Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

International Journal of Discrimination and The Law-2014-MacDermott-83-98-Art 4

Enviado por

Iulia DanaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Discrimination and The Law-2014-MacDermott-83-98-Art 4

Enviado por

Iulia DanaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

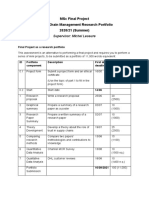

Article

Older workers and

extended workforce

participation: Moving

beyond the barriers to

work approach

International Journal of

Discrimination and the Law

2014, Vol. 14(2) 8398

The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1358229113520211

jdi.sagepub.com

Therese MacDermott

Abstract

Many countries have responded to the prevailing fiscal and demographic challenges by

introducing measures to extend the workforce participation of older workers. This

paper assesses the type of measures commonly utilized to extend labour force participation, using examples of legislative reforms and social policy initiatives in Australia, the

UK and other EU member states. It argues that these measures are principally aimed at

mandating or incentivising extended labour force participation, and lack a focus on

achieving substantive outcomes for older workers. This paper explores the type of

measures necessary to move beyond a barriers to work approach, with a particular

emphasis on promoting and sustaining the inclusion of older workers through strategies

that encourage employer engagement in ascertaining and addressing structural impediments facing older workers, that facilitate flexible work practices and that implement a

reasonable adjustments approach.

Keywords

Age, workforce participation, discrimination

Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University, Australia

Corresponding author:

Therese MacDermott, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia.

Email: therese.macdermott@mq.edu.au

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

84

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

Introduction

Increased longevity and declining fertility shape the demographic landscape in many

developed countries. An ageing population puts pressure on national pensions, social

security, health care and aged care systems. Declining fertility threatens efforts to maintain a broad tax base of working persons to meet these future costs, and generates associated concerns regarding skills shortages and competition for such labour. Over the last

decade many countries have sought to respond to these challenges by introducing a range

of measures to extend the workforce participation of older workers, with a view to reducing reliance on pensions and social security entitlements and to prolonging taxation contributions. While these measures are premised on the expectation that older workers will

be able to extend their workforce participation, there is no guarantee that employers

share this vision or will actively seek to employ or retain older workers.

There has been slow progress made in increasing participation rates of older workers

(Marin and Zaidi, 2007). Although employment rates for older workers have increased in

the last decade, the figures across all EU member states show that only three out of 10 in

the 6064 age cohort are in employment (European Foundation for the Improvement of

Living and Working Conditions, 2012). Despite the clear fiscal and demographic logic of

keeping workers engaged with the paid workforce for longer, the pervasive negative

stereotypes about the employability of older workers and concerns about their productive

capacity have not shifted to match the new policy agenda (Dadl, 2012; Patrickson and

Ranzijin, 2005: 730). There is also the related argument that workers themselves need

to accept the necessity of working longer (European Foundation for the Improvement

of Living and Working Conditions, 2013: 42).

Cultural norms and community expectations about the appropriate timing of an end

to workforce participation have often been constructed around pensionable age or mandatory retirement age. Changing those norms and expectations involves a range of different push and pull factors. Prospective retirement income is clearly a highly

influential factor, as well as health and physical capacity, working conditions and job

satisfaction. Setting aside these individual preferences, working longer becomes a

necessity where access to pensions and other retirement income is denied until an individual attains an extended age-based eligibility criteria. Alternatively, a more nuanced

approach is one that provides incentives that make working longer more attractive

financially, or imposes financial disincentives to early retirement. However, while

these approaches involve implementing a requirement or incentive for working longer,

they do not encompass a strategy to ensure that opportunities to work actually exist or

remain for older workers.

This paper begins with considering why the attribute of age presents particular challenges for workplace regulation. It then assesses the type of measures commonly

employed in developed countries1 to bring about extended labour force participation,

in particular using examples of legislative reforms and social policy initiatives in Australia, the UK and other EU member states. This paper identifies the principal focus

of these measures as being on overcoming or removing barriers to work, without due

regard to the need to ensure that opportunities for extended workforce participation actually exist. It also examines the limitations of pursing rights for older workers through an

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

85

equality framework. It argues that the shortfalls in the emerging regulatory framework

common to many developed countries are a consequence of the priority given to economic and fiscal considerations and a lack of focus on achieving substantive outcomes

for older workers. It also argues that the constrained nature of the equality protections

applicable to discrimination against older workers limits the effectiveness of the overall

regulatory approach. This paper concludes with a critique of the type of measures necessary to move beyond a barriers to work approach towards a strategy that aims to promote and sustain the inclusion of older workers.

The attribute of age

National legislation prohibiting age-based discrimination at work is relatively common,

particularly in EU member states since the adoption of the EU Employment Equality

Directive (Meenan, 2007: 59). Relevant International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions and associated recommendations also provide a basis for proscribing agerelated discriminatory treatment at work.2 Despite this framework, non-discrimination

principles are not often perceived as an adequate motivational factor for employers to

deal systemically with age discrimination or to implement pro-active measures. Dealing

with workplace age-related issues is more likely to be portrayed as an economic labour

market issue, rather than an equality issue (OCinneide, 2003: 199200). One academic

study concluded that the approach of some justices in the US was indicative of a view of

age discrimination as less salient a societal problem than other forms of bias (BisomRapp et al., 2011: 109). Age has an aspect of universalism that does not directly affect

other attributes covered by equality legislation, whereby all individuals are likely to

experience each age and perceived life-cycle stage. In addition, chronological age is

utilized in allocating and defining certain rights and responsibilities in specified circumstances; such as eligibility for voting, marriage and consent. This in turn provides some

validation for the use of age as a convenient shortcut in assessing individual capacity or

suitability. As a consequence, equality legislation as it applies to age discrimination is

often qualified by an extensive range of specific exceptions that are not present with

respect to other attributes.

