changes we noted in teachers practices. Based on these analyses we identified patterns in each teachers knowledge and practice as well as changes over

time. We then verified our conclusions about each teacher by checking for representativeness, triangulating across data sources, and looking for negative evidence

(Miles & Huberman, 1994). Finally, we compared the practices and thinking of

each teacher over time, using both data displays and clustered data, in order to

develop cross-case themes for discussion.

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

183

CASES OF DEVELOPING PCK FOR TEACHING HISTORY

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

Talia

In order to illustrate changes in her practice, we share lesson plans and thinking

from Talias methods coursework during her preservice year as well as our observations of lessons Talia taught in her first and second year after graduation. Talias

PCK was evident early in her methods coursework but was hidden in her first year

of teaching after her preservice program until it resurfaced, in part, in her second

year of teaching. Table 2 offers a visual summary of the PCK Talia demonstrated

over time.

Preservice Year. A government major, Talia taught U.S. history and sociology during her student teaching. Instead of a typical student teaching placement,

Talia was a paid intern at a local high school. This meant that before university

classes began in the fall, she was the teacher of record for three classes and had

to plan and teach every day without support or reprieve. In addition she had to

complete coursework for three university classes each semester. Although she had

a mentor teacher, Talia saw him primarily during her planning period because he

taught at the same time she did. In interviews she regularly reported feeling overwhelmed in the first semester of the preservice year and almost quit the program

because she did not feel she could do a good job in her coursework and her student teaching at the same time. Part of the challenge was the chaotic nature of

her school and her lack of experience with classroom management. We focus on

her lesson plans and thinking from her methods coursework and U.S. history field

placement.

TABLE 2

Where Talia Exhibited Particular Aspects of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Teaching

History Over Time

Talia

Preservice Program

Coursework

Interview

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Framing history

None observed

Classroom teaching

None observed

Year 1

Year 2

Not applicable

Not applicable

Attending to students

ideas about history

None observed

None observed

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

184

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Representing history. Talia constructed lessons for her methods course that

represented history in authentic ways, pairing analytical questions with relevant

documentary evidence. This interpretive approach to history came through in

a lesson on the causes of U.S. involvement in the Korean War that contrasted

speeches by President Truman with a textbook excerpt on the topic. In another

lesson, Talia compared a 1965 State Department paper with a 1971 John Kerry

speech (on behalf of Vietnam Veterans Against the War) to highlight the influence

of authors experiences and beliefs on their opinions about the Vietnam War. Her

lesson modeled the process of sourcing documents and the concept of perspective.

We never saw her teach either of these lessons; instead, the U.S. history classes we

observed included a lecture about the causes of imperialism and McCarthyism and

an analysis of a single document in each lesson to illustrate the ideas in the lecture.

Thus, the U.S. history classes we observed her teach during her preservice year

offered one way of interpreting these topics; in contrast, her methods coursework

offered multiple perspectives and opportunities for student inquiry.

Transforming history. Talia skillfully transformed history for students in her

methods coursework, and this knowledge became evident again during her second

year of full-time teaching. For her methods lesson plan on the causes of the Korean

War, Talia included a graphic organizer with prompts for students to consider

the author and date, causes suggested by the author, and specific evidence of the

causes in each document. She also shortened each document, adapted some of

the complex language, and added a head note to introduce each document. When

she practiced this lesson in her methods class, she did not model what to do with

the documents, but her reflection and revision included modeling how to use the

graphic organizer to guide students through the documents and to consider key

aspects of the documents. In her revision she also added a short background video

and map because she realized during the practice session that students might not

have the necessary background knowledge to make sense of the documents.

Attention to students ideas. Similarly, when prompted, Talia attended to

her students ideas, identifying their strengths and weaknesses and how she might

assist them. Talia explained that her students struggled with reading and analyzing documents. She told us, When they are looking at documents . . . they dont

understand who wrote it and why they wrote it and just take it for what it is.

They take it for fact. To assist her students, Talia told us that she developed a

rhythm for looking at documents. Always look at who wrote it and stop and

think how could that influence the document. Always look at the date. When was

that? Talia explained that she began to incorporate this type of guided practice

in her preservice year and felt that it improved students analysis of historical

documents. Despite demonstrating this ability to attend to student thinking in

interviews, Talia struggled with this in the classroom, where she regularly used

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

185

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

whole-class instruction. Classroom interactions often involved Talia presenting

information to students, asking questions about factual information, expecting

specific answers, and providing additional information and explanation. In these

cases, Talia typically did not probe students responses or ask follow-up questions.

