Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Plato PDF

Enviado por

Zakuta123Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Plato PDF

Enviado por

Zakuta123Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Plato's Laches

Author(s): Robert G. Hoerber

Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Apr., 1968), pp. 95-105

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/269126

Accessed: 18-09-2015 19:30 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Classical Philology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CLASSICAL

PHILOLOGY

VOLUME LXIII, NUMBER

April 1968

PLATO'S LACHES

ROBERTG. HOERBER

generally not considered Also the dramatic date of the Laches is

one of Plato's masterpieces, the a question on which general agreement

Laches has been the subject occasion- should not be difficultto attain, even though

ally of specific study during the twentieth a specific year may not be obtainable. The

century.1 Only two scholars, according to dialogue itself furnishes both a terminusa

our findings, have questioned its genuine- quo and a terminusad quem. The references

ness-Ast2 and Madvig;3 other skeptical to the battle at Delium (181B, 188E-189B)4

students of the nineteenth century, such as set the one date at 424 B.C.; the presence of

Schleiermacher, Stallbaum, Socher, Suse- Laches, who fell in battle at Mantinea,5

mihl, and Steinhart, regarded the Laches as limits the other extreme to 418 B.C. To

genuine. Both Ast and Madvig base their narrow the range between these poles is

negative judgment on completely subjec- more a matter of conjecture. Adam Fox

tive standards; the former on the basis of sets the date at 422, but offers no reasons.6

alleged logical and dramatic defects, the Kurt Hildebrandt suggests 421-418, after

latter on the fact that in the Laches (as well the Peace of Nicias, when ". . . Nikias,

as in the Lysis and Charmides) Socrates der Aristokrat, die politische Fiihrung des

treats young and uneducated dialogists in Staates hat.. ."7 Paul Shorey sets the

the same manner in which he handles the scene "about the year 420 during the Pelosophists in the genuine dialogues. Since the ponnesian War"; his notes, however, refer

subjective judgment of Ast and Madvig merely to the two terminimentionedabove.8

apparently has influenced no other Plato- A. E. Taylor prefers 423 B.C.: "The refnists, we may consider the possible spuri- erences to the comparative poverty of

ousness of the Laches a dead issue and Socrates-it is not said to be more than

assume its genuineness.

comparative (186c)-may remind us that

LTHOUGH

NOTES

1. K. Joel, "Zu Platons Laches," Hermes, XLI (1906),

310-18; R. Meister, "Thema und Ergebnis des platonischen

Laches," WS, XLII (1920), 9-23, 103-14; G. Ammendola,

Platone:

II "Lachete"

(Naples,

1928);

W. Steidle,

Plato's Laches," CJ, LVI (1960), 123-32; M. J. O'Brien, "The

Unity of the Laches," YCS, XVIII (1963), 131-47; P. Vicaire,

Platon: Laches et Lysis (Paris, 1963).

2. Leben undSchriften Platons, pp. 451-56, referred to by G.

Grote, Plato and the Other Companions of Socrates (London,

1875), I, 481.

3. Adversaria Critica, I, 402, discussed by H. Raeder,

Platons philosophische Entwicklung (Leipzig, 1905), p. 91.

4. Cf. Symp. 220E-221B; Apol. 28E.

5. Thuc. 5. 74. 3; cf. 5. 61. 1.

6. Plato for Pleasure (London, 1962), p. 168.

7. Platon: Logos und Mythos (Berlin, 1959), p. 76.

"Der

Dialog Laches und Platons Verhdltnis zu Athen in den

Fruihdialogen," Mus. Helv., VII (1950), 129-46; G. Galli,

"Sul Lachete di Platone" (Turin, 1953); H. H. Martens, Die

Einleitung der Dialoge Laches und Protagoras: Untersuchungen

zur Technik des platonischen Dialoges (diss., Keil, 1954); P.

Grenet, "Note sur la structure du Laches," Melanges dephilo-

sophie grecque(Paris, 1956), pp. 121 ff.; G. Galli, Socrate ed

alcuni dialoghi platonici

(Turin,

1958), pp. 153 ff.; E. V.

Kohak, "The Road to Wisdom: Lessons on Education from

8. WhatPlato Said (Chicago, 1957), pp. 106, 484.

95

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96

ROBERT G. HOERBER

Aristophanes and Amipsias both made this

a prominent feature in their burlesques of

him (the Clouds of Aristophanes and the

Connus of Amipsias), produced in 423. It

points to the same general date that the

two old men should be thinking of the

speciality of Stesilaus as the thing most

desirable to be acquired by their sons.

After the peace of Nicias, which was expected to put an end to the struggle between

Athens and the Peloponnesian Confederation, it would not be likely that fathers

anxious to educate their sons well should

think at once of o&rAo/aiaXas the most

promising branch of education."9 Since

the arguments of Hildebrandt and Taylor

are not overwhelming, we probably should

not attempt to dogmatize whether the discourse supposedly occurred preceding or

following the Peace of Nicias. That the

dramatic date is near 421 is about as

specific as we should be, noting further that

both Laches and Nicias, who are the chief

dialogists with Socrates, were instrumental

in negotiating the Peace of Nicias.10

At first glance the referenceto Damon as

still alive may appearto be an anachronism.

Since he was the teacher of Pericles,' 1being

in his prime around 460 and born about

500 B.C., his introduction by Socrates to

Nicias as a teacher of Nicias' son Niceratus

(180C-D) may seem strange for a dramatic

date around 421; for Damon would be

approximately an octogenarian and possibly too old to continue his profession.

Taylor notes, however, that since Laches

has not even met Damon (200B), we may

assume that "Damon is living in retirement

from society generally."12 Other Greeks,

moreover, continued mental activities

either as octogenarians (e.g., Plato) or far

beyond that age (e.g., Isocrates); and

references to Damon as still alive occur

also in the Republic(40GB-C,424C), whose

dramatic date is around 421 B.C.13Socrates

then would be under fifty, and Plato correctly depicts him as relatively youngyounger than Nicias and Laches (181D),

much younger than Lysimachus (180D-E)

and the octogenarian Damon. Of Socrates'

vigor his prowess at Delium, only a few

years previous, is a proof.14 The references

to Damon as still living and to Socrates as

relatively young, therefore, offer no obstacles to a dramatic date of approximately

421.