Tough economic circumstances do little to advance the cause of redressing workplace

age discrimination, in particular as it applies to older workers. In times of economic

uncertainty and high youth unemployment there is additional pressure to favour younger

workers over an older generation,3 and retaining and sustaining older workers becomes

less of a priority (Parry and Harris, 2011: 6). In such circumstances the notion of intergenerational equity underpins the argument that older workers need to make room for

younger colleagues. This argument is fuelled by perceptions that older workers have had

a long period of workforce engagement and therefore should make way for younger

workers, and that institutions need new blood. In addition, older workers as a cohort

are regularly typecast are not well suited to the dynamic nature of the modern workplace

in which technological innovation and creativity predominate (Friedman, 2003: 191).

There is also a misconception that if older workers remain in employment, there are

fewer jobs for younger people (Bisom-Rapp and Sargeant, 2013); which is often referred

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

86

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

to as the lump of labor fallacy (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living

and Working Conditions, 2013: 8; OECD, 2011: 76; Walker, 2000).

During the recent recession in Europe, employment rates for older workers appear

to have been less affected than for younger workers (Beck, 2013: 259), although older

workers were more likely to find themselves in non-standard forms of employment

(European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions,

2012: 1). This is consistent with an academic study conducted on how older workers

fared in Australia, the UK and the US during the economic recession. It found that,

while actual participation rates may not have declined significantly for older workers,

forms of non-standard employment increased, thereby affecting the quality of work for

older workers (Bisom-Rapp et al., 2011). This study concluded that for many,

employment has become more fragile, inconstant, and insecure and this in turn

impacted on workers capacity to plan for a dignified retirement (Bisom-Rapp

et al., 2011: 48). Consequently, while the poor economic conditions in Europe of late

may have had a greater impact on employment rates for younger workers, they have

also contributed to further vulnerability for older workers in the form of more nonstandard employment arrangements.

Age also has a clear gender dimension. Challenging age restrictions in employment

has been characterized, at least in the US context, as the domain of white middleclass men (Friedman, 2003: 175182). Further, it has been suggested that women are

more likely to normalize the ageism they are subject to, based on their experiences

of gender-based discrimination (Thornton and Luker, 2010: 161). In Europe there has

been a narrowing of the gender gap for participation of older workers, but this varies

on a country-to-country basis (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and

Working Conditions, 2012). The time that women spend out of the paid workforce, or in

a reduced form, affects employment opportunities, contributions to retirement savings

and pay equity. The caring responsibilities that many women have for young children

are often revisited in later life in the form of responsibilities for parents, partners or children with disabilities in need of care and support. Decision-making by older women with

respect to maintaining or remaining in paid employment is also seen as more likely to be

affected by their domestic circumstances (Loretto and Vickerstaff, 2013; Vickerstaff

et al., 2008).

Extending labour force participation through pension reforms

One of the bluntest instruments for influencing the timing of an end to workforce participation is to simply change age-based eligibility for pensions. This has the dual consequence of delaying responsibility for paying pension entitlements and extending

the period of taxation contribution. The ageing of populations presents challenges for the

long-term sustainability of pension schemes in many countries (European Commission,

2012). Recent financial instabilities in Europe have put additional pressure on the adequacy of such schemes. Many countries are currently implementing or actively contemplating a change in the pension eligibility age that will move incrementally from 65 to 67

over an extended phase-in period. There is related pressure to raise the preservation age

for access to occupational pension schemes.

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

87

Other types of reforms include the phasing out of pension schemes that rely solely on

length of service and are not age-dependent. In addition, the capacity to access early

retirement schemes has been restricted in many countries, although it still remains as

a practice in some countries as a tool in implementing restructuring and redundancies

(European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2013:

10). In addition, the adverse taxation treatment of early retirement payments can diminish the appeal of such schemes. Rules relating to social welfare entitlements can also be

tightened to limit the capacity of individuals to access sickness or disability benefits as a

form of substitute payment prior to reaching the age pension threshold. Some countries

have taken steps to try and reduce the fiscal burden of their pension schemes by changing

from defined benefit to defined contribution, as well as encouraging a change in the mix

of public pensions and privately funded occupational pension schemes.

Rather than imposing disincentives, an alternative reform is one that creates positive financial incentives for extended workforce participation. Relaxing the rules on

access to pensions, occupational pensions schemes and benefits payments, while maintaining some form of employment, is such an example. Some schemes reward delaying

retirement beyond the eligibility age with increased benefits (Marin and Zaidi, 2007:

77). Taxation systems can also provide favourable tax treatment for personal retirement savings or tax deductibility for additional voluntary contributions to occupational

pension schemes.

However, these approaches do not address the vexing question of whether the mandated or desired extended workforce participation will be available to older workers.

Denying access to pension entitlements until the new age criterion is met merely imposes

a compulsion to work longer, rather than a tangible opportunity for continuing workforce

participation. Without adequate attention to generating those opportunities there is the

potential for increased dependence on forms of social welfare and the risk of poverty for

older workers not able to access retirement income. While equality legislation aims to

create an equality of opportunity for older workers in seeking or retaining such opportunities for continuing workforce participation, in its current manifestation it is of limited

utility, as discussed below.

Facilitating extended labour force participation through equality protections

The proscription of age-based discrimination in employment is seen as a necessary prerequisite for extending the workforce participation of older workers in many countries,

and national legislation prohibiting age-based discrimination at work is relatively common. Additional protection can also be provided against discriminatory dismissals or

redundancy arrangements through other forms of employment protection legislation.