Framing history. Talia also had difficulty applying her knowledge of how to

frame history, even though she framed history well for her methods coursework.

For her unit plan, Talia narrowed down a big topicthe civil rights movement of

the 1950s and 1960s in the United Statesto focus on why the movement was

successful. She organized days of instruction around four major concepts, all of

which led to the movements successes: organization, tactics, resources, and leaders. Each day of instruction focused on specific examples of one of these concepts,

and therefore each day linked to the overarching focus on why the movement

was successful. In planning this unit, Talia thought about how each day and topic

related to one another and excluded topics that did not fit with her framework

for the unit. In all, Talia demonstrated the four aspects of PCK we outline in her

methods coursework but had more difficulty putting this knowledge into practice

while student teaching.

Year 1 Teaching. Talia worked at a different school after graduation and

shifted to teaching U.S. and world history. She regularly reported feeling uncertain

and insecure this year, as in this interview excerpt: Honestly, I feel like I dont

know enough, Im still learning. I like to learn, but as Im learning, I dont know

if Im fit to teach all this stuff. In another interview she confessed, Im not very

animated and I dont seem too excited about it, because Im not that excited about

it . . . Im still trying to figure out what Im supposed to be doing in my life.

Here and in her second year we focus on lessons on the French Revolution

from her world history course, as this gave us a consistent focus in Years 1 and

2 (Talia stopped teaching U.S. history after Year 1). In her first year teaching full

time, we saw minimal evidence of the PCK she had demonstrated in her methods coursework. Her teaching that year mirrored her student teaching more than

her coursework. In her first year teaching, Talias students primarily experienced

lecture and textbook reading with questions.

Representing history. Talia represented history as fixed information and

presented the textbook, teachers notes, and primary documents as authoritative sources of the story students were to learn. For example, Talia opened the

first lesson on the French Revolution with a warm-up question that asked for

specific factual information (i.e., What are the three Estates?), followed by a

lecture focused on specific events leading up to the French Revolution. Talia used

PowerPoint for the lectures we observed in her first year and typed up the notes

as she shared them. Afterward students individually answered comprehension

186

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

questions about a political cartoon in the textbook and then listed causes of the

French Revolution using the textbook.

Transforming history. On the second day, Talia continued to represent history as fixed information and did not demonstrate the same level of skill in

transforming history. The lesson included a lecture about events during the French

Revolution, a primary account of the execution of Louis XVI, and a matching

exercise that paired terms with their appropriate descriptions. In introducing the

primary document, Talia reminded students to look at the source and date first,

but she never returned to this information as key to assessing the document as a

whole. Instead, the document was used at face value. After looking at the source

information, Talia asked her students to underline any reactions to the execution.

The reading (which focused on one persons reaction to Louis XVIs execution)

was more an enrichment activity that gave depth to the story they studied than an

activity that was centrally tied to the goals of the lesson or used for analysis. This

reading was a part of the ancillary material for the textbook, covered one entire

page with two columns of text, and included three questions focused on gathering

factual information (e.g., How did Louis XVI respond as he faced execution?).

Talia used historical documents sparingly during her first year of full-time teaching, and when she did, she offered little support for students to read successfully

or learn the skills of historical analysis.

Talias practices were consistent with her goals for this unit. At the end of this

unit, she shared the following:

I definitely wanted them to think about why the French Revolution could have

started. Mainly the causes and then analyze Napoleons role in that, his impact and

a lot of the ideas of the French Revolution like fraternity and liberty and all those

ideas that have to do with the Enlightenment so thats the major theme . . . But I

didnt think about I want them to be able to be better sourcers or contextualizers.

My main goal was to keep on using primary sources and have [students] be able to

break them down and understand them.

When asked why she valued primary sources, she said, Because the textbook

can be very dry and not offer students multiple perspectives. But she did not do

very much to support students analysis of primary sources because, she reported,

this unit was a little more makeshift. At the end of the first year she explained

that when she had used primary sources she had used them more like a textbook

than as an opportunity for analysis: I kind of deferred to using primary sources

for reading but not for researching or to take a step back and do the historical

thinking. We used it like a textbook reading, even though it was a primary source.