Concerning the scene of the Laches there

is no decisive evidence. Only one scholar

ventures a guess, supposing the place of

the discussion to be an Athenian palestra.15

His statement may very well be correct,

but it must remain an assumption.

The time of composition is another

question on which there is no conclusive

evidence, although almost all Platonists

prefer an early date. Schleiermacher,Stallbaum, Socher, and Steinhart assign the

Laches to 406-404 B.C., or several years

before Socrates' death.16 Stallbaum and

Socher see in it adolescentiaevestigia, while

Schleiermacherregardsthe Lachespartially

as a defense of Plato, a young man, for

having attacked Lysias and Protagoras,

much older men, in the Phaedrus and

Protagoras respectively. R. S. Bluck,17

G. C. Field,18 R. C. Lodge,19 D. Ross,20

NOTES

9. Plato: The Man and His Work (London, 1949), p. 58.

10. Thuc. 5. 43. 2.

11. Isocr. Antid. 235. For Damon, cf. K. Freeman, Ancilla

to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers (Oxford, 1948), pp. 70-71;

The Pre-Socratic Philosophers (Oxford, 1949), pp. 207-8;

P1. Alc. I. 118C.

12. Op. cit. (n. 9), p. 58, n. 1.

13. Cf. Fox, op. cit. (n. 6), pp. 168-69.

14. Cf. Symp. 221A-B; Apol. 28E. Cf. Prot. (317C, 361E)

for Socrates as "young."

15. Shorey, op. cit. (n. 8), p. 106.

16. Cf. Grote, op. cit. (n. 2), I, 481.

17. Plato's Life and Thought (London, 1949), p. 60.

18. The Philosophy of Plato (Oxford, 1956), p. 209; Plato

and his Contemporaries (London, 1948), p. 105.

19. Plato's Theory of Art (London, 1953), p. 3.

20. Plato's Theory of Ideas (Oxford, 1953), p. 10.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

97

PLATO'S"LACHES"

P. Vicaire,21 E. Dupreel,22 K. Hildebrandt,23 A. Fox,24 H. Raeder,25 and C.

Ritter26 also place the Laches early, but

after the death of Socrates, without

stressing any particular reason. The remarks of Grote,27 Taylor,28 Shorey,29 G.

M. A. Grube,30J. Gould,31and A. Koyre32

imply general agreement with such a date.

In the opinion of R. Robinson the "discussion of What-is-X ?," as found in

the Laches, is characteristic of early dialogues.33 Several scholars, also assuming

a comparatively early date of composition,

attempt to relate the Laches to other dialogues. U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff

would place the Laches before the Lysis,

Charmides, and Euthyphro, but after the

Protagoras, which it attempts to correct.34

Von Arnim35 and Schleiermacher36 also

consider the Laches as an improvement on

the Protagoras. Raeder37 and H. J.

Krimer,38 however, put the Laches before

the Protagoras. According to E. R. Dodds

the Laches preceded the Gorgias, since the

reference to courage at Gorgias 507B presupposes the fuller discussion of the

Laches.39Both Schleiermacherand Raeder

date the Laches before the Mleno,because

in their opinion the Meno solves the problem posed in the Laches and Protagoras.40

Thus there seems to be general agreement,

with or without substantiating evidence,

that the Laches is probably an early dialogue, although its specific relation to

certain other early compositions remains

a moot point.41

In previous studies of particular dialogues we found that Plato apparently employed dramatic techniques as clues to the

philosophic content of the composition.42

In the Laches the dramatic clue which

seems most predominant is the use of

"doublets" or "pairs." The characters, in

the first place, appear in pairs: Lysimachus

and Melesias; their children, Aristeides and

Thucydides; Nicias and Laches. All of

these personae take part in the discourse,

although the children speak only once

(181A) and Melesias utters merely seven

short phrases (184E-185B). Also persons

who are present in name only occur in

pairs: the two famous fathers of Lysimachus and Melesias, also named Aristeides and Thucydides (179A-D); two

musicians, Agathocles and Damon (180D);

two poets, Solon and Homer (188B, 189A,

191A-B, 201B). The plan of pairs appears

to permeate also other characters either

taking part in the discussion or merely

mentioned: Stesilaus, who previously had

NOTES

21.

22.

1922),

23.

24.

25.

26.

Platon: Critique litteraire (Paris, 1960), pp. 8-9.

La Legende socratique et les sources de Platon (Paris,

p. 15.

Op. cit. (n. 7), p. 396.

Op. cit. (n. 6), p. 168.

Op. cit. (n. 3), p. 57.

Platon: Sein Leben, seine Schriften, seine Lehre (Munich,

1910), I, 273.

27. Op. cit. (n. 2), I, 468-81.

28.

29.

30.

31.

p. 57.

Op. cit. (n. 9), pp. 57-64.

Op. cit. (n. 8), pp. 106-12.

Plato's Thought (London, 1935), pp. 216-18.

The Development of Plato's Ethics (Cambridge,

1955),

32. DiscoveringPlato (New York, 1946), pp. 58-60.

33. Plato's Earlier Dialectic (Oxford, 1953), p. 49.

34. Platon: Sein Leben und seine Werke (Berlin,

1959),

pp. 139-40.

35. Platos

"Phaidros"(Leipzig, 1914), p. 27, referred to by Shorey, op.

cit. (n. 8), p. 486.

36. Platons Werke (Berlin, 1804), I, 1, 321 and I, 2, 5,

referred to by Raeder, op. cit. (n. 3), p. 110.