However, there is evidence indicating that some countries in Europe still permit employers

to terminate employment on notice at a nominated age (European Commission, 2011: 6).

An equality rights framework can serve both a normative function as well as providing a discrete avenue for redressing individual complaints. In common with most

complaints-based equality legislation, pursuing specific incidences of workplace age discrimination is challenging. For example, research on this subject in Australia indicates

that not one case has been successfully litigated under the national age discrimination

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

88

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

legislation, attributable to a range of factors including shortcomings of the legislative

scheme, limitations in access to justice, an over-emphasis on conciliated outcomes and

difficulties of proof (MacDermott, 2013). In addition, remedies that are focused on compensation rather than reinstatement offer less utility to older workers, for whom the loss

of a job results in a longer-than-average period of unemployment. In this context, the

capacity for strategic enforcement by a well-resourced regulatory agency is highly

significant.

Unlike other relevant attributes, the protection provided against age discrimination is

specifically qualified in many national systems by the concepts of justifiability or reasonableness. Under the terms of the relevant European Directive,4 national legislative

schemes can provide for differences in treatment on the grounds of age that are objectively and reasonably justified by a legitimate aim, and where the means adopted is considered appropriate and necessary. The interpretation of justification in the context of age

discrimination has been characterized as not necessitating exceptional circumstances,

and permitting countries to use a broader range of legitimate aims that are not confined

to matters of public interest (European Commission, 2011: 5). European case law indicates that states are not required to draw up a list of differences in treatment that might be

justified.5 The aims of a fair distribution of employment opportunities and facilitating

younger people finding work, particularly where there is high youth unemployment, are

potentially justifiable.6 The jurisprudence in this area acknowledges intergenerational

fairness and dignity as legitimate aims.

In the UK, what is encompassed by the concepts of intergenerational fairness and

dignity in the context of forced retirement was considered in Seldon v Clarkson Wright

and Jakes (A Partnership). The Supreme Court stated that intergenerational fairness

can include facilitating access to employment by young people, enabling older people to remain in the workforce, sharing limited opportunities to work in a particular

profession fairly between the generations and promoting diversity. The Court also

concluded this extended to avoiding the need to dismiss older workers on the grounds

of incapacity or underperformance, thus preserving their dignity and avoiding humiliation, and avoiding the need for costly and divisive disputes about capacity or underperformance. However, the Court did go on to consider the need for this to be viewed in

the context of the particular employment, and that the means chosen must be appropriate.

The matter was then sent back to the Tribunal, which found that the forced retirement

was justified as a proportionate means of achieving workforce planning, ensuring that

partnership opportunities existed for junior staff within a reasonable timeframe, and curtailing the need to remove partners through performance management.7 The Tribunal

viewed the retirement age as providing an acceptable balance between the needs of the

firm and the individual partner, and one that Seldon had agreed to in advance within the

terms of the partnership agreement. Ironically, little dignity seemed to be preserved after

years of litigation over the issue. Along similar lines, evidence from the US indicates that

the reasonableness of a policy or practice that adversely impacts on the basis of age is

more likely to be found to be justifiable than in the case of any other ground (BisomRapp et al., 2011: 107109).

The notion of the justifiable sharing of employment opportunities between the generations, and avoiding undignified disputes over capacity and performance of older

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

89

workers, are strong themes running through much of the relevant case law. As a consequence of this approach the effectiveness of prohibitions on age discrimination is

limited in terms of protecting older workers, particularly in relation to labour market

policies and initiatives that seek to create job opportunities for younger workers. This

is exacerbated where the proportionality question is focused on the application of a

particular rule or retirement practice in broad terms, rather than as it applies to the particular individual in question and his or her need or desire to work longer (Vickers and

Manfredi, 2013). The capacity of equality legislation to promote and sustain the

employment of older workers is as a consequence constrained by the justifiability of

various policies and practices that override the equality guarantee otherwise available

to individual older workers.

Prohibiting mandatory retirement

One particular form of workplace age discrimination that has been specifically targeted

in many countries is mandatory retirement at a specified age. International comparisons

indicate that abolishing mandatory retirement age is an increasing common practice

(Wood et al., 2010), although some countries retain fixed age limitation for certain designated categories of employment, such as judicial or military personnel. The abolition

of mandatory retirement reflects a mix of motives; including addressing demographic

change, ensuring the fiscal sustainability of pension system and on-going labour supply,

as well as concerns for equality of opportunity and fairness (see, for example, the UKs

Department for Business Innovation and Skills and Department for Work and Pensions,

2010). The dignity argument has been invoked in this context to argue that a retirement

age allows for a dignified departure at a fixed age, rather than the need to address declining competence and capacity. But such an argument is premised on the assumption that

such a decline is inevitable and universal, thereby reinforcing the prevailing negative

stereotypes (Bisom-Rapp and Sargeant, 2013; Sargent, 2010: 250). In addition, it suggests that all performance management systems are inherently flawed. It also does little

to advance the dignity of those who are ready, willing and able to work beyond that fixed

age. In fact, an approach based on dignity should be premised on individual assessment

and on equal concern and respect for the individual (Alon-Shenker, 2012). Finally, it

ignores the possibility of an alternative approach based on responding to or accommodating any limitations through reasonable adjustments that would enable an older worker

to perform the inherent requirements of the job in question.

