Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Discapacidad Intelectual DSM

Enviado por

Pamela HernandezDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Discapacidad Intelectual DSM

Enviado por

Pamela HernandezDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

AAIDD

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

To ID or Not to ID? Changes in Classification Rates of

Intellectual Disability Using DSM-5

Aimilia Papazoglou, Lisa A. Jacobson, Marie McCabe, Walter Kaufmann, and T. Andrew Zabel

Abstract

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersFifth Edition (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria

for intellectual disability (ID) include a change to the definition of adaptive impairment. New

criteria require impairment in one adaptive domain rather than two or more skill areas. The authors

examined the diagnostic implications of using a popular adaptive skill inventory, the Adaptive

Behavior Assessment SystemSecond Edition, with 884 clinically referred children (ages 616).

One hundred sixty-six children met DSM-IV-TR criteria for ID; significantly fewer (n 5 151,

p 5 .001) met ID criteria under DSM-5 (9% decrease). Implementation of DSM-5 criteria for ID

may substantively change the rate of ID diagnosis. These findings highlight the need for a

combination of psychometric assessment and clinical judgment when implementing the adaptive

deficits component of the DSM-5 criteria for ID diagnosis.

Key Words: adaptive functioning; intellectual disability; mental retardation; DSM-IV; prevalence

The diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID; formerly

known as mental retardation) is characterized by

concurrent deficits in intellectual and adaptive

functioning, with onset prior to adulthood. Prevalence rates for ID are generally estimated to be 1% of

the population, with higher rates in middle and lowincome countries (Maulik, Mascarenhas, Mathers,

Dua, & Saxena, 2011). In the United States, this

amounts to approximately 3 million people (Larson

et al., 2001), with more than 543,000 children (ages

621) identified by the public school system as having

some level of ID (U.S. Department of Education,

2007). A diagnosis of ID has a number of important

implications, including eligibility for supports such as

academic services, residential placement, vocational

support, and Social Security Disability, as well as

ineligibility for capital punishment.

The definition of ID has undergone many

revisions. Initially, ID referred only to impairments

in intellectual functioning; however, in 1959,

impairments in age-appropriate day-to-day functioning (adaptive functioning) formally became part of

the definition (Heber, 1959, 1961). More recent

diagnostic formulations of ID have maintained the

requirements for deficits in both intellectual ability

and adaptive functioning. In the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersFourth Edition

A. Papazoglou et al.

(Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR), the intellectual

impairment component of the diagnosis of ID

was defined as significantly subaverage intellectual

functioning: an IQ of approximately 70 or below

(American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p. 49).

Based largely upon the definition of adaptive

functioning proposed by the American Association

of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

(AAIDD, formerly known as the American Association on Mental Retardation; Luckasson et al.,

1992), DSM-IV-TR defined adaptive functioning

deficits as concurrent impairments (e.g., performance approximately 2 standard deviations [SD]

below the mean) in at least two theoretically derived

adaptive skill areas (i.e., communication, self-care,

home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic

skills, work, leisure, health, and safety; American

Psychiatric Association, 2000). Of note, there is

some debate about whether there are 10 or 11

adaptive skill areas depending on whether or not

health and safety are considered distinct skill areas.

Subsequently, broader factors or adaptive domains

composed of these individual adaptive skill areas

were described (e.g., Greenspan, 1999; Harrison &

Oakland, 2003; Luckasson et al., 2002; Thompson,

McGrew, & Bruininks, 1999). These three broad

165

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

domains (i.e., Conceptual, Social, Practical) have

since been incorporated into the AAIDD description of adaptive functioning (Luckasson et al., 2002;

Schalock et al., 2010).

The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5; American

Psychiatric Association, 2013) includes a change in

the name of the disorder, a revision of the diagnostic

criteria, and changes in the severity specifiers.

Consistent with the AAIDDs and the international

communitys shift from the term mental retardation to

intellectual disability, DSM-5 uses the term intellectual

disability coupled with the term intellectual developmental disorder (to be consistent with International

Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition). As was the case

with DSM-IV, DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ID

specify evidence of intellectual and adaptive impairment during the developmental period. DSM-5

criteria pertaining to intellectual impairment are

similar to those of DSM-IV and stipulate deficits in

general mental abilities such as reasoning, problemsolving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience,

defined as an IQ of approximately # 70 (6 5 points

for error; American Psychiatric Association, 2013,

p. 37). The DSM-5 criteria pertaining to deficits in

adaptive functioning, however, have been more

significantly modified. Specifically, adaptive impairment is defined as follows (American Psychiatric

Association, 2013):

Deficits that result in failure to meet

developmental and sociocultural standards for

personal independence and social responsibility (p. 33).[The criterion] is met when at

least one domain of adaptive functioning

conceptual, social, or practicalis sufficiently

impaired that ongoing support is needed in

order for the person to perform adequately in

one or more life settings at school, work, home

or in the community. (p. 38)

In contrast to DSM-IV, which stipulated impairments in two or more skill areas, DSM-5 criteria

denote impairment in one or more superordinate

domains of adaptive functioning (e.g., Conceptual,

Social, Practical).

DSM-5 also redefines how ID severity is

determined. DSM-IV-TR defined severity on the

basis of IQ test scores (mild, moderate, severe,

or profound). These same levels of severity are

retained; however, in DSM-5 the various levels of

severity are defined on the basis of adaptive

166

AAIDD

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

functioning, and not IQ scores, because it is

adaptive functioning that determines the level of

supports required. Moreover IQ measures are less

valid in the lower end of the IQ range (American

Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 33).

For diagnostic purposes under DSM-5, deficits

in adaptive functioning are still established by way

of clinical evaluation and administration of psychometrically sound measures, such as questionnaires that elicit observer or informant ratings of an

individuals typical level of independent functioning (McCarver & Campbell, 1987). Of note,

however, DSM-5 provides a table offering additional guidance for determining severity of adaptive

impairment (i.e., mild, moderate, severe, and

profound) within Conceptual, Social, and Practical

domains. This table is intended to assist in

determination of severity of adaptive impairment,

although no specific guidance is given regarding the

use of test scores for the determination of severity

specifiers (e.g., the mild range of ID is not defined

by a test score range). Clinicians are encouraged to

use both clinic evaluation and individualized,

culturally appropriate, psychometrically sound measures (American Psychiatric Association, 2013,

p. 37), and to use clinical judgment when interpreting scores from these measures.