37. Raeder, op. cit. (n. 3), pp. 110-11.

38. Arete bei Platon

und Aristoteles

und

die

Entstehungszeit

des

1959),

the Republic (430C); namely Siebeck, Untersuchungen zur

Philosophie der Griechen (Freiburg, 1888), II, 126, as discussed by Shorey, The Unity of Plato's Thought (Chicago,

1960), p. 78, and by H. Raeder, op. cit, (n. 3), p. 211.

42. "Plato's Euthyphro,"Phron., III (1958), 95-107; "Plato's

Lysis," Phron., IV (1959),

Jugenddialoge

(Heidelberg,

p. 493.

39. Plato: Gorgias (Oxford, 1959), p. 22.

40. Raeder, op. cit. (n. 3), p. 130, who refers to Schleiermacher, op. cit. (n. 36), II, 1, 334.

41. Only one writerventures to place the Laches subsequent

to the Republic,as the fuller discussion of courage promised in

15-28;

"Plato's Meno," ibid., V

(1960), 78-102; "Plato's Lesser Hippias," ibid., VII (1962),

121-31; "Plato's Greater Hippias," ibid., IX (1964), i43-55.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98

ROBERT G. HOERBER

exhibited his prowess in hoplomachia,and

the individual who had recommended this

skill to Lysimachus and Melesias (178A1,

179E1-4, 183C8-184A7); Socrates, who

assumes the leading role particularlyin the

latter part of the treatise, and his father,

Sophroniscus (180D7-181BI).

In addition to the appearance of personae in pairs various doublets dominate

the dialogue. Socrates discourses with two

pairs of dialogists: (1) Lysimachus and

Melesias; (2) Nicias and Laches.43Lysimachus compares two types of training:

(1) that given him and Melesias by their

fathers; (2) that which they hope to supply

for their children (179A-180A). Two professions are represented: (1) statesmen, by

Aristeides and Thucydides, the fathers of

Lysimachus and Melesias; (2) generals, by

Nicias and Laches.44 Plato links Damon

with two individuals, Agathocles and

Prodicus, associating him with two areas

of knowledge, music and discrimination of

synonyms (180D, 197D). In music Plato

mentions Damon in two capacities: (1) a

pupil of Agathocles; (2) a teacher of Nicias'

son (180C-D). Plato refers to Nicias' son,

Niceratus, twice (180C-D, 200D). On two

occasions Laches cites the bravery of

Socrates at Delium (181B, 188E-189B).45

To convince Nicias that the discussion

should concern the soul rather than hoplomachia, Socrates gives two examples: (1)

medication for the eyes; (2) bridle for a

horse (185C-D). In stressing the need for

definition Socrates offers two comparisons:

(1) sight; (2) hearing (190A). In attacking

Nicias' definition of courage Laches pre-

sents challenges in two areas: (1) medicine;

(2) farming (195B). Laches then suggests

two other possibilities to which Nicias'

definition might refer: (1) a seer; (2) a god

(195E-196A). Parallelism with the musical

modes occurs twice (188D, 193D-E).

There are two references to Solon (188B,

189A). On two occasions Socrates quotes

Homer, citing both of his poems, and selecting two lines from the Iliad (191A-B,

201B).46 Two participants attempt to

define courage: (1) Laches; (2) Nicias

(190E-199E). Laches ventures two definitions: (1) "remaining in ranks" (19GE);

(2) "wise steadfastness" (192B-D).

Besides the pairs of personae and the

numerous doublets permeating the composition, duality is also the key in the

framework of the treatise as a whole. The

dialogue consists of two main sections:

the first comprises a general discussion on

the education of the youth; the second attempts more specifically the definition of

courage. The dramatic clue to this duality

is the presence and participation of

Lysimachus in the first section, while he

excuses himself from further discourse

approximately in the middle of the dialogue (189C-D). The first section also falls

into two divisions: in the first the subject

centers on hoplomachia;in the second the

topic concerns the education of the soul.

The dramaticclue to this duality is the brief

oral participation of Melesias, whose seven

very short sentences serve the primary

purpose of separatingthe first section of the

discourse into two divisions (184E-185A).

The second section likewise is composed of

NOTES

43. The sole sentence by the children is a reply to a query of

Lysimachus (181A). According to the Theaet. (105E-151A)

Aristeides' failure to benefit from associating with Socrates

was entirely his own fault.

44. There may seem to be some overlapping, since Aristeides

and Thucydides took part also in military campaigns and both

Nicias and Laches negotiated the Peace of 431 B.C. (Thuc.

5. 43. 2); but the predominant profession of Nicias and

Laches remained military, while that of Aristeides, primarily

a rival statesman to Themistocles and the leader in establishing the Delian Confederacy, and of Thucydides, the head of

the aristocratic party in opposition to Pericles, was statesmanship.

45. Symp. 221A-B; Apol. 28E.

46. The first quotation at 191A-B occurs both at II. 5. 223

and 8. 107, while the second phrase is from II. 8. 108; the

reference at 201B is based on Od. 17. 347.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PLATO'S"LACHES"

two parts: in the first, Socrates queries

only Laches; in the second, Socrates and

Laches examine Nicias. Laches' desire to

be relieved from the challenge of defining

courage is the dramatic clue to the duality

of the second section (194B-C); although

Laches continues in the discussion, his

99

position in the second part (of the second

section) shifts from one who answers

Socrates to one who questions Nicias.

