Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Obgyn PDF

Enviado por

Sandhya Putri ArisantiDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Obgyn PDF

Enviado por

Sandhya Putri ArisantiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

L**e_SS,h#.0t-osgZ.xX:F?'b4!I{rio+>wh1tE|;_;PfeP<.

s0,'-

<m:e.0'rX,AwS+"-JG4t-rsit,{;3Ss*eb==S.>jEEM3.t_sw*<_i-;';ris:w,S.Z1

_@.:w,"o$*-C.AN};

gi,.:rkE70rtsf.!,-'S^ c.',

..

+ l:

Tract Infection during

Pregnancy: Its Association with

Maternal Morbidity and Perinatal

Outcome

Urinary

t^7S-e; "

it

:.

.t.:

s:

.S ;f,

2{

-;

'S M is ,- p

.i.-l . s

,:#

.^^,

;,t';.

;4t,Qj.

..............

..

',}

4, X

B t>R.iF'-+.'S

bR" ..

';

....

> -; +.

<- -! >-- et s

fU;

.;

;j_t4b

e;3tg'

!.!6

*ilgg-'4

'>;ffiffi

i2x?;Q

*.,

-sz,.g

...

* { X tS

s z__d.s .

*; :,; 4=s..i e*. .:.

v

2' ;'Sx {s v*'s i

*;

--

..

,w, ?..

.$*

':

-. .> -

t S;, s 8

.4 s e-

..

...

t ,,';

-sS

:.

;'

S\^,7el;

;'

"

^ "

''

.t

..

Introduction

Despite a plethora of research since

Kass first noted an association between

untreated urinary tract infection and

perinatal mortality in 1962,1 the extent

to which antepartum urinary tract infection affects maternal and perinatal health

remains ambiguous. At present, the only

certain conclusion is that the risk of

progression to pyelonephritis greatly

increases during pregnancy, with rates as

high as 30% reported among untreated

women.1-7

*ito

fi;hD .\-

t.

->'.

.24

*E

*|

Laura A. Schieve, MS, Arden Handler, DrPH, Ronald Hershow, MD,

Victoria Persky, MD, and Faith Davis, PhD

::

Antepartum urinary tract infection

has also been implicated as a risk factor

for adverse perinatal outcomes-premature birth and/or low birthweightl,3-5'7-14

and perinatal deathl"4'9-in numerous

observational studies. However, an equal

number of negative findings have been

reported.2'6"15-28 Results of clinical trials

examining the effect of antibiotic treatment on reducing the risk of low

birthweight have been inconsistent as

well.1'3'4'7'9'10 In addition, associations

have been documented between antepartum urinary tract infection and a variety

of maternal complications of pregnancy,

including hypertension/preeclampsia,4'5,7,8"17

anemia,8'9"15'22 amnionitis,21 and endometritis.29 The causal nature of these

associations is questionable, because it is

not always clear whether an episode of

urinary tract infection preceded the

particular outcome of interest, especially

in regard to maternal hypertension and

anemia. Although the definitions of

these outcomes in many studies render it

difficult to determine the proper sequence of events, a temporal relationship between urinary tract infection and

hypertension was clearly established by

Stuart et al.,5 and a temporal relationship between urinary tract infection and

anemia was established by Brumfitt.9

These results support possible causal

relationships. As with the perinatal

outcomes, many investigators have also

failed to demonstrate any effect with

urinary tract infection and maternal

outcomes.2'6'11'16'20,2427 Limited sample

sizes and inadequate control of confounders may partially explain the discrepancy in findings to date.

This study used registry data to

examine associations between antepartum urinary tract infection and adverse

maternal and perinatal outcomes independent of other possible risk factors.

The large sample size afforded by the

registry also provided an opportunity to

evaluate possible mechanisms through

which urinary tract infection might exert

an effect on pregnancy outcome.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis with data from the University of Illinois Perinatal Network database, a registry of more than 150 000

obstetric events occurring from 1983

through 1989 in 14 hospitals in the

Chicago area. Trained personnel abstracted more than 450 maternal, fetal,

and neonatal variables from patients'

medical records upon completion of

pregnancy. We limited our analysis to

1988 and 1989 because of changes in

abstracting format. We also limited the

analysis to the four hospitals with the

The authors are with the School of Public

Health, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Requests for reprints should be sent to

Laura A. Schieve, MS, Program in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health,

University of Illinois at Chicago, PO Box

6998, Chicago, IL 60680.

This paper was accepted June 2, 1993.

ft

Ji i*4'8d'Sj Nb sr

b s

American Journal of Public Health 405

Schieve et al.

largest obstetric populations to allow a

feasible reabstraction of a subset of

records, in order to assess the exposure

classification more thoroughly. All singleton live births and fetal deaths were

included, with the exception of 115

subjects for whom information on urinary tract infection was not recorded

(0.4% of the sample). In all, 25 746

women were included in this analysis;

1988 (7.7%) were considered positive for

antepartum urinary tract infection and

constituted the exposure group. The

remainder constituted the nonexposed

group.