One such standardized observerinformant

report instrument is the Adaptive Behavior Assessment SystemSecond Edition (ABAS-II; Harrison

& Oakland, 2003), which is a commonly used

measure of adaptive functioning on which a

caregiver rates the individuals level of independent

functioning on multiple items across skill areas.

The parent form is used for children ages 521 years

and provides estimates of the childs functioning

across 9 skill areas (or 10 skill areas if he or she is

employed). Scale composition of the first edition of

the ABAS (Harrison & Oakland, 2000) was

substantively influenced by the definition of

adaptive functioning proposed by the AAIDD and

others (e.g., Luckasson et al., 1992; Thompson

et al., 1999), as well as the diagnostic criteria in

DSM-IV. The skill areas were maintained in the

publication of the second edition (ABAS-II;

Harrison & Oakland, 2003), but in keeping with

the existing body of research (e.g., Greenspan,

1999; Harrison & Oakland, 2003; Luckasson et al.,

2002; Thompson et al., 1999) and the revised ID

conceptualization proposed by the AAIDD, these

skill areas were further organized into three broad

adaptive skill domains: Conceptual, Practical, and

Intellectual Disability and DSM-5

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

AAIDD

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

Social. The ABAS-II domains have increased

relevance with the publication of DSM-5, as they

map onto the new adaptive domain model

presented in DSM-5. Of note, the ABAS-II

groupings of the individual skill areas into domain

scales were modeled on theoretical foundations

based in earlier research, and were not based on

exploratory factor loadings. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis of the ABAS-II has yielded

only modest support for this three-factor model

(Wei, Oakland, & Algina, 2008), and there is

evidence to suggest that the most parsimonious fit

to the data is a one-factor solution (Harrison &

Oakland, 2003). To date, there has been little

research on the appropriateness of the 9 and 10 skill

area factors.

The aim of this study was to examine the

potential impact of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria

on classification rates of ID. There is the potential

for a gray zone in which individuals meet ID

criteria under the DSM-IV-TR criteria (i.e., impairment in two or more skill areas) but not under

DSM-5 criteria (i.e., impairment in one or more

domains), particularly when psychometric measures

such as the ABAS-II are used as the primary means

to quantify deficits in adaptive functioning. For

instance, under the ABAS-II factor structure,

individuals with skill deficits in home living and

self-care might still qualify for ID, as both of these

skills are grouped under the Practical domain

factor. In contrast, an individual with skill deficits

in social skills and functional communication

might not, as these skill areas are grouped into

different domain factors. Clarification of a possible

diagnostic drift in ID diagnoses is valuable, as the

implications for the educational (i.e., eligibility for

special education services), social (i.e., eligibility

for entitlement services and funding), and legal

(i.e., capital punishment decisions) systems may be

profound. To this end, we examined ID classification rates using a psychometric definition of

impairment as two or more skill areas (DSM-IVTR criteria) and one domain area (DSM-5 criteria),

with adaptive impairment defined as standardized

scores $ 2 SD below the mean. Given persistent

questions about the factor structure of the ABASII, we hypothesized that, when compared with

classification rates of ID using DSM-IV-TR criteria,

diagnosis based on psychometrically defined impairment in one domain (DSM-5 criteria) has the

potential to result in significantly fewer children

meeting criteria for ID.

A. Papazoglou et al.

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

Methods

Participants

For the purposes of this study, de-identified patient

records from the clinical database of the Department of Neuropsychology at the Kennedy Krieger

Institute, a large medical institute serving youth

with developmental disabilities in the mid-Atlantic

region, were reviewed. Data are routinely entered

into this database by department clinicians via the

electronic health record, and are securely maintained by the information systems department.

After approval by the Johns Hopkins Hospital

institutional review board, a limited dataset was

constructed of patients between the ages of 6 and

16 years for whom valid scores on both intellectual

(e.g., Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children

Fourth Edition, WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003) and

adaptive (e.g., ABAS-II; Harrison & Oakland,

2003) measures were available. The final sample

included 884 children (mean age 5 10.49, SD 5

2.80; 67% male), for whom records included

WISC-IV and ABAS-II scores, age at time of

assessment, ethnicity, and sex. All patients included in the dataset had been referred for outpatient

neuropsychological assessment. Of these 884 children and adolescents, 203 had a Full Scale IQ

(FSIQ) that was $ 2 SD below the mean (FSIQ #

70), representing 23% of the total clinically

referred sample.

Measures

ABAS-II. The ABAS-II is a parent-report

questionnaire assessing whether an individual

independently displays the functional skills necessary for age-appropriate daily living. The ABAS-II

divides adaptive functioning into nine skill areas,

which are subsumed under three theoretically

derived domains: the Conceptual Domain (Communication, Functional Academics, and Self-Direction skill areas), Social Domain (Leisure and

Social skill areas), and Practical Domain (Community Use, Home Living, Health and Safety, and

Self-Care skill areas). A 10th skill area, Work skills,

can be administered to older adolescents and young

adults who are employed, but it was not included in

this study given the age range of the sample. The

nine primary skill areas can be used to generate a

General Adaptive Composite (GAC). As noted in

the test manual (Harrison & Oakland, 2003), the

ABAS-II GAC has strong internal consistency

(a 5 .98) as do the domain (a 5 .86.93) and skill

167

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

AAIDD

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

area scores (a 5 .95.97). Stability over time (M 5

12 days, SD 5 10 days) is strong (GAC corrected

testretest reliability r 5 .93, domain corrected

testretest r 5 .89.93, skill area corrected test

retest r 5 .84.92). The ABAS-II also has

demonstrated adequate validity in a sample of

children with ID (e.g., mean GAC scores in a group

of 41 individuals between the ages of 5 and 21

diagnosed with ID, of unspecified severity, was

equal to 63.7, mean skill area scaled scores ranged

from 3.7 to 5.5). Of note, 82.93% of these

individuals with ID had two or more individual

skill area scores that fell at or below 22 SD, while

80.49% of these same individuals had one or more

adaptive domain scores that fell at or below 22 SD

based on caregiver report. Because the sample is

described as unspecified, there is no way to

examine these data at various levels of intellectual

impairment (e.g., mild versus moderate intellectual

ability). However, although statistical significance

was not reported, there was a trend toward a higher

percentage of impaired skill area scores reported for

individuals with mild ID in the validity data for the

teacher version of the ABAS-II. Specifically, of the

66 individuals with mild ID who were rated by their

teachers on the ABAS-II, 75.76% had two or more

individual skill areas scores that fell at or below 22

SD, while only 60.61% of these same individuals

had one or more adaptive domain scores that fell at

or below 22 SD (Harrison & Oakland, 2003).