On the basis of the pairs, doublets,

and duality in the dialogue, an outline

of the Laches could be constructed as

follows:

I. Problemof education(178A-189C)

A. Value of hoplomachiain education(178A-184D)

1. Plea for advice on hoplomachia(178A-181D)

2. Conflictingadvice on hoplomachia(181E-184D)

B. Educationconcernsthe soul (184E-189C)

1. Advice should come from one with knowledgeand experiencein the care of souls

(184E-187B)

2. Socrates'custom of examiningsouls (187C-189C)

II. Need for definition(189D-201C)

A. SocratesexaminesLaches(189D-194B)

1. Courageis "remainingin ranks"(189D-192A)

2. Courageis "wise steadfastness"(192B-194B)

B. Socratesand LachesexamineNicias (194C-201C)

1. Courageis "knowledgeof whatshouldbe fearedand whatshouldnot" (194C-197D)

2. Socratestests Nicias' definition(197E-201C)

Another clue in the Laches may be deeds substantiate their words and those

characterized as "contrast." Plato con- whose actions do not harmonize with their

trasts the positive advice of Nicias on smooth talk (188C-189B). The courage of

hoplomachia (181E-182D) with the nega- Socrates at Delium (181B, 188E-189B)

tive remarks of Laches (182D-184C). and the failure of Stesilaus in combat

Contrast is evident also in two pairs of (183C-184A) form another marked condialogists who discourse with Socrates, trast, too manifest to be overlooked.

Lysimachus being decidedly more ag- Furthermore, the words and deeds of

gressive and talkative than Melesias, and Socrates agree, those of Stesilaus do not.

Nicias more progressive than Laches.

In fact the contrast between word and

Readers of the Laches, both ancient and deed, logos and ergon, permeates the

current, cannot fail to notice the contrast discussion, setting the stage for the delineabetween Nicias' verbal admission that a tion of several characters. Laches emseer should not control a general (199A) phasizes throughout his comments, deeds,

and Nicias' actual acceptance of the fatal actions, or erga. He is the first to use the

advice of a seer "to remain thrice nine term: en autJi toi ergoi (183C2); he then

days" during the Sicilian Expedition of compares the display by Stesilaus with his

413 B.C.47 In two speeches Laches employs

claims (epideiknymenonvs. legonta, 183D1contrast-between the claims of professed 2; i.e., ergon vs. logos; also the two senses

instructors in hoplomachiaand their failure of epideiknymenon, 183D1 and 183D3,

to perform in practical circumstances present the contrast between action and

(182D-184C), and between those whose theory); finally he finds Stesilaus' erga

NOTE

47. Cf. Thuc. 7. 50. 4.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100

ROBERT G. HOERBER

ridiculous (183C-184A). Again, implying

that some people have become more skilful

without teachers (185E), Laches manifests

a preference for deeds (erga) to theories

(logoi). In describing his twofold reaction

to speeches his stress is on erga, which

either substantiate or refute logoi (188C189B). Laches bases his favorable opinion

of Socrates on Socrates' erga at Delium

(181B, 188E-189B). Each of Laches'

attempts to define courage stresses erga:

(1) courage defined as "remainingin ranks"

(190E) emphasizes action to the exclusion

of possible strategy (logos); (2) courage as

"steadfastness" (192B) also stresses action,

and the addition of the adjective "wise"

(192D), which Socrates construes as technical skill, leads to the complete confusion

of Laches (192E-194B). Plato underlines

Laches' preference for erga by Socrates'

appeal to Laches to "remain" and "be

steadfast" in the search for a definition;

otherwise Laches' action (erga) will not

agree with his definitions (logoi). In spite

of Socrates' plea, based on Laches' own

terms, Laches, the man of erga, cannot

continue the discussion because such logoi

prove to be beyond his ken (194A-B).

Thus Laches lacks the same harmony

which he found wanting in Stesilaus, whom

he severely criticized.

Nicias by contrast represents theory,

discussion, knowledge, or logos. He is

acquainted with Socrates through discourse

(187E-188B), not in battle at Delium. He

has accepted Socrates' advice (logos)

concerning a teacher for his son (180C-D)

although he would prefer Socrates himself

as a tutor for Niceratus (200D). Nicias

bases his favorable reaction to Stesilaus'

display of hoplomachiaon the premise that

as a knowledge or science (mathema,

episteme) it must be beneficial (181E182D); in theory hoplomachialooks promising to him, but he indicates no desire to

test the theory in practice. Also Nicias'

attempted definition of courage ("knowledge of what should be feared and what

should not") emphasizes theory or logos

(194E-195A). In defending his definition

Nicias makes a much better showing

than Laches, distinguishing both between

knowledge and technical skill (195B-196B)

and between true courage and the fearlessness of animals or children (196E-197B).

Nicias' remarks show the result of his

contact with theorists as Damon and

Prodicus (197D, 200A). His distinction

between rash daring and genuine courage,

as well as his differentiation between professional skill and a higher wisdom, underline his preference for logos substantiating

ergon and the inferiority of ergon without

logos. His eagerness for future consultation with Damon and others (200B),

furthermore, reveals his desire for logos.

While Nicias indicates a proficiency in

logos, the readers of the Laches will recall

his deficiency in ergon, when the "chips

were down" at Syracuse in 413 B.C. Also

Nicias, therefore, fails to harmonize logos

with ergon, proving himself in this respect

parallel to Stesilaus and similar to Laches.

Socrates proves to be the hero of the

dialogue. He manifested his prowess in

ergon at Delium; he portrays his wisdom

in logos by examining the attempted

definitions of courage in the dialogue.

Plato depicts Socrates' superiority to each

contestant in his respective area of speciality, surpassing Laches in ergon and

transcending Nicias in logos. Socrates

alone, furthermore, possesses the true

harmony between logos and ergon.

The dramatic technique of contrast,

particularly the contrast between logos

and ergon, as we have observed, serves a

purpose of portraying the participants of

the treatise. But does the technique of contrast, as well as the other dramatic devices

as pairs of personae, various doublets,

and duality of construction, perform any

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

101

PLATO'S"LACHES"

other function in the Laches? In previous

dialogues that we studied, as noted above,48

Plato intertwined dramatic techniques

with the philosophic content of the composition. In the Laches, it appears, the

same may be true; Plato's erga of dramatic

devices should harmonize with his logoi

of philosophic content. A glance at the

philosophic content of the Laches as

observed by several students of Plato may

be revealing.

