Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Fundamental Considerations of The Design and Function of Intranasal Antrostomies

Enviado por

sevattapillaiTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Fundamental Considerations of The Design and Function of Intranasal Antrostomies

Enviado por

sevattapillaiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

646

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 79 November 1986

Fundamental considerations of the design and function

of intranasal antrostomies

Valerie J Lund FRcs Institute of Laryngology and Otology, London WCI

Keywords: antrostomy, intranasal; inferior nasal meatus anatomy

Paper read to

Section of

Laryngology,

3 May 1985.

Awarded Downs

Travelling

Scholarship

for 1985

Summary

The natural history of intranasal antrostomy is

poorly understood despite the popularity of the procedure. Researches have been conducted to examine

this and in particular to establish factors which might

be responsible for closure. A complete appraisal ofthe

anatomy of the inferior meatus has been undertaken

to determine factors which limit the dimensions of an

antrostomy. Retrospective and prospective studies

have been performed on patients undergoing the

operation to assess patency and size. The results of

these studies demonstrate that initial size is important in determining long-term patency in adults, and if

an antrostomy is open at one year it usually remains

open in the long-term unless infection supervenes; in

children, however, antrostomies appear to close more

rapidly.

Introduction

The operation of intranasal antrostomy is becoming

increasingly popular in Great Britain1 but its natural

history remains obscure. To elucidate the rationale

for its performance in modern rhinology, the operation has been examined from a number of aspects.

It is commonly accepted that closure may occur27

but if the antrostomy closes, how does it close, how

quickly does it close, and what measurable factors

are associated with closure? Is it simply a question

of operative technique or does it depend on factors

associated with the patient, such as age, or on

individual variation? The role of the initial size

of the antrostomy particularly requires investigation

as it is regarded by many as the most important

determining factor8.

obtained from coronal CT scans and sagittal skulls.

The maximum distance between the floor ofthe sinus

and the floor of the nose ranged from 5 mm to 16 mm.

Evidently a wide range exists, but this does serve to

demonstrate that there is always a potential sump in

the fully developed adult maxillary sinus.

Examination of super-selective arteriograms have

demonstrated a constant vessel arising from the

lateral sphenopalatine artery and supplying the

lateral wall ofthe nose. It is seen entering the inferior

meatus, running superiorly to inferiorly at between

4 and 5 cm along the bony lateral wall. It then

3.

2

E

1-

Pyriform

fosa

cm Into nose

Figure 1. Height of inferior meatus (range and mean)

Anatomy

To establish the maximum inferior meatal antrostomy which could potentially be fashioned, the

anatomy of the area has been re-evaluated. Using

sagittally sectioned skulls and coronal CT scans,

the dimensions of the inferior meatus have been

established (Figure 1) showing a maximum height of

1.6-2.3 cm (average 1.92 cm) at 1.6 cm along the bony

lateral wall.

The bone constituting the inferior meatal wall has

been examined using coronal sections from midfacial

blocks, and demonstrates a change in thickness and

quality within the meatus. A gradual transformation

occurs from compact to lamellar bone, going from

superior to inferior and anterior to posterior, so that

0141-0768/86/

the

thinnest bone lies in the central superior portion

011646-04/$02.00/0

of

the

meatus (Figure 2).

01986

The height ofthe meatus in these specimens ranges

The Royal

from 6-18 mm with the highest point occurring at the

Society of

Medicine

genu of the inferior turbinate, thus confirming data

Figure 2. Coronal section (8p H&E) from adult midfacial

block

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 79 November 1986

Figure 3. Lateral superselective arteriogram showing artery

to inferior meatus (arrowed)

Figure 4. Left inferior meatus showingpinhole antrostomy

descends below the level of the palate, rising again

very anteriorly on the lateral wall. This may be

distinguished from the leash of vessels supplying the

inferior turbinate, the descending palatine running

more posteriorly and inferiorly, and the septal artery

running down and forwards on the vomer (Figure 3).