Two other commonly used measures of adaptive functioning are the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II; Sparrow,

Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) and the Scales of

Independent Behavior, Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks,

Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996). Correlations between the ABAS-II GAC and VABS-II

Adaptive Behavior Composite were moderately

high (r 5 .78), with correlations at the subdomain/skill area level mostly falling in the 0.50

range. Correlations between the ABAS-II GAC

parent version and the Early Development Form of

the SIB-R Broad Independence Score were low (r

5 .18), while the correlation between the ABAS-II

GAC teacher-version and the Short Form of the

SIB-R Broad Independence Score were stronger

(r 5 .59).

WISC-IV. The WISC-IV is a widely accepted

measure of intellectual ability with adequate

psychometric properties for identifying children

with ID. The WISC-IV provides a global intellectual estimate, the FSIQ. The FSIQ has shown

168

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

excellent internal reliability and stability over time

(e.g., internal consistency estimates [split-half]

yield an FSIQ r 5 .97; corrected testretest r 5

.93). The WISC-IV FSIQ also has demonstrated

adequate validity for use with this population

(Wechsler, 2003).

Experimental Design

First, we examined the pattern of associations

between measures of intellectual and adaptive skill

areas. Next, the total number of children who met

strict DSM-IV-TR criteria for ID was identified

(i.e., WISC-IV FSIQ # 70, with two or more skill

areas on the ABAS-II # scaled score of 4). The

total number of children who met the psychometrically defined DSM-5 criteria was then calculated

(i.e., WISC-IV FSIQ # 70, with one or more

domains on the ABAS-II # 70). The McNemar

test was used to compare the differences in the

proportion of individuals classified as ID based on

the changing criteria for adaptive impairment.

Results

Of the 203 children with FSIQ # 70, 166 met

DSM-IV-TR criteria for adaptive impairment, that

is, impairment in two or more skill areas. On the

basis of DSM-5 criteria for adaptive impairment

(i.e., impairment in one or more adaptive domains),

151 children met criteria for ID. This represents a

net loss of 15 children. Sixteen children met DSMIV-TR criteria but not DSM-5 criteria, and one

child met DSM-5 criteria but did not meet DSMIV-TR criteria. This net difference of 15 children

represents a statistically significant 9% decrease in

the number of children who met criteria for ID

under DSM-5 as compared to DSM-IV-TR (McNemar test x2 5 122.02, p 5 .001). Mean scores on

the ABAS-II and WISC-IV for the children who

meet DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 criteria for adaptive

impairment are presented in Table 1.

In the total clinically referred sample (N 5

884), there was a broad range of correlations

between FSIQ and individual skill areas on the

ABAS-II. The strongest correlations were noted

between FSIQ and the ABAS-II Functional

Academics (r 5 .56, p , .001) and Communication (r 5 .39, p , .001) skill area scales. All of the

remaining seven ABAS-II skill area scales also were

significantly correlated with FSIQ (p , .001), with

correlations ranging from r 5 .13 to r 5 .32. Each

of the composite domain scales of the ABAS-II was

Intellectual Disability and DSM-5

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

AAIDD

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

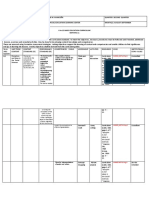

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

Variable

Age in years

Percent male

Percent White: African American:

Other: Unknown

WISC-IV FSIQ

ABAS-II GAC

ABAS-II Conceptual

ABAS-II Social

ABAS-II Practical

All children with

FSIQ # 70

(n 5 203)

DSM-IV: FSIQ and

two skill areas impaired

(n 5 166)

DSM-5: FSIQ and

one domain impaired

(n 5 151)

11.32 (2.73)

66

11.35 (2.69)

67

11.38 (2.71)

68

37: 42: 6: 15

60.25 (7.79)

66.22 (15.21)

68.88 (13.74)

74.82 (15.63)

66.22 (15.22)

38: 41: 7: 14

59.49 (8.06)

61.10 (10.67)

64.82 (10.42)

70.36 (12.44)

60.43 (15.27)

40: 38: 7: 15

59.15 (8.21)

59.28 (9.23)

63.15 (9.30)

68.58 (11.10)

58.20 (14.26)

Note. Standard deviations are presented in parentheses. ABAS-II and WISC-IV scores are presented as standard

scores.

significantly correlated with FSIQ (all p , .001),

with the strongest correlations noted with the

Conceptual domain (r 5 .48) as compared to the

Social (r 5 .31) and Practical (r 5 .32) domains. In

children with FSIQ # 70, the frequency of

impaired scores (i.e., scaled score # 4) on the

ABAS-II skill area scales was as follows: Home

Living (70%), Self-Direction (68%), Social (66%),

Functional Academics (58%), Self-Care (56%),

Community Use (51%), Communication (46%),

Health and Safety (45%), and Leisure (35%). In

this group, impaired domain scores (standard scores

# 70) were most frequently found on the

Conceptual (62%) and Practical (62%) composites

and were less frequently observed on the Social

composite (48%).

Data on the 17 children whose status changed

with the shift to DSM-5 criteria are presented in

Table 2. Bold font is used to denote children who

were impaired in ABAS-II skill areas. The one

child who met DSM-5, but not DSM-IV, criteria

was impaired on the Conceptual domain and had a

single area of skill area impairment (Communication), with three other skill areas in the borderlineimpaired range. Of the 16 children who met DSMIV, but not DSM-5, criteria, 100% had a FSIQ of

# 70, 25% had a Verbal Comprehension Index of

# 70, 38% had a Perceptual Reasoning Index of

# 70, 81% had a Working Memory Index of # 70,

and 88% had a Processing Speed Index of # 70.