Professor Shorey states: "In the Laches,

Laches insists exclusively on the temperamental aspect of bravery which opposes it

to other virtues, Nicias on the cognitive

element which identifies it with them."49

Shorey has discerned that according to

Plato two aspects of the soul are involved

in courage: (1) the cognitive or rational;

(2) the temperamental or volitional-or in

the terms of the Republic (435-442): (1)

to logistikon and (2) to thymoeides. The

two elements of the soul must act in unison

to produce true courage. In the words of

the Republic (442 B-C):

KaF

TOVTcp Tcp /LEpEt KaAOV/LEV Eva

ZVapECov 8 7, ot/Lat,

aa

TE

EKaaTOv, oTZav aVToV TO

-roVLOELa, esaaCf

aELVOV

Av7rTjvKat 'Sovc6ivro v7T0-roo Aoyov 7rapayyEAOEv

TE KaL [Lv4

[Text of J. Adam].

The pairs, doublets, and duality in the

Laches certainly seem to point to such a

philosophic tenet.

Commenting on the double application

of the term courage in the Laches (19IDE), Professor Taylor remarks: "A man

may show himself a brave man or a

coward by the way he faces danger at sea,

poverty, disease, the risks of political life;

again, bravery and cowardice may be

shown as much in resistance to the seductions of pleasure and the importunities of

desire as in facing or shirking pain or

According to Taylor this

danger..."50

passage of the Laches (19ID-E) Aristotle

had in mind when he distinguished two

uses of the word "courage" in the Nicomachean Ethics (1115A6-16):

KacL

OPOVls

Se

S7Aov

Oappl7,

M7g7

/1Ev

oVv

EaOT

[zEa0'-r1S

yEyEv77Tac

caVEppoV

O'EaTtv

raiTa

OTl Ta

roflEpa',

Kat

rovyo

7TEpL

9ofolvEOa

WS aS7TAS

ov 6opL'ovTat 7Tpoao0K`aV

aCO

KaKa-

O'Tl

avapEtcaS.

7TEp'

TpLtrov

Kac

E17TEv

KaKOV.

Xa8o0aV 7TrEV`aV

iyEv ov'V 7Tav-rav Ta KaKa', otov

0ofloV'/1Ea

&A' ov 7TEp' 7Travra aOKEL o

Oa'varov,

cMAcav

voaov

aVapELos0

EtVacL

EVLVa

To

oe t71

0c)pV

-r0E

/17 alaXpov,

ernEtK?7Sg

AE'yeTra

yap

TL

yap

otov

ato

o

KacL aL&7/1LWV,

'

KacZ aEL qoflEacOat KacZ KaAov,

'Soot'vEV yap

Lao~x 0o tzev

9%lV/1EVOSX.

yap OogoVZv

SE

/1o

o/1oLOV

Ty

aVaLaXVvToS.

7 09oV/I1EVos9

aVSpELoS9 KarTa

aqos

avapEcc

V7TO TLvWv

/ETa0opav-

yap

TLS

eXEL

KaL 0

Aristotle, in the opinion of other Platonists,

had in mind the passage from the Lawscited

below rather than the Laches; but be that

as it may, again the literary devices of the

Lachescoincidewith its philosophiccontent.

Genuine courage must not be confused

with a lack of fear based on some technical

knowledge, as Socrates warns Laches in

discussing the definition of courage as

"wise steadfastness" (192D-193D). Taylor

comments: "We must not miss the point

of this difficulty. Socrates does not

seriously mean to suggest that 'unwise'

resolution or persistence is courage. His

real object is to distinguish the 'wisdom'

meant by the true statement that courage

is 'wise resolution' from specialist knowledge which makes the taking of a risk less

hazardous. The effect of specialist knowledge of this kind is, in fact, to make the

supposed risk unreal."'51In the Protagoras

(350A) Plato makes the same point on

technical knowledge, as does Aristotle in

the Nicomachean Ethics (1116B3-5):

aOKEL

SE

KacL 27 e/L7eLpLc`a

KaL 0 ?2WKpaT27S

7 7TEpL EKaarTa av&pEL'

27627A ErnaT

'I127v

ElvaL Tr7V

ElvaL- oOSEv

cvopELcav.

Once more the literary techniques of the

Laches harmonize with the philosophic

tenets.

NOTES

48. Cf. n. 42.

50. Op. cit. (n. 9), pp. 60-61.

49. Op. cit. (n. 41), p. 15.

51. Ibid., p. 62.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102

ROBERT G. HOERBER

Another distinction taught in the Laches

is that between true courage and rash

action, between genuine bravery based on

knowledge and merely emotional fearlessness of beasts and infants (196E-197E).

Taylor notes that we must "distinguish

between natural high temper and fearlessness (-ro' 4colov) and genuine courage

(rO &v3pEZov) . .. Native fearlessness is a

valuable endowment, but it is only in a

human being that it can serve as a basis for

the development of the loyalty to principle

we call courage, and it is only in 'philosophers' that this transformation of mere

'pluck' into true valiancy is complete."52

Plato maintains a similar distinction in the

Protagoras (350B-351B, 360A-E); in the

Laws the distinction remains although

the nomenclature varies (963E):

A(S.

'Epd-riao'v

/E

TL

rOTe

eV

7rpOaayOpEVOVTESr

Svo Wa'AtvavTa 7rpTpoaCf7o/Ev, To tkeV

aLTLav, OTL

Opov77aLv. fpa- yap aot 7%7v

To /1EV EaTLV7TEpLOo'fOV, OV KaL Ta 07pUXa

IIETEXEL,i7S

TWV 7FCtSwv 7071 TZv 7raTvv VEWV'

KaC TO

aVSpELfaS9,

rY

aVspfEa

aveU yap Ao'yov Kat oVaaT ytyVerat

OVX7 acvv

apeT77V

allpoTEpa,

&VSpELaV, TO SC

SC

pOvtpO6 g TE

Ovy)

7w7TOTe OVT EaTv

OVs

a V AO'yov

cyEVETO

COVTOSg

KaL

VOVV

fxovaa

avOts7OTE

oVT'

yEVafTaL,

fTepOv.