Thus the fashioning of the maximum potential

inferior meatal antrostomy is limited by a number

of anatomical factors. Macroscopic examination of

gross dimensions of the meatus demonstrate the

attachment of the inferior turbinate which constitutes the superior limit. Inferiorly the increasing

thickness of bone makes it progressively more difflcult to cut down to the floor of the nose, whilst

discrepancy between the floor of nose and floor of

maxillary sinus results in an inevitable sump even if

the inferior margin is completely removed.

The changes in bone thickness as the anterior end

of the inferior turbinate is approached, and decreasing meatal height, preclude anterior extension and in

part explain why the inferior end ofthe nasolacrimal

duct is rarely damaged. The inferior meatal artery is

a constant feature on the 10 arteriograms examined.

Whilst the existence of the lateral conchal branch of

the lateral sphenopalatine artery is established9 - I ,

the path taken by the inferior meatal vessel has not

been previously demonstrated. This explains why, in

making an antrostomy, no significant bleeding is

encountered until 4-5 cm posteriorly. The surgeon's

desire to avoid damage to the vessel and changes in

bone thickness impose the posterior surgical limit.

Retrospective study

Method

All patients who had had intranasal antrostomies

performed during 1979-1982 were asked to attend

the outpatient department to assess patency and size

of antrostomy. This was done using a 4 mm 0' Hopkins

rod, Olympus camera with inbuilt graticule and

Xenon light source. In addition, direct measurement

of the length was possible using a custom-made

instrument. A total of 108 patients were assessed.

Results

There were 58 men and 50 women, their ages ranging

from 7 to 73 years. On initial attendance an average of

27 months had elapsed since the operation. Of 216

antrostomies performed, 45% were closed and 50%

patent. The average age of those patients in whom

the antrostomy had closed completely was 35 years

compared with 44 years in the group with patent

antrostomies, confirmingthe clinical impression that

antrostomies close more quickly in younger people.

This group included 13 of the 15 patients aged under

16 at the time of operation.

Patency was considered in relation to time elapsed

since operation and remains constant over several

years, implying that closure occurs, if at all, in the

first year; only 2 antrostomies closed during follow

up. The experience of the operator did not improve

the length of patency, with consultants having the

highest percentage closure of 540% compared to 42%

in registrars. As the initial size of the hole .is

unknown, it is difficult to assess the appearances at

follow up, but the degree of patency varied considerably from holes 2.5 x 0.8 cm to pinholes, which are

presumably a good deal smaller than originally made

(Figure 4). The other main problem with this group

is that the exact criteria for the operation are

unknown, though a review of the notes shows that

the majority had longstanding sinus problems which

could be termed 'chronic'.

Prospective study

Method

All patients undergoing intranasal antrostomy had

an accurate assessment of antrostomy size made at

the time of operation and were then followed up at

regular intervals during which closure was carefully

monitored. Factors relevant to closure such as initial

size, operative technique and postoperative care

were evaluated. All patients had proven antral infection which had failed to respond to conservative

medication and usually one or two washouts. So far

65 patients have been operated on.

Results

There were 24 men and 41 women, their ages ranging

from 11 to 73 years (mean 44). The follow up ranged

from 25 to 104 weeks (mean 58) and 65% of patients

were studied for one year or longer. All had had at

least one antral washout and 20 had had inferior

meatal antrostomies performed in the past.

647

648

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 79 November 1986

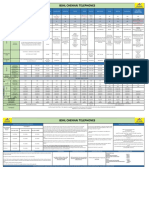

Table 1. Comparison of groups of different sizes by unpaired

t test

Group versus

group (cm)