Classification of urinary tract infection was based on (1) a positive urine

culture during the antepartum period, as

noted by a health care provider and

recorded in the medical record, or (2) a

diagnosis of urinary tract infection and/or

pyelonephritis during the antepartum

period recorded in the medical record.

This allowed inclusion of cases of urinary tract infection diagnosed by a

variety of methods, including culture,

rapid-screening techniques, and clinical

presentation. In most cases, it was not

possible to discern the way in which a

diagnosis was made from the information provided in the record. Our definition of urinary tract infection encompassed both asymptomatic and

symptomatic infections because it included those individuals for whom a

positive culture was recorded without a

stated diagnosis of urinary tract infection. However, we were unable to determine the proportion of our exposed

group that was symptomatic from the

information provided.

The perinatal outcomes examined

in this study include perinatal death

(fetal death or neonatal death within the

first 28 days of life, providing that the

infant had not been discharged from the

hospital), low birthweight (2500 g or

lower) prematurity (less than 37 weeks

gestation), preterm low birthweight (2500

g or lower and less than 37 weeks

gestation), and small for gestational age

(birthweight less than the 10th percentile of the birthweight distribution of the

singleton deliveries in the database at

each gestational age and infant sex).

Maternal outcomes evaluated include premature labor (onset of labor

prior to 37 weeks of gestation, even if the

episode was resolved and the pregnancy

went to term), hypertension/preeclampsia (diagnosis of pregnancy-induced hypertension or preeclampsia specified by

a health care provider), anemia (hemato406 American Journal of Public Health

crit less than 30%), amnionitis (diagnosis of amnionitis, chorioamnionitis, membranitis, or placentitis), and endometritis

(diagnosis of endometritis or endomyometritis). Because the exact timing of

maternal complications was not recorded for this data set, it is unknown

whether an episode of urinary tract

infection actually preceded each of these

outcomes. Therefore, this study is actually cross-sectional with respect to the

maternal outcomes.

Because sexual intercourse is a risk

factor for both urinary tract and genital

tract infections and since genital tract

infections may also be associated with

adverse reproductive outcome, the detection of one or more genital tract pathogens during the antepartum period

(syphilis, gonorrhea, genital herpes, condyloma, chlamydia, Beta Streptococcus

vaginal infection, Candida albicans,

Trichomonas vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, unspecified vaginitis or cervicitis)

was treated as a potential confounder in

this analysis. Since ascertainment of

antepartum urinary tract infection may

have varied by hospital, odds ratios were

also adjusted for hospital of delivery.

Other variables evaluated as potential

confounders include age ( < 20, 20

through 29, 2 30 years), race/ethnicity

(White/Asian/other, Black, Hispanic),

and prior pregnancy history. Pregnancy

history was classified as follows: (1)

primigravida, (2) at least one pregnancy

ending in adverse outcome (congenital

anomaly; fetal, neonatal, or postneonatal death; ectopic pregnancy or hydatid

mole; spontaneous abortion; premature

birth; or term birth with intrauterine

growth retardation), (3) at least one

pregnancy ending in induced abortion

and no others ending in adverse outcomes or (4) all pregnancies ending in

healthy outcomes (term births with no

congenital anomalies or growth retardation).

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% testbased confidence intervals (CIs) were

computed for exposure to antepartum

urinary tract infection and all perinatal

and maternal outcomes. Mantel-Haenszel adjusted odds ratios were estimated

from stratified analyses of all associations controlling for each of the potential confounders individually.30 These

summary estimates were evaluated with

Breslow-Day tests of homogeneity.

Unconditional logistic regression

was used to simultaneously adjust for

age, race, prior pregnancy history, hospital of delivery (A, B, C, or D), and

antepartum genital tract infection for

each outcome. In addition, because

univariate analysis revealed that the risk

estimate for urinary tract infection and

perinatal death was not homogeneous

with respect to age, urinary tract infection and age interaction terms were

entered into the model with perinatal

death. Odds ratios were calculated from

beta coefficients, and 95% confidence

intervals were calculated from the respective standard errors.31

Because any association between

urinary tract infection and adverse reproductive outcome may vary by the severity

of infection, we repeated our analysis

after subdividing the exposure group by

progression to pyelonephritis. This analysis is presented only for the perinatal

outcomes, however, since the number of

subjects with both pyelonephritis and

one of the maternal outcomes under

study was very small and odds ratios

were difficult to interpret. The relationship between the timing of infection and

each outcome variable would also be of

interest. Unfortunately, the data to

address this issue were not available.