The majority of these children had two skill areas

impaired (69%), with 19% impaired on three skill

areas, and 12% impaired on four skill areas. Home

A. Papazoglou et al.

Living was most likely to be impaired (56%),

followed by Communication (38%), Functional

Academics (38%), Self-Care (31%), Social (31%),

Self-Direction (19%), Community Use (19%), and

Health & Safety (12%). No children were impaired

on Leisure.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate any potential

impact on the rates of ID classification when an

existing and widely used adaptive functioning

measure (ABAS-II) was used to psychometrically

determine deficits in adaptive functioning based on

implementation of the new DSM-5 ID criteria. The

DSM-5s use of adaptive impairment to quantify

severity of ID highlights a renewed emphasis on

adaptive functioning in this condition. There is

concern, however, that the diagnostic change from

adaptive skill deficits to adaptive domain deficits

might make the diagnosis more restrictive due to

instrumentation and measurement issues, particularly when psychometric measures are used as the

primary means to quantify deficits in adaptive

functioning. We hypothesized that, when using the

ABAS-II to psychometrically quantify adaptive

impairment, fewer children would qualify for an

ID diagnosis when DSM-5 criteria were implemented (relative to DSM-IV). This was supported, as we

identified a potential 9% decline in the number of

children who met criteria for DSM-5 as compared

with DSM-IV-TR in our large clinical sample. Of

note, the children excluded by DSM-5 ID criteria

had milder degrees of adaptive impairment,

169

170

67

65

54

67

68

56

59

70

70

56

64

61

60

52

69

55

13.75

13.17

14.58

14.33

8.75

12.58

11.42

8.5

11.42

8.42

10.67

7.92

7.42

8.42

12.67

13.08

89

83

73

79

69

75

79

73

89

59

79

75

65

57

77

77

57

73

75

57

73

88

55

57

71

73

73

61

73

71

61

86

51

59

75

79

82

88

69

85

84

77

84

76

85

80

82

69

70

82

78

Does not meet ID criteria for DSM-IV, but does meet criteria for DSM-5

67

84

87

2

7

5

6

Meet criteria for ID on DSM-IV-TR but not on DSM-5

72

90

79

6

6

5

5

75

90

82

9

8

6

5

78

97

81

7

7

6

3

91

100

83

10

11

9

3

72

81

75

6

8

1

2

86

92

87

8

6

4

3

87

93

82

13

7

4

4

88

72

79

9

7

7

4

72

105

86

7

10

6

1

81

96

72

3

6

5

2

80

97

87

4

10

6

4

83

87

85

3

2

9

11

81

72

95

4

9

7

8

75

72

78

3

7

3

6

72

78

78

2

4

4

6

80

93

82

9

1

4

8

7

10

11

10

6

11

9

6

7

3

9

7

11

4

5

7

11

6

8

10

10

7

7

8

5

12

8

10

10

6

5

9

6

2

3

4

3

4

8

6

6

11

8

8

7

7

5

6

10

4

1

9

6

6

9

5

7

2

9

8

5

5

8

9

5

9

7

9

11

5

9

10

4

10

10

9

4

3

4

2

11

Health

Communi- Functional Home and

Self- Self-Dication Use Academics Living Safety Leisure Care rection Social

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

Note. Boldface indicates children with impairment on the same skill area of the ABAS-II. WISC-IV and ABAS-II GAC and domain scores are presented as

standard scores, ABAS-II skill area scores are presented as scaled scores. Abbreviation: VCI, Verbal Comprehension Index; PRI, Perceptual Reasoning

Index.

50

10.92

Age WISC-IV

ABAS-II

Commu(years) FSIQ

VCI PRI GAC Conceptual Social Practical nication

Table 2

Standardized Scores on the ABAS-II and WISC-IV for Children Whose ID Diagnostic Classification Changes With the Implementation of DSM-5 Criteria

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

AAIDD

Intellectual Disability and DSM-5

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

although their profiles still indicated a high level of

adaptive and intellectual impairment. Given the

relatively mild nature of their adaptive impairment,

it is unclear whether these children and adolescents

would have been identified with ID during the

DSM-IV-TR era, even though their IQ and ABASII scores were consistent with the diagnostic

criteria. As such, these data are of somewhat

limited value in anticipating the true impact of

DSM-5 on rates of ID. What these data do

highlight, however, is the need for clinical

judgment when interpreting these scores, rather

than a strict reliance upon scores from the current

psychometric scale compositions.

When adaptive impairment is psychometrically

defined using ABAS-II scores, the children in our

sample who would be left out of an ID diagnosis

by the impaired domain criterion still show

compelling evidence of intellectual and adaptive

skill impairment. Among the children left out of

the DSM-5 ID classification, their various combinations of adaptive skill area deficits tended to load

onto different domains (rather than a single

domain), resulting in domain level scores that were

above a standard score of 70 in spite of the presence

of impairment in multiple skill areas. For instance,

a child with skill area deficits in Communication,

Social skills, and Community Use may experience

significant adaptive impairment, even though each

of these skill areas is grouped onto separate ABASII domains and these composite scores may fall

within normal limits. Analysis of adaptive functioning in the 16 children who would be excluded

from an ID diagnosis based on DSM-5 criteria

revealed that Home Living was the most commonly

impaired skill area, followed by Communication,

Functional Academics, Self-Care, and Social skills.

These skill areas span all three of the ABAS-II

adaptive domains, and highlight the manner in

which significant skill area deficits may be hidden

by grossly intact domain scores.

Given the common assumption that intellectual deficits contribute to deficits in adaptive skills

in youths with ID, it is not unexpected that

intellectual and adaptive functioning would be

significantly correlated. From a measurement

perspective, however, it remains unclear whether

a low score in an adaptive area that is highly

correlated with IQ constitutes a distinct area of

adaptive deficit related to IQ rather than simply a

multimethod approach to measuring the same

construct. This has, in fact, been a criticism of

A. Papazoglou et al.

AAIDD

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

the formulation of the diagnosis of ID in the past,

as Greenspan (2006) and others have proposed

that the Conceptual composite of the ABAS-II

and its constituent skill area scales may measure

much the same construct as an IQ test (i.e.,

conceptual or academic intelligence). Indeed, in

our sample of children with a FSIQ of # 70, IQ

was most highly correlated with the Conceptual

domain (r 5 .30, p , .001), with smaller, albeit

still significant, correlations with the Practical

(r 5 .27, p , .001) and Social (r 5 .18, p , .001)

domains. As noted, the degree of variation in

correlation between IQ and adaptive domain

scores not only raises a concern regarding multimethod assessment of the same construct (e.g., IQ

and Conceptual adaptive functioning), but also

raises a question as to the relatedness of IQ and

adaptive functioning in general. While each

ABAS-II adaptive domain was significantly correlated with IQ, the varying degrees of correlation

between IQ and the three adaptive domains brings

into question the idea of a direct relationship,

which is presumed in the ID diagnosis (i.e., To

meet diagnostic criteria for intellectual disability,

the deficits in adaptive functioning must be

directly related to the intellectual impairments,

American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 38).