She cited a lack of planning time as the main cause and deplored her inability to

plan ahead and think through a unit of study before teaching it.

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

187

Attention to students ideas. Although Talia did not attend to students

ideas about history during our observations, she began to do so at the end of her

first year of teaching during interviews. In one lesson, Talia missed the opportunity to probe one students thinking and prior knowledge about King Louis

XVI and use it to get her students to think about Louis and the revolution more

deeply. As students were copying notes from a PowerPoint presentation and Talia

explained the information on the slides, one student said, I was reading his biography and he did try to help the people but he was a weak leader. Talia did not

respond to the student but moved to the next slide. However, when we asked Talia

to share her thinking about her students performance on an assessment, she noted

several weaknesses and said,

I dont understand because it seems so easy, but I guess its because its a rote memorization thing and they dont have a connection . . . If they read about the political,

social, and economic causes in the textbook they just have to memorize that, but if

they are figuring it out by looking at three primary sources, then they will learn it

more . . . I definitely would change a lot of things if I did it again.

In reflecting on student work she connected the kinds of activities they had

been engaged in to students performance and suggested an alternative that might

better support students learning. Talia began to connect student performance to

her teaching and thought about future changes she could make to improve their

work.

Framing history. Talia did not have an overarching goal or understanding

that she wanted students to learn in studying the French Revolution. Instead, as

each day focused on a different aspect of the French Revolution without clearly

connecting one day to another or connecting each day to an overarching idea.

Year 2 Teaching. Talia made a conscious decision during the summer after

Year 1 to develop her teaching and put in the effort she felt was required to teach

well. In the fall she said,

I made a decision earlier in the summer that I need to try to put more effort into

what Im doing and not just get like bogged down by the daily grind of things. If I

make time I can make it. It wont be perfect this year, I think it will take a few more

years to make it really nice. I wanted to try harder. I had to just sit down and make

that decision to be a teacher that works hard. . . . I think the whole [preservice and

first-year] experience was a whirlwind. I didnt value a lot of what we learned in

school because I was just trying to make it. . . . now that I was over all my issues

about insecurities in the classroom . . . I decided Im over that now and Im going to

tackle the strategies and focus on instruction, making it better, more coherent.

188

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

Although Talia felt that she had further to go in teaching history effectively, a

more positive attitude replaced the persistent doubts she had felt in her preservice

and first year. Talia reported fewer obstacles to teaching history and several

times remarked how motivating it was to have a student teacher that year. Talias

teaching was also more reminiscent of her methods coursework.

Representing and transforming history. The lessons we observed consistently represented history as an interpretive discipline rooted in analysis of

historical artifacts. In these lessons, Talia effectively transformed history by crafting materials and lessons that supported students as they learned the skills of

analysis. We observed the same French Revolution unit in Year 2 and report

comparisons here.

After asking students what might cause the French to overthrow an unjust government, Talia opened the French Revolution unit by saying, Were going to

try to figure out whats going on in France. She projected a picture of Marie

Antoinettes and Louis XVIs heads cut off and the warm-up question: Why

would people want to cut off their heads? She then gave a brief background

lecture about social class differences in pre-revolutionary France and analyzed a

political cartoon that characterized these differences together with the class (i.e., a

man labeled Third Estate carries men labeled First Estate and Second Estate

on his back). This was the same cartoon she used in the first year, but this time

instead of using textbook questions and individual work, Talia guided the class

to connect the cartoon to the background information on social class that she just

shared. She asked, Why is this old person who is representing the Third Estate

carrying A and B on his back? (A and B were the labels for the two other men

in the picture.) The majority of the lesson focused on understanding the causes of

the French Revolution using six documents and a graphic organizer. Talia modeled how to read and analyze one document together with students. She said, Ill

go through my thinking with you and you pay attention so you can do it on your

own. Then students worked in pairs, and finally they discussed their findings as a

class. The texts included two primary documents, one historians monograph, one

excerpt from the PBS website, and two textbook excerpts. The second day was

similar.