We also explored possible mechanisms by which urinary tract infection

might affect perinatal outcome. Hypertension, anemia, and amnionitis were

evaluated as possible intermediaries in

the association between urinary tract

infection and adverse perinatal outcome, because each of these conditions

has been previously implicated as a

consequence of antepartum urinary tract

infection4,5'7-9'15'17'21'= and a risk factor

for adverse perinatal outcome.32-35 These

analyses were limited to preterm low

birthweight, the outcome with which

urinary tract infection appeared most

strongly associated, because any effect

would be most likely with this association. We repeated both crude and

multivariable analyses, excluding subjects with each of the postulated intermediary variables to assess whether the

associations persisted in their absence.

Finally, in an effort to discern

whether urinary tract infection per se is

a risk factor for preterm low birthweight

or whether the infectious process in

general creates risk, the effect of urinary

tract infection was compared with other

infections commonly acquired by women

of childbearing age, specifically genital

and upper respiratory tract infections.

The study population was divided into

five mutually exclusive exposure groups:

urinary tract infection only, genital tract

infection only, upper respiratory tract

March 1994, Vol. 84, No. 3

Urinary Tract Infections

infection only, multiple infections (more

than one of these three infections), and

none of these infections. Odds ratios

were calculated for each exposure group

and preterm low birthweight, with the no

infection group as the reference category.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the exposure

groups were not homogeneous with

respect to the potential confounding

variables under study. Subjects classified

in the urinary tract infection category

were more likely than those in the

nonexposed group to be non-White, to

be younger, to have delivered at hospital

D, and to have had an antepartum

genital tract infection. They were less

likely to have had a prior pregnancy that

ended in a healthy outcome.

Women exposed to antepartum urinary tract infection were found to be at

greater risk (unadjusted) of delivering

infants with low birthweights, premature

infants, preterm infants with low birthweights, and infants small for gestational

age than those who were not exposed

(Table 2). They were also more likely to

experience premature labor, hypertension/preeclampsia, anemia, and amnionitis during pregnancy. Although the

perinatal mortality and endometritis

rates were higher among the exposure

group, these differences did not reach

statistical significance.

The risk of urinary tract infection

on adverse perinatal outcomes was greatest among those with the most severe

infection, pyelonephritis (Table 3). However, because only a small percentage of

subjects (8.1%) progressed to pyelonephritis, the odds ratios after excluding

these subjects from the exposure group

were virtually the same as when exposure was defined as both pyelonephritis

and nonpyelonephritis cases of urinary

tract infection combined.

After single-factor adjustment for

age, race, hospital of delivery, prior

pregnancy history, and genital tract

infections, all statistically significant associations in the crude analysis, with the

exception of the urinary tract infectionsmall for gestational age association,

remained elevated (data not shown). A

significant association was also found

between urinary tract infection and

perinatal death when maternal age was

between 20 and 29 years.

Multivariable adjustment reduced

the risk estimates, but the associations

March 1994, Vol. 84, No. 3

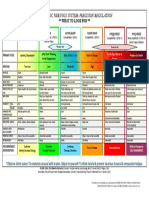

TABLE 1 Selected Characteristics of Study Subjects, by Exposure to

Antepartum Urinary Tract Infection

Characteristic

Race*

White/Asian/other

Black

Hispanic

Age*

<20

20-29

30+

Hospital of delivery*

A

B

C

D

Prior pregnancy history*

Primigravida

Previous adverse outcome

Induced abortion (no adverse outcome)

All healthy outcomes

Genital tract infection*

Exposed

(n = 1988), %

Nonexposed

(n = 23 758), %

28.7

30.1

41.1

47.0

17.8

35.3

22.6

57.5

19.9

13.9

54.5

31.6

17.5

28.9

15.3

38.3

36.6

25.5

15.9

22.1

30.7

27.4

11.9

30.0

21.2

29.4

24.0

10.0

36.7

11.3

*P < .001 by chi-square test for proportional differences for comparison between exposure groups.

between antepartum urinary tract infection and low birthweight, prematurity,

preterm low birthweight, premature labor, hypertension, anemia, and amnionitis remained statistically significant

(Table 4). As in the univariate analysis,

the small for gestational age adjusted

odds ratio was not significant, and the

adjusted odds ratio for perinatal death

was significant only for those 20 to 29

years old.

Neither the crude nor the adjusted

odds ratio was modified when hypertension, anemia, or amnionitis cases were

deleted from the urinary tract infectionpreterm low birthweight analyses (adjusted OR excluding hypertension = 1.4,

95% CI = 1.2, 1.7; adjusted OR excluding anemia = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.2, 1.8;

adjusted OR excluding amnionitis = 1.4,

95% CI = 1.1, 1.7). The risk of preterm

low birthweight was virtually the same

for women with an antepartum urinary

tract infection only, an antepartum genital tract infection only, or both types of

infection (Table 5). (Because of the

unstable estimates from the multivariable analyses, only the unadjusted estimates are presented.) Women exposed

to upper respiratory tract infection only

were at no greater risk of delivering

preterm low-birthweight infants than

were those in the "infection-free" group.