Future conceptualizations of ID may benefit

from further shifting the diagnostic emphasis to

deficits in adaptive functioning, as this might better

define a subgroup of individuals who are highly

vulnerable to exploitation or injury and require

additional protections (regardless of IQ). Barkley

and colleagues have proposed the concept of

adaptive disability, in which deficits in adaptive

functioning are associated with behavioral factors

(e.g., conduct problems, inattention, aggression)

within the context of broadly intact intelligence

(Barkley et al., 2002; Shelton et al., 1998). Other

recent work has identified relatively distinct

cognitivebehavioral clusters associated with deficits in adaptive functioning, with IQ representing

only one of many variables thought to contribute to

deficits in adaptive functioning (Papazoglou, Jacobson, & Zabel, 2013a). We propose that future

DSM revisions consider the evidence for the

concept of an adaptive disability in which deficits

in adaptive functioning are the primary diagnostic

feature, with associated specifiers to qualify presumed etiologies (e.g., with intellectual deficits,

with executive functioning deficits, with affective

dysregulation, etc.).

171

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

In closing, we strongly recommend that

discussion concerning the impact of new DSM-5

ID diagnostic criteria include discussion of practical

assessment issues that may occur when new

diagnostic criteria are implemented using existing

test instruments such as the ABAS-II. First,

although existing adaptive skill instruments have

been shown to be reliable, it is very important that

the underlying construction of the tests be considered when they are applied to new diagnostic

formulations. As noted earlier, the domain factor

structure of the ABAS-II was organized on the basis

of theoretical foundations, and the model then

underwent confirmatory factor analysis. Although

this is an appropriate method for test construction,

it may not capture the strongest factor loadings or

provide information about other potential arrangements of the scales. Subsequently, individual

adaptive skill area deficits may be somewhat

silenced in the larger factor model. As such, the

diagnostic utility of existing adaptive skill instruments such as ABAS-II should be explored before

presuming that they are equally valid under both

DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 conditions, and clinical

judgment should continue to be emphasized in the

diagnostic process to help minimize possible

psychometric measurement issues. Moreover, agreement between different measures should be explored, as quantification of deficits in adaptive

functioning can vary considerably between instruments (Papazoglou, Jacobson, & Zabel, 2013b) and

further complicate the diagnostic picture. To

mitigate the potential impact of these issues,

DSM-5 recommends that the clinician use multiple

sources of information as well as clinical judgment

when establishing whether an individual presents

with significant deficits in adaptive behavior.

In addition, we recommend that the appropriateness of content from current adaptive skill

instruments be reviewed, particularly given the

renewed emphasis placed on adaptive impairment

in the DSM-5 ID diagnostic formulation. Due to the

pace of accommodative technology, the definition of

an adaptive deficit is likely to continue to change

rapidly. Although the advent of GPS guidance

systems, text-to-speech software, smart phones,

electronic cueing devices, and other technologies

has created exciting new habilitation opportunities,

the speed with which these devices become available

outpaces the more time-intensive process necessary

for the development and standardization of adaptive

skill measures. This dilemma will likely continue,

172

AAIDD

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

creating a disparity between the reality of the

individuals situation (e.g., ability to use a smart

phone and access the Internet) and the content of

the latest version of a standardized adaptive skill

instrument (e.g., ability to use a pay phone and read

a newspaper). Lack of items reflecting an individuals

ability to use technologies such as a smart phone, a

computer, and the Internet creates both face validity

and content validity questions, particularly as these

types of technologies continue to become normal,

necessary components of daily living rather than

accommodative technologies or interventions. This

is a particularly salient dilemma for the ABAS-II,

which contains the same item content from the

original ABAS, which was developed prior to the

collection of standardization data between December 1998 and December 1999.

Although these findings have important implications for clinical practice and policy, this study

has several limitations. All children were clinically

referred, so results may not be consistent with

potential findings in a nonreferred population,

although it is worth noting that the decisionmaking process regarding classification of ID is

inherently a clinical one. More specifically, however, the Kennedy Krieger Institute is an internationally recognized center of excellence for children

with developmental disabilities, thus the population

of children referred for evaluation here may be more

significantly impaired than those for whom ID

classification decisions are made in other settings

(e.g., local school special education decisions). If this

is indeed the case, the measurement issues raised

concerning the ABAS-II skill area and adaptive

domain scores may be overrepresented or underrepresented. More research is needed regarding the

factor structure of the ABAS-II and whether the 9

and 10 skill areas and three domains represent

appropriate factor groupings of the ABAS-II items.

Research to date has shown only modest support for

the three domains (Wei et al., 2008), and there are

limited data on the 9-and-10 factor solutions. No

data were available regarding whether clinicians

actually made a diagnosis of ID for all 166 children

who met formal DSM-IV-TR criteria, and, to our

knowledge, there are no published data examining

how consistently clinicians adhered to DSM-IV-TR

diagnostic criteria when making a diagnosis of ID.

Nevertheless, these findings suggest a risk of fewer ID

diagnoses when existing adaptive functioning instruments are used as the primary means by which to

implement DSM-5 criteria for adaptive impairment.

Intellectual Disability and DSM-5

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(4th ed., text rev). Arlington, VA: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barkley, R. A., Shelton, T. L., Crosswait, C.,

Moorehouse, M., Fletcher, K., Barrett, S., &

Metevia, L. (2002). Preschool children with

disruptive behavior: Three-year outcome as a

function of adaptive disability. Developmental

Psychopathology, 14, 4567.

Bruininks, R. H., Woodcock, R. W., Weatherman,

R. F., & Hill, B. K. (1996). Scales of Independent

Behavior-Revised. Chicago, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Greenspan, S. (1999). A contextualist perspective

on adaptive behavior. In R. L. Schalock (Ed.),

Adaptive behavior and its measurement: Implications for the field of mental retardation (pp. 61

80). Washington, DC: American Association

on Mental Retardation.

Greenspan, S. (2006). Mental retardation in the real

world: Why the AAMR definition is not there

yet. In H. N. Switzky & S. Greenspan (Eds.),

What is mental retardation? Ideas for an evolving

disability in the 21st century (pp. 167185).