The combination of outlawing mandatory retirement and setting a threshold pension

age means that voluntary workforce participation is permitted beyond the age pension

threshold. Like other initiatives in this area it creates the expectation of continuing

employment, but does not address how to facilitate the retention and hiring of older

workers in this new environment. While there are examples of good age management

policies and practices in some European enterprises and elsewhere (Taylor, 2006), there

is a need to convince a broader range of employers that older workers are suited to contemporary work practices and demands, and that an age-diverse workforce is more sustainable in the current demographic context (European Foundation for the Improvement

of Living and Working Conditions, 2012: 9).

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

90

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

Transcending barriers to work

In the preceding sections, this paper has dealt with how legislation and social policy can

be designed to make working longer a necessity, a practical reality or an attractive

option. However, the fact that these legislative changes and policies are premised on

extended workforce participation by older workers does not necessarily mean that

employers will adjust their recruitment and retention strategies accordingly (Patrickson

and Ranzijin, 2005: 733). The demographic realities of an ageing population inevitably

puts pressure on employers to rethink their views about older workers, and social policies

are increasingly highlighting the business case for embracing an older workforce. An

age-diverse workforce is presented as a way of ensuring intergenerational cohesion,

knowledge transfer and succession planning (International Labour Organization, 2009:

8). However, it is interesting to note that the rights-based perspective of facilitat[ing]

equal participation of all in society, based on equal concern and respect for the dignity

of each individual (Fredman, 2003: 21), is rarely the rationale employed.

What influences a particular worker to formally disengage from workforce participation is highly variable, and dependent to a large degree on individual circumstances. The

common determinants include financial security, health and disability and caring responsibilities. Added to these are factors such as working conditions, employers reluctance

to employ or retain older workers, pervasive negative attitudes to older workers in the

workplace, and the consequent demoralization of older workers (European Foundation

for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2013: 23; Marin and Zaidi,

2007: 8182). This can be compounded by external practices of organizations such as

recruitment agencies that perform a gatekeeping function in preventing older workers

accessing employment opportunities. And whether that disengagement is preceded by

a phased transition, a reduction in responsibilities or a period of non-standard employment also varies. An Australia study in this area concluded that most workers would

prefer to retire early, while few are able to work as long as they expect or need to work

(National Seniors Australia, 2009).

One obvious approach is for programs to directly fund or subsidize the employment of

unemployed older workers (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and

Working Conditions, 2013: 24). Alternatively, more indirect incentives can be offered

to employers for employing older workers through tax credits or offsets (Marin and

Zaidi, 2007: 84). While these measures can have the immediate effect of creating job

opportunities for older workers, they can compound negative perceptions about older

workers by creating the impression that there must be a problem with older workers

otherwise an employer would not need to be paid to employ them (Patrickson and Ranzijn, 2005: 37). Moreover, it is necessary to look closely at the retention of such workers

and their long-term job prospects.

Equality legislation clearly plays an integral role in providing older workers with an

avenue for redress, and its supporting educational and promotional campaigns can over

the long term contribute to bringing about attitudinal change to the employment and

retention of older workers. However, other targeted measures are required to move from

an expectation of extended workforce participation for older workers to actively facilitating such participation. The following discussion examined three approaches that seek

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

91

to move beyond the barriers to work approach through strategies that focus on how an

organization can ascertain and address structural impediments within its workforce, the

potential for flexible work practices to facilitate extended workforce participation, and

the need for a reasonable adjustments approach to the attribute of age.

An employment equity approach

A significant problem with ascertaining whether discrimination in employment is

impacting on the employment opportunities of older workers is having reliable employment data to work with (Ghosheh, 2008). An assessment of the existing and potential

employment opportunities of older workers necessitates at the very least data on the age

profile of the workforce, the forms of employment engaged in by older workers and their

working conditions. It also requires engagement in workforce planning to determine

future workforce needs, likely workforce profiles and opportunities for varying forms

of employment. Whether this data is available is dependent on the reporting obligations

imposed on, or voluntarily undertaken by, employers.

One source of such information is where equal employment opportunity (EEO) mechanisms exist for reporting on workplace practices and procedures. While reporting on the

gender composition of the workforce may be a relatively common practice, few countries

have adopted an employment equity approach with respect to other criteria. In Canada, the

Employment Equity Act8 mandates the use of a scheme that encompasses women, Aboriginal

peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities. Northern Ireland uses an

affirmative action approach that monitors labour force segregation on the basis of religious

affiliation, is based on reviews of workplace composition, and has the capacity to require that

remedial action be taken.9 In the Australian context, the advocacy body National Seniors

Australia, drawing comparisons to recent legislative developments on workplace gender

equity, has questioned why no equivalent reporting requirements are imposed with respect

to the proportion of older workers and the actions by employers to enhance employment

opportunities for older workers (National Seniors Australia, 2009: 22).

Many are put off the idea of an employment equity approach where it takes the form

of positive action that sets targets or quotas for the employment of specific groups.

However, the prevailing regulatory model tends to favour a light touch approach

that focuses on employers reviewing and reporting on their employment practices

with respect to recruitment, training, promotion and redundancy, with an escalation to

auditing or contract compliance sanctions only for those organizations where underrepresentation continues to be problematic (see Hepple et al., 2000: 6472). In the

context of older workers, public and private sector employers, whose workforce meets

a certain threshold number of employees, could be required to review and report on the

composition of their workforce in terms of age groupings, the associated employment

status and working conditions. In addition, the process could focus specifically on

recruitment and redundancy practices with respect to older workers, and their access

to training and promotion. In this way the process would be designed to identify structural barriers impeding the opportunities of older workers, as a means of determining the

necessary steps to address such barriers. Such a process has the potential to promote

transparency around the employment practices pertaining to older workers and to

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

92

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

facilitate the development of targeted measures to enhance opportunities for older workers. It is premised on the view that employers once presented with the information will

take the opportunity to reflect and improve on their practices, which may be overly optimistic for the full spectrum of employers. But as a form of light-touch regulation, it is

also premised on the understanding that agency monitoring and oversight is involved,

and that the absence of improved outcomes would necessitate a more rigorous compliance response (McCrudden, 2007; McCrudden et al., 2009).