Discussion

We found that women who acquire

urinary tract infections during pregnancy are at increased risk of delivering

low-birthweight, premature, and preterm low-birthweight infants. Our odds

ratios of 1.4 for low birthweight, 1.3 for

prematurity, and 1.5 for preterm low

birthweight compare well with a recent

meta-analysis of exposure to antepartum

urinary tract infection that reported

typical relative risks of 1.5 and 2.0 for

associations with low birthweight and

prematurity, respectively.36 Antepartum

urinary tract infection was not associated with delivering infants small for

gestational age after multivariable adjustment for potential confounding variables, suggesting that urinary tract infection affects low birthweight through

premature delivery rather than growth

retardation. This is further illustrated by

the relatively strong association between

urinary tract infection and premature

labor. Antepartum urinary tract infection was also found to be associated with

increased maternal morbidity (hypertension, anemia, and amnionitis).

An association between urinary tract

infection and perinatal death was found

only among the 20- to 29-year-olds. One

plausible explanation is that younger

American Journal of Public Health 407

Schieve et al.

TABLE 2-Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Exposure to Antepartum Urinary Tract

Infection and Selected Perinatal and Maternal Outcomes

Odds

Outcome

Nonexposed

Exposed

Ratio

95% Confidence

Interval

Perinatal

Perinatal death

Yes

No

Birthweight, g

<2500

>2500

Gestational age, wk

<37

.37

Preterm low birthweight

Yes

No

Small for gestational age

Yes

No

32

1 956

291

23467

13

1.3

09,9

225

1 759

1 779

21 942

16

1.4,1.8

293

1 687

2 546

21 137

1.4

1.3,1.6

155

1 821

1 144

22 505

1.7

1.4, 2.0

258

1 717

2 529

21 108

13

1

1.1

1,.1.4

0.9,1.9

Maternal

Premature labor

Yes

No

Hypertension

Yes

No

Anemia

Yes

No

Amnionitis

Yes

No

Endometritis

Yes

No

2211

21 547

1.8

1.6, 2.0

1 679

122

973

22 785

1.5

1.3,1.9

1 862

123

716

23 042

2.1

1.8, 2.6

1 861

54

1 929

413

234311

1612

306

25

203

1 957

23 525

1.6

1.2,2.1

1.5

1.0, 2.2

Note. Subjects missing information on an outcome variable are not included in that analysis. The

maximum number missing is 134 (small for gestational age).

TABLE 3-Association between Antepartum Urinary Tract Infection and Selected

Perinatal Outcomes, by Progression to Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis

Nonpyelonephritis

Odds

Ratio

95% Confidence

Interval

Odds

Radio

95% Confidence

Outcome

Perinatal death

Low birthweight

Prematurity

Preterm low birthweight

Small for gestational age

2.6

1.9

1.9

2.5

1.5

1.1, 6.2

1.2, 2.9

1.3, 2.9

1.6, 4.0

1.0,2.3

1.2

1.5

1.4

1.6

1.2

0.8,1.8

1.3,1.8

1.2,1.6

1.3,1.9

1.1,1.4

and older women are exposed to mul-

tiple competing risks for adverse outcomes-low socioeconomic status and

related factors among the younger age

group and biological factors among the

408 American Journal of Public Health

Interval

older age group-which masks the impact of urinary tract infection.37

While several previous investigations have found comparable results,

they have suffered from small sample

sizes and were not adequately able to

control for confounding. Of particular

interest is whether the effects of urinary

tract infection are independent of other

infections with similar risk factors for

acquisition, such as sexually transmitted

diseases. We were able to adjust for

antepartum sexually transmitted diseases and other genital tract pathogens

in our analysis and did not find any

change in the odds ratios. In addition,

urinary tract infection and genital tract

infection appear to have had similar

effects on preterm low birthweight, as

evidenced by the comparable odds ratios, when each type of infection was

evaluated individually. However, we did

not distinguish the genital infection

category by specific pathogens. Our

analysis also shows that the associations

observed between urinary tract infection

and both adverse perinatal outcome and

maternal morbidity were not due to

confounding by age, race, prior pregnancy history, or hospital of delivery.

A major weakness of this study is

the method of exposure ascertainment.

While most prior investigations have

been conducted prospectively, with urine

cultures on all women under investigation available to classify urinary tract

infection, this study relied on a positive

culture result or physician diagnosis of

urinary tract infection and/or pyelonephritis in the medical record. This

retrospective classification of urinary

tract infection raised a number of concerns about the validity and reliability of

this variable. Although it was impossible

for us to assess validity directly, we

reabstracted a random sample of charts

from our study population to evaluate

the reliability of the original abstraction

process and to provide some sense of

potential limitations of the urinary tract

infection variable beyond abstraction

error. In all, 217 charts were reabstracted, 112 from the exposed group

(5%) and 105 from the nonexposed

group (0.4%).