Washington DC: American Association on

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Harrison, P., & Oakland, T. (2000). Adaptive

behavior assessment system. San Antonio, TX:

The Psychological Corporation.

Harrison, P., & Oakland, T. (2003). Adaptive

behavior assessment system (2nd ed.). San

Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Heber, R. (1959). A manual on terminology and

classification in mental retardation: A monograph supplement. American Journal of Mental

Deficiency (Monograph Supplement), 64, 1111.

Heber, R. (1961). A manual on terminology and

classification in mental retardation (rev. ed.).

Washington, DC: American Association on

Mental Deficiency.

Larson, S. A., Lakin, K. C., Anderson, L., Kwak, N.,

Lee, J. H., & Anderson, D. (2001). Prevalence

of mental retardation and developmental disabilities: Estimates from 1994/1995 National

Health Survey Disability Supplement. American

Journal of Mental Retardation, 106, 231252.

Luckasson, R., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Buntinx,

W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. M., Reeve,

A. Papazoglou et al.

AAIDD

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

A.,Tasse, M. J. (2002). Mental retardation:

Definition, classification, and systems of supports

(10th ed.). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Luckasson, R., Coulter, D. L., Polloway, E. A.,

Reiss, S., Schalock, R. L., Snell, M. E.,Stark,

J. A. (1992). Mental retardation: Definition,

classification, and systems of supports (9th ed.).

Washington, DC: American Association on

Mental Retardation.

Maulik, P. K., Mascarenhas, M. N., Mathers, C. D.,

Dua, T., & Saxena, S. (2011). Prevalence of

intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of

population-based studies. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 419436.

McCarver, R. B., & Campbell, V. A. (1987). Future

developments in the concept and application

of adaptive behavior. Journal of Special Education, 21, 197207.

Papazoglou, A., Jacobson, L., & Zabel, T. A.

(2013a). More than intelligence: Distinct

cognitive/behavioral clusters linked to adaptive

dysfunction in children. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19, 189197.

Papazoglou, A., Jacobson, L. A., & Zabel, T. A.

(2013b). Sensitivity of the BASC-2 Adaptive

Skills Composite in detecting adaptive impairment in a clinically referred sample of children

and adolescents. The Clinical Neuropsychologist,

27, 386395.

Schalock, R. L., Borthwick-Duffy, S. A., Bradley,

V. J., Buntix, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig,

E. M.,Yeager, M. H. (2010). Intellectual

disability: Definition, classification, and systems

of supports (11th ed.).Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Shelton, T. L., Barkley, R. A., Crosswait, C.,

Moorehouse, M., Fletcher, K., Barrett, S., &

Metevia, L. (1998). Psychiatric and psychological morbidity as a function of adaptive

disability in preschool children with aggressive

and hyperactive-impulsive inattentive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26,

475494.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A.

(2005). Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd

ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance

Service, Inc.

Thompson, J. R., McGrew, K. S., & Bruininks,

R. H. (1999). Adaptive and maladaptive behavior: Functional and structural characteristics.

In R.L. Schalock (Ed.), Adaptive behavior and its

173

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

2014, Vol. 52, No. 3, 165174

measurement: Implications for the field of mental

retardation (pp. 1542). Washington, DC:

American Association on Mental Retardation.

U.S. Department of Education. (2007). 29th annual

report to Congress on the implementation of the

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2007

(Vol. 1). Washington, DC: Author.

Wechsler, D. (2003). WISC-IV technical and

interpretive manual. San Antonio, TX: The

Psychological Association.

Wei, Y., Oakland, T., & Algina, J. (2008).

Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis for

the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-II

Parent Form, Ages 521. American Journal of

Mental Retardation, 113, 178186.

174

AAIDD

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.3.165

Received 7/6/2013, accepted 10/2/2013.

Authors:

Aimilia Papazoglou, Childrens Healthcare of

Atlanta; Lisa A. Jacobson, Kennedy Krieger

Institute; Marie McCabe, Saratoga Springs, NY;

Walter Kaufmann, Boston Childrens Hospital;

T. Andrew Zabel, Kennedy Krieger Institute.

Correspondence concerning this article should be

addressed to Aimilia Papazoglou, Childrens Healthcare of Atlanta, Neuropsychology, Suite 180, 5455

Meridian Mark Road, Atlanta, GA 30342 (e-mail:

emily.papazoglou@choa.org).

Intellectual Disability and DSM-5

Você também pode gostar

- New Terminology For Mental Retardation in DSM-5 and ICD-11: EditorialDocumento3 páginasNew Terminology For Mental Retardation in DSM-5 and ICD-11: EditorialLupita LeyvaAinda não há avaliações

- Development and Standardization of The Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale: Application of Item Response Theory To The Assessment of Adaptive BehaviorDocumento16 páginasDevelopment and Standardization of The Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale: Application of Item Response Theory To The Assessment of Adaptive BehaviorCarolina MoraesAinda não há avaliações

- The Relation Between Intellectual Functioning and Adaptive Behavior in The Diagnosis of Intellectual DisabilityDocumento10 páginasThe Relation Between Intellectual Functioning and Adaptive Behavior in The Diagnosis of Intellectual DisabilityCristinaAinda não há avaliações

- Practical - 1: Changes Made in The Classificafatory System From DSM - Iv To DSM - VDocumento5 páginasPractical - 1: Changes Made in The Classificafatory System From DSM - Iv To DSM - VRakesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- APA - DSM 5 Intellectual Disability PDFDocumento2 páginasAPA - DSM 5 Intellectual Disability PDFEmil Mari FollosoAinda não há avaliações

- TEXTO INGLES 2021pdfDocumento10 páginasTEXTO INGLES 2021pdfLaura RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Borderline Intellectual Functioning: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocumento28 páginasBorderline Intellectual Functioning: A Systematic Literature ReviewlbburgessAinda não há avaliações

- DSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetDocumento2 páginasDSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact Sheetapi-242024640Ainda não há avaliações

- DSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetDocumento2 páginasDSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetMelissa Ortega MaguiñaAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual Disability Fact Sheet PDFDocumento2 páginasIntellectual Disability Fact Sheet PDFAle M. Martinez100% (2)

- Leichsenring 2019Documento14 páginasLeichsenring 2019Ekatterina DavilaAinda não há avaliações