The various doublets and the dual construction of the Laches again are in agreement with the teaching of the treatise.

Taking a clue from the literary devices of

the Laches and its delineation of character,

we may venture a further step in the philosophic content of the composition. Not only

are two aspects of the soul involved in

genuine courage, but also true bravery

implies both knowledge (as presented by

Nicias) and action (as emphasized by

Laches). The two aspects of the soul

(rational and volitional) and its two functions of knowledge and action present

themselves in Laches' second attempt in

defining courage and in Nicias' sole definition. "Wise steadfastness" implies both

pairs (rational and volitional; knowledge

and action); but Laches emphasizes action

or volition ("steadfastness"), and fails

to defend the definition because he does

not comprehend the proper connotation

of "wise." Nicias, on the contrary, stresses

in his definition the element of reason and

knowledge; his defense fails because he

cannot explain the object of the knowledge

which would distinguish courage from

virtue. Viewing these two definitions as

pairs which Plato is contrasting one with

the other, or as doublets which infer dual

aspects of one concept, we might notice that

each supplies the lack of the other. Laches,

in defining courage as "wise steadfastness,"

should have explained "wise" as knowledge concerning "what should be feared

and what should not." Nicias' definition,

which is accepted in other compositions of

Plato (Rep. 429B-C, 442C; Prot. 360D),

could be interpreted as a knowledge

coupled with steadfastness. M. J. O'Brien

recently has observed: "The definitions of

Laches and Nicias complement each other

too well not to suggest conscious contrivance. The dialogue, when it is interrupted,

is moving towards a conception of courage

which will join knowledge of good and evil

with a steadfast quality of soul."'53 We

wish to add that such a conceptual attainment in the Laches harmonizes with its

literary clues.

While the conceptual attainment concerning the concept of courage is one accomplishment of the Laches, another

dramatic device involving the schema of

the treatise suggests a further purpose and

deeper achievement. We refer to the fact

that four speakers carry on practically all

the discourse: Lysimachus, Laches, Nicias,

and Socrates. As noted above, the participation of several dialogists divides the

NOTES

52. Ibid., p. 63.

53. Op. cit. (n. 1), p. 140.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PLATO'S"LAcHEs"

Laches into four principal divisions.54

The discussion, furthermore, begins by discussing the education of the sons of Lysimachus and Melesias and ends with the

dialogists planning additional education for

themselves, with the concept of courage

occupying approximately only ten of the

twenty-four Stephanus pages. The employment of the four principal speakers,

the division into four main sections, and

the prominence given to education could

suggest that the theme of the treatise is

education discussed on four distinct levels.

The suggestion seems worthy of investigation.

The mention of education on four distinct levels brings to mind Plato's figure of

the Divided Line in the Republic (506B51 IE, 533C-534A), with its division into:

(1) eikasia, (2) pistis, (3) dianoia, (4) noesis.

The parallel between the Divided Line and

the movement of the Laches is surprisingly

similar. Lysimachus in broaching the

problem of education reveals that he is

living in a world of eikasia or shadows,

images, and reflections concerning the

education of the young. The realm of

experience is one step beyond him. Although from the same deme as Socrates,

he had not made his acquaintance, but

merely had heard the children speak of

someone by that name (180C-E). In

searching for a teacher for his offspring,

likewise, he had received a recommendation concerning the value of hoplomachia,

and entertains the notion that such

"shadowboxing" may be instrumental in

the future success of his son (179E). Lysimachus is groping for something more

steady than his world of shadows; he has

103

decided to consult men who have attained

some experience. Lysimachus represents

the lowest section of the Divided Line,

the area of eikasia.

Laches is a man of experience, living on

the level of pistis. He has had experience in

actual battle, and he will die on the battle

field.55He judges Socrates on the basis of

their mutual experience at Delium (181B,

188E-189B). Laches' first attempted definition of courage ("remaining in ranks") is

limited to his very narrow military experience. Even his second attempted definition ("wise steadfastness") he cannot

defend when Socrates interprets "wise" as

technical wisdom based on the area of

experience (192E-193D). Laches is a man

of action, not of theory; his world consists

of erga, not logoi.56 Althoughsuperiorto

Lysimachus in discourse, the queries of

Socrates and the suggestions of Nicias

confuse him. Laches' level is clearly

limited to pistis, one step above that of

Lysimachus.

Nicias, according to Plato's portrayal,

is reaching toward the level of dianoia, the

area of mental concepts. Although Nicias

took a conservative stand concerning the

Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition,57 Plato depicts him in the Laches as

rather progressive. He is willing to give an

opportunity to hoplomachia in education

(181E-182D). Nicias seems to appreciate

the challenge of Socrates' elenchus (187E188C); he would welcome Socrates as a

tutor for his son (200D); currently he is

content with following Socrates' suggestion

of Damon as a teacher of Niceratus (180CD); apparentlyhe has learned from Damon

to discriminatebetween apparentsynonyms

NOTES

54. Other minor "foursomes" in the Laches are the four

references to Damon (180D, 197D, 200A?200B) and Socrates'

emphasis in the middle of the discussion that courage involves

four areas: pleasure, pain, desire, fear (19lD6-E7).

55. Cf. n. 5.

56. Laches has never seen the theorist Damon (200B).

57. Cf. Thuc. 4-7 passim, esp. 5. 16. 1, 7. 42-43, 7. 48-50;

Plut. Vitae(Nicias); Aristoph. Av. 640 and Eq. 358.

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104

ROBERT G. HOERBER

(197D). His definition of courage ("knowledge of what should be feared and what

should not") and his subsequent defense of

it betray a fairly advanced stage of mental

concepts. Not only is his definition of

courage acceptable in the Republic(429B-C

442C) and Protagoras (360D), but also his

defense of it points to some supremescience

of teleology (195B-196A). Nicias is a man

of logoi, indicating ability to follow

Socrates' questioning, and showing the

results of association with other theorists

such as Damon. His theories, hypotheses,

and mental concepts place him above the

pistis of Laches, and closer to the level of

dianoia.