Agreement between this second

abstraction and the original classification of urinary tract infection in the

database was 96.2% for the nonexposed

group but only 69.6% for the exposure

group. (That is, 30.4% of our exposure

group was not reclassified as having a

urinary tract infection, during the second abstraction.) Further evaluation of

these apparently misclassified subjects

revealed that the incidence of adverse

outcomes was lower in this group than

for those classified correctly as having a

March 1994, Vol. 84, No. 3

Urinary Tract Infections

TABLE 4-Adjusted Odds Ratios

for Exposure to Antepartum Urinary Tract

Infection and Selected

Perinatal and Maternal

Outcomes

Outcome

Odds

Ratio

Perinatal

Perinatal death

0.3

Age<20d

1.8

Age2G-29d

1.1

Age30+d

1.4

Low birthweight

1.3

Prematurity

Pretermlowbirth- 1.5

weight

1.1

Small for gestational age

Maternal

Premature labor 1.6

1.4

Hypertension

1.6

Anemia

1.4

Amnionitis

1.0

Endometritis

95% Confidence

Interval

0.1,1.3

1.1,2.8

0.5,2.3

1.2,1.6

1.1,1.4

1.2,11.7

0.9,1.3

1.4,1.8

1.2,1.7

1.3, 2.0

1.1, 1.9

0.6,1.5

Note. Estimates were adjusted for race,

age, prior pregnancy history, hospital of

delivery, and genital tract pathogens by

means of unconditional logistic regression. Subjects missing information on

outcome or confounding variables are

not included in that analysis. The maximum number missing is 357 (small for

gestational age). Stratum-specffic estimates were adjusted for race, prior

pregnancy history, hospital of delivery,

and genital tract pathogens.

urinary tract infection. Therefore, including these subjects in the exposure group

biased our results toward the null hypothesis, and the true associations are likely

to be stronger than our estimates indicate.

In addition to abstraction quality,

the classification of urinary tract infection used in this study is subject to a

number of other potential shortcomings.

First, if a woman did not receive

prenatal care, an episode of urinary tract

infection may have occurred during

pregnancy that went unrecorded. In

addition, even if a woman did receive

prenatal care, her prenatal care record

may not have been incorporated into her

hospital of delivery medical record,

potentially resulting in a missed case of

urinary tract infection. Our reabstraction revealed that 13.4% of our study

population did not receive prenatal care

and that the prenatal care record was

unavailable for an additional 4.8%.

March 1994, Vol. 84, No. 3

TABLE 5-Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Exposure to Antepartum Urinary Tract

Infection (UTI), Genital Tract Infection, Upper Respiratory Tract

Infection (URI), and Combinations of These Infections for

Preterm Low Birthweight

Exposure

Odds Ratio

95% Confidence Interval

Negative for all 3 infections

UTI only

Genital infection only

URI only

Multiple infections

UTI and URI

UTI and genital infection

URI and genital infection

All 3 infections

19 927

1 464

2 475

1 053

706

94

394

194

24

1.0

1.8

1.5

0.8

1.6

1.4

1.9

1.2

0.9

1.4, 2.1

1.3,1.8

0.6,1.2

1.2, 2.2

0.6, 3.3

1.3, 2.7

0.6, 2.3

0.1, 6.1

In addition to receipt of prenatal

care, we were also concerned about the

prevalence of laboratory screening for

urinary tract infection. Although most

prenatal care regimes include an antepartum urinalysis, not all routinely incorporate urine cultures. We found that

antepartum urine cultures were recorded for only 33.2% of our reabstracted sample. This is most likely an

underestimate, because it is feasible that

urine cultures performed during the

antepartum period were not always

recorded in the medical record. However, it is still cause for concern, since

urinary tract infection may be asymptomatic and urinalysis alone may be insensitive. Although these data suggest that

cases of asymptomatic urinary tract

infection may have gone undetected in

this population, any consequent bias

would again be toward the null hypothesis because comparison groups would

be more homogeneous on exposure.

Given the potential errors in classification, it is encouraging to note that the

prevalence of urinary tract infection at

each hospital under study fell within the

2% to 10% range seen in other investigations.1,3,5,6,12,15,26 This rate was actually

exceeded at one hospital that serves a

large number of indigent women, an

observation also consistent with current

literature.

Although the registry does not

contain information on antibiotic treatment for urinary tract infection, we

found, during our reabstraction, that

antibiotics were prescribed for 84.6% of

those correctly classified as having such

an infection, indicating that the exposure group involves mainly treated cases.