In her second year, Talia compiled primarily non-textbook readings in sets that

were thematically linked by an inquiry question (e.g., What caused the French to

overthrow their government?). She appeared to be less dependent on the textbook. Documents conveyed different perspectives or causes in response to an

inquiry question. Document analysis was more focused on historical concepts

such as causation or perspective than on mastering specific information. Students

spent the majority of their time on these activities in the first 2 days, and these document analysis activities appeared to address the main goals of each lesson. Talia

facilitated document analysis by modeling what she wanted students to do with

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

189

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

the documents and then guiding their analysis with specific prompts or questions.

The readings were all edited for length (i.e., each was one third to one fourth of

a page each) and for readability (i.e., Talia defined terms in parentheses such as

maxim [motto]). Talias warm-ups also focused more on ideas as well as on getting students thinking and interested (why . . . ) rather than asking informational

questions (what was . . . ).

Talia connected the idea of multiple documents with helping her students recognize historys interpretive nature and divergent perspectives on the past. In her

shift to teaching about perspectives and using multiple documents, she noted,

I think the documents, when I have more than one document, helps them see that I

can make an opinion out of this, oh there are different perspectives, its not just the

textbook. I can look at different perspectives and make a conclusion about it. Its not

set in stone. When I use the different documents they understand that.

She went on to connect why looking at the authorship of documents might help

her students understand the multiple causes of the French Revolution. She also

reflected on her work with documents as she looked at the artifacts from her Year

1 lessons and noted,

Im noticing also that usually in [Year 1] we only used one primary source document

for each day, so I actually remember thisthe execution of Louis and one primary

source. They arent really comparing anything and looking at different accounts of

what happened and reasons, they are just looking at one reason. And then it skips to

something else like a map analysis.

Not only could she see flaws in her teaching after Year 1, but she also had a clearer

vision for teaching history in Year 2.

Comparing Talias use of class time in Years 1 and 2 highlights the changes

in her representations and transformations of history. We found that of the days

we observed in Year 1, Talia spent 70 min on lecture, 62 min on reading, 77 min

on writing short answers or textbook-based worksheet responses, and 10 min on

warm-ups. In Year 2, however, Talia spent 20 min on lecture, 80 min on reading,

0 min on short answers or textbook-based worksheets, 15 min on writing extended

responses, 55 min on simulation, and 35 min on warm-ups. In other words, students spent more time actively working to make sense of the content with support

in Year 2 and less time passively receiving knowledge.

Attention to students ideas. Talia also demonstrated greater attention to

students ideas than in the first year. This type of responsiveness coincided with

her increased focus on historical thinking. On the last day of our observations,

Talia focused on Europe after Napoleon by giving groups time to prepare and

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

190

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

role-play one country in the process of creating a peace plan in a simulation about

the Congress of Vienna. Each group represented the perspective of one of the

countries at the Congress of Vienna, and as she walked from group to group,

we heard Talia say things like, But you are Prussia. What did Napoleon and

France do to you? Thats what you should think about and What would happen if you punished France too severely? She continued to encourage them to

think about the perspective of the country they represented and how what happened to them might influence what they wanted to happen as a result of the

Congress of Vienna. Instead of relying on students summaries of what happened

as she had in Year 1, she listened to students thinking and prompted them with

questions.

Framing history. Lastly, in Year 2 Talia framed the history presented within

each lesson more coherently, but she still did not frame history coherently across

lessons. Talia searched for documents from a wide range of sources and selected

documents that fit with her purposes on any given day. She had demonstrated this

skill in her preservice year but not in Year 1. This meant that in her second year,

each individual lesson was more coherent and centered on a specific goal, even if

the individual lessons taken together did not build to an overarching understanding. At the end of her preservice year she created a year-long plan for a U.S.

history course that focused on overarching objectives, including understanding

social change and recognizing multiple perspectives. By the end of her second

year, she had not developed similar overarching goals for world history.

Gabrielle

Gabrielles PCK grew in a more linear fashion. When we consider the context

of her learningincluding having a field placement that was aligned with the

focus of university coursework, having background knowledge in and teaching

world history only in her first 3 years, and remaining at the same school after

graduationthe consistent growth in her trajectory makes sense. Because aspects

of her PCK emerged in her preservice year and continued to be evident in subsequent years, we focus this section on establishing the PCK evident in her

preservice year and Year 1 and then sharing changes we noted in Year 2. Table 3

presents a visual summary of the PCK Gabrielle demonstrated over time.