Socrates, of course, would represent the

highest stage, the area of noesis. He is

reaching toward an arche or first principle

by testing the various theories or hypotheses through dialectic elenchus. Socrates

refrains from any clearly cut conclusions;

his purpose rather is to lead the dialogists

and the reader to personal reflection. He

refusesthe use of any narrativein the type of

a lecture; his method is dialectic. The opening query concerning education of the

youth Plato leads through the four stages

of the Divided Line, also giving sufficient

dramatic clues concerning the concept of

courage. The dialogue itself is Plato's

answer to the opening query: Socratic

elenchus is the key to education. Plato

no doubt named the treatise after Laches

because Laches represents the level of the

masses in need of education, and does

make a better showing than Nicias at the

conclusion of the composition by attacking

Nicias with some success. Laches portrays

the doxa of the lower half of the Divided

Line; true education consists in elevating

doxa to the level of episteme.

At the conclusion of the treatise Plato

presents another literary hint. Socrates'

suggestion for further study (201A-C)

should be a clue to the reader that the

Laches deserves several re-examinations,

if it is to serve as a tool in the mental obstetrics for which Plato intended his

dialogues. Upon re-examination, for instance, the reader, recalling the reference

to Prodicus (197D), should note that to

rise above the levels of Lysimachus, of

Laches, and of Nicias distinction must be

made between such terms as mathema

and epitedeuma,as well as between tharsos

and andreia. Lysimachus and Nicias reveal

complete lack of discrimination between

mathema and epitedeuma, consistently

regarding hoplomachia as a mathema

(179D-182C); Nicias even refers to it as

episteme (182C7). Laches proposes that

hoplomachia may not be a mathema

(182D-184C), yet he also refers to it as

episteme (184C1-4), which may reflect

irony. The final appearance of these two

terms occurs in a remark of Socrates

(190E), whose phraseology (ex epitedeumaton te kai mathematon)seems to suggest

to the reader that a differentiation between

these two nouns is in order. While both

Nicias and Laches employ cognates of

tharsos and andreia indiscriminately in

the early part of the composition (182C,

184B), the subsequent remarks of Nicias

(196E-197D) make it sufficiently clear

to the reader that a discrimination

between these apparent synonyms is

necessary.

Plato's Socratic dialogues are unique

both in the field of philosophy and in the

area of literature. His dialectic treatises,

frequently without concise conclusions as

found in prose narrative, have presented

problems to the interpreter. Some regard

these compositions primarily as literary

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PLATO'S "LACHES"

endeavors to portray the character and

method of Socrates.58 Other students,

searching for philosophic content, differ

widely, for example, in their interpretation of the Laches-either as an attack on

the thesis that virtue is knowledge,59 or as

an argument for the unity of virtue.60Such

opposing views indicate that Plato's

dialectic dialogues remain a crux to the

interpreter. In the words of V. Goldschmidt: ". . . le dialogue, en tant que genre

litte'raire,reste encore 'a definir. Nous n'en

connaissons avec certitude ni la prehistoire,

ni le but, ou les buts ... ni les lois de

composition."'6' Since Goldschmidt wrote

these wordswe have studied severaltreatises

of Plato with the premise that the proper

105

approach to a Socratic dialogue must

take into consideration both the literary

genre and the philosophic tenets.62In fact,

the two facets of dramatic devices and

philosophic theories appear to intertwine,

with the literary techniques presenting

clues to the philosophic content of the

composition. The present study of the

Laches seems to substantiate our findings in

the Euthyphro,Lysis, Meno, Lesser Hippias,

and Greater Hippias. If our approach

is sound, it should serve to demonstrate

the genius of Plato both as a master

litterateur and a pre-eminent philosopher

even in his shorter compositions.63

WESTMINSTERCOLLEGE

NOTES

58. J. Burnet, Platonism (Berkeley, 1928), pp. 3-15; A. E.

Taylor, op. cit. (n. 9), p. 21; Wilamowitz, op. cit. (n. 34), p.

141; E. Hoffman, "Die literarischen Voraussetzungen des

Platonverstandnisses," Zeitschrift fur philosophische Forschung,11(1947), 465-80; A. Croiset, Platon: Oeuvrescompletes

(Paris, 1921), II, 88.

59. E. Horneffer, Platon gegen Sokrates (Leipzig, 1904),

pp. 35-38.

60. G. Grote, op. cit. (n. 2), I, 480; C. Ritter, op. cit.

(n. 26), I, 295-97.

61. "Sur le probleme du 'systeme' de Platon," Rivista

criticadistoria dellafilosofia, V (1950), 173, as cited by O'Brien,

op. cit. (n. 1), p. 135.

62. Cf. n. 42.

63. The comparison we have made between the Laches and

the Republic may pose a problem of chronology for some

scholars. For the present, however, without professing to

enter the debate of Plato's "development," we may cite

apropos an observation of Professor P.-M. Schuhl (ttudes

platoniciennes [Paris, 1960], p. 33): "D'abord les difficult6s

que pr6senteparfois le classementchronologique et qui avaient

6t6 longuement discut6es jadis (a propos du Phedre en particulier) ont 6t6 mises en nouvelle lumiere a propos de certains

problemes qui n'avaient pas 6t6 approfondis au meme point

jusque-la. Je pense notamment a la remarquable 6tude que

M. Joseph Moreau a publi6e dans la Revue des etudes

grecques de 1941: 'Sur le platonisme de l'Hippias majeur'cette oeuvre qu'on range g6n6ralementparmi les dialogues de

jeunesse, dont elle a l'allure, et oui l'on trouve pourtant des

conceptions g6n6ralementattribu6es a une p6riode beaucoup

plus avanc6e. Des lors, bien des questions se posent: Platon

a-t-il compos6 des 'dialogues de jeunesse' A une date plus

tardive? Avait-il d6ja, dans sa jeunesse, les id6es qu'il n'y

expose pas encore? On sait que Shorey a soutenu la these de

l'unit6 de la pens6e platonicienne. N'y aurait-il pas mieux a

faire que d'6tudierla succession chronologique des dialogues ?"