As an alternative to approaching employment equity through general obligations, collective bargaining arrangements can be harnessed to achieving greater transparency

regarding employment practices and to facilitate measures to enhance employment

opportunities for older workers. An example of this is the obligation imposed on enterprises in France that have over 50 employees to enter into collective agreements that

made provision for action plans on the employment of older workers, with noncompliance subject to a financial penalty (Gineste, 2012: 4). Such agreements must set

objectives for recruitment and on-going employment, specify measures for achieving

these objectives and provide some form of monitoring mechanism. The evidence suggests that by 2010 80% of eligible companies were covered by such agreements, but that

the economic crisis has lessened the priority given to this issue (European Foundation for

the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2013: 1617). A variant on this

approach is the example of a collective agreement concluded in the chemical industry

in Germany that commits employers in the industry to analysing their staff structure,

qualifications, rates of sick leave and other demographic details as a way of informing

the measures to be taken by an enterprise (European Foundation for the Improvement

of Living and Working Conditions, 2013: 1920).

Flexible work practices

It is important to acknowledge that not all older workers want or need flexible work practices in order to maintain or sustain their workforce participation, and the form in

which they might seek flexibility is likely to be diverse. However, where sought it has

the capacity to have a positive impact on achieving the stated goal of extending workforce participation, as well as contributing to a broader distribution of employment

opportunities. Research in the UK shows that flexibility in working arrangements for

those with health concerns or caring responsibilities is a desirable option (Vickerstaff

et al., 2008: 5). Many countries facilitate this process in circumstances where workers

are returning from parental leave, and this has been extended in some countries to

cover other forms of carers responsibilities. This clearly has a gendered aspect to it,

but can also have an older worker dimension as well. In the Australian context it has

been found that the prospect of a worker needing to provide care to another increases

with age and that the majority of carers are aged 45 years or over (Australian Bureau of

Statistics, 2009: 10).

Some jurisdictions provide a right to request flexible working arrangements to all

employees as a way of retaining staff, increasing commitment and improving productivity A broader right to request available to all employees can mainstream the concept of

flexibility. This approach has been adopted in some EU counties and is being

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

93

contemplated in some other jurisdictions (HM Government UK, 2011; Australian

Human Rights Commission, 2013: 27). Commonly the rights aspect of the request for

flexible working arrangements is limited. The refusal of a request by an employer usually must be grounded in a justifiable business case, with such a refusal justiciable in

some jurisdictions but not others. In the Australian context, an agency evaluation of the

statutory right of parents to request flexible work arrangements found relatively low rates

of refusal (Australian Government, 2012).

In 2013 the right to request flexible working arrangements under Australian labour

laws was expanded to specifically include employees who are 55 or older, with a refusal

by the employer only available on the basis of reasonable business grounds.10 This

right is not contingent on their status as a carer, but can be triggered purely on the basis

of reaching the stipulated age threshold. Like other formulations of the right to request

flexible work arrangements, the right is not justiciable, and there is no statutory

mechanism for formally challenging a refusal. While a number of governmentcommissioned reports have lobbied for this extension of the scheme (Advisory Panel

on the Economic Potential of Senior Australians, 2011: Rec 15), others have been concerned that formulating the right to request based around the attribute of age per se,

rather than caring responsibilities, could contribute to on-going discriminatory practices against older workers and exacerbate negative stereotypes (Australian Law

Reform Commission, 2013: [4.44][4.52]). The expansion of the statutory scheme to

include employees who are 55 or older does mean that for older workers who are seeking greater flexibility as a way of sustaining their workforce participation there is an

established mechanism for pursuing this possibility. It has the potential to allow for

greater dialogue on transitions to retirement and retirement preferences. This approach

also has the potential to facilitate some intergenerational redistribution of employment

opportunities, knowledge transfer and succession planning, while allowing older workers the dignity of choice as to the level and form of continued workforce participation.

Pension reforms referred to above, that allow access to pensions, occupational pensions schemes and benefits payments while maintaining a limited form of on-going

employment, work in unison with this approach.

A reasonable adjustments approach

Another pivotal consideration is whether the obligation to make reasonable adjustments

to accommodate the capacity and circumstances of an individual that applies in the disability discrimination context should be extended to other protected attributes such as

age. Canada is one of the few jurisdictions where this extended obligation operates. In

that context, the duty to accommodate has been described as a standard that must

accommodate factors relating to the unique capabilities and inherent worth and dignity

of every individual, up to the point of undue hardship.11 Recent debate over reforms to

the overall framework of equality legislation in Australia raised the prospect of a duty to

make reasonable adjustments applying to all attributes, and many stakeholders supported

this approach on the basis of clarity and consistency between attributes (Discrimination

Law Experts Group Submission, 2011: 12). If a duty to make reasonable adjustments

was applicable in the context of age discrimination, an employer would need to look

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

94

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

at whether changes could be made or criteria varied to accommodate the situation of an

older worker. Along similar lines to the disability context, this obligation may be subject

to the qualifiers of reasonableness and unjustifiable hardship.