Assuming that the association between urinary tract infection and prematurity is real, the mechanism by which

the former might exert such an effect is

not well established. Several investigators have demonstrated a high incidence

(up to 50%) of pyelographic abnormalities, indicative of chronic pyelonephritis,

in bacteriuric women.4'38 It is plausible,

then, that the effect of urinary tract

infection on premature birth could be

indirectly mediated by occult renal abnormalities that result in antepartum maternal complications such as hypertension/

preeclampsia or anemia. Our data do

not support this hypothesis, because no

change in the odds ratio was observed

for the association between urinary tract

infection and preterm low birthweight

when women with either hypertension or

anemia were excluded from analysis. We

cannot eliminate other possible effects

of renal abnormalities, however.

It is also conceivable that urinary

tract infection affects premature labor

directly, through the development of

amnionitis. It has been previously suggested that bacterial infection of the

amniotic fluid is a risk factor for premature delivery.3435 One hypothesis contends that bacterial enzymes such as

collagenase may weaken the fetal membranes and predispose them to rupture,

which subsequently triggers the onset of

labor.39 It has also been postulated that

bacterial products such as phospholipase

A and C or endotoxins may stimulate

prostaglandin biosynthesis by the fetal

membranes, which then initiates labor.40

Alternatively, these bacterial products

might stimulate the patient's immune

system, causing the release of monokines

(particularly Platelet Activating Factor,

Interleukin-1, and Tumor Necrosis Factor) that then trigger prostaglandin

production.40 It has also been demonstrated that bacteriuric women may

subsequently develop an amniotic fluid

American Journal of Public Health 409

Schieve et al.

infection with the same organisms commonly isolated from urine specimens,

namely coliform bacteria such as Escherichia coli. 21 We found no change in the

odds ratio after deleting cases of amnionitis, although subclinical amniotic infection has been repeatedly documented4143

and may have been a latent causative

factor in this population.

Future studies are needed to address the interrelationship between urinary tract infection, amnionitis, and

premature labor. Ideally, these associations should be explored in a prospective

study with well-defined criteria for both

exposure and outcome variables.

Although the mechanism remains

unclear, these data, along with prior

investigations, indicate that antepartum

urinary tract infection indeed affects

both maternal and perinatal health, even

when treated. Early prenatal screening

of women for urinary tract infection and

treatment of women found to be bacteriuric are already indicated to prevent

progression to pyelonephritis. The associations documented here provide further compelling support for screening to

identify patients at risk for adverse

pregnancy outcomes. [

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the University of Illinois

Perinatal Management Group for allowing us

access to the database. In addition, we would

like to thank Deborah Rosenberg and Cynthia Ferre for their assistance with computer

programming and Susan Ataman, Susan

Johnson, and Edna Brooks for their help with

data collection.

References

1. Kass EH. Pyelonephritis and bacteriuria:

a major problem in preventive medicine.

Ann Intem Med. 1962;56:46-53.

2. Bryant RE, Windom RE, Vineyard JP,

Sanford JP. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in

pregnancy and its association with prematurity. JLab Clin Med. 1964;63:224-231.

3. LeBlanc AL, McGanity WJ. The impact

of bacteriuria in pregnancy-a survey of

1300 pregnant patients. Biol Med. 1964;22:

336-347.

4. Kincaid-Smith P, Bullen M. Bacteriuria

in pregnancy. Lancet. 1965;1:395-399.

5. Stuart KL, Cummins GTM, Chin WA.

Bacteriuria, prematurity, and the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Br Med J.

1965;1:554-556.

6. Little PJ. The incidence of urinary infection in 5000 pregnant women. Lancet.

1966;4:925-928.

410 American Journal of Public Health

7. Wren BG. Subclinical urinary infection in

pregnancy. Med JAust. 1969;1:1220-1226.

8. Naeye RL. Urinary tract infections and

the outcome of pregnancy. Adv Nephrol.

1986;15:95-102.

9. Brumfitt W. The effects of bacteriuria in

pregnancy on maternal and fetal health.

KidneyInt. 1975;8:S113-S119.

10. Savage WE, Haj SN, Kass EH. Demographic and prognostic characteristics of

bacteriuria in pregnancy. Medicine. 1967;

46:385-407.

11. Condie AP, Williams JD, Reeves DS,

Brumfitt W. Complications of bacteriuria

in pregnancy. In: O'Grady F, Brumfitt W,

eds. Urinary Tract Infection. London,

England: Oxford University Press; 1968:

148-159.

12. Gruneberg RN, Leigh DA, Brumfitt W.

Relationship of bacteriuria in pregnancy

to acute pyelonephritis, prematurity, and

fetal mortality. Lancet. 1969;2:1-3.

13. McGrady GA, Daling JR, Peterson DR.

Maternal urinary tract infection and

adverse fetal outcomes. Am J Epidemiol.

1985;121:377-381.

14. Henderson M, Reinke WA. The relationship between bacteriuria and prematurity. In: Kass EH, ed. Progress in Pyelonephritis. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis; 1965:

27-32.

15. Layton R. Infection of the urinary tract in

pregnancy: an investigation of a new

routine in antenatal care. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonwealth. 1964;71:927-933.