This content downloaded from 14.139.122.114 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 19:30:41 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Você também pode gostar

- Assignment 1Documento1 páginaAssignment 1Zakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- OnCampusProposedWorkDocumento1 páginaOnCampusProposedWorkZakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- Team10 Software Design Document v1.0Documento41 páginasTeam10 Software Design Document v1.0Zakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- Statistical EstimationDocumento17 páginasStatistical EstimationZakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- Sofware EngineeringDocumento4 páginasSofware EngineeringZakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- 4404 Notes Sim BMDocumento7 páginas4404 Notes Sim BMgeokaran1579Ainda não há avaliações

- Axioms EquiProbSpaces InclExclDocumento14 páginasAxioms EquiProbSpaces InclExclZakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- Daiict Busi Fin Vi 08Documento22 páginasDaiict Busi Fin Vi 08Zakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- Daiict Hm206 Busi Fin Srs 2014 Topic 1Documento6 páginasDaiict Hm206 Busi Fin Srs 2014 Topic 1Zakuta123Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Janice Hartman - ResumeDocumento3 páginasJanice Hartman - Resumeapi-233466822Ainda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Development (Prelim)Documento3 páginasCurriculum Development (Prelim)daciel0% (1)

- Drama in Education - Dorothy Heathcote: Drama Used To Explore PeopleDocumento2 páginasDrama in Education - Dorothy Heathcote: Drama Used To Explore Peopleapi-364338283Ainda não há avaliações

- Course Outline GSBS6001 Tri 1, 2020 (Newcastle City) PDFDocumento6 páginasCourse Outline GSBS6001 Tri 1, 2020 (Newcastle City) PDF陈波Ainda não há avaliações

- K to 12 Training Plan for Grade 9 Filipino TeachersDocumento4 páginasK to 12 Training Plan for Grade 9 Filipino Teacherszitadewi435Ainda não há avaliações

- Course Syllabus Eng 312Documento8 páginasCourse Syllabus Eng 312IreneAinda não há avaliações

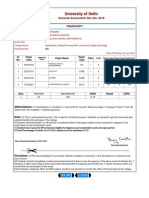

- University of Delhi: Semester Examination Nov-Dec 2018 TranscriptDocumento1 páginaUniversity of Delhi: Semester Examination Nov-Dec 2018 TranscriptVarun SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Reflection On Mock InterviewDocumento2 páginasReflection On Mock Interviewapi-286351683Ainda não há avaliações

- Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary CrisisDocumento210 páginasCritical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, and Planetary CrisisRichard Kahn100% (2)

- Career Planning For Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders Oct. 21-22Documento2 páginasCareer Planning For Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorders Oct. 21-22SyahputraWibowoAinda não há avaliações

- CHAPTER I WT Page NumberDocumento22 páginasCHAPTER I WT Page NumbershekAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding and Remembering Slang MetaphorsDocumento19 páginasUnderstanding and Remembering Slang MetaphorsabhimetalAinda não há avaliações

- Developmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistDocumento30 páginasDevelopmental Screening Using The: Philippine Early Childhood Development ChecklistGene BonBonAinda não há avaliações

- Examcourse Descr PDF 13133Documento1 páginaExamcourse Descr PDF 13133Ta Chi HieuAinda não há avaliações

- Redacted ResumeDocumento1 páginaRedacted ResumerylanschaefferAinda não há avaliações

- Resume - Ibrahim Moussaoui - Updated 2016Documento2 páginasResume - Ibrahim Moussaoui - Updated 2016api-228674656Ainda não há avaliações

- Echnical Ocational Ivelihood: Edia and Nformation IteracyDocumento12 páginasEchnical Ocational Ivelihood: Edia and Nformation IteracyKrystelle Marie AnteroAinda não há avaliações

- Portfolio - Artifacts and StandardsDocumento3 páginasPortfolio - Artifacts and StandardsMichele Collette-HoganAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningDocumento10 páginasThe Impact of Early Child Care and Development Education On Cognitive, Psychomotor, and Affective Domains of LearningPhub DorjiAinda não há avaliações

- Visible ThinkingDocumento2 páginasVisible Thinkingorellnairma88Ainda não há avaliações

- Shadow Puppet Project RubricDocumento2 páginasShadow Puppet Project Rubricapi-206123270100% (1)

- Victor Wooten - Texto Completo em Inglês PDFDocumento7 páginasVictor Wooten - Texto Completo em Inglês PDFCaio ReisAinda não há avaliações

- Observation-Sheet-9 JIMDocumento6 páginasObservation-Sheet-9 JIMJim Russel SangilAinda não há avaliações

- Pokhara University Examination System Effectiveness Challenges and SolutionsDocumento31 páginasPokhara University Examination System Effectiveness Challenges and SolutionsHari Krishna Shrestha100% (1)

- Eyetracking in Elearning - Challenges and Future ResearchDocumento4 páginasEyetracking in Elearning - Challenges and Future ResearchRazia AnwarAinda não há avaliações

- 2 PDFDocumento4 páginas2 PDFKashyap ChintuAinda não há avaliações

- History of Costume SyllabusDocumento3 páginasHistory of Costume Syllabuspaleoman8Ainda não há avaliações

- Mary Gavin Coaching LogDocumento5 páginasMary Gavin Coaching Logapi-211636402100% (1)

- VSO Activity BookDocumento127 páginasVSO Activity Bookcndy31100% (1)

- Organogram of Pakistan Railways.: Federal MinisterDocumento26 páginasOrganogram of Pakistan Railways.: Federal MinisterFarrukhupalAinda não há avaliações