If we look at the type of common perceptions that tend to discourage employers from

hiring or retaining older workers, concerns regarding capacity to undertake the work feature prominently, whether or not this is a misconceived perception or an actuality. A duty

to make reasonable accommodations with respect to the attribute of age would move the

focus away from the exclusion of older workers based on perceived incapacity, with the

focus instead being on facilitating an individuals actual capacity for undertaking

the work in question. Given the policy imperative of extending workforce participation,

it is the long-term sustainability of jobs in the context of an ageing workforce that must

be pursued. The issue of sustainability has been a focal point of the public debate surrounding pension reforms, but is also a crucial aspect in the retention of older workers.

It necessitates an examination of existing working conditions and the implementation of

appropriate modifications to job design and working practices (Eurofound, 2012). The

sustainability of work encompasses the specific conditions under which the work is

undertaken, the nature and variability of the work itself, span of hours and work-life balance. However, one distortion of the sustainability concept that does need to be challenged is the version that advocates that the employment of older workers is only

sustainable if lower wages are payable.

Another prevalent stereotype that works against the hiring or retention of older workers is that older workers are perceived as not willing or able to adapt to new processes,

and that their skills are not well suited to the dynamic nature of the modern workplace.

Qualitative research in this area indicates that few learning and development opportunities are made available to older workers (Beck, 2012), with negative stereotyping and

views on return on investment arguments operating to exclude many older workers from

such opportunities (Canduela et al., 2012). Training and re-training can be encouraged

through tax incentives or subsidies, and where older workers do have the skills based

on experience, but lack the formal qualifications attesting to this achievement, appropriate measures should be set in place to recognize this in accreditation. But it is often the

absence of any offer of training or opportunity to develop new skills that is the problem,

which then in turn becomes the justification for the failure to hire or retain an older

worker. A reasonable adjustments approach would shift the focus to what training and

development opportunity could be provided to an individual older worker, and in what

form, that would enable them to secure and sustain workforce participation.

Conclusion

The oceans of diversity-related age discrimination messages, which use clever titles like

grey matters or turning grey into gold, do not necessarily change deeply engrained

attitudes to life-cycle defined workforce participation. While the demographic actualities mean that employers will at some point inevitably need to accept the greying reality, many still perceive younger people as being more adaptable and better able to

succeed in modern working life. Nor will employers necessarily be sold on the equality

argument. But employers are increasing influenced by the business case for effective age

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

95

management policies that can facilitate intergenerational cooperation, knowledge transfer and succession planning. Decisions by older workers about extending workforce participation, while predicated on factors such as affordability of retirement, health and

carers responsibilities, are influenced by the availability of flexible work practices,

phased transitions to retirement and the inclusiveness of on-going training and development opportunities. Addressing factors that impact on the sustainability of working conditions is also significant. Legislation and social policy can tinker with the age-based

eligibility for pensions and benefits as well as other financial incentives and disincentives. However, the maintenance of, and commitment to, genuine employment opportunities for older workers, unfettered by negative perceptions of age, must be a pivotal part

of the broader solution to the demographic and fiscal challenges.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or

not-for-profit sectors.

Notes

1. For developing countries, where there is often a younger population, the problem tends to be

the absence of the supporting social infrastructure of developed social security systems and

retirement income schemes.

2. ILO Convention on Discrimination (Employment and occupations) Conventions 1958

(N0111), ILO Older Workers Recommendations 1980 (No162).

3. See recent reports of plans in Greece to replace 15,000 public servants with younger candidates: see http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-22328710

4. EU Employment Equality Directive, Article 6.

5. R (Age Concern England) v Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform

Case C-388/07 [2009] ICR 1080. See also Petersen v Berufungsausschuss fur Zahnarzte fur

den Bezirk Westfalen-Lippe, Case C-341/08, [2010] 2 CMLR 830; Wolf v Stadt Frankfurt

am Main, Case C-229/08 [2010] 2 CMLR 849.

6. Rosenbladt v Oellerking GmbH, Case C-45/09 [2011] CMLR 101.

7. ET/1100275/07.

8. 1995 SC c 44 (Canada) c2.

9. Fair Employment (Northern Ireland) Act 1989 (NI).

10. Fair Work Amendment Act 2013 (Cth).

11. British Columbia (Public Service Employment Relations Commission) v British Columbia

Government and Service Employees Union [1999] 3 SCR 3 at [62].

References

Advisory Panel on the Economic Potential of Senior Australians (2011) Realising the Economic

Potential of Senior AustraliansTurning Grey into Gold. Parkes, NSW: Commonwealth of

Australia.

Alon-Shenker P (2012) The unequal right to age equality. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 25(2): 243282.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, Cat No 4430.0 10.

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

96

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

Australian Government (2012) Towards More Productive and Equitable Workplaces: An Evaluation of the Fair Work Legislation. Canberra, Department of Education, Employment & Workplace Relations.

Australian Human Rights Commission (2013) Investing in care: Recognizing and valuing those

who care. Vol. 1. Research Report, Sydney, NSW.

Australian Law Reform Commission (2013) Access all ages Older workers and Commonwealth

laws. ALRC Report no.120, Sydney, NSW.

Beck V (2012) Employers views of learning and training for an ageing workforce. Management

Learning 116.

Beck V (2013) Employers use of older workers in the recession. Employee Relations 35(3):

257271.

Bisom-Rapp S, Frazer A and Sargeant M (2011) Decent work, older workers, and vulnerability in

the economic recession: A comparative study of Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United

States. Employee Rights and Employment Policy Journal 15: 43121.

Bisom-Rapp S and Sargeant M (2013) Diverging doctrine, converging outcomes: Evaluating

age discrimination laws in the United Kingdom and the United States. Loyola University

Chicago Law Journal 44: 717770.

Canduela J, Dutton M, Johnson S, et al. (2012) Ageing, skills and participation in work-related

training in Britain: assessing the position of older workers. Work Employment & Society

26(1): 4260.