Preservice Year. Gabrielle majored in European history and taught world

history throughout the time we observed her. Her student teaching was characterized by observation and periodic teaching in the fall followed by daily teaching in

the winter and spring. Her mentor encouraged her to use ideas from her methods

course in her student teaching and observed and gave feedback when Gabrielle

taught. Sometimes the mentor coached Gabrielle during the lesson, and other

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

191

TABLE 3

Where Gabrielle Exhibited Particular Aspects of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for

Teaching History Over Time

Gabrielle

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

Coursework

Interview

Classroom teaching

Preservice Program

Year 1

Year 2

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Framing history

None observed

Not applicable

Not applicable

Attending to students

ideas about history

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Framing history

Representing history

Transforming history

Attending to students

ideas about history

Framing history

times they debriefed after the lesson. There was a great deal of overlap between

Gabrielles field experience as a student teacher and her methods coursework.

Gabrielle used most of the assignments she created for her methods course.

Representing history. Gabrielle demonstrated her knowledge of content

and teaching from early in her preservice year and continued to do so through

her second year of teaching. For her first methods course lesson plan, Gabrielle

constructed a lesson using two primary sources to teach her students to contextualize evidence. She paired Martin Luthers 95 Theses with a report from an observer

of Johann Tetzel to get into the contemporary issue of selling indulgences (pardons for sins) as a motivation for Luthers protest. A central questionWhy did

Luther write the 95 Theses?anchored the lesson, which she used with her students. She crafted similar lessons for the remainder of her methods coursework

and continued to put many of them into practice.

Transforming history. Gabrielle modeled expert thinking with documents

during her preservice year. For example, she used the Luther text to help students

understand the widespread Church practice of selling indulgences that Luther so

vehemently opposed. While Gabrielle modeled sourcing as a reading strategy by

thinking aloud, she noted the authors word selection when she said, Eternally

damnedthat sounds seriouswhat does he mean? A student responded by

saying, He wants to be taken seriously. Gabrielle responded by reinforcing the

notion of understanding the authors interests when reading a text. She said, We

192

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

want to keep asking why, why, why is he saying this. Then she explicitly modeled

contextualization and guided students as they practiced with a second document.

Attention to students ideas. Although Gabrielle identified important

aspects of students thinking in course assignments, she inconsistently responded

to students thinking during the classes we observed. In one methods assignment,

Gabrielle asked a student to think aloud while reading two contrasting texts about

the Montgomery bus boycott. She noticed that her student did not understand that

the two documents presented two interpretations of the same event, nor did he

see that two different authors wrote these documents. In response to his reading,

Gabrielle devised an instructional plan to improve his historical analysis. During

one observation, Gabrielle discussed Martin Luthers 95 Theses with her students

and explained that Luthers language hints at his feelings about the Pope. She

pointed out his use of words and phrases like damned and burnt to ashes. Yet when

one of her students asked, So basically he was threatening the Pope? Gabrielle

moved on to the next part of her lesson without responding. During other lessons,

we observed Gabrielle respond to students ideas, but she tended to use stock

phrases such as How do you know? instead of responding more directly to the

content in students ideas.

Framing history. When Gabrielle wrote a unit plan on World War II for her

spring methods class, she struggled to adapt the districts curriculum to fit with

her goals and maintain a focus on developing students understanding of key ideas.

Her first draft included several lectures in a row without opportunities to process or

link information. She reported feeling that she needed to include so many lectures

because there would be no other way to cover the information specified in the

standards in such a short time. After some discussion and feedback, Gabrielle

found a way to organize the unit around key conceptual understandings such as

the roles of nationalism, economic crisis, and foreign policy in allowing Germany

to advance as far as it did. She began the unit with the Holocaust because she knew

her students were interested in the topic and had some background knowledge.

Then she organized the remainder of the unit around a series of inquiry activities

to help students develop an understanding of how such death and destruction came

to pass.

Year 1 Teaching. Gabrielle was fortunate to continue teaching the same

courses at the same school after she graduated. Her mentor, someone Gabrielle

valued and respected, also continued to work at the same school, and Gabrielle

regularly checked in with her for advice. In Years 1 and 2 we observed Gabrielle

teach a unit that included the French Revolution as well as other Atlantic

Revolutions. We report here on her approach to this unit in Year 1 and later

compare this to her approach to the same unit in Year 2.