- Oltmanns & Widiger in Press PiCDDocumento54 páginasOltmanns & Widiger in Press PiCDDaniel KoffmanAinda não há avaliações

- Mental RetarditionDocumento14 páginasMental RetarditionDenvergerard Tamondong100% (1)

- Adaptive Behavior Assessment - Tasse (2009)Documento10 páginasAdaptive Behavior Assessment - Tasse (2009)Karen Steele50% (2)

- Personality Disorder Intro SampleDocumento17 páginasPersonality Disorder Intro SampleCess NardoAinda não há avaliações

- Personality Inventory For DSM-5 (PID-5) in Clinical Versus Nonclinical Individuals: Generalizability of Psychometric FeaturesDocumento12 páginasPersonality Inventory For DSM-5 (PID-5) in Clinical Versus Nonclinical Individuals: Generalizability of Psychometric FeaturesJasmine BurgosAinda não há avaliações

- Critically Evaluate The Difference Between DSM 4 and DSM 5EVFDocumento3 páginasCritically Evaluate The Difference Between DSM 4 and DSM 5EVFNaganajita ChongthamAinda não há avaliações

- DSM 5 - DSM 5Documento7 páginasDSM 5 - DSM 5Roxana ClsAinda não há avaliações

- PSY403 - Ivon Sagita - 1Documento8 páginasPSY403 - Ivon Sagita - 1Muhammad Isnaeni Rizqi WijayaAinda não há avaliações

- DSM5-Reflexion in AutismDocumento7 páginasDSM5-Reflexion in AutismBianca NuberAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Characteristics of Intellectual Disabilities - Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children - NCBI BookshelfDocumento6 páginasClinical Characteristics of Intellectual Disabilities - Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children - NCBI BookshelfArhatya MarsasinaAinda não há avaliações

- CAARS ReviewDocumento7 páginasCAARS ReviewRAMSES REZA RENDONAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Cognitive Characteristics of Autism Spectrum DisorderDocumento14 páginasReview of Cognitive Characteristics of Autism Spectrum DisorderKarel GuevaraAinda não há avaliações

- Le FaivreDocumento7 páginasLe FaivreOtra PersonaAinda não há avaliações

- Beda DSM IV Vs DSM 5Documento19 páginasBeda DSM IV Vs DSM 5strioagung06Ainda não há avaliações

- Opinions of People Who Self-Identify With Autism and Asperger's On DSM-5 CriteriaDocumento11 páginasOpinions of People Who Self-Identify With Autism and Asperger's On DSM-5 CriteriaAndrés SánchezAinda não há avaliações

- A Study of Co-Morbidity in Mental RetardationDocumento9 páginasA Study of Co-Morbidity in Mental RetardationijhrmimsAinda não há avaliações

- Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual 2nd Edition PDDocumento3 páginasPsychodynamic Diagnostic Manual 2nd Edition PDgustiAinda não há avaliações

- Psychometric Properties of The Personality Inventory For Dsm-5 in A Romanian Community SampleDocumento18 páginasPsychometric Properties of The Personality Inventory For Dsm-5 in A Romanian Community SampleDianaStanciuAinda não há avaliações

- WAISIV LDSQ AuthorDocumento19 páginasWAISIV LDSQ AuthorSudarshana DasguptaAinda não há avaliações

- Cicero,+0210 1696 2021 0052 0003 0029 0036Documento8 páginasCicero,+0210 1696 2021 0052 0003 0029 0036Alba subiñas poloAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual DevelopmentalDocumento29 páginasIntellectual DevelopmentalAnne de AndradeAinda não há avaliações

- Pauta Discapacidad N&ADocumento29 páginasPauta Discapacidad N&APedro Y. LuyoAinda não há avaliações

- Berghuis Et Al., GAPD CP&P 2012Documento14 páginasBerghuis Et Al., GAPD CP&P 2012Feras ZidiAinda não há avaliações

- ABAS Manual Chapter 1 PDFDocumento14 páginasABAS Manual Chapter 1 PDFTeodora Rusu100% (2)

- Intelligence Measures As Diagnostic Tools For Children With SpecificDocumento6 páginasIntelligence Measures As Diagnostic Tools For Children With Specificjulicosita19Ainda não há avaliações

- For Immediate Release Commentary Takes Issue With Criticism of New Autism DefinitionDocumento2 páginasFor Immediate Release Commentary Takes Issue With Criticism of New Autism DefinitionElyssa DurantAinda não há avaliações

- A Five-Factor Measure of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Traits PDFDocumento38 páginasA Five-Factor Measure of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Traits PDFRANJINI.C 20PSY042Ainda não há avaliações

- Personality DisordersDocumento5 páginasPersonality DisordersFabianAinda não há avaliações

- Schema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD-11 and DSM-5Documento13 páginasSchema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD-11 and DSM-5benoitmonchotteAinda não há avaliações

- 10.1.1.627.9556 Millon PDFDocumento12 páginas10.1.1.627.9556 Millon PDFGERMAN ANDRES BARON BONILLA100% (1)

- Foley-Nicpon 2017Documento13 páginasFoley-Nicpon 2017Jennifer TanAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders: An IntroductionNo EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders: An IntroductionAinda não há avaliações

- The Five-Factor Personality Inventory For ICD-11 - A Facet-Level Assessment of The ICD-11 Trait ModelDocumento38 páginasThe Five-Factor Personality Inventory For ICD-11 - A Facet-Level Assessment of The ICD-11 Trait Modeld55v9x8846Ainda não há avaliações

- An Overview of The DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality DisordersDocumento7 páginasAn Overview of The DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality DisordersJosé Ignacio SáezAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual Development DisordersDocumento9 páginasIntellectual Development DisordersCindy Van WykAinda não há avaliações

- Dale Et Al (2021) WISC-V and AutismDocumento17 páginasDale Et Al (2021) WISC-V and Autismliliana temudo romãoAinda não há avaliações

- A Comparison of WISC-IV and WISC-V VerbalDocumento12 páginasA Comparison of WISC-IV and WISC-V VerbalKarel GuevaraAinda não há avaliações

- Beyond The DSM-IV Assumptions, Alternatives, and Alterations PDFDocumento10 páginasBeyond The DSM-IV Assumptions, Alternatives, and Alterations PDFMira BurovaAinda não há avaliações