2.75 x 1 v 2.5 x 1

2.75 x 1 v 2.0 x 1

2.75 x 1 v 1.5 x 1

2.75 x 1 v 1.Ox 1

2.5 xlv2.Oxl

2.5 xlvl.5xl

2.5 xlvl.0x1

2.0 x 1 v 1.5x l

2.0 x 1 v 1.0 x 1

1.5 x 1 v 1.0 x 1

Initial %

closure

-2.880

-2.980

-3.370

-6.480

-0.73

% Closure at

one year

-1.16

-4.990

-0.62

-4.640

-1.62

-1.24

-1.990

-5.370

0.76

0.64

4.520

-1.33

5.170

-3.830

-3.840

Final %

closure

-0.62

-0.44

-1.08

-3.050

0.39

0.70

3.120

-0.92

3.460

-1.51

0 Significant wherep < 0.001

Figure 5. Right inferior meatal antrostomy 6 weeks

postoperatively

Figure 7. Left large inferior meatal antrostomy with polypoid

mucosa extruding

Figure 6. Same antrostomy as shown in Figure 5, but 3 weeks

later after infection, showing contracture of the hole with pus

pouring out

One hundred and one antrostomies of various sizes

fashioned: 11 at 2.75 cm, 21 at 2.5 cm, 32 at

2.0 cm, 10 at 1.5 cm, 22 at 1.0 cm and 5 at 0.5 cm. The

superoinferior height was 1.0 cm in all cases except

for the 0.5 cm group, which were also 0.5 cm in height.

When the results are considered overall, it becomes

apparent that an initial diminution in size occurs

shortly after surgery, though an average of five

weeks elapsed before an accurate measurement was

possible. The range of early lumen diminution was

8-100%, with an average of 27%. Subsequently 73%

remained completely unchanged, 7 having undergone 100% closure by the first outpatient attendance

(Figure 5). Further gradual closure occurred in 17

antrostomies and rapid closure was observed in 10.

Rapid closure was associated with an obvious clinical infection (severe exacerbation of mucopurulent

discharge) in 9 antrostomies (Figure 6) and resulted

in complete closure in 6.

Percentage closure for each group of different

length was considered overall irrespective of follow

were

up and, if available, at one year follow up. The results

for each group were compared, and demonstrate a

significant difference between the 1 cm group and the

2.0, 2.5 and 2.75 cm groups irrespective of time after

operation (Table 1). In those 9 patients (13 antrostomies) with 100% closure during follow up, there

was 1 at 2.0 x 1.0 cm, 1 at 1.5 x 1.0 cm, 6 at 1.0 x 1.0 cm

and 5 at 0.5 x 0.5 cm, which represents 27% of the

1.0 x 1.0 cm group and 100% of the 0.5 x 0.5 cm group.

Three ofthe 1.0 x 1.0 cm patients were under 16 at the

time of operation.

Patency does not, however, guarantee success and

patients may be clinically symptomatic despite large

antrostomies from which pus or polypoid mucosa

may be seen extruding (Figure 7).

Discussion

It has been possible in the prospective study to eliminate a number of variable factors which are intrinsic

to a retrospective study. All the antrostomies were

performed by the same surgeon, employing an identical operative technique, postoperative management

and serial assessment.

The combined results of the retrospective and

prospective studies demonstrate that, as might be

Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 79 November 1986

expected, intranasal antrostomies close more quickly

in children, given the continuing growth in the

medial wall of the maxilla. They also suggest that if

an antrostomy is open at one year, then it usually

remains open in the long-term and that initial size

is important in determining long-term patency in

adults. Clearly an initial healing occurs within the

first few weeks which is of the same order (0.4 cm) in

all cases and is circumferential. The majority then

remain unchanged unless infection supervenes when

rapid closure may be observed. It is difficult to

define the degree of infection which precipitates this

change, as many patients undergo cyclical symptomatic deterioration and improvement without any

alteration in antrostomy appearance, apart from the

presence of mucopurulent discharge draining from

the sinus.

A recent survey by the author8 confirms that the

operation of intranasal antrostomy is done for widely

differing clinical indications, which is reflected in its

popularity, and using a wide variety of techniques,

which may explain the variable results particularly

with regard to long-term patency. It seems likely,

given the anatomical constraints, that a 2.0 x 1.0 cm

or greater hole is rarely achieved.