Dadl J (2012) Too old to work, or too young to retire? The pervasiveness of age norms in Western

Europe. Work Employment and Society 26(5): 755771.

Department for Business Innovation and Skills and Department for Work and Pensions (2010)

Phasing out the Default Retirement Age: Consultation document. July 2010, London, UK.

Discrimination Law Experts Group Submission (2011) Consolidation of Commonwealth Antidiscrimination Laws. Available at www.ag.gov.au/consultations/pages/consolidationofcommonwealthanti-discriminationlaws.aspx (accessed August 2013).

Eurofound (2012) Sustainable Work and the Ageing Workforce. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

European Commission (2011) Age and Employment. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice/discrimination/files/age_and_employment_en.pdf (accessed August 2013).

European Commission (2012) White paper: An agenda for adequate, safe and sustainable pensions. Report no. 16.2.2012 COM (2012) 55 final. Brussels.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2012) Employment

Trends and Polices for Older workers in the recession. Report no. EF/12/35/EN. Available at:

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2012/35/en/1/EF1235EN.pdf (accessed August 2013).

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2013) Role of governments and social partners in keeping older workers in the labour market. Available at:

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2013/23/en/1/EF1323EN.pdf (accessed August 2013).

Fredman S (2003) The age of equality. In: Fredman S and Spencer S (eds) Age as an Equality

Issue. Oxford: Hart Publishing, pp. 2169.

Friedman L (2003) Age discrimination law: Some remarks on the American experience. In Fredman S and Spencer S (eds) Age as an Equality Issue. Oxford: Hart Publishing, pp. 175194.

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

MacDermott

97

Gineste S (2012) EEO Review: Employment policies to promote active ageing. European Employment

Observatory. Available at: http://www.eu-employment-observatory.net/resources/reviews/

France-EEO-GJH-2913.pdf (accessed August 2013).

Ghosheh N (2008) Age discrimination and older workers: Theory and legislation in comparative

context. Conditions of Work Employment Series No. 20. Geneva: ILO.

Hepple B, Coussey M and Choudhury T (2000) Equality: A new framework: Report of the independent review of the enforcement of UK anti-discrimination legislation. Oregon: Hart

Publishing.

HM Government UK (2011) Consultation on Modern Workplaces. ii) Flexible working.

Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/

31549/11-699-consultation-modern-workplaces.pdf (accessed August 2013).

International Labour Organization (2009) Report on the ILO symposium on business responses to

the demographic challenges. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Loretto W and Vickerstaff S (2013) The domestic and gendered context for retirement. Human

Relations 66(1): 6586.

MacDermott T (2013) Resolving federal age discrimination complaints: where have all the complainants gone? Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal 24(2): 102111.

Marin B and Zaidi A (2007) Trends and priorities of ageing policies in the UN-European region.

In: Marin B and Zaidi A (eds) Mainstreaming ageing: Indicators to monitor sustainable

policies. Ashgate, Burlington.

McCrudden C (2007) Equality legislation and reflexive regulation: A response to the Discrimination Law Reviews consultation paper. Industrial Law Journal 36: 255266.

McCrudden C, Muttarak R, Hamill H, et al. (2009) Affirmative action without quotas in Northern

Ireland. Equal Rights Review 4: 714.

Meenan H (2007) Reflecting on age discrimination and rights of the elderly in the European Union

and the Council of Europe. Maastricht J. Eur. & Comp. L. 14: 3982.

National Seniors Australia (2009) Experience works: the mature age employment challenge.

Available at http://www.productiveageing.com.au/userfiles/file/ExperienceWorks_FINAL_

WEB.pdf (accessed August 2013).

OCinneide C (2003) Comparative European perspectives on age discrimination legislation. In:

Fredman S and Spencer S (eds), Age as an Equality Issue. Oxford: Hart Publishing, pp.

195217.

OECD (2011) Pensions at a Glance 2011: Retirement-income Systems in OECD and G20 Countries. OECD Publishing. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2011-en

(accessed August 2013).

Parry E and Harris L (2011) The Employment Relations Challenge of an Ageing Workforce. ACAS

Future of Workforce Relations discussion paper series. Available at http://www.acas.org.uk/

media/pdf/e/p/The_Employment_Relations_Challenges_of_an_Ageing_Workforce.pdf (accessed

August 2013).

Patrickson M and Ranzijin R (2005) Workforce ageing: The challenge for 21st century management. International Journal of Organizational Behaviour 10(4): 729739.

Sargent M (2010) The default retirement age: Legitimate aims and disproportionate means. Industrial law Journal 39(3): 244263.

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

98

International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14(2)

Taylor P (2006) Employer Initiatives for an Ageing Workforce in the EU15. Luxembourg:

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Available at:

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2006/39/en/1/ef0639en.pdf (accessed August 2013).

Thornton M and Luker T (2010) Age discrimination in turbulent times. Griffith Law Review 19(2):

141171.

Vickers L and Manfredi S (2013) Age discrimination and retirement: Squaring the circle. Industrial Law Journal 42(1): 6174.

Vickerstaff S, Loretto W, Billings J, et al. (2008) Encouraging labour market activity among 60

64 year olds, Research report no. 531. Norwich, UK: Department for Work and Pensions.

Walker T (2000) The lump-of-labor case against work-sharing: Populist fallacy or marginalist

throwback? In: Golden L and Figart D (eds) Working Time: International Trends, Theory and

Policy Perspectives. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 196211.

Wood A, Robertson M and Wintersgill D (2010) A Comparative review of international

approaches to mandatory retirement. Research report no. 674, Department for Work and

Pensions, Norwich, UK.