- The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Version 2 (PDM-2) : Assessing Patients For Improved Clinical Practice and ResearchDocumento25 páginasThe Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Version 2 (PDM-2) : Assessing Patients For Improved Clinical Practice and ResearchSilvia R. AcostaAinda não há avaliações

- Skodol Et Al 2011 Part IIDocumento18 páginasSkodol Et Al 2011 Part IIssanagavAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Response Bias On The Personality Inventory For DSMDocumento5 páginasThe Effect of Response Bias On The Personality Inventory For DSMОксана ГриневичAinda não há avaliações

- Adhd MakaleDocumento11 páginasAdhd MakaleNESLİHAN ORALAinda não há avaliações

- CHP 3A10.1007 2F978 1 4419 0234 4 - 8Documento17 páginasCHP 3A10.1007 2F978 1 4419 0234 4 - 8astrimentariAinda não há avaliações

- NIH Public AccessDocumento20 páginasNIH Public AccessMyriam PaquetteAinda não há avaliações

- Subtypes of Psychopathology in Children Referred For Neuropsychological AssessmentDocumento15 páginasSubtypes of Psychopathology in Children Referred For Neuropsychological Assessmentdrake2932Ainda não há avaliações

- Dsm-5 and Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : An Opportunity For Identifying Asd SubtypesDocumento6 páginasDsm-5 and Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : An Opportunity For Identifying Asd SubtypesLuis SeixasAinda não há avaliações

- Research Final Paper-Brenna SchulteDocumento15 páginasResearch Final Paper-Brenna Schulteapi-610116630Ainda não há avaliações

- Neo Ffi DissertationDocumento5 páginasNeo Ffi DissertationWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Chapter 10Documento5 páginasChapter 10Lorie Jane UngabAinda não há avaliações

- D Example-VIT (M, WO)Documento8 páginasD Example-VIT (M, WO)Anonymous q084Nx6FUAinda não há avaliações

- FILE - 20200610 - 183606 - Constructive AlignmentDocumento19 páginasFILE - 20200610 - 183606 - Constructive AlignmentThanh ThanhAinda não há avaliações

- Celie Case StudyDocumento7 páginasCelie Case Studyapi-491868957Ainda não há avaliações

- Problem StatementDocumento2 páginasProblem Statementikx pxndaAinda não há avaliações

- Artigo - Pildes, S. and Moon, K. A. I Didn - T Know You Felt That Way - The Practice of Client-Centered Couple and Family TherapyDocumento10 páginasArtigo - Pildes, S. and Moon, K. A. I Didn - T Know You Felt That Way - The Practice of Client-Centered Couple and Family TherapyGabriel RochaAinda não há avaliações

- 20th Century War PoetryDocumento3 páginas20th Century War Poetryapi-350339852Ainda não há avaliações

- Nielsen, T.Documento10 páginasNielsen, T.Amanda MunizAinda não há avaliações

- MPDF PDFDocumento3 páginasMPDF PDFP'ken ZeeAinda não há avaliações

- Visit ReportDocumento2 páginasVisit ReportGirish Pal100% (3)

- Human Resource ManagementDocumento14 páginasHuman Resource ManagementPuneet BansalAinda não há avaliações

- Creativity FrameworkDocumento18 páginasCreativity FrameworkAshkan AhmadiAinda não há avaliações

- DLL Food-Processing-Sugar-ConcentrationDocumento7 páginasDLL Food-Processing-Sugar-ConcentrationErma Jalem71% (7)

- Types of StressorsDocumento4 páginasTypes of StressorsIceyYamahaAinda não há avaliações

- Competency Based HRM ModuleDocumento4 páginasCompetency Based HRM ModuleErlene LinsanganAinda não há avaliações

- Humss 7 Cur Map Q2Documento7 páginasHumss 7 Cur Map Q2Martie AvancenaAinda não há avaliações

- Rethinking Procrastination: Positive Effects of "Active" Procrastination Behavior On Attitudes and PerformanceDocumento22 páginasRethinking Procrastination: Positive Effects of "Active" Procrastination Behavior On Attitudes and PerformanceJuniii OktavianiAinda não há avaliações

- SAMHSA Psychological Response AidDocumento2 páginasSAMHSA Psychological Response AidAiszellnutAinda não há avaliações

- Maslach Leiter Burnout Stress Concepts Cognition Emotionand BehaviorDocumento5 páginasMaslach Leiter Burnout Stress Concepts Cognition Emotionand BehaviorMOHD SHAHRIZAL CHE JAMEL100% (1)

- Learner Progress Report Card: Name: Tisha Nair Grade: Vii Eins Roll No: 19Documento4 páginasLearner Progress Report Card: Name: Tisha Nair Grade: Vii Eins Roll No: 19Tisha NairAinda não há avaliações

- Mackenzie, G. (2018) - Building Resilience Among Children and Youth With ADHDDocumento18 páginasMackenzie, G. (2018) - Building Resilience Among Children and Youth With ADHDjuanAinda não há avaliações

- Background of The Study FinalDocumento8 páginasBackground of The Study FinalBIEN RUVIC MANEROAinda não há avaliações

- SOSC1960 Discovering Mind and Behavior: Wednesdays & Fridays 1:30 - 2:50 PMDocumento30 páginasSOSC1960 Discovering Mind and Behavior: Wednesdays & Fridays 1:30 - 2:50 PMericlaw02Ainda não há avaliações

- 5043 AssignmentDocumento6 páginas5043 AssignmentFoo Siew YokeAinda não há avaliações

- wk1 Assignment - ch2 Theories of Development Deema Othman 2Documento2 páginaswk1 Assignment - ch2 Theories of Development Deema Othman 2api-385327442Ainda não há avaliações

- Abu Dhabi and Dubai 2020 MFDocumento1 páginaAbu Dhabi and Dubai 2020 MFYaryna Telenko de OvelarAinda não há avaliações

- Summary 2 - PhobiaDocumento2 páginasSummary 2 - PhobiaAmutha Ammu0% (1)

- Soccer Block PlanDocumento2 páginasSoccer Block Planapi-237645751Ainda não há avaliações

- SHS DAILY LESSON LOG (DLL) TEMPLATE (By Ms. Gie Serrano)Documento3 páginasSHS DAILY LESSON LOG (DLL) TEMPLATE (By Ms. Gie Serrano)Irah Rendor SasaAinda não há avaliações

- The 16-Item Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale (MDS-16)Documento3 páginasThe 16-Item Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale (MDS-16)Diogo Desiderati100% (2)