16. Sleigh JD, Robertson JG, Isdale MH.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. J

Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonwealth. 1964;

71:74-81.

17. Norden CW, Kilpatrick WH. Bacteriuria

of pregnancy. In: Kass EH, ed. Progress in

Pyelonephritis. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis;

1965:64-72.

18. Whalley PJ. Bacteriuria in pregnancy. In:

Kass EH, ed. Progress in Pyelonephritis.

Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis; 1965:50-57.

19. Wilson MG, Hewitt WL, Monzon OT.

Effect of bacteriuria on the fetus. NEnglJ

Med. 1966;274:1115-1118.

20. Dixon HG, Brant HA. The significance of

bacteriuria in pregnancy. Lancet. 1967;1:

19-20.

21. Patrick MJ. Influence of maternal renal

infection on the foetus and infant. Arch

Dis Child. 1967;42:208-213.

22. Robertson JG, Livingstone JRB, Isdale

MH. The management and complications

of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonwealth. 1968;75:59-65.

23. Elder HA, Santamarina BAG, Smith S,

Kass EH. The natural history of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy: the

effect of tetracycline on the clinical

course and the outcome of pregnancy.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;111:441-462.

24. Schamadan WE. Bacteriuria during pregnancy. Am J Obstet GynecoL 1964;89:1015.

25. Carroll R, MacDonald D, Stanley JC.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

Bacteriuria in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol.

1968;32:525-527.

Bobeck S, Schersten B. Detection and

diagnosis of bacteriuria in pregnancy.

Practitioner. 1974;212:257-262.

Gilstrap LC, Leveno KJ, Cunningham

FG, Whalley PJ, Roark ML. Renal

infection and pregnancy outcome. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141:709-716.

Reddy J, Cambell A. Bacteriuria in

pregnancy. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol.

1985;25:176-178.

Monif GRG. Intrapartum bacteriuria and

postpartum endometritis. Obstet Gynecol.

1991;78:245-248.

Rothman KJ. Modem Epidemiology. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown; 1986:177-236.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York, NY: Wiley;

1989:38-81.

Kramer MS, McLean FH, Eason EL,

Usher RH. Maternal nutrition and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol.

1992;136:574-583.

Lieberman E, Ryan KJ, Monson RR,

Schoenbaum SC. Association of maternal

hematocrit with premature labor. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:107-114.

Chellam VG, Rushton DI. Chorioamnionitis and funiculitis in the placentas of 200

births weighing less than 2.5 kg. Br J

Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:808-814.

Guzick DS, Winn K. The association of

chorioamnionitis with preterm delivery.

Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:11-16.

Romero R, Oyarzun E, Mazor M, Sirtori

M, Hobbins JC, Bracken M. Metaanalysis of the relationship between

asymptomatic bacteriuria and preterm

delivery/low birth weight. Obstet Gynecol.

1989;73:576-582.

37. Institute of Medicine. Preventing Low

Birthweight. Washington, DC: National

Academy Press; 1985:46-93.

38. Diokno AC, Compton A, Seski J, Vinson

R. Urologic evaluation of urinary tract

infection in pregnancy. J Reprod Med.

1986;31:23-26.

39. Cox SM. Infection-induced preterm labor. In: Gilstrap LC, Faro S, eds. Infections in Pregnancy. New York, NY: Alan

R Liss Inc; 1990:247-253.

40. Romero R, Mazor M. Infection and

preterm labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1988;

31:553-584.

41. Miller JM, Hill GB, Welt SI, Pupkin MJ.

Bacterial colonization of amniotic fluid in

the presence of ruptured membranes.

Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:451-458.

42. Bobitt JR, Hayslip CC, Damato JD.

Amniotic fluid infection as determined by

transabdominal amniocentesis in patients

with intact membranes in premature

labor.AmJObstet Gynecol. 1981;140:947952.

43. Leigh J, Garite TJ. Amniocentesis and

the management of premature labor.

Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:500-506.

March 1994, Vol. 84, No. 3

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Sandhya 1Documento8 páginasSandhya 1Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Acs - Sept.12Documento72 páginasAcs - Sept.12Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Sandhya 4Documento7 páginasSandhya 4Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- AnkleDocumento9 páginasAnkleSwan YeongAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Sandhya 4Documento7 páginasSandhya 4Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Sandhya 5Documento4 páginasSandhya 5Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Jurnal Vertigo Sandhya PDFDocumento8 páginasJurnal Vertigo Sandhya PDFSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocumento16 páginasRespiratory Distress SyndromeSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Sandhya 1Documento8 páginasSandhya 1Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocumento16 páginasRespiratory Distress SyndromeSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Acs - Sept.12Documento72 páginasAcs - Sept.12Sandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Jurnal Mata Sandhya PDFDocumento8 páginasJurnal Mata Sandhya PDFSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- BPT - Free MedicalDocumento8 páginasBPT - Free MedicalSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- ObatantihipertensiDocumento15 páginasObatantihipertensiSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Jurnal Vertigo PDFDocumento5 páginasJurnal Vertigo PDFSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Jurnal Mata Sandhya PDFDocumento8 páginasJurnal Mata Sandhya PDFSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocumento16 páginasRespiratory Distress SyndromeSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- 1471 2415 14 151 PDFDocumento7 páginas1471 2415 14 151 PDFSandhya Putri ArisantiAinda não há avaliações