Downloaded from jdi.sagepub.com at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on November 10, 2015

Você também pode gostar

- ProQuestDocuments 2016-02-29Documento5 páginasProQuestDocuments 2016-02-29Iulia DanaAinda não há avaliações

- Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources-2007-Shacklock-151-67 - Art 1Documento17 páginasAsia Pacific Journal of Human Resources-2007-Shacklock-151-67 - Art 1Iulia DanaAinda não há avaliações

- Research On Aging 2014 Mercan 557 67 Art 2Documento11 páginasResearch On Aging 2014 Mercan 557 67 Art 2Iulia DanaAinda não há avaliações

- Listening 2Documento5 páginasListening 2Iulia DanaAinda não há avaliações

- Product Information: Synpower™ Motor Oil Sae 5W-40Documento2 páginasProduct Information: Synpower™ Motor Oil Sae 5W-40Iulia DanaAinda não há avaliações

- Body science listening unitDocumento2 páginasBody science listening unitIulia Dana100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- English BiwaterDocumento48 páginasEnglish BiwaterChen Yisheng100% (1)

- 2013 Overview and 2012 Annual Report of The Aspen InstituteDocumento45 páginas2013 Overview and 2012 Annual Report of The Aspen InstituteThe Aspen InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- DeforestationDocumento27 páginasDeforestationRabi'atul Adawiyah Ismail100% (1)

- Grace Warne - Research ProposalDocumento7 páginasGrace Warne - Research ProposalMatthew BradburyAinda não há avaliações

- Undp Rvca Teknaf Ukhia 2019Documento48 páginasUndp Rvca Teknaf Ukhia 2019Deannisa Dea HilmanAinda não há avaliações

- College of Arts and Sciences Instructor'S InformationDocumento12 páginasCollege of Arts and Sciences Instructor'S Informationkresta padillaAinda não há avaliações

- SCM Research Portfolio Summer 2021Documento10 páginasSCM Research Portfolio Summer 2021Dj KhaledAinda não há avaliações

- Reducing Greenhouse Effect Through Bioclimatic Building DesignDocumento17 páginasReducing Greenhouse Effect Through Bioclimatic Building DesignAnson Diem100% (1)

- Friendship Cube JournalDocumento5 páginasFriendship Cube JournalGraeme KilshawAinda não há avaliações

- WHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY - Richard HeinbergDocumento12 páginasWHAT IS SUSTAINABILITY - Richard HeinbergPost Carbon InstituteAinda não há avaliações

- LIFE Food & Biodiversity - FactSheet - Sugarbeet - OnlineDocumento16 páginasLIFE Food & Biodiversity - FactSheet - Sugarbeet - OnlineMohammad KhaledAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainbility 5eDocumento281 páginasSustainbility 5eRdy SimangunsongAinda não há avaliações

- UN SG Roadmap Financing The SDGs July 2019Documento67 páginasUN SG Roadmap Financing The SDGs July 2019Korean Institute of CriminologyAinda não há avaliações

- Study On Corossion Rate On Rebar in Concrete With STP Water Using Half-Cell PotentiometerDocumento55 páginasStudy On Corossion Rate On Rebar in Concrete With STP Water Using Half-Cell Potentiometerdineshkumar rAinda não há avaliações

- WWOOF India Organic Farms GuideDocumento134 páginasWWOOF India Organic Farms GuideK AnjaliAinda não há avaliações

- Batteries Europe Strategic Research Agenda December 2020 1Documento75 páginasBatteries Europe Strategic Research Agenda December 2020 1Mansour Al-wardAinda não há avaliações

- English For Academic and Professional Purposes: Language Used in Academic TextsDocumento21 páginasEnglish For Academic and Professional Purposes: Language Used in Academic TextsElla Canonigo CanteroAinda não há avaliações

- Eco Mock Test SPCC PDFDocumento2 páginasEco Mock Test SPCC PDFLove RandhawaAinda não há avaliações

- Hilton ReportDocumento16 páginasHilton ReportXuân Phong BùiAinda não há avaliações

- PaheDocumento10 páginasPaheArnav ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- NCE100 Gold Book PDFDocumento60 páginasNCE100 Gold Book PDFAnonymous kRIjqBLkAinda não há avaliações

- Some People Believe That The Rapid Increase in Population These Days Is Unsustainable and Will Eventually Lead To A Global CrisisDocumento4 páginasSome People Believe That The Rapid Increase in Population These Days Is Unsustainable and Will Eventually Lead To A Global CrisisAmir Raza FscAinda não há avaliações

- Transcending EconomiesDocumento6 páginasTranscending Economiespiyush saxenaAinda não há avaliações

- Stockholm City Plan Guide Towards Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento42 páginasStockholm City Plan Guide Towards Sustainable Developmentvasu10Ainda não há avaliações

- Rehau Guide For Specifiers and Architects PDFDocumento76 páginasRehau Guide For Specifiers and Architects PDFN.E.G.Ainda não há avaliações

- GS4 FinalDocumento57 páginasGS4 FinalRavindraKrAinda não há avaliações

- Applying Collocation Themes in IELTS WritingDocumento40 páginasApplying Collocation Themes in IELTS WritingMai NgọcAinda não há avaliações

- Construction Procurement Policy overviewDocumento12 páginasConstruction Procurement Policy overviewTaha MadraswalaAinda não há avaliações

- JSMS TemplateDocumento15 páginasJSMS TemplateUsman EpendiAinda não há avaliações

- Nike Risk EverythingDocumento17 páginasNike Risk EverythingTatyana MaayahAinda não há avaliações