Is it possible that surgical conservatism has swung

too far, with more and more antrostomies being

performed for chronic conditions characterized by

irreversible mucosal disease? The physiology and

natural history of antrostomies are poorly understood, and whilst particles of ink can be most beautifully demonstrated streaming towards the natural

ostium in normal sinuses12, the situation with

severely damaged mucous membrane and cilia, and

thick tenacious pus, is quite different.

The critical functional size of the antrostomy in

relation to the viscosity of the secretion remains to

be determined. However, if one accepts that size is

important to the success of the operation, then careful attention to technique is required. Nevertheless,

probably the single most important area is careful

patient selection, and the present study suggests that

it is those patients with a relatively short history

of acute recurrent infection who are most likely to

benefit from the operation.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Mr B Kendall for

his assistance with the arteriography, Dr G Lloyd and Dr J

Palfrey for their help with the anatomy, and Professor D F N

Harrison for his invaluable advice and support.

References

1 Lund VJ. Fundamental considerations on the design

and function of intranasal antrostomies. Rhinology

1985;23:231-6

2 Hempstead B. End results for intranasal operation for

maxillary sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol 1939;30:711-15

3 Moore P. Intranasal antrotomy in maxillary sinusitis.

Surg Clin North Am 1939;19:1243-52

4 Hilding AC. Physiologic basis of nasal operations.

California JMed 1950;72:103-7

5 Capps FCW. Observations on the treatment of infections of the maxillary antrum. J Laryngol Otol 1952;

66:199-210

6 Lavelle RJ, Spencer Harrison M. Infection of the maxillary sinus: the case for the middle meatal antrostomy.

Laryngoscope 1971;81:90-106

7 Mann W, Beck C. Inferior meatal antrostomy in

chronic maxillary sinusitis. Arch Otorhinolaryngol

1978;221:289-95

8 Lund VJ. Design and function of intranasal antrostomies. JLaryngol Otol 1986;100:35-9

9 Warwick R, Williams PL eds. Gray's anatomy. 35th ed.

London: Longman, 1973

10 Djindjian J, Merland JJ. Superselective arteriography of

the external carotid artery. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1978

11 Lasjaunias PL. Craniofacial and upper cervical arteries.

Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1982

12 Proetz AW. Essays on the applied physiology of the nose.

St Louis: Annals Publishing Co, 1941

(Accepted 16 April 1986)

649

Você também pode gostar

- Original Article: 360 Degree Subannular Tympanoplasty: A Retrospective StudyDocumento7 páginasOriginal Article: 360 Degree Subannular Tympanoplasty: A Retrospective StudyAkanshaAinda não há avaliações

- Thyroid Isthmusectomy - A Critical AppraisalDocumento4 páginasThyroid Isthmusectomy - A Critical Appraisalentgo8282Ainda não há avaliações

- Clinical Study of Retraction Pockets in Chronic Suppurative Otitis MediaDocumento4 páginasClinical Study of Retraction Pockets in Chronic Suppurative Otitis Mediavivy iskandarAinda não há avaliações

- Recurent EpistaxisDocumento3 páginasRecurent EpistaxisFongmeicha Elizabeth MargarethaAinda não há avaliações

- CT Scan For SinusitisDocumento6 páginasCT Scan For SinusitisYuke PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Oroantral Communications. A Retrospective Analysis: Josué Hernando, Lorena Gallego, Luis Junquera, Pedro VillarrealDocumento5 páginasOroantral Communications. A Retrospective Analysis: Josué Hernando, Lorena Gallego, Luis Junquera, Pedro VillarrealPla ParichartAinda não há avaliações

- Minimally Invasive Transcanal Removal of Attic CholesteatomaDocumento7 páginasMinimally Invasive Transcanal Removal of Attic CholesteatomaAhmed HemdanAinda não há avaliações

- Carcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheDocumento6 páginasCarcinoma Maxillary Sinus : of TheInesAinda não há avaliações

- Malignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyDocumento1 páginaMalignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyCeriaindriasariAinda não há avaliações

- A Huge Epiglottic Cyst Causing Airway Obstruction in An AdultDocumento4 páginasA Huge Epiglottic Cyst Causing Airway Obstruction in An AdultWaleed KerAinda não há avaliações

- Abdalla 2017Documento3 páginasAbdalla 2017dewaprasatyaAinda não há avaliações

- Pterygium After Surgery JDocumento6 páginasPterygium After Surgery JRayhan AlatasAinda não há avaliações

- Kista TiroglosusDocumento2 páginasKista TiroglosusKhairuman FitrahAinda não há avaliações

- Skullbasesurg00008 0039Documento5 páginasSkullbasesurg00008 0039Neetu ChadhaAinda não há avaliações

- A Clinical Study On Oroantral FistulaeDocumento5 páginasA Clinical Study On Oroantral FistulaeAndreHidayatAinda não há avaliações

- An Alternative Alar Cinch Suture PDFDocumento11 páginasAn Alternative Alar Cinch Suture PDFmatias112Ainda não há avaliações

- Artigo 5Documento8 páginasArtigo 5doctorbanAinda não há avaliações

- Complete surgical excision of pre-auricular sinusesDocumento7 páginasComplete surgical excision of pre-auricular sinusesHerryAsu-songkoAinda não há avaliações

- Changing Trends in The Decompression of Tension PneumothoraxDocumento6 páginasChanging Trends in The Decompression of Tension Pneumothoraxnanang hidayatullohAinda não há avaliações

- Total Laryngectomy Techniques and IndicationsDocumento10 páginasTotal Laryngectomy Techniques and IndicationsSanAinda não há avaliações

- Modified Rives StoppaDocumento8 páginasModified Rives StoppaAndrei SinAinda não há avaliações

- Endoscopicmanagement Ofcom&tympanoplastyDocumento9 páginasEndoscopicmanagement Ofcom&tympanoplastyvipinAinda não há avaliações

- OJOLNS-10 - II - Endoscopic Trans PDFDocumento6 páginasOJOLNS-10 - II - Endoscopic Trans PDFDR K C MALLIKAinda não há avaliações

- Ena 1Documento4 páginasEna 1haneefmdfAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of Spinal Anaesthesia On Penile TumescenceDocumento5 páginasThe Effect of Spinal Anaesthesia On Penile TumescenceMaria MiripAinda não há avaliações

- Annrcse01509 0sutureDocumento3 páginasAnnrcse01509 0sutureNichole Audrey SaavedraAinda não há avaliações

- huang1984Documento4 páginashuang1984vinicius.alvarez3Ainda não há avaliações

- Bergstrom 1973 FrenectomyDocumento6 páginasBergstrom 1973 FrenectomyjeremyvoAinda não há avaliações

- Tunica Vaginalis Flap Reinforcement in Staged Hypospadias RepairDocumento11 páginasTunica Vaginalis Flap Reinforcement in Staged Hypospadias RepairDrMadhu AdusumilliAinda não há avaliações

- Obturatorhernia PDFDocumento4 páginasObturatorhernia PDFAmanda Samurti PertiwiAinda não há avaliações

- Fifteen Years Experience in Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair in Pediatric Patients. Results and Considerations On A Debated ProcedureDocumento5 páginasFifteen Years Experience in Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair in Pediatric Patients. Results and Considerations On A Debated ProcedureRagabi RezaAinda não há avaliações

- Anal Abscess and FistulaDocumento12 páginasAnal Abscess and FistulaGustavoZapataAinda não há avaliações

- 05 CastelnuovoDocumento7 páginas05 Castelnuovogabriele1977Ainda não há avaliações

- Nasopalatine Duct CystDocumento4 páginasNasopalatine Duct CystVikneswaran Vîçký100% (1)

- Cirugías de La Glándula Mamaria en El BovinoDocumento20 páginasCirugías de La Glándula Mamaria en El BovinoJavier HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Incisional Hernia Mesh RepairDocumento5 páginasIncisional Hernia Mesh Repaireka henny suryaniAinda não há avaliações