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE FOR TEACHING HISTORY

193

Representing history. Gabrielles general approach to teaching history as

interpretation based on analysis of documentary evidence continued throughout

her first and second years as a full-time teacher. To kick off a lesson on absolutism in her first year, Gabrielle discussed a portrait of Louis XIV of France

and then walked through a speech by King James I to Parliament written in

1610. The ensuing discussion included the fact that the views of Parliament, as

well as the citizens of England, were missing, making the document limited as

a source for understanding the nature of absolutism. To compensate for this limitation, Gabrielle gave her students four other documents, each with additional

perspectives on absolutism. She then told her students that it was their turn to read

and annotate the documents. Then she asked students to compare this speech to

other documents from the time period that represented different perspectives on

absolutism. Students worked on documents in groups, and then they debriefed as

a whole class. Gabrielle brought the discussion to a close by explaining to the

students, What I want you to think about is that there might be some different

perspectives based on who you are. This lesson set the stage for an exploration

of the causes of the French Revolution.

Transforming history. During this lesson, Gabrielle modeled how to source

and recognize perspectives using the speech from King James I. She modeled

how to notice the author, audience, purpose, and missing perspectives evident in

the speech by asking questions aloud. Gabrielle directed her students attention to

the speech and asked, Who is this speech for? She then pointed to the source

attribution on the board, highlighted the word Parliament, and wrote audience

next to it. Gabrielle asked, What is the purpose of this document? Is it public or

private? Students responded that it would be public because it was delivered to

Parliament. She then proceeded to read the document aloud, stopping frequently

to highlight, underline, and circle words and phrases. She told students that they

should also identify words or ideas in the document that they found interesting,

that they had questions about, or that would help them understand the idea of an

absolute ruler. After the James I speech, Gabrielle gave her students repeated practice in recognizing perspectives, as that was a major focus for the unit. Gabrielles

documents were always shortened and sometimes modified to address students

literacy needs. She also regularly used guiding questions or graphic organizers to

direct students attention while reading. Gabrielle often asked students to work

in pairs and groups so that students had opportunities to share ideas and support

one anothers reading, but she did not always manage the groups or structure their

time together so that students could work productively together.

Attention to students ideas. In her first year of teaching, Gabrielle continued to recognize students thinking in their assignments and grew in her ability to

respond to their thinking in class. Gabrielle told us that one of her goals was for

her students to be able to recognize perspective and understand how an authors

Downloaded by [University of Nottingham] at 13:38 13 May 2013

194

MONTE-SANO AND BUDANO

perspective might influence his or her thinking. She explained that students were

still struggling with getting beyond identifying the author, and she shared an

example from a recent assessment. Students were given a document by Simon

Bolivar explaining his views about Spanish laws and were asked to explain how

his background may have influenced those views. The document included a head

note with information about Bolivar and his background. Gabrielle explained to

us that although most of her students were able to identify the author (Bolivar),

they had a difficult time explaining how his background may have played a part

in his assessment of Spanish laws. She noted that most students missed the fact

that he was an Enlightenment thinker and therefore would have viewed Spanish

laws through the lens of Enlightenment thinking. Some students did note, however, that he was of Creole descent and that this aspect of his background might

have influenced how he thought about Spanish laws. Gabrielle acknowledged that

these students were thinking in the right ways and that she could build upon that

type of thinking in order to help them understand perspective.

During class we observed Gabrielle challenge and explore students thinking most often when students analyzed historical documents in groups. When

Gabrielles students worked in groups to analyze documents, which occurred

almost every time we observed her class, she walked around the room and discussed students responses with them. She often asked questions like How do you

know? or What is your evidence for that? Because Gabrielle organized most

of her classes in pairs or small groups, she spent a lot of time circulating among

students. She typically listened to what students were saying and then responded

with general prompts to push students thinking or to redirect off-task behavior.

Framing history. Although perspective recognition was one piece of the

district-mandated assessment at the end of this unit, the final assessment also

focused on how global interaction changed the early modern world. As a result,

students were only partially prepared for the final unit assessment. Beyond