- UltraCal XS PDFDocumento2 páginasUltraCal XS PDFKarina OjedaAinda não há avaliações

- Sistema NervosoDocumento1 páginaSistema NervosoPerisson Dantas100% (2)

- Kera Ritual Menu - With DensifiqueDocumento8 páginasKera Ritual Menu - With Densifiquee.K.e.kAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Peplu Theory ApplicationDocumento7 páginasPeplu Theory ApplicationVarsha Gurung100% (1)

- REACH - Substances of Very High ConcernDocumento3 páginasREACH - Substances of Very High Concerna userAinda não há avaliações

- Maria MontessoriDocumento2 páginasMaria MontessoriGiulia SpadariAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Purpose 1Documento4 páginasPurpose 1Rizzah MagnoAinda não há avaliações

- Tiger Paint Remover SDSDocumento10 páginasTiger Paint Remover SDSBernard YongAinda não há avaliações

- Report Decentralised Planning Kerala 2009 OommenDocumento296 páginasReport Decentralised Planning Kerala 2009 OommenVaishnavi JayakumarAinda não há avaliações

- Lab Exercise 11 Urine Specimen CollectionDocumento7 páginasLab Exercise 11 Urine Specimen CollectionArianne Jans MunarAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Transformer Oil BSI: Safety Data SheetDocumento7 páginasTransformer Oil BSI: Safety Data Sheetgeoff collinsAinda não há avaliações

- AnumwraDocumento30 páginasAnumwratejasAinda não há avaliações

- L 65 - Prevention of Fire and Explosion, and Emergency Response On Offshore Installations - Approved Code of Practice and Guidance - HSE - 2010Documento56 páginasL 65 - Prevention of Fire and Explosion, and Emergency Response On Offshore Installations - Approved Code of Practice and Guidance - HSE - 2010Barkat UllahAinda não há avaliações

- 11 - Chapter 3Documento52 páginas11 - Chapter 3joshniAinda não há avaliações

- CelecoxibDocumento2 páginasCelecoxibXtinegoAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation 1Documento18 páginasCase Presentation 1api-390677852Ainda não há avaliações

- Forging An International MentorshipDocumento3 páginasForging An International MentorshipAbu SumayyahAinda não há avaliações

- MIP17 - HSE - PP - 001 Environment Management Plan (EMP) 2021 REV 3Documento40 páginasMIP17 - HSE - PP - 001 Environment Management Plan (EMP) 2021 REV 3AmeerHamzaWarraichAinda não há avaliações

- CCAC MSW City Action Plan Cebu City, PhilippinesDocumento6 páginasCCAC MSW City Action Plan Cebu City, Philippinesca1Ainda não há avaliações

- Economics Assignment (AP)Documento20 páginasEconomics Assignment (AP)Hemanth YenniAinda não há avaliações

- NitrotolueneDocumento3 páginasNitrotolueneeriveraruizAinda não há avaliações

- A Seminar Report On Pharmacy ServicesDocumento20 páginasA Seminar Report On Pharmacy Servicesrimjhim chauhanAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Mohamed Ali Hamedh - DKA - 2023Documento25 páginasDr. Mohamed Ali Hamedh - DKA - 2023ÁýáFáŕőúgAinda não há avaliações

- Transport OshDocumento260 páginasTransport OshAnlugosiAinda não há avaliações

- Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists (Dexmedetomidine) Pekka Talke MD UCSF Faculty Development Lecture Jan 2004Documento53 páginasAlpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists (Dexmedetomidine) Pekka Talke MD UCSF Faculty Development Lecture Jan 2004Nur NabilahAinda não há avaliações

- 863-5-Hylomar - Univ - MSDS CT1014,3Documento3 páginas863-5-Hylomar - Univ - MSDS CT1014,3SB Corina100% (1)

- ED Produk KF - KF (Nama Apotek)Documento19 páginasED Produk KF - KF (Nama Apotek)Eko FebryandiAinda não há avaliações

- Biological Spill Clean UpDocumento5 páginasBiological Spill Clean UpNAMPEWO ELIZABETHAinda não há avaliações

- An Introduction To PrescribingDocumento12 páginasAn Introduction To PrescribingNelly AlvaradoAinda não há avaliações

- Rizal's Visit To The United States (1888Documento23 páginasRizal's Visit To The United States (1888Dandy Lastimosa Velasquez57% (7)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNo EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (6)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsAinda não há avaliações