- How I Do ItDocumento13 páginasHow I Do ItvennyherlenapsAinda não há avaliações

- Peritonsillar Abscess DrainageDocumento4 páginasPeritonsillar Abscess Drainagesyibz100% (1)

- Ismaeil 2018Documento15 páginasIsmaeil 2018Javier ZaquinaulaAinda não há avaliações

- Submental Flap Reconstruction for Oral Cavity CancerDocumento3 páginasSubmental Flap Reconstruction for Oral Cavity CancerKaran HarshavardhanAinda não há avaliações

- Translabprevention CSFJCGPRLDocumento5 páginasTranslabprevention CSFJCGPRLJohn GoddardAinda não há avaliações

- Nasopalatine Duct Cyst-Manuscript Case Report Haji - MIODocumento6 páginasNasopalatine Duct Cyst-Manuscript Case Report Haji - MIOdrg.montessoAinda não há avaliações

- Bilateral Nasolabial Cyst MarcoviceanuDocumento4 páginasBilateral Nasolabial Cyst MarcoviceanubamsusiloAinda não há avaliações

- Urushihara 10.1007 s00383-015-3779-8Documento4 páginasUrushihara 10.1007 s00383-015-3779-8CherAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal tht7Documento5 páginasJurnal tht7Tri RominiAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Patologi AnatomiDocumento5 páginasJurnal Patologi Anatomiafiqzakieilhami11Ainda não há avaliações

- Referat Pleomorphic AdenomaDocumento6 páginasReferat Pleomorphic AdenomaAsrie Sukawatie PutrieAinda não há avaliações

- Wound: Abdominal DehiscenceDocumento5 páginasWound: Abdominal DehiscencesmileyginaaAinda não há avaliações

- 2016 Classification of ParotidectomiesDocumento6 páginas2016 Classification of ParotidectomiesAzaria SariAinda não há avaliações

- Umbilical Vascular Catheterization: Videos in Clinical MedicineDocumento3 páginasUmbilical Vascular Catheterization: Videos in Clinical MedicineStephanie RomeroAinda não há avaliações

- Cutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseDocumento6 páginasCutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseRhian BrimbleAinda não há avaliações

- Original Article: Tympanic Epidermosis: A Noncholesteatomatous Keratinizing Entity of Chronic Otitis MediaDocumento7 páginasOriginal Article: Tympanic Epidermosis: A Noncholesteatomatous Keratinizing Entity of Chronic Otitis MediaGunalan KrishnanAinda não há avaliações

- Abcess PeritonsillarDocumento21 páginasAbcess PeritonsillarribeetleAinda não há avaliações

- Short Nose Correction-By Man Koon SuhDocumento4 páginasShort Nose Correction-By Man Koon SuhJW整形医院(JW plastic surgery)Ainda não há avaliações

- 234 FarmerDocumento6 páginas234 FarmerRaghavendra NalatawadAinda não há avaliações

- Original Research Article: Amitkumar Rathi, Vinod Gite, Sameer Bhargava, Neeraj ShettyDocumento8 páginasOriginal Research Article: Amitkumar Rathi, Vinod Gite, Sameer Bhargava, Neeraj ShettyAkanshaAinda não há avaliações

- Adenoma 2020Documento11 páginasAdenoma 2020Residentes AudiologiaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceNo EverandCase Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceAinda não há avaliações

- Living and radiological anatomy of the head and neck for dental studentsNo EverandLiving and radiological anatomy of the head and neck for dental studentsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Retromolar Canal Infiltration Reduces Pain of Mandibular Molar RCTDocumento6 páginasRetromolar Canal Infiltration Reduces Pain of Mandibular Molar RCTSetu KatyalAinda não há avaliações

- Plan Vouchers 12092019Documento2 páginasPlan Vouchers 12092019sevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Profession Tax Procedure OnlineDocumento1 páginaProfession Tax Procedure Onlinehemanvshah892Ainda não há avaliações

- Antibiotics in Oral & Maxillofacial SurgeryDocumento50 páginasAntibiotics in Oral & Maxillofacial SurgerysevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Preprosthetic SurgeryDocumento27 páginasBasic Preprosthetic SurgerysevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Praveena Clinic Visiting CardDocumento1 páginaPraveena Clinic Visiting CardsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Closed Reduction Nasal Fracture Post Op InstructionsDocumento2 páginasClosed Reduction Nasal Fracture Post Op InstructionssevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Best Practices OMFS DEPTDocumento2 páginasBest Practices OMFS DEPTsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Penjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisDocumento28 páginasPenjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisWitri Septia NingrumAinda não há avaliações

- Sterilization of ArmamentariumDocumento41 páginasSterilization of ArmamentariumsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- SBV Dissertation Template 2017Documento22 páginasSBV Dissertation Template 2017sevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Nerve InjuriesDocumento39 páginasNerve InjuriessevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Lesions in Neonates PDFDocumento8 páginasOral Lesions in Neonates PDFsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Life and Work of Shri Hans Ji MaharajDocumento75 páginasLife and Work of Shri Hans Ji Maharajsevattapillai100% (1)

- Sterilization and AsepsisDocumento48 páginasSterilization and AsepsissevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Post-Extraction Complication Course PDFDocumento11 páginasPost-Extraction Complication Course PDFsevattapillai100% (1)

- DNA Probes and Primers in Dental PracticeDocumento6 páginasDNA Probes and Primers in Dental PracticesevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Life of Gajanan Vijay Granthi UneditedDocumento63 páginasLife of Gajanan Vijay Granthi UneditedsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Congenital Ranula in A Newborn A Rare PresentationDocumento3 páginasCongenital Ranula in A Newborn A Rare PresentationsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Lymphangioma of The Tongue PDFDocumento3 páginasLymphangioma of The Tongue PDFsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Oral LymphangiomaDocumento8 páginasOral LymphangiomasevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Jackie ChanDocumento1 páginaJackie ChansevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Lymphangioma of The TongueDocumento3 páginasLymphangioma of The TonguesevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- The Effects of Using Hyaluronic Acid On The Extraction SocketsDocumento5 páginasThe Effects of Using Hyaluronic Acid On The Extraction SocketssevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Congenital Sublingual CystDocumento5 páginasCongenital Sublingual CystsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Periapical Lesions - A Review of Clinical, Radiographic, and Histopathologic Features PDFDocumento7 páginasPeriapical Lesions - A Review of Clinical, Radiographic, and Histopathologic Features PDFsevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Lesions in NeonatesDocumento8 páginasOral Lesions in NeonatessevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- Nonsurgical Management of Periapical LesionsDocumento11 páginasNonsurgical Management of Periapical LesionssevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- A Retrospective Study On The Use of A Dental Dressing To Reduce Dry Socket Incidence in SmokersDocumento5 páginasA Retrospective Study On The Use of A Dental Dressing To Reduce Dry Socket Incidence in SmokerssevattapillaiAinda não há avaliações

- CANINE Impaction Oral SurgeryDocumento46 páginasCANINE Impaction Oral SurgeryFourthMolar.com100% (5)

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion NCPDocumento5 páginasIneffective Tissue Perfusion NCPJasmin Calata50% (2)

- QuestionsDocumento19 páginasQuestionsFatma AlbakoushAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation OB - GYNDocumento14 páginasCase Presentation OB - GYNRaidah Ayesha RazackAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Cases On Art. 12Documento3 páginasSample Cases On Art. 12mmaAinda não há avaliações

- PMLS 1 Topic 8.0 TransDocumento6 páginasPMLS 1 Topic 8.0 TranslalaAinda não há avaliações

- Complementary and supplementary feeding essentialsDocumento23 páginasComplementary and supplementary feeding essentialsArchana100% (1)

- Physiology Previous Year PDFDocumento129 páginasPhysiology Previous Year PDFmina mounirAinda não há avaliações

- April 28 FibrinolysisDocumento7 páginasApril 28 FibrinolysisCzarina Mae IlaganAinda não há avaliações

- Unit I Introduction To HealthDocumento11 páginasUnit I Introduction To Healthishir babu sharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Manzolli Etal 2015Documento8 páginasManzolli Etal 2015gustavormbarcelosAinda não há avaliações

- BPPVDocumento2 páginasBPPVGavin TexeirraAinda não há avaliações

- OBDocumento7 páginasOBWilmaBongotanPadawilAinda não há avaliações

- NARAYANA Hrudayala - TariffDocumento82 páginasNARAYANA Hrudayala - TariffRama VenugopalAinda não há avaliações

- Synchronization and Artificial Insemination Strategies in Beef CattleDocumento13 páginasSynchronization and Artificial Insemination Strategies in Beef CattleCARLOS ANDRES MARQUEZ SANCHEZAinda não há avaliações

- Lung Ultrasound For Neonatal Cardio-Respiratory Conditions: Daniele de Luca (MD, PHD)Documento52 páginasLung Ultrasound For Neonatal Cardio-Respiratory Conditions: Daniele de Luca (MD, PHD)Claudia Kosztelnik100% (1)

- References: Plant Profile, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Argemone Mexicana Linn.A ReviewDocumento1 páginaReferences: Plant Profile, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Argemone Mexicana Linn.A ReviewSachin DatkhileAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnostic Imaging of Exotic Pets Birds, Small Mammals, Reptiles - oDocumento468 páginasDiagnostic Imaging of Exotic Pets Birds, Small Mammals, Reptiles - oAna Inés Erias67% (6)

- Elmhurst Teacher's Council's Filing With The Illinois Educational Labor Relations BoardDocumento27 páginasElmhurst Teacher's Council's Filing With The Illinois Educational Labor Relations BoardDavid GiulianiAinda não há avaliações

- Covid-19 Virus RT-PCR (Truenat) Qualitative: DLCLPBDDocumento1 páginaCovid-19 Virus RT-PCR (Truenat) Qualitative: DLCLPBDAdnan RaisAinda não há avaliações

- Rabies National Guideline of ID PET Final Jun2010 ZipDocumento34 páginasRabies National Guideline of ID PET Final Jun2010 ZipFazle Rabbi ChowdhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Cast, Brace, Traction CompilationDocumento13 páginasCast, Brace, Traction CompilationMar Ordanza100% (1)

- Adhd and Children Who Are GiftedDocumento3 páginasAdhd and Children Who Are GiftedCyndi WhitmoreAinda não há avaliações

- Guillain Barre SyndromeDocumento8 páginasGuillain Barre SyndromeStephanie AureliaAinda não há avaliações

- Kumpulan Soal Bhs - InggrisDocumento6 páginasKumpulan Soal Bhs - Inggrismaria friska nainggolanAinda não há avaliações

- SUBJECT VERB AGREEMENT LET ReviewerDocumento2 páginasSUBJECT VERB AGREEMENT LET ReviewerMacky ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- 899 PDFDocumento3 páginas899 PDFManuel CarboAinda não há avaliações

- Amphetamine Drug Fact Sheet: Uses, Effects, Legal StatusDocumento1 páginaAmphetamine Drug Fact Sheet: Uses, Effects, Legal StatusEvandro Ricardo GomesAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomical Zodiacal Degrees PDFDocumento6 páginasAnatomical Zodiacal Degrees PDFMaria Marissa100% (2)

- Papilloma Skuamosa: Laporan Kasus Dan Tinjauan PustakaDocumento4 páginasPapilloma Skuamosa: Laporan Kasus Dan Tinjauan PustakarizkyayuarristaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 MSN UNIT 1introductionDocumento57 páginas1 MSN UNIT 1introductionVikash PrajapatiAinda não há avaliações